Chapter 23

Regulation of Cardiac Ion Channels by Cyclic Nucleotide-Dependent Phosphorylation

Chapter Outline

III. Regulation of the Cardiac L-Type Ca2+ Channels by Cyclic AMP

IIIA. Evidence for Cyclic AMP Modulation of L-Type Ca2+ Channel Function

IIIB. The Phosphorylation Hypothesis

IV. Regulation of the L-Type Ca2+ Channels by Cyclic GMP

I Summary

Ion channels in the heart are regulated by many physiological mechanisms. One of the most important mechanisms is the regulation by cyclic nucleotide protein kinases. Calcium channels in the heart play a central role in excitation–contraction coupling and the physiological modulation of these channels is crucial to the functioning of the heart under differing conditions. Phosphorylation–dephosphorylation reactions regulate the cardiac calcium channel activity. Activation of the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase stimulates the channel activity, whereas activation of the cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits the channel activity. Both synthesis and degradation of the cyclic nucleotides are regulated by a large number of physiological and pathophysiological first messengers. There is considerable compartmentalization of the components of the cyclic nucleotide pathways and there are significant interactions between the two cyclic nucleotides. The complexities of these two cyclic nucleotide systems allows for fine control of calcium channel activity in the heart.

II Introduction

Phosphorylation of ion channel proteins by various protein kinases is one of the primary mechanisms for physiological modulation of ion channel activity. One of the most widely-studied examples of this regulatory mechanism is cyclic nucleotide-dependent phosphorylation of the calcium channels in the heart.

There exist several different subtypes of voltage (V)-dependent Ca2+ channels in excitable cells. In cardiac muscle cells, the primary channels responsible for entry of Ca2+ ions into the cell during an action potential (AP) are the V-dependent “L-type” (i.e. “long-lasting”) Ca2+ channels responsible for the L-type Ca2+ current (ICa). This chapter will focus on the L-type Ca2+ channel of cardiac myocytes and modulation of ICa by the cyclic nucleotide-dependent phosphorylation, in order to illustrate some important principles that are involved in ion channel regulation.

The L-type channels play a central role in excitation–contraction (E-C) coupling. During an AP, Ca2+ influx through the L-type channels leads to: (1) direct activation of the myofilaments; (2) Ca2+ loading of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR); and (3) release of Ca2+ from the SR (“calcium-induced calcium release”). Thus, controlling the amount of Ca2+ influx through the L-type channels is a key mechanism for regulation of myocardial contractility.

The L-type Ca2+ channels have some special properties, including functional dependence on metabolic energy, selective blockade by acidosis and regulation by intracellular second messengers. Because of these special properties of these channels, Ca2+ influx into the myocardial cell can be controlled by both extrinsic factors (such as autonomic nerve stimulation or circulating hormones) and intrinsic factors (such as intracellular pH or ATP levels). Thus, there are many sites for physiological and pathophysiological modulation of ICa.

III Regulation of the Cardiac L-type Ca2+ Channels by Cyclic AMP

IIIA Evidence for Cyclic AMP Modulation of L-type Ca2+ Channel Function

A major physiological modulator of ion channels and E-C coupling in the heart is the β-adrenergic pathway. It has long been known that the β-adrenergic-cAMP pathway modulates the functioning of the L-type Ca2+ channels (Shigenobu and Sperelakis, 1972; Tsien et al., 1972) (Fig. 23.1). Every step in the pathway has been shown to alter ICa. Stimulation of cardiac β-adrenergic receptors (e.g. in response to the release of norepinephrine from sympathetic nerves) causes adenylate cyclase activation. This results in increase of intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels and enhanced activation of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PK-A). The activated PK-A phosphorylates a number of proteins, including several involved in E-C coupling (e.g. Stojanovic et al., 2001).

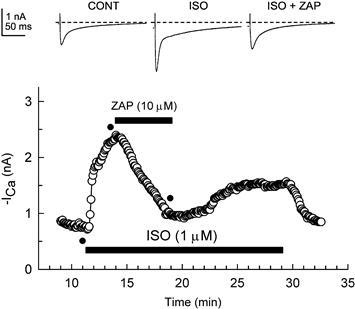

FIGURE 23.1 Zaprinast inhibited the isoproterenol-stimulated ICa. Shown are the original currents (upper panel) and the amplitude of ICa at 0 mV over time (lower panel) during superfusion of the cells with control (CONT), 1 μM isoproterenol-containing (ISO), or isoproterenol plus 10 μM zaprinast-containing (ISO + ZAP) solutions. Superfusion of the cell with 1 μM isoproterenol caused a large stimulation of ICa. Subsequent superfusion of the cell with 10 μM zaprinast caused a substantial inhibition of the isoproterenol-induced stimulation of ICa. Upon washout of zaprinast there was a partial recovery of the isoproterenol-stimulated ICa. Standard whole-cell recording (calcium-free pipette solution) was used. Individual current traces were obtained at time points indicated by the filled circles in the lower panel. (From Ziolo et al., 2003; used with permission).

Thus, induction of Ca2+-dependent slow APs, an indirect measure of ICa, was observed with exposure to direct activators of adenylate cyclase (forskolin, Gpp(NH)p) (Josephson and Sperelakis, 1978; Wahler and Sperelakis, 1986). These effects have been repeatedly confirmed by direct measurement of adenylate cyclase activators on ICa (e.g. Ziolo et al., 2003; Fig. 23.2). Additionally, direct injection of cAMP into ventricular muscle cells was shown rapidly to (within seconds) induce Ca2+-dependent slow APs (Vogel and Sperelakis, 1981; Li and Sperelakis, 1983; Bkaily and Sperelakis, 1985) and enhance ICa (Irisawa and Kokubun, 1983). Similarly, rapid enhancement of ICa was observed with intracellular photochemical activation of cAMP in ventricular myocytes (Nargeot et al., 1983). Other neurotransmitters, hormones and autacoids that stimulate cAMP production (e.g. histamine) also enhance ICa.

