One of the Old West’s most famous gunfights occurred in Holbrook in 1887 between Apache County sheriff Commodore Perry Owens and members of the Blevins family. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

4

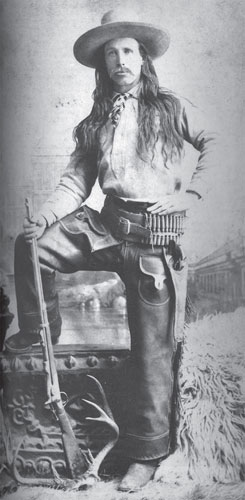

COMMODORE PERRY OWENS

BRINGING LAW AND ORDER TO APACHE COUNTY

When old-time shooters, sitting around Gunfighter Valhalla, that mythical hall into which the souls of warriors are received, get to reminiscing about the great gunfighters of the Old West, Apache County sheriff Commodore Perry Owens is certain to be mentioned. Although Owens isn’t exactly a household name in the West, and the roaring cow town of Holbrook, where he made his mark, isn’t as well known as Tombstone, Dodge City or Abilene, Owens’s spectacular shootout with members of the Blevins family is unsurpassed in the annals of the Old West.

Apache County historian Jo Baeza wrote:

From the beginnings of language to the present, there have been certain prerequisites to becoming a folk hero. They have little to do with morals, as mores change from epoch to epoch, people to people. More important in folklore are the timeless virtues of courage, honesty, physical strength, skill with a weapon and a conflict that the hero single-handedly resolves. Remember all these things as you read about Commodore Perry Owens .

Commodore Perry Owens was born on July 29, 1852, on a small farm in eastern Tennessee. Contrary to popular belief, he was not born on the anniversary of Oliver Hazzard Perry’s great naval victory over the British on September 10, 1813, at the Battle of Lake Erie. His father was named Oliver H. Perry Owens in Commodore Perry’s honor, and his mother gave him the name.

Owens drifted down to Texas in the early 1870s and then on to Indian Territory, where he took a job on the Hilliard Rogers ranch near today’s Bartlesville. Over the next few years, he worked as a cowhand driving cattle from Texas to the cow towns of Kansas. He also worked as a buffalo hunter for the Atlantic and Pacific in Kansas, honing his skills as an expert shot.

He arrived in Holbrook in 1881, about the same time as the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. Soon after his arrival, he took a job guarding the stage station at Navajo Springs from horse thieves who preyed on the area. He had several brushes with local Navajos over disputed stock, and it was said they came to view him as an invisible ghost because their bullets never seemed to hit, while his “magic” guns never missed. Owens’s experience as a buffalo hunter on the Kansas plains had turned him into an expert marksman.

Owens homesteaded at the Z Bar ranch some ten miles south of the springs where he raised purebred horses. The place became known as Commodore Springs.

Owens was described as a simple, charismatic man of few words, and when he did speak, it was with a slow drawl. He was a handsome man, standing five feet, ten inches, with light blue eyes and a slight, sinewy frame. According to old-timers, he cut a romantic swath on his fine sorrel horse with the pretty ladies around Concho and St. Johns.

Owens also had a reputation for integrity. One newspaper was quoted as reporting, “Mr. Owens is a quiet, unassuming man, strictly honorable and upright in his dealings with all men and is immensely popular.” He took few men into his confidence and had few intimate friends.

One of the Old West’s most famous gunfights occurred in Holbrook in 1887 between Apache County sheriff Commodore Perry Owens and members of the Blevins family. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

An early acquaintance described him as “kind and courteous, but very quiet, a perfect gentleman.” Another said he was the most superstitious man he’d ever known. A man of action, not given to introspection, he was extremely cool under pressure—the type oft described as a “good man to ride the river with.”

A cowhand named Dick Grigsby told a story that Owens was making biscuits one morning inside his two-room shack when two Navajo horse thieves began firing rounds into his abode from opposite directions. Owens calmly picked up his rifle, walked to the door, shot both raiders and waited quietly for a few minutes before proceeding to finish cooking his biscuits.

At the time of Owens’s arrival in Apache County, there were serious problems of civil strife and lawlessness. Among the causes were issues along ethnic and religious lines as a number of groups competed for political and economic power. Mexicans, Mormons, non-Mormons and Navajos all jockeyed for position in the Little Colorado River Valley. Cattlemen competed with sheep men for grazing rights. Texans and Mexicans harbored deep resentment toward each other, dating back to the Battle of the Alamo. There was also contention between the Mormons and Mexicans in St. Johns. The Navajo troubles were mostly over rustling, along with conflicting claims to water and grazing rights. And lastly, the Aztec Land and Cattle Company was trying to rid the country of nesters. Maintaining law and order in Apache County was not a job for the meek.

Holbrook, located at the junction of the Rio Puerco and Little Colorado and straddling the new Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, was soon to become one of the wildest cow towns in the West.

Before the railroad arrived in 1881, Holbrook was known as Horsehead Crossing. The community was renamed Holbrook in 1882 for H.R. Holbrook, who was the first engineer on the Santa Fe (Atlantic and Pacific) Railroad. By 1887, the town had about 250 residents. Businesses included a Chinese restaurant run by a man named Louey Ghuey, Nathan Barth’s store, Schuster’s store and five or six saloons. Contrary to popular myth, there never was a “Bucket of Blood” saloon. That was a humorous nickname given by the cowboys to any rough-and-tumble drinking establishment.

