Chapter 1

Biophysical Chemistry of Physiological Solutions

Chapter Outline

III. Structure and Properties of Water

IV. Interactions Between Water and Ions

VII. Solute Transport: Basic Definitions

VIII. Measurement of Electrolytes and Membrane Potential

I Summary

This chapter describes the hydrogen-bonded structure of liquid water and its dipolar and dielectric properties. In salt solutions, water exhibits three regions of structure: oriented dipoles near ions; an intermediate structure-breaking region; and flickering clusters with short-range order characteristic of ice. Electrostatic interactions between ions and water based on Coulomb’s law account for the enthalpy of hydration, as well as for the sequence of ionic mobilities of the hydrated alkali cations. Salts and non-electrolytes dissolve in cell water with nearly the same solubility and activity as in extracellular water; even the viscosities are similar. Protons in solution are hydrogen-bonded to water to form H3O+, which is further hydrated due to electrostatic forces. Protons migrate through water by a Grotthus chain mechanism; in contrast, other hydrated ions migrate through water as hard spheres that interact with water dipoles according to the ionic radius and charge. Non-specific ion–ion interactions reduce the activity coefficients of ions, as described by the Debye–Hückel theory, which conceptualizes a central ion surrounded by a cloud of counterions with smeared charge. Selective interactions of ions with sites on enzymes or on channel proteins occur in certain predictable specific patterns (Eisenman sequences) that depend on the energy of interaction between the ions and water dipoles, relative to that between ions and their binding sites.

All of the solutes in a cell contribute to the free energy of the intracellular solution. The Gibbs equation, which is derived in the Appendix by combining the first and second laws of thermodynamics, enables estimation of the changes in free energy when solutes cross cell membranes. The change in free energy is zero at equilibrium and negative for spontaneous processes. Solutes will redistribute until the electrochemical potential is the same in every compartment to which that solute has access. The Nernst equation (see Appendix), which follows from the Gibbs equation, relates the ratio of intracellular to extracellular ion concentrations at equilibrium to the membrane potential, and can be used to test whether a solute is in electrochemical equilibrium across a cell membrane.

II Introduction

All living cells contain proteins, salts and water enclosed in membrane-bounded compartments. These biochemical and ionic cellular constituents, along with a set of genes, enzymes, substrates, and metabolic intermediates, function to maintain cellular homeostasis and enable cells to replicate and to perform chemical, mechanical and electrical work. Homeostasis, a term introduced by the physiologist Walter Cannon in The Wisdom of the Body (1932), means that certain parameters, including cellular volume, intracellular pH, the transmembrane electrical potential and intracellular concentrations of salts are maintained relatively constant in resting cells. Cellular homeostasis depends on a relative constancy of the extracellular fluids that bathe cells. The extracellular fluid compartment was termed the milieu intérieur, or internal environment, by Claude Bernard, who recognized around 1865 that “La fixité du milieu intérieur est la condition de la vie libre”, that the constancy of the internal environment is the condition for independent life. In An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine (see 1949 translation), Bernard wrote that “only in the physico-chemical conditions of the inner environment can we find the causation of the external phenomena of life”. The development of cell physiology has been greatly influenced by the Bernard–Cannon theory of physical-chemical homeostasis.

Biophysical chemistry concerns the application of the concepts and methods of physical chemistry to the study of biological systems. Physical chemistry includes such physiologically relevant subjects as thermodynamics, chemical equilibria and reaction kinetics, solutions and electrochemistry, properties and kinetic theory of gases, transport processes, surface phenomena and molecular structure and spectroscopy. Throughout this book, it is seen that many cellular physiological phenomena are best understood with a rigorous and comprehensive understanding of physical chemistry. During the past 65 years, outstanding monographs on biophysical chemistry have been available: Höber (1945), Edsall and Wyman (1958), Tanford (1961), Cantor and Schimmel (1980), Silver (1985), Bergethon and Simons (1990), and Weiss (1996). To help the reader begin to understand how cellular homeostasis is achieved, this chapter will introduce some of the conceptual underpinnings of cell physiology by describing certain physicochemical properties of water and electrolytes that are relevant for understanding living cells.

III Structure and Properties of Water

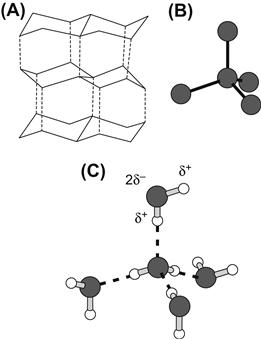

Biological cells contain a large amount of water, ranging from 0.66 g H2O/g cells in human red blood cells to around 0.8 g H2O/g tissue in skeletal muscle. The amount of water in cells is determined by osmosis. Liquid water is a highly polar solvent, with a structure stabilized by extensive intermolecular hydrogen bonds (Fig. 1.1). The hydrogen bonds between adjacent water molecules are linear (O–H···O) but are able to bend by about 10°. From x-ray diffraction studies of ice crystals, it is known that each of the two covalent O–H bonds in water is 1 Å in length, that each of the two hydrogen bonds is about 1.8 Å in length and that these occur around each oxygen atom at angles of 104°30′ in a tetrahedral array.

FIGURE 1.1 Hydrogen bonds in ice and liquid water. (A) Crystal structure of ice, showing the puckered hexagonal rings of oxygen atoms. (B) Each oxygen atom is connected to four others in a tetrahedron. (C) The linear hydrogen bonds are indicated by dotted lines between adjacent water molecules (O–H O). Two covalent bonds (O–H), indicated by solid lines, and two hydrogen bonds occur around each oxygen atom in a tetrahedral array. The partial charge separation of the O–H dipoles is indicated on the upper water molecule.

The energy required to break hydrogen bonds in liquid water is 5 to 7 kcal/mol, much less than the 109.7 kcal/mol required to break the covalent O–H bond. A calorie is a unit of work equal to 4.18 J in the SI system of units, where 1 joule (J) equals 1 Newton·meter. The newton (N = k·gm/s2) is the unit of force in the International System of Units (SI); the dyne (dyn = g·cm/s2) is the corresponding unit of force in the older cgs system (1 N = 105 dyn). Recall that, according to Newton’s first law, the force (F) is mass times acceleration and that work is defined as force times distance. Because of the strength of hydrogen bonds, liquid water has unique physicochemical properties, including a high boiling point (100°C), a high molar heat capacity (18 cal/mol·K), a high molar heat of vaporization (9.7 kcal/mol at 1 atm) and a high surface tension (72.75 dyn/cm). As discussed by Bergethon and Simons (1990), all of these thermodynamic parameters are considerably higher for H2O than for the analogous compound H2S, which boils at −59.6°C. The outer electrons of the S atom shield its nuclear charge and reduce its electronegativity, making the S–H bond weaker, longer and less polar than the O–H bond. Also, the bond angle of H2S is only 92°20′, an angle that does not form a tetrahedral array and thus H2S does not form a hydrogen bonded network like water.

The extensive intermolecular association in liquid water is due to the geometry of the water molecule and also to its strong permanent dipole moment. Water molecules have no net charge, yet possess permanent charge separation along each of the two O–H bonds. Since oxygen is more electronegative than hydrogen, its electron density is preferentially greater. Oxygen thus acquires a partial negative charge (δ−), leaving the hydrogens with a partial positive charge (δ+) (see Fig. 1.1C). The magnitude of the dipole moment (μ) of a chemical bond is computed as the product of the separated charge (q) at either end, and the distance (d) between the centers of separated charge (μ = qd). The dipole moment of a molecule is the vector sum of the dipole moments of each bond. For water in the gaseous phase, the dipole moment is 1.85 debye, where 1 debye = 10−18 esu·cm. One esu (electrostatic unit), or stat-coulomb, equals 3.336 × 10−10 C, the coulomb (C) being a unit of electric charge. In liquid water, the dipole moment becomes even larger (2.5 debye) due to association with other water molecules. In comparison, the linear molecule carbon dioxide (O=C=O) also has a separation of charge, with a partial negative charge on each oxygen atom and a partial positive charge on the carbon atom. In this case, the oppositely directed dipole moments of the two C=O bonds sum to a zero dipole moment for the CO2 molecule. In H2S, the S–H bond has a smaller dipole moment (1.1 debye) than the O–H bond in water because sulfur is less electronegative than oxygen. Electrostatic attractions between opposite charges in adjacent water dipoles stabilize the hydrogen-bonded structure of liquid water.

