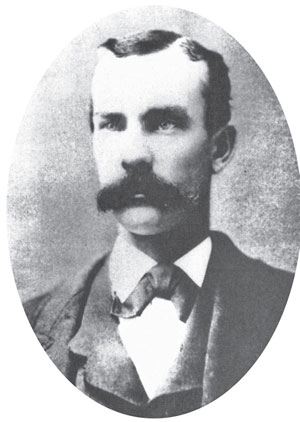

Johnny Ringo had a great name, but his skills as a gunfighter were highly overrated. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

11

BAD BOYS OF COCHISE COUNTY

JOHNNY RINGO

Having a catchy “gunfighter” name was almost a sure way to immortality. Writers and dime novelists have turned a few mediocre shooters into legends. Henry McCarty might never have become famous as “Henry the Kid.” Nor would James Butler Hickok have done as well with a name like “Wild Jimmy.” Arguably, the greatest gunfighter name of them all has to be Johnny Ringo. He might also have been the most overrated gunfighter of them all. He wasn’t the fastest or the best by any stretch. Writers described him as a man who had a vast collection of scholarly books and could quote Shakespeare at the drop of a hat. Author John Myers Myers wrote, “He attended college in a day when only men of good background did so.” Cochise County deputy sheriff Billy Breakenridge, teller of the tallest Tombstone tales of them all, claimed that he was an educated man with an extensive collection of books, classics, that he read in original Greek and Latin. Truth is, Ringo never even finished grade school, much less high school and college. He is more accurately defined in the title by one of his recent biographers, Jack Burrows, author of John Ringo, the Gunfighter Who Never Was .

The legend began to grow shortly after his body was found at Turkey Creek on July 14, 1882. Newspaper accounts of his reckless, erratic behavior inspired writers to create the myth of a gunfighter extraordinaire.

Johnny Ringo had a great name, but his skills as a gunfighter were highly overrated. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

The name Johnny Ringo certainly helped in this creation. Descriptions such as “fearless” and “King of the Cowboys” along with recollections of “old-timers” were later used by writers to forge his legendary image.

He was born on May 3, 1850, in Washington, Indiana. When he was six, the family moved to Missouri and eventually to California. By 1874, he was in Texas, where he became involved in the Mason County War (Hoodoo War) between German immigrants and native Texans. He was one of the feudists charged and convicted of murder, spending almost two years behind bars before the charges were dismissed. He arrived in Arizona in late 1879.

Ringo was an active participant in the feud between the Earps and the cowboys that culminated with the so-called Gunfight at the O.K. Corral on October 26, 1881. Ringo managed to be absent at that one, but he was suspected of participating in the cowardly shotgun ambush of Tombstone marshal Virgil Earp on December 28, 1881.

His body was found on July 14, 1882, by a wood hauler some twenty-four hours after he’d been shot in the head. In his hand was a pistol containing five cartridges. A cartridge belt was tied around his waist, upside down. A piece of his scalp was missing. His boots were missing, and his feet were wrapped with an undershirt. An inquest was held, and the body was buried. A coroner’s jury ruled it suicide. Wyatt Earp later claimed he’d come back to Arizona and killed Ringo. Others say Doc Holliday shot him. Billy Breakenridge blamed Buckskin Frank Leslie. As Billy Claiborne lay dying on Allen Street in Tombstone following a gunfight with Buckskin Frank, his last words were, “Frank Leslie shot John Ringo. I saw him do it.” Fred Dodge, undercover agent for Wells Fargo, said Mike O’Rourke, aka Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce, did the deed. Ringo’s pal Pony Diehl sought out Johnny and killed him. Was it murder or suicide? Most likely it was the latter, but historians still argue the matter. People love conspiracies, and this one’s a favorite.

