Master forger James Addison Reavis almost pulled off one of the biggest real estate frauds in American history during the 1880s. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

10

HUCKSTERS, HUSTLERS, SWINDLERS AND BAMBOOZLERS

The ways of a man with a maid may be wicked and strange. But simple and tame; when compared to a man with a mine when buying or selling the same!

—Bret Harte

The Arizona Territory proved to be an ideal place for swindlers and con artists to ply their trade. The wild, untamed country that lay between California and New Mexico bore a king’s ransom in gold and silver. However, it also proved to be fertile ground for silver-tongued swindlers. Million-dollar corporations were created on nonexistent mines in Arizona’s remote mountains, selling useless stock to eastern speculators. Land fraud also enriched these grifters, who proved over and over again that P.T. Barnum was right: “There’s a sucker born every minute.”

Today’s con artists selling lakeshore lots on the edges of mirages are mere amateurs when compared to those flimflam bamboozlers of yesteryear.

All good con artists have a few things in common: a gift of gab, charisma, no conscience and absolutely no shame.

The esteemed con man Dr. Richard Flower wasn’t really a doctor. He earned his living for a time selling cure-all bottled medicine. The label on Doc Flower’s medicine bottle claimed to cure, among other things, baldness, incontinence, impotency and unmentionable female disorders. It would turn fat into muscle and give a woman a full, rounded bosom. The concoction contained mostly alcohol, but few complained, especially those little old ladies who would never think of allowing whiskey to touch their lips.

Doc eventually grew tired of small-time schemes and decided to play for higher stakes. Fortunes were being made in the Arizona mines, and since he didn’t have a mine of his own, Doc decided to create one.

He’d never been to Arizona and wouldn’t have known a gold nugget from a kernel of cauliflower, but that didn’t stop him. He erected a phony movie set–looking mine complete with a head frame and shaft east of Globe near the little town of Geronimo. He bought a few samples of ore from a producing mine and headed back east to locate suckers…er, investors.

Doc returned to New York claiming to have discovered the richest gold mine in the history of the world. He decorated his New York office lavishly and began to sell stock in his “fabulous gold mine.” Flamboyant advertising and hard-sell sales pitches brought in suckers by the thousands. Soon, people were begging to buy stock at ten dollars a share. Then it went up to fifteen dollars a share. The rugged town of Geronimo became a household word throughout the eastern states.

He called his company the Spendazuma, a name that revealed Doc’s wry sense of humor. Mazuma was slang for money, so he was subtly asking his investors to “spend yer money.” Surprisingly, no one caught on. Soon, Doc Flower had suckers waiting in line to lay down their money in a nonexistent mine.

The balloon burst when a reporter named George Smalley from the Arizona Republican , today’s Republic , rode in to have a look at the Spendazuma Mine.

The reporter became suspicious when he looked at the prosperous-looking $10 million mine and took note that workers were as scarce as horseflies in December.

The property was being guarded by an irascible reprobate from Texas named Alkali Tom, who tried unsuccessfully to keep the pesky reporter from snooping around the imaginary gold mine, but Smalley was not to be denied. Barely escaping with his life, he made it to a telegraph station and posted his exposé.

When the story hit the newspapers, Doc’s lawyer indignantly threatened to sue for $100,000 and demanded a retraction. When that didn’t work, he changed strategies and offered Smalley a $5,000 bribe to rewrite the story and admit his mistake, causing the spunky reporter to chase the lawyer from his office.

Thus ended the Spendazuma Mine swindle, but Doc Flower wasn’t easily discouraged. Over the next few years, he was arrested several times for swindling, jumped bail, served some jail time and pulled off several other schemes, including bilking a rich New York widow out of $1 million. Police chased him all over North and South America before catching up with him in Canada in 1916.

The law never could keep the silver-tongued swindler out of circulation for long, but the Grim Reaper managed to accomplish the feat. He was out on bond again and contemplating another caper when he collapsed and died while sitting in a movie theater in Hoboken, New Jersey.

