CHAPTER EIGHT

Advantage Asia?

Good grief, those scores are positively Asian.

—One European-American Silicon Valley high school senior to another, upon hearing about her extremely high SAT scores

If there is no dark and dogged will, there will be no shining accomplishment; if there is no dull and determined effort, there will be no brilliant achievement.

—Chinese saying

HERE ARE SOME STATISTICS that should serve to concentrate the minds of people of European descent.

- In 1966, Chinese Americans who were seniors in high school were 67 percent more likely to take the SAT than were European Americans. Despite being much less highly selected, the Chinese Americans scored very close to European Americans on average.

- In 1980—when they were thirty-two years old—the same Chinese Americans from the “class of ’66” were 62 percent more likely to be in professional, managerial, or technical fields than were European Americans.

- In the late 1980s, the children of Indochinese boat people constituted 20 percent of the population of Garden Grove in Orange County, California, but claimed twelve of fourteen high school valedictorians.

- In 1999, U.S. eighth-graders scored between .75 and 1.0 SD below Japan, Korea, China, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong in math and between .33 and .50 SD below those countries in science as indicated by the Third International Mathematics and Science Study.

- Although Asian Americans constitute only 2 percent of the population, all five of the Westinghouse Science Fair winners in 2008 were Asian Americans.

- Asian and Asian American students now constitute 20 percent of students at Harvard and 45 percent at Berkeley.

So European Americans might as well throw in the towel. Asians are just plain smarter.

Actually, probably not. At least not as indicated by traditional IQ tests. Herrnstein and Murray, Rushton and Jensen, Philip Vernon, Richard Lynn, and others have reported that there are IQ differences favoring Asians, but Flynn has shown that such reports are due in good part to the failure of the researchers to report Asian IQs based on contemporary IQ test norms rather than on outmoded norms and to using small and unrepresentative samples. Basing scores on outmoded norms has the effect of erroneously raising Asian IQs. Flynn reviewed sixteen different studies, the results of which were fairly consistent with one another. Most showed that East Asians had slightly lower IQs than Americans.

What is not in dispute is that Asian Americans achieve at a level far in excess of what their measured IQ suggests they would be likely to attain. Asian intellectual accomplishment is due more to sweat than to exceptional gray matter.

The Asian Drive for Achievement

Harold Stevenson and his coworkers studied the intellectual abilities and school achievement of children in three different cities chosen to be highly similar socioeconomically: Sendai in Japan, Taipei in Taiwan, and Minneapolis in the United States. They measured the intelligence and reading and math achievement of random samples of children in the first and fifth grades. We cannot know if the IQ tests really provided measures of intelligence that are fully comparable across the three populations (though the researchers believed they did—and make a pretty good case for that). Nevertheless, in the first grade, the Americans outperformed the Japanese and the Chinese on most intelligence tests. The authors attributed this to the greater effort of American parents to stimulate their preschool kids intellectually. Whatever the reason for the high American performance in the first grade, by the fifth grade the superiority of American children in IQ was gone. From these sets of facts we learn that regardless of who was smarter than whom in the first grade, the Americans had lost considerable ground to the Asian children by the fifth grade.

But the truly remarkable finding of this study was that math achievement of the Asian students was leagues beyond that of the U.S. students. The identical problems were given to Japanese, Taiwanese, and American children. By the fifth grade, Taiwanese children scored almost 1 SD better in mathematics than American children, and the Japanese scored 1.30 SDs better than American children. Even more astonishing, in a more extended study, Stevenson and his coworkers looked at the math performance of fifth-graders in many different schools in China, Taiwan, Japan, and the United States. There wasn’t a lot of difference among the Asian countries. Schools in all three countries performed at about the same level. There was more variability among the U.S. schools. But the very best performance by an American school was equal to the worst performance of any of the Asian schools!

IQ is not the point: something about Asian schools or the motivation of Asian children differs greatly from American schools or American children’s motivation.

