Chapter 11

Mechanisms of Carrier-Mediated Transport

Facilitated Diffusion, Cotransport and Countertransport

Chapter Outline

I Summary

This chapter describes the functional properties of carrier-mediated transport mechanisms present in the cellular plasma membrane. The functional properties defining facilitated diffusion, cotransport and countertransport are considered with regard to the thermodynamic constraints imposed by primary and secondary active transport as well as passive transport. A stepwise kinetic model is described for each mechanism illustrating the substrate concentration dependence of the rate of transport and differences in the rate limiting steps accounting for transport. The functional properties of facilitated diffusion, cotransport and countertransport are further considered with regard to competitive and non-competitive inhibition, stoichiometric coupling and electrogenic transport. The structure–function relationship of prototypical membrane proteins mediating facilitated diffusion, cotransport and countertransport is briefly considered.

II Introduction

The selective and regulated passage of ions and non-electrolytes across the cell membrane is an essential component of cellular homeostasis. The maintenance of cell pH and volume and the accumulation of nutrients for protein synthesis and cell metabolism are physiological processes that depend on membrane transport for cells to thrive. Cell membranes are composed of phospholipids organized as a bilayer (5 nm) of two closely opposed leaflets separating the intracellular from the extracellular space. The hydrophobic properties of phospholipids make the cell membrane an impermeable barrier excluding the transfer of hydrophilic solutes that are either charged (anions and cations) or uncharged (non-electrolytes). The selective passage of hydrophilic solutes across the hydrophobic barrier, a physiological property known as membrane permeability, is mediated by the presence of membrane transport proteins that span the phospholipid bilayer. Transport proteins may be functionally subdivided into channels, pumps and carriers according to differences in the mechanism mediating ion and non-electrolyte transport. This chapter describes the mechanisms of carrier-mediated transport, which include facilitated diffusion, cotransport and countertransport.

III Electrochemical Potential

Transport mechanisms may be distinguished thermodynamically according to their ability to mediate active or passive transport. Active transport is defined as movement of a solute from a region of low electrochemical potential on one side of the cell membrane to a region of higher electrochemical potential on the opposite side.Passive transport is defined as movement of a solute from a region of high electrochemical potential on one side of the cell membrane to a region of lower electrochemical potential on the opposite side. The electrochemical potential of a solute is the partial molar free energy of the solute or the potential to do work when a difference in electrochemical potential exists across the cell membrane. The electrochemical potential of a solute on either side of the cell membrane is a function of the solute activity (or concentration in dilute solution), the solute charge and valence and the electrical potential. The difference in electrochemical potential, therefore, reflects the magnitude of the difference in transmembrane solute concentration and the difference in transmembrane voltage factored by the charge and valence of the solute. Notably, for solutes without charge, such as non-electrolytes, solute free energy is neither increased nor decreased by electrical potential and only the chemical potential of the solute is considered. Thus, the electrochemical or chemical potential difference of a solute across the cell membrane may be considered a driving force acting on solute transport. In the absence of an electrochemical potential difference or a driving force for solute transport, transport mechanisms that are passive mediate equal solute transport in the forward and reverse direction across the membrane resulting in no net transport. For anions and cations, this would occur when the chemical and electrical driving forces acting on solute transport are equal and opposite in direction across the membrane such that the net driving force is zero. For non-electrolytes, this would occur in the absence of a solute concentration gradient where transmembrane solute concentrations are equal. In both instances where no net transport occurs, the ion and non-electrolyte are at electrochemical equilibrium with the driving forces acting on the transported solutes. Where an electrochemical potential difference for a solute exists across the cell membrane, the direction of net solute transport by a passive transport mechanism will depend on the direction and magnitude of the chemical and/or electrical driving forces acting on the solute. The chemical and electrical potential difference of a charged solute or ion may occur as opposing driving forces of unequal magnitude, with the direction of net solute transport determined by the direction of the larger driving force. In no instance would a passive transport mechanism mediate net transport of a charged solute in a direction across the cell membrane that opposed both the chemical and electrical driving forces acting on the ion. The same limitation holds for net transport of non-electrolytes in a direction that opposes the chemical driving force acting on the solute.

Active transport mechanisms may be distinguished from passive transport mechanisms by the ability to generate and maintain an electrochemical or chemical potential difference for ions and non-electrolytes across the cell membrane. This requires net transfer of ions or non-electrolytes across the membrane in a direction that is opposed by the prevailing electrical gradient and/or chemical concentration gradients as driving forces acting on the transported solutes. To perform the work of moving solutes “uphill” against an electrical gradient and/or a chemical concentration gradient, active transport mechanisms require energy. The source of energy driving active transport is the hydrolysis of ATP. The direct or indirect coupling of active transport to ATP hydrolysis distinguishes primary active transport from secondary active transport. Primary active transport mechanisms, such as the ion translocating ATPases or pumps, are directly coupled to ATP hydrolysis and thermodynamically transduce the energy released upon ATP hydrolysis to the energy stored in the formation of an ion electrochemical potential difference. Secondary active transport mechanisms, such as cotransporters and countertransporters, are indirectly coupled to ATP hydrolysis and thermodynamically transduce the energy from one solute electrochemical potential difference to the energy stored in the formation of a second solute electrochemical potential difference. The indirect coupling of secondary active transport to ATP hydrolysis arises from the intermediate formation and ATP dependence of the solute electrochemical potential difference that drives secondary active transport.