FIGURE 23.2 Zaprinast inhibition of the forskolin-stimulated ICa in the absence and presence of an inhibitor of PK-G (KT5823). Superfusion of a cell with 0.3 μM forskolin (FORSK), a direct activator of adenylate cyclase, caused a large stimulation of ICa. Upper panel: under control conditions, subsequent superfusion of the cell with 10 μM zaprinast (ZAP) caused a substantial reversible inhibition of the forskolin-induced stimulation of ICa. Lower panel: in contrast, in the presence of 0.1 μM KT5823 (KT), the inhibitory effect of zaprinast was greatly attenuated. Standard whole-cell recording was used. (Modified from Ziolo et al., 2003; used with permission).

Since PK-A phosphorylation of the L-type Ca2+ channels leads to an increase in ICa and enhanced Ca2+ influx during the plateau phase of the AP, this causes a direct increase in the amount of Ca2+ available to the contractile proteins. It also indirectly increases the Ca2+ available to the contractile proteins due to effects of increased Ca2+ influx on Ca2+ cycling and release by the SR. The direct and indirect effects of the phosphorylated L-type Ca2+ channel, together with the effects of PK-A-phosphorylated SR proteins, mediate the vast majority of the positive inotropic effects of β-adrenergic stimulation on the heart.

Single-channel analysis indicates that β-adrenergic stimulation causes an increase in the mean open time of Ca2+ channels and increases the probability of opening (largely by decreasing interval between bursts of openings), whereas the single-channel conductance is unaffected (Reuter et al., 1982; Klein et al., 2000). These effects on the channels lead to an increased ICa during the AP.

IIIB The Phosphorylation Hypothesis

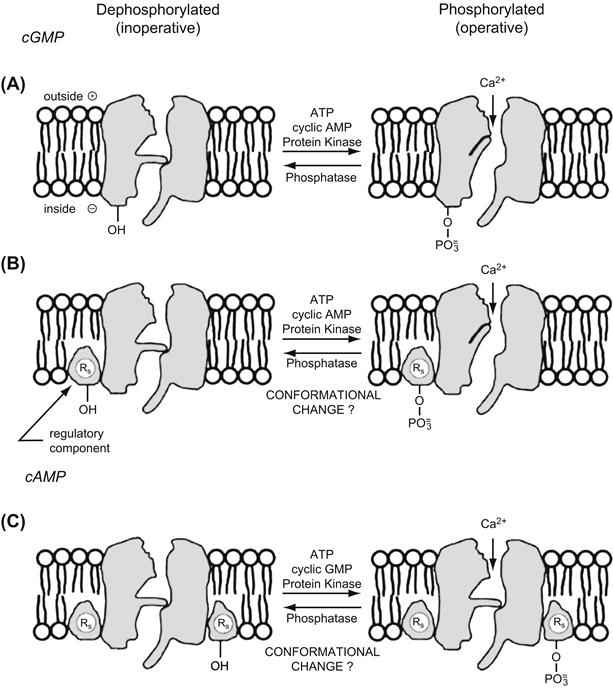

Because of the relationship between cAMP and the number of available L-type Ca2+ channels and because of the metabolic dependence of the functioning of these channels, it was hypothesized that one of the proteins that is phosphorylated is the L-type Ca2+ channel protein (or a contiguous regulatory protein). That is, the L-type channel must be phosphorylated for it to become available for voltage activation (Shigenobu and Sperelakis, 1972; Tsien et al., 1972). According to the phosphorylation hypothesis (Fig. 23.3 ), agents that elevate cAMP increase the fraction of the channels that are in the phosphorylated form and hence readily available for voltage activation. Whatever the precise molecular mechanism for the effect phosphorylation has on channel activity, in the phosphorylation model, the phosphorylated form of the L-type channel is the active (operational) form and the dephosphorylated form is the inactive (inoperative) form. The dephosphorylated channels are virtually silent electrically (i.e. their opening probability approaches zero). Phosphorylation increases the probability of channel opening with depolarization. An equilibrium should exist between the phosphorylated and dephosphorylated forms of the channel under a given set of conditions.

FIGURE 23.3 The phosphorylation hypothesis. Schematic model for an L-type Ca2+ channel in myocardial cell membrane in two hypothetical forms: dephosphorylated (or electrically silent) form (left diagrams) and phosphorylated form (right diagrams). The two gates associated with the channel are an activation gate and an inactivation gate. The phosphorylation hypothesis states that a protein constituent of the Ca2+ channel itself (A) or a regulatory protein associated with the channel (B) must be phosphorylated for the channel to be in a state available for voltage activation. Phosphorylation of a serine (or threonine) residue occurs by PK-A in the presence of ATP. Phosphorylation may produce a conformational change that effectively allows the channel gates to operate. The L-type channel (or an associated regulatory protein) may also be phosphorylated by PK-G (C), thus mediating the inhibitory effects of cGMP on the Ca2+ channel. (Adapted from Sperelakis and Schneider, 1976).

IIIC Protein Kinase-A (PK-A ) Activation

Over the years, considerable evidence has accumulated that supports the phosphorylation hypothesis. For example, intracellular injection of the catalytic subunit of PK-A induces and increases the slow Ca2+-dependent APs and potentiates ICa (Osterreider et al., 1982; Bkaily and Sperelakis, 1984). Injection of a PK-A inhibitor protein into heart cells inhibits slow Ca2+-dependent APs and ICa (Bkaily and Sperelakis, 1984; Kameyama et al., 1986). These results verify that the regulatory effect of cAMP on ICa is mediated by PK-A and phosphorylation.

Also consistent with the phosphorylation hypothesis, L-type Ca2+ channel activity disappears within 90 s in isolated membrane inside-out patches, but can be restored (in neurons) by applying the catalytic subunit of PK-A together with MgATP (Armstrong and Eckert, 1987). This is consistent with the washing away of regulatory components of the Ca2+ channels or of the enzymes necessary to phosphorylate the channel. Even in whole-cell voltage-clamp, there is a progressive run-down of the Ca2+ current, which is slowed or partially reversed by conditions that enhance PK-A phosphorylation.

