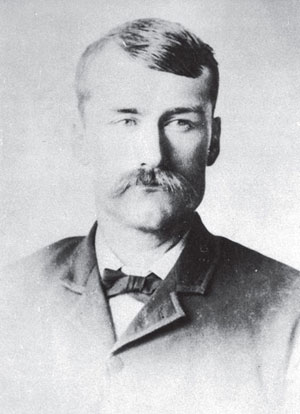

Jim Roberts was top gun for the Tewksbury faction in the Pleasant Valley War. After the feud subsided, he became a deputy sheriff in Yavapai and Cochise Counties. Courtesy Southwest Studies Archives .

2

JIM ROBERTS

THE PLEASANT VALLEY WAR’S TOP GUN

Sometime around eleven o’clock on the morning of June 21, 1928, Earl Nelson and Will Forrester drove into the smelter town of Clarkdale and parked on the main street outside the Bank of Arizona. The two men, bank robbers from Oklahoma, got out of the car and walked into the bank lobby. Nelson, the younger of the two, was carrying a parcel wrapped in a newspaper. He paused and waited by the door.

The gunmen had been living in Clarkdale a few weeks and had been casing the bank for the heist. They figured the best time to pull the job was around midday and at a time when the big Phelps Dodge payroll was in the vault. They also planned their escape carefully. In the car was a box of nails to toss into the road in case they were being pursued. They also had cayenne pepper and oil of peppermint to befuddle hound dogs if they had to abandon the car and head into the wild country on foot.

Clarkdale was a quiet company town, and a bank robbery in broad daylight was highly out of the ordinary. And that’s what the outlaws were counting on. Inside the bank, a few customers were standing in front of the grilled windows of the tellers’ cages. Others were filling out deposit or withdrawal slips at the counter.

Will Forrester walked past the customers and headed for the manager’s office located next to the cages. When he was in a position to cover the room, he whipped out a pistol and shouted to bank employees Bob Southard, Marion Marston and Margaret Connor, “Step back here and no foolishness. The bank is being robbed.”

Earl Nelson stepped from the lobby and pulled the newspaper wrapping from a sawed-off shotgun. “Just don’t move, folks, and everything will be all right,” he said grinning, “We won’t keep you long.”

While the customers looked on in shock, Forrester pulled a gunnysack from beneath his coat and gave it to the teller at the same time, motioning with his pistol for the employees to start filling it with money.

About that time, David Saunders, bank manager, returning from a trip to the post office, walked in to find his bank being robbed. Saunders was ordered to move over with the others. While Forrester turned his attention to the money stashed in the open vault, he slowly moved toward his desk. The robber saw Saunders’s movement out of the corner of his eye and swung his pistol menacingly toward the manager, saying, “You turn in an alarm and I’ll come back and kill you if it takes twenty years.”

The gunnysack was stuffed with cash, some $40,000. Forrester ordered the employees and customers into the vault, where they would be locked away while the two made their escape.

As the vault door was being closed, bank manager Saunders protested they would all suffocate in the vault he claimed was airtight. A mass murder would be added to their charge of bank robbery. Forrester reluctantly decided to lock them behind the outside grating door only. Before leaving, he issued a stern warning that anyone stepping outside the bank would be shot.

Once the robbers left the bank, Saunders began working on the grating lock. Within moments, he had the door open. He grabbed a gun from beneath a teller’s window and rushed into the street, firing into the air.

Jim Roberts was top gun for the Tewksbury faction in the Pleasant Valley War. After the feud subsided, he became a deputy sheriff in Yavapai and Cochise Counties. Courtesy Southwest Studies Archives .

By this time, the two bandits were in their car and driving off. They had just rounded a corner about one hundred feet down the street. With all their careful planning, they hadn’t reckoned on an old gunfighter from the days of yore happening on the scene.

Jim Roberts, a Yavapai County deputy sheriff and town constable, was making his rounds when he heard the commotion. By some curious twist of fate, he’d reversed his rounds that morning and just happened to be in the right place at the right time. Roberts was seventy years old and approaching the end of a long and illustrious career as a lawman and gunfighter.

Jim Roberts also was something of a disappointment to the hero-worshiping youngsters of 1920s Clarkdale. They’d learned all about the Old West watching Saturday afternoon matinees at the movie theater. They’d seen Tom Mix leap mighty canyons on his wonder horse, Tony. They knew real gunfighters like Mix, Buck Jones and Hoot Gibson packed two pistols in buscadero gun belts and wore fancy high-heeled boots, silver spurs, wide-brimmed hats and bright-colored, silk neckerchiefs.