After his death, Ringo would become the “classic cowboy-gunfighter.” He was described as a “strictly honorable man whose word was his bond.” Others called him “fearless in the extreme.” He was even called the “King of the Cowboys” and a real life Don Quixote. None of this is true. Stealing cows was his stock in trade. His only killing was in the Texas Hoodoo War, when, on September 25, 1875, he and a man named Bill Williams rode up to James Cheyney’s place. Cheyney was rumored to have set up a couple of their friends for murder. Cheyney invited the two men to have dinner and was washing his face. The unarmed man’s face was covered with a towel, and he didn’t see the two draw their pistols. All he heard were the gunshots that took his life.

In December 1879, soon after he arrived in Safford, Arizona, Ringo shot and wounded another unarmed man named Louis Hancock because the latter refused to have a drink with him. These appear to be the classic cowboy-gunfighter’s only gunfights.

JOE GEORGE , GRANT WHEELER AND THE FLYING PESOS TRAIN ROBBERY

One of Arizona’s zaniest train robberies took place five miles west of Willcox on January 30, 1895, when two cowboys named Joe George and Grant Wheeler decided to raise their station in life by robbing the Southern Pacific Railroad.

Since neither had ever heisted a train before, there was going to be a degree of “on-the-job training.” So the cowboys turned wannabe train robbers purchased a box of dynamite at a local business in Willcox under the pretense of going prospecting. They cached their blasting powder and hobbled their horses some seven miles west of town and then walked a couple of miles back to meet the train.

West of Willcox was a long grade that slowed the train enough that the two cowpunchers jumped on board with ease. It didn’t take much persuasion to entice the engineer to stop the train, especially when he was looking into the muzzle of a Colt .45 revolver.

One of the desperadoes jumped down, uncoupled the passenger cars and signaled the obliging engineer to pull forward with the mail and baggage cars to where the dynamite was stashed.

They broke into the express car and found the Wells Fargo messenger had slipped out the door and hightailed it back to the passenger cars.

Inside the express car were two safes, one a small fragile-looking lockbox and the other a large sturdy-looking Wells Fargo safe. Lying nearby on the floor were several sacks full of Mexican silver dollars, also known as “dobe dollars.” At the time they were about the same value as U.S. dollars.

Wheeler and George placed a few sticks of dynamite around the two safes, lit the fuses, jumped out the door and sprawled on the ground, arms covering their heads.

The first blast destroyed the door on the small safe, but the prize, the large Wells Fargo safe, remained intact so they tried again. This time they added a couple extra sticks for good measure. Once again they jumped out of the car and hit the dirt. When the smoke cleared the big safe reappeared, unblemished.

Finally the frustrated train robbers piled the rest of their blasting sticks around the safe and, for ballast, packed eight bags of Mexican silver dollars on top. They struck a match to the fuse and lit out for the nearest cover.

The resounding blast shook the ground from the Dragoons to Dos Cabezas. The entire express car was blown to splinters. Small pieces of lumber and one thousand silver pesos were flung far and wide. It was something of a miracle the two outlaws managed to survive the blast. The flying silver missiles that spewed from the exploding express car impregnated everything they hit, including the telegraph poles alongside the track.

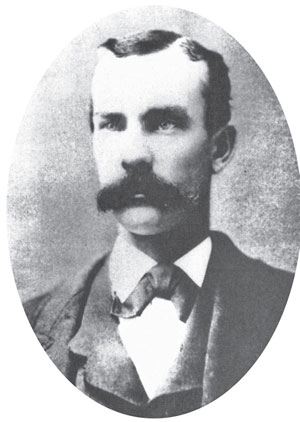

Train robber Grant Wheeler, along with partner Joe George, blew up a safe, scattering hundreds of pesos in the desert. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

When the smoke cleared, the two amateurs entered the car and found the durable safe door blown off but only a few dollars tucked inside. The real treasure in the express car was the Mexican silver pesos, and they were scattered all over the countryside. The discouraged pair stuffed a few battered coins in their pockets and rode off into the night.

When the train backed into town and sounded the alarm, rather than form a posse to go after the outlaws most of the citizens stampeded out to the scene of the crime to search for silver. It was said that for several years afterward folks were still raking the ground and looking for silver pesos.

