Chapter 8

Diffusion and Permeability

Chapter Outline

V. Diffusion Across a Membrane with Partitioning

VIII. Special Transport Processes

I Summary

This chapter describes diffusion of uncharged particles and charged ions across membranes with and without partitioning and provides the relevant equations that govern such diffusion. The relationship between the diffusion coefficient (D) and the permeability coefficient (P) is presented, as well as the factors that determine these coefficients. The dependence of P on the mobility of an ion through the membrane under a voltage gradient is also described. Electrochemical potential is defined and the interconversion between flux and current is presented. Finally, the Ussing flux ratio equation is presented and examples of its significance are given. Relating to this, the concept of potential energy wells and barriers is presented, describing the movement of an ion through an ion channel.

II Introduction

In order to understand the fundamentals of membrane transport, as well as the mechanisms for development of the electrical resting potential (RP) of cells, it is first necessary to consider the basic processes of diffusion and membrane permeability. Therefore, this chapter discusses fundamental principles that are utilized in subsequent chapters in this book.

Molecules of gases and liquids and dissolved solutes are continuously in motion. The velocities of individual molecules vary tremendously, as do their kinetic energies (in accordance with the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution). Diffusion is the process whereby particles in a gas or liquid tend to intermingle due to their spontaneous motion caused by thermal agitation. Any diffusing substance tends to move from regions of higher concentration to regions of lower concentration, until the substance is uniformly distributed at equilibrium. The molecules continue to move at equilibrium, but the net movement is zero. In the absence of convection, which refers to bulk flow of solvent, such as that caused by stirring, the movement of the molecules is by diffusion only. Diffusion occurs because of the random thermal motions of the molecules. Particles flow from a region of high concentration to one of low concentration. If a solution of high solute concentration is adjacent to one of low concentration, but separated by an imaginary plane, it is probable that more molecules per unit of time will be crossing the plane from the side of higher concentration to the side of lower concentration than in the opposite direction. There are fluxes (movements of molecules) in both directions (the unidirectional fluxes), but the net flux is from the side of higher concentration to the side of lower concentration.

Now, if the imaginary plane were replaced with a thin membrane permeable to the molecules, then the same situation would apply; the particles would diffuse from the side of higher concentration to the side of lower concentration across the membrane. In a living cell, it is usually assumed that the bulk solutions are relatively well mixed and diffusion of most substances through the cell membrane is much slower than that through a free solution. Therefore, diffusion through the membrane is the rate-limiting step. For simplicity, we assume that the solutions on either side are well stirred (although there may actually be unstirred layers near the membrane). We confine ourselves here to the diffusion of small molecules or ions across the cell membrane.

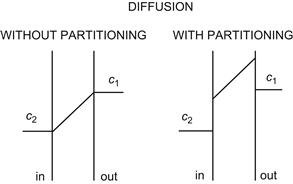

For thin membranes, we first consider the case of diffusion without partitioning, as illustrated in Fig. 8.1 (left), in which the diffusing molecule can freely enter the membrane. We will then introduce the effect of partitioning into the membrane, a process that involves a change of chemical potential upon entrance into the membrane phase, as illustrated in Fig. 8.1 (right). We disregard possible structural obstacles that may be a series of potential energy barriers within the membrane (Danielli, 1943).

FIGURE 8.1 Concentration gradients across the membrane during diffusion without partitioning (left) and with partitioning (right).

III Fick’s Law of Diffusion

The fundamental law describing diffusion was enunciated by Adolph E. Fick in 1855, who noted a similarity between diffusion of solutes and Fourier’s law describing the flow of heat in solids. Fick’s law of diffusion was deduced theoretically in 1860 by James C. Maxwell from the kinetic theory of gases. The derivation of Fick’s law includes the following assumptions: (1) statistical laws apply; (2) the average duration of a collision is short compared to the average time between collisions, a condition pertaining to dilute solutions; (3) the particles move independently; (4) classical mechanics can be used to describe molecular collisions; (5) energy, momentum and mass are conserved in every collision; and (6) the diffusing solute particles are much larger than the solvent molecules of the liquid.

IV Diffusion Coefficient

Consider two compartments, separated by a membrane of thickness Δx, in which a substance diffuses from inside a cell (denoted as compartment i with high concentration ci) across the cell membrane into the outside medium (denoted as compartment o with low concentration co). It is assumed that the temperature and pressure are the same in both compartments. For such a system, Fick’s first law of diffusion states that the flux density ( J, mol/s-cm2) is directly proportional to the concentration gradient dc/dx (mol/cm3/cm) across the membrane.

