The hard-riding Arizona Rangers were “darlings of the press,” and this is one of their better-known photographs of the Wilcox patrol. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

8

BURT MOSSMAN

CAPTAIN OF THE ARIZONA RANGERS

Around 1900, while the territory strove for statehood, vicious bands of outlaws sullied Arizona’s reputation. One measure meant to whip the bandits and to further statehood efforts was the formation of the Arizona Rangers. Their first leader was an Illinois native who began working as a cowhand when he was only fifteen years old.

Arizona greeted the twentieth century as a frontier Jekyll and Hyde. On one hand, communities like Phoenix, Prescott and Tucson were becoming modern cities. Churches and schools outnumbered the bawdy houses and saloons, a sure sign that civilization was making progress. Law and order generally prevailed. In 1907, both gambling and prostitution were outlawed.

On the other hand, the rural, mountainous regions still provided a refuge for desperadoes. Large bands of outlaws holed up in the primitive wilderness of the White Mountains. Mexico was a sanctuary for border bandits. Arizona was the last of the wild places. Outlaws on the run in other territories and states could find a safe haven in the labyrinth of canyons and brooding mountains. Towns were few and far between, and roads were mostly cattle trails.

With the completion of the Santa Fe line in the north and the Southern Pacific in the south, stage robbers turned to a new line of work. Between 1897 and 1900, there were six train robberies on the Southern Pacific alone. Bands of rustlers boldly stole cattle in broad daylight, driving small outfits out of business. Payrolls for the mines were being robbed on a regular basis.

County sheriffs had no jurisdiction outside their districts. Once an outlaw crossed a county line, he was home free. During the 1880s, there was a large outcry from ranching and mining interests for a territorial police modeled after the famous Texas Rangers. By the turn of the century, politicians were trying to impress upon the U.S. Congress the fact that Arizona was ready for statehood. Many in Congress didn’t think the Arizonans should be admitted until they did something about the lawlessness.

In March 1901, the territorial legislature passed a bill to raise a quasi-military company of rangers who not only could shoot straight and fast but also ride hard and long. Funding for the ranger force would come from a territory-wide tax.

The force would consist of fourteen men, including a captain and a sergeant. The term of enlistment was for one year; the captain would receive $125.00 a month, the sergeant was paid $75.00 and the twelve privates would each be paid $55.00 a month. Rangers had to provide their own horses, tack and weapons. With typical generosity, the politicians also allowed each ranger $1.50 a day to feed both him and his horse.

On March 19, 1903, rangers were expanded to twenty-six men. The captain’s pay was raised to $175 a month, a lieutenant was added and received $130, two sergeants at $110 and twenty-two privates at $100 a month. Officially, the rangers’ duties were to assist local law enforcement agencies, prevent train robberies and run the rustlers out of the territory.

The hard-riding Arizona Rangers were “darlings of the press,” and this is one of their better-known photographs of the Wilcox patrol. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

They were placed under the command of the governor, and this created problems from the beginning. Territorial governors were appointed in Washington, while legislators were elected locally. Most governors were Republicans, while the Democrats always controlled the legislature. Many in the legislature saw the rangers as the governor’s private police force. Another problem that plagued the rangers from the beginning was most of the outlaws were operating in the rugged mountains of eastern Arizona or along the Mexican border.

Other counties, such as the populous Maricopa County, had little need for the free-ranging lawmen and resented having to share the tax burden. There was also some professional jealousy. The activities of the colorful rangers were closely followed by an adoring press. Local lawmen, who shared the same dangers while rounding up desperadoes, found themselves being left out of the newspaper stories, and they naturally felt resentful.

Still another problem the rangers would face during their tenure was image. They were a rough-and-ready bunch, and they had to be as tough as the desperate men they pursued. Consequently, some got into scrapes that sometimes went beyond their duties as lawmen and brought bad publicity to the entire force. If the rangers were going to be effective, they would need a captain who could lead and hold the respect of his young hellions.

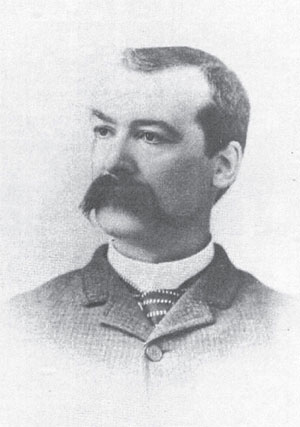

Captain Burton C. Mossman was the first captain of the Arizona Rangers. His last adventure during his tenure was the daring capture of the notorious Augustine Chacon. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

Burt Mossman was Governor Nathan Oakes Murphy’s choice to be captain of the Arizona Rangers. The rawhide-tough cowman had made quite a reputation for himself when he ran the famous Hash Knife outfit in northern Arizona.

