Chapter 16

Osmosis and Regulation of Cell Volume

Chapter Outline

III. Water Movement Across Model Membranes

IIIC. Thermodynamic Derivation of van’t Hoff’s Law

IIID. Other Colligative Properties of Solutions

IIIE. Osmotic Pressure of Non-ideal Solutions

IVA1. Osmotic and Pressure-Driven Flow through Porous Membranes

IVA2. Diffusional Permeability of Porous Membranes: Pd

IVA3. Evidence for Pores: Pf/Pd Ratio

IVA4. Physical Origin of Osmotic Pressure

IVA5. Physical Interpretation of the Reflection Coefficient, σ

IVB. Lipid Bilayer Membranes: the Dissolution–Diffusion Model

IVB1. Osmotic and Pressure-Driven Flow for the Dissolution-Diffusion Model: Pf

IVB2. Diffusional Water Permeability through Lipid Membranes: Pd

IVB3. Pf/Pd Ratio for the Dissolution–Diffusion Model

IVC. Flow through Narrow Pores: Pf/Pd Ratio

IVD. Mechanism of Water Transport across Lipid Bilayer Membranes

V. Water Movement Across Cell Membranes

VA. Rate of Water Exchange: Experimental Measure of Pd

VB. Rate of Osmotic Flow: Experimental Measure of Pf and Lp

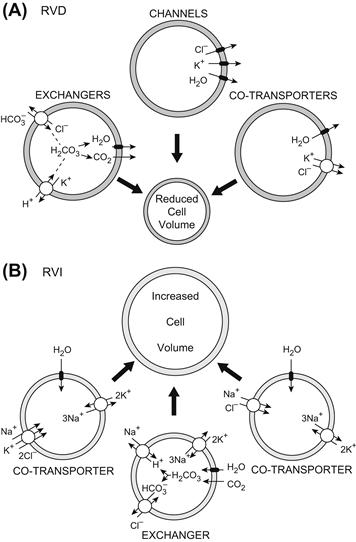

VI. Regulation of Cell Volume under Isosmotic Conditions

I Summary

The study of mechanisms underlying osmosis and the regulation of cell volume under both isosmotic and anisosmotic conditions has been fruitful. We understand in substantial detail how water and ions cross the membrane. Where do we go from here? Many directions are possible and as many details are missing as are known. For example, the identification and cloning of water channels raise several important questions. What is it about the protein structure that makes this a water channel? How does water interact with the channel? From a theoretical perspective, how is osmotic pressure sensed and how does osmosis occur through a channel structure that is different in important ways from the well-explored hydrodynamic models? From the perspective of regulation of ion transport, much remains to be understood about how cells sense swelling and shrinking and how a cell decides on its optimal volume. There are also unanswered questions concerning the regulation of volume regulatory ion transporters by cellular messengers, metabolic demands and pathological states. In short, we can look forward to many more fruitful years of research on these topics.

II Introduction

In whole blood, erythrocytes are biconcave disks about 7 μm in diameter and 2 μm thick. When diluted in a solution of 0.9% NaCl (w/v), erythrocytes retain this shape. When diluted with higher concentrations of salt, the erythrocytes shrink, appearing as spheres with spikes all over their surface. These cells are described as crenated. If erythrocytes are diluted with a markedly lower concentration of salt, the cells swell. They first become spherical and then, if the solution is sufficiently low in salt, the cells burst and release their contents. These simple observations give rise to the concept of tonicity. Tonicity is operationally defined as the ability of a solution to shrink or swell specified cells. Thus, an isotonic solution induces no volume change when placed in contact with the cells. The tonicity of the solution is equal to the tonicity of the cell’s contents. Hypertonic solutions shrink cells, whereas hypotonic solutions increase cell volume. A solution that is isotonic for one type of cell may or may not be isotonic for others.

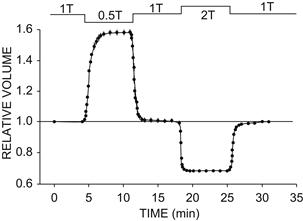

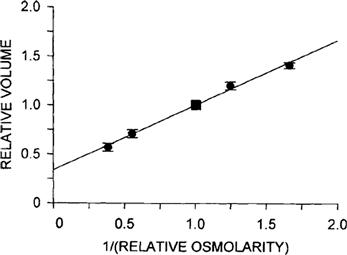

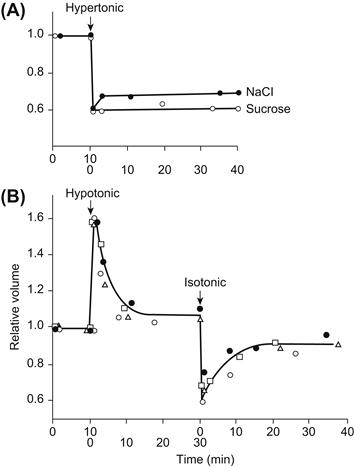

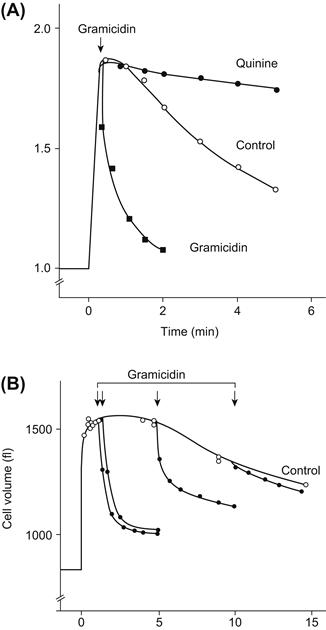

All animal cells shrink or swell on exposure to anisotonic solutions. Figure 16.1 shows the volume response of single isolated heart cells on exposure to hypertonic or hypotonic solutions. In hypotonic solution, myocytes swelled to more than 1.5 times their initial volume. The swelling was complete within 2 min, the new volume was stable and volume returned to normal upon return of the isotonic solution. In hypertonic solution, cell volume decreased to about 0.65 times normal and the original volume was restored upon return of the isotonic solution.

FIGURE 16.1 Response of isolated rabbit ventricular myocytes to osmotic stress. Cell volume was initially measured in isotonic solution (1T). Myocytes rapidly swelled 58% in a hypotonic solution with an osmolarity 0.5 times that of 1T and rapidly shrank 33% in a hypertonic solution with an osmolarity two times that of 1T. Cell volume was stable for the duration of perfusion with either hypotonic or hypertonic media and rapidly returned to its control value when 1T solution was readmitted. Volume was measured by digital video microscopy, and relative volume was calculated as volumetest/volume1T. Solution osmolarity was adjusted by varying the concentration of mannitol. (From Suleymanian and Baumgarten (1996). Reproduced from The Journal of General Physiology, 1996, 107, 503–514, by copyright permission of The Rockefeller University Press.)

The data in Fig. 16.1 show that volume changes in anisotonic media are very rapid. What is moving when the cells swell or shrink? What routes do these substances take? Are there homeostatic mechanisms that limit swelling and shrinking? If so, how are the compensatory mechanisms engaged? The answers to these questions are not yet complete. The purpose of this chapter is to provide the basis for understanding regulation of cell volume through the exchange of water and solutes across the plasma membrane.

III Water Movement Across Model Membranes

IIIA. Definition of Osmosis

Osmosis refers to the movement of fluid across a membrane in response to differing concentrations of solutes on the two sides of the membrane. Osmosis has been used since antiquity to preserve foods by dehydration with salt or sugar. The removal of water from a tissue by salt was referred to as imbibition. This description comes from the notion that these solutes attracted water from material they touched. In 1748, J.A. Nollet used an animal bladder to separate chambers containing water and wine. He noted that the volume in the wine chamber increased and, if this chamber was closed, a pressure developed. He named the phenomenon osmosis from the Greek ωσμoς, meaning thrust or impulse.

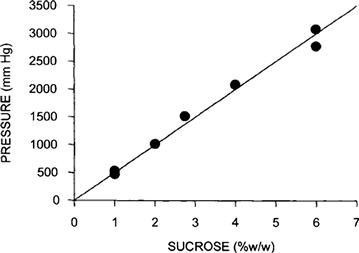

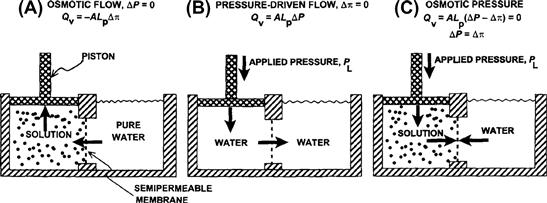

Pfeffer (1877) provided early quantitative observations on osmosis. He made an artificial membrane in the walls of an unglazed porcelain vessel by reacting copper salts with potassium ferrocyanide to form a copper ferrocyanide precipitation membrane on the surface of the vessel. He used this membrane to separate a sucrose solution inside the vessel from water outside and found a volume flow from the water side to the sucrose side. Pfeffer observed that the flow was proportional to the sucrose concentration. Further, a pressure applied inside the vessel produced a filtration flow proportional to the pressure. He found that a closed vessel containing a sucrose solution would develop a pressure proportional to the concentration of sucrose. He recognized this as an equilibrium state in which the pressure balanced the osmosis caused by the sucrose solution. Pfeffer’s original data for the osmotic pressure of sucrose solutions are plotted in Fig. 16.2. He defined osmotic pressure as the hydrostatic pressure necessary to stop osmotic flow across a barrier (e.g. a membrane) that is impermeable to the solute. This concept is illustrated in Fig. 16.3. Osmotic pressure is a property intrinsic to the solution and is measured at equilibrium, when the pressure-driven flow exactly balances the osmotic-driven flow. By defining osmotic pressure in this way, we assign a positive value to an apparent reduction in pressure brought about by dissolving the solute. Thus, fluid movement occurs from the solution of low osmotic pressure (water) to the solution of high osmotic pressure, opposite in direction to the hydraulic flow of water from high to low hydrostatic pressure.