It was probably the best manicured piece of desert landscape this side of the town of Paradise Valley, Arizona.

DON’T REACH FOR YOUR SIX -SHOOTER UNLESS YOU KNOW IT’S THERE

Bill Downing was one of the most disliked fellows in Old Arizona. He was moody, morose, bad-tempered, sullen and surly. And that was when he was sober. He got downright mean and ugly when he was drinking.

Bill was so unlikeable that even members of his gang could barely tolerate him. He was a member of the Burt Alvord gang in Cochise County and was arrested along with Alvord and Billy Stiles for holding up the train near Cochise. Stiles cut a deal with prosecutors to testify against his friends and was released. His proposal to rat on his friends was apparently a scheme because a few days later he walked into the jail in Tombstone, pulled a gun on the jailer and released Alvord and the others but left Downing locked in his cell. Downing spent the next few years cooling his heels in the infamous Yuma Territorial Prison.

After his release in 1907, he returned to Willcox and opened a saloon called the Free and Easy. It soon became a hangout for all the nefarious rascals in that part of Cochise County. That same year, the Arizona Territory had passed a law banning women from “loitering” in saloons, but that didn’t stop Bill. He employed an assortment of shady ladies to drink with the customers. He also trained them to be slick-fingered pickpockets, a trade he’d learned in prison.

Their victims were always reluctant to complain because of Bill’s reputation as a bad hombre. The law was champing at the bit to arrest him, but the folks around Willcox were so terrorized none would come forward and press charges.

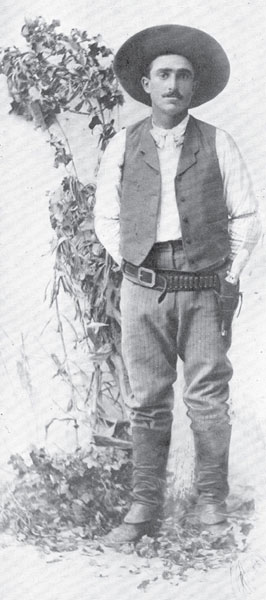

Bill Downing was a member of the Alvord gang that robbed the Southern Pacific Railroad on September 9, 1899, near Cochise Station. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

That changed when he beat up one of the girls, Cuco Leal, and she complained to the town marshal, who issued a warrant for his arrest.

The best time to serve a warrant to a bibulous reprobate like Bill was early in the morning while he was still groggy from the previous evening’s revelry.

Arizona Ranger Billy Speed just happened to be passing through Willcox, and Constable Bud Snow enlisted his help in making the arrest.

On the morning of August 5, 1908, the two lawmen stood in front of the Free and Easy Saloon and called on the old outlaw to step outside. He’d just bellied up to the bar demanding more of the “hair of the dog that bit him” from the night before and ignored the lawmen.

After Ranger Speed called a second time, Bill emptied his glass, turned and headed for the back door.

Like a lot of Old West showdowns, there is more than one version among old-timers as to what happened next. One said if it didn’t happen this way it coulda happened that way. Another said if it didn’t happen this way it shoulda happened that way. This one’s my favorite:

Let’s call it Cuco’s Revenge. Bill had done a good job teaching her the skills of picking some unsuspecting sucker’s pocket. That morning, she was standing next to him at the bar, and as he turned to leave, she reached around and removed the pistol from his holster. She was so slick he hadn’t realized it had gone missing. He headed out the back door and around the rear of the saloon intending to sneak up on the lawmen and get the drop on them.

Billy Speed anticipated his move and, armed with his .30-40 Winchester, headed in the same direction. The two turned the corner at the same time and faced each other in the classic Old West confrontation.

Bill reached for his pistol. The ranger, seeing the outlaw’s hand go toward his hip, raised his rifle and fired.

Much to Bill’s surprise and chagrin, his holster was empty. Cuco had had beaten him to the draw…a few moments before the fight.

A coroner’s verdict ruled the killing justified, and nobody mourned his passing.