(8.1)

(8.1)

where dN/Adt (mol/(cm2·s) is the number (dN) of moles that diffuse across a unit area (A, cm2) of the membrane during an interval of time (dt, s). The diffusion coefficient D (cm2/s).indicates how much flux will occur for a given concentration gradient.

The concentration gradient in the steady state is equal to the difference in the concentration (Δc = co−ci) of the solute on both sides of the membrane divided by the thickness of the membrane (Δx), so that:

(8.2)

(8.2)

It is assumed that the concentration gradient through the thin membrane is linear over its thickness (Δx).

The time required for diffusion to become 50, 63 or 90% complete varies directly with the square of the distance and inversely with the diffusion coefficient. Thus, diffusion is extremely fast over short distances (e.g. 10–1000 nm), but is exceedingly slow over long distances (e.g. 1 cm). For a small particle like K+ or acetylcholine (ACh+), with a D value of about 1×10−5 cm2/s, the time required for 90% equilibration to be reached over a distance of 1 μm is about 1 ms. Table 8.1 shows how the time required changes as a function of distance. The chef knows that the time required for a meat roast to cook in the middle is dependent on the thickness of the roast and the physiologist knows that there is a critical thickness (e.g. 0.5–1.0 mm) of a muscle bundle in an incubation bath that allows adequate diffusion of oxygen to the core of the strip, no matter how vigorously the bath is oxygenated.

TABLE 8.1. Calculations of Time Required for Diffusion to Become 90% Complete

| Distance d | Time t |

| 100 Å | 0.1 μs |

| 0.1 μm | 0.01 ms |

| 1 μm | 1 ms |

| 10 μm | 100 ms |

| 100 μm | 10 s |

| 1 mm | 16.7 min |

| 1 cm | 28 h |

Diffusion time varies inversely with square of diffusion distance. These approximate values are for a substance having a diffusion coefficient (D) of about 1×10−5 cm2/s in free solution. Einstein’s approximation equation is  where d is the mean displacement.

where d is the mean displacement.

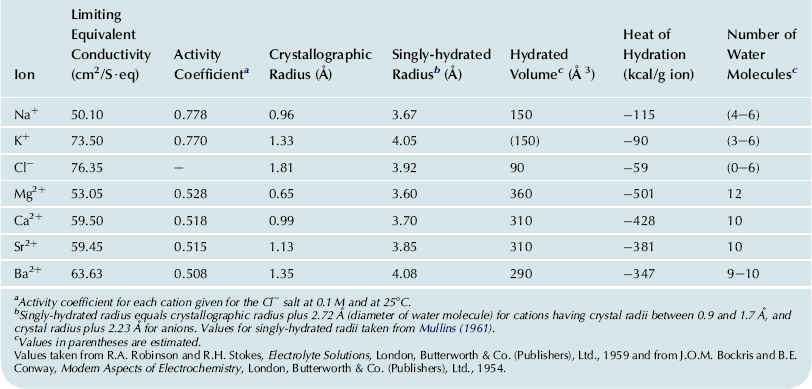

The diffusion coefficient (D) is a constant for a given substance and membrane under a given set of conditions. The diffusion coefficient of substances in free solution is dependent upon molecular size (and shape, for large molecules). For ions, the smaller the crystal (unhydrated) radius, the greater the charge density, which means that more water molecules are held in the hydration shells, thus giving a larger hydrated radius. The larger water shell causes diffusion to be slower. The hydrated and unhydrated radii of some relevant ions are given in Table 8.2. Thus, although Na+ has a lower atomic weight than K+, Na+ attracts and holds a larger hydration shell because of its greater charge density (same charge as K+, but smaller unhydrated ion size) and, therefore, Na+ diffuses in water considerably slower than does K+ (ratio of about 1: 2).

TABLE 8.2. Physicochemical Properties of Selected Ions

Values taken from R.A. Robinson and R.H. Stokes, Electrolyte Solutions, London, Butterworth & Co. (Publishers), Ltd., 1959 and from J.O.M. Bockris and B.E. Conway, Modern Aspects of Electrochemistry, London, Butterworth & Co. (Publishers), Ltd., 1954.