THE BARON OF ARIZONA

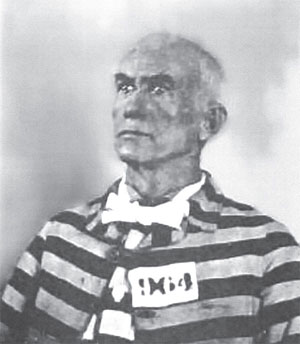

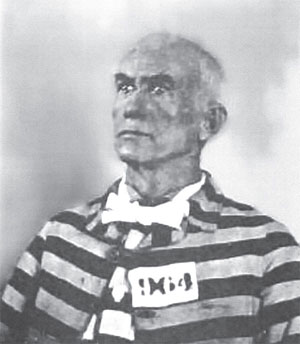

Back in the 1880s, a man from Missouri named James Addison Reavis nearly succeeded in pulling off one of the largest land swindles in history.

Reavis was born in Henry County, Missouri, in 1843. When the Civil War broke out, he joined a Confederate unit but soon got homesick and began writing his own military passes, even forging his commanding officer’s signature. Soon he was on leave more than he was on duty. Finally, he forged discharge papers and went home for good.

After the war, he found work in a real estate office in St. Louis, where he used his skill in forgery to earn money on some dubious land deals. Honing his skills, Reavis was soon ready for the big time.

Reavis invented a family lineage that began with a Don Nemecio Silva de Peralta de la Córdoba. The fictitious Peralta was given the title of Baron de los Colorados by King Ferdinand VI in 1748, along with a huge grant of land. To explain how he came into possession of the grant, Reavis claimed he acquired a title from a George Willing, a mine developer, who’d come to Arizona and purchased it from Miguel Peralta, a poverty-stricken descendant of the Baron. Willing had recorded the deed in Prescott in March 1874 and died the next day. Miguel Peralta was also a figment of Reavis’s fertile imagination.

Master forger James Addison Reavis almost pulled off one of the biggest real estate frauds in American history during the 1880s. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

The land Reavis claimed was nearly twelve million acres, running through the heart of Arizona. It extended from today’s Sun City across to Silver City, New Mexico, including rich mining properties.

The tall, rangy Missourian with the muttonchops beard also had an incredible gift of gab and was a natural born salesman and wheeler-dealer. His biggest coup was convincing the owners of the Southern Pacific Railroad and several large mine owners his land grant claim was legitimate.

Doña Sophia Micaela Maso Reavis y Peralta de la Córdoba, third baroness of Arizona. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

Reavis needed another connection to the Peralta family, and he found her in the person of a sixteen-year-old orphan girl whom he christened Doña Sophia Micaela Maso Reavis y Peralta de la Córdoba, third baroness of Arizona.

He convinced the youngster she was descended from the Peralta family and then married her. To a master forger it was a simple task to alter church records and make her the last surviving member of the illustrious but fictional Peraltas. He traveled to Mexico City and Guadalajara, spending hours in museums and archives inserting the fictional Peralta family into the archives. Later he went to Spain and did the same in Madrid and Seville.

Reavis experimented with various inks and paper, learning to match the ancient documents. He even bought some anonymous old portraits in a Spanish flea market and designated them as various members of the Peralta lineage.

Reavis didn’t plan to evict the occupants from his barony. All he wanted to do was extort enough in fees for rent and quitclaim deeds to support him and his wife in a courtly manner. The railroad gave him $50,000, and the Silver King mine paid $25,000. The large mine owners and railroad nabobs decided it was cheaper to pay the baron his fees rather than fight him and risk losing their valuable properties.

It was the small landowners who took umbrage and caused his undoing. At first they wanted to lynch the smooth-talking baron. The federal government at one point considered paying him millions to settle the claim. Famous lawyers Robert Ingersoll and Roscoe Conkling examined the documents and found them legitimate.

Reavis and Sofia traveled to Europe, where they were welcomed by Spanish aristocracy who were amused to see the baron tweak the nose of the despised yanquis . He maintained homes in Arizona; St. Louis; Washington, D.C.; Madrid; and Chihuahua City and spent much time traveling with his family. The cattle on his ranches were branded with “PR” and were quickly dubbed the “Swindle Bar Brand.”

Actor Vincent Price starred as the master forger in the 1950 film The Baron of Arizona. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

Everything was going well for the baron, but the wheels of justice were slowly turning to expose the fraud. Investigator Royal Johnson released his report in 1889 disclosing forgeries and historical inaccuracies. One said the calligraphy used in the documents was a recent design. Some parts of the documents were written in quill, while others were in steel pen. The steel pen didn’t come into use until the 1800s. Reavis indignantly sued the government for $11 million. He lost the case and was arrested for fraud as he left the courthouse.