IIID Phosphatases

While much research has been done on the role of phosphorylation in the regulation of ion channels, much less is known about the reverse reaction, i.e. the role of dephosphorylation of ion channels by phophatases. Based on the rapid decay of the response to microinjected cAMP, the mean life span of a phosphorylated channel is probably only a few seconds at most. Agents that affect or regulate the phosphatase that dephosphorylates the channel would affect the life span of the phosphorylated channel. Thus, channel stimulation can be produced either by increasing the rate of phosphorylation (by PK-A activation) or by decreasing the rate of dephosphorylation (inhibition of the phosphatase).

In ventricular cells, several phosphatases have been shown to inhibit ICa (e.g. Kameyama et al., 1986; duBell and Rogers, 2004), consistent with the phosphorylation hypothesis. Additionally, phosphatase inhibitors, such as okadaic acid and microcystin, cause large increases in ICa (Hescheler et al., 1987, 1988; Frace and Hartzell, 1993). There is some disagreement about the relative effectiveness of specific phosphatases (particularly type 1 versus type 2A) in reducing ICa and whether basal ICa is significantly inhibited by phosphatases, or if only the cAMP-stimulated ICa (e.g. by a β-adrenergic agonist) is affected.

Protein phosphatase-type 1 activity is inhibited by (at least) two low-molecular-weight proteins, protein phosphatase inhibitor-1 (PPI-1) and protein phosphatase inhibitor-2 (PPI-2). PPI-1 is present in ventricular myocytes and it may be an important additional component of the modulation of the phosphorylation–dephosphorylation cycle of the L-type channel. The activity of PPI-1 is enhanced by phosphorylation with PK-A (Ahmad et al., 1989; Gupta et al., 1996). Thus, PK-A not only phosphorylates the Ca2+ channel, it also decreases the rate of channel dephosphorylation. Both actions stimulate channel activity.

In contrast to the effects of other phosphatases examined to date, calcineurin has been shown to enhance ICa (Tandan et al., 2009). Calcineurin binds to the L-type Ca2+ channel near the site where PP2A binds and dephosphorylates the channel but, unlike PP2A, calcineurin upregulates channel activity. Additionally, calcineurin inhibitors inhibit ICa. Thus, while dephosphorylation of the Ca2+ channel does not always inhibit ICa, it does appear that phosphatases are an additional important determinant of the amplitude of ICa. Alternatively, there may be more than one site on the channel that can be phosporylated.

IV Regulation of the L-type Ca2+ Channels by Cyclic GMP

IVA Cyclic GMP Effects

The physiological role played by cyclic GMP (cGMP) on cardiac function appears to be more complex than that of cAMP. It was originally proposed that cGMP plays a role antagonistic to that of cAMP (Goldberg et al., 1975) and, in most instances, but not all, this appears to be the case. Thus, considerable evidence has accumulated demonstrating cGMP inhibition of ICa. For example, 8-Br-cGMP, a more permeable and hydrolysis-resistant analog of cGMP, has been shown to shorten the AP duration in rat atria (accompanied by a negative inotropic effect) (Nawrath, 1977) and to inhibit Ca2+-dependent slow APs (Kohlhardt and Haap, 1978; Wahler and Sperelakis, 1985) and accompanying contractions (Wahler and Sperelakis, 1985). Intracellular injection of cGMP into atrial, ventricular and Purkinje fiber preparations was also shown rapidly to depress or abolish slow APs (Mehegan et al., 1985; Wahler and Sperelakis, 1985).

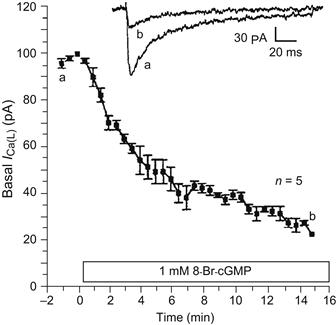

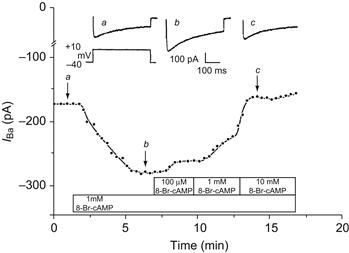

In whole-cell voltage-clamp experiments on single cardiomyocytes from a variety of species, it has been directly shown that cGMP regulates ICa (e.g. Fischmeister and Hartzell, 1987; Levi et al., 1989, 1994; Wahler et al., 1990; Mery et al., 1991; Wahler and Dollinger, 1995; Sumii and Sperelakis, 1995; Ziolo et al., 2003) (Fig. 23.4). For example, in voltage-clamp experiments on single ventricular cardiomyocytes from embryonic chicks or neonatal rats, stimulation of ICa produced by 8-Br-cAMP added to the bath could be completely reversed by the addition of 8-Br-cGMP (Masuda and Sperelakis, unpublished observations; Fig. 23.5). The ratio of cAMP/cGMP apparently determines the degree of stimulation of ICa.

FIGURE 23.4 Time course of the inhibition of the basal ICa by 8-Br-cGMP (1 mM) in 17-day-old embryonic chick heart cells. Data points plotted are the mean ± standard error. The upper two traces show the original current recordings of ICa taken at the time points shown by the corresponding letters in the graph. ICa was elicited by 200 ms depolarizing pulses to +10 mV from a holding potential of −45 mV. Experiments conducted at room temperature. (From Haddad et al., 1995.)

FIGURE 23.5 Antagonism of the stimulating effect of 8-Br-cAMP on ICa by 8-Br-cGMP in a single 2-day rat ventricular myocyte. Upper tracings show three original current recordings of ICa corresponding to the three time points labeled in the lower graph. ICa was elicited by 300 ms depolarizing pulses to +10 mV from a holding potential of −40 mV. Ba2+ (20 mM) was used as the charge carrier. Experiments conducted at room temperature of 25°C. (From Masuda and Sperelakis, unpublished.)