The diffusion coefficient is inversely related to the resistance to free diffusion and, therefore, is very much lower in water than in a gas. Graham’s law states that the diffusion coefficient of a gas is inversely proportional to the square root of the molecular weight:

(8.3)

(8.3)

Graham’s law was originally discovered by experiment and was later derived theoretically by Maxwell. The random molecular motions due to thermal energy are opposed by intermolecular attractive forces but, in dilute gases, these attractive forces are small because the molecules are relatively far apart.

The Einstein–Stokes equation applies to diffusion in liquids when spherical solute molecules are much larger than the solvent molecules, e.g. of colloidal size. The diffusion coefficient of the solute is related to the viscosity (η) of the solvent and the radius (r) of the solute particle:

(8.4)

(8.4)

where R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature and NA is Avogadro’s number.

Temperature also affects the rate of diffusion. The relative increase in the diffusion coefficient when the temperature (T) is raised by 10°C is known as Q10. For dilute solutions, the Q10 value should be the same for all molecules and is 1.03 (between 25 and 35°C). A Q10 value of 2 or 3 indicates that some process other than diffusion is probably responsible for transport.

In liquids, the solute and solvent molecules are close together. Hence, for any solute particle to move, it must first break away from its surrounding solvent molecules. Diffusion in liquids consequently occurs in a discontinuous manner. A solute molecule is able to move only when it has acquired sufficient energy by collision to break away from its solvent neighbors. Thus, the molecule diffuses in a series of jumps, each jump requiring a critical activation energy. When the attractive forces between solvent molecules are weak, diffusion is more rapid.

The Q10 for diffusion of a substance in water depends on the activation energy necessary for a jump. If a large amount of energy is required (high Q10), only a few molecules have the necessary energy to diffuse at any moment. Raising the temperature increases the number of molecules with the required energy and thereby appreciably speeds up the rate of diffusion. If only a small activation energy is required (low Q10), a greater fraction of the molecules possesses this minimal energy at any moment and so raising the temperature has less of an effect. The Q10 for diffusion of Na+ or K+ in water is only about 1.22.

The cell membrane constitutes a barrier to diffusion. In penetrating through the lipid bilayer matrix, a non-charged small solute molecule must move as follows: (1) detach itself from its surrounding solvent molecules and jump into the membrane phase; (2) move through the thickness of the membrane, perhaps by a series of small jumps over energy barriers; and (3) detach itself from the membrane and jump into the solvent phase on the opposite side of the membrane. The permeability of the membrane to the solute depends greatly on the activation energy required for the molecule to jump into and out of the membrane. If the activation energy is high, the Q10 is high and the permeability is low; if the activation energy is low, then the Q10 is low and the permeability is high.

V Diffusion Across a Membrane with Partitioning

When a solute partitions into the membrane, the concentration gradient across the membrane itself differs from that calculated from the internal and external concentrations in the bulk solutions. For example, if a solute is at 10 mM in the internal solution and at 1 mM in the external solution, the concentration gradient would be ci−co = 10−1 = 9 mM. Now suppose that the solute dissolves into the membrane phase such that the concentration just within the membrane at the internal boundary is 10-fold greater than in the internal solution and the same 10-fold partitioning occurs at the external boundary. With such partitioning, the concentrations in the membrane would be 100 mM at the internal boundary and 10 mM at the external boundary, constituting a gradient of 100−10 = 90 mM, or a 10-fold higher concentration gradient within the membrane. The partition coefficient (β) relates the concentration just within the membrane at the boundary to the external or internal concentrations. β is assumed to be equal at the internal and external boundaries of the cell membrane.

The diffusion coefficient across cell membranes for various substances is generally greater when the molecular size of the substance is small and when the lipid solubility is high; i.e. small molecules of high lipid solubility (i.e. less polar and non-polar molecules) penetrate most quickly through the membrane.

The above paragraphs present the basis for Overton’s classical rule that the rate of diffusion of many substances across cell membranes correlates with the oil/water partition coefficient. The rate of permeation of a water-soluble substance is primarily determined by how easily the substance passes from water to lipid; its oil/water partition coefficient is a measure of this ease. The more a substance dissolves in the membrane, the greater its concentration gradient within the membrane and the faster the rate of diffusion across the membrane. The data for permeation of non-electrolytes, including alcohols, into cells are an example of this mechanism.

VI Permeability Coefficient

The permeability coefficient (P, cm/s) is the product of the partition coefficient (β) and the diffusion coefficient (D) divided by the thickness (Δx), of the membrane:

(8.5)

(8.5)

Note that permeability coefficients apply only to membranes, whereas diffusion coefficients apply to both membranes and solutions. Equation 8.5 indicates that, the higher the diffusion coefficient for movement of a substance across a membrane, the higher the permeability coefficient.