He’d bullied those folks so many times they were just waiting for a chance to turn the tables on him.The incident was the inspiration for an old gunfighter axiom that still holds true: don’t reach for your six-shooter unless you know it’s there.

RUSSIAN BILL : AN OUTLAW IN THE WORST WAY

Dime novels of the nineteenth century romanticized outlaws of the Old West as noble, free-spirited rapscallions who robbed from the rich and gave to the poor. Common sense tells us the reason they didn’t steal from the poor was because there was nothing to steal, and they didn’t share their ill-gotten wealth with them either.

Dime novels were read voraciously not only by easterners but foreigners as well. These books even inspired a few wannabes to go west and become outlaws. For some, it was a bad business decision.

For example, one of Arizona’s most exotic outlaw wannabes was William Tattenbaum, a young Russian officer in the czar’s army. He eagerly devoured these lurid tales from afar and became so enamored of the outlaws of the Old West he deserted the army and came to America to become an outlaw.

He arrived in Tombstone, Arizona, in 1881, all decked out in new cowboy clothes. He’d even carved notches on the handle of his six-shooter to show he’d killed men in battle. When they asked his name, the young man answered in his best, tight-lipped cowboy dime-novel drawl, “They call me Russian Bill.”

Russian Bill was quite a novelty in Tombstone. Although he tried to act like an outlaw, he was much too refined to be taken seriously. The tall, handsome, curly-headed blond spoke several languages fluently and was quite intelligent. Quoting Greek and Latin, he charmed the shady ladies of Tombstone and Galeyville. Curly Bill and the other outlaws were amused and even let the Russian join their gang.

Still, Russian Bill felt like a phony. He was hanging out with some of the most disreputable outlaws in the West, yet he’d never committed a crime.

So to certify his claim, he rustled a few cows. It was the work of an amateur, and Bill was quickly captured and thrown into the pokey at Shakespeare, New Mexico. There he was reunited with a cohort from Tombstone named Sandy King.

The locals apparently hadn’t read the glorified accounts in dime novels of outlaws who robbed from the rich and gave to the poor. A vigilance committee convened and sentenced the two to hang, calling one an outlaw and the other a “damned nuisance.”

Bill and Sandy were placed on their horses and hanged from the beams of the dining hall of the Grant Hotel, which also served as the station for the transcontinental stagecoach line. The next morning when the stage arrived, the passengers disembarked and went in for breakfast. They were greeted by two dead outlaws dangling from the rafters. It’s no wonder easterners had such an adverse perception of the Wild and Wooly West.

An enduring legend along the Mexican border says that when Bill’s mother, the Countess Telfrin in Moscow, inquired as to the circumstances surrounding her son’s death, she was told he died of shortage of breath—while at a high altitude.

ZWING HUNT

According to Cochise County deputy sheriff Billy Breakenridge, Zwing Hunt was one of the worst outlaws in that hell-for-leather county. He came from Texas and was from a good family, but somewhere along the way he went bad. He arrived in Arizona with another hellion named Billy Grounds. For a spell, Hunt worked as a cowboy for the Chiricahua Cattle Company but soon turned to outlawry. He and Billy began by rustling cattle but got into more serious crime when they ambushed a party of Mexicans who were smuggling silver bullion and silver dollars out of Mexico. They killed everyone in the party and left them in what is known today as Skeleton Canyon. They buried the spoils somewhere in the canyon, and today it remains one of Arizona’s illustrious lost treasure stories.

Apparently, Zwing and Billy had some other escapades into Mexico. An alleged deathbed tale by Zwing claimed they rode out of Mexico following a three-month raid with two four-horse wagons loaded with plunder.

They hung out with a hell-raising crowd that included Johnny Ringo, Curly Bill Brocius, Tom and Frank McLaury and the Clanton brothers.

In the fall of 1881, some thirty head of cattle were stolen in the Sulphur Springs Valley, and the tracks led to a corral where they had been sold to a local butcher in the town of Charleston on the San Pedro River. The description of the rustlers matched that of Zwing Hunt and Billy Grounds. The pair escaped arrest by hightailing it into Mexico.