Let’s start with the schools. Children in Japan go to school about 240 days a year, whereas children in the United States go to school about 180 days a year. The Asian schools are probably better, but the performance of Asian American children in U.S. schools shows that Asian motivation counts for an awful lot.

The Coleman report on educational equality in the United States, published in 1966, measured the intelligence of a very large random sample of American children, and Flynn followed them until they were thirty-six years old on average. Americans of East Asian descent scored about 100 on the nonverbal portion of IQ tests and about 97 on the verbal portion, so they had a slightly lower overall IQ than did Americans of European descent.

Despite their slightly inferior performance on IQ tests, the Chinese Americans of the class of 1966 were about half as likely as other children to have to repeat a grade in K–12. Foreshadowing things to come, when the Chinese American children were compared with European American children in grade school, they did slightly better on achievement tests. By the time they were in high school, the Chinese Americans were scoring one-third of a standard deviation higher than European Americans on achievement tests. At a given IQ level, the Chinese Americans performed one-half of a standard deviation higher on typical achievement tests, compared with European Americans. The overachievement was particularly great on mathematics tests. In tests of calculus and analytic geometry, the Chinese Americans surpassed European Americans by a full standard deviation. When students were seniors in high school, the Chinese Americans performed about one-third of a standard deviation better on SAT tests than did Americans of the same IQ.

By the age of thirty-two, the determination of the Chinese Americans in the class of 1966 had paid a double dividend. To get the educational credentials to qualify for professional or technical or managerial occupations, they needed a minimum IQ of 93, compared to 100 for whites. More important, of those with the IQ to qualify, fully 78 percent had the persistence to get their credentials and enter those occupations compared to 60 percent of whites. The resulting total dividend was 55 percent of Chinese Americans in high-status occupations, compared to a third of whites. The number for Japanese Americans was about halfway between the numbers for these two groups.

Flynn found similar overachievement relative to IQ on achievement tests and in occupations in a wide variety of studies of East Asians.

Notice that the overachievement of Asian Americans, as indicated by the marked difference between measured IQ and academic achievement, is sufficient by itself to establish that achievement tests such as those given in K–12 classrooms and the SAT are not merely IQ tests by another name. They measure intellectual achievement as opposed to the power of memory, perception, and reasoning of the kind that IQ tests measure. Note also that the overachievement of Asian Americans establishes that academic achievement can be a better predictor of ultimate socioeconomic success than IQ.

Recently, Flynn studied the children of the members of that original class of 1966. Since we know that being raised in homes of higher social class is associated with higher IQ, we would expect the children to have higher IQs than not only their own parents but also the population at large. And indeed they did. The mean of the Chinese American children when they were preschoolers was 9 points higher than the white average. But then most went to ordinary American schools, which we would expect would not be ideal for their intellectual development. In fact, the average of their IQs steadily declined until it was only 3 points above the white mean by the time they were adults.

Notice the arbitrariness of describing what Asians accomplish as overachievement. I used the phrase “Asian overachievement” to a Korean friend who had just spent a year in the United States, where his children attended public schools. “What do you mean by ‘Asian overachievement’?,” he expostulated. “You should say ‘American underachievement’!” He told me that he was astonished when he attended ceremonies at the end of the year for his daughter’s school and discovered that an award was given for having done all of the homework assignments. His daughter was one of two recipients of the award. To him, giving an award for doing homework was about as preposterous as giving an award for eating lunch. It is taken absolutely for granted by Asians. He is right to insist that the phenomenon is one of American underachievement. It’s quite reasonable to regard high achievement as the default state of affairs and what most Americans do as slacking to one degree or another.

My Korean friend’s bemusement touches on the key to understanding Asian achievement magic.