In 1895, Reavis was brought to trial, found guilty and sentenced to two years in the penitentiary in Santa Fe and fined $5,000, proving once again that Americans love a creative con man who operates on a grand scale.

The Baron of Arizona was behind bars from July 18, 1896, until April 18, 1898. The baroness Sophia was living in Denver with their two children. He visited New York City; Washington, D.C.; and San Francisco seeking new investors to develop properties, including some irrigation projects in the Arizona’s Salt River Valley, but found no takers. He headed for Denver to live with the baroness, but they eventually separated and she divorced him in 1902 for nonsupport. He spent some time living in a poorhouse in California. He died in Denver on November 20, 1914, and was buried in a pauper’s grave.

Sophia died on April 5, 1934, going to her grave believing she was descended from a real baroness.

ANTHONY BLUM

Strange things happen in a courtroom, but it would be hard to top the time down in Cochise County when a shameless scoundrel named Anthony Blum bilked a local priest out of $5,000. Blum conned Father Arthur DeBruycher into investing in a “sure thing” gold mine in Gleeson, Arizona. When the mine didn’t pan out, the priest filed suit alleging fraud and misrepresentation.

For two years, Blum used a variety of tactics to delay the trial. After he’d exhausted all his excuses, the suit went to trial in Tombstone. Blum was on the stand getting ready to defend himself when suddenly he slumped forward clutching his chest.

His personal physician, who just happened to be in the courtroom, rushed forward, examined him and sadly announced there was no hope. Blum was a goner and would be dead within minutes.

As he lay dying, Blum pleaded for a priest to make his death confession and administer last rites. The only clergy close by on such short notice was the plaintiff, Father DeBruycher.

The court gave the priest permission to proceed hearing Blum’s confession and administer absolution. However, these actions placed the priest under the seal of the confession, and he could never reveal what Blum told him.

But wait! A miracle occurred. Apparently, Blum’s confession had cleared his conscience and his heart attack. He immediately regained his health. His doctor reexamined him and pronounced him fit to go home.

The trial was put on hold for another year, but since the priest could no longer testify and there were no other witnesses to the scheme, Blum was free to go. The priest was chastised by the Church for bad judgment, and he was out of pocket $5,000.

CYCLONE BILL

Cyclone Bill was a mischievous little shyster and a well-known character to the bartenders around Arizona. He’d studied law as a young man in Texas but didn’t practice long. He claimed his first client was a shiftless cowboy charged with stealing cows and assigned to him by the local court. “That cow thief took one look at me and said, ’Yer honor, I plead guilty.’” He went on to say, “So I quit practicing law and went to punching cows.”

Somewhere along the way, Cyclone had been shot in the leg, and the wound left him with one leg considerably shorter than the other. Depending on which leg he was standing on, Cyclone could be tall or short. Old-timers around Clifton tell about the time he bellied up to a crowded bar on Chase Street and, standing on his short leg, shouted, “Bartender, drinks for the house.”

Drinks were served all around, and while the bartender was distracted, he ducked into the group of imbibers and switched to his tall leg. When the bartender turned around to collect the tab, the short man was nowhere to be found. The red-faced bartender roared, “Where’s that little scalawag who ordered drinks for the house?” No one said a word.

During the famous Wham payroll robbery in Graham County in 1889, an eyewitness said one of the bandits limped, so Cyclone, being the “usual suspect,” was arrested. The resulting notoriety gave him his fifteen minutes of fame, and he milked it for all it was worth before producing an alibi.

His real name was William “Abe” Beck, but everyone called him Cyclone Bill. He claimed the nickname came after the railroad reached Yuma in 1877 and there was much money to be made hauling freight by mule team to Tucson. He was hired by a freight company to haul a load of goods from Yuma to the Old Pueblo.

Beck, the freight wagon and the mules never reached their destination. All had mysteriously vanished. A year later, he showed up in Tucson without the rig and was met by the owner, who demanded to know what happened to his goods, wagon and ten-mule team.

Bill claimed that somewhere between Tucson and Yuma a giant cyclone came roaring down and swallowed the mules, wagon and himself, whirling them high in the sky and plopping them back to earth somewhere in Kansas. He vaguely recalled the wild wind blowing him in an eastward direction, so he headed west for about a year until he arrived back to Tucson.