One day, an adult explained to the kids that the old lawman had been a famous gunfighter in his day and was the best gunman in the Pleasant Valley War. Still, the youngsters were skeptical. “Uncle Jim,” as they called the old-timer, wore eastern clothes and packed his pistol in his back pocket. He neither smoked, drank nor played cards, and the strongest cuss word he could muster was “dang.” To add to their disillusionment, he preferred to ride a white mule instead of a long-legged stallion. He was friendly if you said hello, but start asking him questions about his illustrious past and he’d clam up tighter ’en a cigar-store wooden Indian. Like the rest of the feudists who really took part in the notorious Graham-Tewksbury Feud, Roberts was tight-lipped. Writers were coming around trying to get a scoop, and the only ones talking were those who didn’t really play a major part or know what they were talking about. Men like Roberts knew that by talking, old wounds would fester and hard feelings would return. It was better to leave it lie. Silence was a characteristic common to feudists throughout the West.

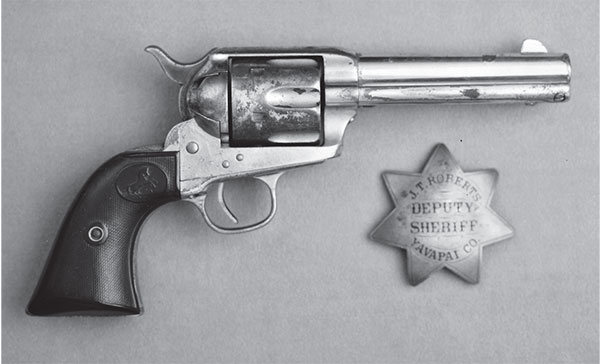

Old-timers tell a story in Verde Valley about the time a movie company offered Roberts a substantial sum of money to be technical director of a film on the Pleasant Valley War. He stunned them by refusing to divulge what he knew. As a consolation, they asked if he would show them all how the old gunfighters drew and fired their six-guns. He obliged by reaching into his hip pocket and pulling out his nickel-plated Colt and, using both hands, took a slow, deliberate aim. Expecting to see a lightning-fast draw, the movie people were disappointed. The youngsters, used to Tom Mix and the other shooting stars of Hollywood, were convinced he was a phony.

But what happened in the next few moments in Clarkdale would make true believers of a whole new generation. Uncle Jim was still a force to be reckoned with.

The old lawman saw a car gathering speed as it roared past him. His instincts told him the men in the automobile were up to no good. Then he saw the gun pointing at him.

From inside the speeding car, Nelson saw the old man with a badge pinned on his shirt and opened fire.

These two “eastern” bank robbers had no way of knowing the old man staring at them was the legendary Jim Roberts, one of the greatest gunfighters to ever pin on a badge. He certainly didn’t look like a gunfighter. His eyes squinted as if he needed glasses. He was wearing a black eastern-style hat, and he wasn’t wearing a gun belt.

The old lawman, ignoring the screaming bullets, drew a nickel-plated Colt .45 from his hip pocket and, holding the revolver with two hands, drew a bead on the driver of the speeding car. The pistol roared and bucked as flame shot from the muzzle. Forrester’s head jerked backward as a bullet struck him. Another shot rang out, striking a tire. In an instant, the car skidded and then careened off the road and into the schoolyard, where it smashed into the guy wire of a telephone pole.

Will Forrester was dead at the wheel with a bullet wound in the neck. Nelson, his clothes bloodied from his partner’s gunshot wound, jumped from the crash and ran into the schoolhouse. He momentarily considered making a stand but surrendered meekly when he saw the old lawman coming through the door with smoking six-gun in hand.

Earl Nelson was arraigned in Clarkdale before being turned over to Yavapai County sheriff George Ruffner and taken to Prescott. Inside the getaway car were two shotguns, two pistols, a rifle and a coil and fuse for setting off dynamite, as well as the keg of nails and cayenne powder. Nelson was only twenty-three but had a long criminal record in Oklahoma, where he’d been a member of an outlaw gang. For a time, Arizona lawmen kept him well guarded, fearing gang members from Oklahoma would try to spring him. He was eventually sentenced to thirty to forty years in the state penitentiary at Florence. In 1931, he escaped by hiding in the false bottom of a dump truck. He was later caught hiding out in Phoenix. One story has it he pulled another bank robbery and stashed the loot, some $40,000, hiding it somewhere near Stoneman Lake. Another story has it he boasted to inmates at the state prison in Florence that he and Forrester had robbed a bank in Oklahoma and buried the money around the lake. Whichever version one chooses to believe, treasure hunters have searched in vain for the bandit’s stash. It’s still the subject of a Dean Cook song and several lost-treasure stories.

Old Jim Roberts was a whole lot more than those young whippersnappers bargained for. Men had underestimated him before. He was extremely tight-lipped about his past. One man had ridden with Roberts for years and never knew he’d been a key figure in the Pleasant Valley War until a writer told him. Jim had never mentioned it.

Back in the early 1970s, as a young historian, I had the pleasure of becoming acquainted with Roberts’s son, Bill. Off and on for several weeks, he regaled me with stories about his father, but he had no luck trying to get him to talk about the Pleasant Valley War. He recalled that when the famous lawman came home for lunch after thwarting the Clarkdale bank robbery, his mother asked why he was later than usual, and he casually replied, “There was some trouble downtown.” That was all he ever said about the gunfight.