Asian and Asian American achievement is not mysterious. It happens by working harder. Japanese high school students of the 1980s studied 3½ hours a day, and that number is likely to be, if anything, higher today. The high-school-age children of the Indochinese boat people studied 3 hours a day. American high school students in general study an average of 1½ hours a day. (Black eighth-grade children in Detroit study, on average, 2 hours per week. Of course, at least some of this failure to do homework would have to be attributed to a school milieu that does not expect much.)

There is also no mystery about why Asian and Asian American children work harder. Asians do not need to read this book to find out that intelligence and intellectual accomplishment are highly malleable. Confucius set this matter straight twenty-five hundred years ago. He distinguished between two sources of ability, one by nature—a gift from Heaven—and one by dint of hard work.

Asians today still believe that intellectual accomplishment—at any rate, doing well in math in school—is primarily a matter of hard work, whereas European Americans are more likely to believe it is mostly a matter of innate ability or having a good teacher. Asian Americans have attitudes on this topic that are in between those of East Asians and European Americans.

Asians and Asian Americans have another motivational advantage over Westerners and European Americans. When they do badly at something, they respond by working harder at it. A team of Canadian psychologists brought Japanese and Canadian college students to a laboratory and had them work on creativity tests. After the study participants had been working on them for a while, the researchers thanked them and told them about how well they did. Regardless of how well they had actually done, the researchers told some of the participants that they had done very well and others that they had done rather badly. The investigators then gave the participants a similar creativity test and told them to spend as much time as they wanted on it. The Canadians worked longer on the creativity test if they had succeeded on the first one than if they had done badly, but the Japanese worked longer on the creativity test if they had failed on the first one than if they had succeeded.

Persistence in the face of failure is very much part of the Asian tradition of self-improvement. And Asians are accustomed to criticism in the service of self-improvement in situations where Westerners avoid it or resent it. For example, Japanese schoolteachers are observed in their classrooms for at least ten years after they begin teaching. Their fellow teachers give them feedback about their teaching techniques. It is understood in Japan that you cannot be a good teacher without many years of experience. In the United States, we tend to toss teachers into the classroom and assume they can do a good job from the get-go. Or if not, it’s because they haven’t got what it takes.

But a still more important reason for Asians making the most of their natural intelligence is that their culture—as channeled to them by their families—demands it. In the case of Chinese culture, the emphasis on academic achievement has been present for more than two thousand years. A bright Chinese boy who worked hard and did well on the mandarin exams could expect to elevate himself to a well-paying high government position. This brought honor and wealth to his family and his entire village—and the hopes and expectations of his family and fellow villagers were what made him do the work. There was substantial upward mobility via education in China a couple of millennia before this was the case in the West.

So Asian families are more successful in getting their children to achieve academically because Asian families are more powerful agents of influence than are American families—and because what they choose to emphasize is academic achievement.

Eastern Interdependence and Western Independence

Why should Asian families be such powerful agents of influence? Here I need to step back a bit and note some very great differences between Asian and Western societies. Asians are much more interdependent and collectivist than Westerners, who are much more independent and individualist. These East-West differences go back at least twenty-five hundred years to the time of Confucius and the ancient Greeks.

Confucius emphasized strict observance of proper role relations as the foundation of society, the relations being primarily those of emperor to subject, husband to wife, parent to child, elder brother to younger brother, and friend to friend. Chinese society, which was the prototype of all East Asian societies, was an agrarian one. In these societies, especially those that depend on irrigation, farmers need to get along with one another because cooperation is essential to economic activity. Such societies also tend to be very hierarchical, with a tradition of power flowing from the top to the bottom. Social bonds and constraints are strong. The linchpin of Chinese society in particular is the extended family unit. Obedience to the will of the elders was, and to a substantial degree still is, an important bond linking people to one another.

This traditional role of the family is still a powerful factor in the relations of second-and even third-generation Asian Americans and their parents. I have had Asian American students tell me that they would like to go into psychology or philosophy but that it is not possible because their parents want them to be a doctor or an engineer. For my European American students, their parents’ preferences for their occupations are about as relevant to them as their parents’ taste in art.