FIGURE 16.2 Plot of data from Pfeffer (1877) for the osmotic pressure of sucrose solutions. A copper ferrocyanide precipitation membrane was formed in the walls of an unglazed porcelain cup. The membrane separated a sucrose solution in the inner chamber from water in the outer chamber. The inner chamber was then attached to a manometer and sealed. The linear relation between the pressure measured with this device and the sucrose concentration were the experimental impetus for deriving van’t Hoff’s law.

FIGURE 16.3 Equivalence of hydrostatic and osmotic pressures in driving fluid flow across a membrane. (A) An ideal, semipermeable membrane is freely permeable to water, but is impermeable to solute. When the membrane separates pure water on the right from solution on the left, water moves to the solution side. This water flow is osmosis. The flow, Qv, in cm3·s−1, is linearly related to the difference in osmotic pressure, Δπ, by the area of the membrane, A, and the hydraulic conductivity, Lp. Positive Qv is taken as flow to the right. The flow causes expansion of the left compartment and movement of the piston (which is assumed to be weightless). (B) Application of a pressure, PL, to the left compartment forces water out of this compartment, across the semipermeable membrane. The flow is linearly related to the pressure difference between the two compartments. (C) Application of a PL so that ΔP = Δπ results in no net flow across the membrane. The osmotic pressure of a solution is defined as the pressure necessary to stop water movement when the ideal, semipermeable membrane separates water from the solution.

An ideal semipermeable membrane is required for determining osmotic pressure. These membranes are permeable to water but absolutely impermeable to solute. The concept of osmotic pressure differs from tonicity in that tonicity compares two solutions separated by a specific non-ideal membrane. If the membrane is highly permeable to solute as well as to water, no water flow will occur and, therefore, the externally applied pressure required to stop osmosis is zero. This observation makes it plain that the effective osmotic pressure, which is measured with a real membrane, must be due to some interaction of the membrane with the solute because pressure depends on both the specific solute and the specific membrane.

IIIB van’t Hoff’s Law

From Pfeffer’s data and thought experiments considering gases in equilibrium with water, van’t Hoff (1887) argued that the osmotic pressure should be given by:

(16.1)

(16.1)

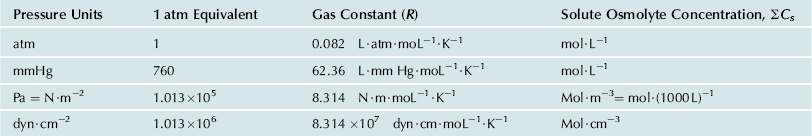

where π is the usual symbol for osmotic pressure, R is the gas constant, T is the temperature in kelvins, and Cs is the concentration of solute particles in solution. This equation is known as van’t Hoff’s law. Table 16.1 lists common units for osmotic pressure along with the values and units of R and Cs needed to make the calculation.

TABLE 16.1. Units for Calculation of Osmotic Pressure

Osmolarity (osmol·L−1) is defined as the concentration of osmotically active particles, osmolytes, in mol·L−1. Therefore, the units osmoles and moles cancel in the calculation of osmotic pressure.

The concentration used in van’t Hoff’s law, ΣCs, refers to the number of osmotically active particles that are formed upon dissolution of the solute. For example, organic compounds such as glucose ideally yield one particle, whereas strong salts such as NaCl or CaCl2 ideally yield two (Na+ and Cl−) or three (Ca2+ and two Cl−) particles. The osmolarity of a solution equals ΣCs and is expressed in osmol per liter to indicate that we are referring to the number of osmotically active particles, termed osmolytes, rather than the concentration of the solute. An alternative scale, osmolality, defines ΣCs per kilogram of solvent. Although the osmolal scale better describes the osmotic pressure in van’t Hoff’s equation, the osmolar scale is more generally used in physiological studies. As we shall see, van’t Hoff’s law is a limiting law that is true only for dilute solutions. In this limit of dilute solutions, both osmolal and osmolar concentration scales converge to the same results.

To illustrate the magnitude of osmotic pressure, ideal solutions of 10 mM glucose or 5 mM NaCl, which dissociates into two particles, both have an osmolarity of 10 mosmol L−1 and an osmotic pressure at 37°C of 0.082 L·atm·moL−1·K−1 × 310 K × 0.01 mol·L−1 = 0.254 atm or 193 mmHg. Thus, the osmotic pressure of even dilute solutions are large in comparison to normal hydrostatic pressures in physiological systems.

IIIC Thermodynamic Derivation of van’t Hoff’s Law

One of the conclusions of chemistry is that all spontaneous processes are accompanied by a decrease in free energy. The total free energy of a solution can be divided among its components. This parceling out of the Gibbs free energy, G, is embodied in the concept of chemical potential:

(16.2)

(16.2)

where μi is the chemical potential of component i, ni is the number of moles of component i and i≠k. The chemical potential of a component of a solution consists of three terms: a standard potential, which refers to the chemical energy involved in the formation of the material from standard states; a compositional term, which depends on the presence of other constituents; and a work term, encompassing other work required (per mole) to bring additional material into the solution. The work term in the chemical potential of water is  where

where  is the volume of water per mole and P is the pressure. The electrochemical potential of ions in solution requires the inclusion of an electrical work term,

is the volume of water per mole and P is the pressure. The electrochemical potential of ions in solution requires the inclusion of an electrical work term,  where zi is the ion’s valence, F is Faraday’s constant, and ψ is voltage.

where zi is the ion’s valence, F is Faraday’s constant, and ψ is voltage.

In the case of a solution separated from pure water by an ideal semipermeable membrane, water movement will occur when there is a difference in the chemical potential of water on the two sides of the membrane, such that water movement will result in a decrease in free energy. When the pressure applied to the solution is equal to the osmotic pressure, equilibrium is established and the chemical potential of water is equal on both sides of the membrane; no net water movement occurs. This equality of chemical potential is written as:

(16.3)

(16.3)

where the subscripts L and R refer to the left and right sides of the semipermeable membrane, μ0 is the chemical potential of liquid water in its standard state (pure water at 1 atm pressure) and aw is the activity of water. For an ideal solution, the activity of water can be replaced by its mole fraction, Xw

(16.4)

(16.4)

where nw and ns are the moles of water and solute, respectively. The balance of the chemical potential can be written as:

(16.5)

(16.5)

Consider the situation in Fig. 16.3, where pure water is on the right side of the membrane and a solution is on the left. Xw,R = 1.0 and thus, ln Xw,R = 0. Rearranging we find:

(16.6)

(16.6)

The mole fractions of water and solute in a solution must sum to 1.0. This is expressed as:

(16.7)

(16.7)

where Xs,L is the mole fraction of solute in the solution on the left. In dilute solutions, Xs,L<<1.0, and thus, ln (1− XS,L) ≈ −XS,L. Substitution of this approximation in Equation 16.6 gives:

(16.8)

(16.8)

The left-hand side of Equation 16.8 is just the osmotic pressure, π, which is equal to the extra pressure that must be applied to the solution on the left side in order to establish equality of the chemical potential of water on the two sides of the membrane. For physiological studies, it is convenient to express π in terms of concentration. From the definition of mole fraction and the assumption of dilute solutions (ns<<nw), we get:

(16.9)

(16.9)

where  is the total volume of solution and Cs is the concentration of impermeable solute on the solution side of the membrane. This last expression is the van’t Hoff equation for the osmotic pressure, Equation 16.1. The thermodynamic derivation entails two assumptions: (1) the solution is sufficiently dilute as to approach ideality; and (2) the solution is incompressible so that

is the total volume of solution and Cs is the concentration of impermeable solute on the solution side of the membrane. This last expression is the van’t Hoff equation for the osmotic pressure, Equation 16.1. The thermodynamic derivation entails two assumptions: (1) the solution is sufficiently dilute as to approach ideality; and (2) the solution is incompressible so that  It is important to recognize that Equation 16.9 is not exact for physiological solutions. Rather, it is an approximation that is strictly true only for dilute ideal solutions.

It is important to recognize that Equation 16.9 is not exact for physiological solutions. Rather, it is an approximation that is strictly true only for dilute ideal solutions.

The van’t Hoff equation is based on thermodynamics and, as such, it tells us nothing about the rate of osmosis or the mechanism by which it occurs. Conceivably, the semipermeable membrane could be like a sieve that allows water to pass freely while blocking solute movement. Alternatively, solvent could dissolve in the membrane, whereas solute is insoluble. Both of these models would exhibit osmotic flow from the region of low osmotic pressure (pure water) to that of high osmotic pressure (impermeant solute solution). The mechanism by which osmosis occurs must be determined by methods of chemical kinetics, and must be determined for every membrane-solvent pair.