Water strongly affects the forces between ions in solution by virtue of its high dielectric constant. The dielectric constant (ε) of a medium known as a dielectric is defined as the ratio of the coulombic force (Fcoul) between two charges in a vacuum to the actual force (F) between the same two charges in the dielectric medium.

In a vacuum, the coulombic force, Fcoul (newtons, N), between two ions with charges q+ and q− (C) separated by a distance d (meters, m) is given by Coulomb’s law:

where ε0 is the permittivity constant (8.854 ×

× 10−12C2/N m2). Coulomb’s law states that the force between two point charges is directly proportional to the magnitude of each charge and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the charges. Substituting Fcoul into the above expression and rearranging yields the following:

10−12C2/N m2). Coulomb’s law states that the force between two point charges is directly proportional to the magnitude of each charge and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the charges. Substituting Fcoul into the above expression and rearranging yields the following:

The dielectric constant of a vacuum is unity and that of air is close to unity (εair = 1.00054). Increasing the dielectric constant of the solvent decreases the attractive force between oppositely charged ions. The force felt by a distant ion is reduced in a dielectric medium, such as water, as compared with a vacuum, because part of the interaction energy is spent aligning the intervening water dipoles and distorting their polarizable electron clouds. The dielectric constant of water at 25°C is 78.5, much greater than methanol (ε = 32.6), ethanol (24.0) or methane (1.7). In liquid water, the high dielectric constant weakens the coulombic attractive forces between oppositely charged particles and thus promotes dissociation and ionization of salts.

Although the thermodynamic properties of liquid water are explicable in terms of extensive hydrogen-bonding, the actual structure of water is complex. In the flickering cluster model, groups of 50–70 water molecules, resembling a slightly expanded broken piece of the ice lattice (icebergs), are continuously associating and dissociating on a picosecond time scale. This dynamic model contrasts with the extended order of solid ice. At a given instant, some water molecules are unattached to the clusters and are located in the interstitial regions of the network, but may attach and detach as the clusters continuously form and break down. Other theories treat water as a mixture of distinct states, or as a continuum of states, with considerable short-range order, characteristic of the crystalline lattice of ice.

Despite these uncertainties regarding the structure of liquid water and the influence of macromolecules on its properties in cells, the ability of water to act as a solvent inside cells closely resembles that of extracellular water. Thus, a variety of permeant, hydrophilic, non-metabolized non-electrolytes distribute at equilibrium across human red blood cell membranes with ratios of intracellular to extracellular concentrations that deviate from unity by less than 10% (Gary-Bobo, 1967). In mouse diaphragm muscle, Miller (1974) found that several alcohols, diols and monosaccharides exhibit distribution ratios within 2% of unity, whereas certain other sugars appear to be excluded from membrane-bounded intracellular compartments. The amount of solute that dissolves at equilibrium is also nearly normal in water that is constrained in gels, which are cross-linked networks of fibrous macromolecules. The diffusion of solutes within gels, however, may be hindered by collisions and interactions with the macromolecules and by the tortuosity of the diffusion paths.

Viscosity, another property of water, contributes to the resistance to flow. A fluid with a greater viscosity exhibits less flow under the influence of a given pressure gradient than a fluid with a lesser viscosity. For example, molasses, a concentrated sugar solution, is much more viscous than pure water. During laminar flow, a frictional force develops between adjacent layers (laminae) in the fluid and this force impedes the sliding of one lamina past its neighbor. In a Newtonian fluid, the frictional force per unit area, or shear stress (τ, dyn/cm2), is proportional to the velocity gradient, or rate of strain (dv/dy, s−1) between laminae,

where the viscosity (η) is the proportionality constant with units of poise (=1 dyn s/cm2), named after Poiseuille. The viscosity of H2O at 20.3°C is 0.01 poise, or 1 centipoise (cp). In cultured fibroblasts, the fluid-phase cytoplasmic viscosity, as determined from rotational motions of fluorescent probes on a picosecond time scale, is only 1.2–1.4 times that of pure water (Fushimi and Verkman, 1991). Fluorescence studies also show that the viscosity is the same in the cytoplasm and nucleoplasm and is unaffected by large decreases in cell volume or by disruption of the cytoskeleton with cytochalasin B. The fluid-phase viscosity, as determined from fluorophore rotational motions, is not nearly as affected by macromolecules as is the bulk viscosity and it thus provides a more accurate view of the physical state of the aqueous domain of the cytoplasm. These and other studies (e.g. Schwan and Foster, 1977; Horowitz and Miller, 1984) set limits on the extent to which the physicochemical properties of intracellular water differ from those of extracellular water.

IV Interactions Between Water and Ions

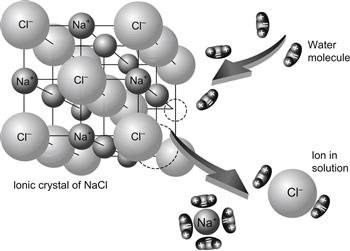

Ions in solution behave as charged, hard spheres that interact with and orient water dipoles. When crystals of sodium chloride are dissolved in water, the electrostatic attractive forces between water dipoles and ions in the crystal lattice overcome the inter-ionic attractive forces between oppositely charged ions in the crystal. The dissociated ions then acquire the freedom of translational motion as they diffuse into the solution accompanied by a layer of tightly associated hydration water (Fig. 1.2). Ion is the Greek word for “wanderer”. The strength of the attraction between ions and water dipoles depends to a large extent on the ionic charge and radius. For the alkali metal cations, the force of attraction and the energy of interaction of ions with water, decreases according to the following series: Li+> Na+>

Na+> K+>

K+> Rb+>

Rb+> Cs+.

Cs+.

FIGURE 1.2 Dissociation of NaCl in water into hydrated Na+ and Cl− ions.

Li+, being the smallest of the alkali metal cations, has the strongest interaction with water because its positively charged nucleus can approach most closely to the negative side of neighboring water dipoles. As the ionic radius increases with increasing atomic number in the alkali metal series, the filled outer shells of electrons effectively shield the cationic charge and reduce the distance of closest approach to water molecules. The smallest ion thus acquires the greatest degree of hydration and has the largest hydrated ionic radius.