The Greek tradition gave rise to a fundamentally new type of social relations. The economy of Greece was based not on large-scale agriculture but on trade, hunting, fishing, herding, piracy, and small agribusiness enterprises such as viniculture and olive oil production. None of these activities required close, formalized relations among people. The Greeks, as a consequence, were independent and had the luxury of being able to act without being bound so much by social constraints. They had a lot of freedom to express their talents and satisfy their wants. The individual personality was exalted and considered a proper object of commentary and study. Roman society continued the independent, individualistic tradition of the Greeks, and after a long lull in which the European peasant was probably little more individualist than his Chinese counterpart, the Renaissance and then the Industrial Revolution took up again the individualist strain of Western culture and even accelerated it.

It is hard for someone steeped only in European culture to comprehend the extent to which achievement in the East is a family affair and not primarily a matter of individual pride and status. Like the ancient candidate for mandarin status, one achieves because it is to the benefit of the family—both economically and socially. Although there may be pride in personal accomplishment, achievement is not primarily a matter of enriching oneself or bringing honor to oneself.

And—here’s the big advantage of Asian culture—achievement for the family seems to be a greater goad to success than achievement for the self. If I, as an individual Western free agent, choose to achieve in order to bring myself honor or money, that is my decision. And if I decide that my talents are too meager or I don’t want to work hard, I can choose to opt out of the rat race. But if I am linked by strong bonds to my family, and fed its achievement demands along with my meals, I simply have no choice but to do my best in school and in professional life thereafter. And the demand is reasonable because it has been made clear to me that my achievement is a matter of will and not just innate talent.

The achievement advantage of Asian Americans over European Americans is likely to increase. Prior to 1968, Asian immigrants to the United States were probably not more natively intelligent than their compatriots who remained at home. But the immigration laws of the 196os make it relatively easy to come to the United States for a person who is a professional and relatively hard for someone who is not. The Asian American newcomers are going to have a cultural advantage over European Americans in general because they are professional and managerial types as well as being East Asians. Both their social class and their culture are going to be favorable for the maximum development of educational and professional success of their children. And their children are going to have a genetic advantage as well because of the selection for talent. (This genetic advantage is likely to be slight. As we will see in the next chapter, environmental bottlenecks do not have much effect on the IQ of generations after the bottleneck.)

Holistic and Analytic Habits of Thought

The cultural differences of East and West result not just in quantitative differences in intellectual achievement but also in qualitative differences in habits of mind. Effective functioning for East Asians depends on integrating one’s own desires and actions with those of others. Harmony has been the watchword for social relations for twenty-five hundred years in China. Effective functioning for Westerners is not so dependent on dealing with others. Westerners have the luxury of acting independently of the wishes of other people.

These social differences have given rise to habits of mind on the part of Easterners that I describe as holistic. Easterners pay attention to a wide range of objects and events; they are concerned with relationships and similarities among those objects and events; and they reason using dialectical forms of thought, which includes finding the “middle way” between opposing ideas. Western perception and thought are analytic, which is to say that Westerners focus on a relatively small part of the environment, some object or person that they wish to influence in some way; they attend to the attributes of that small part with a view toward categorizing it and modeling its behavior; and they often reason using formal rules of logic.

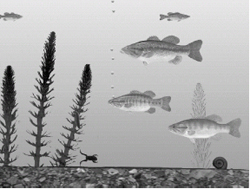

The need to attend to others means that the perception of Easterners is directed outward to a broad swath of the social environment and, as a consequence, to the physical environment as well. Takahiko Masuda and I showed people brief animated films of underwater scenes and then asked them to tell us what they had seen. Take a look at Figure 8.1, which shows a still photo taken from one of the films. The Americans focused primarily on the most salient objects—large, rapidly moving fish, for example. A usual first response would be, “I saw three big fish swimming off to the left; they had pink spots on their white bellies.”