IIID Other Colligative Properties of Solutions

The thermodynamic derivation given previously indicates that osmotic pressure (and osmotic flow) originates in the lowering of the chemical potential of water by the amount ≈RTXs when solute is dissolved. Several other properties of solutions also are a consequence of the lowered chemical potential of water because of dissolution of solutes. Together, these are called the colligative properties (from the Latin, ligare, meaning to bind) and include osmotic pressure, vapor pressure depression, boiling point elevation and freezing point depression. Consider two open compartments enclosed in a chamber. One compartment contains pure water and the other a solution of a non-volatile solute. The vapor pressure above a solution is defined as the partial pressure of water vapor in equilibrium with the solution. Since the vapor pressure of pure water is higher than that of the solution, water vapor above pure water will be at a higher pressure than that above the solution. As a result, water vapor will diffuse from the water side to the solution side. At the surface of the solution, water vapor will condense because the vapor pressure there will be higher than the equilibrium vapor pressure for the solution. Thus, water will move from the pure water to the solution side. In short, “osmosis” would occur through the “semipermeable membrane” represented by the surfaces of the two fluids and the intervening air. This illustrates the strong connection among the colligative properties of solutions. Laboratory osmometers typically use either vapor pressure depression or freezing point depression to determine the total solute concentration in an aqueous solution.

IIIE Osmotic Pressure of Non-ideal Solutions

As discussed above, the van’t Hoff equation is an approximation that adequately describes the osmotic pressure for dilute solutions. Its derivation requires the assumptions that the solutions are dilute and that the solutions are ideal. Here, ideal means that Raoult’s law (vapor pressure is proportional to mole fraction of solvent) is valid for the solution (Hildebrand, 1955; Kiil, 1989). Because the behavior of real solutions is not ideal, the van’t Hoff equation must be modified to include a correction term, the osmotic coefficient (ϕs):

(16.10)

(16.10)

At physiological concentrations, the osmotic coefficients for NaCl and CaCl2 are 0.93 and 0.85, respectively. This means the osmolarity of 150 mM NaCl is 0.93 × 2 × 150 = 279 mosmol L−1 and the osmolarity of 150 mM CaCl2 is 0.85 × 3 × 150 = 382.5 mosmol L−1. The osmotic coefficients for electrolytes vary with temperature, concentration and the chemical nature of the electrolyte. For most electrolytes, ϕ<1.0 for dilute solutions, due to weak attraction of the ions. At higher concentrations, ϕ increases to exceed 1.0. Values for the osmotic coefficients for electrolytes can be found in Robinson and Stokes (1959) or can be calculated from the parameters tabulated by Pitzer and Mayorga (1973). These osmotic coefficients are corrections to van’t Hoff’s law due to interactions only for the particular solute. When more than one solute is present, interactions could occur that are not accounted for by the osmotic coefficients. Therefore, calculations of the osmotic pressure of a mixture of solutes, even when osmotic coefficients are used, are only approximations.

Non-electrolytes and polyelectrolytes, especially proteins, also show marked departure from van’t Hoff’s law with increasing concentration. According to Equation 16.10, the osmotic coefficient for a single solute can be calculated as:

(16.11)

(16.11)

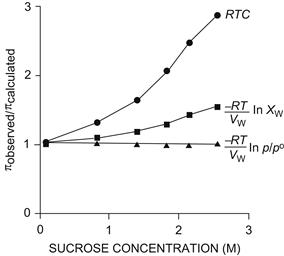

The osmotic coefficient for sucrose is plotted against sucrose concentration in Fig. 16.4. The osmotic coefficient is nearly 1.0 in dilute solutions, but approaches 3 in saturated sucrose solutions. Thus, the van’t Hoff equation successfully describes the osmotic pressure of dilute solutions, but fails at high solute concentrations. The failure of the van’t Hoff equation for highly concentrated solutions is due to deviation of reality from the assumptions used to derive the equation, that solutions are dilute and ideal. The osmotic coefficient accounts for these deviations.

FIGURE 16.4 Osmotic coefficients as a function of sucrose concentration. Plotted are the molar osmotic coefficient, defined as ϕs in Equation 16.11 (•), obtained by dividing the observed osmotic pressure by RTC; the rational osmotic coefficient, g, defined in Equation 16.15 ( ), obtained by dividing the observed osmotic pressure by

), obtained by dividing the observed osmotic pressure by  ln Xw; and the observed osmotic pressure divided by that predicted by vapor pressure measurements

ln Xw; and the observed osmotic pressure divided by that predicted by vapor pressure measurements  ln p/p0 according to Equation 16.13 (

ln p/p0 according to Equation 16.13 ( ). Deviation of the molar osmotic coefficient from 1.0 means that the van’t Hoff law fails to describe adequately the osmotic pressure at high concentrations, but is accurate for dilute solutions. The van’t Hoff law requires the assumption of dilute solution and ideal behavior. Deviation of the rational osmotic coefficient from 1.0 means that the solution is not ideal, as the equation requires this assumption. The nearly perfect agreement between the theoretical osmotic pressure predicted from vapor pressure measurements illustrates the connection between these two colligative properties. Data from Glasstone (1946).

). Deviation of the molar osmotic coefficient from 1.0 means that the van’t Hoff law fails to describe adequately the osmotic pressure at high concentrations, but is accurate for dilute solutions. The van’t Hoff law requires the assumption of dilute solution and ideal behavior. Deviation of the rational osmotic coefficient from 1.0 means that the solution is not ideal, as the equation requires this assumption. The nearly perfect agreement between the theoretical osmotic pressure predicted from vapor pressure measurements illustrates the connection between these two colligative properties. Data from Glasstone (1946).

For high solute concentrations, we can calculate the osmotic pressure from the mole fraction of water without assuming a dilute solution by identifying π = PL−PR in Equation 16.6:

(16.12)

(16.12)

This equation still requires the assumption of ideal solution behavior: the activity of water is equal to its mole fraction. The expression for osmotic pressure without assuming a dilute solution or ideality is given by:

(16.13)

(16.13)

where p and p0 are the vapor pressures of the solution and pure water, respectively.

The rational osmotic coefficient, g, accounts for non-ideal behavior and is defined as:

(16.14)

(16.14)

Then, from Equations 16.12–16.14, we find that:

(16.15)

(16.15)

The rational osmotic coefficient is closer to 1.0, but still deviates significantly at higher sucrose concentrations where solution behavior is further from ideal (see Fig. 16.4). In contrast, the ratio of the observed osmotic pressure to the theoretical osmotic pressure calculated from vapor pressure measurements, according to Equation 16.13, is very close to 1.0 throughout the entire concentration range. This shows the validity of Equation 16.13 and the absolute correlation between vapor pressure depression and osmotic pressure as different measures of the same phenomenon, the lowering of the activity of solvent water by the dissolution of solute. Equation 16.12 does not adequately describe the variation of π with Cs because it requires ideal adherence to Raoult’s law (vapor pressure is proportional to Xw); van’t Hoff’s limiting law further deviates from a linear relationship between π and Cs because it requires the additional approximation of dilute solutions. Despite these limitations in the high concentration domain, van’t Hoff’s law remains a good approximation for electrolyte solutions in the physiological range.

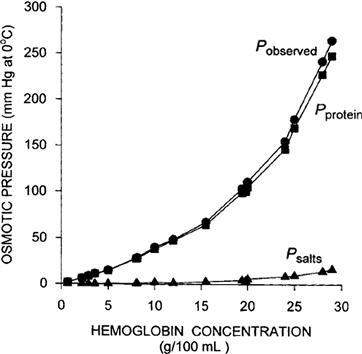

Because of their importance in physiological systems, the non-ideality of the osmotic pressure of protein solutions requires special comment. Adair (1928) found that the observed osmotic pressure increased faster than the concentration in hemoglobin solutions, as shown in Fig. 16.5. Part of the osmotic pressure was due to the unequal distribution of ions across the semipermeable membrane caused by electric charge on the immobile protein molecules. This is the Gibbs–Donnan equilibrium, discussed in more depth later. The contribution of the Gibbs–Donnan distribution to osmotic pressure is small, however, and nearly all of the non-linearity between π and Cs is due to the protein itself. From the data obtained by Adair (1928), ϕHb = 4.03 at the concentration of hemoglobin within erythrocytes (34.4 g hemoglobin per 100 ml of solution).

FIGURE 16.5 Dependence of the observed osmotic pressure on hemoglobin concentrations. Pobserved is the observed osmotic pressure (•). Psalts is the contribution of the salts to the osmotic pressure as calculated from the Gibbs–Donnan distribution and the van’t Hoff equation ( ). Protein is the contribution of the protein itself to the observed osmotic pressure, calculated as Pobserved−Psalts (

). Protein is the contribution of the protein itself to the observed osmotic pressure, calculated as Pobserved−Psalts ( ). Data from Adair (1928).

). Data from Adair (1928).

The observed osmotic pressure of solutions of plasma proteins also increases more rapidly than concentration, but the degree of deviation from linearity is different for different proteins. Thus, serum albumin shows marked deviation, whereas γ-globulins are more nearly linear. The empirical fits to the concentration-dependence of osmotic pressure are given by Landis and Pappenheimer (1963) as:

(16.16)

(16.16)

In each of these three equations, the first term represents the limiting law of van’t Hoff.