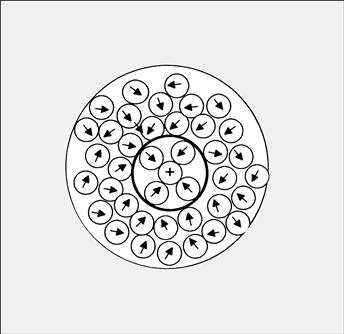

According to Frank and Wen (1957), the orienting influence of ions on water dipoles results in three regions of water structure (Fig. 1.3). The electric field of an ion is sufficiently strong to remove water dipoles from the bulk water clusters and to attract to itself the oppositely charged ends of from one to five water dipoles. A certain number of these water dipoles, called the hydration number, then become trapped and oriented in the ion’s electric field. The inner hydration shell includes water molecules that are aligned by the force field and in direct contact with the ion, 5 ±

± 1 for Li+, 4

1 for Li+, 4 ±

± 1 for Na+, 3

1 for Na+, 3 ±

± 2 for K+ and Rb+, 4

2 for K+ and Rb+, 4 ±

± 1 for F−, 2

1 for F−, 2 ±

± 1 for Cl− and Br− and 1

1 for Cl− and Br− and 1 ±

± 1 for I−. Thus, in physiological saline at 0.15 M NaCl in water (55.5 M), about 1.6% (=100

1 for I−. Thus, in physiological saline at 0.15 M NaCl in water (55.5 M), about 1.6% (=100 ×

× 0.15

0.15 ×

× 6/55.5) of the water is located in the inner hydration shells of Na+ and of Cl−. Water in the inner hydration shells of Na+, K+ and Ca2+ rapidly exchanges with bulk water on a nanosecond time scale but, in contrast, the smaller divalent cation Mg2+, with its high charge density, is some four orders of magnitude slower in exchanging its inner hydration water. The inner hydration sheath of water molecules moves together with the ion as a distinct and single kinetic entity.

6/55.5) of the water is located in the inner hydration shells of Na+ and of Cl−. Water in the inner hydration shells of Na+, K+ and Ca2+ rapidly exchanges with bulk water on a nanosecond time scale but, in contrast, the smaller divalent cation Mg2+, with its high charge density, is some four orders of magnitude slower in exchanging its inner hydration water. The inner hydration sheath of water molecules moves together with the ion as a distinct and single kinetic entity.

FIGURE 1.3 Three regions of water structure near an ion. A central cation is shown with a primary hydration shell of four oriented water dipoles, surrounded by a partially oriented secondary sheath. The gray region indicates the hydrogen-bonded structure of the bulk water.

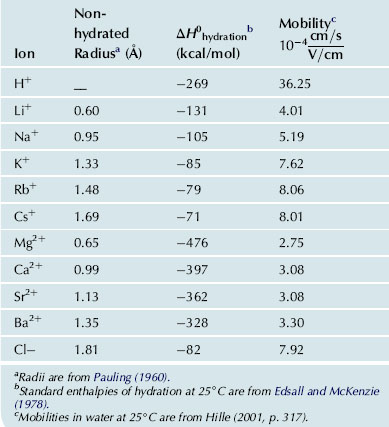

The mobilities of the alkali cations in water decrease as the non-hydrated ionic radius decreases, but as the hydrated ionic radius increases (Table 1.1; for discussion, see Hille, 2001). The ionic mobility (u) is defined as the proportionality constant that relates the velocity (v) of ionic migration to the force exerted by an external electric field E (v = u·E); in other words, mobility is the velocity per unit electric field. Farther away from the ion, where the ion’s electric field falls towards zero, water retains the structure of bulk water. In the region between the inner hydration sheath and the bulk water, the orienting influences of the ion and the bulk water network tend to compete and to disrupt the structure of water. In this intermediate structure-breaking region, the water dipoles are partially oriented toward the central ion, yet do not migrate with the ion, and they join only infrequently with the hydrogen-bonded clusters of the bulk water. If the net effect of an ion is to disorganize more water in the intermediate region than is found in the primary hydration shell, then the ion is termed a structure-breaker. Conversely, water may form a variety of hydrogen-bonded clathrate structures around apolar protein side chains, whose action resembles that of the class of solutes termed structure-makers (see Klotz, 1970, for review).

TABLE 1.1. Radii, Enthalpies of Hydration and Mobilities of Selected Ions

The enthalpy of hydration of an ion is a measure of the strength of the interaction between ions and water and is defined as the increase in enthalpy when one mole of free ion in a vacuum is dissolved in a large quantity of water. The enthalpy of hydration may be estimated from the heat released upon dissolving salts in water, usually less than 10 kcal/mol, taking into account the energy needed to dissociate the salt crystal and then to hydrate the ions. The enthalpy of hydration may be calculated using electrostatic theory. Accurate results are obtained if water is considered to be an electric quadrupole with four centers of charge, two partial positive charges near the hydrogen nuclei and two partial negative charges on the non-bonded electron orbitals near the oxygen nucleus. A further improvement in the calculated enthalpy of hydration is obtained when the polarizability (α) of the water dipole by the ion is taken into account. The electric field of the ion distorts the electron cloud of the hydration water along its permanent dipole axis, thus inducing an additional increment of charge separation and increasing the dipole moment. For small fields, this induced dipole moment (μind) is proportional to the electric field strength (E) and the constant of proportionality is the polarizability (μind =

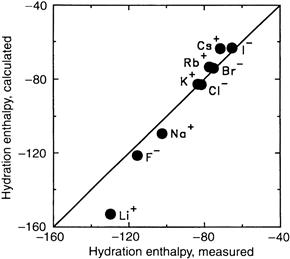

= α·E). In Fig. 1.4, the measured enthalpies of hydration for alkali metal cations and halides are compared with calculated values; the impressive agreement demonstrates the primary importance of electrostatic forces in determining the solvation of ions in water. The enthalpy of hydration for the smallest alkali metal cation Li+ is quite large at −131 kcal/mol. With increasing ionic radius, the enthalpy falls progressively for Na+, K+ and Rb+, reaching −71 kcal/mol for Cs+, the largest non-hydrated but smallest hydrated ion in the series (see Table 1.1). For the divalent, alkaline earth metal ions Mg2+ and Ca2+, the enthalpies of hydration also follow the ionic radius but are considerably larger at −476 kcal/mol and −397 kcal/mol, respectively. As pointed out by Hille (2001), the magnitude of ionic hydration enthalpies approximates the cohesive strength of the ionic bonds in a crystalline salt lattice.

α·E). In Fig. 1.4, the measured enthalpies of hydration for alkali metal cations and halides are compared with calculated values; the impressive agreement demonstrates the primary importance of electrostatic forces in determining the solvation of ions in water. The enthalpy of hydration for the smallest alkali metal cation Li+ is quite large at −131 kcal/mol. With increasing ionic radius, the enthalpy falls progressively for Na+, K+ and Rb+, reaching −71 kcal/mol for Cs+, the largest non-hydrated but smallest hydrated ion in the series (see Table 1.1). For the divalent, alkaline earth metal ions Mg2+ and Ca2+, the enthalpies of hydration also follow the ionic radius but are considerably larger at −476 kcal/mol and −397 kcal/mol, respectively. As pointed out by Hille (2001), the magnitude of ionic hydration enthalpies approximates the cohesive strength of the ionic bonds in a crystalline salt lattice.

FIGURE 1.4 Comparison of measured enthalpies of hydration of alkali metal cations and halides in water (abscissa), with those calculated (ordinate) taking into account the Born charging energy, ion-dipole interactions, ion-quadrupole interactions and ion-induced dipole interactions (data from Bockris and Reddy, 1970, p. 107).

Physical chemical analyses show that, in small spaces that restrict the formation of tetrahedral water clusters, the dielectric constant will be reduced and electrostatic forces between ions will then be correspondingly increased. In the primary hydration shell of ions, the oriented water is polarizable but cannot be reoriented by applied fields and so the dielectric constant is reduced from its bulk value of 78 to a value of about 6, with intermediate values in the partially oriented structure-breaking region between the primary hydration shell and the bulk water. For this reason, the dielectric constant of a solution decreases with increasing salt concentration but, in protein-free solutions at physiological salt concentrations, the extent of the decrease is small due to the small fraction of hydration water.