Mossman’s life reads like something out of a Louis L’Amour novel. He was the son of a Civil War hero, a descendant of Scots-Irish ancestry, that adventuresome breed who carved out a niche of history on the American frontier a century earlier. He stood five feet, eight inches, weighed 180 pounds and was of stocky build, with broad shoulders. By the time he was fifteen, Mossman was drawing pay as a working cowboy in New Mexico.

As a young cowboy, Mossman earned a reputation as a quick-tempered, wild and restless youth who’d fight at the drop of a hat. He was also very dependable and honest, something that earned the respect of the ranchers for whom he worked. Once he walked 110 miles across a dry, burning desert to deliver an important letter for his boss. He walked the forty-seven-hour journey because he thought the land was too dry for a horse to travel.

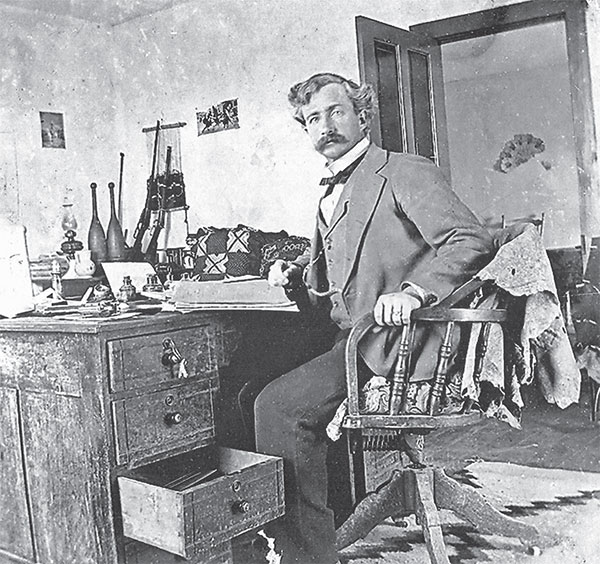

Prior to becoming captain of the Arizona Rangers, Mossman was superintendent of the famous Aztec Land and Cattle Company, better known as the Hash Knife Outfit. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

By the time he was twenty-one, Mossman was foreman of a large ranch in New Mexico that ran eight thousand head of cattle. At twenty-seven, he was managing a big outfit in the Bloody Basin in Arizona’s rugged central mountains. Three years later, he was named superintendent for the troubled Aztec Land and Cattle Company, better known as the Hash Knife Outfit. The fabled Hash Knife had been one of the biggest cow outfits in the West. But now it was on the verge of bankruptcy when he was called in to try and keep it from going belly up.

It was while running the Hash Knife that Burt Mossman achieved his greatest fame up to that time. The eastern-owned outfit had been running as many as sixty thousand head of beef over two million acres. Gangs of rustlers, both in the employ of the company and those who set up maverick factories on the fringe, had been stealing the ranch blind. The ranch had been frustrated in its attempts to stop the rustling by locals who resented large, absentee ownership and who, because of land grant advantages, were able to graze their cattle free on the public domain. Consequently, local juries were prone to find defendants not guilty. Also the rustlers were able to get friends on the jury to disrupt things, causing a mistrial or hung jury. In fourteen years of trying, the Hash Knife hadn’t been able to get a single conviction.

Mossman didn’t waste time settling into his new job. On his first day, the scrappy cowman captured three rustlers and tweaked the nose of Winslow’s town bully. Then he fired fifty-two of the eighty-four cowboys on the Hash Knife payroll and installed trusted cowmen as wagon bosses. He visited local leaders in the community and convinced them to take a stand against cattle rustlers. Soon, he had the outfit turning a profit again.

But Mossman couldn’t control the weather, the cowman’s greatest nemesis. A prolonged drought, followed by a calamitous blizzard, finished off the company in 1901.

Despite the failure of the Hash Knife, Mossman earned a reputation as a formidable foe of cattle rustlers, along with being a smart, savvy businessman. After the Hash Knife, he headed for Bisbee, where he opened a beef market with Ed Tovrea, but he didn’t stay in that business long. When the Arizona Rangers were organized, Governor Murphy knew it would take a special kind of man to manage more than a dozen energetic, high-spirited lawmen, and Mossman was that man.