The flux density (J) across the membrane is given by:

(8.6)

(8.6)

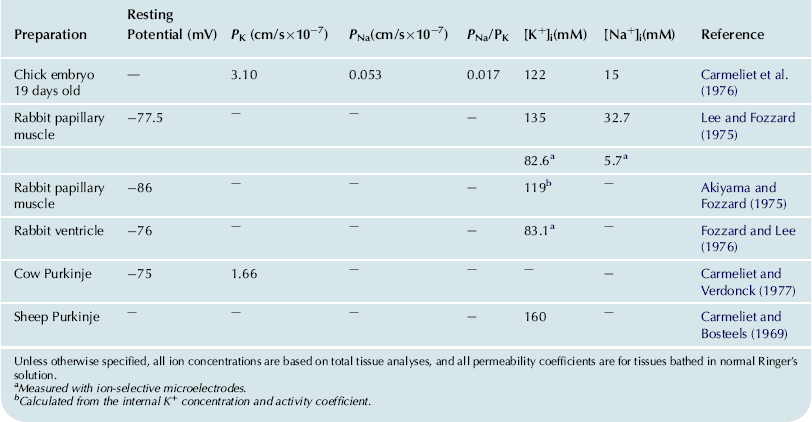

Hence the net flux density of a non-electrolyte across a membrane is equal to the permeability coefficient (P) times the difference in concentration across the membrane. The permeability coefficient for K+ (PK) across resting skeletal muscle membrane is about 1×10−6 cm/s. Some values for PK (in cm/s) are given in Table 8.3 for some cardiac tissues. The unidirectional influx (Ji) and efflux (Jo) are defined by:

(8.7a)

(8.7a)

(8.7b)

(8.7b)

The net flux is defined as the difference between the efflux and influx. Thus,

(8.8)

(8.8)

which is the same as Equation 8.6. Equations 8.7a and 8.7b show that the influx of a substance is equal to its permeability coefficient times the external concentration (co), whereas the efflux (or outflux) is equal to the permeability coefficient times the internal concentration (cI ). Algebraic manipulation shows that the permeability coefficient is equal to the ratio of flux to concentration (influx to cO and efflux to ci).

TABLE 8.3. Summary of Internal K+ and Na+ Concentrations and Permeabilities for Some Selected Heart Tissues

Unless otherwise specified, all ion concentrations are based on total tissue analyses, and all permeability coefficients are for tissues bathed in normal Ringer’s solution.

The electrical current (i, in amp) carried by Na+ is equal to the flux (J′ in mol/s) times zF (coul/mol or coul/equiv , if univalent), or

(8.9a)

(8.9a)

Converting to current density:

(8.9b)

(8.9b)

where I is the current density in amp/cm2, and J is the flux density in mol/cm2-s.

VII Electrodiffusion

Fick’s law of diffusion (Equation 8.1) applies only to uncharged molecules. If there is a net charge on the molecule, then the unidirectional fluxes are also determined by any electrical field that may exist across the membrane. The equation for the net flux is then:

(8.10)

(8.10)

where f (Em) is some function of the electrical potential difference (p.d.) across the membrane and F, R and T are the Faraday constant, gas constant and absolute temperature, respectively. Note the similarity of Equation 8.10 to Equations 8.6 and 8.8, except for the membrane potential terms. The electrical p.d. across the membrane (Em) equals ψI−ψO ,where ψI is the inside potential and ψO is the outside potential. When f(Em) is equal to EmF/RT, this term is dimensionless (EmF is the electrical energy, whereas RT is the thermal energy); RT/F = 0.026 V at 25°C. Similarly, the term  is dimensionless; therefore, the units for flux are the same as those given in Equation 8.6.

is dimensionless; therefore, the units for flux are the same as those given in Equation 8.6.

For a monovalent cation, Einstein’s law of diffusion states that:

(8.11)

(8.11)

where U is the electrophoretic mobility of the ion through the membrane and has units of a velocity per unit driving voltage gradient (cm/s per V/cm) and k is the Boltzmann constant (R/F).

Substituting Equation 8.11 into the definition of the permeability coefficient (Equation 8.5) gives:

(8.12)

(8.12)

where β is the partition coefficient (dimensionless) for the ion between the bulk solution and the edge of the membrane and Δx is the membrane thickness (cm). Equation 8.12 indicates that the permeability coefficient of an ion is directly related to the electrophoretic mobility of the ion through the membrane.

