Buckey O’Neill was one of Arizona’s most colorful characters. The swashbuckling Irishman was a newspaperman, politician, mayor of Prescott and sheriff of Yavapai County. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

1

BUCKEY O’NEILL AND THE TRAIN ROBBERS

Arizona attracted a number of flamboyant characters during its territorial years, but none was more colorful than William O. “Buckey” O’Neill. His good looks and witty charm made him a darling of the ladies, and his gallant charisma made him a natural leader of men. He made his reputation as a newspaperman, judge, politician, lawman, soldier and go-for-it gambler. His nickname came from “bucking the tiger,” or betting against the house in the popular game of faro on Prescott’s famed Whiskey Row.

He stood nearly six feet tall with a stylish mustache; dark, handsome looks; and a devil-may-care persona that attracted legions of admirers. Gregarious, witty and self-confident, he could quote Lord Byron at the drop of a hat and was fearless in the face of danger.

Buckey was born in Ireland and was only nineteen years old when he rode into Phoenix in 1879. Seeking adventure, he soon headed for Tombstone during the heyday of Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday and Johnny Ringo but returned to Phoenix three years later to become a deputy city marshal under the famed Henry Garfias. His next stop was Prescott, where in 1888 he got into politics and was elected sheriff of Yavapai County.

On a cold March day in 1889, not long after Buckey had taken the oath of office, four Hash Knife cowboys—Bill Sterin, John Halford, Dan Harvick and J.J. Smith—decided to up their station in life by robbing the Atlantic and Pacific Eastbound No. 2 passenger train. They planned to pull the heist while it was stopped to replenish its wood box at Canyon Diablo, twenty-four miles west of Winslow.

The train robbers came out of the dark shadows of the section house, poked their six-guns in the faces of the crew and forced open the express safe, taking some $7,000 in cash, pocket watches and a set of diamond earrings. They then rode off into the night in a snowstorm. The plan was to ride south a few miles to deceive the posse and then turn north and head for Utah.

Buckey O’Neill was one of Arizona’s most colorful characters. The swashbuckling Irishman was a newspaperman, politician, mayor of Prescott and sheriff of Yavapai County. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

About five miles south of Canyon Diablo, they stopped to divide up the loot. Among the booty was a pair of diamond earrings. Smith pried the diamonds loose from their settings and dropped them into his pocket, where he proceeded to forget about them. Later, he unwittingly scraped some tobacco crumbs and the diamonds out of his pocket and put them in his pipe. Afterward, he knocked the ashes out on his boot heel, and with them went the diamonds.

Canyon Diablo was in Yavapai County back in those days before Coconino County was created and was about the same size as the entire state of New York. Buckey had been in office only three months, and this would be his first real test as a lawman.

O’Neill and his deputy, Jim Black, were already in Flagstaff when the robbery occurred. They were soon joined by special deputy Ed St. Clair of Flagstaff and two railroad detectives, Carl Holton and Fred Fornoff.

They picked up the outlaws’ trail in the high desert north of Flagstaff and followed it until they met a Navajo woman who told them four men had run off that morning with a mutton she’d just skinned. Buckey sent a young Navajo boy to Winslow to ask the telegrapher to send messages to the villages in southern Utah to be on the lookout.

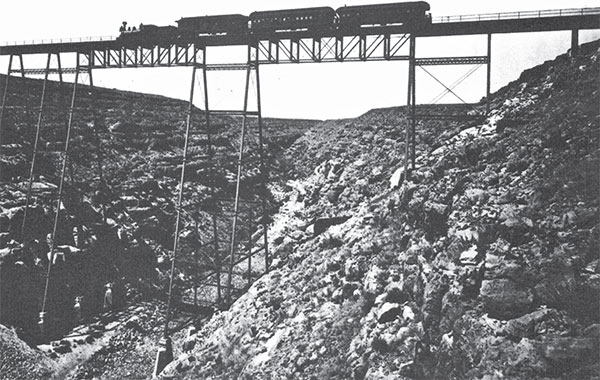

A Santa Fe passenger train rolls over the Canyon Diablo during the 1880s. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

Meanwhile in Utah, the four outlaws arrived at the small Mormon community of Cannonville, located in a valley just east of Bryce Canyon. Word had reached residents to be on the lookout for the four desperadoes, and not long after, they came riding boldly into town.

The Mormons treated them with reserved kindness, fed them and offered them a place to sleep. The four hard-looking strangers cautiously accepted the hospitality and settled in for the night. While the trail-weary train robbers were sleeping, the local constable, along with a posse of farmers, got the drop on them, but J.J. Smith was able to turn the tables. He nabbed the town patriarch, who then ordered the citizens to throw down their guns. The marauders took their weapons, stole some supplies and rode out of town firing indignant shots into the air.

When the posse arrived at Lee’s Ferry, they learned the outlaws had crossed two days earlier, headed north for Wahweep Canyon at today’s Lake Powell and then turned south back toward Lee’s Ferry, and that’s where the posse caught up with them. They came upon a deserted camp, but fresh tracks and warm ashes from a campfire meant the train robbers weren’t far away. The train robbers’ tracks led into a box canyon. They had unwittingly gotten themselves literally boxed in. Surrounded on three sides by precipitous cliffs and a posse in front, the four men spurred their mounts and charged toward the lawmen with guns blazing. Buckey’s horse was shot out from under him in the first round of fire, pinning him beneath.