IV Carrier-Mediated Transport Mechanisms

IVA Facilitated Diffusion

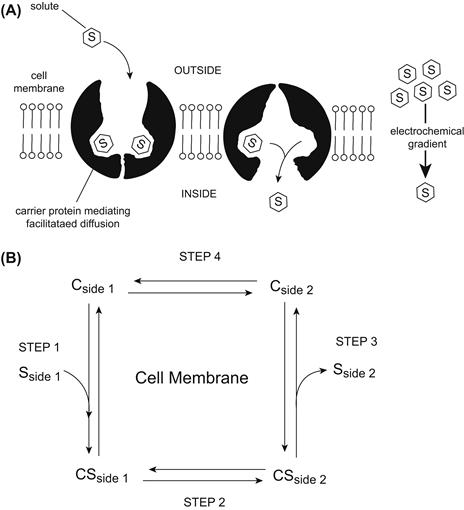

Facilitated diffusion or uniport is the simplest form of carrier-mediated transport and results in the transfer of large hydrophilic molecules (sugars, amino acids, nucleotides and organic acids and bases) across the cell membrane. Transport by facilitated diffusion is passive and reversible, with the direction of net transport into or out of the cell determined by the direction of the electrochemical potential difference of the transported solute. Net transport by facilitated diffusion may continue in either direction until the solute is at equilibrium with the electrical and/or chemical driving forces acting on the solute. At equilibrium, facilitated diffusion of a solute occurs equally in both directions resulting in no net transport. The transport mechanism mediating facilitated diffusion may be modeled as shown in Fig. 11.1. The two main features of the transport mechanism are an association and dissociation of the transported solute with the transport protein and a change in the conformation of the transport protein which makes the occupied or unoccupied site of solute interaction accessible from either side of the membrane (Fig. 11.1A). The transport mechanism may be considered in greater detail as a four-step process (Fig. 11.1B). First, solute S associates with the transport protein C facing side 1 (labeled “outside” in the figure) to form a solute–carrier complex SC. Second, the solute–carrier complex undergoes a conformational change that reorients the solute–carrier complex to face side 2 (labeled “inside” in the figure). Third, the solute dissociates with the transport protein on side 2. Fourth, the unoccupied carrier undergoes a second conformational change to reorient the solute association site to face side 1. Net solute transport from side 1 to side 2 occurs when an unoccupied solute association site is reoriented from side 2 to side 1. However, as the solute concentration on side 2 increases, net solute transport from side 1 to side 2 decreases because a greater proportion of the unoccupied carrier becomes associated with solute on side 2 and undergoes reorientation moving solute to side 1. When the solute concentrations on side 1 and side 2 are equal, no net solute transport will occur because the occupancy and reorientation of the carrier will be equal at both sides of the membrane. A principal feature of facilitated diffusion illustrated by the model is the interaction with solutes exclusively at one side of the membrane or the other but never at both sides simultaneously. This functional property of facilitated diffusion invokes the need for a conformational change in the protein, alternately orienting the solute association site from side to side across the membrane. Each step in the process is reversible and is linked to the preceding and succeeding step by rate constants defining the rate of solute association and dissociation on either side of the membrane and the rate of conformational change for transporter reorientation in either direction when associated with or without solute. In general, the rate of solute association and dissociation with the transporter occurs more rapidly than the rates of conformational change. Furthermore, the conformational change reorienting the sidedness of the transporter occurs at a faster rate for the solute-occupied transporter than for the solute-unoccupied transporter. The relative slowness of the rate constant for the conformational change reorienting the solute-unoccupied transporter (step 4) makes it the rate-limiting step in the process of facilitated diffusion.

FIGURE 11.1 Conceptual and kinetic model of facilitated diffusion.

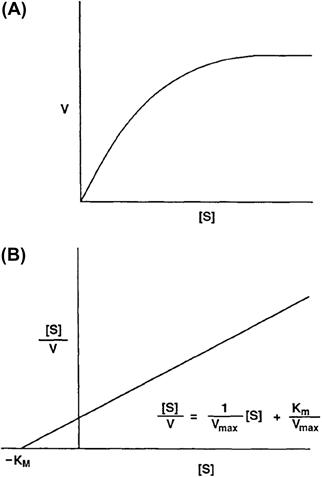

The unidirectional rate of solute transport across the cell membrane mediated by facilitated diffusion is dependent on the solute concentration at the side where transport originates. This is analogous to the substrate concentration dependence of the rate of product formation mediated by an enzyme. As shown in Fig. 11.2, at low solute concentrations the rate of solute transport increases linearly with solute concentration and, as solute concentration increases further, the rate of solute transport increases less and less as it approaches a maximum value at high solute concentrations (Fig. 11.2A). The relationship of the unidirectional solute transport rate to solute concentration shown in Fig. 11.2 is described mathematically by an equation analogous to the Michaelis–Menten equation from enzyme kinetics:

(11.1)

(11.1)

where V is determined experimentally as the initial rate of solute transport, [S] is the solute concentration, Vmax is the maximal rate of solute transport and Km is a constant described by the solute concentration where V is one-half the Vmax. The validity of using the Michaelis–Menten equation in a kinetic analysis of facilitated diffusion requires experimental conditions in which the rate of solute transport reflects solute transport only in one direction. Accordingly, initial rates of solute transport across the cell membrane are measured in the absence of a significant solute concentration on one side of the membrane. The Michaelis–Menten equation may be rearranged to obtain a linear relation as shown in Fig. 11.2B, where the kinetic parameters Km and Vmax are the x-intercept and 1/slope, respectively. The kinetic parameters of solute transport are functional properties that characterize different facilitated diffusion mechanisms as well as transport of different solutes by the same facilitated diffusion mechanism. The Km value characterizes the affinity of solute association–dissociation with the transporter such that a lower or higher Km value reflects a greater or lesser affinity, respectively. The accuracy of the Km value as a measure of solute affinity is further dependent on initial rate determinations performed at solute concentrations both above and below the Km value. The Vmax value is a measure of the number of transporters present in the membrane and the time required for a transporter to undergo one complete transport cycle or turnover. The maximum velocity of transport occurs when solute association and dissociation with the transporter are not rate-limiting steps in the transport process or when the transporter is saturated. Under these conditions, the maximal velocity of solute transport is only as fast as the rate-limiting step in the transport process, which is the conformational change of the solute dissociated transporter.

FIGURE 11.2 Relationship of solute transport rate (V) to solute concentration [S].

The facilitated diffusion of a solute may be inhibited in the presence of other solutes that interact with, but are not necessarily transported by, the same transporter. The nature of interaction of the inhibitor with the transporter may be assessed by observing the effect of the inhibitor on the kinetic parameters characterizing the transport mechanism. An effect of the inhibitor to decrease the maximal velocity of solute transport, without an effect on the Km value of the solute, characterizes non-competitive inhibition. Non-competitive inhibition is not reversed by increasing the concentration of the transported solute and therefore results from an interaction of the inhibitor with both the solute-associated and -dissociated transporter at a second site that does not interact with the transported solute. An effect of the inhibitor to increase the apparent Km value of the solute, without an effect on the maximal velocity of transport, characterizes competitive inhibition. Competitive inhibition is reversed by increasing the concentration of the transported solute and, therefore, results from an interaction of the inhibitor with only the solute-dissociated transporter at the same site that interacts with the transported solute.