The social elite of the town included the wide gamut of colorful frontier types: filles de joie , gamblers, sheepherders, cowboys and railroaders.

Holbrook in those days was, in the immortal words of Mark Twain, “no place for a Presbyterian,” so very few remained Presbyterians, or any other religion for that matter. In fact, the town had the unique distinction of being the only county seat in the United States that had no church until 1913. And that only came after Mrs. Sidney Sapp cajoled her attorney husband into organizing a fund to build one.

Apache County, in those days, was a vast, rugged area of some 20,940 square miles, larger than Vermont and New Hampshire combined. Originally a part of Yavapai County, it was created in 1879.

The arrival of the railroad in 1881 opened up the plateau country of northern Arizona to large-scale cattle ranching. The territory’s most spectacular ranching enterprise, the Aztec Land and Cattle Company, better known by its Hash Knife brand, was running some sixty thousand cows and two thousand horses on two million acres of private and government land. The absentee-owned outfit was literally surrounded by rustlers, who preyed on the herd like a pack of wolves. Many of the rustlers were not outlaws by trade but small ranchers who felt they had a right to rustle Hash Knife stock because the big outfit had taken over public lands.

To expedite the building of transcontinental railroads, the federal government awarded railroads like the Atlantic and Pacific alternate checkerboard sections on both sides of the tracks. The railroads, in turn, sold the land to private corporations. The even-numbered ones remained government property. Thus, if an outfit like the Aztec bought one million acres, its cattle could actually graze on twice that amount.

The nesters figured that if the big outfits could graze their cattle for free on public lands, then they should have a right to harvest a few of those cows.

It was estimated that one and a half million cows occupied the ranges of Arizona. All those cows naturally attracted the lawless element, and soon the ranges were overrun with horse thieves and rustlers. One report claimed fifty-two thousand cows were rustled in one year alone. Convictions for outlawry were rare; the Hash Knife went fourteen years without getting a single conviction for rustling.

The situation had become so desperate that, in the fall of 1887, the Apache County Stock Association hired a range detective to eliminate a few of the most rapacious outlaws in hopes of putting the others to flight. Only two men in the organization knew the identity of the regulator, and they were sworn to secrecy. The association used its entire savings, some $3,000, for bounty money and used its political persuasion to have the hired gun appointed a United States deputy marshal. The gunman, acting as judge, jury and executioner, moved with swift vengeance. Cold and calculating, he shot down two well-known rustlers who “resisted arrest.” He then read warrants over their dead bodies. The six-gun justice served up by a mysterious avenging angel was enough to strike terror in the hearts of the rabble and sent many of them scurrying for other pastures. This mysterious range detective’s identity was kept a secret, but it’s believed it was Jonas V. “Rawhide Jake” Brighton, a former bad man who became a hired gun for law and order.

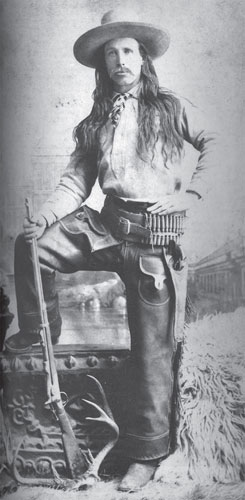

Cowboys bellied up to the bar in Winslow. Note the lack of feminine company. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

By 1886, Owens was working as a deputy sheriff in Apache County. There were some who would later claim that Commodore Perry Owens was also brought in by the association as a hired gun. True or not, he did much to cut down on the population of cow thieves in Apache County. Hailed by the St. Johns Herald as the “people’s candidate,” he was elected sheriff on November 4, defeating incumbent John Lorenzo Hubbell of trading-post fame.

Newspapers rejoiced at the election of Owens, proclaiming he would bring an end to the lawlessness in the county. There was quite a celebration following Owens’s victory. In Holbrook, revelers were firing their pistols in the air. George Lee got so caught up in the excitement he accidentally shot his finger off.

Owens received strong support from both the Mexicans and the Mormons, and it was likely their votes that ensured his election. The previous administration had been anti-Mormon and had slandered them on matters concerning religious beliefs. Both groups believed he was their protector at a time when everyone was persecuting them to get their land and water rights. Also both groups believed Owens was the man to bring law and order to that part of the territory.

Up to that time, Owens hadn’t done anything to cause so much public adulation, but he brought honesty and integrity to the office, and that was certainly a refreshing change in Apache County politics. He was also known as a dead shot with both rifle and pistol. He often entertained locals with shooting exhibitions.

Owens’s honesty was quickly demonstrated in the way he handled the expenses of the sheriff’s office, right down to costs incurred for postage stamps. He cleaned up the county jail, which he described in a report as in a “horribly, filthy condition,” and installed rules to restrict problems in the jail.

Two gangs of outlaws in particular were singled out for the new sheriff’s immediate attention: the Clanton gang, late of Tombstone, and the Blevins boys, recent arrivals from Texas.

By the time Owens took office, the citizens of Apache County were demanding that both gangs be brought to justice. The St. Johns Herald hinted that if the law didn’t do its job, the citizens would resort to lynch law.

Ike and Fin Clanton, who had survived the Cochise County War against Wyatt Earp and his brothers five years earlier, had moved their operations to the Springerville area. Their ranch, the Cienega Amarilla, was located east of Springerville, near Escudilla Mountain. The Clantons had been accused of terrorizing local citizens, cattle rustling, train robbery and holding up the Apache County treasurer. Under the leadership of family patriarch Newman Haynes “Old Man” Clanton, they had created a successful business in Cochise County during the late 1870s and early 1880s brokering stolen livestock from Mexico. The old man was killed in an ambush at Guadalupe Canyon in the summer of 1881, and the youngest, Billy, died a few weeks later in the so-called Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

A story was told around Tombstone that the Clantons often boasted the reason they were so successful in the cattle business was that they didn’t have to buy their cows.