Figure 8.1. Still photo from a color animation film shown to Japanese and Americans who were asked to report what they saw. From Masuda and Nisbett (2001).

The Japanese reported seeing much more of the environment—rocks, weeds, inanimate creatures such as snails. A typical initial response would be, “I saw what looked like a stream; the water was green; there were rocks and shells on the bottom.” In addition to paying attention to context, the Japanese noticed relationships between the context and particular objects in it. For example, they were inclined to note that one object was next to another or that a frog was climbing on a plant. Altogether, the Japanese were able to report 60 percent more details about the environment than were Americans.

In another study, Masuda demonstrated that when shown cartoon pictures of a central figure flanked by other people and asked to judge the mood of the central figure, the Japanese were much more influenced in their judgments by the expressions on the surrounding faces than were the Americans.

Asians and Westerners see different things because they are looking at different things. My coworkers and I have rigged people up with devices that can measure what part of a picture they are looking at every millisecond. Chinese spend more time looking at the background than do Americans and make many more eye movements back and forth between the most salient object and the background.

The greater attention to context allows East Asians to make correct judgments about causality under circumstances where Americans make mistakes. Social psychologists have uncovered what they call “the fundamental attribution error.” People are prone to overlook important social and situational causes of behavior and attribute the behavior instead to what they assume are attributes of the actor—personality traits, abilities, or attitudes. For example, when reading an essay that an instructor in a course or an experimenter in a psychology study has asked someone to write in favor of capital punishment, Americans assume that the writer must hold the view that he expressed. And they do this even when the experimenter has just requested that they write an essay upholding a view the experimenter chose. Koreans in this situation correctly make no assumption that the person whose essay they read actually holds the position he takes in the essay.

The greater attentiveness to context has been characteristic of East Asians since the time of the ancient Chinese, who understood the concept of action at a distance. This made it possible for them to understand the principles of magnetism and acoustics and allowed them to figure out the true cause for the tides (which escaped even Galileo). Aristotle’s physics, in contrast, was completely focused on the properties of objects. In his system, a stone fell to the bottom when dropped in water because it had the property of gravity, and a stick of wood floated on the water because it had the property of levity. There is no such property as levity, of course, and gravity is not found in objects but in the relation between objects.

Despite the greater correctness of ancient Chinese physics, and despite the fact that China was leagues ahead of the Greeks in technological achievements, it was the Greeks who invented formal science. Two things made this possible for the Greeks.

First, because the Greeks were fixated on objects, they were concerned with the attributes of objects and with determining the categories to which they belonged. In order to understand the behavior of objects, the Greeks invented rules that presumably governed the behavior of objects. And rules and categories are what constitute science at base. Without them, there can be no explicit, generalizable models of the world to test. There can only be technology, no matter how sophisticated.

Second, the Greeks invented formal logic. As the story goes, Aristotle had gotten impatient with hearing poor arguments in the marketplace and the political assembly and so came up with logic in order to rule out forms of argument that are defective. In any case, logic does in fact serve that function in the West.

Logic was never of much interest in China. In fact, it appeared just once, briefly, in the third century BC, and it was never formalized. The Greeks could invent logic precisely because their habit of argumentation was socially acceptable. In ancient China, and in most of East Asia today, disagreements are a risky business—you might make an enemy if you contradict another person’s point of view. Instead of logic, the abstract reasoning patterns of the East tend toward dialecticism, including a concern with finding the “middle way” between opposing arguments and an emphasis on integrating different points of view.

Like rules, categories, and explicit models, formal logic is an extremely helpful tool for science. But the Greeks went overboard in their fondness for logical argument. They rejected the concept of zero because, they reasoned, zero was equivalent to “non-being” and non-being cannot be! And Zeno’s famous paradoxes are the result of logic gone wild. (For example, motion is impossible. For an arrow to reach a target, it would have to go half the distance between the bow and the target, then half that distance, and so on ad infinitum, and thus could never reach its target. This strikes us as comical, but the Greeks thought this was a real stumper.)