The same facilitated diffusion mechanism may mediate the transport of multiple solutes that share common chemical and physical determinants, such as negatively-charged carboxyl groups or positively-charged amino groups. The nature of these chemical determinants and their spatial position in the solute molecule permits recognition and interaction with the solute association site of the transport protein. The solute specificity of a facilitated diffusion mechanism is a functional property of the transporter characterized by solute-specific differences in the kinetic parameters of solute transport. A rank order of the relative affinity of the transporter for different solutes may be compiled by determination of the Km values for multiple solutes transported by the same mechanism. The transporter is more highly specific for solutes with the lowest Km values and less specific for solutes with the highest Km values. However, solutes with higher affinity for the transporter do not necessarily have a greater maximal velocity of transport than solutes with a lower affinity. A comparison of the relative affinities and maximal velocities of solute transport determined experimentally further suggests which solutes are most likely to be transported in a physiological setting where multiple solutes are present at different concentrations.

The kinetic parameters characterizing solute transport by facilitated diffusion may differ depending on the direction of unidirectional solute transport. The Km value as a measure of solute affinity for transport may be larger or smaller for solute transport mediated in one direction across the cell membrane when compared to the Km value for solute transport in the reverse direction. However, the kinetic asymmetry of facilitated diffusion is subject to a thermodynamic limitation which requires the product of all the rate constants associated with the stepwise transport in the inward and outward direction be equal. Accordingly, a directional asymmetry in the Km value of solute transport must be matched by a corresponding asymmetry in the maximal velocity of transport such that the ratio of Vmax to Km for transport in either direction is equal. Thus, a kinetic asymmetry of solute transport results from an increase or decrease of both kinetic parameters where an increased or decreased affinity for solute is matched by a corresponding decrease or increase in maximal velocity of transport, respectively.

In contrast to non-electrolytes, the facilitated diffusion of charged solutes, such as organic anions and cations, is electrogenic and results in the net transfer of charge in the direction of net solute transport across the membrane. As a consequence of mediating net charge transfer across the membrane, the facilitated diffusion of charged solutes will increase or decrease the electrical potential difference across the membrane depending on the sign and magnitude of the solute charge and on the direction of net transport. As a further consequence of mediating net charge transfer, the rate and direction of electrogenic solute transport by facilitated diffusion is sensitive to membrane potential, which must be considered as an additional driving force acting on electrogenic solute transport. This results from the voltage sensitivity of at least one step in the transport process mediating the facilitated diffusion of charged solutes. A voltage-dependent increase or decrease in the kinetic parameters of electrogenic solute transport may indicate an effect of voltage on the affinity of the transporter for the charged solute (Km) and/or on the conformational change reorienting the solute-associated or -dissociated transporter (Vmax).

Facilitated diffusion mechanisms are present in the membranes of all cells and many different mechanisms exist in the same membrane of a single cell. The common features of these different facilitated diffusion mechanisms include: (1) their presence as integral membrane proteins spanning the lipid bilayer; (2) a broad or narrow range of substrate specificity; (3) inhibition by physiological and non-physiological solute analogs; (4) solute saturation conforming to Michaelis–Menten kinetics; and (5) evidence of an alternate side-to-side reorientation of the solute association site. Whereas solute transport via channels and facilitated diffusion are both mediated and passive, sharing the common functional properties of inhibition and saturation, other functional criteria distinguish these two forms of transport. In contrast to solute transport by facilitated diffusion, most channels mediate transport of inorganic anions or cations and have a solute specificity limited by the physical size of the ion. Channels are accessible for solute association from both sides of the membrane simultaneously and mediate transport at a rate orders of magnitude faster than facilitated diffusion, which is rate limited by the relatively slow conformational changes reorienting the sidedness of the carrier. In further contrast to solute transport mediated by facilitated diffusion, the rate-limiting step in ion transport mediated by channels is the association and dissociation of an ion with the channel, not the actual ion translocation through the channel.