The rather large ϕs for proteins and polymers is due in part to excluded volume effects. That is, proteins and polymers exclude solvent from a larger volume than inorganic ions. The lowering of the free energy of solvent water upon dissolution of solute, which gives rise to osmosis, can be calculated from the increase of entropy on mixing. This entropy of mixing depends on the volume occupied by the solute. From considerations of the excluded volume, it can be shown (Tanford, 1961) that the expected osmotic pressure is given as:

(16.17)

(16.17)

IIIF Equivalence of Osmotic and Hydrostatic Pressure

As mentioned earlier, Pfeffer originally observed a linear relationship between the flow rate and the concentration of solute. This is expressed as:

(16.18)

(16.18)

where Jv is the volume flux in cm3·s−1 per unit area of membrane, Lp is variously called the filtration coefficient, hydraulic conductivity, or hydraulic permeability and Δπ is the osmotic pressure difference. A positive Jv in Equation 16.18 represents flux from the left to the right compartment and this is the order in which the osmotic pressure difference is taken. The minus sign before Lp indicates flux is from the region of low osmotic pressure to the region of high osmotic pressure. In Fig. 16.3A, πL>πR, Δπ>0, and Jv is negative. This means that the flux is from the right to the left compartment. The flow across an extent of membrane is just the flux times the area exposed to the driving forces, expressed as:

(16.19)

(16.19)

where A is the area of the membrane and Qv is the flow in units of cm3·s−1.

In the absence of solute, the volume flow across Pfeffer’s artificial membrane was also linearly related to the hydrostatic pressure:

(16.20)

(16.20)

In a study on collodion membranes, Meschia and Setnikar (1958) found that the proportionality constant for hydrostatic pressure-driven filtration was the same as the constant relating flow and osmotic pressure. That means that the Lp in Equation 16.19 is the same as the Lp in Equation 16.20. Thus, not only can the osmotic flow be nulled by opposing osmotic pressure with an equal but opposite hydrostatic pressure, but the equivalent proportionality implies that the mechanism of volume flow is also identical for osmotic and hydraulic flow. The equivalence of osmotic and hydrostatic pressures allows us to write:

(16.21)

(16.21)

This equation describes the net flow that would be observed in the presence of both hydrostatic and osmotic pressure differences across a semipermeable membrane.

IIIG Reflection Coefficient

Equation 16.1, van’t Hoff’s law, describes the relation between osmotic pressure and concentration when a solution is separated from water by an ideal semipermeable membrane. Recall that a semipermeable membrane is defined as absolutely impermeable to the solute. Real membranes may not fit this ideal; they may be somewhat permeable to the solute. When membranes are permeable to the solute, the measured osmotic pressure is actually less than that predicted by van’t Hoff s law. This phenomenon has led to a second membrane parameter, σ, the reflection coefficient which is defined as:

(16.22)

(16.22)

The reflection coefficient derives its name from the idea that all of the collisions of solute with a semipermeable membrane will result in the solute being reflected back into the solution. The reflection coefficient for an ideal membrane is 1.0. For a permeable solute, some fraction of the collisions with the membrane will result in permeation of the membrane, so that σ<1.0 and the observed osmotic pressure will be less than that predicted by van’t Hoff s law. The value of σ is not simply the fraction of collisions that penetrate the membrane. It involves discrimination by the membrane between solvent and solute. Thus, σ is a parameter that is different for every membrane-solute pair. A vapor pressure osmometer or a freezing-point osmometer would still register the proper osmolarity of the solution, however (for non-volatile solutes). A molecular interpretation of the origin of the reflection coefficient is given later.

Permeation of the solute should reduce osmotic flow along with osmotic pressure. In the presence of both hydrostatic pressure differences and concentration differences across a membrane, the resulting volume flow is given by:

(16.23)

(16.23)

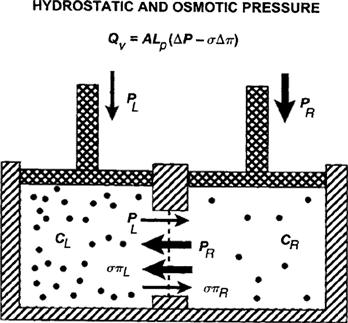

where σi is the reflection coefficient of solute i, and πi,L and πi,R are the osmotic pressures of solute i on the left and right sides of the membrane, respectively. The πi in this equation is that given by van’t Hoff’s law; its multiplication by the reflection coefficient, σ, gives the effective osmotic pressure. The consequence of a combination of hydrostatic and osmotic pressures on the flow across a membrane is shown in Fig. 16.6.

FIGURE 16.6 Net flow in the presence of osmotic and hydrostatic pressures. For a real membrane, the effective osmotic pressure on the left, σπL, causes flow toward the left, while the applied hydrostatic pressure, PL, drives flow to the right. A similar situation occurs on the right. The net flow is driven by the balance of the forces, ΔP−σΔπ, and is proportional to the area, A, and the hydraulic conductivity, Lp.

IV Mechanisms of Osmosis

The ultimate cause of osmosis is the reduction of the chemical potential of water in a solution. This thermodynamic statement and equations derived from it tell us nothing about the rate of osmosis or its mechanism. Several possible mechanisms have been investigated. As will be developed, classes of models can be distinguished by comparing the proportionality between applied force, which is either a pressure or concentration gradient, and water flow.

IVA Microporous Membranes

IVA1 Osmotic and Pressure-Driven Flow through Porous Membranes

The equivalence of Lp for osmotic and pressure-driven flow suggests a common mechanism. At least three different models have been proposed to explain flow across membranes: (1) hydrodynamic flow through a porous membrane; (2) diffusion through the membrane; and (3) non-hydrodynamic flow through narrow pores. As we shall see, it is likely that biological membranes are not modeled well by any one of these. Despite this, we shall consider these model membranes because investigators have relied heavily on them to clarify their thinking.

First, we consider a porous membrane as a model for understanding osmotic and hydrostatic pressure-driven flow and derive Lp, the proportionality constant relating pressure and flow. We assume the membrane is a flat, thin sheet of thickness δ. We imagine that the membrane is pierced by right-cylindrical pores of radius r, and the number of pores, N, per unit area is n = N/A. The membrane separates two compartments of water that are at different hydrostatic pressures. If we assume that the pores are large enough for laminar flow to occur, then the filtration flow will be given by the Poiseuille equation:

(16.24)

(16.24)

where qv is the flow per pore in cm3·s−1, η is the viscosity of the fluid, δ is the thickness of the membrane (equal to the length of the pore), and ΔP is the pressure difference across the pore. The π in this equation is the geometric ratio, 3.14…, and should not be confused with the symbol for osmotic pressure. Since the flow through N pores is just Nqv, the observed macroscopic flux and flow are:

(16.25)

(16.25)

Recall here that Jv is the flux, or flow per unit area of membrane and Qv is the flow in units of volume per unit time.

Equation 16.25 describes the steady-state flow of water across the membrane. Because at steady-state there is no buildup or depletion of water, there is no difference in the flow of water at any two points in the pore. Consequently, pressure changes linearly with distance through the pore, and the gradient of pressure, ΔP/δ, is constant.

A comparison of Equation 16.25 with Equation 16.20 indicates that the hydraulic conductivity is:

(16.26)

(16.26)

Thus, Lp is a parameter determined by the viscosity of the fluid and by membrane characteristics including the number of pores per unit area, n, the pore radius, and the membrane thickness.

IVA2 Diffusional Permeability of Porous Membranes: Pd

In the absence of a pressure gradient, solute and water cross a porous membrane by diffusion through the pores. If we assume that the membrane is impermeable at all other points, the permeability is given by Fick’s first and second law of diffusion:

(16.27)

(16.27)

where js is the flux of solute through one pore. The second expression describes the time dependence of the concentration profile over distance, x, within the pore. At steady-state, the concentration profile no longer changes. This means that  the concentration gradient is linear; and δC/δx = (CL−CR)/(0−δ) = −ΔC/δ, where δ is the thickness of the membrane. Total solute flux across the entire membrane, Js, is:

the concentration gradient is linear; and δC/δx = (CL−CR)/(0−δ) = −ΔC/δ, where δ is the thickness of the membrane. Total solute flux across the entire membrane, Js, is:

(16.28)

(16.28)

where n is the number of pores per unit area of membrane. According to this equation, the observed macroscopic flux of solute across a porous membrane is linearly related to the concentration difference by a coefficient that includes properties of the solute (diffusion coefficient) and the membrane (thickness, pore density and pore cross-sectional area). The permeability of the membrane to solute, ps, includes several parameters in Equation 16.28 that are difficult to obtain experimentally; ps relates solute flux, Js, to the difference in concentration across the membrane:

(16.29)

(16.29)

From Equations 16.28 and 16.29, ps is defined as:

(16.30)

(16.30)

Isotopic water on one side of a porous membrane is distinguishable from ordinary water and may be viewed as a solute. Thus, water itself will obey these equations. This allows us to define the diffusional permeability of water, Pd, for a porous membrane:

(16.31)

(16.31)

where Dw is the diffusion coefficient of water. The units of Pd are cm·s−1. Note that multiplication of a permeability by a concentration, as in Equation 16.29, gives a flux with units of mol·cm−2 s−1.