Social practices and habits of thought tend to get ingrained, and so contemporary social and cognitive differences between East and West are much like those of ancient times. Thus we might expect Westerners to be more likely to emphasize rules, categories, and logic, and Easterners to be more likely to emphasize relationships and dialectical reasoning. And, in fact, my coworkers and I find this to be the case.

When we presented people with three words such as cow, chicken, and grass, and asked them which two go together, we got very different answers from Easterners and Westerners. Americans were more likely to say cow and chicken go together because they are both animals; that is, they belong to the same taxonomic category. Asians, however, focusing on relationships, were more likely to say that cow goes with grass because a cow eats grass.

We also presented syllogisms to Americans and Asians and asked them to judge the validity of their conclusions. We found that Asians are just as good as Americans at judging the validity of syllogisms that are stated in abstract terms—all As are X, some Bs are Y, and so on—but are likely to be led astray when dealing with familiar content. Asians are inclined to judge conclusions that follow from their premises to be invalid if they are implausible (e.g., All mammals hibernate/rabbits do not hibernate/rabbits are not mammals). And Asians are likely to judge as valid conclusions that are in fact invalid but which are plausible.

Finally, it is possible to show that Americans sometimes make mistakes in reasoning owing to the same kind of “hyperlogical” stance that characterized the ancient Greeks. My coworkers and I showed that Americans will sometimes judge a given plausible proposition to be more likely to be true if it is contradicted by a less plausible proposition than if it is not contradicted. The Americans assume that if there is an apparent contradiction between two propositions, the more plausible one must be true and the less plausible one must be false. Asians make the opposite error of judging a relatively implausible proposition to be more likely to be true if it is contradicted by a more plausible proposition than if it is not contradicted—because they are motivated to find truth in both of two opposing propositions.

These perceptual and cognitive differences rest on brain activity that differs between Easterners and Westerners. For example, when Chinese are shown animated pictures of underwater scenes, an area of the brain known to respond to backgrounds and contexts is more active than it is for Americans. Conversely, an area of the brain known to respond to salient objects is less active for Asians than it is for Americans. Another brain-function study pursued the fact that Americans find it easier to make judgments about objects while ignoring their contexts, and East Asians find it easier to make judgments about objects which take into account their context. Consistent with this fact, regions of the frontal and parietal cortices that are known to be involved in attention control are more active when a person makes judgments of the nonpreferred, more difficult kind—that is, judgments taking into account contexts for Americans and judgments that require ignoring contexts for East Asians.

How do we know that these differences in perception and thought are social in origin and not genetic? There are two main reasons. First, in several of the studies we conducted, we compared Asians, Asian Americans, and European Americans. In all the studies the Asian Americans perceived and reasoned in ways that were intermediate between Asians and European Americans, and were usually more similar to those of European Americans. Second, Hong Kong is known to be a bicultural society, with Chinese customs mingling with English ones. We found residents of Hong Kong to reason in a fashion intermediate between how Chinese and European Americans reason. And when Hong Kong residents were asked to make causal attributions about the behavior of fish, they reasoned like Chinese after being shown pictures such as temples and dragons and like Westerners after being shown pictures such as Mickey Mouse and the U.S. Capitol!

Eastern Engineers and Western Scientists?

The different social inclinations and thought patterns of Easterners and Westerners have implications for doing well in engineering versus science.

Everyone has heard the cliché that Japanese make good engineers but lag in science. This is no mere stereotype. Japanese prowess in engineering is the wonder of American industry. And my colleagues who teach engineering and my friends who hire engineers tell me that not only are there more Asian American engineers per capita but they also make better engineers than European Americans on average.