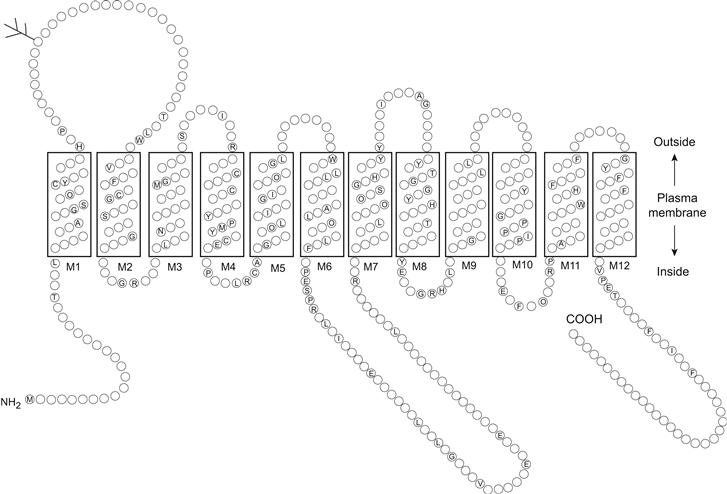

The functional properties of solute transport mediated by facilitated diffusion have been characterized in detail for many different cell- and solute-specific transport mechanisms. A major question remaining in the study of facilitated diffusion is the structure–function relationship of the transport protein. This requires the identification of individual membrane proteins as the structural correlates of transport activities of different facilitated diffusion mechanisms present in the cell membrane. A limited number of transport proteins have been identified by a difficult biochemical process involving detergent solubilization of the cell membrane, affinity purification of the protein and functional reconstitution of transport activity to prove its identity. The identification of many more transport proteins has been recently achieved using the techniques of molecular biology to clone the genes coding for these membrane proteins. The molecular cloning of a transporter gene begins with the preparation of mRNA from a tissue rich in a functionally well-characterized transporter activity. A high transporter activity suggests an abundance of transporter protein as well as transporter mRNA from which the protein is translated. The total mRNA is reverse transcribed to complementary DNA and individual cDNA molecules are inserted into plasmids or minichromosomes used to transform Escherichia coli bacterial cells. The transformed E. coli are grown to form a library of thousands of colonies or clones each reproducing a different cDNA plasmid. The library serves to renew and amplify a continuous source of cDNA plasmids which may be screened for possible hybridization with short DNA sequences thought to code for various regions of the transporter gene. To assess the function of the putative transporter gene, mRNA may be reverse transcribed from the plasmid cDNA of positively identified clones and injected into frog oocytes for translation or expression of the corresponding protein. The identity of the transporter gene is proven by the mRNA-dependent expression of a transport activity with functional properties similar to those characterizing transport activity in the tissue of origin. The transporter gene may also be identified without prescreening the library for hybridization by systematically preparing mRNA from the entire cDNA library and assessing functional expression of transport activity. The cDNA plasmid coding for the transporter gene may be sequenced to obtain the deduced amino acid sequence, or primary structure, and molecular weight of the transport protein. The deduced amino acid sequence of the transport protein may be further analyzed for the presence and concentration of hydrophobic amino acids at multiple sites along the peptide chain. Typically, 10–12 regions of relative hydrophobicity may be identified in the transporter amino acid sequence and are thought to represent the putative transmembrane domains of the transport protein. The location of the transmembrane domains further suggests the size and topological location of intracellular and extracellular peptide loops between the transmembrane domains as well as the amino and carboxy termini of the transport protein. A topological model depicting the putative secondary protein structure of a mammalian facilitated diffusion transporter for glucose is shown in Fig. 11.3. Further analysis of the amino acid sequence for the presence of asparagine in the extracellular peptide loops may suggest potential sites for N-linked glycosylation of the transport protein. Likewise, the presence of serine, threonine and tyrosine in consensus phosphorylation sites in intracellular peptide loops suggests that the phosphorylation state of the transporter may regulate its activity.

FIGURE 11.3 Consensus structure of the mammalian D-glucose carriers. (Reprinted with permission from Bell, G.I. (1991). Molecular defects in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 40, 413–422. Copyright © 1991 American Diabetes Association.)

The structure–function relationship of the protein mediating facilitated diffusion may be investigated upon identification of the primary structure or amino acid sequence of the protein. Mutant transport proteins may be engineered with single or multiple amino acid deletions, or with substitutions in the transmembrane domains, the intra- and extracellular peptide loops between transmembrane domains and in the amino and carboxy termini. The functional properties of the engineered transport proteins may be assessed by heterologous expression in frog oocytes or cell cultures and compared to the native protein. Thus, the individual amino acids or amino acid sequences important for solute recognition by, and interaction with, the transport protein may be identified as well as those involved in the conformational change reorienting the solute-associated and -dissociated transporter. The mutational analysis of transporter function is limited by null mutations which result in the expression of non-functional transport proteins or in the absence of expression.

The information obtained from identifying and cloning the gene coding for a facilitated diffusion mechanism may be used to survey the distribution of the same or related transport proteins in different tissues and in different cells within the same tissue. Oligonucleotide probes may be made from short sequences of the transporter gene and used to detect the presence of complementary transporter sequences in cDNA from tissue libraries, in mRNA prepared from multiple tissues, or by in situ hybridization of mRNA in thin tissue slices. The positively identified mRNA or cDNA may be isolated and sequenced for comparison with the deduced amino acid sequences present in different tissues. Such a comparison will indicate either complete sequence identity, suggesting the presence of the same transport protein in different tissues, or will indicate minor tissue-specific differences in sequence, suggesting that different isoforms of the same protein exist in different tissues. Thus, the facilitated diffusion of glucose in different tissues is mediated by at least five different isoforms of the same transport protein as shown in Table 11.1. The high degree of sequence conservation among different isoforms of the same transport protein is consistent with a common solute specificity and mechanism of solute translocation across the membrane. The minor tissue-specific differences in sequence distinguishing isoforms of the same protein presumably reflect a unique variation in the functional properties and/or regulation of the transporter serving the specialized physiology of the tissue.

TABLE 11.1. D–glucose Carrier Isoforms

| Designation | Function |

| GLUT1 | Basal uptake in placenta, brain, kidney, colon |

| GLUT2 | Primarily found in transport in liver cells |

| GLUT3 | Basal uptake in the brain |

| GLUT4 | Insulin-stimulated uptake in the skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle and adipose tissue |