V Protons in Solution

The hydrogen-bonded structure of liquid water also contributes to high proton mobility by a mechanism that differs fundamentally from the migration of other hydrated ions. The proton is a highly reactive, positively-charged hydrogen nucleus, devoid of electrons. Whereas ions with electron shells typically have diameters in angstroms, the diameter of the proton is only about 10−5 Å. With such a small size, the proton has a strong attraction to electrons, as indicated by the high ionization energy of 323 kcal/mol needed to remove an electron from a hydrogen atom to form a proton. By comparison, the ionization energies for the alkali cations decrease with increasing atomic number in the series as follows:

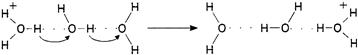

As more filled electron shells separate and shield the outer shell from the positively charged atomic nucleus, it becomes easier to form a cation by removing an electron. The high affinity of the proton for electrons, and its small size, explain its tendency to form hydrogen bonds with the unshared electrons of oxygen in water. Infrared spectra indicate that protons in solution exist predominantly in the form of hydronium ions H3O+. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data are consistent with a flattened trigonal pyramidal structure, with O–H bond lengths of 1.02 Å and H–O–H bond angles of 115°, a structure resembling that of NH3 but with a radius similar to that of K+. The free energy of formation of H3O+ from H2O and H+ is about −170 kcal/mol, which corresponds to a hypothetical concentration of free protons in solution at room temperature of about 10−150 M – “about as zero as one can get” say Bockris and Reddy (1970). The heat of hydration of H3O+ is an additional −90 kcal/mol. The change in the density of water with temperature is consistent with the hydration of H3O+ with an additional three water molecules, forming the tetrahedral cluster H9O4+ (Bockris and Reddy, 1970). The proton mobility in water is 36×10−4 cm2/s·V, much slower than expected on the basis of hydrodynamic theory if free protons were to carry the current, but curiously about seven times as fast as expected if H3O+ migrates like K+. The abnormally high proton mobility in water (and also in ice) is consistent with a Grotthus chain mechanism (Fig. 1.5) in which the successive breakage and formation of hydrogen bonds, accompanied by proton jumps between neighboring water molecules, effectively results in the passage of H3O+ along a chain. This transport process is rate-limited by the time needed for each successive acceptor water molecule to rotate and reorient its non-bonded orbital into a suitable position to accept the donated proton. The Grotthus mechanism accounts for about 80% of proton mobility, with the remaining 20% due to H3O+ itself, as a single kinetic entity, undergoing a translational migratory movement through the solvent like other ions.

FIGURE 1.5 Grotthus chain mechanism for proton mobility in water.

VI Interactions Between Ions

Interactions between ions may be weak or highly selective. Ions in solution attract ions of the opposite charge, in accordance with Coulomb’s law. Since the long-range attractive forces are inversely proportional to the square of the distance between charges, the interaction energies are greater in more concentrated solutions. In a uni-univalent salt solution, defined as having monovalent cations and anions, of concentration c (mol/L), the average distance (d, angstroms or Å) between any two ions is given by:

where NA is Avogadro’s number (6.023×1023). The factor 2 is included because the anions and cations are both counted and the factor 1027 is Å3/L. For 0.15 M NaCl, the average distance between Na+ and the nearest Cl− is 17.7 Å, at which range coulombic forces are highly significant. At pH 7.4, where the concentration of “protons” (really hydronium ions) is only 40 nM, the average distance between “protons” is 0.28 μm.

Attractive ion–ion interactions are stabilizing and they lower the chemical potential of an ion from its value in an ideal, infinitely-dilute solution. The activity (a) of an ion is defined in terms of its chemical potential (μ) as follows:

where μ0(T, P) is the standard-state chemical potential, or the chemical potential when the activity is 1. Increases in chemical activity increase the chemical potential. The chemical potential of a solute in an ideal dilute solution, where the activity equals the chemical concentration (c), is:

In order to describe the properties of more concentrated non-ideal solutions, G.N. Lewis introduced the activity coefficient (γ), such that the activity is the product of the concentration (c) and the activity coefficient (a =

= γ·c). The chemical potential of an ion in a non-ideal solution is:

γ·c). The chemical potential of an ion in a non-ideal solution is:

where the term RT ln γ includes the effect of ion–ion interactions on the chemical potential.

When a salt (c+c−) is added to water, the cations and anions, at concentrations c+ and c− respectively, both contribute to the free energy of the solution. The chemical potentials of the cations and anions (μ+ and μ−, respectively) are given by:

Adding these two expressions and taking the average, gives:

The mean ionic activity coefficient γ± is defined as:

Mean ionic activity coefficients of salts have been estimated theoretically by the Debye–Hückel theory, which supposes that central ions attract oppositely-charged ions (or counterions) in a diffuse and structureless ion cloud (or atmosphere). The forces of coulombic attraction between the central ion and its cloud of counterions are opposed by the randomizing influence of the thermal motion of the ions. In dilute solutions, in which the theory treats central ions as point charges relative to the size of the ion cloud, the mean ionic activity coefficient (γ±) for salt ions with charges z+ and z−, is given by the limiting law as follows:

where I is the ionic strength, defined as:

The constant A, which equals 0.5108 kg1/2·mol−1/2 is given in terms of B, which equals 0.3287 × 108 kg1/2·mol−1/2·cm−1, both at 25°C, as follows:

where NA is Avogadro’s number (6.023×1023 ions/mol), e0 is the charge on an electron (4.80×10−10 statcoul =

= 1.60 × 10−19 C), ε is the dielectric constant, R is the gas constant (8.32 J/mol·K), T is the absolute temperature (K) and k (=R/NA) is Boltzmann’s constant (1.38 × 10−23 J/K).

1.60 × 10−19 C), ε is the dielectric constant, R is the gas constant (8.32 J/mol·K), T is the absolute temperature (K) and k (=R/NA) is Boltzmann’s constant (1.38 × 10−23 J/K).

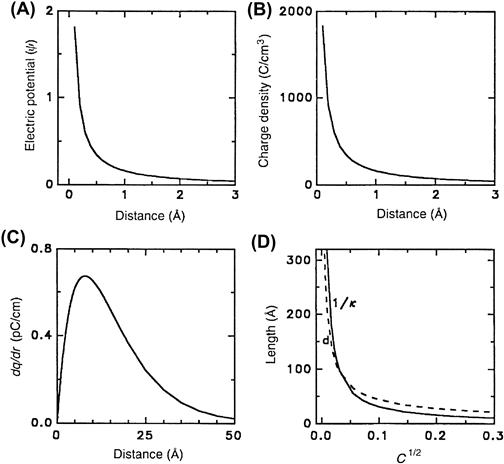

The derivation of the Debye–Hückel limiting law (see Bockris and Reddy, 1970) computes the spherically symmetric electric field around an ion, leading to an expression relating the charge density (ρr) of the ionic cloud to the electrostatic potential (ψr) at a distance r from the central point charge. The counterions, at concentration ni for ionic species i at a distance r from the central ion, are considered to distribute in the electric field according to a Boltzmann distribution:

where ni0 is the bulk ion concentration (ions/L). By linearizing the Boltzmann equation, using a Taylor series expansion and retaining only the first two terms, which assumes that zie0 ψr«kT, a resulting expression shows how the electrostatic potential ψ decreases as a function of distance (r) from the central ion (Fig. 1.6A):

where κ is given by:

The charge density (ρr) of the ionic cloud also decreases with increasing distance from the central ion (see Fig. 1.6B) according to:

The amount of charge dq contained in a concentric spherical shell of thickness dr located at a distance r from the central ion (see Fig. 1.6C) is given by:

Furthermore, the maximum amount of charge contained in such a spherical shell occurs at a distance κ−1, known as the Debye length, which defines the effective radius of the counterion atmosphere. It can also be shown that the Debye length is the distance away from the central ion where an ion of equal and opposite charge would contribute to the electrostatic field by an amount equivalent to that of the dispersed cloud of counterions (Bockris and Reddy, 1970). The Debye length decreases as the ionic concentration increases (see Fig. 1.6D).