IVA3 Evidence for Pores: Pf/Pd Ratio

In the absence of a concentration gradient, pressure-driven water flow gives rise to a second permeability constant termed the filtration permeability or osmotic permeability, Pf, which has units of cm·s−1. Mauro (1957) realized that the proportionality constants relating pressure and concentration-gradient-driven water flow, Pf and Pd, provide evidence for the mechanism of transport. The ratio Pf/Pd should be 1.0 if water crosses by a dissolution-diffusion process. Mauro (1957) recognized that the flux of water in response to a pressure gradient could be partitioned into two components, diffusional and non-diffusional (e.g. bulk flow) and that the diffusional component of water flux, Jw, would obey the Nernst–Planck equation:

(16.32)

(16.32)

where Cw is the concentration of water. In the case where only a hydrostatic pressure is applied,  and

and  . Assuming steady-state flows and a uniform membrane, dP/dx = −ΔP/δ, and Equation 16.32 becomes:

. Assuming steady-state flows and a uniform membrane, dP/dx = −ΔP/δ, and Equation 16.32 becomes:

(16.33)

(16.33)

This flow of water is in units of moles of water per second per cm2 of membrane. It can be converted to units of volume per second per cm2 (the units of Jv) by multiplying by the volume of water per mole, or  :

:

(16.34)

(16.34)

This equation relates the volume flux to the pressure difference across the membrane.

The total volume flux was earlier given as Jv = LpΔP (see Equation 16.20). If diffusional flux is the only component of volume flux, Equations 16.20 and 16.34 may be combined to give:

(16.35)

(16.35)

Part of this expression for Lp incorporates Pd. Insertion of Equation 16.31 into Equation 16.35 gives:

(16.36)

(16.36)

This definition of Pf converts Lp into a parameter having the same units as Pd, thereby allowing direct comparison of filtration and diffusional permeabilities. The equality of Pf and Pd obtained in Equation 16.36 is dependent on the condition that the flow of water in response to a hydrostatic pressure difference is due only to diffusional processes. Thus, for a purely diffusional process, Pf/Pd = 1. In contrast, Mauro (1957) found that Pf/Pd was 727 in collodion membranes. That is to say, pressure-driven water movement was much greater than expected from a diffusional process. From this he concluded that pressure-driven and osmotic flow across these membranes was predominately non-diffusional.

IVA4 Physical Origin of Osmotic Pressure

If a porous membrane separates a solution containing only impermeant solutes from pure water, we observe experimentally that water flows through the membrane from the pure water to the solution side. The flow is proportional to the osmotic pressure of the solution times Lp (see Equation 16.20). The question is, what causes this water movement? Because the membrane is impermeable to solute, solute cannot enter the pores and the fluid in the pore is pure water. Consider a water molecule in the middle of the pore. How does the water “know” to move toward the solution side? It appears there are only two possible answers to this question. Either there is a concentration gradient of water within the pore, or there is a pressure gradient within the pore. These two possibilities are not mutually exclusive, but diffusion-driven water flow and pressure-driven water flow are often thought of as separate mechanisms. The dichotomy reflects the notion that water is an incompressible fluid. Water is not absolutely incompressible, however. The coefficient of compressibility is given as:

(16.37)

(16.37)

and the value of β for water is 4.53×10−5 atm−1. The equation for the volume of water is:

(16.38)

(16.38)

where V0 is the volume at a standard temperature and pressure (1 atm), and P is the pressure in excess of 1 atm. The coefficient of compressibility is virtually constant in the range −500 to +1000 atm. Equation 16.38 indicates that application of a negative pressure of 2.5 atm would expand a pure water solution by 0.01%, which corresponds to a change in the concentration of water of about 5 mM. Looked at the other way, an expansion of water of only 0.01% would induce a negative pressure of 2.5 atm, equal to the osmotic pressure of a 0.1 molal solution at 37°C.

Dainty (1965) proposed a model in which he considered the density of water immediately within the pore opening on the solution side. As solute molecules cannot enter the pore, Dainty reasoned that the concentration of water within the pore must be higher than in the solution. Because of this difference in concentration, he argued that water would diffuse into the solution side faster than water could diffuse into the pore. The resulting net movement of water toward the solution side would lower the density of water in the pore, thereby creating a reduced pressure. Bulk movement of water down its pressure gradient would follow.

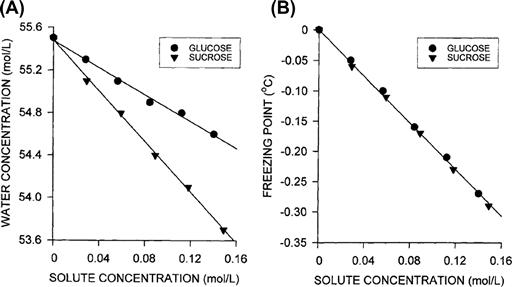

This explanation of the origin of osmotic pressure supposes that the driving force is actually water diffusing down its concentration gradient. The data in Fig. 16.7 show, however, that the concentration of water cannot be the major determinant of the colligative properties of solutions. In Fig. 16.7A, the water concentration in solutions of sucrose and glucose are plotted against the concentration of the solute. The water concentration is indeed decreased by dissolving solute, but sucrose, being almost twice as large as glucose, displaces almost twice as much solvent. As shown in Fig. 16.7B, however, the colligative properties, represented here by the freezing point depression, depend only on the concentration of solute. Solutions with equal solute concentrations but different water concentrations have the same freezing point.

FIGURE 16.7 Effect of solute concentration on water concentration and freezing point depression in glucose and sucrose solutions. (A) Because solute displaces water, the water concentration decreases with increasing solute concentration. Sucrose is nearly twice the size of glucose. Consequently, there is less water in a sucrose solution having the same molarity as a glucose solution. (B) The freezing point depression, however, is dependent only on the solute concentration. It is the mole fraction of water that determines the colligative properties of solutions (the osmotic pressure, vapor pressure depression, boiling point elevation, and freezing point depression). (Data from The Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, Chemical Rubber Company, Cleveland, OH, 1965.)

An alternative view of the physical origin of the osmotic pressure begins with the notion of pressure as a force divided by an area. The macroscopic concept of pressure relies on the averaging over time of the myriad of collisions that produce the pressure. By Newton’s law, force is the time derivative of momentum. An elastic collision of a solvent or solute molecule with the walls of the vessel results in a momentum change of 2mv, where m is the mass of the molecule and v is its velocity, which contributes to the pressure against the vessel wall. At the entrance to the pore, however, solute molecules cannot transfer their momentum to the interior of the pore because they collide with the rim of the pore and are reflected back into the solution. Thus, the water molecules immediately inside the pore experience a momentum deficit that is equal to the component of pressure contributed by the solute molecules in the bulk phase.

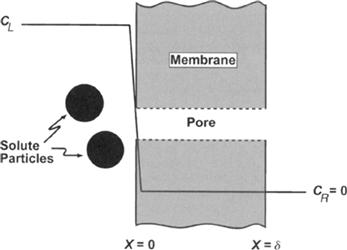

Figure 16.8 shows the one-dimensional concentration profile of solute molecules near a pore opening. Because there is a steep solute gradient, there should be a diffusion of solute toward the pore opening. However, the actual steady-state flux of solute in this direction is zero because of the force exerted on the solute molecules by the membrane. The equation that describes the solute flux, Js, in units of mol cm−2s−1, is:

(16.39)

(16.39)

where C(x) is the concentration of solute at position x, D is the solute diffusion coefficient in units of cm2·s−1, f is the force per solute molecule and R and T have their usual meanings.

FIGURE 16.8 Concentration profile in the vicinity of a pore in a microporous membrane. The membrane is impermeable at all places except the pores, where water may penetrate but solute particles (solid circles) are too large to enter the pore. The concentration of solute in the bulk solution (CL) must fall to zero upon entering the pore. The steep concentration gradient is accompanied by diffusion towards the pore that is balanced by reflection of solute by collision with the membrane.

Villars and Benedek (1974) derived an equation for the drop in pressure immediately inside the pore on the solution side by setting the flux in Equation 16.39 to zero and analyzing the net force on a plug of volume near the pore. Under steady-state conditions with zero Js through the pore, Equation 16.39 gives:

(16.40)

(16.40)

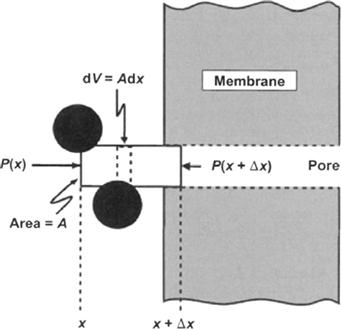

where f C(x) is the force per molecule times the number of molecules per unit volume, or the force per unit volume. Figure 16.9 shows a volume element near the opening of the pore on the solution side. We consider the forces acting on the element of fluid with an area A from a point x well within the bulk solution to a point x + Δx just inside the pore. We assume that this element is in mechanical equilibrium; although it may be moving, it is not accelerated or decelerated. The forces acting on the volume are contact forces on the edges of the volume and additional forces acting on the solute molecules alone to counteract the diffusive flux. At mechanical equilibrium the sum of the forces must be zero. This is written as:

(16.41)

(16.41)

where Fs is the total force acting on the solutes in the volume and Fc is the net contact force due to the pressure from the adjacent volume elements. The net contact forces are the result of pressure acting over an area:

(16.42)

(16.42)

The forces acting on the volume due to the solute particles is given by integrating Equation 16.40:

(16.43)

(16.43)

Inserting the volume element dV = A dx and fC(x) = RT∂C(x)/∂x from Equation 16.40, we obtain:

(16.44)

(16.44)

Since C(x + Δx) = 0 because solute particles are not in the pore, this becomes:

(16.45)

(16.45)

where the negative sign indicates that Fs is directed to the left. Inserting Equations 16.42 and 16.45 into Equation 16.41, we have:

(16.46)

(16.46)

or

(16.47)

(16.47)

This last equation indicates that the pressure experienced by the volume of fluid immediately inside the pore is less than the bulk pressure, P(x), by the amount RTCL, where CL is the concentration of impermeant solute in the solution on the left of the membrane. This analysis is consistent with the intuitive idea that water movement from the water side to the solution side of a semipermeable membrane must be due to a real force, which appears in this analysis to be due to the momentum deficit, and thus pressure deficit, within the pore on the solution side.