Ike was a fairly likeable figure around Tombstone. He had plenty of money to spend around town, and this made him popular among locals. He was also a loudmouthed braggart and, more than anyone else, had instigated the fateful showdown with the Earp brothers and Doc Holliday in Tombstone on October 26, 1881.

When the shooting started, Ike ran away and hid, leaving his younger brother Billy to die. Interestingly, the Earps and Doc Holliday might have been charged with murder had Ike not testified for the prosecution. He got on the stand and with his outlandish tall tales snatched defeat from the jaws of victory for the prosecution. But that’s a story for another time.

No doubt, despite his popularity, Ike had many character flaws. Noted Tombstone historian Ben Traywick describes him as “a born loser.”

Ike Clanton moved his rustling operation from Tombstone to Springerville. In 1887, he was running away from another confrontation when he was mortally wounded. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

There was so much litigation over rustling in Apache County that Ike Clanton was probably not a high priority. As he did in Tombstone, Ike passed himself off as a successful businessman. He had a lot of money to throw around, and that was good for business.

Other members of the gang included Lee Renfro, G.W. “Kid” Swingle, Longhair Sprague, Billy Evans (who called himself “Ace of Diamonds”) and the Clantons’ brother-in-law, Ebin Stanley.

On Christmas Day 1886 in Springerville, Evans, wanting to see “if a bullet would go through a Mormon,” shot and killed Jim Hale in cold blood. Apparently Hale had incurred the wrath of the outlaws earlier after he helped identify some livestock they’d stolen.

Five days later, the St. Johns Herald wrote of the killing, “During a holiday jollification in Springerville on Christmas Day, the ordinary amusement of pistol shooting was indiscriminately indulged in, and the town ventilated with bullets. Mr. Hale, who was said to have been among the celebrators was shot through the body, from which death ensued.”

The Clantons’ downfall in Apache County began a few weeks earlier on November 6 with the shooting of a local rancher named Isaac Ellinger at the Clanton ranch. Ellinger and a friend, Pratt Plummer, had ridden to the ranch and had dinner with the Clanton brothers and Lee Renfro. Afterward, Ellinger, Ike and Renfro went into another cabin and were having a conversation when Renfro suddenly pulled his pistol and shot the rancher.

After the shooting, Ike and Fin assured Renfro they were his friends and there was no need to make a hasty exit.

However, when Plummer jumped on his horse and rode for Springerville, Renfro mounted his horse and fled the scene.

As he lay dying, Ellinger called the shooting “coldblooded murder,” saying he had no idea Renfro was going to shoot him. He died four days later.

William Ellinger, Isaac’s brother, was one of the biggest cattlemen in the West, owning ranches in several states and territories. He was a member of the Apache County Stock Association and had a lot of political clout in the area.

Isaac managed his older brother’s ranch and was also a member of the association. His murder would set in motion a strong effort on the part of the association to eliminate the Clanton gang.

In April 1887, the Apache County Stock Association convened in St. Johns and hired a Pinkerton detective to keep an eye on Andy Cooper’s gang. At the same time, Sheriff Owens dispatched Apache County deputies Albert Miller and Rawhide Jake Brighton to go after the Clantons. Brighton, along with being constable at Springerville, was a range detective enforcing the law with a mail-order detective’s badge.

Originally, on the recommendation of Undersheriff Joe McKinney, Owens had hired the famous former Texas lawman Jeff Milton to go after the Clantons, but at the last minute, he accepted a job as customs officer in southern Arizona.

In May and June 1887, several grand jury indictments were brought against the Clantons and their friends. Most of them involved the murder of Isaac Ellinger. One of the warrants charged Lee Renfro with the murder of Ellinger.

Six-gun justice was closing in on the outlaws. A July 9 edition of the Albuquerque Morning Democrat wrote a detailed description of the gunfight at Eagle Creek, stating that Billy Evans, aka Ace of Diamonds, and Longhair Sprague were believed to have met their deaths at a ranch owned by Charlie Thomas in the Blue River country of eastern Arizona. The two, along with either Lee Renfro or Kid Swingle, had ridden into the ranch and, after enjoying the rancher’s hospitality, left the following morning, taking with them some of their host’s horses.

Thomas and two friends picked up their trail and caught up with the rustlers at the mouth of Eagle Creek. Evans and Sprague pulled their guns and opened fire on the ranchers, who returned fire, killing both rustlers. The third rustler, probably Renfro, escaped.

The St. Johns Herald had a different take, claiming the story was a hoax conjured up by friends of the outlaws in order to give them time to escape. Still another twist of the tale claimed the story was made up to protect the posse as to the identity of the person who was actually gunning down the rustlers.

Soon after the gunfight at Eagle Creek, the law finally caught up with Lee Renfro along the border of Graham and Apache Counties. A “secret service” officer, in the employment of a cattlemen’s association, recognized him and attempted to make an arrest. Renfro went for his gun, and the officer shot him down.

“Did you shoot me for money?” the dying outlaw asked.

“No, I shot you because you resisted arrest,” he replied. The mysterious “secret officer” was the ubiquitous Rawhide Jake Brighton.

