CHAPTER ONE

Varieties of Intelligence

By intelligence the psychologist [means] inborn, all-around intellectual ability…inherited, not due to teaching or training…uninfluenced by industry or zeal.

—Sir Cyril Burt and colleagues (1934)

I BEGAN HAVING TROUBLE with arithmetic in the fifth grade, after I missed school for a week just when my class took up fractions. For the rest of elementary school I never quite recovered from that setback. My parents were sympathetic, telling me that people in our family had never been very good at math. They viewed math skills as something that you either had or not, for reasons having mostly to do with heredity.

My parents probably were not aware of the psychological literature on the question of intelligence, but they were in tune with it. Many if not most experts on intelligence in the late twentieth-century believed that intelligence and academic talent are substantially under genetic control—they are wired in and more or less unfold in any reasonably normal environment. Such experts were suspicious about the likely success of any effort to improve intelligence and were not surprised when interventions such as early childhood education failed to have a lasting effect. They were quite dubious that people could become smarter as the result of improvements in education or of changes in society.

But the results of recent research in psychology, genetics, and neuroscience, along with current studies on the effectiveness of educational interventions, have overturned the strong hereditarian position on intelligence. It is now clear that intelligence is highly modifiable by the environment. Without formal education a person is simply not going to be very bright—whether we measure intelligence by IQ tests or any other metric. And whether a particular person’s IQ—and academic achievement and occupational success—is going to be high or low very much depends on environmental factors that have nothing to do with genes.

There are three important principles of this new environmentalism:

- Interventions of the right kind, including in schools, can make people smarter. And certainly schools can be made much better than they are now.

- Society is making ever greater demands on intelligence, and cultural and educational environments have been changing in such a way as to make the population as a whole smarter—and smart in different ways than in the past.

- It is possible to reduce the IQ and academic achievement gap that separates people of lower economic status from those of higher economic status, as well as the gap between the white population and some minority groups.

The basic message of this book is a simple one about the power of the environment to influence intelligence potential, and more specifically about the role that schools and cultures play in affecting the environment. The accumulated evidence of research, much of it quite recent, provides good reason for being far more optimistic about the possibilities of actually improving the intelligence of individuals, groups, and society as a whole, than was thought by most experts even a few years ago.

On the other hand, just as there are laypeople and experts who are wrongly convinced that intelligence is mostly a matter of genes, there are laypeople and experts who have mistaken and sometimes overly optimistic ideas about the sorts of things that can improve intelligence and academic performance. One of the goals of this book is to present evidence on which interventions are most effective.

The chapters that follow emphasize that societal and cultural differences among groups have a big impact on intelligence and academic achievement. People of lower socioeconomic status have lower average IQs and achievement for reasons that are partly environmental—and some of the environmental factors are cultural in nature. Blacks and other ethnic groups have lower IQs and achievement for reasons that are entirely environmental. Most of the environmental factors relate to historical disadvantages but some have to do with social practices that can be changed.

Culture can also confer advantages for the development of intelligence and academic achievement. Some cultural groups have distinct intellectual advantages, on average, over the mainstream white population. These include people with East Asian origins and Ashkenazi Jews. Later, I discuss what these advantages are due to and whether some of them might be adopted by others who would like to increase their own intelligence and academic achievement.

Finally, I present ways of improving intelligence as suggested by new scientific findings.

Nearly everything in this book is readily understood without any particular technical knowledge. But it might be helpful to be familiar with statistics, so I provide an appendix defining some terms. Readers who want to brush up on their statistics might also want to look at the appendix. The concepts discussed there are normal distribution, standard deviation, statistical significance, effect size (in standard deviation terms), correlation coefficient, self-selection, and multiple-regression analysis.

Note that I have a somewhat atypical aversion to multiple-regression analysis, in which a number of variables are measured and their association with some dependent variable is examined. Such analyses can give a false impression of the degree to which causality can be inferred, and I refer to them only rarely and always with skepticism. Those of you who would like to see the basis of my prejudice can look at the part of Appendix A that deals with it.

To get us started, in this chapter I define intelligence, discuss how it is measured, present evidence on the two different kinds of analytic intelligence assessed by IQ tests, and discuss the types of intelligence not measured by IQ tests. I also examine how well IQ predicts academic achievement and occupational success, the types of intelligence not tapped by IQ, and important aspects of motivation and character.