FIGURE 1.6 Debye–Hückel theory. (A) Electrostatic potential (ψ), (B) charge density (ρ) of the counterion cloud and (C) the charge (dq) enclosed in a spherical shell of thickness (dr), each calculated and plotted versus distance d from the central ion. (D) Debye length κ−1 (solid line) and average distance d between ions (dashed line) versus square root of ion concentration.

The Debye–Hückel limiting law predicts activity coefficients accurately only to concentrations of about 0.01 M. In more concentrated solutions, the finite radius (a, in cm) of the ion is taken into account in the extended Debye–Hückel equation, given by:

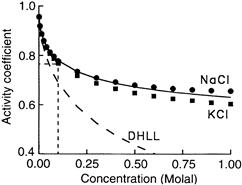

where the constants A and B are still 0.5108 kg1/2 mol−1/2 and 0.3287×108 kg1/2 mol−1/2 cm−1, respectively, for water at 25°C. The ion-size parameter (a) is adjustable, but reasonable values extend the range of concentrations for which the Debye–Hückel theory accurately predicts ionic activity coefficients (Fig. 1.7).

FIGURE 1.7 Activity coefficients of NaCl (circles) and KCl (squares). (Data are fromRobinson and Stokes (1959).) The dashed curve represents the prediction of the Debye–Hückel limiting law. The solid line represents the prediction of the extended Debye–Hückel equation with an ion size parameter a of 4.7 Å. The dashed vertical line indicates that at 0.1 M, the activity coefficients of NaCl and KCl are 0.77 and 0.76, respectively.

At still higher salt concentrations above about 0.7 M, the activity coefficient stops decreasing and instead begins to increase with increasing salt concentration. This behavior has been explained by the increasing fraction of hydration water, which both reduces the amount of free water in the solution and raises the effective concentration and, therefore, the activity, of the dissolved ions. Corrections for hydration enable prediction of the activity coefficient as a function of salt concentration over the full range of salt concentrations reaching to several molar. A related effect is that, in concentrated protein solutions, a certain shell of volume known as excluded volume around each protein is unavailable for solutes because the center of the solutes with their own finite size can only approach to within one solute radius of the protein surface. The fraction of excluded volume increases with increasing protein concentration and with increasing radius of the solutes which themselves may be proteins with enzymatic or regulatory activities. Such macromolecular crowding can dramatically increase activities of proteins in concentrated solutions.

The activity coefficients calculated by the Debye–Hückel theory indicate that the forces between ions in dilute solutions are weak and non-selective. The predicted activity coefficients depend on the ionic charge and the ionic strength of the solution and they are largely independent of the specific ion within, say, the alkali metal series. A very small degree of selectivity is introduced with the ion size parameter. The mean ionic activity coefficients for NaCl and KCl as a function of salt concentration are shown in Fig. 1.7. At 0.1 M concentrations, the activity coefficient of Na+ is 0.77, whereas those of K+ and Cl− are both 0.76. These relatively high activity coefficients correspond to ion–ion interaction energies of only about −0.3 kcal/mol (see Hille, 2001).

Agreement between theory and data, such as seen in Fig. 1.7 for the Debye–Hückel theory, does not necessarily imply the correctness of the theory, or of the model on which the theory is based. A fundamental criticism of the Debye–Hückel theory concerns the smeared charge model for the cloud of counterions (Frank and Thompson, 1960). Below a concentration of about 0.001 M, the Debye length κ−1 is greater than the average distance between ions in the solution (see Fig. 1.6D), in which case the counterions could reasonably appear as a cloud of smeared charge from the vantage point of the central ion. Above 0.001 M, however, the Debye length incongruously falls below the average distance between ions in the solution. Moreover, at only 0.01 M, just one ion is needed to account for 50% of the effect of the counterion cloud on the central ion, yet this ion must be smeared around the central ion in a cloud of spherically symmetric charge distribution located only 25 Å away from the central ion (Bockris and Reddy, 1970). Thus, well below physiological salt concentrations, the assumption of smeared charge in the Debye–Hückel theory is not in accord with the coarse-grained structure of salt solutions, despite the impressive ability of the theory to predict activity coefficients. A quasi-lattice approach to salt solutions minimizing the free energy using modern computational power would seem to be a preferable alternative (see Horvath, 1985, for references).

Intracellular solutions may be quite concentrated. The red-cell membrane and associated cytoskeleton enclose a viscous cytoplasmic solution of the oxygen-binding pigment hemoglobin at a concentration of 34 g/100 mL cells, corresponding to 5.2 mM, 7.3 millimolal, or 44 g Hb/100 g cell water. This concentration is near the threshold for gelation, but hemoglobin is one of the most soluble of all proteins and constitutes more than 98% of red-cell protein by mass. The hemoglobin α2β2 tetrameters have a molecular weight of 64 373 Da and are approximately spheroidal with dimensions of 65 × 55 Å×50 Å. In the interior of red blood cells, hemoglobin is nearly close-packed, with the distance between the surfaces of neighboring proteins averaging only about 20 Å. With the 86 carboxylates of aspartic and glutamic acids and with the 98 basic amino and amine groups of arginine, lysine and histidine per hemoglobin tetramer, the total cellular concentration of the titratable amino acids of human hemoglobin is around 0.9 M. Thus, hemoglobin contributes significantly, depending on intracellular pH, to a high intracellular ionic strength. Since the charged amino acids are located on the surface of hemoglobin and taking the radius of hemoglobin to be 28 Å, the average distance between charged sites is only about 7 Å. About 7600 water molecules per hemoglobin tetramer occupy the narrow interstices between the protein molecules. The hydration of hemoglobin in dilute solution is 0.2–0.3 g water/g Hb, representing about 15% of the intracellular water. When the tortuosity of the surface of soluble proteins is taken into account, as much as 30% of red-cell water could reside in the first monolayer around the protein surface.

To determine the mean ionic activities of the intracellular KCl and NaCl in the concentrated charged environment of human red blood cells, studies were conducted in which the red-cell membrane was rendered permeable to cations by exposure of the cells to the channel-forming antibiotic nystatin, thus allowing K+, Na+ and Cl− to reach Gibbs–Donnan equilibrium. In these experiments, sufficient extracellular sucrose was added to prevent cell swelling by balancing the colloid osmotic pressure of hemoglobin and other impermeant cell solutes. The mean ionic activity coefficient of KCl and NaCl in the concentrated intracellular hemoglobin solution was found to be within 2% of that in the extracellular solution (Freedman and Hoffman, 1979a). In view of the high intracellular ionic strength and the high volume fraction of cell water in direct contact with hemoglobin, it is both curious and remarkable that intracellular salts and non-electrolytes appear to behave as if in dilute solution. Either the intracellular solution is indeed like a dilute solution or, alternatively, the expected effect of protein–solvent interactions in altering the activity of intracellular solutes is offset by the effect of interactions between proteins and the solutes themselves.