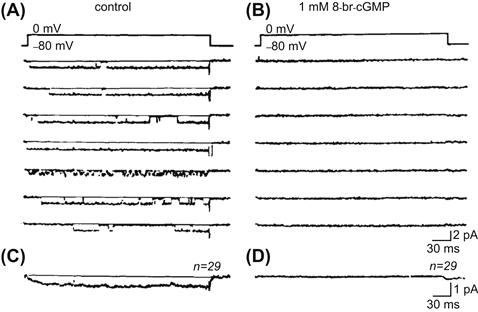

In some instances, the cGMP inhibition of ICa is dependent on prior stimulation of ICa by cAMP. However, it has also been directly demonstrated that, under some conditions, 8-Br-cGMP inhibits basal ICa (i.e. unstimulated by cAMP) in voltage-clamped ventricular myocytes (e.g. Wahler et al., 1990; Haddad et al., 1995) (see Fig 23.4). Inhibition of basal Ca2+ channel activity by cGMP has also been demonstrated at the single-channel level in embryonic chick heart (Tohse and Sperelakis, 1991) (Fig. 23.6), under conditions in which the intracellular environment is likely to be more normal than during whole-cell voltage clamp experiments. Addition of 8-Br-cGMP to the bath completely inhibited Ca2+ channel activity. Cyclic GMP did not change the conductance of the Ca2+ channel, but prolonged the closed times and shortened the open times. In contrast, 8-Br-cGMP had no effect on the basal Ca2+ single-channel activity in mouse ventricular myocytes, but did reverse all the stimulatory effects of the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol (Klein et al., 2000). However, the debate about whether basal ICa is inhibited by cGMP is likely more of academic than physiological importance, since in vivo there would consistently be tonic activation of β-adrenergic receptors due to sympathetic nerve activity and adrenal release of catecholamines. Under such conditions, no true “basal” (i.e. unstimulated by cAMP) ICa would exist.

FIGURE 23.6 Current recordings from a cell-attached patch showing the effect of 8-Br-cGMP on the Ca2+ channel activity in a single myocardial cell isolated from a 3-day-old embryonic chick heart. Single channel currents were evoked by depolarizing voltage pulses to 0 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV, at a duration of 300 ms and stimulation frequency of 0.5 Hz. (A and B) Examples of original current recordings from the same patch, before (A) and after (B) superfusion with 1.0 mM 8-Br-cGMP. (C and D) Ensemble-averaged currents calculated from the current recordings (n = 29 traces). (Data from Tohse and Sperelakis, 1991.)

IVB Mechanisms for cGMP Inhibition of ICa

As noted above, cGMP regulates the functioning of the L-type Ca2+ channels in a manner that is antagonistic to that of cAMP. It was hypothesized that the Ca2+ channel protein has a second site that can be phosphorylated by the cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PK-G) and that, when phosphorylated, inhibits the Ca2+ channel (Wahler and Sperelakis, 1985). Another possibility is that there is a second type of regulatory protein that is inhibitory when phosphorylated (see Fig. 23.3). Subsequently, it was shown that, similar to activated PK-A, activated PK-G phosphorylates a number of proteins involved in E-C coupling (e.g. Stojanovic et al., 2001), including the L-type Ca2+ channel (Schröder et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2007).

There is considerable evidence that the PK-G-mediated phosphorylation of the L-type Ca2+ channel is functionally significant, i.e. that the reduction of ICa observed with cGMP is mediated by this phosphorylation (at least in mammalian and avian ventricular myocytes; see below). Observation of inhibition of ICa by 8-Br-cGMP (see Figs. 23.4–23.6), which is a potent activator of PK-G, supports the view that PK-G is responsible for the inhibitory effect of cGMP on ICa.

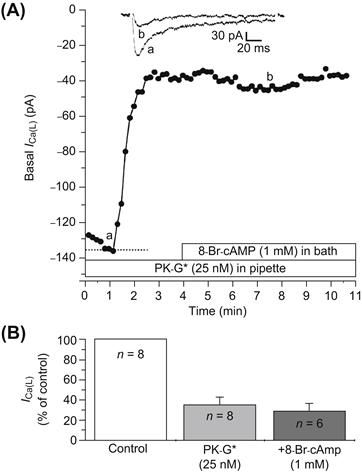

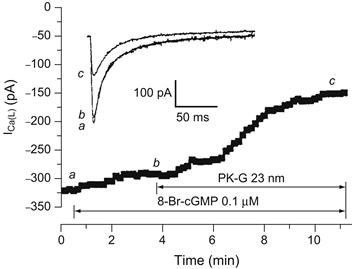

In some preparations (e.g. embryonic chick, neonatal rat), when PK-G is directly added to the patch pipette for diffusion into the cell during whole-cell voltage clamp, basal ICa is inhibited markedly and rapidly, with maximum inhibition reached in about 3–5 min (Fig. 23.7). Note that inhibition of basal ICa began about 80 s after breaking into the cell. Similar effects of PK-G infusion were observed in early neonatal rat ventricular myocytes, as illustrated in Fig. 23.8 (Sumii and Sperelakis, 1995). As can be seen, there is a rapid and prominent inhibition of basal ICa by PK-G. Addition of H-8 (a blocker of both PK-A and PK-G) to the bath often causes a rapid restoration of ICa to about the original basal level. Addition of 1 mM 8-Br-cAMP can produce only a small stimulation of ICa in the continued presence of PK-G (see Fig. 23.8). Therefore, these findings indicate that the inhibitory effects of cGMP on ICa in mammalian and avian ventricular myocytes are mediated by activation of PK-G and resultant phosphorylation. Because 8-Br-cGMP is a potent activator of PK-G and does not stimulate cAMP hydrolysis, cGMP-induced inhibition of the basal activity of the Ca2+ channels (not prestimulated by cAMP) is likely also to be mediated by PK-G.

FIGURE 23.7 Inhibition of basal ICa of 17-day-old embryonic chick cardiomyocytes by PK-G. (A) PK-G (25 nM) was present in the patch pipette for diffusion into the cell during whole-cell voltage clamp. Inhibition of ICa began within 70 s after breaking into the cell and reached maximum at about 2.5 min. Addition of 1 mM 8-Br-cAMP into the bath failed to reverse the inhibition produced by PK-G. The two current traces illustrated at the top correspond to the time points labeled a and b in the graph. (B) Bar graph summary of the inhibition of basal ICa by PK-G in eight cells, and the lack of reversal by 8-Br-cAMP in six cells. Experiments were done at room temperature. (From Haddad et al., 1995.)