Defining and Measuring Intelligence

A definition of intelligence by Linda Gottfredson is a good place to start:

[Intelligence is] a very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly and learn from experience. It is not merely book learning, a narrow academic skill, or test-taking smarts. Rather it reflects a broader and deeper capability for comprehending our surroundings—“catching on,” “making sense” of things, or “figuring out” what to do.

Experts in the field of intelligence agree virtually unanimously that intelligence includes abstract reasoning, problem-solving ability, and capacity to acquire knowledge. A substantial majority of experts also believe that memory and mental speed are part of intelligence, and a bare majority include in their definition general knowledge and creativity as well.

These definitions leave out some aspects of intelligence that people in other cultures would be likely to include. Developmental psychologist Robert Sternberg has studied what laypeople in a large number of cultures think should be counted as intelligence. He finds that a good many people include social characteristics, such as ability to understand and empathize with other people, as aspects of intelligence. This is especially true of East Asian and African cultures. In addition, East Asian understanding of intelligence emphasizes the pragmatic, utilitarian aspects more than Western views do, which are more likely to value the search for knowledge for its own sake, whether or not it has any obvious immediate uses.

Intelligence is often measured by IQ tests. The Q, by the way, stands for quotient. The original IQ tests, which were devised for schoolchildren, defined intelligence as mental age divided by chronological age. By that definition, a ten-year-old with a test performance characteristic of twelve-year-olds would have an IQ of 120; one with a mental age typical of eight-year-olds would have an IQ of 80. But modern IQ tests arbitrarily define the mean of the population of a given age as being 100 and force the distribution around that mean to have a particular standard deviation—usually 15. So a person whose performance on the test was one standard deviation above the mean for his or her age group would have an IQ of 115.

To give you an idea of what an IQ difference of 15 points means, a person with an IQ of 100 might be expected to graduate from high school without much distinction and then attend a year or two of a community college, whereas a person with an IQ of 115 could expect to graduate from college and might go on to become a professional or fairly high-level business manager. In the other direction, someone with an IQ of 85, which is at the bottom of the normal range, is a candidate for being a high school dropout and could expect a career cap of skilled labor.

Although IQ tests were designed to predict school achievement, it quickly became apparent that they were measuring something that overlaps substantially with ordinary people’s understanding of what intelligence is. At any rate, people’s ratings of other people’s intelligence correlate moderately well with the results of IQ tests. Those who are rated higher in intelligence by ordinary people also get higher IQ test scores.

There are a huge number of IQ tests, but there is not much difference among the reasonably comprehensive ones, and the typical correlation between any two tests, even those having rather different apparent content, is in the range of .80 to .90.

Tests of intelligence sometimes measure quite specific skills such as spelling ability and speed of reasoning. Such highly specific tests tend to correlate with one another in clusters. For example, tests of memory tend to be correlated. The same is true for tasks measuring visual and spatial perception of various kinds (for example, arranging colored blocks to match a two-dimensional design) and for tasks measuring verbal knowledge (for example, vocabulary). All tests of anything that you would be likely to call intelligence are correlated at least to some degree. (For that matter, everything that a society holds to be good is correlated with every other good thing to some degree. Life is unfair.)

BOX 1.1 Subtests Employed on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC)

|

Information: |

What continents lie entirely south of the equator? |

|

Vocabulary: |

What is the meaning of derogatory? |

|

Comprehension: |

Why are streets usually numbered in order? |

|

Similarities: |

How are trees and flowers alike? |

|

Arithmetic: |

If six oranges cost two dollars, how much do nine oranges cost? |

|

Picture Completion: |

Indicate the missing part from the incomplete picture. |

|

Block Design: |

Use blocks to replicate a two-color design. |

|

Object Assembly: |

Assemble puzzles depicting common objects. |

|

Picture Arrangement: |

Re-arrange a set of scrambled pictures so that they describe a meaningful set of events. |

|

Coding: |

Match symbols with shapes using a key as a guide. |

As an example of a particular IQ test, Box 1.1 shows subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC), which can be given to children aged six to sixteen. Correlations among subtests of IQ tests like this are in the vicinity of .30 to around .60. That they are correlated is reflected in the notion that there is something that corresponds to general intelligence, a construct known as the g factor. (Factor has a technical meaning that is unnecessary for us to pursue. The g factor is itself highly correlated with IQ score, but it is slightly different from IQ score in respects that needn’t concern us here.) Some subtests better correlate with the g factor than others, and we say that they have high g loadings. The Vocabulary subtest, for example, is highly correlated with g, whereas Coding (matching symbols using a key) is not.

