Liberal education entered the twentieth century under a cloud of criticism, much as it would exit. “[T]he American college is on trial. Condemnation is heard on every hand,” lamented the reforming president of Reed College William T. Foster in his extensive, 1911 study of the liberal arts curriculum, appearing in selection #52. Above all, critics targeted the prevailing disagreement, confusion, and uncertainty about the nature of liberal education. “The college is without clear-cut notions of what a liberal education should be,” observed the president of Cornell University in 1907, “this is not a local or special disability, but a paralysis affecting every college of Arts in America.”1 In 1918 the U.S. Commissioner of Education observed, “Within the last 25 years the curricula of colleges of arts and sciences have undergone large transformations. . . . There is disagreement among college officers as to the present aim of the college of arts and sciences. There is consequently disagreement as to the principles which should govern the framing of collegiate curricula.”2 The continuing problem was identified by Abraham Flexner in 1930: “No sound or consistent philosophy, thesis, or principle lies beneath the American university of today.”3

Both the cause and the effect of the conceptual problem lay in “the breakdown of prescribed programs through the evolution of the elective system.”4 One study of 105 liberal arts colleges found that the average number of elective credits grew from 16 percent of the total required for the B.A. degree in 1890 to 66 percent in 1940.5 To be sure, some celebrated this development. In 1907 Louis F. Snow interpreted the history of the liberal arts curriculum in the United States as an evolution toward greater freedom and electivism for the student, and this interpretation reached an apotheosis in the 1939 treatment of R. Freeman Butts, who attributed the development to the rise of Progressive education.6 But most college leaders affirmed with Amherst College President Alexander Meiklejohn “that a thing is understood only so far as it is unified. . . . In so far as modern education has become a thing of shreds and patches, has become a thing of departments, groups, and interests and problems and subjects, . . . our modern teaching, our modern curriculum, is not a thing of intelligent insight.”7

The chief mechanism for attempting to bring order to the curriculum was “systems of major and minor groups—devices for enforcing concentration and distribution of studies.” In the words of W. T. Foster below, “the most conspicuous of all the plans for compulsory concentration and distribution of studies is that which went into effect with the class of 1914 at Harvard College. After more than forty years of consistent, acknowledged leadership as the modern champion of the elective system . . . Harvard College took what some believers in President Eliot’s educational philosophy regard as a retroactive step. President [Abbott L.] Lowell secured the adoption of rules requiring of all students some degree both of scattering and of specialization in the choice of courses for the A.B. degree. . . .” By 1932 the dean of the college at the University of Chicago observed, “In the last decade a basic theory of college education has been put before us with increasing forcefulness: though a student who enters college with a well-defined educational aim should be given opportunity and encouragement to pursue that aim from the beginning of his freshman year, the major emphasis in the junior college years should be placed upon the breadth of educational experience; and, though general education should continue in senior college, the major emphasis of the last two years should be upon concentration in . . . some particular field of thought.”8

The concentration-distribution scheme did not, however, remedy the anomie, because the distribution requirements basically constituted an elective system with constraints. In response, proposals for “general education” began to arise in the 1920s as a means to organize the part of liberal education that was not in the concentration. Selections #53 and #54 by Lionel Trilling and Daniel Bell recount Columbia University’s pioneering effort at general education, while selection #55 by Stanford University professor Edgar E. Robinson portrays the concomitant invention of the orientation or survey course. By 1940 the general education movement had thus become a “groundswell . . . in the United States.”9

The consensus upon general education often disguised disagreement because a variety of meanings and interpretations marched under the banner of general education. Within the disputed territory known as “liberal education,” the attempt to identify a coherent domain named “general education” foundered on ambiguities among three primary interpretations: education for people in general, education for life in general, and high-minded general culture.10 The ambiguities resulted, in part, from the widespread experimentation in liberal education that occurred during the 1920s and 1930s, leading some to conclude that “the only [curricular] trend that can be clearly discerned is toward experimentation.”11 In the 1930s the American Association of University Women conducted an extensive study of this phenomenon, which is summarized in selection #56 by the study’s director, Kathryn McHale. There were many vectors in this experimentation; but the two major, intellectual themes were “Deweyan Progressivism” and “great books,” which exercised a powerful influence on the rest of liberal education due to the strength of their conviction and the cogency of their rationales.12 The Progressive effort is exemplified by selection #57 from the report of the Rollins College Conference on “The Curriculum for the Liberal Arts College,” chaired by John Dewey in 1931. The neo-Thomist or neo-scholastic variant of the Great Books movement is expressed in selection #58 by the well-known president of the University of Chicago, Robert M. Hutchins.