Long before thwarting what was at the time the biggest heist in Arizona history, Jim Roberts had carved a niche for himself in the lore of great gunfighters and lawmen. He was considered the top gun in the Pleasant Valley War. He wasn’t like some of those young hellions who rode into the valley looking to start “a little war of our own”; Roberts was a quiet man who settled there to raise horses. He was reluctantly drawn into the conflict when some of the Graham faction stole his horses and burned his cabin.

Jim Roberts was born in Bevier, Macon County, Missouri, in 1858. He arrived in Arizona when he was eighteen. Little is known about the early years of his life. His son, Bill, once told the author that his mother only knew that he was “from Missouri.” During the mid-1880s, he arrived in Pleasant Valley and settled near the headwaters of Tonto Creek at the foot of the Mogollon Rim. One day, a team of horses turned up missing, and Roberts tracked them to a camp of Graham supporters. He inquired if anyone had seen his horses, and the boys made some flippant remarks about their whereabouts, which confirmed his suspicions. As Roberts started to ride away, one of them remarked, “That’s a damn fine horse he is riding, and when he stops tonight we’ll get him too.”

Another version—and there are as many versions of this feud as there are storytellers—had Roberts tracking down three horse thieves and killing them all in a shootout. Jim Roberts was what was known in the Old West as a “man with bark on.”

They never got his horse, but they had incurred the wrath of the man who would prove to be the most deadly gunman among the Tewksbury faction. How many men he personally accounted for in the war is open to conjecture. Roberts didn’t discuss those matters, even with members of his family.

Jim Roberts had been friendly with the Tewksbury boys since moving into Pleasant Valley, and after the horse-thieving incident, he joined the clan in the war with the Grahams.

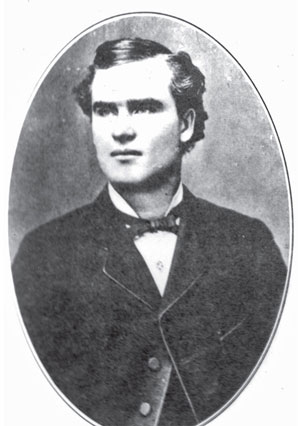

Ed Tewksbury, an expert rifleman, was the leader of his faction in the famous Graham-Tewksbury Pleasant Valley War. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

The Graham-Tewksbury war had its beginnings around 1880, when Jim Stinson moved a large herd of cattle into remote Pleasant Valley. The valley was nestled beneath the Mogollon Rim, 75 miles northeast of Globe and a three-day trip by wagon. The railroad town of Holbrook was 100 miles north of the valley. The county seat at Prescott was 150 miles to the west over rough terrain. Both Payson and Flagstaff were small settlements at the time.

James Dunning Tewksbury and his family moved from California into the valley in 1879. His Hupa/Hoopa Indian wife and the mother of his boys, John, Ed, Jim and Frank, had died in California. In late 1879, the senior Tewksbury married a widow named Lydia Schultes of Globe. Despite having grown children from previous marriages, J.D. and Lydia had two more children of their own, becoming one of those “his, hers and ours” families. One of Lydia’s daughters, Mary Ann, married J.D.’s oldest son, John. The Tewksburys settled on ranches on the east side of Cherry Creek.

Tom Graham, leader of the Graham gang. Don’t let his calm, preacher-like appearance fool you. He was a deadly killer. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

The Graham brothers, Tom, John and Billy, arrived in the valley from Ohio in 1882, ironically at the invitation of Ed Tewksbury. The two families got along well at first. They settled on the west side of the Cherry Creek. In the annals of the West, most feudists waged war from ranches located at least several miles apart. The Graham-Tewksbury war was unusual in that the ranches were within eyesight of each other.

Jim Stinson branded his cattle with a simple “T,” an invitation to alter if there ever was one. Soon there were a dozen or so brands stamped on cows’ hides that were all various alterations of the “T,” including the famous “Hash Knife” up on the Mogollon Rim.

In January 1883, John Gilliland, foreman for Stinson, rode over to the Tewksbury ranch and accused them of stealing his boss’s cattle. Tom and John Graham were visiting the Tewksburys at the time. Gilliland was accompanied by his fifteen-year-old nephew, Elisha, and a vaquero named “Potash” Ruiz.

Ed Tewksbury stepped out and said, “Good morning, boys, who are you looking for?”

Gilliland jerked his six-gun and replied, “You, you son of a bitch.” His shot missed. Tewksbury grabbed a .22 rifle and returned the fire, hitting both Gilliland and Elisha. The youngster fell to the ground as Gilliland and Potash rode away. Both wounds were minor, however, in July, Gilliland filed murder charges against the Tewksburys.

The Tewksburys were ordered to ride 150 miles to Prescott to answer charges. A judge dismissed the case as frivolous, but on the ride home, a weakened Frank Tewksbury took sick and died. The enraged Tewksbury brothers blamed Frank’s death on Stinson and Gilliland.