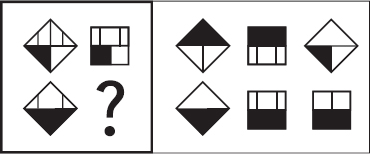

Figure 1.1. A problem similar to those on the Raven Progressive Matrices test. From Flynn ( 2007. Reprinted with permission.

The Two Types of IQ

There are actually two components to g or general intelligence. One is fluid intelligence, or the ability to solve novel, abstract problems—the type requiring mental operations that make relatively little use of the real-world information you have been obtaining over your lifetime. Fluid intelligence is exercised via the operation of so-called executive functions. These include “working memory,” “attentional control,” and “inhibitory control.” The information that you must sustain constantly in your mind in order to solve a problem, and that requires some effort to maintain, is said to be held in working memory. Attentional control is the ability not only to sustain attention to relevant aspects of the problem but also to shift attention when needed to solve the next step in the problem. And inhibitory control is the ability to suppress irrelevant but tempting moves.

Figure 1.1 shows a classic example of a problem that tests fluid intelligence. It’s from the Raven Progressive Matrices. The word matrices refers to the collection of figures in the problems—arrayed as 2 × 2 or 3 × 3 matrices. The word progressive refers to the fact that the problems get harder and harder. John C. Raven published the first version of the test in 1938.

The example that the problem-solver must follow is set up by the two figures in the top row of the left panel. The figure at the left in the bottom row then specifies what has to be transformed in order to solve the problem. The six figures on the right correspond to the answer alternatives. The solution of the problem requires you to notice that the figure in the upper left of the left panel is a diamond and the figure in the upper right is a square. This tells you that the answer has to be a square. Then you must notice that the bottom half of the upper diamond is divided into two, with the left portion in black. The fact that the left half of the figure on the right is also black tells you that the corresponding portion of the square on the bottom right must match the corresponding portion in the lower left diamond—that is, the entire bottom half must be black. Then you notice that to make the top right figure, one of the bars has been removed from the top left diamond while symmetry of the bars has been preserved. This establishes that you must remove one of the bars of the square at the bottom while preserving symmetry. Now you know that the correct answer must be the square at the bottom right of the answer panel.

Of the subtests on the WISC shown in Box 1.1, the ones that most involve fluid intelligence are Picture Completion, which requires you to attend to all aspects of a figure and analyze which portion of it is missing; Block Design, which requires you to operate with purely abstract visual materials; Object Assembly, which requires going back and forth between your knowledge of what the desired object looks like and the abstract shapes that must be used to compose it; Picture Arrangement, which requires you to hold in working memory the various pictures and to rearrange them mentally until a coherent story is told by the pictures in a given order; and Coding, which is a completely abstract task that measures primarily speed of information processing. Scores on these types of tests are sometimes said to comprise the Performance IQ, referring to the fact that all of the subtests require performing operations of some kind. These operations are brought to bear on the spot and draw only somewhat on stored knowledge.

The other type of general intelligence is called crystallized intelligence. This is the store of information that you have about the nature of the world and the learned procedures that help you to make inferences about it. The subtests on the WISC that tap crystallized intelligence most heavily are Information, Vocabulary, Comprehension, Similarities, and Arithmetic. Doing arithmetic, of course, involves both calling up stored or crystallized knowledge and performing operations, most if not all of which have been learned previously. The WISC creators refer to the total of the scores on this collection of subtests as Verbal IQ, since most of the information being drawn upon is verbal in nature. The score that combines Performance IQ with Verbal IQ is called Full Scale IQ.