Specific effects of small anions on the solubility, aggregation or denaturation of proteins often follow the Hofmeister (lyotropic) series in the following order of effectiveness:

The ions to the right of Cl− are referred to as chaotropic, since they tend to destabilize proteins (for review, see Collins and Washabaugh, 1985). Ions may also associate with sites on proteins, as exemplified by the binding to albumin of Ca2+ (Katz and Klotz, 1953), and of Cl− (Scatchard et al., 1957; see ch. 8 in Tanford, 1961). Certain enzymes, ion channels and membrane transport proteins interact with the alkali cations with a high degree of ionic selectivity. Considering the five alkali metal cations, there are 5! (=120) possible orders of selectivity that might arise. However, only 11 cationic selectivity orders commonly occur in chemical and biological systems, as listed in Table 1.2. Eisenman (1967) predicted these selectivity orders by calculating the ion-site interaction energies. If the field strength of a negatively-charged site is weak, then an associated ion remains hydrated. In this case, Cs+, having the smallest hydrated ionic radius, is favored (Sequence I) because it can approach most closely to the site and thus has the strongest coulombic force of attraction. If the field strength of the site is strong and the interaction energy between the ion and the site is stronger than the energy between the ion and water dipoles, then the ion is stripped of its associated water and becomes dehydrated. In this case, Li+, having the smallest non-hydrated ionic radius, becomes favored (sequence XI). With intermediate field strengths, ions partially dehydrate, giving rise to the intervening selectivity sequences. For example, K+ functions as a co-factor for the glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase, with the maximal catalytic velocity following Eisenman sequence IV. During in vitro protein synthesis, K+ maintains an active conformation of 50S ribosomal subunits that catalyze peptide bond formation following Eisenman sequence III. Other sequences are possible when the sites are assumed to be polarizable (for review, see Eisenman and Horn, 1983).

TABLE 1.2. Eisenman’s Selectivity Sequences for Binding of Alkali Cations to Negatively Charged Sites

| Highest field strength of site | |

| Li > Na > K > Rb > Cs | Sequence XI |

| Na > Li > K > Rb > Cs | Sequence X |

| Na > K > Li > Rb > Cs | Sequence IX |

| Na > K > Rb > Li > Cs | Sequence VIII |

| Na > K > Rb > Cs > Li | Sequence VII |

| K > Na > Rb > Cs > Li | Sequence VI |

| K > Rb > Na > Cs > Li | Sequence V |

| K > Rb > Cs > Na > Li | Sequence IV |

| Rb > K > Cs > Na > Li | Sequence III |

| Rb > Cs > K > Na > Li | Sequence II |

| Cs > Rb > K > Na > Li | Sequence I |

| Lowest field strength of site | |

VII Solute Transport: Basic Definitions

In the intracellular or extracellular solutions, a solute is said to be at equilibrium when its concentration is constant in time without requiring the continuous input of energy from metabolism or other sources. In human red blood cells, for example, Cl−, HCO3− and H+ are at thermodynamic equilibrium, i.e. they are passively distributed. A solute is said to be at steady-state when its concentration is constant in time, but is dependent on the continuous input of energy from metabolism or other sources. Active transport utilizes energy and results in steady-state distributions that represent a deviation from equilibrium. In biological cells, the concentrations of Na+, K+ and Ca2+ are at a steady-state. Their concentrations are constant in time, but are dependent on the continuous hydrolysis of ATP by the Na+-K+ pump (for review, see Glynn, 1985) and the Ca2+ pump. With isolated red cell membranes (“ghosts”), active transport of Na+ and K+ against their respective concentration gradients has been observed directly by measurements of net fluxes (Freedman, 1976). The active production and maintenance of ion concentration gradients by membrane pumps, such as the Na+, K+-ATPase and the Ca2+-ATPase, represent chemical work and electrical work done by the cell. The energy required for continuous pumping of Na+ by resting frog sartorius muscles has been estimated to represent some 14–20% of the energy available from the hydrolysis of ATP and the value is similar in red blood cells.

Passive transport is the movement of solutes toward a state of equilibrium. Passive transport of hydrophobic substances across cell membranes usually occurs directly by diffusion across the lipid bilayer. Passive transport of hydrophilic substances is usually mediated by specific membrane proteins via a process known as facilitated diffusion. Passive ion transport may occur through pores or ion channels under the influence of concentration gradients and electrical forces by a process known aselectrodiffusion. The passive flow of ionic currents down their concentration gradients through specific ion channel proteins constitutes negative work done by the cell. The changes in free energy associated with ion transport and the Nernst equilibrium equation are described in the Appendix.

VIII Measurement of Electrolytes and Membrane Potential

Ion concentrations in biological fluids may be expressed as millimoles per liter of solution (millimolar, or mM), or as millimoles per kilogram of water (millimolal). When a solution containing metallic ions is aspirated into a flame, each type of ion burns with a characteristic color, Na+ giving a yellow flame, K+ giving a violet flame and Ca2+ giving a red flame. In the technique of flame photometry, the intensity of the emitted light, in comparison with that produced by solutions containing known concentrations of ions, provides a convenient measure of ion concentration in extracellular fluids and in acid extracts of cells. With a uniform rate of aspiration, a flame photometer accurately measures the intensity of the emitted light, which is related linearly to the cation concentrations in suitably diluted standards and unknowns (see e.g. Funder and Wieth, 1966). Atomic absorption spectroscopy is an alternative technique that measures the light absorbed by ions during electronic excitation in a flame. Flame photometry and atomic absorption spectroscopy both measure total ionic concentrations in cell extracts irrespective of any intracellular compartmentation and they are sensitive in the millimolar range of cellular concentrations. K+, Na+, Ca2+ and other elements in single cells, or even in single cell organelles, may be measured by electron probe microanalysis, a technique that utilizes an electron beam to excite the emission of x-rays with energies characteristic of the various elements in cells.

The development of ion-specific glass microelectrodes by Eisenman (1967) and then of selective liquid ion exchange microelectrodes, made possible the direct determination of intracellular cation activities. Palmer and Civan (1977) found that for Na+, K+ and Cl− of Chironomus salivary gland cells, the ion activities are the same in the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments. In a related study, Palmer et al. (1978) found that during development of frog oocytes, the ratio of the cytoplasmic concentration of Na+ to K+ increases, while the corresponding ratio of ion activities decreases. This observation could reflect the development of yolk platelets and intracellular vesicles that contain ions at differing concentrations and activities than does the bulk cytoplasm. In frog skeletal muscle, the sarcoplasmic reticulum contains a solution enriched in calcium, whereas the ionic composition of the solution in the t-tubules is extracellular. The extracellular space, however, consists of the interstitial space between the muscle fibers as well as the vascular space; solutes leave these two extracellular compartments with differing rate constants, thus considerably complicating the interpretation of experiments that assess the rate of membrane transport with radioactive isotopes of Na+, K+ and other solutes (Neville, 1979; Neville and White, 1979).

To measure transient changes of intracellular Ca2+ in the micromolar and submicromolar range, fluorescent chelator dyes such as Quin-2, Fura-2, Indo-1 and Fluo-3 have been developed (Tsien, 1988). Quin-2, Fura-2, and Indo-1 are fluorescent analogs of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), which contains four carboxylate groups that specifically bind two divalent cations. EGTA is a non-fluorescent analog with a higher binding affinity for Ca2+ as compared with its affinity for Mg2+ and it is thus quite useful in experiments where the extracellular concentration of Ca2+ is systematically varied. Fluo-3 is a tetracarboxylate fluorescein analog that exhibits a shift in the emission spectrum upon binding Ca2+; in contrast, Fura-2 undergoes a shift in its excitation spectrum. By measuring the ratio of Fura-2 fluorescence upon excitation at two exciting wavelengths, changes in the concentration of Ca2+ may be monitored. The cells are incubated with a permeant ester form of the dye to enable the dye to permeate into cells; intracellular esterases then release the Ca2+-sensitive chromophore. With video microscopy of cells stained with fluorescent Ca2+ indicators, it is also possible to obtain time-resolved and spatially-resolved light microscopic images of the changes in intracellular Ca2+. Another fluorescent probe (SPQ), developed by Helsey and Verkman (1987), has been used to measure intracellular Cl− and to study its transport across cell membranes.