It’s believed that sometime during the trial, Stinson cut a deal with the Grahams in which they would secretly work for him as range detectives, for a price. This classic double-cross would certainly be cause for the Tewksburys to transfer their vengeful feelings to the Grahams and their friends.

On March 29, 1884, John Graham did in fact file a felony complaint against the Tewksbury brothers for altering brands on sixty-two head of cattle. At the trial in Prescott, the defendants were all found innocent, and perjury charges were leveled against the Grahams.

Was cattle rustling the root of the feud? Probably. A lot of ranches got their start with a long rope and a running iron, and Stinson’s cattle were easy pickings. It’s been claimed the feud started over sheep being driven off the rim onto the cattle ranges, but that came later. It’s also been claimed the feud started over a woman, but that seems unlikely.

During the next eighteen months, the tension mounted. The Tewksburys were running short of money defending themselves from trumped-up charges, and Stinson was losing both cattle and money trying to protect his interests. As far as the Tewksburys were concerned, Stinson was using his power and money to run them out of business.

On July 22, 1884, John Tewksbury and George Blaine rode into the Stinson ranch and, after a heated exchange, engaged in a brief gunfight. Both suffered wounds at the hands of Stinson’s men. After a brief inquiry, no charges were pressed, and the matter was officially dropped.

At some point during that time, John Tewksbury had whipped John Graham in a fistfight. Things were certainly heating up.

Mart Blevins and his family arrived from Texas around 1886. He and his sons—John, Charley and Hamp Blevins and Sam Houston—took over a ranch mob-style on Canyon Creek and hooked up with the Graham faction. Another of Mart’s boys, Andy Blevins, using the alias Andy Cooper, had arrived from Texas two years earlier. He’d already gained a reputation as a badman in Texas. Anticipating action, more ruffians descended on the valley.

More fuel was thrown on the fire in February 1887, when Bill Jacobs, a friend of the Tewksburys, drove a flock of sheep into Pleasant Valley. It didn’t take cattlemen long to retaliate. A sheepherder was killed, his body riddled with bullets and, according to some accounts, beheaded.

In July, Mart Blevins rode off from the Canyon Creek ranch on the trail of some horse thieves and was never seen again. A few days later, Hamp Blevins, along with four Hash Knife cowboys—John Paine, Tom Tucker, Bob Carrington and Bob Glaspie—were out searching for Hamp’s father. They met cowhand Will C. Barnes at Dry Lake, about thirty miles south of Holbrook, and mentioned they were headed for Pleasant Valley to “start a little war of our own.”

On the ninth of August, they arrived at the Newton (old Middleton) Ranch, located on Wilson Creek at the eastern part of Pleasant Valley. The ranch was the scene of a battle with Apaches a few years earlier and had been abandoned by the Middleton family and was now occupied by George Wilson. Inside, Jim Roberts, Joe Boyer and Jim and Ed Tewksbury were sitting down to dinner when the riders approached. The boys, still sitting on their horses, asked to be invited in for a meal.

“We aren’t keeping a boarding house,” Jim Tewksbury told them, “especially for the likes of you.”

John Paine had a reputation as a bad hombre with a real mean streak who loved to fight. He’d been hired by a big outfit to beat up on small ranchers and shipmen in the area and enjoyed it. Tom Tucker was mostly looking for adventure. Glaspie was more stupid than mean and was easily led by killers like Paine. Not much is known about Bob Carrington.

Hamp Blevins drew his pistol and started firing, drawing a fusillade of fire from inside the cabin. The first volley of gunfire, Jim Roberts dropped Paine with a shot between the eyes. Another shot tore off the top of Blevins’s head. Both toppled to the ground with fatal wounds. Then Tucker went down with a bullet in the chest. Bob Glaspie took a bullet in the right leg. Carrington’s clothes were perforated, but he managed to escape unhit. None of the Tewksburys were hurt. It’s likely the Tewksburys and Roberts were using the latest rapid-firing Winchester Model 1886 .45-90 rifles. As one old-timer put it, “It was like shooting a cannon.”

Tucker, badly wounded, managed to ride away but later fell from his saddle. Along the way, he was attacked by a mama bear and her two cubs. By the time he reached a ranch, the chest wound was covered with maggots, and that probably saved his life, as maggots eat only dead flesh, thus preventing gangrene from setting in.

Glaspie was wounded in the leg, the bullet passing through the cantle of his saddle and exiting through his buttocks. During the fight, his horse was also shot out from under him. He managed to make his way on foot back to the Blevins ranch on Canyon Creek three days later.

The nefarious little war party off to start a little war of their own was fully routed.

Immediately following the battle, the defenders inside the cabin saw another large party approaching. They quickly made ready for another siege. When the riders were close enough, Roberts saw they were Apache, armed and painted for war. But when they saw the carnage, one of them shouted “chinde,” an Apache word for ghosts. Fearing the presence of evil, or the deadly aim of the shooters inside, they quickly turned tail and rode off.