FIGURE 23.8 Inhibition of basal ICa by PK-G (25 mM) in a ventricular myocyte from an early (4 day) neonatal rat heart. Time course of the effect of low doses of 8-Br-cGMP (0.1 μM) and PK-G (25 nM) on basal (not stimulated) ICa. 8-Br-cGMP and PK-G were applied using the perfusion patch-pipette technique. As shown, when 8-Br-cGMP was applied in advance of PK-G, it had only a little effect, whereas subsequent addition of PK-G produced rapid inhibition (inset). Selected current traces of ICa (a, b, and c) at points denoted on the time course curve. (Reproduced with permission from Sumii and Sperelakis, 1995.)

In ventricular muscle from wild-type mice, 8-Br-cGMP inhibited contractility, consistent with observations in other cardiac preparations. In addition, in the same study (Wegener et al., 2002), 8-Br-cGMP had no effect on contractility in PK-G-1 knockout mice, supporting the view that PK-G mediated the inhibition of contractility caused by 8-Br-cGMP. In contrast, muscarinic cholinergic stimulation reduced myocyte contractility, not only in wild-type, but also in the PK-G-1 knockout mouse, suggesting that muscarinic inhibition of contractility may be independent of PK-G-1 activation.

In single-channel recordings in mouse ventricular myocytes, 8-Br-cGMP has no effect on basal single Ca2+ channel activity, but reverses all the stimulatory effects of the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol (Klein et al., 2000). This inhibitory effect of 8-Br-cGMP is also blocked by a PK-G inhibitor, indicating that the effect is mediated by PK-G.

The effects of cardiac myocyte-selective overexpression of PK-G 1 (the primary isoform of PK-G in cardiac myocytes) on the Ca2+-channel response to cGMP have also been investigated at the single-channel level (Schröder et al., 2003). 8-Br-cGMP, DEA-NO (an NO donor) and carbachol (a muscarinic agonist) all inhibited the β-adrenergic stimulation of L-type Ca2+ activity in wild-type mouse ventricular myocytes. This inhibition of channel activity was dramatically enhanced for 8-Br-cGMP and DEA-NO (but not carbachol) in the myocytes from mice that overexpressed PK-G 1. Furthermore, while none of the three agents had any effect on the basal L-type Ca2+ channel activity in myocytes from wild-type mice, in myocytes overexpressing PK-G 1, 8-Br-cGMP and DEA-NO (but not carbachol) had a dramatic inhibitory effect on basal L-type channel activity. These data again support the hypothesis that the inhibitory effects of 8-Br-cGMP and NO are mediated by PK-G 1, but not the inhibitory effects of muscarinic agonists.

There is another mechanism for cGMP inhibition of ICa that has been reported for some preparations. This indirect mechanism involves cGMP stimulation of PDE 2, leading to an anti-adrenergic effect due to a reduction in cAMP levels. Evidence for this mechanism comes primarily from frog ventricular myocytes, in which intracellular application of cGMP inhibited ICa only after the cAMP levels had been increased and EHNA (a selective PDE 2 inhibitor) blocked the cGMP inhibition (Hartzell and Fischmeister 1986; Fischmeister and Hartzell, 1987). It was concluded that cGMP activates PDE 2 (a cGMP-stimulated isoform of phosphodiesterase), resulting in degradation of cAMP. This cGMP-stimulated PDE mechanism for inhibition of ICa was also found to occur in human atrial cells (Rivet-Bastide et al., 1997).

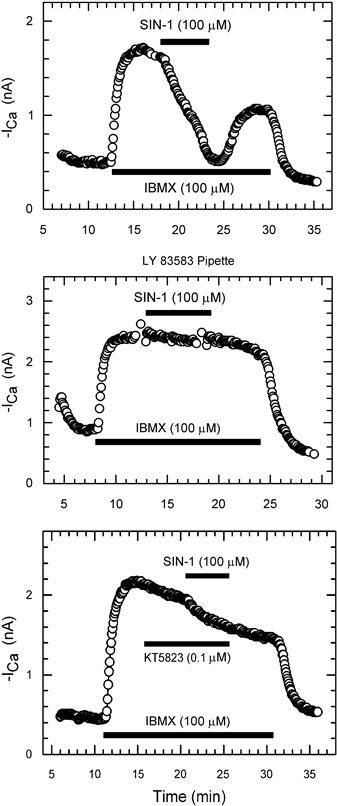

However, this mechanism (cGMP stimulation of PDE) for cGMP inhibition of ICa does not appear to be present in mammalian ventricular myocytes. For example, EHNA has no effect on basal or β-stimulated ICa in mammalian ventricular myocytes (Rivet-Bastide et al., 1997). In mammalian and avian ventricular myocytes, the inhibition of ICa by cGMP is not mediated by PDE 2, but rather by PK-G (Levi et al., 1989; Wahler et al., 1990; Mery et al., 1991; Wahler and Dollinger, 1995). 8-Br-cGMP (which does not stimulate PDE 2), not only inhibits slow APs in mammalian cardiac muscle, but it does so without decreasing cAMP levels (Thakkar et al., 1989). Additionally, the inhibitory effect on ICa of agents that elevate cGMP is maintained when there is a general inhibition of PDEs, including PDE 2, with a non-specific PDE inhibitor (IBMX) (Fig. 23.9). In contrast, the anti-adrenergic action of cGMP is blocked by KT5823, a selective inhibitor of PK-G (Wahler and Dollinger, 1995; Ziolo et al., 2003; see Figs. 23.2 and 23.9).

FIGURE 23.9 Blockade of SIN-1 inhibition of ICa by LY-83583 or KT5823. Top panel: shown is an example of SIN-1 (100 μM) inhibition of IBMX-enhanced ICa under control conditions. Central panel: inclusion of 10 μM LY-83583 in the pipette solution virtually abolished the response to SIN-1. Bottom panel: superfusion of the cell with 0.1 μM KT5823 had little effect on IBMX-stimulated ICa, but greatly reduced the effect of SIN-1. (Modified from Wahler and Dollinger, 1995; used with permission.)