Mossman agreed to a one-year enlistment, and though his tenure was brief, the rangers had some of their greatest success during that first year. He located the ranger headquarters in Bisbee and set about recruiting his force. It wasn’t hard. Every young man in the territory with a spirit of adventure wanted to ride with Mossman’s rangers. He selected his men carefully, dressed them as working cowboys and had them hire out for outfits where rustling had been a problem. They operated in secrecy as undercover agents infiltrating cliques of rustlers. They kept their badges concealed and pinned them only when an arrest was imminent.

The rangers met their greatest challenge early on when they took on a band of wild marauders known as the Bill Smith Gang. The outlaws had been run out of New Mexico and set up new operations at Smith’s widowed mother’s place near Harpers Mill on the Blue River.

Taking on Bill Smith and his band of renegades was a sad and disappointing experience for the new force. Bill Smith gunned down ranger Carlos Tafolla and Apache County deputy sheriff Bill Maxwell near the headwaters of the Black River in eastern Arizona. Mossman was determined to run the gang into the ground and made a gallant pursuit all the way to the Rio Grande but never got his man. The only satisfaction he got was the gang was driven out of Arizona for good.

Next, the rangers invaded the den of another band of cow thieves, the Musgrave Gang, led by George Musgrave and his brother, Canley. They were wanted in Texas and New Mexico for robbery and murder. The Musgraves had also ridden with the Black Jack Gang, a tempestuous band of highwaymen that had ravaged along the Arizona–New Mexico border country.

The successful raid on the outlaw band came after lawmen learned that one of the gang, Witt Neill, had a girlfriend living up on the Blue River. Then deputy sheriff John Parks received a tip that several well-armed, suspicious-looking men were seen at the mouth of the Blue River, north of Clifton. He passed the information on to Graham County sheriff Jim Parks at Solomonville and to Captain Mossman at Bisbee. Parks and Mossman rushed to Clifton and organized a posse to go after the marauders. They headed for the girlfriend’s place. Arriving late at night, the lawmen surrounded the cabin and waited for dawn. At first light, they closed in and found Neill sleeping on the porch. He awoke looking into the muzzles of several pistols and rifles. The rustler had a Winchester, a pair of six-guns and enough bullets to start a revolution tucked under the covers but wisely surrendered without a fight.

Two other members of the gang, George Cook and Joe Roberts, were spotted that same day driving some stolen horses. The posse split up and surrounded the men without being spotted. The unwary rustlers were apprehended and then hustled off to the jail at Solomonville. The pair was believed to have robbed a store in New Mexico, murdering the owner. Cook and Roberts also fit the description of two men who robbed a post office at Fort Sumner the previous January.

With the capture of one of the segundos , or leaders, and a couple of others, the Musgrave leadership was shattered and scattered, causing the gang to quit the country.

The spirit of cooperation between the rangers and the Mexican police was generally good. The Mexican forces, called Rurales, were the rangers’ counterparts. They were ably led by Colonel Emilio Kosterlitzky, one of the more remarkable men in the border country. A Russian by birth, he spoke several languages fluently and was a man of great intellect. Kosterlitzky came to Mexico as a young man and joined the ranks of the Rurales as a private. He rose to the rank of colonel in President Diaz’s feared police. A stern, no-nonsense commander, his men operated under the law of ley fugar , or “law of flight.” In other words, they brought in few live prisoners. The common practice was to say the captive was “shot while trying to escape.” It was a brutal but effective way of lowering the population of the border bandits.

The rangers and Kosterlitzky didn’t bother with the formalities of diplomatic red tape when dealing with fugitives. Kosterlitzky had appointed the rangers officers in his force. They often crossed the border into Mexico in pursuit of some outlaw, and fugitives were frequently exchanged quietly between the two groups. A wanted man in Arizona might be sitting in a cantina in Cananea thinking he was in a safe haven. He might go upstairs with some pretty señorita to have a nightcap, and the next thing he knew, he was sitting in the jail in Bisbee wondering how he got there. The young lady was working with the rangers. She’d slipped him a mickey and handed him over to the Rurales, who, in turn, hauled him to the border with a gunnysack over his head and turned him over to the rangers. Mossman learned early on that the best source of information came from the ambitious saloon girls in the border towns.