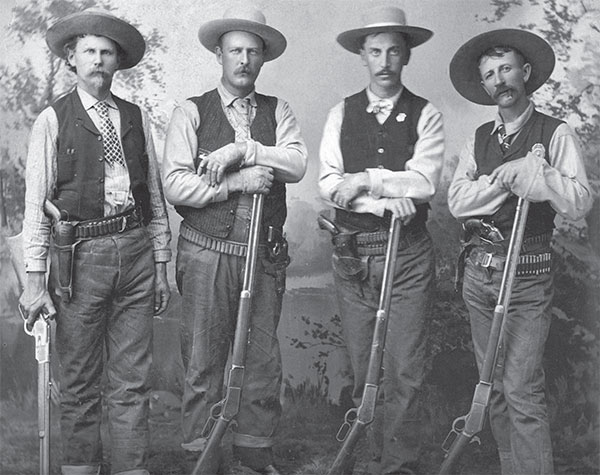

The Canyon Diablo posse. Left to right: Carl Holton, Ed St. Clair, Buckey O’Neill and Jim Black. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

The posse men quickly dismounted and pried Buckey from under his horse. He slid his Winchester from the scabbard and continued to return fire, the bullets ricocheting off the canyon walls and peppering the outlaws with sandstone.

The gunfire had frightened the outlaws’ horses, causing them to stampede into the brush and leaving the gang afoot. Halford and Sterin were captured first. Smith and Harvick made a run for it, leaping over a bluff and bouncing down to the canyon floor.

The pair was able to dodge the lawmen the rest of that day and through the night, crawling through brush and over rocky crevasses. Finally, footsore, thirsty and tired, they arrived at a small watering hole, where they bathed their swollen feet in the cool water. They were getting ready to leave when a shot crashed nearby, showering them with pieces of rock. Afoot, weary and dispirited, the last two outlaws threw down their guns and surrendered.

By the time one of the Old West’s greatest pursuits was over, Buckey and his posse had been in the saddle three weeks and had ridden over six hundred miles.

At Panguitch, Utah, the local blacksmith put leg irons on the bandits. Then they took the long way back to Prescott by way of Salt Lake City and Denver and then headed home on the Santa Fe Railroad.

On the way, J.J. Smith managed to slip out of his shackles and jump off the train, but the other three arrived in tow.

Buckey was hailed as a hero by the territorial governor and the citizens, but when he submitted his travel expenses, all out of pocket, the county board of supervisors refused to pay the whole amount, saying that by chasing the outlaws into Utah, he’d gone out of his jurisdiction. Buckey sued them and won.

Buckey O’Neill would go on to even greater glory. He was mayor of Prescott in 1898 when war broke out with Spain. Arizonans eagerly volunteered to join the First United States Volunteer Cavalry, a brainchild of the colorful Teddy Roosevelt. They became better known as the Rough Riders and would become the most celebrated unit in the war.

Buckey was selected as captain of Company A, made up mostly of men from northern Arizona. The Rough Riders were a mixed bag of rogues, short on discipline and long on energy, but in no time at all they became a crack fighting outfit, and Buckey O’Neill was their most popular officer. His noble sense of justice made him a favorite of the enlisted men. The handsome Irishman became the personification of the beau ideal Rough Rider.

The Arizona Rough Riders fought in the two major battles of the war in Cuba: Las Guasimas and the San Juan Heights. In both fights, Buckey stood defiantly in front of the lines as if he was challenging the Spanish snipers to shoot him. More than once he declared, “The Spanish bullet is not molded that will kill me.”

Captain O’Neill had the luck of the Irish with him right up to the end. He staunchly believed an officer should always stand and face the enemy. Despite pleading from his troops, he refused to take cover in a trench.

Buckey continued walking up and down the line shouting encouragement to his troopers. Around ten o’clock on the morning of July 1, 1898, a random shot from a Spanish sniper ended the life of Buckey O’Neill. The men of Company A stared in shocked disbelief at the sight of their leader lying dead on the battlefield. He would be the only officer in the Rough Riders to die in battle.

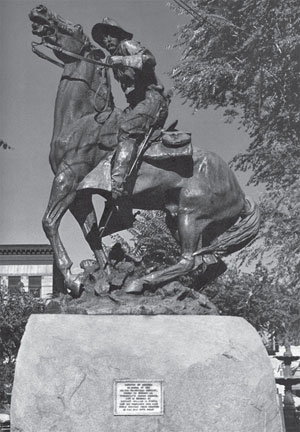

The Rough Rider , sculpted by Solon Borglum, was dedicated in Prescott on July 3, 1907. It’s been called one of the world’s best equestrian statues. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

At the courthouse plaza on July 1, 1907, a statue honoring the Rough Riders was dedicated in the plaza in downtown Prescott. Today, it’s more familiarly known as the “Buckey O’Neill Statue” in honor of one of Arizona’s greatest heroes. Created by the noted sculptor Solon Broglum, many regard it as one of the finest equestrian statues in the world.

Among the lawmen of the Old West, the colorful Irishman was one of the most brave and daring. His incredible feats made him a legend in his own lifetime. He died as he’d lived.

A few years earlier, in an article titled “A Horse of the Hash Knife Brand,” he’d written:

The Indians were right. Death was the black horse that came some day [sic] into everyman’s camp, and no matter when that day came a brave man should be booted and spurred and ready to ride him out .