The transmembrane electrical potential is usually measured by means of open-tipped microelectrodes such as those developed and used by Ling and Gerard (1949) to obtain accurate and stable measurements of the membrane potential of frog skeletal muscle. With human red blood cells, stable potentials have not been achieved with microelectrodes. As an alternative technique, Hoffman and Laris (1974) utilized fluorescent cyanine dyes to monitor and measure red cell membrane potentials. Fluorescent cyanines, merocyanines, oxonols, sytryls, rhodamines and other dyes have since been used in numerous electrophysiological studies of red blood cells, neutrophils, platelets and other non-excitable cells and organelles that are too small for the use of microelectrodes (for review, see Freedman and Novak, 1989a). The equilibrium distribution of permeant, lipophilic, radioactively labeled ions such as triphenylmethylphosphonium (TPMP+) may also be used to assess the membrane potential using the Nernst equilibrium equation (see Freedman and Novak, 1989b).

Appendix: Thermodynamics of Membrane Transport

AI Free Energy

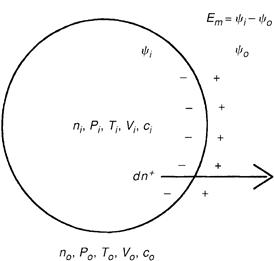

When ions cross cell membranes, changes in free energy are involved. Consider a membrane permeable only to cations separating two solutions of KCl of differing concentrations, ci and co, where the subscripts i and o represent the intracellular and extracellular compartments, respectively (Fig. 1A.1). If the intracellular concentration (ci) is greater than the extracellular concentration (co), then potassium will tend to diffuse out of the cell down its concentration gradient. When only a very slight amount of potassium crosses the membrane (which for this example is assumed to be impermeable to chloride), the separation of charge creates a transmembrane electrical potential (Em) that is negative inside, relative to outside. The resultant electrical force retards further efflux of potassium. An equilibrium is reached when the diffusion force favoring efflux of potassium exactly balances the electrical force, preventing efflux of potassium.

FIGURE 1A.1 Free energy of ion transport. A cell membrane separates the intracellular (subscript i) and the extracellular (subscript o). Each compartment is at pressure P and temperature T, has volume V and electrical potential ψ and contains solutes at concentration c. A free energy change is involved when dn+ moles of cation leave the cell. The membrane potential Em is ψi−ψo.

Prior to the attainment of equilibrium, the process of moving dn moles of K+ ions out of the cell from compartment i to compartment o involves a change in free energy (dG) of the system. According to the laws of thermodynamics, the process will occur spontaneously only if dG <

< 0 and the system will be at equilibrium if dG

0 and the system will be at equilibrium if dG =

= 0. Thus, in order to compute the change in free energy (dG), we need to review certain basic thermodynamic principles.

0. Thus, in order to compute the change in free energy (dG), we need to review certain basic thermodynamic principles.

The first law of thermodynamics, also known as the law of conservation of energy, states that for any system, the increase in energy (dE) is the gain in heat (dQ) minus the work (dW) done by the system:

For reversible processes, the second law of thermodynamics defines the change in entropy (dS) of a system in terms of the heat gained (dQ) and the absolute temperature (T) as follows:

Combining the first and second laws gives:

Since the difference in pressure (dP) between the internal and external solutions of animal cells is negligible, the work (dW) done by the system includes pressure–volume work, PdV, and electrical work, zF∈mdn, summed as follows:

where P is the pressure, V is the total volume of the system, z is the ionic valence (eq/mol), F is the Faraday constant (=96 490 C/eq) and dn is the number of moles of solute crossing the membrane and leaving the cell. The transmembrane electrical potential (∈m) is the difference in electrical potential (ψ, in volts or J/C), between the two compartments:

The electrical potential (ψ) represents the work done in moving a unit positive test charge from infinity to a point in the solution. Note that when the transmembrane electrical potential (∈m) is negative inside, the electrical work done by the system is negative whenever Na+ or K+ leave the cell, but positive when K+ or Na+ enter the cell, irrespective of the mechanism of transport.

According to the first and second laws, the change in energy (dE) of the system is:

For systems of variable chemical composition, the free energy (G) is by definition:

where the enthalpy (H) is defined as;

The chemical potential μj of the jth solute in the system at constant T, P, and nk is defined by:

where nj and nk are the number of moles of the jth and kth solutes, respectively. The chemical potential, also called the partial molar free energy, represents the incremental addition of free energy to the system upon incremental addition of a solute. All solutes contribute to the free energy of a solution. While the free energy itself is a parameter of state for the whole system, the chemical potential refers to a particular solute. The free energy is thus given by:

Differentiating yields:

Substituting the expression for dE given previously and simplifying yields a form of the Gibbs equation,

which states that the free energy of a system of variable chemical composition is a function of the temperature, the pressure and the number of moles of each component in the mixture, or G =

= G(T, P, nj). For processes that occur at constant temperature and pressure, where dT

G(T, P, nj). For processes that occur at constant temperature and pressure, where dT =

= dP

dP =

= 0, the Gibbs equation simplifies to:

0, the Gibbs equation simplifies to:

which states that the increase in free energy of a system is equal to the sum of the electrical work done on the system plus the total change in free energy due to changes in chemical composition. Furthermore, when the system is at equilibrium, dG must equal zero. The second law of thermodynamics also implies that the change in free energy (dG) is negative for all spontaneous processes. Thus, the first and second laws of thermodynamics, when combined with the definitions of free energy and enthalpy, result in the Gibbs equation, which is the fundamental equation for the estimation of free energy changes when water, ions, or other solutes cross cell membranes.

AII Nernst Equilibrium

The Nernst equation describes the relationship between voltage across a semipermeable membrane and the ion concentrations at equilibrium in the compartments adjacent to the membrane. The Nernst equation provides a simple method of testing whether or not a particular solute is at equilibrium.

Considering the example described in the previous section and using the Gibbs equation, the change in the free energy of the system that occurs when dn moles of K+ ions move from compartment i containing K+ at activity ai to compartment o containing K+ at activity ao is given by:

where the change in free energy has been summed for the two compartments. For this process, the decrease in the number of moles of solute inside the cell (−dni) equals the increase outside the cell (dno), so that both may be represented by dn:

and therefore

The chemical potential in each solution is:

For the system under consideration, the intracellular and extracellular standard-state chemical potentials are assumed to be identical:

and thus:

At equilibrium, dG =

= 0 and, since, dn

0 and, since, dn ≠

≠ 0 therefore

0 therefore

Rearranging yields the Nernst equation for a cationic concentration cell,

Converting the natural logarithm to base 10 yields:

The value of 2.303RT/F is 58.7 mV at 23°C and 61.5 mV at 37°C.

For charged solutes, the electrochemical potential (μj; =

= dG/dnj) of the jth solute is defined as the sum of a chemical and an electrical component. The electrical contribution to the electrochemical potential is zFψ and the chemical contribution is RT ln a.

dG/dnj) of the jth solute is defined as the sum of a chemical and an electrical component. The electrical contribution to the electrochemical potential is zFψ and the chemical contribution is RT ln a.

Note that a fundamental condition of equilibrium is that the difference in electrochemical potential between compartments i and o is zero. The electrochemical potential of the solute is the same in each compartment to which that solute has access.

The Nernst equation is independent of the mechanism of transport and is often used for ascertaining whether or not an intracellular ion is at electrochemical equilibrium. If so, then:

Another way of understanding the Nernst equation is that, at equilibrium, ions distribute across the membrane electric field in accordance with a Boltzmann distribution.