About that same time, it was reported that the infamous horse thief Kid Swingle was found hanging from the limb of a tree.

According to reports, Brighton and Albert Miller rode south of Springerville into the Blue River country near the Arizona–New Mexico border looking for Ike and his friends. After three days of hard riding, they stopped to rest at the ranch of James “Peg Leg” Wilson on Eagle Creek. They spent the night there, and the next morning, while they were having breakfast, Ike Clanton rode in. Brighton recognized him and went to the door.

Suddenly Ike wheeled his horse around and bolted toward a thick stand of trees nearby. At the same time, he jerked his Winchester from its scabbard and threw it across his left arm.

Brighton fired, hitting Ike under his left arm, passing through his body and exiting on the right side. Brighton jacked another cartridge into his rifle and fired again, hitting the cantle of Ike’s saddle and grazing his leg. He fell from the saddle and was dead by the time the officers reached him.

Afterward, Wilson rode to the nearby Double Circle Ranch, where he found four of Ike’s friends, who returned with him to identify the body.

Ike’s body, along with his spurs and pistol, was wrapped in a piece of canvas and buried at the Wilson ranch.

Earlier that year, in April, Fin Clanton had been arrested for rustling and jailed in St. Johns and was still behind bars when Ike was run to the ground. Otherwise, he might have met the same fate as his brother. Fin was convicted in September and sentenced to ten years at the territorial prison at Yuma but was released after serving only two years.

Ike and Fin’s brother-in-law, Ebin Stanley, was given sixty days to get out of Arizona. He and his wife packed their belongings and moved to New Mexico.

Whether or not Ike was “resisting arrest” when he was killed is still debated by historians. Despite the official report, there are some today who insist that Brighton was a hired assassin who shot Ike in the back as he was running away. The assassination of known rustlers wasn’t all that uncommon in the Old West, where justice was sometime hard to come by. Ike had cleverly managed to elude the law for several years before he was finally driven out of Cochise County.

“Shot while resisting arrest” was a phrase often used to justify exterminating an evasive outlaw who’d managed to escape prosecution by legal means. Towns and cities in the West frequently resorted to vigilante justice when they felt the law was unable or unwilling to protect them. Big ranchers and cattlemen’s associations across the West oftentimes hired gunmen to rid their ranges of livestock thieves. The Johnson County War in Wyoming and the story of Tom Horn are classic examples. The legendary Cochise County sheriff John Slaughter acted as judge, jury and executioner more than once.

Author Steve Gatto said it best when he wrote, “The last man standing gets to tell the tale.” And so it is.

Although Owens wasn’t present at the last roundup of the Clantons and their cohorts, his dragnet was putting a dent in the outlawry in Apache County, and the bad guys were heading for greener pastures.

The other band of outlaws on Owens’s hit list was Mart “Old Man” Blevins and his four sons, Andy, Charley, Hamp and John. There was also a younger brother, fifteen-year-old Sam Houston. Twenty-five-year-old Andy, the eldest, used the alias surname Cooper and was singled out as the leader of the gang.

Andy Cooper came to Arizona from Mason County, Texas, sometime in 1884 and quickly saw the lucrative opportunities in the business of stealing livestock. He encouraged his father to bring the rest of his family to Arizona. They arrived in 1886 and set up their “ranching” operations.

The “Old Man,” who was only forty-seven, had a fondness for acquiring good horseflesh without paying for it and probably thought the change of scenery would do him and his family good. It turned out to be a bad business decision for them all.

Soon they were driving stolen horses from Utah and Colorado to their ranch on Canyon Creek, ninety miles south of Holbrook.

The outlaws’ operations in the area crossed county lines. At the time, Pleasant Valley was part of Yavapai County, and the simmering war between the Grahams and Tewksburys was heating up. Some of the outlawry associated with the feud was spreading into Apache County. It’s been said that although Owens remained neutral in the feud, he favored the Tewksburys. The forthcoming shootout in Holbrook would pit the Apache County sheriff against a faction of the Grahams.

In 1887, Holbrook, a town of some 250 residents had a dozen or so frame shacks lined up along Center Street, which paralleled the Santa Fe railroad tracks. The Little Colorado River or Rio Chiquito Colorado ran just south of town. Half a dozen saloons, two or three stores and a post office lined the south side of the tracks. On the north side was a blacksmith shop, livery stable and several small houses. One of those had been recently occupied by the Blevins family.

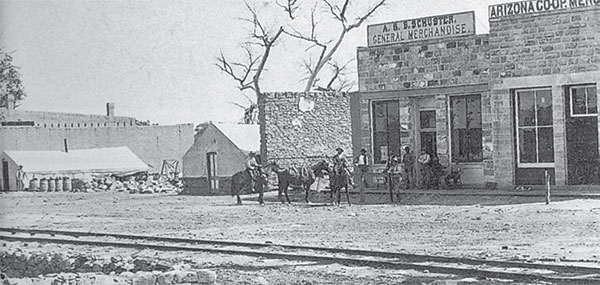

Andy “Cooper” Blevins looks like a clean-cut youngster, but looks are deceiving; he was a coldblooded killer. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

For Sheriff Commodore Perry Owens, events were moving rapidly toward his rendezvous with destiny. They say for a gunfighter to get into Valhalla he must have a strong antagonist. That antagonist would appear in the form of a vicious killer named Andy Cooper.