FIGURE 16.9 Forces acting on a volume element immediately adjacent to a pore opening. The ideal, porous, semipermeable membrane separates pure water on the right from solution of impermeant solute on the left. The volume element has an area, A, equal to the cross-sectional area of the pore. The pressure in the bulk phase at position x is P(x). The pressure at position x + Δx, just within the pore, is P(x + Δx). The net force on the element is the sum of the forces at both ends plus the forces acting only on the solute particles (solid circles) within the element.

IVA5 Physical Interpretation of the Reflection Coefficient, σ

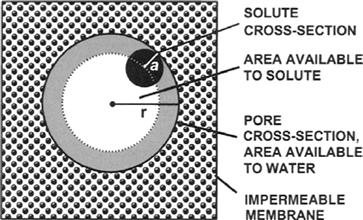

The microporous semipermeable membrane presented previously distinguishes between solvent water and solute on the basis of pore and solute size. That is, the solute is too large to enter the pore and so cannot cross the membrane. If the pores were somewhat larger or the solute molecules smaller, the solute could enter the pore, but with a lower probability than water because of the tight fit. In this case, rather than the solute being absolutely impermeant, the membrane would allow its slow passage. How does this affect the situation? Let us suppose that solute molecules that hit the rim of the pore before entry are reflected back into the bulk solution. This is shown diagrammatically in Fig. 16.10, looking down the axis of the pore perpendicular to the surface of the membrane. The area of the pore that is accessible to solute is:

(16.48)

(16.48)

where a is the radius of the solute molecule. Assuming that the radius of water molecules (0.75 Å) is negligible compared to the pore’s radius, the ratio of areas available to solute and solvent water is:

(16.49)

(16.49)

The fraction of collisions of solute molecules with the pore opening that are reflected back, compared with those of water, is approximated by the ratio of the area of the gray annulus in Fig. 16.10 to the cross-sectional area of the pore. This is identified with the reflection coefficient:

(16.50)

(16.50)

According to this view, the concentration of solute immediately within the pore would not be zero, as in the case when the solute was impermeant, but instead would be (1−σ)C and the excluded concentration would be σC. Thus, the momentum deficit inside the pore would be due only to the excluded solute and would be equal to σRTC, which is equal to σπ.

FIGURE 16.10 A physical interpretation of the reflection coefficient, σ, for a solute and a porous membrane. The view is down the pore in a direction perpendicular to the membrane. The pore is modeled as a right circular cylinder of radius r. The model assumes that any contact of the membrane with a solute particle of radius a (solid circle) will result in reflection of the particle back into the solution. The area available to solute is indicated in white. The total area of the pore, white plus gray annulus, is available for water movement.

In addition to entrance effects, the concentration profile within the pore will be influenced by the combination of diffusion through the pore, solvent drag due to movement of fluid in response to pressure gradients and interaction of the solutes with the non-linear velocity profile within the pore. Laminar flow through long pores is characterized by a parabolic velocity profile, with a motionless layer of fluid adjacent to the pore walls and most rapid flow in the center. Large solute molecules will span several layers of velocity, thereby distorting the velocity profile and changing the solute molecule’s velocity. Various equations have been derived to relax the assumption of negligible water radius and to relate the effective filtration area of the solute to the geometric radius of the pore (Renkin, 1954; Villars and Benedek, 1974; Hobbie, 1978). Although models assuming hydrodynamic flow through pores have been useful, their applicability to osmotic flow across biological membranes remains an open question.

IVB Lipid Bilayer Membranes: the Dissolution–Diffusion Model

There are two types of lipid bilayer membranes that are useful models of membranes: the lipid vesicle and the planar bilayer membrane. The lipid vesicle is a small spherical shell of lipid usually produced by sonicating a dispersion of lipid in water. Planar bilayer membranes consist of a thin film of phospholipids formed over a small hole in a partition between two aqueous compartments. The film is formed by “painting” the hole with a non-polar solvent containing the lipids, which then spontaneously form a bilayer to separate fully the two solutions. This arrangement allows measurement of electrical and permeability properties of the bilayer. In the case of the liposome, the inner compartment is exceedingly small and experimentally inaccessible. In both cases, there are no components of the membranes other than the lipid.

IVB1 Osmotic and Pressure-Driven Flow for the Dissolution-Diffusion Model: Pf

One model of water permeation through the lipid bilayer supposes that the water dissolves in the lipid phase and crosses the membrane by simple diffusion. In this model, the solution in contact with the membrane is one phase, while the hydrophobic core of the membrane is a second phase. Equilibrium of water in the solution phase with water in the membrane phase is described by equating the chemical potential of water in the two phases:

(16.51)

(16.51)

where Xw(solution) and Xw(membrane) are the mole fractions of water in the solution in equilibrium with the membrane and in the membrane phase, respectively. The partition coefficient is defined as:

(16.52)

(16.52)

Consider the case where only osmotic pressure drives water flow and hydrostatic pressure across the membrane, ΔP, is 0. Since water generally partitions poorly into hydrocarbon solvents, we may assume that the mole fraction of water in the membrane phase is low. That is, the water concentration is dilute, and we may replace the mole fraction of water with its concentration:

(16.53)

(16.53)

where  is the partial molar volume of lipid in the membrane. If the concentration of water immediately inside the membrane is in equilibrium with the solution in contact with the membrane, we combine Equations 16.52 and 16.53 to get:

is the partial molar volume of lipid in the membrane. If the concentration of water immediately inside the membrane is in equilibrium with the solution in contact with the membrane, we combine Equations 16.52 and 16.53 to get:

(16.54)

(16.54)

For dilute solutions, this is approximated by:

(16.55)

(16.55)

where Cs is the solute concentration. The concentration of water immediately inside the left side of the membrane, Cw,L, is given by Equation 16.55 where Cs is the concentration of solute in the solution on the left side of the membrane. A similar expression pertains to the concentration of water immediately inside the membrane on the right side (Cw,R). From the concentrations of water at both faces of the membrane, its diffusion across the membrane is given by Fick’s law:

(16.56)

(16.56)

where  is the diffusion coefficient of water in the membrane phase. Substitution from Equation 16.55 into Equation 16.56 gives:

is the diffusion coefficient of water in the membrane phase. Substitution from Equation 16.55 into Equation 16.56 gives:

(16.57)

(16.57)

The flux of water, Jw, is in units of moles of water per second per cm2 of membrane. It is converted to units of volume flow by multiplying by Vw, as in Equation 16.34, to obtain:

(16.58)

(16.58)

The last term on the right is the osmotic pressure difference, Δπ. This equation relates the volume flux to the osmotic pressure difference when the mechanism of water flow is dissolution and diffusion. Comparison to the earlier description of osmotic flow by Equation 16.18 allows us to identify Lp as:

(16.59)

(16.59)

From the definition, Pf = LpRT/ we get the expression for Pf as:

we get the expression for Pf as:

(16.60)

(16.60)

Equation 16.58 was derived for an osmotic gradient (ΔCs>0) in the absence of a hydrostatic gradient (ΔP = 0). The expression relating volume flux and pressure when ΔCs = 0 can be derived by returning to Equation 16.51 and setting the mole fractions of water on the two sides of the membrane equal, while the pressures differ. The result is that exactly the same Lp is derived for pressure-driven flow as for osmotic flow when the mechanism is by rapid dissolution of water followed by slow diffusion through the lipid membrane phase (Finkelstein, 1987).

IVB2 Diffusional Water Permeability through Lipid Membranes: Pd

The permeability of lipid membranes to a diffusional water flux is expressed as:

(16.61)

(16.61)

where Pd is the diffusional permeability and ΔCw is the difference in water concentration across the membrane. The overall permeation of the membrane by water is a consequence of three steps: dissolution into the membrane phase at the left interface; diffusion across the membrane phase; and reversal of dissolution at the right interface. If we assume, as we did in the derivation of Pf, that the rate-limiting step is diffusion through the membrane phase, then Equation 16.61 may be written as:

(16.62)

(16.62)

From Equation 16.54, this is:

(16.63)

(16.63)

Because  , this becomes:

, this becomes:

(16.64)

(16.64)

Pd can be identified by comparing Equations 16.64 and 16.61:

(16.65)

(16.65)

IVB3 Pf/Pd Ratio for the Dissolution–Diffusion Model

The expressions for Pf in Equation 16.60 and Pd in Equation 16.65 derived for a lipid membrane under identical assumptions (equilibrium at the interfaces with relatively slow diffusion across the membrane), indicate that the Pf/Pd ratio for diffusive flow of water across lipid membranes should be 1.0. Cass and Finkelstein (1967) measured the osmotic and diffusive permeability of planar lipid bilayers and found that, within experimental uncertainty, the ratio was indeed 1.0. The uncertainty arose mainly in the determination of Pd because of the presence of unstirred layers adjacent to the planar lipid bilayer. These unstirred layers are an additional diffusional barrier that affects the experimental determination of Pd much more than Pf. In the flux equations, permeability appears as a conductance relating a flux (Jw or Js) to a driving force (ΔCw or ΔCs). Thus, the inverse of permeability is like a resistance. For a membrane in series with unstirred layers, the total resistance is the inverse of the observed permeability, which is the sum of the resistances offered by the individual barriers, the membrane and the unstirred layers. We write this as:

(16.66)

(16.66)

From this equation, it is plain that if Pu, the combined permeability of the unstirred layers on both sides of the membrane, is less than infinity, the observed Pd will be less than the actual Pd of the membrane alone. Since diffusion of water through the unstirred layer is given by Fick’s law, Equation 16.66 may be rewritten as:

(16.67)

(16.67)

where δL and δR are the equivalent unstirred layer thickness on the left and right sides of the membrane.