| GLUT5 | Absorption in small intestines |

IVB Cotransport

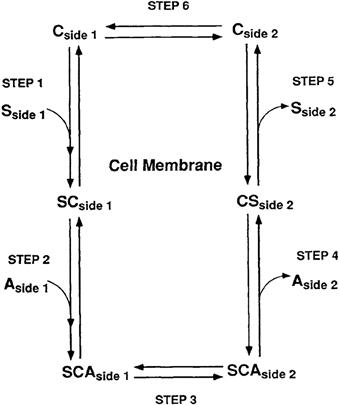

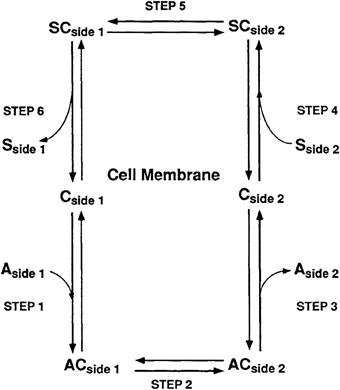

Cotransport, or symport, is a form of secondary active transport that mediates net transfer of a solute across the cell membrane from a place of low solute electrochemical potential to a place of higher solute electrochemical potential. The source of energy driving secondary active transport of a solute against its electrochemical potential difference arises from a coupling to the transport of a second solute from a place of higher electrochemical potential to a place of lower electrochemical potential. The coupling of the driving solute to the driven solute results in the cotransport of both solutes in the same direction across the cell membrane. Cotransport mechanisms are reversible and will mediate net transport either into or out of the cell until the opposing electrochemical potential differences of the driven solute and the driving solute become equal across the cell membrane. The direction of net transport mediated by a cotransport mechanism may be determined by either solute, depending on which solute has the larger driving force and by the direction of the larger driving force across the membrane. The mechanism mediating cotransport may be modeled as a six-step process as shown in Fig. 11.4: (1) an association of solutes S and (2) A with the carrier facing side 1 to form the SCA solute-carrier complex; (3) a conformational change reorienting the SCA carrier complex to face side 2; (4) dissociation of A and (5) S with the carrier facing side 2; and (6) a second conformational change reorienting the solute-free carrier to face side 1. The cotransport mechanism may be further modeled in three different variations depending on the solute interaction with the carrier. Solute interaction with the carrier may be random, with either solute associating and dissociating first with the carrier, or solute association–dissociation may be ordered, in which either one of the solutes must associate or dissociate first with the carrier before the second solute may associate or dissociate. Note, as shown in Fig. 11.4 for an ordered interaction of solute with the carrier, the second solute associating with the carrier at one side of the membrane is the first solute to dissociate with the carrier at the opposite side. Neither form of the partially associated carrier SC or AC may undergo a conformational change reorienting the sidedness of the partially associated carrier and therefore the cotransport mechanism mediates only the coupled transport of both solutes but does not mediate the uncoupled transport of either solute. Each step in the cotransport process is reversible and is linked to the preceding and succeeding step by rate constants defining the rate of solute association and dissociation on either side of the membrane and by the rate of conformational change for carrier reorientation in either direction when associated with or without both solutes. Similar to facilitated diffusion, solute association–dissociation with the carrier occurs faster than the conformational change reorienting the sidedness of the carrier and the rate-limiting step in the cotransport process is the conformational change reorienting the solute-dissociated carrier.

FIGURE 11.4 Kinetic model of cotransport.

The unidirectional rate of solute transport across the cell membrane mediated by a cotransporter is dependent on the concentration of both solutes at the side where cotransport originates. When either solute concentration is constant, the cotransport rate of the second solute will approach a maximum value with increasing solute concentration and the saturation kinetics of the cotransport process may be analyzed using the Michaelis–Menten equation to describe the kinetic parameters Km and Vmax for each solute. The random or ordered association of cotransported solutes with the transporter may be determined from the mutual dependence of kinetic parameters on cotransported solute concentrations. As shown in Fig. 11.4, where the association of solutes S and A with the cotransporter at side 1 is ordered and S associates first, solute A will have the same maximal rate of transport (Vmax) when determined at different concentrations of solute S. However, the Km value for solute A will decrease when determined at increasing concentrations of solute S, indicating the initial association of S with the cotransporter effectively increases its affinity for association with solute A. In contrast, the Vmax and Km values characterizing transport of solute S, the first solute to associate with the cotransporter, will both vary when determined at different solute A concentrations. An increase in solute A concentration will increase the maximal rate of solute S through the cotransport mechanism and will also effectively increase its affinity for solute S as reflected by a decreased Km value. The effect of solute A on the maximal rate of solute S transport arises from its ordered association, as the second solute, to form the SCA solute–carrier complex, which may then transfer both solutes across the membrane. Thus, where a mutual solute concentration dependence of the kinetic parameters characterizing the transport of both solutes is determined for a cotransport mechanism, an ordered association–dissociation of solutes with the cotransporter may be indicated and a random association–dissociation of solutes may be excluded.

The cotransport of a solute may be inhibited by the presence of other solutes that interact with, but are not necessarily transported by, the same cotransport mechanism. Similar to facilitated diffusion, the competitive or non-competitive nature of inhibitor interaction with the co-transport mechanism may be assessed by determining the effect of the inhibitor on the kinetic parameters characterizing transport of both solutes by the cotransport mechanism.

The same cotransport mechanism may mediate transport of multiple solutes that share common chemical and physical determinants. Similar to facilitated diffusion, the solute specificity of a cotransport mechanism may be characterized by determining the kinetic parameters of different solutes transported by the same cotransport mechanism. A comparison of the relative affinities and maximal velocities of solute transport determined experimentally will suggest the relative magnitudes of solute transport mediated by the cotransporter in vivo.

The cotransport mechanism modeled in Fig. 11.4 will be at a steady state and mediate equal transport of S and A in both directions across the membrane when the driving forces acting on the cotransported solutes are equal and opposite. This would occur when the transmembrane concentration difference or gradient of S in one direction is equal to the transmembrane concentration difference or gradient of A in the opposition direction. At the steady state, where no net solute transport occurs, the solute driving forces will be in thermodynamic equilibrium with each other and the transmembrane concentration ratios of S and A may be described by:

(11.2)

(11.2)

Thus, in the presence of a 10-fold concentration gradient of S, a cotransport mechanism coupling the transport of S and A across the membrane may generate up to, but not exceeding, a 10-fold concentration gradient of A. Because the cotransport mechanism effectively transduces the energy stored in the concentration gradient of S to the energy stored in the concentration gradient of A, it would be thermodynamically impossible for the cotransport mechanism to generate more than a 10-fold concentration gradient of A.

The cotransport process modeled in Fig. 11.4 describes the coupled transport of one molecule of S together with one molecule of A, or an S to A coupling ratio of 1:1. However, the stoichiometric coupling of solutes mediated by a cotransport mechanism may exceed unity, resulting in cotransport of unequal amounts of solute. This may be modeled kinetically as an extension of Fig. 11.4 to include an extra step of solute association on side 1 prior to carrier reorientation to face side 2 and an extra step of solute dissociation on side 2 prior to carrier reorientation to face side 1. The kinetic parameter (Km) characterizing the solute affinity of a cotransport mechanism must account for each additional solute association or dissociation at mutually exclusive sites in the cotransport protein. The thermodynamic equilibrium of solute driving forces defining the steady state, where no net solute transport occurs, is profoundly affected by the stoichiometric coupling of solutes by the cotransport mechanism. Where the stoichiometric coupling is other than 1:1, the solute driving forces will be in thermodynamic equilibrium at transmembrane solute concentration ratios raised to the power of their respective coupling coefficient as shown.