Andy was born on the family ranch near Austin, Texas. Mean enough to eat off the same plate with a rattlesnake, he’d been in trouble with the law since early in his youth. He’d been run out of Indian Territory for peddling whiskey to Indians, and Texas lawmen wanted him for murder and robbery. One story had him making a daring escape from the Texas Rangers by jumping from a train.

The St. Johns newspaper accused him of murder, rustling and forcing small ranchers off their land. The paper also accused him of burning down a church. In May 1887, a group of Mormon ranchers accused him of stealing a herd of cows and selling them in Phoenix.

Two years earlier, Andy had murdered a Navajo youngster and managed to avoid arrest. He killed two more Navajos before being forced to hide out in New Mexico until things cooled off in Apache County. The white citizens of Apache County were beginning to fear that the Navajos would begin taking vengeance on innocent settlers.

According to L.J. Horton’s memoirs, Andy robbed and murdered a sheepherder in cold blood near Flagstaff. He then ambushed and killed a witness named Converse and the two lawmen who were pursuing him. Andy netted thirty dollars and, in the process of covering any trace of being linked to the crime, killed four men.

According to an article in the St. Johns Herald , Cooper’s band openly boasted that peace officers were afraid of them.

Cooper was also a bully. He especially enjoyed browbeating peaceful Mormons in the Rim Country. One story had him ordering a family off their land along Canyon Creek at gunpoint because he wanted the place to rebrand stolen livestock. Other examples of his hooliganism were the pistol-whipping of an unarmed sheepherder and stealing of Navajo horses.

Andy Cooper Blevins wasn’t the only one to run afoul of the law. Hamp Blevins, the family’s third-born, had done time in the Texas state pen for horse stealing.

In June, Andy, Charley and Hamp left the Canyon Creek ranch and rode to Holbrook for supplies. The morning they left, Mart Blevins rode out to look for some horses that had been turned out to graze in the canyon. The horses were gone, and he suspected they’d been stolen. He rode back to the house and told his son John he was going in pursuit while the trail was still warm. On the trail, he met a neighbor, and the two went searching for the missing horses. The neighbor returned four days later and told Mrs. Blevins that Old Man was still trailing the animals. Blevins never returned, and his body was never found, but it was suspected that Tewksbury partisans had killed him. It was also claimed they fed his body to the feral hogs that roamed the Rim Country. These were not ordinary hogs, as they were as wild as deer, as big as black bears and as mean as badgers.

The Blevins boys returned from Holbrook and searched the area but found no trace of their dad.

In early August, Hamp joined a small group of Hash Knife cowboys and rode into Pleasant Valley, ostensibly to search for Old Man Blevins. On the ninth, they rode into the old Middleton ranch on Wilson Creek, where they ran into some Tewksbury partisans, got into an exchange of angry words and a gunfight ensued. When the smoke cleared, two men, including Hamp Blevins, were dead.

On September 2, looking for revenge, Andy Cooper and some Graham partisans ambushed a party of Tewksbury partisans in Pleasant Valley, brutally murdering John Tewksbury and Bill Jacobs. Two days later, Andy was in Holbrook boasting that he had “killed one of the Tewksburys and another man whom he didn’t know.”

Will C. Barnes, in his book Apaches and Longhorns , mentions that Sheriff Owens had held a warrant for Andy’s arrest for horse stealing for some time but had been reluctant to serve it. Barnes claimed they were “range pals,” and “it was common belief that he was avoiding the arrest, feeling sure that one or the other would be killed. Perhaps both, for each man was a dead shot.”

The Apache County Stock Association had sworn out the warrant for Cooper’s arrest. Barnes was secretary and treasurer of the association. The board was meeting in St. Johns and was aware of the unserved warrant. They summoned Owens and demanded to know why it hadn’t been served. Owens said he didn’t know where to find Cooper.

According to Barnes, he informed the sheriff that he’d seen the outlaw in Holbrook. Owens was then told that if he didn’t arrest Cooper in the next ten days they would remove him from office.

Soon after, the ubiquitous Barnes was working cattle about ten miles from Holbrook when he got word of the pending showdown between the sheriff and Andy Cooper. He hightailed it into town to witness the action.

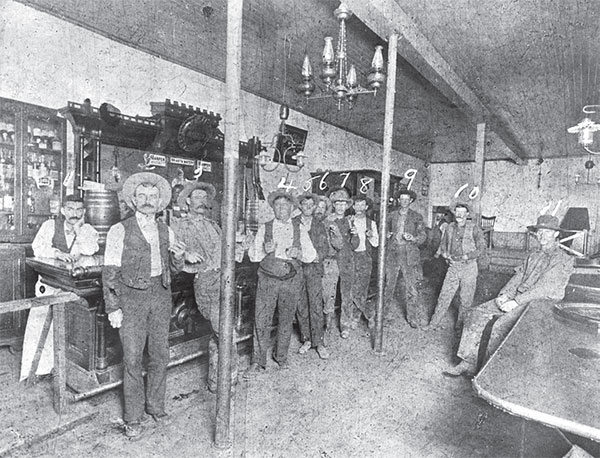

Holbrook during the 1880s. Sheriff Commodore Perry Owens had his shootout with the Blevins boys at a house located near where the photographer was standing. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

“I wanted to see how the little affair would come off,” he wrote.

Riding cross county, he arrived in Holbrook just prior to Owens.

The sheriff rode in from the south on a blazed-face sorrel, pausing on a small hill outside of town to plan his next move.

He entered town, put up his horse at Sam Brown’s Livery Stable and then walked over to the drugstore owned by Deputy Sheriff Frank Wattron. John Blevins, one of Andy’s brothers, was at the stable when the sheriff arrived. He slipped away to warn his brother.