Unstirred layers also can affect measurement of the coefficients for pressure gradient-driven flow, Pf and Lp, but the error introduced is much less than for concentration gradient-driven flow, Pd (Barry and Diamond, 1984; Finkelstein, 1987), and was safely ignored in evaluating the Pf/Pd ratio (e.g. Cass and Finkelstein, 1967). The osmotic flow sweeps solute toward the membrane on the side with lower osmolarity and away from the membrane on the other side. As long as convection is faster than diffusion, this diminishes the transmembrane osmotic gradient, reducing Jv for the apparent Δπ and causing underestimation of Pf and Lp. The observed Pf, Pf(obs), is given as:

(16.68)

(16.68)

where Pf(membrane) is the true membrane parameter, δ is the unstirred layer thickness, Jv is the volume flux and Ds is the diffusion coefficient of the osmolyte. The error can be minimized by determining Pf with a small Δπ so that Jv is small. Because Pf and Lp are proportional (Equation 16.36), the errors are also proportional.

The value of Pd and Pf varies with the lipid composition of the membrane and ranges from 1×10−5 cm·s−1 to 5×10−3 cm·s−1 (Deamer and Bramhall, 1986). Cholesterol, which generally reduces the fluidity of lipid bilayers, reduces Pd and Pf progressively with increasing cholesterol content (Finkelstein and Cass, 1968). The unidirectional flux across a lipid membrane equals Pd×Cw. Using a typical Pd of 1×10−3 cm·s−1 and a C of 55 mol·L−1, the unidirectional flux across a membrane is 5.5×10−5 mol·cm−2·s−1. By comparison, the unidirectional flux of water across a distance δ = 5 nm (approximately the thickness of the lipid bilayer) can be calculated as (Dw×Cw)/δ. Using 3×10−5 cm2·s−1 for Dw, the unidirectional flux of water in water is 3.3 mol·cm−2·s−1. Thus, water flux through the membrane is about 60 000 times slower than that through water. Nevertheless, the water flux is still enormous. Taking 0.7 nm2 as the average area of a typical phospholipid in the bilayer, the unidirectional water flux corresponds to about 2.2×105 water molecules passing each phospholipid molecule each second.

IVC Flow through Narrow Pores: Pf/Pd Ratio

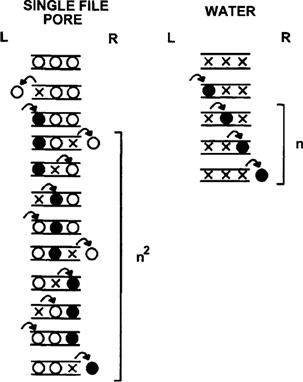

The equations derived earlier for Pf for a porous membrane required the assumption that the pores were large enough to allow laminar flow as described by the Poiseuille equation. Suppose that the pores are so narrow that water passes through the pores in single file. It is clear that laminar flow cannot occur here and the Poiseuille equation does not apply. As shown in Fig. 16.11, the narrow pore restricts free diffusion in the pore because diffusion of one water molecule from one position in the pore to the next requires its neighbor to move away to provide a vacancy. In this way, diffusion within the restricted geometry of the pore becomes a collective property of all of the molecules in the pore. The likelihood that a tracer molecule will diffuse all the way through the pore will depend on the number of water molecules in the pore, as movement of tracer water (solid circle) through the pore requires the movement of a vacancy (×) all the way through the pore.

FIGURE 16.11 Jumping model of diffusion of water through a narrow pore. In the model of free water diffusion (right), tracer water (solid circles) makes successive jumps from one vacancy (×) to another. In order to move three places, it must make three jumps. In a narrow pore (left), tracer water cannot move to the next position in the pore unless a vacancy is present because unlabeled water (open circles) cannot move out of the way. Movement of tracer water from one site to the next in the pore requires a vacancy to diffuse all the way through the pore. Since the vacancy requires three steps to diffuse through the pore, tracer water diffusion through three steps in a narrow pore requires nine jumps. The result is that single-file diffusion becomes a collective property of the single file and is slower than free water diffusion.

Suppose that there are N water molecules in a pore. We may assume that the length of the pore, δ, is proportional to N, and that the water molecules reside in more or less specific positions separated by δ/N. In the free diffusion of liquid water in the bulk solution, according to Fick’s first law of diffusion, the flux of water is proportional to 1/δ or 1/N. In the case of a single-file diffusion through a narrow pore, the diffusion of a vacancy through the water within the pore looks exactly like the diffusion of water through a series of vacancies in free diffusion. Thus, the flux of the vacancy also is proportional to 1/N. The movement of tracer from one position to the next in the pore requires the diffusion of a vacancy all the way through the pore, so that the flux of tracer one step is proportional to 1/N. In order to diffuse all the way through the pore, the tracer must make N such jumps. The unidirectional flux of tracer over N steps of equal flux is given by Stein (1976):

(16.69)

(16.69)

where J0→N is the unidirectional flux of tracer across N steps (all the way through the membrane) and Jij is the unidirectional flux of tracer over one step. Since Jij requires diffusion of a vacancy all the way through the pore, it is proportional to 1/N. The unidirectional diffusional flux of tracer through a single-file pore is thus proportional to 1/N2, rather than 1/N. Pressure-driven flow, on the other hand, remains inversely proportional to pore length. The theoretical analysis of both pressure-driven flow and diffusive flow through a single-file pore has led to the conclusion that the proportionality constants relating Pf to 1/N and Pd to 1/N2 are identical. The result, for a single-file pore, is:

(16.70)

(16.70)

where N is the number of water “binding sites” within the pore (Finkelstein, 1987). A more recent theoretical analysis suggests that this result is true near equilibrium, but the ratio of osmotic to diffusive permeability may exceed N for a membrane far from equilibrium (Hernandez and Fischbarg, 1992).

IVD Mechanism of Water Transport across Lipid Bilayer Membranes

The previous discussion suggests that water transport across lipid bilayer membranes occurs by rapid dissolution at the membrane interface followed by diffusion across a hydrocarbon-like interior. Three observations strongly support this mechanism: (1) the Pf/Pd ratio, after correction for unstirred layers, appears to be close to 1.0 (Cass and Finkelstein, 1967; Andreoli and Troutman, 1971); (2) insertion of pore-forming antibiotics such as nystatin, amphotericin B or gramicidin A increases the Pf/Pd ratio to small values of N (between 3 and 5) (Holz and Finkelstein, 1970; Rosenberg and Finkelstein, 1978); and (3) the activation energy for water transport, typically 10–20 kcal·moL−1, is larger than the activation energy for free water diffusion, ≈4 kcal·moL−1, which should apply if water moves through a pore (Solomon, 1972; Fettiplace and Haydon, 1980). However, experimental studies of water permeation across liposomes appear to give a different answer. The Pf of liposomes, measured by turbidimetric methods, is not affected by the chain length of the lipids or the degree of saturation (Carruthers and Melchior, 1983; Jansen and Blume, 1995), whereas water solubility in hydrocarbons is affected by chain length (Schatzberg, 1963). Further, the activation energy of Pf in liposomes is only 3.2 kcal·moL−1 (Carruthers and Melchior, 1983), similar to the activation energy for free water diffusion. The Pf of liposomes is discontinuous near phase transitions of the lipid and Pf/Pd ratios from 7 to 23 have been reported (Jansen and Blume, 1995). From these observations, it appears that liposomes do not behave as planar lipid bilayers, perhaps because of membrane defects induced by the marked curvature of the membrane in these small structures. The activation energy has been taken as diagnostic of whether water traverses the membrane through pores or by diffusion through the lipid itself (Finkelstein, 1987; Verkman, 1993). Low activation energies of water transport are associated with a high Pf or Lp in membranes containing water channels or pores, whereas high activation energies are associated with a low Pf or Lp, indicating diffusional water transport in membranes without pores or when pores are blocked by mercurials (Table 16.2).

TABLE 16.2. Hydraulic Conductivity and its Apparent Activation Energy

| Tissue | Lp 10−10 L·N−1·s−1 | Ea kcal·moL−1 |

| Water channels | ||

| RBC, human | 18.0 | 3.9 |

| RBC, beef | 18.2 | 4.0 |

| RBC, dog | 23.0 | 4.3 |

| Prox. tubule BLM-V, rabbit | 21.9 | 2.5 |

| Liposomes + AQP1 | 30.8 | 3.1 |

| Water channels + mercurials | ||

| RBC, human + PCMBS | 1.3 | 11.6 |

| Prox. tubule BLM-V, rabbit + Hg | 4.4 | 8.2 |

| Diffusional | ||

| RBC, chicken | 0.6 | 11.4 |

| Intestinal brush border, rat | 0.9 | 9.8 |

| Ventricle, rabbit | 1.2 | 10.5 |

| Liposomes | 1.9 | 16.0 |

| PC bilayer | 1.6 | 13.0 |

| PC/chol bilayer | 0.4 | 12.7 |

| Water self-diffusion | — | 4.2 |

Hydraulic conductivity, Lp, and activation energy, Ea, are characteristic of the mechanism of water transport. High Lp and low Ea are typical of membranes containing functioning water channels, whereas low Lp and high Ea indicate diffusional water transport. Note that 10−10 L·N−1·s−1 (SI units)=10−12·cm3·dyn−1·s−1 (cgs units). RBC, red blood cell; BLM-V, basolateral membrane vesicles; AQP1, aquaporin-1; PCMBS, p-chloromercuribenzene sulfonate; PC, phosphatidylcholine; chol, cholesterol. For references, see Suleymanian and Baumgarten (1996).

