Chapter 13

Ca2+-ATPases

Chapter Outline

II. Sarcoplasmic Reticular (SR) Ca2+-ATPase

IIA. Properties of SR Ca2+-ATPase

IIB. Genetic Models to Elucidate SERCA Function In Vivo

IIC. Regulation of SR Ca2+-ATPase by Phospholamban

I Introduction

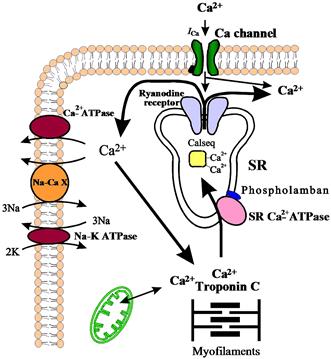

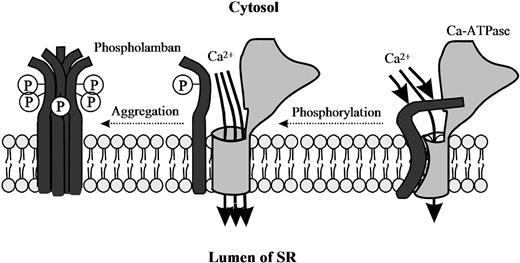

During the cardiac action potential, Ca2+ enters the cell via Ca2+ channels, which also act as dihydropyridine receptors (Fig. 13.1). This Ca2+ can either activate the myofilaments directly or produce the release of additional Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). The SR Ca2+-release channel in cardiac and skeletal muscle also acts as a ryanodine receptor and spans the gap between the transverse tubule and the SR (“foot” protein). Furthermore, it has been shown that the outer cell membrane Ca2+ channel is located close to the SR Ca2+ channel. Thus, the excitation–contraction coupling apparently involves the sarcolemmal Ca2+ channel and the SR Ca2+-release channel with the Ca2+ current through the sarcolemmal channel being responsible for the initiation of Ca2+ release from the SR (Fig. 13.1). In skeletal muscle, the sarcolemmal membrane depolarization itself apparently is responsible for the induction of SR Ca2+ release. The relative importance of release from the SR in activation of the cardiac muscle contraction varies from preparation to preparation but, in the heart of mammals, it usually accounts for 40–70% of the Ca2+ required (Bers, 2008).

FIGURE 13.1 Schematic diagram of Ca2+ fluxes in the cardiac cell. Na-CaX, Na+-Ca2+ exchanger; Calseq., calsequestrin; ICa, slow inward Ca2+ current; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum.

The rising cytosolic Ca2+ concentration induces contraction through binding to troponin C, which activates a chain of conformational changes, allowing the thin and thick filaments to interact. Subsequently, Ca2+ is dissociated from troponin C and is rapidly removed from the cytosol by various systems, resulting in relaxation. At least three processes are responsible for the removal of Ca2+ to end contraction (see Fig. 13.1): (1) the SR Ca2+ pump, which actively translocates Ca2+ at the cost of ATP into the SR system – this is thought to be the most important process in mediating relaxation; (2) the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, which transports Ca2+ out of the cell during diastole; and (3) the sarcolemmal Ca2+-ATPase, which also extrudes Ca2+ from the cell.

The SR is a tubular network which serves as a sink for Ca2+ ions during relaxation and as a Ca2+ source during contraction. In cardiac muscle, about 60–70% of the intracellular Ca2+ released during systole is taken up by the SR (Bers, 2008) and the remaining amount is extruded from the cell by the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger and the sarcolemmal Ca2+-ATPase. The SR in both skeletal and cardiac muscles contains an acidic protein, calsequestrin (see Fig.13.1), which binds 40–50 mol of Ca2+ per mol of protein (MacLennan et al., 2002). The binding and release of Ca2+ by calsequestrin is believed to be an integral step of excitation–contraction coupling, but the details of this process are still not fully understood. Mitochondria can also accumulate large amounts of Ca2+ under pathological conditions (ischemia, Ca2+ overload, etc.) (Bers, 2008).

II Sarcoplasmic Reticular (SR) Ca2+-ATPase

IIA Properties of SR Ca2+-ATPase

The major protein in the SR membrane is the Ca2+-ATPase (Mr 100 000), representing about 40% of the total protein in cardiac SR. The cardiac SR Ca2+-ATPase can create intraluminal Ca2+ concentrations of 5–10 mM. The SR or endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+-ATPase family (SERCA) is the product of at least three alternatively spliced genes, producing a minimum of 11 different proteins (Dally et al., 2010) (Table 13.1). SERCA1 is expressed in fast skeletal muscle and alternative splicing of the 3′ end of the primary transcript gives rise to two mRNA forms (SERCA1a and SERCA1b), which are expressed at different stages of development (Brini and Carafoli, 2009). Alternatively, spliced forms of SERCA2 have been detected in cardiac muscle and slow skeletal muscle (SERCA2a) and in adult smooth muscle and non-muscle tissues (SERCA2b). A third isoform of SERCA2 (SERCA2c) is found in cardiac muscle as well as non-muscle tissue including epithelial, mesenchymal and hematopoietic cells (Gianni et al., 2005). SERCA3 is expressed in a selective manner, with the highest mRNA levels in intestine, spleen, lung, uterus and brain. The human SERCA2 gene is localized on chromosome 12 and maps to position 12q23-q24.1. SERCA2 is about 85% identical to SERCAl, whereas SERCA3 is about 75% identical to either SERCA1 or SERCA2. The SERCA isoforms have different rates of transport, affinities for Ca2+ and subcellular compartmentalization.

TABLE 13.1. Structure and Distribution of the Sarcoplasmic Reticular Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) Isoforms

| Gene | Splice | Tissue |

| SERCA1a | ab | Adult fast skeletal muscle |

| SERCA1 | b | Neonatal fast skeletal muscle |

| SERCA2 | a | Cardiac/slow skeletal muscle |

| SERCA2 | b | Smooth muscle/non-muscle |

| SERCA2 | c | Cardiac/non-muscle |

| SERCA3 | a–f | Various tissues |

a The SERCA numbers identify different gene products.

b The letters a and b indicate spliced isoforms.

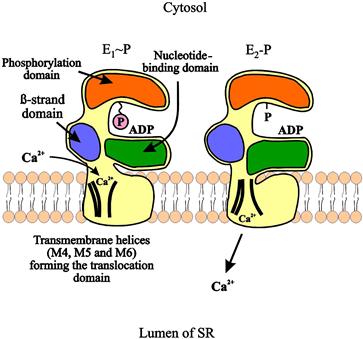

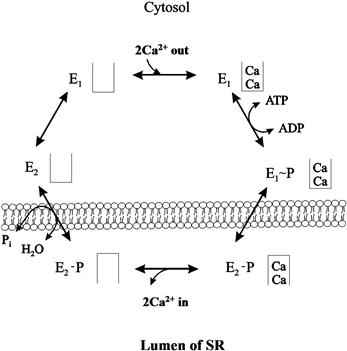

The proposed general model of the enzyme has three cytoplasmic domains joined to a set of 10 transmembrane helices by a narrow extramembrane pentahelical stalk (MacLennan et al., 2002). The cytoplasmic region includes a nucleotide-binding site, or a domain to which the MgATP substrate binds, and a phosphorylation domain (Fig. 13.2). The third cytoplasmic domain is the actuator domain, which may be involved in conformational changes. In skeletal muscle, 2 mol of Ca2+ is transported per mole of ATP hydrolyzed. In cardiac muscle, a similar stoichiometry is expected, but this ratio has been generally found to be lower (0.4–1.0 mol Ca2+/mol ATP). Ca2+ has been shown to bind to a region involving several of the membrane-spanning α-helices (M4, M5, M6 and M8) on the cytoplasmic side (MacLennan et al., 2002). During the Ca2+ transport cycle, the enzyme undergoes a transition from a high-affinity state to a low-affinity state for Ca2+ and the ions are translocated from the binding sites into the lumen of the SR (Fig. 13.2). This reaction pathway is characterized by the covalent phosphorylated Ca2+-ATPase form (E1~P), when the energy of ATP is transferred to an acylphosphoprotein intermediate (Fig. 13.3). E1~P rapidly becomes E2–P when the energy contained originally in the acylphosphoprotein is transduced into the translocation of bound Ca2+ into the SR (“marionette” model, see Fig. 13.2) in exchange for two to three protons from the lumen of the SR to the cytosol. Subsequently, the acid-labile intermediate (E2–P) decomposes to enzyme (E2) and inorganic phosphate (Møller et al., 2005).

FIGURE 13.2 Model illustrating Ca2+ translocation by SERCA-type Ca2+ pumps. In E1~P conformation, Ca2+ binds to the high-affinity binding sites in the cytosol. The energy of the hydrolyzed ATP triggers a series of conformational changes and transforms the E1~P intermediate to the E2–P intermediate. These conformational changes are directly coupled to alterations in the orientation of the transmembrane regions, leading to Ca2+ release into the lumen of the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

FIGURE 13.3 Reaction scheme of sarcoplasmic reticular Ca2+-ATPase.