Meanwhile, Barnes made his way to the platform of the railway station, which had a commanding view of the Blevins house.

“There I sat down on a bench,” he wrote, “and waited for action.”

Justice D.G. Harvey was also present. He later testified that, upon arriving, Owens asked if Cooper was in town. When told he was, Owens said, “I am going to take him in.” The sheriff then calmly proceeded to clean and reload his pistol.

Sam Brown offered to go along with Owens to make the arrest of Andy but was told, “If they get me, it’s alright. But I want you and everyone else to stay out of it.” Owens then cradled his Winchester in his arm and started for the Blevins house on Center Street, about one hundred yards away. A saddled dun was tied to a cottonwood tree a few feet from the house. Barnes described the house as L-shaped with a front porch from which two doors opened.

As Owens approached, he saw a man watching him from an open door. As he drew closer, the door slammed shut. It was now about four o’clock in the afternoon.

The Blevins house on Center Street in Holbrook is today a historic shrine. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

When John Blevins returned to the house with word of Owens’s arrival, he was told by his older brother to go get his horse from the stable and bring it to the house. John did as he was told, tying the dun outside the house. Andy was throwing a saddle on the animal when he looked up and saw Owens approaching. He turned quickly and went into the house. Inside were two other men, John Blevins and Mote Roberts, along with young Sam Houston Blevins. Also present were the widow Mary Blevins; her nine-year-old daughter, Artemisia; Eva Blevins, John’s wife; their infant son; and Amanda Gladden, along with her infant baby and her nine-year-old daughter.

Frank Wattron, like several others, wanted a front-row seat. He hustled over to the railroad station and sat down next to Barnes.

What happened next is perhaps best described in Commodore Perry Owens’s own words:

I came in town on the fourth instant, went to Mr. Brown’s Stable, put up my horse and about that time Mr. Harvey and Mr. Brown came into the stable. I spoke something of Mr. Cooper, and they told me he was in town, that he comes in this morning. I told Mr. Brown that I wanted to clean my six shooter that I was going to arrest Cooper if he was in town. I came in to clean my six shooter. Someone came after a horse in the corral [John Blevins].

Mr. Brown says to me, “That fellow is going to leave town.”

I told Mr. Brown to go saddle my horse; if he got away I would follow him. I did not wait to clean my pistol. I put it together without cleaning it, went into the stable, and asked the man who cleans the horses if that man had saddled that dun horse. He said no .

I says, “Where is his saddles?”

He says, “His saddle is down to the house.”

I asked him where the house was. He told me the first one this side of the blacksmith shop. I went and got my Winchester and went down to arrest Cooper. Before I got there, I saw someone looking out at the door. When I got close to the house, they shut the door. I stepped up on the porch, looked through the window and also looked in the room to my left. I see Cooper and his brother [John] and others in that room. I called to Cooper to come out. Cooper took out his pistol and also his brother took out his pistol. Then Cooper went from that room into the east room. His brother came to the door on my left, took the door knob in his hand and held the door open a little. Cooper came to the door facing me from the east room. Cooper held this door partly open with his head out .

I says, “Cooper I want you.”

Cooper says, “What do you want with me?”

I says, “I have a warrant for you.”

Cooper says, “What warrant?”

I told him the same warrant that I spoke to him about some time ago that I left in Taylor, for horse stealing .

Cooper says, “Wait.”

I says, “Cooper, no wait.”

Cooper says, “I won’t go.”

I shot him .

This brother of his to my left behind me jerked open the door and shot at me, missing me and shot the horse which was standing side and a little behind me .

According to Barnes’s account, John Blevins fired at Owens with a pistol from about six feet away. He missed, and the bullet hit Cooper’s horse squarely between the eyes. The animal jerked back, breaking the reins and galloped off a few yards down the street before dropping dead.

“I whirled my gun and shot at him,” Owens continued, “and then ran out in the street where I could see all parts of the house.”

John Blevins slammed the door after firing his pistol. Owens fired through the door, and the bullet tore into Blevins’s shoulder, taking him out of the fight.

I could see Cooper through the window on his elbow with his head towards the window. He disappeared to the right of the window. I fired through the house expecting to hit him between the shoulders .

Owens fired again, this time sending a bullet crashing into Cooper’s hip. “I stopped a few moments,” he continued.

Some man [Mote Roberts] jumped out of the house on the northeast corner out of a door or window, I can’t say, with a six shooter in his right hand and his hat off. There was a wagon or buckboard between he and I .

I jumped to one side of the wagon and fired at him. Did not see him anymore .

Owens’s fourth bullet passed through Roberts’s chest, wounding him fatally.

I stood there a few moments when there was a boy [Sam Houston Blevins] jumped out of the front of the house with a six shooter in his hands. I shot him. I stayed a few moments longer. I see no other man so I left the house. When passing by the house I see no one but somebody’s feet and legs sticking out the door. I then left and came on up town .

When it was clear no one else was coming out of the house, Owens turned and walked back toward the livery stable. The gunfight lasted just three minutes. Several townspeople suddenly appeared on the street. Local justice of the peace A.F. Banta asked, “Have you finished the job?”

Owens looked at him and curtly replied, “I think I have.”