However, in the decade of the 1990s, forty-four Nobel Prizes in science were awarded to people living in the United States, the great majority of whom were Americans, and only one was awarded to a Japanese. This is not entirely the result of a difference in funding. The Japanese have spent roughly 38 percent as much on basic research as have Americans over the last twenty-five years, and they spend twice as much as do Germans, who won five Nobel Prizes in the 1990s. China and Korea have been relatively poor, developing countries until recently, and it is too early to tell how successful their citizens will be in basic science. But it is possible to point to some of the roadblocks in the path to scientific productivity that might apply to all interdependent peoples who are inclined to be holistic thinkers.

First, several social differences between East and West favor Western progress in science. In Japan, which is more hierarchically organized than the West in many respects, and which places a greater value on respect for elders, more research money goes to older, no-longer-productive scientists. I believe that the premium on individual achievement and the respect for personal ambition in the West favors scientific accomplishment. Long hours in the lab do not necessarily do much for the scientist’s family, but they are essential to personal fame and glory. Debate is taken for granted in the West and is regarded as an essential part of the scientific enterprise, but it is considered rude in much of the East. A Japanese scientist recently reported on his amazement at seeing American scientists who were friends sharply disagree with one another—and in public. “I worked at the Carnegie Institution in Washington, and I knew two eminent scientists who were good friends, but once it came to their work, they would have severe debates, even in the journals. That kind of thing happens in the United States, but in Japan, never.”

Second, the Confucian tradition, of which Japan and Korea are a part, has little use for the idea that knowledge is valuable for its own sake. This starkly contrasts with the ancient Greek philosophical tradition, which prized such knowledge above all other kinds. (I emphasize the term philosophical tradition in the preceding sentence. There is an amusing passage in The Republic where an Athenian businessman castigates Socrates for his pursuit of abstract knowledge, telling him that although it is admittedly attractive in the young, it is disgusting in a grown man.)

Third, logic, the intellectual tool of debate, is more readily applied to real-world content by Westerners than by Easterners. Even the occasional hyperlogical habits of Westerners can be useful in science, however clumsy and even comical they can be in everyday life. Related to logic is the Western type of rhetoric found in formal discourse in science, law, and policy analysis. This consists of an overview of what is being discussed, general concerns about the topic, specific hypothesis, operations to test the hypothesis, discussion of pertinent facts, defense against possible counterarguments, and summary of conclusions. Training in this pattern of argumentation begins in nursery school: “This teddy bear is my lovey, I like him because…” Perhaps due to its roots in debate and formal logic, the Western form of rhetoric is not common in the East. I find with my own East Asian students that the standard rhetorical form is the last thing they learn on their way to a PhD.

Finally, there is the matter of curiosity. For whatever reason, Westerners seem to be more curious than Easterners. It is Westerners who have explored the Earth and immersed themselves in science and who regard the proper study of philosophy to be the fundamental nature of humankind. I do not know why this should be, though I can speculate on one possible source. We know that Westerners are constantly building causal models of the world. In fact, the children of Japanese who are living in the United States for business reasons are often regarded by American teachers as having weak powers of analysis because they do not build such causal models. One consequence of building explicit models is the element of surprise. The models lead to predictions that turn out to be wrong. This makes a person eager to get more accurate views—and more curious.

None of the habits of mind that are more characteristic of Easterners pose insurmountable obstacles to scientific excellence. The practice of science encourages mental patterns I have labeled as Western advantages, and the more steeped in scientific culture that Easterners become, the more natural will scientific habits of mind become. And Easterners may well be able to shape their distinctive habits of mind in ways that will provide advantages for scientific inquiry. Quantum theory in physics rests on contradictions that are anathema to the Western mind but congenial to the Eastern mind. Nils Bohr credited his deep knowledge of Eastern philosophy with his ability to generate quantum hypotheses.

For the time being, Westerners’ advantage in science may be their ace in the hole in their friendly competition with the East. But don’t count on the advantage lasting for long. Until fairly far into the last century, European scientists were puzzled by the failure of Americans to produce much science of note.