How do we know that there are two fundamentally different types of general intelligence? We know this first because the subtests that we describe as performance-oriented clearly draw relatively more on reasoning skills (fluid intelligence) than on knowledge (crystallized intelligence), and the subtests that we call verbal clearly depend relatively more on knowledge (including knowledge about algorithmic solutions) than on reasoning skills. Also, the verbal subtests have higher correlations with one another than they do with the performance subtests, and vice versa.

In addition, the subtests that we call measures of fluid intelligence rest on executive functions that are mediated by a portion of the frontal cortex called the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and another region linked in a network with the PFC called the anterior cingulate. The destruction of the PFC has devastating consequences for mental tasks that require the executive functions of working memory, attentional control, and inhibitory control. People with severe damage to the PFC may be so incapable of solving Raven matrices that they function at the level of mentally retarded people on that test, yet have crystallized intelligence that is entirely normal. The opposite pattern also occurs. Autistic children usually have impaired crystallized intelligence but may have normal or even superior fluid intelligence.

As one would expect given the lesion evidence, the PFC is particularly active, as demonstrated in brain-imaging studies, when people attempt to solve problems that make substantial use of fluid intelligence, such as the Raven matrices and difficult mathematical problems.

Additional evidence for the two types of intelligence is that fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence have quite different trajectories over a lifetime. Figure 1.2 shows an idealized version of those trajectories. The growth of fluid intelligence is rapid over the first years of life but begins to decline quite early. Already by the early twenties, fluid intelligence shows some decline. Mathematicians and others who work with symbolic, abstract materials for which they must invent novel solutions may find their powers fading somewhat by the age of thirty. By seventy years old, fluid intelligence is noticeably less than it has been—more than one standard deviation lower. Older people find it harder to solve puzzles and mazes. Crystallized intelligence, on the other hand, may continue to increase over the lifespan, at least until very old age. Historians and others whose best work depends on a large storehouse of information may find their powers increasing well into their fifties.

Figure 1.2. Schematic rendering of fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence over the life span. From Cattell ( 1987).

Note that everything I have just written about the age trajectories of fluid and crystallized intelligence is controversial to some degree. I will spare you the ins and outs of this controversy and simply say that the universally agreed-upon fact is that fluid intelligence begins to decline earlier than crystallized intelligence.

That fluid intelligence declines earlier in life than crystallized intelligence could be predicted by the fact that the PFC shows deterioration earlier than other structures in the brain.

A final source of evidence that the two types of intelligence exist is that executive functions and overall IQ may be separately heritable. Executive functions are inherited to a degree from parents, and so is crystallized intelligence, or the knowledge that helps people solve problems. A person can inherit relatively high executive function from parents who have relatively high executive function, yet can inherit relatively low crystallized intelligence from the same parents who score relatively low on this dimension.

Fluid intelligence is more important to good intellectual functioning for younger people than it is for older people. For young children, the correlation between fluid intelligence and reading and math skills is higher than that for crystallized intelligence. In contrast, for older children and adults, the correlation between crystallized intelligence and reading and math skills is higher than that for fluid intelligence. This point becomes crucial later, when I discuss some of the reasons for the relatively low IQ of people of lower socioeconomic status and members of some minority groups, and some of the possible ways to improve IQ.

Another extremely important fact about fluid intelligence is that the PFC has substantial interconnections with the limbic lobe, which is heavily involved in emotion and stress. During emotional arousal, there is less activity in the PFC, and so fluid-intelligence functioning is worse. Over time, continued stress may result in permanently reduced PFC function. This information too becomes critical later, when I discuss the modifiability of fluid-intelligence functioning for the poor and minorities.

In the meantime, however, I focus on the simple IQ score, combining fluid and crystallized intelligence, and make distinctions between the two types of intelligence when that is important.

Varieties of Intelligence

What do IQ scores predict? First of all, they predict academic grades. This is scarcely surprising, because that is why Alfred Binet invented IQ tests more than a hundred years ago. He wanted to be able to determine which children would be unlikely to benefit from normal education and therefore would require special treatment. The correlation today between the scores on typical intelligence tests and the grades of schoolchildren is about .50. That value is substantial, but it leaves room for a great many variables that are not measured by an IQ test to play a role in predicting academic performance.