The Ca2+-free form of the enzyme exists in two different conformational states: one with low affinity for Ca2+ (E2) and one with high affinity for Ca2+ (E1) (see Fig. 13.3). The conversion of E2 to E1 is proposed to be the rate-limiting step in the cycle. Thapsigargin (a plant sesquiterpene lactone) has been shown to interact specifically with the M3 transmembrane segment of the E2 form of all members of the SR Ca2+-ATPase family and to inhibit enzyme activity even at subnanomolar concentrations (Brini and Carafoli, 2009). It has been shown that the cardiac SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA2) can be phosphorylated by the Ca2+/CAM-dependent protein kinase at Ser 38 (Toyofuku et al., 1994). However, the physiological role of this phosphorylation is still not fully understood.

IIB Genetic Models to Elucidate SERCA Function In Vivo

Human mutations in both SERCA1 and SERCA2 genes have been identified and linked to disease. Brody myopathy, an autosomal recessive disorder, can be caused by mutations in SERCA1 and results in defective muscle relaxation contributing to cramping and stiffness with exercise (Odermatt et al., 1996). Another genetic disease presenting as a skin disorder, Darier disease, is caused by a mutation in the SERCA2 gene (Sakuntabhai et al., 1999) and results in decreased SERCA2 protein expression.

SERCA isoform gene-targeted mouse models have also been designed to elucidate further the function of the Ca2+-ATPase in physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Ablation of the SERCA1 gene was not embryonically lethal in mice. However, these mice had respiratory malfunction, likely due to reduced Ca2+ uptake by the diaphragm, resulting in death soon after birth (Pan et al., 2003). Consistent with Brody myopathy, the SERCA1 knockout mice had impaired limb movement and cramping (Pan et al., 2003). In the case of SERCA2, mice lacking one copy of the SERCA2 gene had decreased myocyte contractility and SR Ca2+ load, compared to wild-type (WT) mice (Ji et al., 2000). Moreover, mean arterial blood pressure and cardiac function was depressed in vivo in SERCA2 heterozygous mice (Periasamy et al., 1999). Interestingly, these mice did not develop heart failure spontaneously, but exhibited reduced function and increased susceptibility to heart failure development upon aortic constriction (Schultz et al., 2003). Similar to Darier disease in humans, which is associated with SERCA2 mutations, mice lacking one copy of SERCA2 have defects in keratinocytes and develop squamous cell tumors (Liu et al., 2001). To determine further the function of the major cardiac isoform of SERCA2, SERCA2a, another model was generated with SERCA2a ablation. There were cardiac malformations observed in this mouse and SERCA2b was upregulated. SERCA2a null mice developed cardiac hypertrophy and had decreased cardiac contractility and impaired relaxation (Ver Heyen et al., 2001). Gene ablation of SERCA3 in mice did not result in any gross phenotypes or lethality. Ca2+ handling in endothelial cells and endothelium-dependent smooth muscle relaxation was impaired in SERCA3 null mice (Liu et al., 1997). Conversely, overexpression of SERCA1a or SERCA2a in the heart in transgenic mice increased Ca2+ transport by the pump. This translated to improved cardiac function with increases in cardiac contraction and relaxation (Baker et al., 1998; Loukianov et al., 1998). Together these studies indicate SERCA is important in maintaining proper Ca2+ cycling in the cell. Loss of SERCA impairs calcium uptake which can result in altered tissue function and disease phenotypes while overexpression of SERCA1a or 2a improves cardiac function.

IIC Regulation of SR Ca2+-ATPase by Phospholamban

IIC1 Structure of Phospholamban

In cardiac muscle, slow-twitch skeletal muscle and smooth muscle, SERCA2a can be regulated by a low-molecular-weight protein, phospholamban, which can be phosphorylated by various protein kinases. In the dephosphorylated form, a substantial fraction of phospholamban monomers (20%) exists and this has been proposed to be the active species of phospholamban that binds SERCA2 and inhibits it. Upon phosphorylation, phospholamban appears to form mainly pentamers, which is due to changes in the isoelectric point (from 10 to 6.7) of the protein (Simmerman and Jones, 1998).

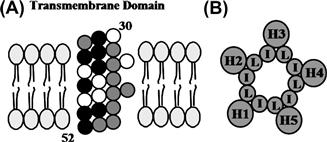

The complete amino acid sequence of phospholamban has been determined for various tissues and species. There is currently no evidence for the existence of any isoforms for this protein and the phospholamban gene has been mapped to human chromosome 6 (Fujii et al., 1991). The calculated molecular weight of phospholamban is 6080 Da and the protein has been proposed to contain two major domains (Fig. 13.4): a hydrophilic domain (domain I) with three unique phosphorylatable sites (Ser 10, Ser 16 and Thr 17), and a hydrophobic C-terminal domain (domain II) anchored into the SR membrane. The hydrophilic domain (amino acids 1–30) has been further divided into two subdomains: domain Ia (amino acids 1–20) and Ib (amino acids 21–30). Domain Ia has a net positive charge in the dephosphorylated form and consists of an α-helix followed by a Pro residue at position 21 (stalk region). Domain Ib has been suggested to be relatively unstructured (MacLennan et al., 1998, 2002). The hydrophobic domain (amino acids 31–52) forms an α-helix in the SR membrane (Fig. 13.4).

FIGURE 13.4 Molecular model of the structure of phospholamban. The cytoplasmic α-helix (domain Ia, residues 8–20) is interrupted by Pro 21 (heavy circle). Residues 22–32 (domain Ib) are relatively unstructured and may interconvert between transient conformations; residues 33–52 constitute the transmembrane domain II (α-helix). Ser 16 and Thr 17 (black circles) are the adjacent phosphorylation sites. The shaded circles indicate the leucines (Leu 37, Leu 44 and Leu 51), which are important for the phospholamban subunit interactions (pentamer formation).

Phospholamban migrates as a 24- to 28-kDa pentamer on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gels and dissociates into dimers and monomers upon boiling in SDS before electrophoresis. Spontaneous aggregation of phospholamban into pentamers was also observed upon expression of this protein in bacteria or in mammalian cells. Site-specific mutagenesis experiments identified Cys (Cys 36, Cys 41 and Cys 46), Leu (Leu 37, Leu 44 and Leu 51), and Ile (Ile 40 and Ile 47) residues in the hydrophobic transmembrane domain as essential amino acids for phospholamban pentamer formation (reviewed in MacLennan et al., 1998). The leucine and isoleucine amino acids are suggested to form five zippers in the membrane that stabilize the pentameric form of the protein with a central pore (Fig. 13.5), defined by the surface of the hydrophobic amino acids (Simmerman and Jones, 1998).

FIGURE 13.5 Model of the transmembrane domain of phospholamban monomer (A) and pentamer (B). (A) Residues 31–52 of monomeric phospholamban are configured as a 3.5 residues/360° turn helix. Darkly shaded circles represent mutations that enhance the inhibitory function of phospholamban by enhanced monomer formation (destabilization of pentamer structure). Lightly shaded circles represent mutations that reduce inhibitory function. (B) The phospholamban pentamer model shows the interaction between the monomer transmembrane domains (H1–H5) at Leu (L) and Ile (I) residues constituting zippers.

Monoclonal antibodies raised against phospholamban stimulate SR Ca2+ uptake in vitro (Morris et al., 1991). Furthermore, removal of phospholamban from the SR or uncoupling phospholamban from the Ca2+-ATPase (using detergents, high-ionic-strength solutions or polyanions such as heparin sulfate) markedly increases the affinity of the SR Ca2+ pump for Ca2+. These findings suggest that the dephosphorylated form of phospholamban is an inhibitor of the SR Ca2+-ATPase. This “depression hypothesis” has been confirmed by studies using purified Ca2+-ATPase and purified or recombinant phospholamban in reconstituted systems. Inclusion of phospholamban resulted in inhibition of the SR Ca2+-ATPase activity in reconstituted vesicles or cells (Kim et al., 1990; Reddy et al., 1996). Cyclic AMP phosphorylation of phospholamban reversed its inhibitory effect on the Ca2+ pump. The inhibitory role of phospholamban on SR and cardiac function has been directly confirmed using transgenic animal models. Overexpression of the protein (phospholamban-overexpressing mice) was associated with inhibition of SR Ca2+ transport, Ca2+ transient and depression of basal left ventricular function (Kadambi et al., 1996). On the other hand, partial (phospholamban-heterozygous mice) or complete ablation of the protein (phospholamban-deficient mice) in mouse models was associated with increases in SR Ca2+ transport and cardiac function (Luo et al., 1994, 1996; Hoit et al., 1995). Actually, a close linear correlation between the levels of phospholamban and cardiac contractile parameters was observed (Lorenz and Kranias, 1997), indicating that phospholamban is a prominent regulator of myocardial contractility. These findings suggest that changes in the level of this protein will result in parallel changes in SR function and cardiac contractility.