Near the end of Mossman’s enlistment as ranger captain, he was involved in a fracas one night at the Orient Saloon in Bisbee. He and ranger Bert Grover were sitting in a poker game with some $400 in the pot, which was won by a local gambler. Grover accused the gambler of cheating and jerked his six-shooter. Mossman tried to calm down his ranger just as a couple of Bisbee police arrived. When the police arrested Grover, Mossman and another ranger, Leonard Page, joined in. The donnybrook wound up in the street in front of the Orient, much to the delight of the Saturday night revelers of Brewery Gulch. Grover was finally placed under arrest and taken to jail. A few hours later, the resourceful Page purloined the keys to the jail and freed his comrade.

The citizens of Bisbee were upset by the rangers’ rowdy actions, and two hundred of them signed a petition demanding Governor Murphy relieve Mossman of his command. Most of those signing the petition, however, were barflies, tinhorns and other wretches with axes to grind who inhabited Brewery Gulch. A group of respectable citizens circulated another petition in support of Mossman.

A couple of days later, Mossman submitted his resignation to the governor. He hadn’t planned to stay in the low-paying position long when he signed on, and with his good friend Governor Murphy leaving office, he, too, might have felt it was time to move on. Also he was a typical cowhand, free and independent, and the incident in Bisbee might have soured him on public service.

During Burt Mossman’s tour of duty, the rangers put 125 men behind bars and, remarkably, considering the kinds of hard-bitten desperadoes they were dealing with, killed only one man. One ranger, Carlos Tafolla, was killed in the line of duty.

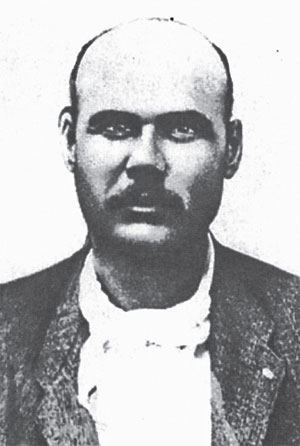

While Captain Mossman was waiting for his resignation to become effective, he needed to tie up some loose ends. During the past year, he’d become obsessed with capturing Augustine Chacon, one of the most cunning and rapacious outlaws in the border country. Chacon lived in Sonora but made periodic forays into Arizona to loot and pillage. The handsome bandito once boasted to an officer he’d killed thirty-seven Mexicans and fifteen Americans. He was looked upon in Sonora and among the Mexicans working in the mining camps of Arizona as a folk hero because he’d given the gringo lawmen such fits. But in reality, he was a diabolical killer. During the robbery of a store in Morenci on Christmas Eve 1895, he slit the throat of the shopkeeper with a hunting knife. A posse cornered him and tried to negotiate a surrender. During the parley, he shot posse man Pablo Salcito in cold blood. Salcito, who was acquainted with the outlaw, had tied a white handkerchief to the barrel of his rifle and had walked to within a few feet of Chacon when the outlaw gunned him down. In the ensuing gun battle, Chacon was wounded and captured. A Graham County jury convicted and sentenced him to hang.

Chacon escaped the hangman’s noose in Solomonville by breaking out of jail nine months before his sentence was to be carried out. The roguish bandito had a string of pretty señoritas at his beck and call. His inamorata in Solomonville managed to slip him a file concealed in the spine of a Bible. A mariachi band was doing time in the jail for some transgression so Chacon had them play a cacophony of corridos to drown out the noise while he sawed through the bars. His pretty girlfriend had flirted with the jailer on several occasions and, on the night of his escape, persuaded the love-struck fellow to take her for a midnight stroll. The jailer returned later to find his prisoner had flown the coop. During his escape to Sonora, Chacon murdered two prospectors, and for the next five years, he managed to evade both Mexican and American lawmen.

Mossman made up his mind that the capture of Augustine Chacon would be his crowning glory as ranger captain. He concocted a daring plan to slip into Sonora, posing as an outlaw on the run, and gain the wily outlaw’s confidence long enough to take him prisoner. But he would need some accomplices. He found them in two homesick gringo fugitives, Burt Alvord and Billy Stiles.