IQ tests tend to measure what has been called “analytic” intelligence as distinct from “practical” intelligence. Analytic problems typically have been constructed by other people; are clearly defined; have all the information necessary to solve them embedded in their description; have only one right answer; usually can be reached only by one particular strategy; are often not closely related to everyday experience; and are not particularly interesting in their own right. These can be contrasted with “practical” problems, which require recognition that there is something to be solved; are usually not well defined; typically require seeking out information relevant to their solution; have several different possible solutions; are often embedded in everyday experience and require such experience for their solution; and engage—and usually require—intrinsic motivation.

Robert Sternberg measures practical intelligence with questions asking people, for example, how to handle problems like entering a party where one does not know anyone, discussing what share of rental payments is fair for each of several people, and writing a letter of recommendation for someone who is not well known to the person writing it.

Sternberg also writes about a third type of intelligence, which he calls “creative” intelligence. This is the ability to create, invent, or imagine something. He measures creative intelligence by, for example, giving people a title, such as “The Octopus’s Sneakers” or “A Fifth Chance,” and asking them to write the story. He also measures creative intelligence by asking people to look at a sequence of pictures and having them tell a story about one of them, and by having people develop advertisements for new products.

When Sternberg measures analytic intelligence in the standard way, by SAT or ACT scores or IQ tests, and practical and creative intelligence by his novel measures, he finds that his practical and creative measures add to the predictability of outcomes such as success in school and work performance. Sometimes the increments in predictability are substantial; in fact they sometimes outperform IQ tests by a significant margin.

Sternberg is highly persuasive when he talks about three hypothetical graduate students. Analytic Alice is brilliant in discussion of ideas and is a superb critic of the products of others. Creative Cathy is not so incandescent in her treatment of ideas, but she comes up with lots of interesting notions of her own, a certain fraction of which end up paying off. Practical Patty is neither analytically brilliant nor especially innovative. But she can figure out a way to get the job done. She can get from here to there in sensible, cost-effective ways.

What you hope for are colleagues with all three types of intelligence, of course, but especially when you work on a team, even the people who stand out in only one dimension have a vital role to play. It is worth noting that Sternberg’s measures of practical and creative intelligence show much less of a separation between minority and majority groups than do analytic tests, meaning that they become a way to bring more minorities into educational and occupational roles where their entrance might be blocked by tests of analytic intelligence.

Howard Gardner argued that IQ tests measure only linguistic, logical-mathematical, and spatial abilities but neglect other “intelligences.” These include various “personal intelligences” resembling the “emotional intelligence” that social psychologist Peter Salovey and his colleagues researched. Emotional intelligence includes being able to accurately perceive emotion, using emotions to facilitate thinking, understanding emotions, and managing emotions in self and others. Emotional intelligence as measured by Salovey and his colleagues is virtually uncorrelated with analytic intelligence as measured by IQ tests, but it predicts peer and supervisor ratings of dimensions like interpersonal sensitivity, sociability, contributing to a positive work environment, stress tolerance, and leadership potential. Some might want to avoid the term intelligence for these measures of emotional skills, but that is a quibble.

The other intelligences that Gardner discussed are “musical” and “bodily kinesthetic.” Some intelligence researchers are utterly contemptuous of using the term intelligence for these skills. But there are such things as musical and kinesthetic ideas, and there are such things as musical and kinesthetic problems to be solved. I’m personally willing to call Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony and Alvin Ailey’s “Revelations” works of genius. So I am perfectly content to say that the skills that invented those works are the products of intelligence. But I wouldn’t try to press my personal preference on others who are resistant to that label.

Gardner justified his lengthening of the list of intelligences by pointing out that there are child prodigies for most of them, and there is neurological evidence that different areas of the brain are specialized for each of the intelligences he identified. Whether one calls his additions to the intelligence list mere skills or something else, it is clear that they are somewhat separate from the standard analytic ones and that measures of them predict—or in principle could predict—important aspects of skilled human endeavor that the standard tests do not.

Motivation and Achievement

Finally, characteristics that no one would call intelligence have a marked effect on academic and occupational achievement.