The region of phospholamban interacting with the Ca2+-ATPase may involve amino acids 2–18 (reviewed in MacLennan et al., 1998). Based on these reports, the simplest model for the interaction between the phospholamban cytoplasmic domain and the SR Ca2+-ATPase is one in which the highly positively-charged region of phospholamban (residues 7–16) interacts directly with a negatively-charged region on the surface of the Ca2+-ATPase (Lys-Asp-Asp-Lys-Pro-Val 402) to modulate the inhibitory interactions between the two proteins (Fig. 13.6) (reviewed in MacLennan et al., 1998). This association is disrupted by phosphorylation of Ser 10, Ser 16 or Thr 17 (phosphorylated by protein kinase C, cAMP-dependent and Ca2+-calmodulin dependent protein kinase, respectively) in phospholamban, because the positive charges of the phospholamban cytosolic domain are partially neutralized by the phosphate moiety in this vicinity. Phosphorylation of phospholamban by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase at Ser 16 is associated with local unwinding of the α-helix at position 12–16 resulting in conformational changes in the recognition unit of the protein (Mortishire-Smith et al., 1995).

FIGURE 13.6 Model for regulation of SR Ca2+-ATPase by phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated phospholamban. Phosphorylation of phospholamban disrupts the interaction between the two proteins so that the inhibition of the Ca2+-ATPase is relieved. Note that both the cytosolic domain and the membrane-spanning region of phospholamban are involved in the phosphorylation-mediated conformational change to relieve the inhibition. Phosphorylation of phospholamban monomers promotes association into inactive phosphorylated pentamers.

Interestingly, phospholamban peptides, corresponding to the hydrophobic membrane-spanning domain, also affect Ca2+-ATPase activity by lowering its affinity for Ca2+ (reviewed in MacLennan et al., 1998). The importance of the membrane-spanning region of phospholamban in inhibiting SR Ca2+-ATPase activity was demonstrated through mutagenesis studies (reviewed in MacLennan et al., 1998). It was shown that substitution of the pentamer-stabilizing residues (Leu 37, Leu 44, Leu 51, Ile 40 and Ile 47) in the membrane-spanning region (domain II) by Ala resulted in monomeric mutants, which were more effective inhibitors of the SR Ca2+-ATPase activity than wild-type phospholamban. These phospholamban monomeric mutants were called “supershifters” because they decreased the apparent affinity of SR Ca2+-ATPase more effectively than wild-type phospholamban. Thus, it was proposed that monomeric phospholamban is the active form, which is involved in the interaction with SR Ca2+-ATPase. Furthermore, scanning alanine-mutagenesis studies have identified the amino acid residues in the transmembrane domain of phospholamban (Leu 31, Asn 34, Phe 35, Ile 38, Leu 42, Ile 48, Val 49 and Leu 52), which are associated with loss of function (reviewed in MacLennan et al., 1998). These amino acids are located on the exterior face of each helix in the pentameric assembly of phospholamban (opposite from the pentamer-stabilizing face) (see Fig. 13.5). The importance of these transmembrane domain residues of phospholamban to SR Ca2+-ATPase function has been demonstrated in vivo using several transgenic models. N27A phospholamban can act as a superinhibitor, where hearts have depressed Ca2+-ATPase activity and cardiac function, that cannot be recovered completely by β-adrenergic stimulation and progressed to heart failure (Zhai et al., 2000; Schmidt et al., 2002). Mice expressing the V49G variant in the phospholamban transmembrane domain exhibited diminished cardiac function and hypertrophy which progressed to dilated cardiomyopathy (Haghighi et al., 2001). Moreover, L37A and I40A phospholamban transgenic mice showed similar decreased function and pathology (Zvaritch et al., 2000).

A schematic representation of interaction of phospholamban with SR Ca2+-ATPase is shown in Fig. 13.6. It has been proposed that the phospholamban monomer is the active species for interaction with the SR Ca2+-ATPase and the pentamers are regarded as functionally inactive forms of phospholamban (MacLennan et al., 1998). Phosphorylation of phospholamban monomers promotes association into inactive pentamers. Thus, two important steps for SR Ca2+-ATPase inhibition have been suggested: (1) dissociation of monomeric phospholamban from dephosphorylated pentamers (Kd1); and (2) binding of phospholamban monomers to the SR Ca2+-ATPase (Kd2). These dissociation constants (Kd1 and Kd2) will control both the concentration of phospholamban monomers and the concentration of units in which monomers are associated with the SR Ca2+-ATPase (MacLennan et al., 1998). There are at least two interaction sites between phospholamban and the SR Ca2+-ATPase (see Fig. 13.6): one in the cytoplasmic domains of the two proteins and another one within the transmembrane sequences. The interaction between the hydrophobic membrane-spanning regions is associated with inhibition of the apparent affinity of SR Ca2+-ATPase for Ca2+ (KCa). The interaction between the cytosolic phospholamban domain Ia and the SR Ca2+-ATPase modulates the inhibitory interaction in the transmembrane region (domain II) through long-range coupling. Disruption of the cytosolic interactions (domain Ia) by phosphorylation of phospholamban or binding of a phospholamban antibody results in disruption of the inhibitory intramembrane interactions. However, resolution of the exact molecular mechanism by which phospholamban inhibits the SR Ca2+-ATPase Ca2+ affinity and the concomitant regulation of SR Ca2+ transport will have to await the development of a new methodology that allows detection of protein–protein interactions in a membrane environment.

IIC2 In Vitro Studies on Regulation of SR Ca2+-ATPase

In the early 1970s, it was suggested that the effects of various catecholamines on cardiac function may be partly attributed to phosphorylation of the SR by cAMP-dependent protein kinase(s). It soon became clear that the substrate for the protein kinase (PK) was not the SR Ca2+-ATPase but phospholamban. Various other high- and low-molecular-weight SR proteins were also identified as minor substrates for cAMP-dependent PK, but only the changes in the phosphorylation of phospholamban were associated with functional alterations of the cardiac SR.

cAMP-dependent and Ca2+-CaM-dependent PKs have been shown to phosphorylate phospholamban independently of each other (reviewed in Mattiazzi et al., 2005). Phosphorylation by cAMP-dependent PK occurred on Ser 16, whereas Ca2+-CaM-dependent PK catalyzed exclusively the phosphorylation of Thr 17 (reviewed in Mattiazzi et al., 2005). Phosphorylation by either kinase was shown to result in stimulation of the SR Ca2+-ATPase activity and the initial rates of SR Ca2+ transport. Stimulation was associated with an increase in the apparent affinity of the SR Ca2+-ATPase for Ca2+ (KCa).

In vitro, phospholamban is phosphorylated by two additional PKs: PK-C and a cGMP-dependent PK. Protein kinase C (Ca2+/phospholipids-dependent PK) phosphorylated the protein at a site distinct (Ser 10) from those phosphorylated by either cAMP-dependent PK or Ca2+-CaM-dependent PK (reviewed in Mattiazzi et al., 2005). Phosphorylation stimulated the SR Ca2+-ATPase activity and it was postulated that this activity played a role in the action of agents known to stimulate phosphoinositide (PI) hydrolysis, since one product of PI hydrolysis, diacylglycerol, is an activator of PK-C. Cyclic GMP-dependent PK was shown to phosphorylate phospholamban on the same residue (Ser 16) as that phosphorylated by cAMP-dependent PK (reviewed in Mattiazzi et al., 2005). This phosphorylation stimulated cardiac SR Ca2+ transport, similar to the effects of cAMP-dependent PK. Furthermore, the stimulatory effects on Ca2+ transport, mediated by cGMP-dependent phosphorylation of phospholamban, were also observed in smooth muscle and this may be of particular interest because some vasodilators act by increasing cGMP levels in vascular smooth muscle.

IIC3 In Vivo Studies on Regulation of SR Ca2+-ATPase

The phosphorylation of SR proteins and their regulatory effects on the SR Ca2+-ATPase activity have been studied in perfused hearts from various animal species whose ATP pool was labeled with [32P]orthophosphate. Microsomal fractions enriched in SR were prepared from hearts freeze-clamped during stimulation with different agonists (catecholamines, forskolin, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, phorbol esters) and analyzed by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography for 32P incorporation. β-Adrenergic agonist (isoproterenol) stimulation of the perfused hearts produced an increase in 32P incorporation into phospholamban (Kranias and Solaro, 1982; Lindemann et al., 1983). The stimulation of 32P incorporation into phospholamban was associated with an increased rate of Ca2+ uptake into SR membrane vesicles and an increased SR Ca2+-ATPase activity (Lindemann et al., 1983; Kranias et al., 1985).