IVC Effects of Nitric Oxide on ICa

Nitric oxide (NO) is known to be an important regulator of a variety of cellular functions, including contractility of the heart. Many (though not all) of the effects of NO are mediated through stimulation of soluble guanylate cyclase (G-cyclase) activity and the resulting enhanced cGMP production. As numerous studies have shown that cGMP inhibits ICa in cardiac myocytes, the depression of contractility by NO may be in large part due to a cGMP-mediated inhibition of ICa.

Due to the highly labile nature of NO, NO donors are often used to examine the effect of NO. The NO donor SIN-1 has been shown to have an anti-adrenergic effect on ICa in both frog and mammalian ventricular myocytes (Mery et al., 1993; Wahler and Dollinger, 1995), similar to the effects of cGMP. The spontaneous breakdown of SIN-1 in solution, not only generates NO, but also generates superoxide anions which can inactivate NO and lead to formation of peroxynitrite, a strong oxidizing agent. Thus, SIN-1 is also used as a peroxynitrite donor and the effects of SIN-1 observed on ICa could be caused by peroxynitrite, rather than by NO. The addition of superoxide dismutase and catalase, which should degrade superoxide (thereby protecting NO and minimizing peroxynitrite formation) enhanced the effects of SIN-1 on ICa (Wahler and Dollinger, 1995). Furthermore, LY83583, which blocks cGMP formation by G-cyclase (Kontos and Wei, 1993), or KT5823, which inhibits PK-G, nearly abolished the ICa response to SIN-1 (see Fig. 23.9). Together these results strongly suggest that NO, rather than peroxynitrite, mediates the effects of SIN-1 on ICa and that this occurs through enhanced activity of PK-G.

Although in the virtual absence of intracellular (pipette) Ca2+, SIN-1 was reported to have no effect on ventricular ICa, when a physiological concentration of Ca2+ (pCa = 6.85) was present in the pipette solution, SIN-1 did reduce basal ICa (Matsumoto, 1997). Thus, it is clear that cGMP can also inhibit basal ICa at least in some preparations under physiological intracellular conditions.

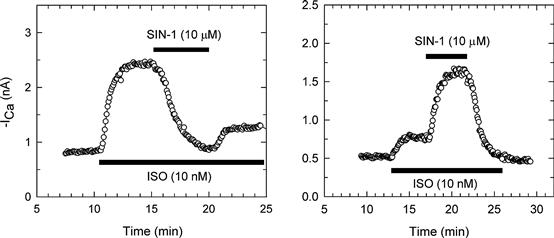

SIN-1, in addition to producing a prominent inhibitory (anti-adrenergic) effect, can occasionally cause an enhancement of ICa in frog and mammalian ventricular myocytes (Mery et al., 1993; Wahler and Dollinger, 1995). Thus, in cells in which the response to β-agonists was relatively small, low doses of SIN-1 sometimes caused a stimulation of ICa rather than an inhibition (Fig. 23.10). A similar enhancement of β-stimulated ICa by low doses of pipette cGMP had been reported previously (Ono and Trautwein, 1991). Thus, while NO and cGMP generally have an inhibitory effect on ICa, in some instances, they can actually enhance the response to β-stimulation of ICa. The stimulatory effect of SIN-1 occasionally observed is likely to be mediated by the same mechanism thought to be responsible for cGMP stimulation of cAMP-enhanced ICa previously described for guinea pig ventricular myocytes, i.e. cGMP inhibition of the cGMP-inhibited PDE (Ono and Trautwein, 1991).

FIGURE 23.10 SIN-1 inhibition and stimulation of isoproterenol (ISO)-enhanced calcium current (ICa). Shown are time courses of ICa response during superfusion of cells with control (CONT), 10 nM ISO, and IS0 plus 10 μM SIN-1 (IS0 + SIN-1) bath solutions. Currents were recorded at 0 mV. Left panel: in this cell, 10 nM IS0 had a large effect on ICa, and subsequent exposure to 10 μM SIN-1 caused a considerable inhibition of ISO-enhanced ICa. ICa partially recovered following washout of SIN-1 with IS0 solution. Right panel: in another cell, the response to 10 nM IS0 was quite small, compared with the left panel example, and exposure to 10 μM SIN-1 substantially increased ISO-enhanced ICa. (Modified from Wahler and Dollinger, 1995; used with permission.)

IVD Pathophysiological Effects of Nitric Oxide/cGMP

Nitric oxide is synthesized by nitric oxide synthase (NOS) from L-arginine. NOS exists in three isoforms, neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS-1 or nNOS), inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS-2 or iNOS), and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS-3 or eNOS) (Alderton et al., 2001). The constitutive isoforms of NOS (NOS-1 and NOS-3) produce relatively small amounts of NO in a Ca2+-dependent fashion (Xie and Nathan, 1994). In cardiac myocytes, constitutive NOS (primarily eNOS) is normally present and functional (Schulz et al., 1992). In contrast, iNOS (which produces much more NO than the constitutive isoform and for longer periods of time) is not normally present in most types of cells, including cardiac myocytes. However, it is expressed in cardiac myocytes under pathological conditions that involve exposure of the cells to cytokines. Thus, it may be that NO produced by constitutive NOS mediates the physiological effects of NO, whereas the much higher levels of NO produced by iNOS may mediate the pathophysiological actions of NO in a number of pathological conditions of the heart. For example, pre-exposure of guinea pig ventricular myocytes to IL-1β for several hours has an anti-adrenergic effect on ICa that is L-arginine-dependent and NO-mediated (Rozanski and Witt, 1994).

Transplanted hearts are exposed to a variety of cytokines during rejection and have an increased NO production and depressed contractility. Myocytes isolated from rejecting hearts exhibit parallel increases in NO (and cGMP) production (due to the expression of the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase) (Yang et al., 1994; Ziolo et al., 1998) and both a reduced basal contraction and inotropic response to β-adrenergic stimulation (Pyo and Wahler, 1995; Ziolo et al., 1998). The reduced contractile function is due to an NO/cGMP-mediated inhibition of ICa. Thus, ICa is reduced in myocytes from rejecting transplanted rat hearts (allografts) compared to myocytes from non-rejecting transplanted control hearts (isografts) (Ziolo et al., 2001). This reduction in ICa in the allograft myocytes is dependent on L-arginine (the precursor of NO). Additionally, aminoguanidine (a selective inhibitor of the inducible nitric oxide synthase) and KT5823 (a selective inhibitor of PK-G) rapidly reversed the elevated NO and cGMP production, the inhibition of ICa and the contractile depression in allograft myocytes, but had no effect on ICa or contraction of isograft myocytes (Ziolo et al., 1998, 2001). In human transplant patients, expression of iNOS in rejecting hearts correlates with increased cGMP levels and depressed contractility (Lewis et al., 1996; Paulus et al., 1997).