If z =

= 0, as for non-electrolytes, then ai

0, as for non-electrolytes, then ai =

= ao, and the activities of the solutes will be the same at equilibrium on both sides of the membrane, as was found to be nearly the case for the distribution of non-electrolytes across the membranes of human red blood cells (Gary Bobo, 1967). If z

ao, and the activities of the solutes will be the same at equilibrium on both sides of the membrane, as was found to be nearly the case for the distribution of non-electrolytes across the membranes of human red blood cells (Gary Bobo, 1967). If z ≠

≠ 0, as for electrolytes then, at equilibrium, each permeant monovalent ion will reach the same ratio of intracellular to extracellular activity. Such is the case for the passive distribution of Cl−, HCO3− and H+ in human red blood cells.

0, as for electrolytes then, at equilibrium, each permeant monovalent ion will reach the same ratio of intracellular to extracellular activity. Such is the case for the passive distribution of Cl−, HCO3− and H+ in human red blood cells.

In red blood cells, Na+, K+ and Ca2+ deviate from this ratio due to the action of the Na+-K+ pump and Ca2+ pump. In skeletal muscle, K+ and Cl− have Nernst equilibrium potentials that are close to the actual measured resting potential, while Na+ is far from equilibrium. In squid axons, the Nernst equilibrium potential for K+ is closest to the resting potential, Cl− is somewhat removed and, as in muscle and red blood cells, Na+ is far from equilibrium.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Bergethon PR, Simons ER. Biophysical Chemistry Molecules to Membranes. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1990.

2. Bernard C. An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine. [H.C. Green, translator] New York: Schuman; 1949.

3. Bockris JO’M, Reddy AKN. Modern Electrochemistry. Vol. (1) New York: Plenum Press; 1970.

4. Cannon WB. The Wisdom of the Body. New York: Norton; 1932.

5. Cantor CR, Schimmel PR. Biophysical Chemistry. Parts I, II, III San Francisco: W.H. Freeman; 1980.

6. Collins KD, Washabaugh MW. The Hofmeister effect and the behavior of water at interfaces. Q Rev Biophys. 1985;18:323–422.

7. Cooke R, Kuntz ID. The properties of water in biological systems. Ann Rev Biophys Bioeng. 1975;3:95–126.

8. Debye P. Polar Molecules. New York: Dover Publications; 1929.

9. Dick DAT. Osmotic properties of living cells. Internatl Rev Cytol. 1959;8:387–448.

10. Edsall JT, McKenzie HA. Water and proteins I The significance and structure of water; its interaction with electrolytes and nonelectrolytes. Adv Biophys. 1978;10:137–207.

11. Edsall JT, Wyman J. Physical Biochemistry. New York: Academic Press; 1958.

12. Eisenberg D, Kauzmann W. The Structure and Properties of Water. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1969.

13. Eisenman G. Glass Electrodes for Hydrogen and other Cations. New York: M. Dekker; 1967.

14. Eisenman G, Horn R. Ionic selectivity revisited: the role of kinetic and equilibrium processes in ion permeation through channels. J Membr Biol. 1983;76:197–225.

15. Frank HS, Thompson PT. A point of view on ion clouds. In: Hamer WJ, ed. The Structure of Electrolyte Solutions. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1960;:113–134.

16. Frank HS, Wen W-Y. Structural aspects of ion-solvent interaction in aqueous solutions: a suggested picture of water structure. Disc Faraday Soc. 1957;24:133–140.

17. Freedman JC. Partial restoration of sodium and potassium gradients by human erythrocyte membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;455:989–992.

18. Freedman JC, Hoffman JF. Ionic and osmotic equilibria of human red blood cells treated with nystatin. J Gen Physiol. 1979a;74:157–185.

19. Freedman JC, Novak TS. Optical measurement of membrane potentials of cells, organelles, and vesicles. Meth Enzymol. 1989a;172:102–122.

20. Freedman JC, Novak TS. Use of triphenylmethylphosphonium to measure membrane potentials in red blood cells. Meth Enzymol. 1989b;173:94–100.

21. Funder J, Wieth JO. Determination of sodium, potassium, and water in human red blood cells Elimination of sources of error in the development of a flame photometric method. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1966;18:151–166.

22. Fushimi K, Verkman AS. Low viscosity in the aqueous domain of cell cytoplasm measured by picosecond polarization microfluorimetry. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:719–725.

23. Gary-Bobo CM. Nonsolvent water in human erythrocytes and hemoglobin solutions. J Gen Physiol. 1967;50:2547–2564.

24. Glynn IM. The Na+, K+-transporting adenosine triphosphatase. In: Martonosi AN, ed. New York: Plenum Press; 1985;:35–114. The Enzymes of Biological Membranes. Vol. 3.

25. Heilbrunn LV. The Dynamics of Living Protoplasm. New York: Academic Press; 1956.

26. Helsey NP, Verkman AS. Membrane chloride transport measured using a chloride-sensitive fluorescent probe. Biochemistry. 1987;26:1215–1219.

27. Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3rd ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2001.

28. Höber R. Physical Chemistry of Cells and Tissues. Philadelphia: The Blakiston Company; 1945.

29. Hoffman JF, Laris PC. Determination of membrane potentials in human and Amphiuma red blood cells by means of a fluorescent probe. J Physiol (London). 1974;239:519–552.

30. Horowitz SB, Miller DS. Solvent properties of ground substance studied by cryomicrodissection and intracellular reference-phase techniques. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:172s–179s.

31. Horvath AL. Handbook of Aqueous Electrolyte Solutions Physical Properties, Estimation and Correlation Methods. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1985.

32. Katz S, Klotz IM. Interactions of calcium with serum albumin. Arch Biochem. 1953;44:351–361.

33. Klotz IM. Water: its fitness as a molecular environment. In: Bittar EE, ed. New York: Wiley; 1970;:93–122. Membranes and Ion Transport. Vol. 1.

34. Läuger P. Electrogenic Ion Pumps. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 1991.

35. Ling GN, Gerard RW. The normal membrane potential of frog sartorius fibers. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1949;34:383–396.

36. Miller C. Nonelectrolyte distribution in mouse diaphragm muscle I The pattern of nonelectrolyte distribution and reversal of the insulin effect. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;339:71–84.

37. Neville MC. The extracellular compartments of frog skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1979;288:45–70.

38. Neville MC, White S. Extracellular space of frog skeletal muscle in vivo and in vitro: relation to proton magnetic resonance relaxation times. J Physiol. 1979;288:71–83.

39. Palmer LG, Civan MM. Distribution of Na+, K+, and Cl− between nucleus and cytoplasm in Chironomus salivary gland cells. J Membr Biol. 1977;33:41–61.

40. Palmer LG, Century TJ, Civan MM. Activity coefficients of intracellular Na+ and K+ during development of frog oocytes. J Membr Biol. 1978;40:25–38.

41. Pauling L. The Nature of the Chemical Bond and the Structure of Molecules and Crystals; an Introduction to Modern Structural Chemistry. 3rd ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1960.

42. Robinson RA, Stokes RH. Electrolyte Solutions. 2nd ed. London: Butterworths; 1959.

43. Scatchard G, Coleman JS, Shen AL. Physical chemistry of protein solutions VII The binding of some small anions to serum albumin. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;79:12–20.

44. Schwan HP, Foster KR. Microwave dielectric properties of tissue Some comments on the rotational mobility of tissue water. Biophys J. 1977;17:193–197.

45. Silver BL. The Physical Chemistry of Membranes. Boston: Allen and Unwin; 1985.

46. Tanford C. Physical Chemistry of Macromolecules. New York: Wiley; 1961.

47. Tsien RY. Fluorescence measurement and photochemical manipulation of cytosolic free calcium. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:419–424.

48. Weiss TF. Cellular Biophysics, Vol 1: Transport, Vol 2: Electrical Properties. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 1996.