IT WAS 11:00 P.M. IN WASHINGTON, D.C. Daniel Ellsberg’s first day at the Pentagon was now his first night.

Ellsberg and other staff members were gathered with John McNaughton in his office, reading the latest cables and waiting for the president’s announcement. A big TV screen flickered, the volume turned down.

At 11:37, they saw President Johnson’s face on the television. Someone turned up the sound.

“My fellow Americans,” Johnson began, speaking from a podium in the White House. “As President and Commander-in-Chief, it is my duty to the American people to report that renewed hostile actions against United States ships on the high seas in the Gulf of Tonkin have today required me to order the military forces of the United States to take action in reply.”

Johnson told viewers that the North Vietnamese attacks had been fought off, with no American casualties. “But repeated acts of violence against the Armed Forces of the United States must be met not only with alert defense, but with positive reply,” he said. “That reply is being given as I speak to you tonight.”

He made clear that the strikes would be limited. For months, Johnson had been assuring Americans that he had no intention of expanding the country’s role in Vietnam. As he had put it often, “We seek no wider war.”

Now he repeated the pledge. “We Americans know, although others appear to forget, the risks of spreading conflict. We still seek no wider war.”

* * *

The early afternoon skies were blue above the coast of North Vietnam. Alvarez had a clear view of the rocky coast, dotted with islands.

“When we go in, everybody drop back,” Commander Bob Nottingham radioed to the other Skyhawk pilots. “Alvie and I’ll go in first.”

Nottingham began his approach, with Alvarez flying wing just seventy feet back. Diving at five hundred miles per hour, they saw the docks, and tied up there, as the briefers had told them, were four torpedo boats and one bigger patrol ship.

Alvarez fired his rockets as he sped past the target, then began banking to come around again.

“Look out!” another pilot shouted to Alvarez over the radio. “They’re shooting at you!”

Alvarez saw black clusters of antiaircraft flak bursting all around his plane. He flipped the switch to arm his 20 mm gun.

“I’m going in again,” he told the team.

All ten Skyhawks had taken shots at the targets, and the torpedo boats were on fire. Alvarez sped over the pier again, strafing the bigger ship from barely a hundred feet above the water.

Then he heard a sudden BOOM and saw a yellow flash over his left wing.

“The plane shook violently,” he later said, “rattling and clanking as if someone had thrown a bucket of nuts and bolts into the engine.” All the warning lights in the cockpit came on. Smoke started pouring in.

“I’ve been hit!” Alvarez shouted over his radio. “I’m on fire and out of control!”

The plane swerved to the left and started falling from the sky.

“I’m getting out! I’ll see you guys later!”

Alvarez felt for the ring hanging behind his head and pulled. The plane’s canopy shot off and a rocket blasted his seat into the air, the sudden rush of wind nearly knocking him unconscious. He heard the POP of his parachute opening. Seconds later he hit the water.

Ripping off his helmet, Alvarez could see that he was a few hundred yards from the coast. Bobbing in the water nearby were several fishing boats, manned by Vietnamese militiamen with rifles. They were moving toward him.

Alvarez thought of his wife. They’d been married just seven months. He took off his wedding ring and let it sink.

* * *

Daniel Ellsberg spent the night at the Pentagon monitoring the air strikes. A total of sixty-four American planes hit four North Vietnamese patrol boat bases. Early in the morning on August 5, he went home to his empty apartment.

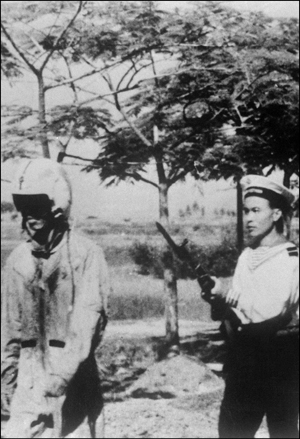

August 1964. U.S. Navy pilot Everett Alvarez is taken prisoner by a North Vietnamese sailor after being shot down.

President Johnson flew to upstate New York that morning to dedicate a new building at Syracuse University. After a brief mention of the building, he turned to the action in Vietnam, emphasizing that the air strikes had been made necessary by the North Vietnamese torpedo boat attacks.

“The attacks were deliberate,” Johnson said. “The attacks were unprovoked. The attacks have been answered.”