The following spring, two masked men with rifles entered the office of the Tombstone Mining Company and, without saying a word, shot and killed chief engineer M.R. Peel and then disappeared into the darkness. It was believed that they only planned to rob the company but one fired his weapon accidentally.

A few days later, word reached the sheriff’s office in Tombstone that the two suspects, Zwing Hunt and Billy Grounds, were holed up at the Chandler Ranch, some nine miles outside of town.

Sheriff John Behan was out with another posse at the time, so Deputy Billy Breakenridge had the responsibility of going after the bandits. He gathered a small posse of five men to join him, and they rode to the ranch, arriving just before daylight on the morning of March 29, 1882.

Breakenridge placed two possemen, Jack Young and John Gillespie, watching the back door of the ranch house while he and Hugh Allen guarded the front. Gillespie, aspiring to be a hero, walked up and pounded on the door, shouting, “It’s me, the sheriff.” The door opened, and Gillespie was shot dead. Another bullet shot Young through the thigh.

Then the front door opened, and a shot rang out, hitting Allen in the neck and knocking him to the ground. Breakenridge grabbed Allen by the shirt, dragged him to safety and then jumped behind a tree just as another shot hit nearby. Just then, the shooter, Billy Grounds, stepped into the doorway to fire another round. Breakenridge raised his shotgun and fired, hitting Billy in the face. The outlaw fell, mortally wounded.

In the meantime, Allen had regained consciousness and grabbed a rifle just as Zwing Hunt came around the side of the house. Both Breakenridge and Allen opened fire, hitting the outlaw in the chest. The battle had lasted only two minutes, and during that time, two men were killed and three wounded.

The dead and wounded were loaded up on a milk wagon and hauled into Tombstone.

Zwing Hunt, while recovering from his wounds, managed to escape with the help of his brother, Hugh, who came over from Texas. Hugh would later claim that Zwing was killed by Apaches, but others swore he escaped back to Texas, where, on his deathbed, he drew a map leading to the buried outlaw treasure. Folks are still looking for it, but so far it’s still out there somewhere.

BUCKSKIN FRANK LESLIE

Early Arizona was graced with a number of colorful characters with picturesquely whimsical names like Long-Necked Charlie Leisure, Shoot-Em-Up Dick, Long Hair Sprague, Red Jacket Almer, Lafayette Grime, Rattlesnake Bill, Johnny-Behind-the-Duece, Three-Finger Jack, Bravo Juan, Peg Leg Wilson and Jawbone Clark.

Along with those are a few lesser known, such as Coal Oil Georgie, Senator Few Clothes and Harelip Charley Smith.

Charming specimens of Eve’s flesh included Nellie the Pig, the Waddling Duck, the Dancing Heifer, the Galloping Cow, the Roaring Gimlet, Little Lost Chicken, Grasshopper, Madame Featherlegs, Peg Leg Annie, Dutch Jake, Nervous Jessie, Snake Hips Lulu and Lizzette-the-Flying Nymph.

Joining these pariahs of society was Nashville Frank Leslie, better known as Buckskin Frank Leslie. Buckskin was only five feet, seven inches tall and weighed 135 pounds. He was a handsome, dashing rogue and was also quite a ladies’ man. He had a hot temper and was prone to being violent when he was drinking. That would eventually be his undoing.

Frank’s early years were spent as an Indian scout for the army in Texas, Oklahoma, the Dakotas and later in Arizona. He arrived in Tombstone around 1880, where he easily slid into the raucous social life of Arizona’s largest boomtown. He was also good with a gun and was said to have killed fourteen men. He’s best known for his gunfight on the evening of November 14, 1882, with the self-anointed “Billy the Kid” Claiborne, a member of a loose-knit gang of cattle rustlers known as the Cowboys.