These biochemical changes were associated with increases in left ventricular functional parameters (contractility and relaxation). The in vivo phosphorylation of phospholamban was specific only for inotropic agents that increased the cAMP content of the myocardium (β-adrenergic agonists, forskolin and phosphodiesterase inhibitors). On the other hand, positive inotropic interventions, which increased the intracellular Ca2+ level by cAMP-independent mechanisms (α-adrenergic agonists, ouabain and elevated [Ca2+]), failed to stimulate phospholamban phosphorylation and relaxation. Calmodulin inhibitors (fluphenazine) attenuated the isoproterenol-induced phosphorylation of phospholamban (Lindemann and Watanabe, 1985a) and it was shown that at steady-state isoproterenol exposure, phospholamban contains equimolar amounts of phosphoserine (pSer 16) and phosphothreonine (pThr 17). Phosphorylation of Ser 16, however, correlated most closely with changes in cardiac function in beating hearts (Talosi et al., 1993). Based on these results and findings in transgenic animals (Luo et al., 1998), it is proposed that: (1) prevention of Ser 16 phosphorylation (Ser 16 → Ala mutation) results in attenuation of the β-adrenergic response in mammalian hearts; and (2) that phosphorylation of Ser 16 is a prerequisite for Thr 17 phosphorylation. Indeed, in mice containing an alanine substitution for Ser 16, there were diminished responses to the β-adrenergic stimulation. Also, in these animals there was no phosphorylation at Thr 17 (Luo et al., 1998). Conversely, substituting alanine for Thr 17 did not interfere with phosphorylation of Ser 16, and hearts were responsive to β-adrenergic stimulation (Chu et al., 2000). Moreover, overexpression of a non-phosphorylatable form of phospholamban (both Ser 16 and Thr 17 sites mutated to Ala) resulted in maximum inhibition of the SR Ca2+-ATPase calcium affinity (Brittsan et al., 2000). It should be noted that, in some conditions, Thr 17 has been shown to be phosphorylated independently of Ser 16, such as increased frequency stimulation of the heart, elevated intracellular Ca2+, ischemia-reperfusion injury and acidosis (Zhao et al., 2004; Mattiazzi et al., 2005).

The muscarinic agonist acetylcholine attenuated the increases in cAMP levels, phosphorylation of phospholamban and the SR Ca2+-ATPase activity produced either by β-adrenergic stimulation or by phosphodiesterase inhibition (using isobutylmethylxanthine) (Lindemann and Watanabe, 1985b). Protein kinase C and cGMP-dependent PK, which have been shown to phosphorylate phospholamban in vitro, failed to demonstrate similar effects in beating guinea pig hearts in response to stimuli that activate PK-C or elevate the cGMP levels (Huggins et al., 1989; Edes and Kranias, 1990). Thus, the physiological relevance of PK-C and PK-G in beating hearts is not clear at present.

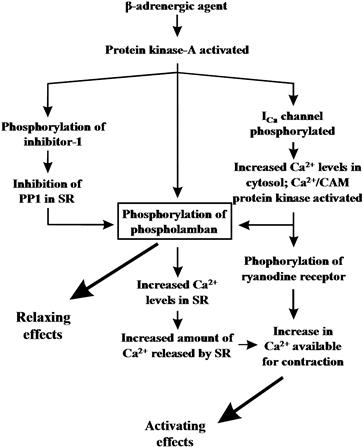

The functional alterations in the SR Ca2+-ATPase activity may explain, at least partly, the activating and relaxing effects of β-adrenergic agents in cardiac muscle (Figs. 13.7 and 13.8). The cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of phospholamban under either in vitro or in vivo conditions increases the rate of SR Ca2+ transport and SR Ca2+-ATPase activity. Such an increase in Ca2+ transport is expected to contribute primarily to the relaxing effects of catecholamines (Fig. 13.7). An additional mechanism which contributes to the increased phosphorylation of phospholamban upon β-adrenergic stimulation is the phosphorylation of the phosphatase inhibitor protein by the stimulated cAMP-dependent kinase. This phosphorylation results in inactivation of protein phosphatase 1 and, thus, inhibition of dephosphorylation of phospholamban during the action of catecholamines (Fig. 13.7). The increased phosphorylation of phospholamban and the increased Ca2+ levels accumulated by the SR would lead to the availability of higher levels of Ca2+ to be subsequently released for binding to the contractile proteins (Fig. 13.7). The critical and prominent role of phospholamban in the mediation of β-adrenergic functional responses was also confirmed in transgenic animal studies. Cardiac myocytes or work-performing heart preparations from phospholamban-deficient mice exhibited largely attenuated responses to β-adrenergic agonist stimulation (Luo et al., 1996; Wolska et al., 1996), indicating that phospholamban is a key phosphoprotein in the heart’s responses to β-adrenergic agonists.

FIGURE 13.7 Schematic diagram of possible relaxing and activating effects of β-adrenergic agents in the heart. PP1, protein phosphatase 1.

FIGURE 13.8 Effects of β-adrenergic agents on protein phosphorylation in cardiac cells. Increased intracellular cAMP levels activate the cAMP-dependent protein kinase(s), which phosphorylates various proteins (phospholamban, inhibitor-1, Ca2+-channel and myofibrillar proteins) and increases the rates of SR Ca2+ uptake and release.

Phosphorylation of other myocardial phosphoproteins has also been suggested to be involved in the mediation of positive inotropic and lusitropic effects of β-adrenergic agonists. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase-mediated phosphorylation of the α1 subunit of the Ca2+ channel (see Fig. 13.8) is associated with an increase in the voltage-dependent Ca2+ current (ICa), which enhances the Ca2+ levels available in the cytosol during β-adrenergic agonist stimulation. Phosphorylation of troponin I has been shown to decrease the sensitivity of myofilaments for Ca2+ both in intact myocardium and skinned fibers (Kranias et al., 1985). The desensitization of myofibrils is accompanied by an increased off-rate of Ca2+ from troponin C, which could contribute to faster relaxation (see Fig. 13.8). In addition, phosphorylation of the SR Ca2+-release channel (ryanodine receptor) by Ca2+-CaM-dependent protein kinase may stimulate Ca2+ release from the SR vesicles and contribute to the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ levels during systole. Thus, the enhanced Ca2+ influx across the sarcolemma, together with the increased Ca2+ levels to be released from the SR, may result in an elevation of the Ca2+ available for the contractile machinery, leading to an increase in the amplitude of contraction (see Fig. 13.8).

In recent years, several human mutations in the phospholamban gene have been identified and additional insights into phospholamban regulation of SERCA2 have been obtained. The first mutation discovered encoded Arg 9 Cys, which is included in the PKA phosphorylation consensus sequence of phospholamban. This mutation reduced the phosphorylation of phospholamban in vitro and in vivo using a gene-targeted mouse model (Schmitt et al., 2003). Two human mutations, Leu 39 stop and Arg 14 del, in phospholamban interfered with targeting of the protein to the endoplasmic reticulum. The Leu 39 stop mutation produces a truncated phospholamban protein that, when introduced in HEK 293 cells, resulted in an unstable protein that was misrouted to other membranes. Cardiac explants from human carriers of Leu 39 stop had no detectable phospholamban in the endoplasmic reticulum (Haghighi et al., 2003). Deletion of Arg 14 also interfered with targeting of phospholamban to the endoplasmic reticulum (Sharma et al., 2010). Mice expressing the Arg 14 del mutation had ventricular dilation and fibrosis accompanied by increased mortality with death as early as two weeks (Haghighi et al., 2006). These naturally occurring mutations in phospholamban have revealed the importance of the balance of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated phospholamban and its localization in the heart.

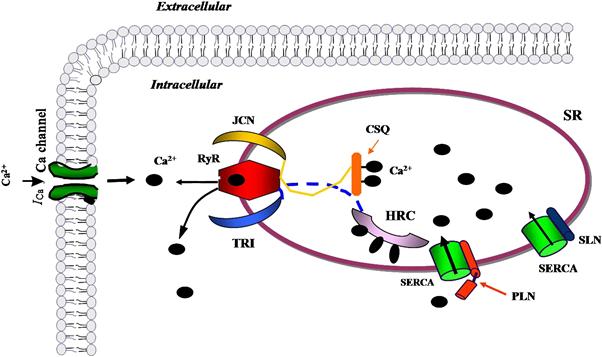

IID Other Regulators of the SR Ca2+-ATPase

While phospholamban is the primary regulator of SR Ca2+-ATPase activity, several other proteins have been identified that modulate the SR Ca2+ pump (Fig. 13.9). For example, sarcolipin, a homolog of phospholamban, has been shown to inhibit SERCA1a and SERCA2a; however, sarcolipin is expressed more abundantly in atria unlike phospholamban which is predominantly in the ventricle of the heart (Bhupathy et al., 2007). Overexpression of sarcolipin in mice resulted in reduced Ca2+ affinity of SERCA2a as well as decreased cardiac function which was improved by β-adrenergic stimulation in vivo (Bhupathy et al., 2007). Conversely, ablation of sarcolipin in mice resulted in elevated SR Ca2+ uptake and faster relaxation of the atria (Babu et al., 2007). The histidine-rich calcium binding protein (HRC), located in the SR, was shown to interact with SERCA2a in vitro in a Ca2+ sensitive manner with maximal binding occurring at low Ca2+ concentrations (Arvanitis et al., 2007). HRC also interacts with triadin, a protein that is part of the Ca2+ release quaternary complex; therefore, HRC can regulate both Ca2+ release uptake and release making it an interesting new molecule in SR Ca2+ handling. Indeed, acute overexpression of HRC decreased Ca2+ release and contractility in vitro while chronic overexpression reduced SR Ca2+ uptake and contractility in vivo (Fan et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2006). Moreover, HRC transgenic mice exhibited cardiac remodeling with aging (Gregory et al., 2006).