(11.3)

(11.3)

The coupling coefficients s and a are the number of S and A molecules that must associate with the carrier before a conformational change may occur reorienting the sidedness of the solute–carrier complex. The stoichiometric coupling of solutes by a cotransport mechanism is significant because, in the presence of a 10-fold concentration gradient of S, a cotransport mechanism coupling the transport of two molecules of S to one molecule of A may generate a 100-fold concentration gradient of A.

Similar to the facilitated diffusion of charged solutes, cotransport mechanisms may also be electrogenic and mediate net charge transfer across the membrane in the direction of net solute transport. In general, the electrogenicity of cotransport mechanisms arises from the transport of the inorganic cation sodium coupled to the transport of organic and inorganic anions and cations, such as negatively-charged amino acids, mono- and dicarboxylic acids, sulfate and phosphate or positively-charged amino acids and amines as well as non-electrolytes, such as sugars. In most instances, the coupled transport of charged or uncharged solutes with the transport of sodium results in the net transfer of positive charge in the direction of net solute transport into the cell. The positive electrogenicity of solute transport mediated by a sodium-coupled cotransport mechanism will tend to depolarize the cell membrane potential difference and results from at least one voltage-sensitive step in the process accounting for electrogenic cotransport. A voltage-dependent increase or decrease in the kinetic parameters characterizing an electrogenic cotransport mechanism may indicate an effect of voltage on the affinity of the cotransporter for either or both solutes (Km) and/or on the conformational change reorienting the solute-associated or -dissociated transporter (Vmax). However, because the rate-limiting step in the process accounting for cotransport is the conformational change reorienting the solute-dissociated transporter, a voltage-dependent increase in the rate of cotransport must result from the voltage sensitivity and acceleration of at least this step in the cotransport process. The voltage sensitivity of an electrogenic cotransport mechanism makes the voltage difference across the cell membrane a driving force acting on solute cotransport. Thus, the rate, magnitude and direction of solute transport mediated by an electrogenic sodium cotransport mechanism is determined by two driving forces including the transmembrane voltage difference as well as the transmembrane sodium and solute concentration gradients. An electrogenic cotransport mechanism will be at steady state and mediate equal solute transport in both directions across the membrane when the electrical and chemical forces driving cotransport are at equilibrium across the membrane. For an uncharged solute S, and a charged solute A, the driving forces may be related by:

(11.4)

(11.4)

where R is the universal gas constant, T is absolute temperature, z is the valence of A, F is the Faraday constant, and (ψ2−ψ1) is the transmembrane voltage difference. Thus, in the presence of a 10-fold sodium concentration gradient and a transmembrane voltage difference of 60 mV, a cotransport mechanism mediating 1:1 Na-to-solute transport may generate a 100-fold uncharged solute gradient.

The functional properties of solute transport mediated by sodium-dependent cotransport mechanisms have been characterized in detail for many different cell- and solute-specific cotransporters. Like facilitated diffusion, a major question remaining in the study of sodium-dependent cotransport mechanisms is the structure–function relationship of the cotransport protein. Several sodium-dependent cotransport proteins been identified using a molecular biological approach to clone the genes coding for these membrane proteins. The primary structure of sodium-dependent cotransport proteins suggests topological features similar to membrane proteins mediating facilitated diffusion. These include the presence of 10–12 putative transmembrane domains, the location of extracellular N-linked glycosylation sites and the location of intracellular phosphorylation sites. The structure–function relationship of the sodium–glucose cotransport protein SGLT1 has been investigated in mutagenesis studies of the cotransport protein. Intestinal glucose–galactose malabsorption is a genetic disorder resulting from multiple mutations localized in two putative transmembrane domains of SGLT1. Individual functional analysis of the different mutant SGLT1 proteins suggested the identity and location of specific amino acids that participate in the association of glucose and the inhibitor phloridzin with the cotransport protein as well as the amino acids involved in the conformational changes reorienting the solute-dissociated cotransporter. In addition to identifying the amino acids affecting the functional properties of the cotransport protein, mutagenesis studies of SGLT1 further suggest the identity and location of amino acids that participate in the membrane trafficking of cotransport proteins from its site of synthesis in the cell interior to the cell surface.

Three isoforms of the sodium–glucose cotransporter have been identified (SGLT1, SGLT2, SGLT3) and are distinguished by a high (SGLT1) or low (SGLT2, SGLT3) affinity for glucose, by differences in substrate specificity and by tissue distribution in small intestine (SGLT1) and/or renal proximal tubule (SGLT1, SGLT2). The structural basis for isoform-specific differences in function may be assessed by functional studies of chimeric proteins composed of different peptide sequence combinations from different isoforms. Thus, the chimera composed of the amino terminus including the initial seven transmembrane domains of SGLT3 and the final five transmembrane domains including the carboxy terminus of SGLT1 is observed to have the substrate specificity of the SGLT1 isoform. Accordingly, this finding indicates that the topological location of the glucose association site in the sodium–glucose cotransport protein is in a region of the peptide sequence extending from the eighth transmembrane domain to the carboxy terminus.

IVC Countertransport

Countertransport, or antiport, is a form of secondary active transport which, like cotransport, may also mediate net transfer of a solute across the cell membrane in a direction against the electrochemical potential gradient of the solute. The energy driving countertransport of a solute against its electrochemical potential difference arises from a coupling to the transport of a second solute moving across the cell membrane from a place of higher electrochemical potential to a place of lower electrochemical potential. In contrast to cotransport, the coupling of the driving solute to the driven solute in countertransport results in transport of solutes in the opposite direction across the cell membrane. Thus, countertransporters mediate the exchange of intracellular and extracellular solutes across the cell membrane. Countertransport mechanisms are reversible and will mediate net transport either into or out of the cell until the opposing electrochemical potential differences of the driven solute and the driving solute become equal across the cell membrane. The direction of net transport mediated by a countertransport mechanism may be determined by either solute, depending on which solute has the larger driving force and the direction of the larger driving force across the membrane. The mechanism mediating countertransport may be modeled as a six-step process as shown in Fig. 11.5. The principal features of the countertransport mechanism are (1, 4) a mutually exclusive association of either solute S or A with the carrier facing side 1 or side 2 to form the SC or AC carrier complex, (2, 5) a conformational change reorienting the sidedness of the solute–carrier complex and (3, 6) a dissociation of solute with carrier on the opposite side of the membrane. In contrast to the process of facilitated diffusion or cotransport, the solute-free carrier does not undergo a conformational change in countertransport and only the SC or AC carrier complex may undergo a conformational change reorienting the sided access of carrier to solute. It is the absence of a conformational change reorienting the sidedness of the solute-free carrier that explicitly distinguishes countertransport from facilitated diffusion and confers the ability to mediate net solute transport against an electrochemical potential difference. Countertransport mechanisms may mediate the exchange of the same solutes (homoexchange) or different solutes (heteroexchange) and will mediate net solute transport only when exchanging different solutes. Each step describing the process of countertransport is reversible and is linked to the preceding and succeeding step by rate constants defining the rate of solute association and dissociation on either side of the membrane and by the rate of conformational change reorienting the sidedness of the solute-associated carrier. The conformational change reorienting the sidedness of the solute-associated carrier occurs more slowly than solute association–dissociation with the carrier and is considered the rate-limiting step in the countertransport process.