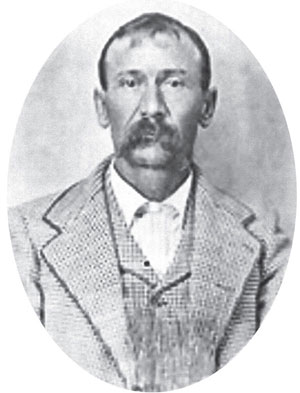

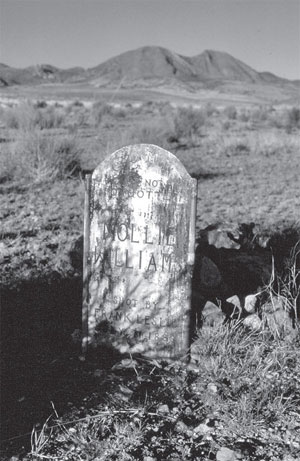

Buckskin Franklin Leslie had been an army scout, gambler, gunman and lawman. During a drunken, jealous rage, he shot and killed his lover, Mollie Williams. Courtesy of Southwest Studies Archives .

The real Billy the Kid was gunned down in the summer of 1881 by Lincoln County sheriff Pat Garrett, and Claiborne was now demanding folks apply that name to him. Locals, however, recalled that Claiborne had run away from the gunfight near the O.K. Corral leaving three of his pals to die. It was not the stuff of a real gunfighter, so Billy sought to repair his tarnished image by going around Tombstone with a chip on his shoulder.

That evening, Billy was drunk in the Oriental Saloon and made the mistake of insisting Buckskin Frank Leslie refer to him as Billy the Kid. Naturally, Leslie refused, something that enraged Claiborne. He got his hands on a Winchester and began telling everyone he was going to shoot Leslie on sight. When the buckskin man learned of the threat, he left the Oriental and met Billy in the street, where a gunfight ensued. Billy fired and missed. Frank fired and didn’t.

Among Leslie’s many amorous conquests was a married but separated lady named Mae Killeen. Her estranged husband, however, wasn’t willing to share his wife and threatened to shoot any man who made a pass at her. Leslie began escorting the dark-haired beauty around town, and when Killeen discovered the two sitting together on the veranda of the Cosmopolitan Hotel on the evening of June 22, 1880, he flew into a jealous rage. The two exchanged gunfire, and when the smoke cleared, Killeen would soon be pushing up daisies on boot hill. A week later, Leslie and the buxom widow were married. They split the blanket seven years later, allegedly after she grew tired of him making her stand against the wall while he traced her silhouette with bullets from his six-shooter.

Next, Leslie took up with a singer-prostitute named Mollie Williams (or Sawyer, or Bradshaw, or just plain Blonde Mollie). He may have killed her “benefactor,” a man named Bradshaw, and soon, the two were living together in what is best described as a stormy relationship. What Leslie and Mollie had most in common was their love of whiskey, and it led to many an argument. On July 10, 1889, at a ranch in the Swisshelm Mountains east of Tombstone, he killed her in a drunken fit of jealousy after accusing her of having an affair with a ranch hand known as “Six-Shooter” Jim Neil. Neil was a witness to the shooting, and afterward Leslie turned and shot him too. Leslie thought he’d killed Neil, but the youngster lived to testify against Frank for the murder of Mollie. The law finally caught up with Frank, and he was sentenced to twenty-five years in the Yuma Territorial Prison.

Frank was pardoned and released in November 1896, thanks in part to a wealthy widow named Belle Stowell. She’d fallen in love with the famous gunfighter while he was behind bars and began corresponding with him. They became husband and wife less than a month after his release. Somewhere along the way, they parted company, and he married Elnora Cast. History doesn’t record whether or not he ever bothered with divorcing any of her predecessors.

The body of Mollie Williams was laid to rest in a lonely spot in the Swisshelm Mountains of Cochise County. Author’s collection .

He seems to have disappeared around 1922, and his death is still disputed. One source says he committed suicide in 1925, while another says he struck it rich in the Klondike and died that way in the San Joaquin Valley.