FIGURE 13.9 Schematic of regulators of SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) function. Phospholamban (PLN) is the primary regulator of the SR Ca2+ pump. Sarcolipin (SLN), a homolog of PLN, can also modulate SERCA activity and may be important to Ca2+ cycling in the atria where it is abundant. Histidine-rich Ca2+-binding protein (HRC) is an SR lumen protein that binds Ca2+ and has been shown to interact with SERCA and affect Ca uptake. HRC also interacts with triadin, a protein that is part of the Ca2+ release quaternary complex including the ryanodine receptor (RyR) and junctin (JCN).

IIE SR Ca2+-ATPase in Cardiac Diseases

The complex regulation of the SR function clearly indicates that even small disturbances in SR Ca2+ handling may result in profound changes and deterioration of normal myocardial function. The fast removal of Ca2+ by the SR Ca2+-ATPase during diastole and the subsequent rapid release through the SR Ca2+ channel (ryanodine receptor) at the beginning of contraction are prerequisites for normal diastolic and systolic function. We briefly outline in the next section the alterations in the SR Ca2+-ATPase in the major cardiac diseases.

IIE1 SR Ca2+-ATPase in Hyperthyroidism and Hypothyroidism

Thyroid hormones are important regulators of myocardial contractility and relaxation. Chronic increases in thyroid hormone levels lead to cardiac hypertrophy, with increases in the heart rate and cardiac output as well as left ventricular contractility and velocity of relaxation. On the other hand, opposite effects are associated with a hypothyroid condition. The mechanisms underlying these changes have been the subject of numerous investigations. It is assumed that in hypo- and hyperthyroid hearts the altered gene expression of the cardiac SR proteins and, hence, the changes in the intracellular Ca2+ transients, is the most important determinant of the altered myocardial function. It was shown that the velocity of ATP-dependent Ca2+ transport and the Ca2+-ATPase activity are specifically increased in SR vesicle preparations from hyperthyroid compared with euthyroid hearts (Beekman et al., 1989). Opposite changes were noted for hypothyroid animals compared with euthyroid ones (Beekman et al., 1989).

Examination of the steady-state mRNA levels of the cardiac SR Ca2+-ATPase and the ryanodine receptor revealed a significant increase (140–190%) in hyperthyroid and a marked decline (40–50%) in hypothyroid animals (Arai et al., 1991). The changes in mRNA levels for the Ca2+-ATPase in hypothyroid and hyperthyroid conditions also reflected changes in the protein amounts of the enzyme in these hearts (Kiss et al., 1994, 1998). Interestingly, in the case of phospholamban, the regulator of the Ca2+-ATPase, and calsequestrin, there was no coordinated regulation with respect to the Ca2+-ATPase. In fact, both the relative mRNA level and the protein content of phospholamban were reported to decrease in hyperthyroid animals, whereas there was no change noted in the calsequestrin mRNA level upon L-thyroxine treatment. In hypothyroid hearts, an opposite trend was noted since the protein amount of phospholamban was found to be increased as compared to the euthyroid or hyperthyroid animals (Kiss et al., 1994, 1998). Consequently, the phospholamban-Ca2+-ATPase protein ratio was highest in the hypothyroid animals, followed by euthyroid and hyperthyroid animals. These changes in the phospholamban-Ca2+-ATPase ratio were associated with coordinate alterations in the SR Ca2+ uptake, affinity of the SERCA2 for Ca2+ and myocardial function (Kiss et al., 1994; Kimura et al., 1994).

These changes indicate that the SR proteins responsible for Ca2+ uptake and release (Ca2+-ATPase and ryanodine receptor) are coordinately regulated in hypothyroid and hyperthyroid hearts and provide a simple explanation for the altered Ca2+ release and reuptake capacity and hence the myocardial function under these conditions.

IIE2 SR Ca2+-ATPase in Cardiomyopathies

Dilated cardiomyopathy is a frequent form of cardiac muscle disease and is characterized by an impaired systolic function and dilatation of both ventricles (systolic pump failure). In various animal models of primary and secondary dilated cardiomyopathy, it was shown that both SR Ca2+ binding capacity and uptake were depressed because of the decreased activity and protein level of the SR Ca2+-ATPase (Edes et al., 1991). In some studies of human idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, decreases were noted for both SR Ca2+ uptake rates and Ca2+-ATPase activity (Limas et al., 1987; Unverferth et al., 1988) as well as myocardial Ca2+ handling (Gwathmey et al., 1987; Beuckelmann et al., 1992). Examination of the mRNA levels in left ventricular biopsies from patients with dilated cardiomyopathy revealed a significant decrease in mRNA content for the SR Ca2+-ATPase relative to other mRNA forms (Mercadier et al., 1990; Arai et al., 1993). In contrast, other authors were unable to detect a decrease in SR Ca2+ uptake activity (Movsesian et al., 1989) or the immunodetectable levels of the SR Ca2+-ATPase protein (Schwinger et al., 1995) in the left ventricular myocardium from patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Furthermore, the gating mechanism of the SR Ca2+-release channel was reported to be abnormal in dilated cardiomyopathy (D’Agnolo et al., 1992; Sen et al., 2000), and it was suggested that defective excitation–contraction coupling is involved in the pathogenesis of this disease.

Another type of cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, has only been recognized in clinical practice for the last four decades. The characteristics of this disease are asymmetric interventricular septal hypertrophy and narrowing of the left ventricular outflow tract, with or without outflow obstruction (outflow tract pressure gradient). In the familial form of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which accounts for about 45–70% of all cases, mutations in myofibrillar protein genes (β-myosin heavy chain, troponin T, troponin I, α-tropomyosin and C protein among others) are associated with the disease (Ho, 2010). Additionally, prolongation of the Ca2+ transient, abnormal Ca2+ handling and a decline in SR Ca2+-ATPase mRNA levels are reported to be characteristic for human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Lipskaia et al., 2009), which may explain the diastolic function impairment in this disease.

In chronic heart failure due to hemodynamic overload, irrespective of the specific etiology (valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathy, chronic ischemic heart disease or hypertension), a reduction was observed in both the number and the activity of the SR Ca2+ pump (Limas et al., 1987; Unverferth et al., 1988). Furthermore, a close correlation was obtained between the SR Ca2+-ATPase mRNA or protein levels and the myocardial function (Gregory and Kranias, 2006). In addition, total phospholamban protein levels are unchanged in heart failure, but phosphorylated phospholamban levels are decreased further compounding reduced SR Ca2+-ATPase activity (Gregory and Kranias, 2006). Interestingly, the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger gene expression is increased in failing human hearts and it is hypothesized that the upregulation of this protein may compensate for the depressed SR function (Bers and Despa, 2006).

IIE3 SR Ca2+-ATPase in Ischemia

A brief period of ischemia (10–20 min) induces reversible tissue damage in cardiac muscle, resulting in a “stunned” myocardium. This condition is characterized by regional contractile abnormalities (declines in both systolic and diastolic function) that persist for several hours despite the absence of necrosis. These hemodynamic changes are associated with a reduction in SR Ca2+ transport (Krause et al., 1989; Limbruno et al., 1989). The maximal activity of the SR Ca2+-ATPase was found to be depressed and the Ca2+ sensitivity of this enzyme was decreased (Krause et al., 1989). Furthermore, a decrease in the coupling ratio (mol Ca2+/mol ATP) was observed in the SR membranes isolated from the stunned myocardium, which was suggested to be the result of an increase in the Ca2+ permeability of the SR membrane. The SR Ca2+-release process was also found to be impaired in the stunned myocardium due to a reduction of the number of ryanodine receptors (Zucchi et al., 1994). These data suggest that complex modifications of the SR function occur in the stunned myocardium, which are at least partly responsible for the contractile impairment found in this condition.