During the 1890s, one of Arizona’s most notorious outlaws, Augustine Chacon, terrorized citizens on both sides of the border. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

Alvord had been a constable, and Willcox was formerly a deputy to Cochise County sheriff John Slaughter. His major interests were poker, pool, guns and practical jokes before he decided to do some moonlighting on the side by robbing a train. Burt wasn’t the sharpest knife in the drawer so he figured he’d never be suspected of masterminding a heist or two. His gang of rascals included “Three-Finger Jack” Dunlap, “Bravo Juan” Yoas, Bill Downing and Billy Stiles.

The Alvord gang succeeded admirably on its first job, robbing the Southern Pacific near Cochise on September 11, 1899, and got away with some $3,000.

Burt Alvord was the dull-minded constable of Willcox who masterminded two train robberies in Cochise County. The second one put him behind bars. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

Local lawman Bert Grover, who would later serve in the rangers, suspected Alvord but didn’t have enough solid evidence to make an arrest.

Caught up in its success, the gang tried to rob another train, this time at the train station in Fairbank on February 15, 1900. The outlaws didn’t figure on former Texas Ranger Jeff Milton riding shotgun that day. When the smoke cleared, the outlaws rode away empty-handed. Bravo Juan had a load of buckshot in his rear, and Three-Finger Jack was mortally wounded. The outlaws abandoned Jack along the trail, and when the posse caught up, he gave a deathbed confession.

Alvord and his gang were locked up in the county jail in Tombstone. One of the bandits, Billy Stiles, offered to testify against his cohorts and was released from custody. A few days later, he broke into the jail and freed his friends. Alvord and his friends then high-tailed it for Sonora.

Two years later, Burt Mossman heard that Alvord and Stiles wanted to come home. In January 1902, he got word to the fugitives that if they would help him capture Chacon, they could share the reward money and he’d testify in court to their good character. He even went so far as to put Billy Stiles on the payroll as a ranger. Alvord’s wife was threatening to divorce him if he didn’t come home soon. That gave Mossman some added leverage.

Apparently, Colonel Kosterlitzky knew of Mossman’s plans to make the illegal capture of a Mexican citizen but had no plans to interfere as long as the ranger didn’t create a situation that would force him to get involved. He, too, wanted Chacon brought to justice.

Burt Mossman rode into Mexico in April 1902, posing as a fugitive. He learned Alvord was holed up west of the village of San Jose de Pima. Two days later, he met up with Alford at his hideout. The hilltop adobe house was a veritable fortress with loopholes, battle shutters on the doors and windows and a commanding view of the surrounding terrain. Inside one of the rooms, horses were saddled and ready to ride out at a moment’s notice.

Alvord spent some time thinking about Mossman’s offer. He missed his wife and wanted to go home but didn’t want to betray Chacon. Finally, he agreed to cooperate and set up Chacon so the ranger could make the capture. Mossman then rode north to await word from Alvord on where he could meet Chacon. Billy Stiles would be the messenger.

Several months later, in late August 1902, Billy Stiles brought word that he, Mossman and Alvord would meet Chacon at a spring sixteen miles south of the border on the first day of September. To entice Chacon out into the open, they offered to cut him in on a plan to steal some prize horses from a ranch a few miles north of the border in the San Rafael Valley.

Mossman and Stiles rode to the spring on September 1, but Alvord and Chacon failed to show. They rode back across the border to spend the night and then returned the next day. Around sunset the following day they met the two outlaws on the trail. Both were heavily armed. Along with his rifle and pistol, Chacon was packing a large knife. Despite assurances by Mossman, claiming that he, too, was a fugitive, the cagy bandit was suspicious. His hand was never far from the butt of his six-gun.

That night they made camp, and Mossman nervously waited out the sleepless hours, his coat pulled up, concealing his face. Beneath the coat, his pistol was trained on Chacon. The ever-vigilant Chacon never let his guard down either. He refused to let any of the men get behind him. To make matters worse, Mossman wasn’t sure he could trust either Alvord or Stiles not to betray him.

At daybreak, the men got up and started a fire. While Chacon was fixing breakfast, Alvord slipped next to Mossman and quietly said he’d done his part and was heading out. He also warned the ranger not to trust Billy Stiles. Then he told Chacon he was going for water and would return shortly. While the three men were eating, Chacon’s eyes narrowed and he wondered suspiciously what was taking Alvord so long to return.