In court, Bill swore he had no idea what happened to the mules, wagon and freight and that he was lucky to get through it alive. The unsympathetic judge presented him with both a jail sentence and a nickname.

THE GREAT DIAMOND HOAX

Of all the schemes during the late nineteenth century, none was more bizarre than one perpetrated by a couple of cousins from Kentucky named Philip Arnold and John Slack.

Arnold and Slack, whose names conjure up thoughts of a vaudeville team, managed to acquire from a friend who worked for a diamond drill company a large number of flawed, industrial-quality or otherwise inexpensive gems of all kinds and began a quest to find a greedy but not-too-sharp investor. They figured California would be the best place to unleash their scheme.

Their “pigeon” was a prosperous San Francisco banker named George Roberts. With dramatic flair, they walked into his office one day in 1871 and emptied a sack of diamonds and other precious gems on his desk. After acquiring his undivided attention, the two hucksters proceeded to stage a great argument about whether they should share their secret and accept financing from outsiders.

Soon the skeptical banker was begging for the opportunity to provide money to develop the huge diamond field located “somewhere” in northeastern Arizona.

Although sworn to secrecy, Roberts shared the information with William C. Ralston, founder of the Bank of California. The two bankers couldn’t wait to invest in the venture.

Grubstaked with $50,000, Arnold and Slack left on another expedition and returned three months later looking disheveled, telling harrowing tales of Apache attacks. They were also toting a sack full of precious diamonds.

Ralston sent the gems to an eastern merchant, who pronounced them genuine. Of course they were genuine; Arnold and Slack had purchased them with some of the money the bankers had given them.

Tiffany’s of New York became interested in the gems and sent an engineer, Henry Janin, out to examine the diamond field. This presented a slight problem for the two promoters; they had to create a diamond field, so they found a remote mesa in northwestern Colorado and spread a large number of gems around.

Janin was one of the foremost mining engineers in the United States, and his presence should have given credibility to the scheme. However, he was a man with no experience with gemstones, otherwise he would have known that several varieties of precious stones rarely occur in the same place. The famed geologist would become an unwitting partner in the scheme. Tiffany’s appraised the diamonds at $150,000, a sum considerably higher than the $20,000 Arnold and Slack had purchased them for in England. It also gave them more money to purchase more uncut gems to lure the investors further into their bold scheme.

Thanks to Janin’s report, Tiffany’s of New York, the Rothschilds, the Bank of California, Horace Greeley, General George McClellan and General George Dodge all ponied up huge sums of money in the get-rich-quick scheme. A $10 million corporation was formed to exploit the field of precious gems.

The investors insisted they be taken to the site of the gem field, so in June 1872, the two con men took them by rail from St. Louis to Rawlins, Wyoming, and then led them on a circuitous four-day horseback journey into northern Colorado. Finally they came to the location where Arnold and Slack had “salted” the area with precious gems. The investors eagerly gathered in the “treasure.”

Arnold and Slack were paid $600,000 to relinquish future claims to the diamond field, and the two proceeded to leave immediately for other parts.

The Great Diamond Hoax was finally exposed when Clarence W. King of the U.S. Geological Survey became suspicious, located the salted mesa and wrote a withering exposé. He noted not only that rubies, emeralds, sapphires and diamonds are not found together in nature but also that none of the stones was recovered from natural surroundings. Most had originated in South Africa. The two con men had purchased cheap cast-off and refuse from jewelers in Amsterdam and London for the sum of $35,000.

King’s suspicions were said to have been first confirmed when he found a diamond with a jeweler’s facet already polished upon it.

William Ralston, head of the Bank of California; Henry Janin; Charles Tiffany; Baron von Rothschild; and the other investors became the butt of jokes around the world for being hornswoggled by a couple of “hillbillies” from Kentucky.

Philip Arnold returned to his home in Elizabethtown, Kentucky, and became a banker. Authorities eventually managed to find him, and he agreed to pay an undisclosed sum for the promise of immunity. In 1878, he became embroiled in a feud with a rival banker that turned violent and resulted in him being shot and seriously wounded. He died of pneumonia six months later at the age of forty-nine.

John Slack went to St. Louis, where he owned a casket-making company for a time, and then he moved to White Oaks, New Mexico, where he became an undertaker. They never caught up with Slack, and the matter was eventually dropped. Slack died in 1896 at the age of seventy-six.