In long-lasting myocardial ischemia, gradual declines in both SR Ca2+-ATPase activity and Ca2+ uptake were found, which may be due to decreased SR Ca2+-ATPase protein (Talukder et al., 2009). Increasing SERCA2a via gene transfer or transgenic overexpression is cardioprotective against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Ischemia was also shown to result in variable changes in the phosphorylation of phospholamban (Talukder et al., 2009). Thus, the role of phospholamban regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in ischemia is not resolved. A combination of various pathogenic factors has been suggested to be responsible for the reduced SR function and the final tissue necrosis in the ischemic myocardium. These pathological factors include pH reduction (acidosis), activation of intracellular proteolytic enzymes, and increased generation of free radicals.

IIE4 SR Ca2+-ATPase as a Target for Heart Failure Treatment

Given the central importance of the SR Ca2+-ATPase to proper SR Ca2+ cycling, excitation–contraction coupling and thus cardiac function, SERCA2 has been a focus of potential gene-targeted therapy for heart failure, especially since pump activity is depressed in failing hearts. SERCA2a gene transfer in animal models and human failing cardiomyocytes has shown beneficial effects, including improved contractility and energetics as well as prevention of arrhythmias and hypertrophy. For example, adenoviral delivery of SERCA2a to human failing cardiomyocytes rescued the depressed contractility and Ca2+ transients (reviewed in Lipskaia et al., 2010). Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer also improved function and survival in rat failing hearts. Additionally, SERCA2a delivery suppressed arrhythmias as well as infarct size in a rat model of ischemia/reperfusion injury (reviewed in Lipskaia et al., 2010). These beneficial effects in heart failure have also been demonstrated in large animals (reviewed in Lipskaia et al., 2010).

III Other ATPases

The Ca2+ regulation in eukaryotic cells involves a complex mechanism that maintains a low background Ca2+ concentration (usually 0.1–0.2 μM) in the cell interior. Eukaryotic cells generally satisfy their Ca2+ demands by extracting Ca2+ from their own internal stores, but it is also evident that the long-term regulation of the Ca2+ gradient across the plasma membrane is a result of the concerted operation of the importing (Ca2+ channel) and exporting (SR Ca2+ pump; Na+-Ca2+exchanger and Ca2+ pump of the surface membrane) Ca2+ systems. The plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase is a low-capacity system possessing a very high Ca2+ affinity, which enables the enzyme to interact with Ca2+ at low intracellular concentrations. Consequently, its function is continuous and presumably satisfies the fine tuning of Ca2+ homeostasis.

IIIA General Properties of Plasma Membrane Ca2+-ATPase(s)

The plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (molecular mass of 140 kDa) general kinetic mechanism follows the pattern of the SR Ca2+-ATPase. ATP phosphorylates an Asp residue to yield an acid-stable phosphorylated intermediate. The elementary steps of the cycle are probably similar in both SR and plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPases (Schatzmann, 1989). The stoichiometry between transported Ca2+ and hydrolyzed ATP is only 1.0 for the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump. The administration of La3+ under various experimental conditions has been associated with an increase in the steady-state phosphoenzyme level of the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase and this increase possibly results from stabilization of the aspartyl phosphate (inhibition of hydrolysis of the phosphate group). The other classic inhibitor of Ca2+ pumps, vanadate, has been found to be a potent inhibitor of the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (Brini and Carafoli, 2009).

Calmodulin stimulates the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase by direct interaction with the enzyme. It has been shown that the stimulation results from a combined effect on the affinity for Ca2+ (Km) and the maximal transport rate (Vmax) (Brini and Carafoli, 2009). The calmodulin-binding domain of the Ca2+ pump has been suggested to function as a repressor of the enzymatic activity (autoinhibitory function) and calmodulin may relieve this inhibition (Brini and Carafoli, 2009). A common mechanism in the autoinhibition of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase and phospholamban inhibition of SR Ca2+-ATPase has been suggested. In both proteins, the interacting sites are amphiphilic and located in the cytoplasmic region. The interaction occurs with homologous regions in the SR and plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPases close to the phosphorylation sites. In the absence of calmodulin, the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump can be activated by several other compounds. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and acidic phospholipids (phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-diphosphate) have been reported to be good activators and, since they are present in the plasma membrane, they may be important regulators of the Ca2+-ATPase under in vivo conditions (Brini and Carafoli, 2009). Phosphorylation of the enzyme by cAMP-dependent PK or PK-C has also been reported to stimulate plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase activity. The cAMP-dependent phosphorylation occurs C-terminally to the calmodulin-binding domain and the phosphorylation-mediated activation may likewise be significant in vivo. The PK-C phosphorylation occurs in the calmodulin-binding domain, inhibiting the binding of calmodulin to the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase and lowering the autoinhibitory potential of this domain (Brini and Carafoli, 2009). Cyclic GMP–dependent PK has also been reported to stimulate the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump in vascular smooth muscle, but the Ca2+-ATPase enzyme was not found to be the substrate for this kinase.

IIIB Primary Structure and Topography of Plasma Membrane Ca2+-ATPase(s)

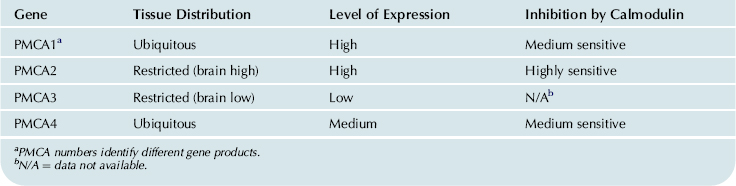

The complete amino acid sequence of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump has been deduced from rat and human cells (Shull and Greeb, 1988; Verma et al., 1988). It appears that four plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA 1–4) isoforms are encoded by a multigene family and additional variability is produced by alternative RNA splicing of each gene transcript (Table 13.2). The regions important for the catalytic function and the transmembrane domains are highly conserved, with no observed diversity. The isoform diversity seems to alter primarily the regulatory characteristics of the enzyme and it can be regarded as an adaptation to tissue specificity.

TABLE 13.2. Distribution of the Human Plasma Membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) Isoforms

The secondary structure of the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase is similar to that of the SR Ca2+-ATPase (Shull and Greeb, 1988). The enzyme contains 10 putative transmembrane helices, which are connected on the outside of the plasma membrane by short loops. Three primary domains (about 80% of the pump protein) protrude into the cytoplasm. The first domain corresponds to the transducing unit, which couples ATP hydrolysis to Ca2+ translocation. The second protruding domain contains the aspartyl phosphate site (phosphorylation domain). The C-terminal portion of this domain can also be labeled by ATP analogs and contains a “hinge” region that permits the movement of aspartyl phosphate and the ATP-binding site. The third C-terminal protruding domain contains the calmodulin-binding sequence and the phosphorylation sites for protein kinase C and cAMP-dependent protein kinase. The latter is not present in all isoforms. As in the SR Ca2+-ATPase, selective mutations in the M4 and M6 transmembrane segments in the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase have been associated with loss of its ability to form the ATP- and Ca2+-dependent phosphorylated intermediate and to transport Ca2+ (Guerini et al., 1998).

IIIC Isoform-Specific Function of the Plasma Membrane Ca2+-ATPase

While there is no specific inhibitor of the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA), the use of gene-altered mouse models has provided insights into the function of specific isoforms of the pump. Ablation of the PMCA1 gene in mice is lethal, suggesting its importance in a housekeeping function (Okunade et al., 2004). However, ablation of PMCA2 does not result in lethality, but mice have a reduction in spinal cord motor neurons, hearing loss and abnormalities in balance control. The deafness in PMCA2 null mice is related to a loss of otoconia and pathology of the auditory system. The PMCA2 isoform is also involved in lactation as PMCA2 null mice had a decrease in the Ca2+ levels in the milk (reviewed in Brini and Carafoli, 2009). PMCA4 homozygous null mice are also viable, but male mice are infertile due to reduced sperm motility (Okunade et al., 2004). No mouse model of PMCA3 ablation has been generated yet, thus the functional importance of this isoform is not currently clear. These studies indicate that the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase is essential for maintaining various processes in a variety of cell types and there are different functional roles for the various isoforms.

IV Overview

The Ca2+ levels in muscle are primarily regulated by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) network, which serves as a sink for Ca2+ ions during relaxation and as a Ca2+ source during contraction. In cardiac muscle, most of the intracellular Ca2+ released during systole is taken up by the SR through its Ca2+-ATPase. This translocation of Ca2+ from the cytosol into the SR lumen uses ATP as the energy source, and is characterized by the formation of a phosphorylated intermediate (E1~P) for the Ca2+-ATPase.

In cardiac muscle, slow-twitch skeletal muscle and smooth muscle, the Ca2+-ATPase is regulated by a low-molecular-weight phosphoprotein called phospholamban. In its dephosphorylated form, phospholamban is an inhibitor of the Ca2+-ATPase and phosphorylation relieves this inhibition. Phosphorylation of phospholamban occurs by cAMP-dependent, cGMP-dependent, Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent, and Ca2+-phospholipid-dependent protein kinases in vitro. However, in vivo studies have indicated that phospholamban is phosphorylated only by cAMP-dependent and Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinases in intact beating hearts. A phospholamban phosphatase activity has been reported to be present in SR membranes, which can dephosphorylate this regulatory protein and reverse its stimulatory effects on the Ca2+-ATPase.