Jim Roberts and the Tewksburys decided not to press their luck any further, and they, too, rode off.

That evening, members of the Graham faction returned to bury the bodies and before leaving burned the cabin to the ground.

The Tewksbury cabin in Pleasant Valley. Note the bullet holes in the walls. Courtesy Southwest Studies Archives .

Following the shootout, John Blevins had some second thoughts about security at the ranch on Canyon Creek. The ranch had been a lair for horse thieves, but with the killing of his brother Hamp and mysterious disappearance of his father, Mart Blevins, he decided to relocate the family to a little cottage in Holbrook until things cooled off a bit. Ironically, it was less than a month later that Apache County sheriff Commodore Perry Owens went to the house to arrest one of the Blevinses. In the ensuing gun battle, two more Blevins brothers would die, and John would be seriously wounded.

On September 2, 1887, Jim Roberts, along with several members of the Tewksbury family, were at the Lower Tewksbury Ranch on Cherry Creek (both the Tewksburys and Grahams had three ranches in the valley) when some twenty Graham partisans, led by Andy Cooper Blevins, attacked the ranch. Among them were Tom and John Graham, Mote Roberts (not related to Jim) and Charlie and John Blevins. Some accounts claim future governor George W.P. Hunt was among the gang.

Historians disagree on who was inside the solid-walled cabin that day. One version has it Ed Tewksbury and John Rhodes were there, while J.D. was in Prescott. Another says J.D. and Lydia were in Phoenix. Still another has Ed and Jim with Jim Roberts at their “mountain hideaway,” eluding warrants for their arrests, while John Rhodes was at the Tewksbury headquarters.

Others inside the cabin included John Tewksbury’s pregnant wife, Mary Ann; J.D.’s wife, Lydia; her twelve-year-old son; and their two youngsters, ages three and six.

The Graham partisans positioned themselves on the opposite side of Cherry Creek in the brush and waited. After breakfast John Tewksbury and Bill Jacobs headed out to wrangle the horses. Several shots rang out, and the two men fell to the ground, shot from behind. One of the shooters walked up to Tewksbury, fired three more shots into him and then picked up a huge rock and smashed his head.

The attackers kept firing into the cabin throughout the day. They paused long enough to announce that John Tewksbury and Jacobs were dead, but they wouldn’t allow the Tewksbury men to see them. Apparently they did allow Lydia, her young son and possibly Mary Ann to look at the bodies.

Mary Ann Tewksbury would later claim she begged Tom Graham to let her bury her husband and Jacobs, but he refused.

Apparently the Graham partisans believed the Tewksburys had gunned down Old Man Blevins and then allowed the wild hogs to eat him, for Tom Graham replied, “No, the hogs have got to eat them.”

It was claimed that Andy Cooper Blevins wanted to scalp Tewksbury, but Tom Graham forbade it. Graham knew if one side started taking scalps, the other would respond in kind.

Cooper also wanted to burn the cabin but, because of the women and children inside, was again forbidden by the others.

During the fight, John Rhodes slipped away, evading the snipers, and headed to the mountain hideaway to alert Jim Roberts, Joe Boyer and Jim Tewksbury. Roberts then rode hard to Payson to summon Justice John Meadows and a posse.

Rhodes, Tewksbury and Boyer rushed back to the siege but were driven back by withering rifle fire from the Graham partisans. They managed to gain a position atop a nearby hill, where they could return fire and support Ed, who was firing from inside the cabin.

Help didn’t arrive for eleven days. Snipers hung around for several days, firing at anyone who tried to leave the cabin. The men foraged for wood and brought in water at night.

Some versions say Mary Ann defied the snipers, who peppered her feet with rifle shots during the day, by creeping out at night and, since the ground was too rocky to dig graves, covering the bodies with bed sheets anchored with rocks to keep the hogs from devouring the bodies.

By the time the posse arrived, the snipers had left, and what was left of the bodies of the two slain men was placed in an Arbuckle Coffee crate and buried in a single grave.

Mary Ann gave birth to her baby boy ten days after the fight and named him John after her late husband. She later married John Rhodes, and the boy, who took his stepfather’s last name, became a rodeo cowboy, winning World Champion Roper in 1936 and 1938.

The Tewksburys were understandably bitter. Later, Jim Tewksbury would say contemptuously, “No damned man can kill a brother of mine and stand guard over him for the hogs to eat him and live within a mile and a half of me.”