Decades ago, personality psychologist Walter Mischel studied the ability of children to delay gratification. He put preschoolers from a Stanford University nursery school into a room (alone, they thought, but with an experimenter watching their every move) where there was a cookie, a marshmallow, a toy, or some other desirable object. The children were told that they could have the object whenever they wanted. They had only to ring a bell and then the experimenter would come in and let them have the object. Or they could wait until the experimenter returned of his own accord. If they waited that long they could have two cookies, marshmallows, or toys. The dependent measure is called the “delay of gratification.” The longer the child waits before ringing the bell, the greater the ability to delay gratification.

Mischel then waited more than a decade, until these mostly upper-middle-class kids were in high school. The children who had waited the longest before taking the goodie were rated by their parents as being better able to concentrate, better planners, and better able to tolerate frustration and to deal maturely with stress. These traits paid off in tests of measured academic intelligence. The greater the toddler’s ability to delay gratification, the higher the SAT score in high school. The correlation between delay time of the toddler and the SAT Verbal score was .42; the correlation for the SAT Math score was .57. It is possible that the brighter toddlers are the ones who had the longer delay times, but it seems unlikely that this is the whole explanation. More plausible is that children who were better able to resist temptation were better able to hit the books when they got older. This is not the last time we will have occasion to note that SAT scores, which correlate highly with IQ scores, are not equivalent to IQ. Some cultural groups do better on SAT scores than would be predicted by their IQ—for reasons that probably have to do with motivation.

That motivational factors affect academic achievement levels is scarcely shocking. That motivation may sometimes actually be a better predictor of academic achievement than IQ is, however, a surprise. This is what an extremely important study found for eighth-graders at a magnet school in a large city in the Northeast. Psychologists Angela Duckworth and Martin Seligman measured self-discipline in a variety of ways. They asked the students about the degree to which they said and did things impulsively; they quizzed the students about different kinds of rewards, asking them about the degree to which they would prefer a small, immediate version of the reward versus a large, delayed reward; they actually offered the children one dollar immediately versus the opportunity to get two dollars a week later; and they asked parents and teachers about each student’s ability to inhibit behavior, follow rules, and control impulsive reactions. They combined scores on all of these measures into a single omnibus measure of self-discipline and then compared how well this measure predicted grades versus how well a standard IQ test predicted grades. The result: the IQ test was not nearly as good a predictor of grades as the motivational measure. The correlation for IQ was a very modest .32. The correlation for self-discipline was more than twice as high—.67. The self-discipline measure was a slightly better predictor of standard school achievement test scores than was IQ—.43 versus .36, though the difference was not statistically significant. If you had to choose for your child a high IQ or strong self-discipline, you might be wise to pick the latter.

The results of the Duckworth and Seligman study, important as they are, need to be replicated. The differences between self-discipline and IQ as predictors of achievement might not be the same at a nonselective school or even another magnet school. Nevertheless, the study stands as proof of the hypothesis that motivational factors can count more than IQ as a predictor of achievement.

Let’s draw together some of the lessons of the research I have been describing.

IQ is only one component of intelligence. Practical intelligence and creative intelligence are not well assessed by IQ tests, and these types of intelligence add to the predictability of both academic achievement and occupational success. Once we have refined measures of these types of intelligence, we may find that they are as important as the analytic type of intelligence measured by IQ tests.

Intelligence of whatever kind and however measured is only one predictor of academic and occupational success. Emotional skills and self-discipline and quite possibly other factors involving motivation and character are important for both.

To these qualifications of the importance of IQ, we can add the fact that, above a certain level of intelligence, most employers do not seem to be after still more of it. Instead, they claim that they’re after strong work ethic, reliability, self-discipline, perseverance, responsibility, communication skills, teamwork ability, and adaptability to change.

So IQ is not the be-all and end-all of intelligence, and intelligence, even when defined more broadly than IQ score, is not the only important factor influencing academic success or occupational attainment. And academic success is itself only one predictor of occupational success.