The best information indicates his last years, drunk and penniless, were spent working as a swamper in a San Francisco pool, dying in 1930 at the age of about eighty.

The circumstances concerning Buckskin Frank’s death remain shrouded in mystery.

CURLY BILL BROCIUS : OUTLAW KING OF GALEYVILLE

His true name remains a mystery. Some accounts say it was William Brocius Graham, while others claim it was William Brocius or William Graham, but in outlaw lore, he was known as Curly Bill Brocius. Little of his past can be substantiated. Curly Bill left no letters or provided any information on his life before coming to Arizona, where he drifted after working as a cowhand in Texas and then in New Mexico. Supposedly he acquired his colorful nickname from a Mexican cantina girl who was enthralled with his dark, curly hair, but even that has been disputed.

Cochise County deputy sheriff Billy Breakenridge described him as being “fully six feet tall, with black curly hair, freckled face and well built.” No documented photos have been found, and there are no details regarding his mother and father. In short, he was a mysterious man from nowhere.

Curly Bill figured prominently in the outlawry along the Mexican border in the early 1880s. He was personally responsible for rustling thousands of Mexican longhorns and earned the dubious distinction of having his name mentioned in a number of hotly worded diplomatic notes exchanged between the United States and Mexico.

Like many notorious Wild West figures, Curly Bill had an inflated reputation as a gunslinger. However, the outlaws of Cochise County were a tough breed, and the fact that Curly Bill was a leader says something about respect. He hung out in Galeyville, a small community on the east side of the Chiricahua Mountains, where he was known as the “Outlaw King of Galeyville.”

His notorious Arizona reputation began sometime around midnight on October 28, 1880. Curly Bill was on a wild binge in Tombstone. He stepped out in the street, pulled his six-gun and started shooting holes in the sky. Town marshal Fred White attempted to disarm the drunken cowboy, but when Curly Bill surrendered his pistol, it went off and Marshal White fell, mortally wounded. Did Curly Bill murder White, or was it an accident? Whichever it was, henceforth it became known as the “Curly Bill Spin.”

Wyatt Earp was standing nearby when it happened. He whacked Bill upside the head with the barrel of his pistol, knocking him senseless, and then hauled him off to jail. Fearing a mob would lynch him, Wyatt took him to Tucson, where Bill spent some time in the Tucson jail before being acquitted by a jury packed with his cowboy pals. He was released from jail on December 27. Before White died, he exonerated Curly Bill by saying the shooting was an accident, and that’s all that saved the outlaw king from a hangman’s noose. During his trial, Judge Joe Neugass called the killing “homicide by misadventure.”

Fresh out of jail, Bill went on a rampage, terrorizing the towns and tormenting the citizens of Charleston, Contention City and Watervale along the San Pedro River. Bill was known around Arizona as an impulsive devil-may-care cowboy known to go on a tear at the drop of a hat. Newspapers referred to him as the terror of Cochise County. One wrote, “His playful exhibition of his skill with a pistol never failed to delight those communities which the peripatetic William favored with his presence.”

On January 8, 1881, Bill and another cowboy invited themselves to a Mexican fandango. One blocked the front door, while the other took the back. They pulled their pistols, yelled for the music to stop and ordered everyone to strip naked. Then he ordered the band to strike up the music and the dancers to dance for their amusement.

The following day, the two cowboys went into a church at Contention and interrupted the sermon by telling the reverend to quit preaching or he’d shoot his eye out. Then, warning him to stand perfectly still, the boys took turns shooting close to his head. They then aimed their pistols at his feet and made him dance a jig.

The boys then headed for Tombstone, where they got good and drunk and then rode down Allen Street “shooting holes in the sky.”

Nine days later, they rode into Contention City, robbed a till of fifty dollars and fired off a round at a citizen. After spending a day terrorizing the locals they rode on to nearby Watervale. From there Bill dared authorities to “come and get me.”

Bill’s shenanigans drew national publicity and made him the most famous outlaw in wild and wooly Arizona.