The Nernst–Planck equation states that the total flux density, Ji (mol/cm2·s), of an ion species (i) across the membrane is the sum of the flux density due to diffusion and the flux density due to the electrical potential:

(8.13)

(8.13)

The net outward flux due to diffusion, given by Fick’s law, is proportional to the concentration gradient, dci/dx:

(8.14)

(8.14)

where Di (cm2/s) is the diffusion coefficient of the ion species.

The flux of an ion is proportional to the gradient of electrochemical potential for that ion. The net flux is from the side of greater electrochemical potential to the side of lesser electrochemical potential.

for that ion. The net flux is from the side of greater electrochemical potential to the side of lesser electrochemical potential.  is a measure of the useful energy and its units are in joules/mole (just as voltage is in joules/coulomb). Electrochemical potential is composed of a chemical part (μc) and an electrical part (μe), that is,

is a measure of the useful energy and its units are in joules/mole (just as voltage is in joules/coulomb). Electrochemical potential is composed of a chemical part (μc) and an electrical part (μe), that is,

(8.15)

(8.15)

The chemical part (μc) is given by:

(8.16a)

(8.16a)

where  is the chemical potential at standard temperature and pressure and a is the activity (activity coefficient, γ, times the concentration). The electrical part (μe) is given by

is the chemical potential at standard temperature and pressure and a is the activity (activity coefficient, γ, times the concentration). The electrical part (μe) is given by

(8.16b)

(8.16b)

The difference in electrochemical potential for Na+, for example, between inside and outside  is:

is:

(8.17)

(8.17)

where Δψ = ψ2−ψ1 and is the same as Em. The activity coefficients cancel out, assuming γ2 = γ1.

VIII Special Transport Processes

Most non-polar molecules pass directly through the lipid bilayer matrix of the membrane, i.e. not through special sites (e.g. water-filled pores or channels). Small charged ions (e.g. Na+, K+, Cl−, Ca2+) pass through water-filled channels, some of which have a voltage-dependent gating mechanism. These channels can exhibit a high degree of selectivity for specific ions, with the selectivity orders not being based solely on the hydrated or unhydrated sizes of the ions. One type of ionophore, valinomycin, forms a hydrophobic cage around K+. This K+-ionophore complex is lipid soluble and passes rapidly through the lipid bilayer matrix.

Special transport proteins are normally present in the cell membrane for net uptake of nutrients, such as glucose and amino acids. Some of these are for downhill transport only, i.e. down the electrochemical gradient. One type of protein-mediated transport in cells (e.g. for glucose) is known as facilitated diffusion, a type of transport that contrasts with simple diffusion across the cell membrane. Another type of mediated transport is known as exchange diffusion, in which one molecule of substance (or ion) inside the cell is exchanged for one molecule outside the cell, in which case there is no net movement. In either type of mediated transport, the rate of downhill movement of the substance across the membrane is enhanced by the transport protein.

Mediated transport systems differ from simple diffusion in that they exhibit saturation kinetics. That is, the rate of transport increases with an increase in the substrate concentration up to a maximum, after which the rate levels off due to a finite number of available transport sites. Other characteristics of mediated transport systems include competitive inhibition, in which an inhibitor substance competes at the same site for binding to the transporter. In non-competitive inhibition, the inhibitor (non-transported) substance binds to the transporter at a site different from the transport site, but still alters or prevents binding of the usual substrate. Mediated transport exhibits greater specificity than simple diffusion; e.g. the rate of mediated transport of D-glucose is greater than for L-glucose. Because mediated transport resembles an enzymatic process involving protein conformational changes, the temperature coefficient (Q10) is also higher than for simple diffusion.

IX Ussing Flux Ratio Equation

As pointed out in Equations 8.7a and 8.7b, the unidirectional fluxes are determined also by the permeability coefficient. Ussing (1949) developed the so-called flux ratio equation, in which the ratio of influx to efflux is used (permeability cancels out). Specifically, for the ratio of Na+ fluxes (by simple electrodiffusion), the following applies:

(8.18)

(8.18)

Thus, the ratio of influx:efflux (or outflux) (passive) in a resting membrane (assuming a RP of −80 mV) is

(8.19a)

(8.19a)

Thus, the passive influx of Na+ should be 217 times greater than the passive efflux, because of the large electrochemical gradient directed inward.

The flux ratio for K+ would be

(8.19b)

(8.19b)

Thus, the passive influx should be 0.574 times the passive efflux. The K+ equilibrium potential (EK) is only slightly greater (more negative by about 14 mV) than the RP and so the passive flux ratio should be close to one.