In the span of a few short minutes, Owens had faced four guns. Only one shooter, John Blevins, had gotten a shot off, and in his haste, he missed. Owens fired five times. He didn’t miss. Sam Houston Blevins died instantly of a bullet in the chest. Mote Roberts lingered a few days before expiring, and John Blevins eventually recovered from a shoulder wound. Andy Cooper lived a few hours, suffering painfully from his wounds before giving up the ghost, and perhaps had some time to reflect on his savage life.

Slain outlaws often grow halos. Following the “street fight” in Tombstone, Billy Clanton and the McLaury brothers were pictured in death by their supporters as unarmed, happy-go-lucky cowboys just having a little fun. It was the same with the Blevins boys. Listening to members of the family testify at the inquest, one would think the boys in the house were all unarmed and discussing what they’d learned in Sunday school class that morning when Sheriff Owens stepped up on the porch.

At the inquest that followed, family members and friends saw the fight differently, claiming Andy was unarmed, which seems odd considering he knew the sheriff was coming.

Amanda Gladden, who was inside the house, claimed she never saw any of the Blevins men holding weapons.

Mote Roberts lingered in pain for eleven days before expiring. He lived long enough to testify at his own inquest. Roberts swore he was unarmed and, at the first sound of gunfire, dove out the window to escape.

John Blevins swore he never fired a shot.

Mary Blevins, Sam’s mother, said, when asked if he had a pistol, “Not that I know of; if he did I don’t remember it.”

Witness D.B. Holcomb testified about the shooting of young Sam Blevins: “If the boy had a pistol I did not see it.”

But Dr. T.P. Robinson, who attended the youngster, testified he was holding a pistol.

Contrary to Mote Roberts’s sworn testimony, there is evidence he dove out the window holding a pistol.

John Blevins explained the spent shell in his revolver occurred when he fired a round as he was riding into town with Andy.

The testimony of several other reliable witnesses, including Frank Wattron, Henry F. Banta and Will Barnes, supported the sheriff. In the end, an inquest exonerated Sheriff Owens in the killing of all three men.

A few days later, the St. Johns Herald said, “Too much credit cannot be given Sheriff Owens in this lamentable affair. It required more than ordinary courage for a man to go single-handed and alone to a house where it was known there were four or five desperate men inside, and demand the surrender of one of them…outside of a few men, Owens is supported by every man, woman and child in town.”

Today historians still differ on whether Sheriff Owens was a lawman doing his duty or an executioner; however, most historians generally accept Owens’s account of the fight.

Rim Country historian Jayne Peace Pyle has spent years studying the Pleasant Valley War and is no fan of Owens. She told the author, “Owens and Andy Cooper Blevins were comrades in crime when Cooper Blevins first came to Arizona. Owens had told Andy that he would not serve that warrant on him. When Owens knew he had to serve the warrant to keep his job, he knew he had to kill Andy—and kill without warning—which he did, or Andy would have killed him.”

She makes a good point when she says, “Personally, I think it was terrible for Owens to go to Mrs. Blevins’s home and shoot into a house with women and children inside. Surely he could have cornered Andy somewhere outside. One of the babies was so covered with blood, they thought it had been shot! I know a lot of people see Owens as a brave man, but I don’t.”

Barnes offered a description of the interior of the Blevins house:

The interior of the cottage was a dreadful and sickening sight. One dead boy, and three men desperately wounded, lying on the floors. Human blood was over everything. Two hysterical women, one the mother of two of the men, the other John Blevins young wife, their dresses drenched with blood, were trying to do something for the wounded .

Poor Mary Blevins was the real casualty of war. Matriarch of the family, she had lost her husband, Mart, and son Hamp a few weeks earlier in the Pleasant Valley Feud. Two more sons died in the fight with Sheriff Owens, and another was seriously wounded. A month later, another son, Charley, would be gunned down by a posse while resisting arrest outside the Perkins Store in Pleasant Valley.

In her book, Women of the Pleasant Valley War , Jayne Peace Pyle writes about Mary Blevins’s losses:

Her world was turned upside down. I think almost any woman and some men could identify with her feelings. Mary’s loss was so great! I think this is the one thing that turned public opinion against C.P. Owens. He attacked a house full of women and children. Anyone of them could have been killed .

John Blevins, the lone survivor of the fighting Blevins family, was sentenced to five years in the Yuma Territorial Prison for his part but was released without doing time. He later became a deputy sheriff and, in 1901, was shot in the shoulder by drunken soldiers just a few feet from the old Blevins house. He eventually moved to Phoenix, where he engaged in ranching and, in 1928, was appointed Arizona State Cattle Inspector. Two years later, he was killed by a hit-and-run driver near Buckeye.

Author Jo Baeza, who’s been writing about the history of the area for more than fifty years, is a great admirer of Owens:

I don’t agree with those writers who criticize Owens. He will always be a hero to me. And, I don’t agree with a lot that Will Barnes wrote because he liked to embellish. I do have faith in court records, testimonies, and men like Frank Wattron .

One of the things I learned after talking to many people back 50 years ago is how much the Mexican and Mormon people loved Owens. He was their protector at a time when everyone was persecuting them to get their land and water rights .

Just for fun he used to put on shooting exhibitions for the LDS settlers on July 4th . He’d shoot his initials in a tree trunk while riding at a gallop. No matter what opinion people have of him, there is no doubt he was one of the best marksmen in the West .

The courage of Commodore Perry Owens cannot be disputed. He refused assistance, including that of his deputy Frank Wattron, and went to arrest Andy Cooper alone. He wound up in a gunfight with four men and dispatched them all singlehandedly.