Bill didn’t limit his antics to Arizona, though. One night in Silver City, he burned down a saloon after he shot out a lamp, causing it to explode. Another time he shot a hole in a freighter’s hat for his own amusement. He also shot a hole in the hat belonging to a reporter who wrote a story the gunman didn’t appreciate.

At Fort Bowie, after telling a soldier to hold up a coin, Bill commenced to fire and knock it from between his fingers. Bill decided to try again, but this time he shot off the soldier’s thumb. Bill’s response to that was, “Looks like I’ve just gotten you a discharge from the army.”

One time in Galeyville, a saloonkeeper was getting ready to take a drink from a tin cup when Curly Bill shot it out of his hand. Unfortunately, the bullet went through the wooden wall and killed Bill’s horse.

Another time in Galeyville, he went into a restaurant, ordered a meal and then placed a six-shooter on each side of his plate and ordered everyone to wait until he was through eating before they could leave. When he finished, Curly Bill laid his head down on his arms and fell asleep. Although he was snoring loudly, everyone was still afraid to move. Sometime later he awoke, paid for everyone’s meal and left.

The so-called outlaw chief even assisted Deputy Breakenridge with collecting taxes, taking him into the lair of the cattle thieves, cajoling his pals to be “good citizens” and divvy up. Considering Breakenridge’s reputation for coloring up a story, this might be another one of his tall tales.

Galeyville was a rough town that had more than its share of outlaws and hard cases. Rough men and rough humor often led to bloodshed, even among their own. On May 19, 1881, Bill got into an altercation there with a cowboy from New Mexico named Jim Wallace. When Curly Bill stepped out of a saloon, Wallace bushwhacked him. The bullet struck Curly Bill in the cheek, went through and came out the other side of his mouth, taking some teeth. It looked for a while like the outlaw king was going to die, and his friends made plans to string up Wallace. But Curly Bill had a strong constitution, and he survived, although he did have to spend the next few weeks with an awkward bandage wrapped around his head.

Curly Bill wasn’t present at the so-called Gunfight at the O.K. Corral on October 26, 1881. No one seems to know for sure where both he and Johnny Ringo were that fateful day, but had they been present, the classic gunfight might have ended differently; if for no other reason, they would have provided more firepower.

During the months following the street fight in Tombstone, the Cowboys resorted to ambushing their enemies. On the evening of December 28, 1881, Virgil Earp was shot from ambush while patrolling the streets of Tombstone. Then, a few weeks later, on March 18, 1882, Morgan Earp was gunned down by an assassin.

The next day, the coroner’s jury included Curly Bill among seven suspected assassins. But once again, friends of the suspects provided alibis for them, and they were all released, proving once more that a cowboy couldn’t be convicted in Cochise County. Wyatt knew the only way justice would be served for the shooting of his brothers would be for him to take the law into his own hands. He would be his brothers’ avenger, becoming judge, jury and executioner. Wyatt led a small posse of friends on a vendetta against the perpetrators.

On March 21 at Iron Springs, in the Whetstone Mountains west of Tombstone, Wyatt and Curly Bill met again. There was a furious exchange of gunfire, and when the smoke cleared, Curly Bill lay dead on the ground.

Bill’s friends denied their leader died at the hands of Wyatt Earp. Some said he went to Mexico, married a pretty señorita and produced a bunch of kids; others said he went to Colorado and got a new start; still others said he went back to Texas.

Did Wyatt kill Curly Bill? Truth is, nobody was ever able to prove he didn’t. The Tombstone Epitaph , the newspaper supporting the Earps, ran a story agreeing with Wyatt’s version, and the Cowboy organ, the Nugget , sided with the Cowboys. They claimed he’d been miles away and offered a $1,000 reward to anyone who could produce Curly Bill’s dead carcass. In response, the Epitaph offered a $2,000 reward to anyone who could produce a live Curly Bill. Surely Curly Bill himself couldn’t have resisted an offer like that. One thing is certain: no one ever saw or heard from him again.