Two weeks after the bushwhacking of John Tewksbury and Bill Jacobs, the Grahams staged another daring ambush on Jim and Ed Tewksbury, the remaining brothers, and Jim Roberts while they were camped at Rock Springs on Canyon Creek. On the morning of August 17, Graham partisans crept up before dawn and positioned themselves to attack on horseback at first light. They were expecting to catch the Tewksburys and Roberts sleeping, but it was not to be. Roberts had gotten up early and gone out to gather the horses. He saw the Grahams approaching and rushed back to warn the others, who grabbed their rifles and opened fire. All of them crack shots, Roberts and the Tewksburys poured deadly accurate fire, emptying the saddles of several Graham partisans. Harry Middleton took a bullet and died a few days later at the Graham ranch. Joe Ellingwood was sniping away from behind a tree, his leg exposed. Roberts drew a bead on the leg and put a bullet through his calf. Another unwisely made a taunting gesture by rubbing his butt. A shot rang out, and the man “jumped ten feet” with a bullet in the rump.

After a while, Tom Graham called for a truce to remove the dead and wounded. Unlike the previous battle at the Middleton cabin, where Graham partisans kept the Tewksbury faction pinned down for eleven days while semi-wild hogs feasted on the bodies of John Tewksbury and Bill Jacobs, the Tewksburys graciously allowed the Grahams to bury their dead and carry off their wounded. The Tewksburys and Roberts watched soberly as the Grahams tossed the bodies of the dead into a crevasse and threw rocks and dirt on top. The dead were transient gunmen hired by Tom Graham, and their names remain unknown. Perhaps Graham didn’t even know their names.

The Pleasant Valley War was making national news by now, and lawmen from the county seat at Prescott were moving through the area trying to arrest members of both factions. Yavapai sheriff Billy Mulvenon and his posse of some twenty men rode toward Young again.

The sheriff was still smarting from an earlier visit. While he and his men were meeting with Graham partisans to arrange a truce between the opposing parties, someone stole all their horses. This time the sheriff meant business. The Perkins Store in Young was about a mile south of the Graham ranch. Mulvenon posted his men behind the four-foot-high rock wall at the store and dispatched riders to circle around the valley to attract attention. Signal shots were fired from the Graham house and by a partisan, Al Rose. Strangers in the valley were always cause for curiosity, and Charley Blevins and John Graham rode cautiously down toward the store to check out the strangers. When they were near enough to see the danger, they spurred their horses and headed toward an arroyo north of the store. Lawmen opened fire and emptied their saddles. They also arrested two others, Al Rose and Miguel Apodaca. Rose talked tough, saying, “If you want anything here come and get it.” But when he saw the number of guns pointed at him, he meekly surrendered. Tom Graham, the leader, was able to escape the posses of both Sheriff Mulvenon and Commodore Perry Owens and made his way to Phoenix.

Following those arrests, the posse rode into the lair of the Tewksburys. Their surrender had been prearranged; the Tewksburys and Roberts had said they’d come in peaceably once the Grahams were corralled, and they did. Later, when it was learned Tom Graham had gotten away, the Tewksburys were livid.

The fighting men from both sides were taken to Payson to appear before Justice of the Peace John Meadows, and all were released for lack of evidence except Roberts, Joe Boyer and the Tewksbury brothers. They were held over for a grand jury in Prescott for the shootings at the Newton ranch. Bond was posted, and they all returned to Pleasant Valley and tried to pick up the pieces of their lives. Although Jim Roberts was indicted for murder in the range war, prosecutors eventually dropped all charges.

Al Rose would later be hanged by vigilantes.

The price in blood had been heavy for both sides, especially for the Blevins, Graham and Tewksbury families. John Blevins, wounded at Holbrook, was the sole survivor of the fighting men in his family. His father, Mart, along with brothers Andy, Hamp, Charley and Sam were all killed during the feuding. Tom Graham was the sole survivor of his family, losing his two brothers, Billy and John.

Ed was the last of the fighting Tewksburys. Frank died of pneumonia in 1883. In a weakened condition, he’d been forced to ride 150 miles in bad weather to Prescott to answer some trumped-up charges by the Grahams. On the way home he got sick and died. John was killed during the war, and Jim would die of consumption in December 1888.

The “war proper,” as they called it, was over; however, assassinations and lynchings would continue for quite some time.

It’s been said fifty-four people disappeared and twenty-eight were known killed in the feud. The vigilance committee, calling itself the “Committee of Fifty,” actually numbered far fewer. Silas Young and Colonel Jesse Ellison were the leaders of this phantom group. They spoke of restoring order, but there’s hard evidence the self-righteous pair saw an opportunity for a land grab. Young and Ellison each wanted it all but eventually agreed to a split. Silas Young took over the Graham ranch, and Ellison claimed the Tewksbury ranchlands on the east side of the creek.

In the aftermath, Tom Graham got married and settled down in Tempe. But feuds and bad blood don’t die easy. On Tuesday morning, August 2, 1892, he was driving a wagonload of grain on Double Buttes Road leading into town. Beside the road, Ed Tewksbury and his brother-in-law John Rhodes sat waiting in ambush. As the wagon passed, Tewksbury raised his weapon, a .45-90 Winchester rifle, and shot Graham in the back. He slumped back on the sacks of grain, mortally wounded. He lived long enough to name his assassins. Tewksbury made a hasty escape by picketing a relay of fast, durable horses from Tempe to the Tonto Basin. To establish his alibi, Ed Tewksbury had to ride 170 miles in less than a day.