V Phosphodiesterases

VA cAMP PDEs

The hydrolysis of cyclic nucleotides occurs via phosphodiesterases (PDEs). There are 11 isoform families of these enzymes that hydrolyze cAMP and/or cGMP, of which PDEs 2-5 seem to be the most important ones for cyclic nucleotide regulation in cardiac myocytes (for review see Fischmeister et al., 2006). Previous studies have found that inhibitors of PDEs, not only can increase basal ICa, they can also potentiate the effect of β-adrenergic stimulation on ICa (e.g. Fischmeister and Hartzell, 1991; Mubagwa et al., 1993; Kawamura and Wahler, 1994; Wahler and Dollinger, 1995; Kajimoto et al., 1997; Verde et al., 1999). Thus, it is clear that both the synthesis and the rate of hydrolysis of cAMP are important in regulating ICa.

It should be noted that cGMP interacts with several isoforms of PDE that preferentially hydrolyze cAMP. Thus, the activity PDE 2 (the PDE responsible for the anti-adrenergic effects of cGMP in frog ventricular myocytes) is stimulated by cGMP. In addition, PDE 3 is a cGMP-inhibited PDE and it is this PDE which appears to mediate the positive (stimulatory) effect of cGMP on ICa.

VB cGMP PDE

Of the multiple isoforms of PDE, some preferentially degrade cAMP, whereas others hydrolyze both cAMP and cGMP equally. One family of isoforms (PDE 5) preferentially hydrolyzes cGMP (for review, see Francis et al., 2010). The inhibitory action of exogenous cGMP on ICa can be mimicked by reducing cGMP hydrolysis through inhibition of PDE 5. A commonly used inhibitor of PDE 5 is zaprinast, which has been shown to be a specific inhibitor of this PDE isoform in the heart (Prigent et al., 1988; Kotera et al., 1998). Zaprinast has been shown to have an anti-adrenergic effect on ICa similar to exogenous cGMP (Ziolo et al., 2003). That is, zaprinast inhibited the ICa of cardiac myocytes following stimulation by isoproterenol or forskolin (see Figs. 23.1 and 23.2). The inhibitory effect of zaprinast was blocked by the PK-G inhibitor, KT5823 (see Fig. 23.2) and it was accompanied by an approximately threefold increase in intracellular cGMP levels and no change in cAMP levels. Since cAMP levels were not altered by zaprinast at the concentrations used in this study, significant non-specific inhibition of other PDE isoforms does not appear to occur with zaprinast at this concentration. These results also suggest that the effects of zaprinast were unlikely to be due to indirect effects of cGMP-induced decreases in cAMP levels caused by stimulation of PDE 2.

In standard whole-cell recording, in which intracellular Ca2+ concentration is unphysiologically low, zaprinast did not significantly alter basal (unstimulated) ICa. In contrast, zaprinast did inhibit basal ICa when the perforated-patch technique was used (which maintains a more physiological intracellular environment) or when whole-cell recording was used with free Ca2+ concentration maintained at a more physiological level (pCa = 7) (Ziolo et al., 2003). These results indicate that, under more physiological intracellular conditions, increases in endogenous cGMP can inhibit both the basal and cAMP-stimulated ICa via a mechanism that involves PK-G.

Intracellular Ca2+ modulates the activity of several isoforms of the enzymes that synthesize and hydrolyze cyclic nucleotides. As a result, the overall effects of the unphysiologically low levels of intracellular Ca2+ often used in standard whole-cell voltage clamp recording on modulation of ICa by different steps in the cAMP and/or cGMP pathways can be unpredictable. For example, perforated-patch recording enhances the ICa response to β-adrenergic stimulation, but reduces the ICa response to the non-specific PDE inhibitor IBMX (Kawamura and Wahler, 1994). Perhaps one reason that, with cGMP elevation, the basal response of ICa is typically small or non-existent while there is a much greater response of the cAMP-enhanced ICa, is that increased cAMP levels typically lead to an increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels, which then may upregulate one or more steps in the cGMP–PK-G pathway. As noted earlier, basal Ca2+ channel activity can be inhibited by PK-G under some circumstances (e.g. following overproduction of PK-G 1 in cardiac myocytes; Schröder et al., 2003) in which PK-G levels and/or activity are enhanced.

VI Compartmentalization of Cyclic Nucleotides

The cyclic nucleotide signaling pathways are known to demonstrate a substantial amount of compartmentation. For example, although both particulate and soluble G-cyclases synthesize cGMP, the two cyclases respond to different agonists (natriuretic peptides for the particulate enzyme and NO for the soluble one) and their responses are mediated by different effectors. Additionally, there are clearly localized microdomains in which synthesizing enzymes, PDEs and effectors are in close proximity and act as a functional unit. What has only recently begun to be appreciated is that the spatial distribution of components of the system is not always fixed (not solely due to physical constraints).

Some of the isoforms of the enzymes involved in synthesizing and degrading cyclic nucleotides are substrates for cyclic nucleotide-dependent kinases. Thus, cAMP exerts a negative feedback control of its own concentration and localization due to PK-A stimulation of PDE activity (Fischmeister et al., 2006). Similarly, PDE 5 (which is co-localized with soluble G-cyclase) is a substrate for PK-G and its activity is increased by PK-G phosphorylation. PK-G decreases the accumulation of soluble G-cyclase-generated cGMP by enhancing PDE 5 activity. On the other hand, PK-G increases the accumulation of particulate G-cyclase-generated cGMP by stimulating particulate G-cyclase activity. As a result, the distribution of cGMP within the cell is altered in response to PK-G activation. Additionally, when PDE activity is largely eliminated with a non-specific PDE inhibitor (IBMX), cGMP compartmentalization disappears and cGMP diffusion is no longer restricted, suggesting that cGMP diffusion within the cell is restricted primarily by the activity of PDEs, rather than by physical barriers (Castro et al., 2010).