Back in Washington, D.C., later that day, the president focused on next steps. Priority number one was to gain congressional approval for expanded military action in Vietnam, if deemed necessary. Johnson and his aides quickly finalized the language of what became known as the Tonkin Gulf Resolution. Here’s the key sentence:

“Congress approves and supports the determination of the President, as Commander-in-Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”

Essentially, the resolution was designed to grant the president the power to order further attacks in Vietnam without asking Congress for a formal declaration of war. Johnson submitted it to Congress. House and Senate leaders agreed to hold hearings the next day.

* * *

Late that night, Wayne Morse, a senator from Oregon, got a call from a man he knew in the Pentagon. The caller told Morse he wanted to pass on some information, but only on the strictest assurance that the source would never be revealed. Morse agreed.

The secretive caller informed Morse that whatever attacks had taken place on the American destroyers had hardly been, as the president claimed, “unprovoked.” Part of the reason the Maddox was in the Gulf of Tonkin was to support the recent South Vietnamese raids on the North. American forces, the caller explained, were heavily involved in planning and carrying out those raids. The caller urged Morse to question Secretary McNamara about this.

The next morning, on Capitol Hill, Senator Morse cornered several senators before the joint hearings of the Senate Armed Services and Foreign Relations Committees began. He was hoping to convince colleagues to join him in asking McNamara some tough questions.

“Hell, Wayne,” one told him, “you can’t get in a fight with the president at a time when the flags are waving.”

The hearings were closed to the public. McNamara urged quick passage of the resolution. The senators seemed supportive—with the exception of Wayne Morse.

“I am unalterably opposed to this course of action which, in my judgment, is an aggressive course of action on the part of the United States,” Morse said.

He didn’t know about the doubts surrounding the August 4 “attacks” on Americans ships—and McNamara certainly didn’t volunteer that information. But Morse definitely suspected that whatever had happened in the Gulf, the Americans were hardly innocent bystanders.

McNamara categorically denied this.

“Our Navy played absolutely no part in, was not associated with, was not aware of any South Vietnamese actions, if there were any,” he told the senators. “I want to make that very clear to you.” The Maddox had been on a routine patrol, he insisted, no different from patrols carried out by American ships every day, all over the world. “I think it is extremely important that you understand this,” he lectured. “If there is any misunderstanding on that we should discuss the point at some length.”

“I think we should,” Morse answered.

“I say this flatly,” McNamara shot back. “This is the fact.”

McNamara was blatantly misleading Congress, but aside from Morse, no other senators knew it. Some had misgivings about handing President Johnson what was practically a declaration of war, especially in such a hurry, and with such a vague idea of where things might lead. Still, most saw it as their responsibility to rally around the president.

“Our national honor is at stake,” said Senator Richard Russell of Georgia. “We cannot and we will not shrink from defending it.”

The committees voted 31–1 in favor of the resolution, with only Morse opposing. The full Senate vote was 88–2. The House approved the Tonkin Gulf Resolution 416–0.

* * *

President Johnson’s approval rating shot up fourteen percentage points. Eighty-five percent of the public supported Johnson’s handling of the crisis. Reelection in November looked certain.

Daniel Ellsberg’s reaction was different. Unlike most Americans, he was seeing things from the inside.

He already had serious doubts that American ships had been attacked in the Gulf of Tonkin on the stormy night of August 4. Over the following hours and days, reading classified cables in his Pentagon office, Ellsberg learned the truth about the South Vietnamese attacks on North Vietnam. McNamara had told Congress the United States had “played absolutely no part in” these raids. In fact, they had been top secret operations planned by the CIA. The U.S. Navy provided the Swift boats, machine guns, and training.

“They were entirely U.S. operations,” Ellsberg concluded. “Every particular detail of these operations was known and approved by the highest authorities in Washington.”

President Johnson and Secretary of Defense McNamara were telling the world that the American destroyers had been on a routine patrol in the Gulf of Tonkin. They declared the ships had definitely been attacked on August 4. They insisted the attacks had been unprovoked.

“Within a day or two,” Ellsberg would later say, “I knew that each one of these assurances was false.”

But what was he supposed to do with that kind of information?

* * *

What he did not do was walk away from his new job.

Ellsberg was new to Washington, but he was not naïve. He knew the government did not really function like the neat little charts in some middle-school civics textbook. Yes, Johnson and McNamara were telling Congress and the public only part of the story of recent events in Vietnam. But secrecy was an essential element of military operations, and Ellsberg was not one to blow the whistle. “I really looked down on people who had done that,” he said of insiders who leaked secrets. “You shouldn’t play the game that way.”

In his final analysis, only one point truly mattered—this was the Cold War. Ellsberg’s job was to help win it. “We were all cold warriors,” he explained. “We couldn’t conceive of any alternative to what we were doing.”