Born and raised in Boston, William T. Foster (1879–1950) and his family were left destitute after his father died early in William’s childhood. But he worked his way through Harvard College, graduating magna cum laude in 1901, and began teaching at Bates College in Maine. Two years later he returned to Harvard, earned an M.A. in English in 1904, and began teaching rhetoric at Bowdoin College, achieving promotion to full professor in 1905 after organizing a department of education in the college. Intrigued by the scholarly study of education (which he defends in selection #52), Foster moved to Teachers College, Columbia University, as a lecturer in 1909 and received the Ph.D. in 1911. His doctoral dissertation, “Administration of the College Curriculum,” incorporated the most extensive review of data about the topic to that point, including a study of “100,000 college grades, covering the total experience of 4,311 college students under the elective system at Harvard College for fifteen years,” as well as descriptions of the curriculum at two hundred colleges.13

In 1910 this informative study led to Foster being named the first president of Reed College, located in Portland, Oregon. Foster’s mission at Reed was “to establish a college in which intellectual enthusiasm should be dominant.” In his view, “if the life of the student was to be one of ‘persistent and serious study,’ there had to be an ‘uncompromising elimination’ of the activities that compete with studies—above all, of ‘intercollegiate games and fraternities and sororities.’ ”14 Foster’s realization of this vision was, however, compromised over the ensuing decade by the declining value of the endowment, disagreement over the academic program, and disapproval of his pacifism during World War I. In 1919 Foster resigned the presidency of Reed and commenced a new career as an economist, influencing fiscal policy in the administrations of Presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Foster died in 1950; his ashes were scattered over the lake on the campus of Reed College.

In the following reading, Foster’s tables of data about the liberal arts curriculum are supplemented by data drawn from two contemporary and complementary sources. The College-Bred Negro American was published by W. E. B. Du Bois and Augustus Granville Dill as Foster was completing his dissertation and assuming the presidency of Reed College. Dill studied with Du Bois at Atlanta University, graduated in 1906, and then earned another B.A. from Harvard in 1908. Returning to Atlanta University, Dill earned an M.A. in sociology and became Du Bois’s colleague.15 The second source was The Curriculum of the Woman’s College, which was published by the U.S. Bureau of Education in 1918 and authored by Mabel L. Robinson, who worked as a researcher at the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching after earning a Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1915.16

The present age is one of transition in higher education: the American college is on trial. Condemnation is heard on every hand. The capital charge is preferred that there is a general demoralization of college standards, expressing the fact that, as the college serves no particular educational purpose, it is immaterial whether the student takes the thing seriously or not. The college is said to retain traces of its English origin in the familiar twaddle about the college as a sort of gentleman factory—a gentleman being a youth free from the suspicion of thoroughness or definite purpose. The college is charged with failure in pedagogical insight at each of the critical junctures of the boy’s education, so that a degree may be won with little or no systematic exertion, and as a result our college students are said to emerge flighty, superficial, and immature, lacking, as a class, concentration, seriousness, and thoroughness. . . .

This confusion of ideas as to what should constitute the course of study for the Arts degree is revealed in the contradictory charges brought against the American college of today. . . . Some critics condemn the college for keeping its curriculum out of touch with the masses, and thus harboring an indolent aristocracy; others condemn the college for yielding weakly to the popular cry for more practical courses. Some deplore the desertion of culture courses in favor of courses of vocational trend; while others call the culture courses nothing but soft, wishy-washy excuses for sloth, indifference, neglect, and ill-concealed ridicule of the study and its teacher. Some critics hold that the one thing necessary is to secure concentration of each student’s work in some department, while others enact complicated rules to enforce the scattering of electives among various departments. . . .

One might present an endless confusion of opinions as to what the college course should be; but altogether they would demonstrate finally only one important truth, namely, that nobody knows what the American college course should be. It is needless to tarry long with individual opinions on this subject. The resultants of thousands of such opinions can be seen at a glance in tables showing the present requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American colleges. . . .

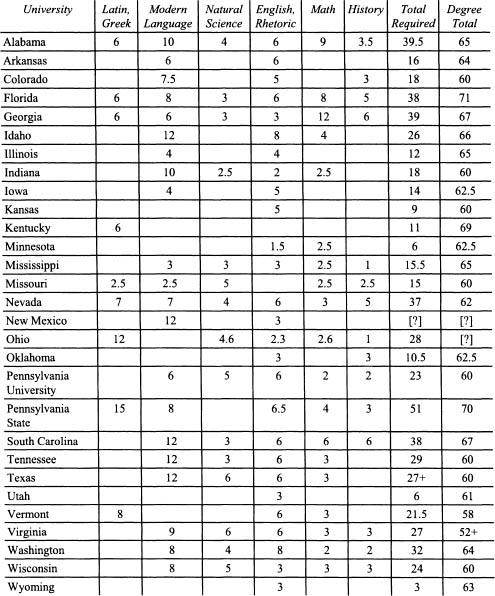

The following table indicates the subjects required for the A.B. degree in 29 state universities. The unit used is the year-hour: one hour per week for one academic year.