FIGURE 11.5 Kinetic model of countertransport.

The unidirectional rate of solute transport across the cell membrane mediated by a countertransport mechanism depends on the concentration of both solutes at opposite sides of the membrane. When either solute concentration is constant, the countertransport rate of the second solute will approach a maximum value with increasing solute concentration and the saturation kinetics of the countertransport process may be analyzed using the Michaelis–Menten equation to obtain the kinetic parameters Km and Vmax for each of the exchanged solutes. The solute concentration dependence of the rate of solute transport by countertransport may be different for transport occurring into or out of the cell. A kinetic asymmetry of solute transport mediated by countertransport results from a difference in the apparent affinity (Km) for solute at either side of the membrane and not from a difference in the maximal rate of transport (Vmax). This limitation in kinetic asymmetry is a unique property of countertransport arising from the inability of the solute-dissociated carrier to reorient across the membrane. While kinetic asymmetry is not a property of all countertransport mechanisms, the asymmetry in solute transport mediated by a countertransporter is observed to occur for all possible combinations of solutes exchanged by the countertransport mechanism.

The countertransport of a solute may be inhibited by the presence of other solutes that interact with, but are not necessarily transported by, the same countertransport mechanism. The competitive or non-competitive nature of interaction of the inhibitor with the countertransport mechanism may be assessed by determining the effect of the inhibitor on the kinetic parameters characterizing transport of exchanged solutes by the countertransport mechanism. The same countertransport mechanism may mediate the exchange of multiple pairs of solutes that share common chemical and physical determinants. Countertransport mechanisms may be broadly categorized as either anion or cation exchange mechanisms, such as the chloride–bicarbonate countertransporter present in kidney, intestine and red blood cells or the ubiquitous pH-regulating sodium–proton countertransporter. The solute specificity of a countertransport mechanism may be characterized by determining the kinetic parameters of different solutes proven to be countertransported by the same mechanism. A comparison of the relative affinities and maximal velocities of solute transport determined experimentally will suggest the relative magnitudes of solute transport mediated by the countertransporter in vivo.

The countertransport mechanism modeled in Fig. 11.5 will be at a steady state and mediate equal transport of S and A from side 1 to side 2 and from side 2 to side 1, when the driving forces acting on solutes S and A are equal. For countertransport, this will occur when the transmembrane concentration differences of S and A are equal and in the same direction across the cell membrane. At the steady state, where no net solute transport occurs, the solute driving forces will be in thermodynamic equilibrium with each other and the transmembrane concentration ratios of S and A resulting from countertransport may be described by:

(11.5)

(11.5)

Thus, in the presence of a 10-fold concentration gradient of S, a countertransport mechanism coupling exchange of S for A may generate up to, but not exceeding, a 10-fold concentration gradient of A. Because the countertransport mechanism effectively transduces the energy stored in a 10-fold concentration gradient of S to the energy stored in a concentration gradient of A, it would be thermodynamically impossible for the countertransport mechanism to generate more than a 10-fold concentration gradient of A. The important difference distinguishing cotransport and countertransport at the steady state is the sidedness or direction of solute concentration gradients across the membrane. Cotransport is at steady state when solute concentration gradients are of equal magnitude but in opposite direction across the membrane, whereas countertransport is at steady state when solute concentration gradients are of equal magnitude and in the same direction across the membrane.

The countertransport process modeled in Fig. 11.5 describes the coupled exchange of one molecule of S for one molecule of A, or an S-to-A coupling ratio of 1:1. Whereas most countertransport mechanisms mediate the coupled exchange of single solutes, the stoichiometric coupling of solutes may exceed unity, resulting in unequal amounts of solute transported to opposite sides of the membrane. This may be modeled kinetically as an extension of Fig. 11.5 to include an extra step of solute association on side 1 prior to carrier reorientation to face side 2 and by an extra step of solute dissociation on side 2. The kinetic parameter (Km) characterizing the solute affinity of a countertransport mechanism must account for each additional solute association–dissociation at mutually exclusive sites in the countertransport protein. Similar to cotransport, the thermodynamic equilibrium of solute driving forces coupled by the countertransport mechanism and defining the steady state is profoundly affected by the stoichiometric coupling of solutes. Where the stoichiometric coupling of solutes by a countertransport mechanism is other than 1:1, the solute driving force will be in thermodynamic equilibrium at transmembrane solute concentration ratios raised to the power of their respective coupling coefficient as shown.

(11.6)

(11.6)

Thus, in the presence of a 10-fold concentration gradient of S, a countertransport mechanism coupling the exchange of two molecules of S for one molecule of A may generate a 100-fold concentration gradient of A in the same direction across the membrane.