Ed Tewksbury, proclaiming his innocence, surrendered. Fearing a lynching, lawman Henry Garfias met Ed at the Kyrene railroad station and they rode quietly into Phoenix, where he was booked in the county jail.

Ed Tewksbury continued to deny any involvement, claiming he was in the Tonto Basin at the time. Actually, he’d picketed some fine horses along the way and made a record-setting endurance ride to establish his alibi.

John Rhodes was tried first, and his trial turned out to be quite a sensation. Anne Melton Graham, Tom’s widow, slipped a pistol into the courtroom in her purse and attempted to shoot Rhodes, but the weapon failed to fire.

Rhodes had an alibi—he claimed to be somewhere else, and the court believed him. He later became an Arizona Ranger.

Ed Tewksbury’s lawyers used delaying tactics to postpone his trial for some sixteen months after the murder of Tom Graham. His alibi of being in the Tonto Basin the day of the shooting was doused when a witness testified to seeing Ed drinking in a Tempe saloon that same day.

Then his lawyers got a change of venue and moved the trial to Tucson. The argument came down to whether or not Tewksbury could have ridden from Pleasant Valley to Tempe and back in a day.

The jury returned a guilty verdict, but Ed’s lawyers went on the offense, arguing, on legal technicalities, that Ed hadn’t appeared in person for his plea of abatement, and he was given a new trial.

Richard E. Sloan, future territorial governor of Arizona, was the judge at the new trial. This time, Ed’s lawyers planted a seed of doubt in the eyes of the jury, and the result was a hung jury. After two and a half years behind bars, Ed was free on bond. By now, too much time had passed, and the prosecution, believing it could not get a conviction, dismissed all charges. Ed Tewksbury was a free man. He sold his holdings in Pleasant Valley and moved to Globe, where he became a well-respected deputy sheriff. He died in 1904 of consumption. Ed Tewksbury would be the inspiration for Zane Grey’s classic novel of the feud, To the Last Man .

In reality, Jim Roberts was the last man.

Jim Roberts’s days as a warrior in the Graham-Tewksbury Feud were over. For the next forty-four years, he would wear a badge and keep the peace. And there was no better lawman in Arizona when it came to taming tough towns. In 1889, the new Yavapai County sheriff, Buckey O’Neill, appointed him deputy and assigned him to the mining town of Congress in the southern part of the county. Romance came into the life of the handsome lawman at Congress. There he met Permelia Kirkland, pretty daughter of the renowned rancher-pioneer William Kirkland. At the time, Kirkland was justice of the peace at Congress.

Kirkland was a man of many firsts in Arizona. He’d been the first Euro-American to engage in ranching in Arizona; he raised the first American flag over Arizona following the Gadsden Purchase; he and his wife, Missouri Ann, were the first Euro-American couple to marry in Arizona; and they were the parents of the first Euro-American child born in Arizona. His third child, Ella, born in 1871, was the first Euro-American child born in Phoenix.

Jim Roberts met the lovely Melia Kirkland at a dance in Congress. She was the belle of the town, and he asked her to dance. Afterward, he gave her a piece of candy. Although the pretty twenty-year-old blond was engaged to someone else at the time, Roberts came courting two days later. She later said of her intended, “He was a nice boy, but Jim was a real man.” On November 17, 1891, they were married in Prescott. They would eventually have a family of three sons and two daughters.

Following the wedding, he and Melia moved to the rough-and-ready town of Jerome. Jim had proven to be a capable lawman, and the new sheriff, Jim Lowery, figured him up to the task to tame the mining camp on the slopes of Cleopatra Hill.

Payday came only once a month, but it was Katy-bar-the-door. Saloons, gambling halls and bordellos were open twenty-four hours a day to accommodate the lusty miners. It was said the shutters on the buildings were extra thick to keep the inside shootings in and the outside shootings out. The local jail wasn’t large enough to hold all the arrests, so Roberts handcuffed prisoners to wagon wheels, hitching posts and anything else that was strong enough to hold them.

Jerome had its share of desperados. One time Roberts went after an outlaw on his mule, Jack. He preferred the sure-footed animals on the dangerous mountain slopes. The man had boasted he wouldn’t be taken alive, so the lawman led a little burro to haul the corpse back. Sure enough, that’s how they returned.

One old-timer from Jerome told of his own baptism of fire while working as a young deputy with Roberts. Three men had gotten into a fight in a gambling hall and had committed a murder. They holed up on the outskirts of town and challenged Roberts to come and get them. As the lawmen approached the three killers, Roberts said quietly to the young deputy, “You take the one in the middle, and I’ll get the front one and the other one.”

He glanced at the youngster out of the corner of his eye and saw his gun hand was shaking badly. “Never mind, son,” he said kindly, “I’ll take ’em all.” And he proceeded to gun down all three.