A modified form of Equation 8.18 can be obtained by substituting the ratio of ions with  (derived from the Nernst equation), giving

(derived from the Nernst equation), giving

(8.20a)

(8.20a)

where Ei is the equilibrium potential for the cation in question, and  and

and  are the inward and outward fluxes, respectively, for ion i. The sign convention refers inside solution to outside solution. Thus, for Na+ we have

are the inward and outward fluxes, respectively, for ion i. The sign convention refers inside solution to outside solution. Thus, for Na+ we have

(8.20b)

(8.20b)

This value of 217 obtained for the flux ratio is identical to that obtained from Equation 8.19a. One advantage of Equation 8.20a is that it is obvious at a glance that when Ei = Em, the flux ratio is exactly 1.0, because e0 = 1, where e is the base (2.717) for the natural logarithm. Thus, if Cl− is passively distributed so that ECl = Em, its flux ratio should be 1.0; i.e. influx equals efflux, so there is no net flux. The larger the difference between Ei and Em, i.e. the farther the ion is from equilibrium, the greater the flux ratio.

Sometimes Equations 8.20a and 8.20b do not fit the experimental facts. The data are better fitted if the exponential term contains another factor (n), which is an empirical factor:

(8.21)

(8.21)

The best fit of the data is when n has a value of 2.5 to 4.0, depending on the membrane under investigation. One interpretation given to n is that if the length of the water-filled pore that the ion must traverse to cross the membrane is much longer than the ion diameter, as is likely, then for so-called single-file diffusion, n hits on the same side are required for the ion to complete its journey across the membrane. One could consider, for example, that there are three potential energy wells, or a chain of reactive sites, along the length of the pore, and the only way for the ion to escape the well is to receive a kinetic bump from an adjacent ion in the file. Complete permeation of an ion through the pore is more likely to happen if the ion is moving in the same direction as the majority of ions, i.e. down the electrochemical gradient. Therefore, this factor (Equation 8.21) makes the flux ratio much greater than would otherwise be predicted.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Akiyama T, Fozzard HA. Influence of potassium ions and osmolality on the resting membrane potential of rabbit ventricular papillary muscle with estimation of activity and the activity coefficient of internal potassium. Circ Res. 1975;37:621–629.

2. Bockris JO’M, Conway BE. Modern Aspects of Electrochemistry. London: Butterworths; 1954.

3. Carmeliet E, Bosteels S. Coupling between Cl flux and Na or K flux in cardiac Purkinje fibers: influence of pH Arch Int Physio. Biochim. 1969;77:57–72.

4. Carmeliet E, Verdonck F. Reduction of potassium permeability by chloride substitution in cardiac cells. J Physiol (London). 1977;265:193–206.

5. Carmeliet EE, Horres CR, Lieberman M, Vereecke JS. Developmental aspects of potassium flux and permeability of the embryonic chick heart. J Physiol (London). 1976;254:673–692.

6. Crank J. Mathematics of Diffusion. New York: Oxford University Press; 1956.

7. Danielli J. The theory of penetration of a thin membrane: Appendix. In: Danielli DF, ed. The Permeability of Natural Membranes. London: Cambridge University Press; 1943.

8. Einstein AA.D. Cowper, Transl. Investigations on the Theory of Brownian Movement. In: Furth R, ed. Methuen. London: reprinted by Dover Publications, Inc; 1926; 1956.

9. Fozzard HA, Lee CO. Influence of changes in external potassium and chloride ions on membrane potential and intracellular potassium ion activity in rabbit ventricular muscle. J Physiol (London). 1976;256:663–689.

10. Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. Currents carried by sodium and potassium ions through the membrane of the giant axon of Loligo. J Physiol (London). 1952;116:449–472.

11. Jacobs MH. Diffusion Processes. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1967.

12. Jost W. Diffusion in Solids, Liquids, Gases. New York: Academic Press; 1960.

13. Lee CO, Fozzard HA. Activities of potassium and sodium ions in rabbit heart muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1975;65:695–708.

14. Mullins LJ. The macromolecular properties of excitable membranes. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1961;94:390–404.

15. Robinson RA, Stokes RH. Electrolyte Solutions. London: Butterworths; 1959.

16. Ussing HH. Distinction by means of tracers between active transport and diffusion The transfer of iodide across isolated frog skin. Acta Physiol Scand. 1949;19:43–56.