Most countertransport mechanisms mediate the coupled exchange of single solutes with the same positive or negative charge and same valence and are therefore electroneutral and do not mediate net charge transfer across the membrane. However, when countertransport mechanisms mediate the coupled exchange of solutes of the same charge but different valence or mediate an unequal stoichiometric coupling of solutes of the same charge, a net charge transfer will occur across the cell membrane. Thus, the countertransport mechanism mediating sodium–calcium exchange across the cell membrane couples the influx of three sodium ions to the efflux of one calcium ion, resulting in a net transfer of positive charge into the cell. The positive electrogenicity of the sodium–calcium countertransport mechanism will tend to depolarize the cell membrane potential and results from the voltage sensitivity of at least one step in the process describing a complete sodium–calcium countertransport cycle. A voltage-dependent increase or decrease in the kinetic parameters characterizing an electrogenic countertransport mechanism would suggest an effect of membrane potential on the solute affinities of the countertransporter (Km) and/or on the conformational change reorienting the sidedness of the solute-associated countertransporter (Vmax). Because the conformational change reorienting the countertransporter is the rate-limiting step in the process accounting for electrogenic countertransport, a voltage-dependent increase in the rate of countertransport must result from an acceleration of at least this step. The voltage sensitivity of an electrogenic countertransport mechanism makes the cell membrane potential difference a driving force acting on solute countertransport. Thus, the rate, magnitude and direction of electrogenic countertransport of solutes across the membrane is determined by the transmembrane voltage difference in addition to the transmembrane differences in solute concentration for both solutes coupled by the countertransport mechanism. An electrogenic countertransport mechanism will be at steady state and mediate equal solute transport in both directions across the membrane when the electrical and chemical forces driving countertransport are at equilibrium. For the 1:1 exchange of charged solutes S and A with valences zS and zA, respectively, the driving forces may be related by:

(11.7)

(11.7)

The electrogenicity of a countertransport mechanism may arise from the exchange of solutes with the same charge and valence but with an unequal stoichiometric coupling. In this instance the driving forces acting on electrogenic countertransport must be factored by the stoichiometric coupling coefficients s and a for solutes S and A, respectively, and may be related by:

(11.8)

(11.8)

Thus, in the presence of a 10-fold sodium concentration gradient and a transmembrane voltage difference of 60 mV, an electrogenic countertransport mechanism mediating the 3:1 exchange of sodium and calcium ions, respectively, may generate a maximum calcium concentration gradient of 10 000-fold across the cell membrane.

The functional properties of solute transport mediated by countertransport mechanisms have been characterized in detail for many different cell- and solute-specific countertransporters. Like facilitated diffusion and cotransport, the structure–function relation of membrane proteins mediating countertransport continues to be an important question under study. The techniques of modern molecular biology have resulted in the cloning of several genes coding for countertransport proteins. Analysis of the deduced amino acid sequences of countertransport proteins suggests topological features similar to membrane proteins mediating facilitated diffusion and cotransport, including the presence of 10–12 putative transmembrane domains, the location of extracellular N-linked glycosylation sites and the location of intracellular phosphorylation sites. Low-resolution electron density maps of the red blood cell chloride–bicarbonate exchange protein have been obtained from two-dimensional crystals of the countertransport protein studied by electron microscopy. The membrane domain of the countertransport protein exists as a dimeric structure with three electron-dense regions in each monomer. Within each monomer, the configuration of electron densities suggests two closely apposed peptide structures which are spatially separated from a third structure by a peptide domain existing in two different conformations.

The structure–function relationship of the anion exchange protein AE1 has been investigated in mutagenesis studies of the countertransport protein. The functional significance of single amino acids or domains of multiple amino acids on the interaction with transport inhibitors at the extracellular side of AE1 has been studied to determine the nature and topological location of amino acids involved in substrate interaction and translocation. These mutagenesis studies involving both the deletion and substitution of amino acids indicate several positively charged lysines at the surface of AE1 influence, and are necessary for, substrate recognition by the countertransport protein. The genes coding for three anion exchange proteins (AE1, AE2, AE3) have been identified and their gene products may be functionally distinguished by differences in inhibitor sensitivity and by the intracellular pH dependence of anion exchange activity. Multiple species-specific isoforms of the AE1 gene have been identified and the predominant sites of expression are the erythropoietic tissues and the acid-secreting cells of the renal cortical collecting duct. In contrast, AE2 gene expression occurs more widely in epithelial and non-epithelial tissues and AE3 gene expression is predominant in brain and heart. The putative transmembrane amino acid sequences of AE1, AE2 and AE3 are approximately 70% identical. The aligning portion of the N-terminal cytoplasmic domains of AE1 and AE2 are only 30% identical, with little or no corresponding sequence identity among AE1, AE2 or AE3 at the N-terminus. The observed amino acid sequence identity in the putative transmembrane domains of AE1, AE2 and AE3 is consistent with the common functional properties of the three anion exchange proteins. The divergent amino acid sequences noted in the N-terminal regions suggest possible cell- and tissue-specific differences in the regulation of anion exchange activity and/or in the intracellular sorting and membrane targeting of anion exchange proteins. Mutations in the human AE1 gene in the form of nucleotide deletions, insertions and substitutions result in inheritable diseases of the red blood cell which manifest multiple clinical phenotypes ranging from mild to severe. The single amino acid substitution characterizing mutant AE1 in Band 3 Memphis has essentially no effect on red blood cell anion exchange activity. However, the nine-amino-acid deletion characterizing AE1 in Southeast Asian ovalocytosis (SAO) results in a heterozygous genetic disorder of red blood cells with only half the normal complement of functional anion exchangers. Interestingly, the red blood cell membrane of SAO patients is more resistant to plasmodial invasion, a property that may confer a selective survival advantage against malarial infection and thereby perpetuate this genetic disorder.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Alper SL. The band 3-related AE anion exchanger gene family. Cell Physiol Biochem. 1994;4:265–281.

2. Aronson PS. Identifying secondary active solute transport in epithelia. Am J Physiol. 1981;240:F1–F11.

3. Heinz E. Mechanics and Energetics of Biological Transport. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1978.

4. Heinz E. Electrical Potentials in Biological Membrane Transport. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1981.

5. Naftalin RJ. Reassessment of models of facilitated transport and cotransport. J Membrane Biol. 2010;234:75–112.

6. Neame KD, Richards TG. Elementary Kinetics of Membrane Carrier Transport. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 1972.

7. Steel A, Hediger M. The molecular physiology of sodium- and proton-coupled solute transporters. News Physiol Sci. 1998;13:123–131.

8. Stein WD. Channels, Carriers and Pumps. New York: Academic Press; 1990.