Alterations in the SR Ca2+-ATPase activity and its regulation by phospholamban have been shown to occur in cardiac diseases such as hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, hypertrophy, heart failure and ischemia. In most instances, alterations in Ca2+-ATPase activity correlated with alterations in its mRNA levels and ventricular function. Recent studies have supported the targeting of the SR Ca2+-ATPase as a therapeutic modality in cardiomyopathy and heart failure.

Another Ca2+-ATPase, which is also important for maintaining Ca2+ homeostasis in muscle, is the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase. This enzyme transports Ca2+ to the extracellular space and uses ATP as its energy source, similar to the SR Ca2+-ATPase. The plasmalemmal Ca2+-ATPase may be distinguished from the SR Ca2+-ATPase primarily by its distinct sensitivity to La3+, vanadate and calmodulin.

The primary structure of the various Ca2+ pumps has been elucidated and efforts are underway to further understanding the structural–functional relationships of these enzymes under pathological conditions. Furthermore, there is a growing interest in uncovering the mechanisms underlying regulation of the Ca2+-ATPases by key endogenous proteins.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ research discussed in this chapter was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-26057, HL-64018 and HL007382 training grant. This article was published in Cell Physiology Sourcebook 3rd edn, I. Edes and E.G. Kranias, eds (2001), Ch. 18, Ca2+-ATPases, pp. 271-282. Copyright Elsevier, Inc.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Arai M, Alpert NR, MacLennan DH, Barton P, Periasamy M. Alterations in sarcoplasmic reticulum gene expression in human heart failure A possible mechanism for alterations in systolic and diastolic properties of the failing myocardium. Circ Res. 1993;72:463–469.

2. Arai M, Otsu K, MacLennan DH, Alpert NR, Periasamy M. Effect of thyroid hormone on the expression of mRNA encoding sarcoplasmic reticular proteins. Circ Res. 1991;69:266–276.

3. Arvanitis DA, Vafiadaki E, Fan GC, et al. Histidine-rich Ca-binding protein interacts with sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1581–H1589.

4. Babu GJ, Bhupathy P, Timofeyev V, et al. Ablation of sarcolipin enhances sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium transport and atrial contractility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:17867–17872.

5. Baker DL, Hashimoto K, Grupp IL, et al. Targeted overexpression of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase increases cardiac contractility in transgenic mouse hearts. Circ Res. 1998;83:1205–1214.

6. Beekman RE, van Hardeveld C, Simonides WS. On the mechanism of the reduction by thyroid hormone of β-adrenergic relaxation rate stimulation in rat heart. Biochem J. 1989;259:229–236.

7. Bers DM. Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:23–49.

8. Bers DM, Despa S. Cardiac myocytes Ca2+ and Na+ regulation in normal and failing hearts. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;100:315–322.

9. Beuckelmann DJ, Nabauer M, Erdmann E. Intracellular calcium handling in isolated ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. Circulation. 1992;85:1046–1055.

10. Bhupathy P, Babu GJ, Periasamy M. Sarcolipin and phospholamban as regulators of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:903–911.

11. Brini M, Carafoli E. Calcium pumps in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:1341–1378.

12. Brittsan AG, Carr AN, Schmidt AG, Kranias EG. Maximal inhibition of SERCA2 Ca2+ affinity by phospholamban in transgenic hearts overexpressing a non-phosphorylatable form of phospholamban. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12129–12135.

13. Chu G, Lester JW, Young KB, Luo W, Zhai J, Kranias EG. A single site (Ser16) phosphorylation in phospholamban is sufficient in mediating its maximal cardiac responses to β-agonists. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38938–38943.

14. D’Agnolo A, Luciani GB, Mazzucco A, Gallucci V, Salviati G. Contractile properties and Ca2+ release activity of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1992;85:518–525.

15. Dally S, Corvazier E, Bredoux R, Bobe R, Enouf J. Multiple and diverse coexpression, location, and regulation of additional SERCA2 and SERCA3 isoforms in nonfailing and failing human heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:633–644.

16. Edes I, Kranias EG. Phospholamban and troponin I are substrates for protein kinase C in vitro but not in intact beating guinea pig hearts. Circ Res. 1990;67:394–400.

17. Edes I, Talosi L, Kranias E. Sarcoplasmic reticulum function in normal heart and in cardiac disease. Heart Failure. 1991;6:221–237.

18. Fan GC, Gregory KN, Zhao W, Park WJ, Kranias EG. Regulation of myocardial function by histidine-rich, calcium-binding protein. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1705–H1711.

19. Fujii J, Zarain-Herzberg A, Willard HF, Tada M, MacLennan DH. Structure of the rabbit phospholamban gene, cloning of the human cDNA, and assignment of the gene to human chromosome 6. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11669–11675.

20. Gianni D, Chan J, Gwathmey JK, del Monte F, Hajjar RJ. SERCA2a in heart failure: role and therapeutic prospects. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2005;37:375–380.

21. Gregory KN, Kranias EG. Targeting sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium handling proteins as therapy for cardiac disease. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2006;47:132–143.

22. Gregory KN, Ginsburg KS, Bodi I, et al. Histidine-rich Ca binding protein: a regulator of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium sequestration and cardiac function. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:653–665.

23. Guerini D, Garcia-Martin E, Zecca A, Guidi F, Carafoli E. The calcium pump of the plasma membrane: membrane targeting, calcium binding sites, tissue-specific isoform expression. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1998;643:265–273.

24. Gwathmey JK, Copelas L, MacKinnon R, et al. Abnormal intracellular calcium handling in myocardium from patients with end-stage heart failure. Circ Res. 1987;61:70–76.

25. Haghighi K, Kolokathis F, Gramolini AO, et al. A mutation in the human phospholamban gene, deleting arginine 14, results in lethal, hereditary cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1388–1393.

26. Haghighi K, Kolokathis F, Pater L, et al. Human phospholamban null results in lethal dilated cardiomyopathy revealing a critical difference between mouse and human. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:869–876.

27. Haghighi K, Schmidt AG, Hoit BD, et al. Superinhibition of sarcoplasmic reticulum function by phospholamban induces cardiac contractile failure. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24145–24152.

28. Ho CY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail Clin. 2010;6:141–159.

29. Hoit BD, Khoury SF, Kranias EG, Ball N, Walsh RA. In vivo echocardiographic detection of enhanced left ventricular function in gene-targeted mice with phospholamban deficiency. Circ Res. 1995;77:632–637.

30. Huggins JP, Cook EA, Piggott JR, Mattinsley TJ, England PJ. Phospholamban is a good substrate for cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase in vitro, but not in intact cardiac or smooth muscle. Biochem J. 1989;260:829–835.

31. Ji Y, Lalli MJ, Babu GJ, et al. Disruption of a single copy of the SERCA2 gene results in altered Ca2+ homeostasis and cardiomyocyte function. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38073–38080.

32. Kadambi VJ, Ponniah S, Harrer JM, et al. Cardiac-specific overexpression of phospholamban alters calcium kinetics and resultant cardiomyocyte mechanics in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:533–539.

33. Kim HW, Steenaart NA, Ferguson DG, Kranias EG. Functional reconstitution of the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase with phospholamban in phospholipid vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1702–1709.

34. Kimura Y, Otsu K, Nishida K, Kuzuya T, Tada M. Thyroid hormone enhances Ca2+ pumping activity of the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum by increasing Ca2+ ATPase and decreasing phospholamban expression. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1994;26:1145–1154.

35. Kiss E, Brittsan AG, Edes I, Grupp IL, Kranias EG. Thyroid hormone-induced alterations in phospholamban-deficient mouse hearts. Circ Res. 1998;83:608–613.

36. Kiss E, Jakab G, Kranias EG, Edes I. Thyroid hormone-induced alterations in phospholamban protein expression regulatory effects on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transport and myocardial relaxation. Circ Res. 1994;75:245–251.

37. Kranias EG, Solaro RJ. Phosphorylation of troponin I and phospholamban during catecholamine stimulation of rabbit heart. Nature. 1982;298:182–184.

38. Kranias EG, Garvey JL, Srivastava RD, Solaro RJ. Phosphorylation and functional modifications of sarcoplasmic reticulum and myofibrils in isolated rabbit hearts stimulated with isoprenaline. Biochem J. 1985;226:113–121.

39. Krause SM, Jacobus WE, Becker LC. Alterations in cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium transport in the postischemic "stunned" myocardium. Circ Res. 1989;65:526–530.

40. Limas CJ, Olivari MT, Goldenberg IF, Levine TB, Benditt DG, Simon A. Calcium uptake by cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum in human dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 1987;21:601–605.