As so often happened in the Old West, citizens in need of law and order cried out for a fearless gunfighter to come riding in and rid the place of the bad guys. And after the six-gun Galahad’s work was finished, he became something of an embarrassment to the community. Civic leaders in Apache County became antagonistic toward their sheriff after the gunfight at the Blevins house.

A story is told that one time, after the board of supervisors refused to pay money owed, Owens walked into a meeting, drew his revolver and demanded he be paid. The nervous supervisors paid up without delay.

“I don’t believe the story that he pulled a gun on the board of supervisors to get his pay,” says Baeza.

He would not have done that. He didn’t pull a gun on anybody unless he intended to shoot them. It’s true they withheld his pay to try to get rid of him after the Blevins shootout, but they didn’t know him very well. Jake Barth told me this story and he would have known. He even showed me the room Owens had before they tore down the old hotel. An upstairs room overlooking the main street. Owens boarded at the Barth Hotel in St. Johns. When the supervisors met, he paid his bill at the hotel, packed a horse with his belongings, armed himself, and rode up to the courthouse, leaving his horse outside as if he was ready to get out of town. They got the message and paid him what they owed him. After he got paid, he rode back to the hotel, unloaded his stuff and moved back in. As far as I know that ended the games the supervisors were playing with him. It also shows Owens had a sense of humor .

Sheriff Commodore Perry Owens didn’t always find success in his pursuit of outlaws. An example was Red McNeil, a reckless, carefree Hash Knife cowboy who, at the age of twenty, decided to become a desperado. He might not be remembered in the annals of outlawry if he hadn’t had a propensity for leaving clever poems at the scene of his crimes. Usually they were meant to insult the lawmen in pursuit. Red was believed to have come from an affluent family back east and had even gone to college. He once confided to a friend that he’d been educated to become a Catholic priest.

In early 1888, Red was in jail in Phoenix on a charge of horse stealing but escaped and stole another horse. He was recaptured and locked up in Florence but got away again. This time Red headed for Apache County, where he took a load of buckshot while attempting to rob Schuster’s merchandise store in Holbrook. Red was making his getaway but still found time to pen this poem and tack it to a tree on the banks of the Little Colorado River:

I’m the prince of the Aztecs;

I am perfection at robbing a store;

I have a stake left me by Wells Fargo ,

And before long I will have more .

There are my friends, the Schusters ,

For whom I carry so much lead;

In the future, to kill this young rooster ,

They will have to shoot at his head .

Commodore Owens says he wants to kill me;

To me that sounds like fun .

’Tis strange he’d thus try to kill me ,

The red-headed son-of-a-gun .

He handles a six-shooter neat ,

And hits a rabbit every pop;

But should he and I happen to meet ,

We’ll have an old-fashioned Arkansas hop .

Not much chance for a Pulitzer Prize here but not bad for an outlaw on the run.

Red McNeil crossed the border and hired out at the WS Ranch in New Mexico. The affable redhead made friends easily, entertaining the cowhands with his mouth harp and clog dancing. Everyone thought he was a great guy until he suddenly vanished, taking with him the ranch’s prize thoroughbred stud.

Late in 1887, near the Arizona–New Mexico border, Sheriff Owens was still searching for McNeil for the Shuster’s robbery. He rode into a cow camp one night, asking if anyone was acquainted with the redheaded outlaw. None of the cowhands could rightly say they’d had the pleasure of Red’s acquaintance. The lawman was invited to stay the night, and having no bedroll, one of the punchers generously offered to share his blankets.

The cowhands rode out at daybreak, leaving Owens asleep in camp. He awoke to find a note in familiar handwriting from the man who shared his bedroll. Despite being in a rush, he did pen a short good-natured poem to the sheriff:

Pardon me, sheriff

I’m in a hurry;

You’ll never catch me

But don’t you worry .

Red McNeil

Sheriff Owens’s reaction to this affront is not known.

In 1889, the law finally caught up with the popular, devil-may-care outlaw Red McNeil. He was arrested and convicted on a charge of train robbery and served ten years in prison. In prison, he educated himself to be a hydraulic engineer and went on to live a respectable life. Many years later, he returned to Holbrook and visited Schuster’s store. The former outlaw fully hoped there were no hard feelings and was assured the past was all water under the bridge.

After his term expired in January 1889, Owens returned to his ranch near Navajo Springs and raised prize horses. He was a special agent for the Atlantic and Pacific (Santa Fe) Railroad for a time and then an express messenger for Wells Fargo. Later he served as a U.S. deputy marshal for several years. In 1894, he made an unsuccessful run for Apache County sheriff, and the following year he was appointed sheriff of newly created Navajo County, carved from the western part of Apache County. He made a bid for a full term in 1896 but lost in the general election.

Owens was an honest, dutiful lawman who accomplished his primary mission—that of running the rustler gangs to the ground. Unfortunately, he was also perceived by many as a man-killer, and this no doubt hurt his political career. He wasn’t the first “good man with a gun” who was brought in to bring law and order only to be turned away by the good citizens when his services were no longer needed.

In 1902, he settled in Seligman, opened a saloon and married Elizabeth Barrett. He’d hung up his shooting irons by this time and ran a successful business until he died on May 10, 1919.

There’s no doubt Commodore Perry Owens was a man with the bark on. Will Barnes pretty well summed up his “fifteen minutes of fame” in Holbrook that September day when he wrote, “In all the wild events in Arizona’s wildest days there is nothing to surpass this affair for reckless bravery on the part of a peace officer.”