“Jim never did say much,” said one old-timer, “and when he was mad, he said nothing at all.”

One of his best-known pursuits and capture of desperadoes came when Sid Chew and Dud Crocker murdered his deputy Joe Hawkins.

It began one evening in a vacant lot down the street from the Fashion Saloon. Crocker was handcuffed to a wagon wheel. He’d started a fight in a saloon earlier and been pistol-whipped into submission by Hawkins. The sullen Crocker determined to get even by killing the deputy when he got loose.

After dark, when things quieted down, his partner Sid Chew crept up, took a wrench from the toolbox on the wagon and removed the axel nut from the wagon wheel. Chew pulled the wheel from the spindle, and the two picked up the wheel and hauled it down the street to the blacksmith shop. The streets were quiet; most of the noise was coming from the saloons. No one noticed as Chew pried open the swinging doors with a pinch bar. He lit a coal oil lantern and heard a voice from the rear of the shop where the blacksmith’s helper bunked. “Who’s there?” he asked.

“Come give us a hand,” Chew called back.

When the helper walked in, Chew hit him with a roundhouse punch to the jaw. The helper stumbled backward, fell and split his head open on an anvil.

Chew hurriedly picked up a chisel and hammer and cut the handcuffs from the wheel. In a moment, Crocker was free of his bonds. They doused the lantern and headed back to the little room at a boardinghouse they shared. Each man armed himself with a pistol.

A few minutes later, a commotion down the street told them Crocker’s escape had been discovered. Deputy Hawkins knew where Crocker lived, and he wasted no time getting to the boardinghouse. As he approached, they opened fire, hitting the deputy several times. Before going down, Hawkins got off a shot, hitting Chew in the leg.

The rampage of Chew and Crocker that evening had taken two lives.

By the time Jim Roberts had been summoned, the two killers had taken two horses at gunpoint from a livery stable and ridden into the night.

Roberts climbed on his trusty mule and, leading a pack burro, headed down the mountain toward the Verde River. His years in the Pleasant Valley War had taught him all the finer points of tracking, and his experience as a lawman had taught him how to think like a fugitive. He figured correctly the two would get into the river to cover their trail and head downstream toward Camp Verde. He also figured they’d hole up during daylight near a hill where they could look back to see if they were being followed.

The lawman rode into Camp Verde and learned that no riders had passed that way, so he headed back up the river until he came to a commanding hill. He climbed to the top, being careful to keep some chaparral between him and the river. Sure enough, when he got to the top he could see a wisp of smoke coming from a thick monte by the river.

He slipped quietly down to the river and crept up to where he could see two men shivering beside a small campfire.

He called out to the men, “No need shootin’. Just drop your guns. Don’t draw.”

The two murderers jumped away from the fire, grabbed their six-guns and fired in the direction of the voice. Roberts’s first shot dropped Crocker with a bullet to the head. Chew charged, firing wildly. Roberts’s next shot drove him backward to the ground.

The Colt revolver and Yavapai County badge worn by Jim Roberts. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

Later that day, the quiet lawman rode into Jerome with the bodies of Chew and Crocker tied across his pack animal and delivered them to the undertaker.

On December 8, 1892, he was elected constable of the Jerome district and served that office for the next eleven years. In April 1904, he was elected town marshal of Jerome.

Tragedy struck the Roberts family in 1902, when three of their four children died during an epidemic of scarlet fever in Jerome. First to die was five-year-old Jim Jr., who died less than forty-eight hours after coming down with the fever. Three days later, Nellie died. Two weeks later, they lost nine-month-old Myrtle. His wife, Melia, and nine-year-old Hugh both contracted the disease but recovered. A fifth child, Bill, was born after the epidemic.

Jim Roberts was a devoted family man and was deeply hurt by the loss of his children. A quiet man by nature, it was said he became even more withdrawn after burying his children. A story is told he’d promised to buy little Nellie a rocking chair, but she died before he could, so after the funeral, he brought home a small rocker in remembrance.

Leaving Jerome, he took a job as deputy sheriff in Cochise County. During the next few years, he worked as a peace officer in Florence and Humboldt.

The tragic death of his children in Jerome had left such a painful memory that he vowed never to return to the mining town nestled on the slopes of Cleopatra Hill. But time helped heal the wounds, and in 1927, at age sixty-nine, he took the job as special officer for the United Verde Copper Company with a deputy’s commission from Yavapai County and was stationed at Clarkdale.

True to his nature, after the gunfight with Nelson and Forrester, the old lawman finished his rounds and headed home for lunch. His wife later recalled how she was concerned because he was late, and the biscuits had gotten cold. He apologized, saying “he’d had a little trouble downtown” and quietly finished his meal without saying anything more about the gunfight.

Jim Roberts died while making his rounds on the evening of January 8, 1934. He suffered a heart attack and collapsed. Somebody found him and called an ambulance, and Uncle Jim died on the way to the hospital—with his shoes on. That was another thing: Jim Roberts didn’t wear boots.