After breakfast, Chacon reached in his pocket and took out some corn husk cigarettes and offered them to Stiles and Mossman. As they hunkered down around the fire having a smoke, Mossman saw his chance. He let his cigarette go out and then reached into the fire with his right hand, picked up a burning stick and relit his cigarette. As he reached out and tossed the stick back into the fire, Mossman’s hand slid past his holster. Quick as a flash, the ranger pulled his revolver and got the drop on the surprised bandit. He ordered Chacon to put his hands up. The outlaw cursed but did as he was told. Next, the ranger told Stiles to remove Chacon’s knife and gun belt. And to Billy’s surprise, told him to drop his gun belt also. He then ordered both men to step back while he gathered in the rifles and pistols. After ordering Stiles to handcuff Chacon, the trio mounted up and rode for the border.

Mossman decided to avoid Naco, fearing Chacon might have friends there. Instead, he headed across the San Pedro Valley about ten miles west. Stiles rode in front, leading Chacon’s horse, while Mossman covered them both from the rear with his Winchester. As they neared the border, Chacon began to balk. So Mossman unstrapped his riata and dropped a loop around his neck, warning that he would drag him across the border if necessary. The outlaw cursed again but caused no more trouble.

They arrived at Packard Station on the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad line just as the train to Benson was passing through. Mossman’s luck was holding. He flagged it down, and they made the final fifty miles to Benson riding the steel rails. At Benson, they were met by Graham County sheriff Jim Parks, who was most eager to take Chacon back to the jail at Solomonville he’d escaped from five years earlier and his long-awaited rendezvous with the hangman.

Word spread quickly of Mossman’s daring capture of the outlaw Chacon and caused a lot of excitement around territory. A few eyebrows were raised when it was pointed out that his ranger commission had expired four days before he captured Chacon and he’d arrested the bandit on foreign soil. The Mexican government expressed outrage at the flagrant violation of their sovereign soil. Mossman stayed around Arizona just long enough to keep his promise to Billy Stiles. After testifying for Billy, he boarded a train and headed for New York City, where he was greeted royally by a grateful Colonel Bill Greene. He spent the next few weeks far removed from the political rumpus he’d created in Arizona.

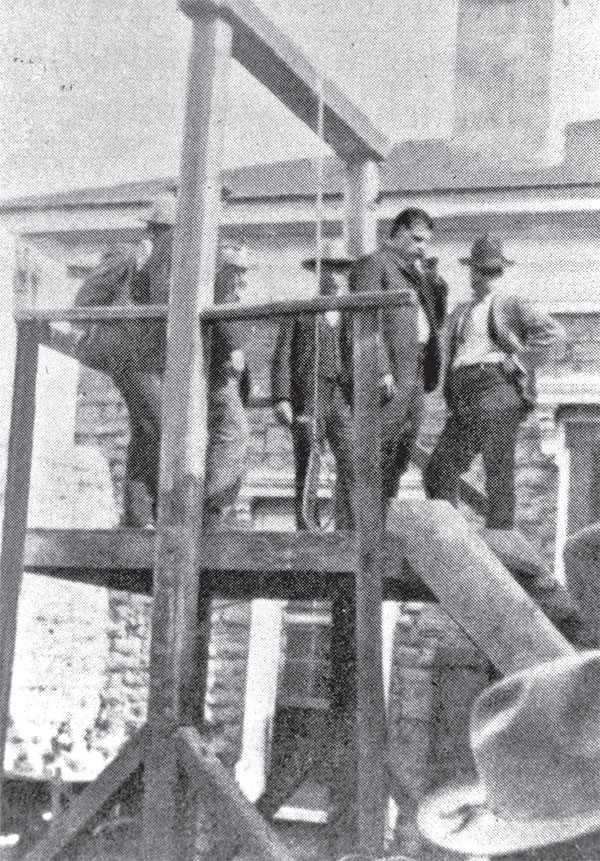

On November 23, 1902, Augustine Chacon was hanged in Solomonville, Arizona. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

At one o’clock on the afternoon of November 22, 1902, Augustine Chacon climbed the thirteen steps to the top of the scaffold and gave a thirty-minute speech that would have done a politician proud, closing with, “It’s too late now; time to hang…Adios todos amigos!”

Thus ended the career of one of Arizona’s most deadly and dangerous outlaws.

With the capture of Augustine Chacon, Burt Mossman closed out his brief career as a lawman in spectacular fashion. He went back to New Mexico, where he became a successful rancher. He died in Roswell, New Mexico, in 1956. A few years later, he was inducted into the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City. Chiseled out of old granite, Captain Mossman was one of the truly great cattlemen and lawmen of the Old West.