The most striking fact exhibited by the table is the total want of accepted ideas as to what subjects should be required for the A.B. degree or what proportion of the studies should be prescribed. A mere glance at the table shows the wide diversity of practice which has resulted from these attempts of many groups of men in many states to decide what is the essential core of a liberal education. Indeed, so great is the diversity of these requirements that if any one of these institutions is exactly right, all the rest must be wrong. The amount of required work ranges from three hours in Wyoming to thirty-nine and one-half hours in Alabama.18 There is no conspicuous central tendency, and the average deviation of the individual institutions is great. . . .

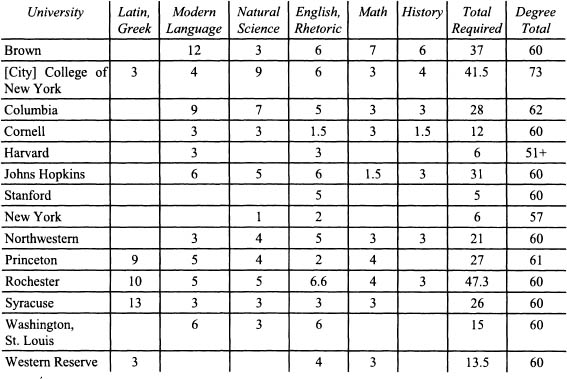

The following table presents the subjects required for the A.B. degree and the number of year-hours allotted to each in certain universities under private control. The variation here exhibited is even greater than that for state universities. Here again the curriculum appears to be administered in the familiar, historical way, not according to any clearly defined and abiding principle, but according to personal [considerations] of the moment and the place.

The following table indicates also the subjects prescribed in certain colleges for women [and for African-Americans], the most nearly uniform groups it is possible to find.19

The following table presents the practice of small colleges in all parts of the country. It would seem that the almost innumerable differences here revealed must shake the confidence of any faculty in the wisdom of its absolute prescriptions, and yet the table excludes those colleges exhibiting the greatest idiosyncrasies in their requirements. . . .

College catalogs from all parts of the country tell us that “students are required to pursue those subjects that are universally regarded as essential to a liberal education.” It would be pertinent to ask the writers of such statements to examine [these] tables and then name those subjects that are universally regarded as essential to a liberal education. Is there one? Even the general prescription of English is an agreement in name only; what actually goes on under this name is so diverse as to show that we have not yet discovered an “essential” course in English. And this is our nearest approach to agreement.

In most institutions the old compulsory programs of study have broken down of their own weight. Although, as the tables clearly show, nearly all colleges retain some vestige of the prescribed regime, yet in recent years most of the attempts to regulate the courses of study of individual students have dealt with systems of major and minor groups—devices for enforcing concentration and distribution of studies. Various practices of this kind we shall now consider in some detail. . . .

Various attempts to regulate the electives of college students are summarized, as far as it is possible to summarize such diverse practices, in the following tables. . . .20 The investigation covered two hundred of the better known colleges and universities. . . . Even these groups of colleges and universities, selected for the relative simplicity of their requirements, present great diversity and complexity as their most striking features. In the number of subjects required, in the number of year-hours unrestricted, in the proportion of work called for by the major subject, in the proportion controlled by the major adviser, in the amount prescribed for distribution, in the maximum and minimum allowances for groups, there is no uniformity, nor even any significant central tendencies.

Here, as in the attempts to prescribe “essential” subjects, the actual practices of colleges all over the country reveal no guiding principles. Most of these institutions force all students to do in general what their patchwork curriculum of a generation ago allowed no students to do. So innocent of abiding cause are these miscellaneous and contradictory regulations that the tables will be out of date, no doubt, shortly after they are printed. Indeed, such administrators as actually enforce these rules must be hard put to it for reasons, unless their students are uncommonly docile. One even wonders whether college officers can in all cases interpret their own rules. . . .

The statistics of actual student programs from various institutions . . . warrant the [conclusion] that not half of the concentration requirements in American colleges have more than a negligible effect. If compulsory specialization is preferable to complete election, then the proportion of a student’s entire work required in his major subject should be more than one-fifth. Less than that is no compulsion at all, only a pretense at “safeguarding” the elective system. . . .

The American college is on trial. . . . Yet, every year sees a larger enrollment. The total increase in seventeen years was over 150 percent, an increase out of all proportion to the corresponding gains in population. From 1902 to 1905 the registration of the small colleges in New England increased over twenty percent; and the rate continues until the question is, how much longer shall we have small colleges? Here, then, are the American public staking their sons, their daughters and their millions on their faith in the possibilities of the college, and yet agreeing, on the whole, with the verdict of the Nation that “the college is the least satisfactory part of our educational system and has urgent need to justify itself.” This seems an anomalous condition—our colleges growing rapidly both in numbers and in popular disapproval.21