What IQ Predicts

Nevertheless, IQ and academic success are associated with a great many outcomes. But it is surprisingly difficult to specify exactly what the causal pathways are. Researchers often determine the individual’s contemporary IQ or IQ earlier in life, socioeconomic status of the family of origin, living circumstances when the individual was a child, number of siblings, whether the family had a library card, the educational attainment of the individual, and other variables, and put all of them into a multiple-regression equation predicting adult socioeconomic status or income or social pathology or whatever. Researchers then report the magnitude of the contribution of each of the variables in the regression equation, net of all the others (that is, holding constant all the others). It always turns out that IQ, net of all the other variables, is important to outcomes. But as I make clear in Appendix A on statistics, the independent variables pose a tangle of causality—with some causing others in goodness-knows-what ways and some being caused by unknown variables that have not even been measured. Higher socioeconomic status of parents is related to educational attainment of the child, but higher-socioeconomic-status parents have higher IQs, and this affects both the genes that the child has and the emphasis that the parents are likely to place on education and the quality of the parenting with respect to encouragement of intellectual skills and so on. So statements such as “IQ accounts for X percent of the variation in occupational attainment” are built on the shakiest of statistical foundations. What nature hath joined together, multiple regression cannot put asunder.

But it is possible to get a much firmer bead on the importance of IQ in determining life outcomes. Political scientist Charles Murray has looked at people whose IQs were measured by the Armed Forces Qualification Test as part of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth begun in the late 1970s. He examined income and other social indicators for the original group when they were adults many years later. But he did this for a highly selected sample—sibling pairs who were not born into poverty (that is, their income was higher than the lowest quartile of income), who were not illegitimate, and whose parents were together at least up until the child was seven. But the pairs had to differ in IQ. Each person either had an IQ in the normal range—from 90 to 109—or had one outside that range. The sibling with an IQ outside that range could either be bright (110–119), very bright (120+), dull (80–89), or very dull (less than 80).

Murray could ask for this sample, which he called “utopian,” how much difference it made to have IQ in the normal range versus outside that range in one direction or another. The firmest measure that he had was the income of the individuals as adults. Income, of course, is correlated with occupational attainment and social class, so when we look at income we can treat it as a proxy for these other variables as well. He also had good data on whether the women in the sample had given birth to illegitimate children. This variable too can be taken as a proxy for a large number of other variables, in this case some involving social dysfunction such as likelihood of incarceration and likelihood of being on welfare.

What Murray found is that even in this stable, mostly middle-class group of siblings, different IQs are associated with very different outcomes. Table 1.1 shows that if a person had a normal-IQ sibling but was very bright himself or herself, the very bright sibling made more than a third more money (and thus would have had on average a substantially higher-status job). If a person had a normal-IQ sibling but was himself or herself very dull, the very dull sibling made less than half as much as the normal-IQ sibling. Illegitimate births were also very much tied to IQ. Very dull women were two and a half times as likely to have illegitimate children as their normal-IQ siblings.

TABLE 1.1 Relationship between IQ and income and percentage of women having illegitimate children, for siblings from the same stable, middle-class family who differ in IQ

|

IQ Group |

Income |

Illegitimacy Rate (%) |

|

Very bright siblings (120+) |

$70,700 |

2 |

|

Bright siblings (110–119) |

$60,500 |

10 |

|

Reference group (90–109) |

$52,700 |

17 |

|

Dull siblings (80–89) |

$39,400 |

33 |

|

Very dull siblings (< 80) |

$23,600 |

44 |

What is important about these analyses is that they show that members of the same family who have different IQs have very different life outcomes on average. Importantly, the analyses remove from consideration the effects of socioeconomic status of the family of origin, since all of the comparisons are between members of the same family. The analyses do not prove that IQ alone is directly causing those outcomes. For example, it is likely that educational opportunity, which is mediated by IQ, is also an important part of the causal chain. In effect, education probably acts as a multiplier of the effect of IQ. And IQ is undoubtedly associated with aspects of character and motivation that play a role as well. But the results are very telling about the importance of IQ and its correlates even among members of the same, relatively high-status and stable, family.

The IQ scores Murray examined are undoubtedly influenced substantially by genes. Some children in a family get a better luck of the genetic draw from their parents. Murray himself has long been associated with the view that IQ is largely genetically determined, and with the view that, partly because of this, IQ is not very susceptible to influence by environmental factors. But how important are genes, exactly? And what role do they leave for the environment? In the next chapter I pursue the questions regarding the degree to which intelligence is something that is inherited and the degree to which the environment can modify it.