In the dissolution–diffusion mechanism, water encounters a minimum of three sequential barriers: dissolution on one side of the membrane; transport across the hydrocarbon-like interior; and then removal from the membrane on the opposite side. Assuming rapid equilibration at the interfacial regions is equivalent to assuming that the barriers there are insignificant compared to the barrier of diffusion, but there is no a priori reason to make this assumption. The alternate view proposes that the rate-limiting step is lateral movement of the phospholipid head groups that creates a transient defect required for penetration of water into the interfacial region of the membrane (Trauble, 1971; Haines, 1994). Water transport through the hydrophobic core requires vacancies within the bilayer that form when hydrocarbon chains make gauche-trans-gauche kinks caused by the rotation of carbon–carbon bonds in the hydrocarbon tails. Kinks in the hydrocarbon tails propagate rapidly down acyl chains and provide sufficient space for water. Experimental support for this model comes from studies showing addition of cardiolipin to phosphatidylcholine liposomes decreases Pf without changing bilayer fluidity by stabilizing head group interactions (Shibata et al., 1994). These two models make very different assumptions, and the detailed mechanism of water permeation through lipid bilayers remains uncertain.

V Water Movement Across Cell Membranes

In the prior sections, we considered osmotic- or pressure-driven flow and diffusive flow of water across membranes that were characterized as: (1) porous membranes with pores large enough to allow laminar flow; (2) lipid membranes with no pores, but allowing water permeation by a dissolution–diffusion mechanism; and (3) membranes containing narrow pores. We found expressions for the osmotic permeability, Pf, and the diffusive permeability,Pd, for each and found that the membranes could be distinguished in principle by the ratio Pf /Pd: large values of Pf/Pd indicate a porous membrane, Pf/Pd = 1 signifies a diffusive mechanism and small values of Pf /Pd>1 are characteristic of narrow pores. What are the permeabilities of real biological membranes, and what do these permeabilities tell us about the routes of water transport through membranes?

VA Rate of Water Exchange: Experimental Measure of Pd

Paganelli and Solomon (1957) measured the diffusional exchange of water across erythrocyte membranes by rapidly mixing a suspension of the cells with an isotonic buffer with added tracer 3H2O. The mixture was forced down a tube and samples of the extracellular water were obtained by filtration at various distances, corresponding to various times of exchange. Paganelli and Solomon found that the half-time for exchange of 3H2O was 4.2 ms at room temperature. This means that 90% of all of the water within an erythrocyte is exchanged with extracellular water every 14 ms. This is an extraordinarily rapid rate of exchange. Erythrocytes are sufficiently small that the presence of an unstirred layer within the cells does not appreciably affect the determination of Pd (i.e. (δL + δR)/Dw<<1/Pd; see Equation 16.67).

Diffusional exchange of water across erythrocyte membranes also can be measured by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Relaxation of the nuclear spin states of hydrogen is much slower inside a cell than outside when a relatively impermeant paramagnetic ion like Mn2+ is added to the extracellular solution. This allows calculation of Pd because the relaxation of the spin states is then effectively limited by permeation through the membrane. The values of Pd for the erythrocyte determined by isotopic or NMR methods cluster around 4×10−3 cm·s−1 (Solomon, 1989).

VB Rate of Osmotic Flow: Experimental Measure of Pf and Lp

According to Equation 16.23, the hydraulic conductivity, Lp, can be determined experimentally as:

(16.71)

(16.71)

The osmotic permeability, Pf, can then be calculated as Pf=LpRT/ w (Equation 16.36). The experimentally determined values reflect the rate of water flow, Qv, in the presence of a known osmotic pressure difference, Δπ, produced by a solution with a known reflection coefficient, σ≈1.0, over a known surface area, A.

w (Equation 16.36). The experimentally determined values reflect the rate of water flow, Qv, in the presence of a known osmotic pressure difference, Δπ, produced by a solution with a known reflection coefficient, σ≈1.0, over a known surface area, A.

The rate of water movement into or out of erythrocytes in response to mixing with hypertonic or hypotonic media has been measured by using light scattering as an index of erythrocyte volume. The experiments are similar to those used to determine Pd; a suspension of erythrocytes is mixed with media of defined osmolality and the mixture then flows down a tube passing through an observation cell. Light scattering is monitored at known distances down the tube and cell volume changes are calculated from changes in light scattering. This and other methods give values for Lp that cluster around 1.8×10−11 cm3·dyn−1·s−1 (Solomon, 1989). Using R = 8.314×107 dyn·cm·mol−1·K−1,  = 18 cm3·mol−1 and T = 298 K, this average value of Lp corresponds to a Pf of about 2.5×10−2 cm·s−1.

= 18 cm3·mol−1 and T = 298 K, this average value of Lp corresponds to a Pf of about 2.5×10−2 cm·s−1.

VC Water Channels in Biological Membranes

The ratio of Pf/Pd for the erythrocyte membrane described earlier is about 5. Although there is some uncertainty in this ratio, it is clearly in excess of the value of 1.0 predicted for a diffusive mechanism. This suggests that there are pores in the erythrocyte membrane. The actual value of Pf/Pd for the pore alone cannot be obtained from just this information, however, because the erythrocyte membrane is actually a mosaic of lipid bilayer and pores; water moves through both in parallel, so the permeabilities of the components add. Experiments that block the pore suggest that the Pf/Pd ratio for the pore alone is about 10 and that 90% of water flux is via the pore, whereas 10% crosses the lipid bilayer (Macey, 1979; Finkelstein, 1987).

Two distinct means of inhibiting water transport provide additional evidence for proteinaceous pores. Mercurial sulfhydryl reagents, such as HgCl2, p-chloromercuribenzoate (PCMB) and p-chloromercuribenzene sulfonate (PCMBS), decrease the erythrocyte Pf by a factor of 10 and Pd by less than a factor of 2 and the osmotic and diffusional permeabilities become equal (Macey and Farmer, 1970; Macey et al., 1972). Concurrently, the activation energy for permeation is increased from about 4 kcal·mol−1 expected for water-filled pores to >10 kcal·mol−1, a value typical of artificial lipid bilayers (see Table 16.2). Mercurials inhibit water transport primarily by targeting protein SH groups because their effect is fully and rapidly reversed by cysteine. The second inhibitor is radiation. High doses of radiation inhibit water transport in both erythrocytes (van Hoek et al., 1992) and renal brush-border membrane vesicles (van Hoek et al., 1991). The characteristics of radiation inactivation suggest that the target is the size of a 30-kDa protein and are inconsistent with the entire membrane or transient defects serving as the major water pathway.

Although these studies and others, especially in epithelia (e.g. Verkman, 1993), made it clear that water pores or channels must exist, until recently, their identity and characteristics remained mysterious. Are what we call “water channels” simply water moving through open ion channels or through an ion exchanger or ion co-transporter? Are water channels specific, admitting water but excluding ions? These questions have been answered with the cloning and expression of a family of water channels called aquaporins (Agre et al., 1993; King and Agre, 1996; Verkman et al., 1996; Heymann et al., 1998; Nielsen et al., 1999).

VC1 Aquaporins

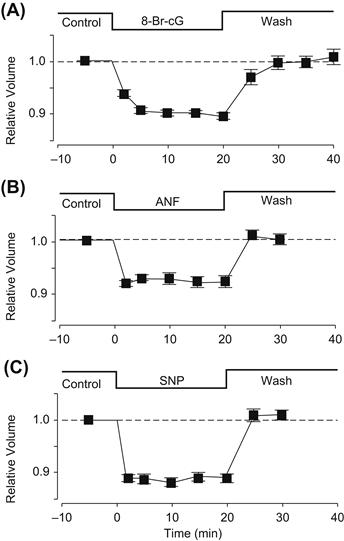

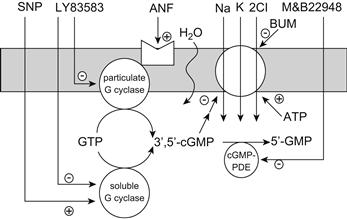

Water channels are related to the membrane integral protein (MIP) family (20–40% homology). The first water channel identified was cloned from a human bone marrow library by Preston and Agre (1991) based on the sequence of a purified protein of uncertain function. Initially called CHIP28 (channel-forming integral protein, 28 kDa), this protein was later redesignated aquaporin-1 (AQP1) and MIP-1 is referred to as AQP0. Ten mammalian aquaporins are known and more than 100 related proteins have been found in amphibians, Drosophila, plants, Escherichia coli and yeast, but not all of these conduct water (Heyman et al., 1998; Nielsen et al., 1999; Heymann and Engel, 1999).