41. Limbruno U, Zucchi R, Ronca-Testoni S, Galbani P, Ronca G, Mariani M. Sarcoplasmic reticulum function in the "stunned" myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989;21:1063–1072.

42. Lindemann JP, Watanabe AM. Muscarinic cholinergic inhibition of β-adrenergic stimulation of phospholamban phosphorylation and Ca2+ transport in guinea pig ventricles. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:122–133.

43. Lindemann JP, Watanabe AM. Phosphorylation of phospholamban in intact myocardium Role of Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:4516–4525.

44. Lindemann JP, Jones LR, Hathaway DR, Henry BG, Watanabe AM. β-adrenergic stimulation of phospholamban phosphorylation and Ca2+-ATPase activity in guinea pig ventricles. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:464–471.

45. Lipskaia L, Chemaly ER, Hadri L, Lompre A, Hajjar RJ. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase as a therapeutic target for heart failure. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:29–41.

46. Lipskaia L, Hulot JS, Lompre AM. Role of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium content and calcium ATPase activity in the control of cell growth and proliferation. Pflugers Arch. 2009;457:673–685.

47. Liu LH, Boivin GP, Prasad V, Prasad V, Periasamy M, Shull GE. Squamous cell tumors in mice heterozygous for a null allele of Atp2a2, encoding the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase isoform 2 Ca2+ pump. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26737–26740.

48. Liu LH, Paul RJ, Sutliff RL, et al. Defective endothelium-dependent relaxation of vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cell Ca2+ signaling in mice lacking sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase isoform 3. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30538–30545.

49. Lorenz JN, Kranias EG. Regulatory effects of phospholamban on cardiac function in intact mice. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H2826–H2831.

50. Loukianov E, Ji Y, Grupp IL, et al. Enhanced myocardial contractility and increased Ca2+ transport function in transgenic hearts expressing the fast-twitch skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Circ Res. 1998;83:889–897.

51. Luo W, Chu G, Sato Y, Zhou Z, Kadambi VJ, Kranias EG. Transgenic approaches to define the functional role of dual site phospholamban phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4734–4739.

52. Luo W, Grupp IL, Harrer J, et al. Targeted ablation of the phospholamban gene is associated with markedly enhanced myocardial contractility and loss of β-agonist stimulation. Circ Res. 1994;75:401–409.

53. Luo W, Wolska BM, Grupp IL, et al. Phospholamban gene dosage effects in the mammalian heart. Circ Res. 1996;78:839–847.

54. MacLennan DH, Abu-Abed M, Kang C. Structure–function relationships in Ca2+ cycling proteins. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:897–918.

55. MacLennan DH, Kimura Y, Toyofuku T. Sites of regulatory interaction between calcium ATPases and phospholamban. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;853:31–42.

56. Mattiazzi A, Mundina-Weilenmann C, Guoxiang C, Vittone L, Kranias EG. Role of phospholamban phosphorylation on Thr17 in cardiac physiological and pathological conditions. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:366–375.

57. Mercadier JJ, Lompre AM, Duc P, et al. Altered sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase gene expression in the human ventricle during end-stage heart failure. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:305–309.

58. Møller JV, Nissen P, Sorensen TL, le Maire M. Transport mechanism of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ -ATPase pump. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:387–393.

59. Morris GL, Cheng HC, Colyer J, Wang JH. Phospholamban regulation of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum (Ca2+-Mg2+)-ATPase Mechanism of regulation and site of monoclonal antibody interaction. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11270–11275.

60. Mortishire-Smith RJ, Pitzenberger SM, Burke CJ, Middaugh CR, Garsky VM, Johnson RG. Solution structure of the cytoplasmic domain of phopholamban: phosphorylation leads to a local perturbation in secondary structure. Biochemistry. 1995;34:7603–7613.

61. Movsesian MA, Bristow MR, Krall J. Ca2+ uptake by cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum from patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 1989;65:1141–1144.

62. Odermatt A, Taschner PE, Khanna VK, et al. Mutations in the gene-encoding SERCA1, the fast-twitch skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase, are associated with Brody disease. Nat Genet. 1996;14:191–194.

63. Okunade GW, Miller ML, Pyne GJ, et al. Targeted ablation of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) 1 and 4 indicates a major housekeeping function for PMCA1 and a critical role in hyperactivated sperm motility and male fertility for PMCA4. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33742–33750.

64. Pan Y, Zvaritch E, Tupling AR, et al. Targeted disruption of the ATP2A1 gene encoding the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase isoform 1 (SERCA1) impairs diaphragm function and is lethal in neonatal mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13367–13375.

65. Periasamy M, Reed TD, Liu LH, et al. Impaired cardiac performance in heterozygous mice with a null mutation in the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase isoform 2 (SERCA2) gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2556–2562.

66. Reddy LG, Jones LR, Pace RC, Stokes DL. Purified, reconstituted cardiac Ca2+-ATPase is regulated by phospholamban but not by direct phosphorylation with Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14964–14970.

67. Sakuntabhai A, Ruiz-Perez V, Carter S, et al. Mutations in ATP2A2, encoding a Ca2+ pump, cause Darier disease. Nat Genet. 1999;21:271–277.

68. Schatzmann HJ. The calcium pump of the surface membrane and of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Physiol. 1989;51:473–485.

69. Schmidt AG, Zhai J, Carr AN, et al. Structural and functional implications of the phospholamban hinge domain: impaired SR Ca2+ uptake as a primary cause of heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;56:248–259.

70. Schmitt JP, Kamisago M, Asahi M, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure caused by a mutation in phospholamban. Science. 2003;299:1410–1413.

71. Schultz Jel J, Glascock BJ, Witt SA, et al. Accelerated onset of heart failure in mice during pressure overload with chronically decreased SERCA2 calcium pump activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;286:H1146–H1153.

72. Schwinger RH, Bohm M, Schmidt U, et al. Unchanged protein levels of SERCA II and phospholamban but reduced Ca2+ uptake and Ca2+-ATPase activity of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum from dilated cardiomyopathy patients compared with patients with nonfailing hearts. Circulation. 1995;92:3220–3228.

73. Sen L, Cui G, Fonarow GC, Laks H. Differences in mechanisms of SR dysfunction in ischemic vs idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H709–H718.

74. Sharma P, Ignatchenko V, Grace K, Ursprung C, Kislinger T, Gramolini AO. Endoplasmic reticulum protein targeting of phospholamban: a common role for an N-terminal di-arginine motif in ER retention?. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11496.

75. Shull GE, Greeb J. Molecular cloning of two isoforms of the plasma membrane Ca2+-transporting ATPase from rat brain Structural and functional domains exhibit similarity to Na+, K+- and other cation transport ATPases. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:8646–8657.

76. Simmerman HK, Jones LR. Phospholamban: protein structure, mechanism of action, and role in cardiac function. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:921–947.

77. Talosi L, Edes I, Kranias EG. Intracellular mechanisms mediating reversal of β-adrenergic stimulation in intact beating hearts. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:H791–H797.

78. Talukder MA, Zweier JL, Periasamy M. Targeting calcium transport in ischaemic heart disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;84:345–352.

79. Toyofuku T, Curotto Kurzydlowski K, Narayanan N, MacLennan DH. Identification of Ser38 as the site in cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase that is phosphorylated by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26492–26496.

80. Unverferth DV, Lee SW, Wallick ET. Human myocardial adenosine triphosphatase activities in health and heart failure. Am Heart J. 1988;115:139–146.

81. Ver Heyen M, Heymans S, Antoons G, et al. Replacement of the muscle-specific sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase isoform SERCA2a by the nonmuscle SERCA2b homologue causes mild concentric hypertrophy and impairs contraction–relaxation of the heart. Circ Res. 2001;89:838–846.

82. Verma AK, Filoteo AG, Stanford DR, et al. Complete primary structure of a human plasma membrane Ca2+ pump. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:14152–14159.

83. Wolska BM, Stojanovic MO, Luo W, Kranias EG, Solaro RJ. Effect of ablation of phospholamban on dynamics of cardiac myocyte contraction and intracellular Ca2+. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C391–C397.

84. Zhai J, Schmidt AG, Hoit BD, Kimura Y, MacLennan DH, Kranias EG. Cardiac-specific overexpression of a superinhibitory pentameric phospholamban mutant enhances inhibition of cardiac function in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10538–10544.

85. Zhao W, Uehara Y, Chu G, et al. Threonine-17 phosphorylation of phospholamban: a key determinant of frequency-dependent increase of cardiac contractility. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:607–612.

86. Zucchi R, Ronca-Testoni S, Yu G, Galbani P, Ronca G, Mariani M. Effect of ischemia and reperfusion on cardiac ryanodine receptors–sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ channels. Circ Res. 1994;74:271–280.

87. Zvaritch E, Backx PH, Jirik F, et al. The transgenic expression of highly inhibitory monomeric forms of phospholamban in mouse heart impairs cardiac contractility. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14985–14991.