Such regulation of cyclic nucleotide compartmentalization is not limited to feedback regulation of a cyclic nucleotide by its own effectors. That is, there is considerable cross-talk between the cAMP and cGMP systems. For example, the contractile response to β-adrenergic stimulation has been shown to be modulated by the soluble cGMP pool (i.e. the cGMP synthesized by soluble G-cyclase and degraded by PDE 5), but not the particulate cGMP pool, even though stimulation of particulate G-cyclase causes a larger global increase in cGMP levels than stimulation of soluble G-cyclase (Takimoto et al., 2007).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Ahmad Z, Green FJ, Subuhi HS, Watanabe AM. Autonomic regulation of type 1 protein phosphatase in cardiac muscle. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3859–3863.

2. Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases: structure, function and inhibition. Biochem J. 2001;357:593–615.

3. Armstrong D, Eckert R. Voltage-activated calcium channels that must be phosphorylation to respond to membrane depolarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84 2518–1522.

4. Bkaily G, Sperelakis N. Injection of protein kinase inhibitor into cultured heart cells blocks calcium slow channels. Am J Physiol. 1984;248:H745–H749.

5. Bkaily G, Sperelakis N. Injection of cyclic GMP into heart cells blocks the Ca2+ slow channels. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:H745–H749.

6. Castro LRV, Schittl J, Fischmeister R. Feedback control through cGMP-dependent protein kinase contributes to differential regulation and compartmentation of cGMP in rat cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2010;107:1232–1240.

7. duBell WH, Rogers TB. Protein phosphatase 1 and an opposing protein kinase regulate steady-state L-type Ca2+ current in mouse cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 2004;556:79–93.

8. Fischmeister R, Hartzell HC. Cyclic guanosine 3′,5′- monophosphate regulates the calcium current in single cells from frog ventricle. J Physiol. 1987;387:455–472.

9. Fischmeister R, Hartzell HC. Cyclic AMP phosphodiesterases and Ca2+ current regulation in cardiac cells. Life Sci. 1991;48:2365–2376.

10. Fischmeister R, Castro LRV, Abi-Gerges A, et al. Compartmentation of cyclic nucleotide signaling in the heart The role of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Circ Res. 2006;99:816–828.

11. Frace AM, Hartzell HC. Opposite effects of phosphatase inhibitors on L-type calcium and delayed rectifier currents in frog ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1993;472:305–326.

12. Francis SH, Busch JL, Corbin JD. cGMP-dependent protein kinases and cGMP phosphodiesterases in nitric oxide and cGMP action. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:525–563.

13. Goldberg ND, Haddox MK, Nicol SE, et al. Biological regulation through opposing influences of cyclic GMP and cyclic AMP: the Yin Yang hypothesis. Adv Cyclic Nucleotides. 1975;5:307–330.

14. Gupta RC, Neumann J, Watanabe AM, Lesch M, Sabbah HN. Evidence for presence and hormonal regulation of protein phosphatase inhibitor-1 in ventricular cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H1159–H1164.

15. Haddad GE, Sperelakis N, Bkaily G. Regulation of calcium channel by cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase in chick heart cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 1995;148:89–94.

16. Hartzell HC, Fischmeister R. Opposite effects of cyclic GMP and cyclic AMP on Ca2+ current in single heart cells. Nature. 1986;323:273–275.

17. Hescheler J, Kameyama M, Trautwein W, Mieskes G, Soling HD. Regulation of the cardiac calcium channel by protein phosphatases. Eur J Biochem. 1987;165:261–266.

18. Hescheler J, Mieskes G, Ruegg JC, Takai A, Trautwein W. Effects of a protein phosphatase inhibitor, okadaic acid, on membrane currents of isolated guinea-pig cardiac myocytes. Pflügers Arch. 1988;412:248–252.

19. Irisawa H, Kokubun S. Modulation of intracellular ATP and cyclic AMP of the slow inward current in isolated single ventricular cells of the guinea-pig. J Physiol. 1983;338:321–327.

20. Josephson I, Sperelakis N. 5′Guanylimidophosphate stimulation of slow Ca2+ current in myocardial cells. J Molec Cell Cardiol. 1978;10:1157–1166.

21. Kajimoto K, Hagiwara N, Kasanuki H, Hosoda S. Contribution of phosphodiesterase isozymes to the regulation of the L-type calcium current in human cardiac myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1549–1556.

22. Kameyama M, Hoffman F, Trautwein W. On the mechanism of β-adrenergic regulation of the Ca2+ channel in the guinea pig heart. Pflügers Arch. 1986;405:285–293.

23. Kawamura A, Wahler GM. Perforated-patch recording does not enhance effect of 3-isobutyl-l-methylxanthine on cardiac calcium current. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:C1619–C1627.

24. Klein G, Drexler H, Schröder F. Protein kinase G reverses all isoproterenol induced changes of cardiac L-type calcium channel gating. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;48:367–374.

25. Kohlhardt M, Haap K. 8-Bromo-guanosine-3′, 5′-monophosphate mimics the effect of acetylcholine on slow response action potential and contractile force in mammalian atrial myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1978;10:573–578.

26. Kontos HA, Wei EP. Hydroxyl radical-dependent inactivation of guanylate cyclase in cerebral arteries by methylene blue and LY83583. Stroke. 1993;24:427–433.

27. Kotera J, Fujishige K, Akatsuka H, et al. Novel alternative splice variants of cGMP-binding cGMP-specifc phosphodiesterase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26982–26990.

28. Levi RC, Alloatti G, Fischmeister R. Cyclic GMP regulates the Ca-channel current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Pflügers Arch. 1989;413:685–687.

29. Levi RC, AIloatti G, Penna C, Gallo MP. Guanylate cyclase-mediated inhibition of cardiac ICa, by carbachol and sodium nitroprusside. Pflügers Arch. 1994;426:419–426.

30. Lewis NP, Tsao PS, Rickenbacker PR, et al. Induction of nitric oxide synthase in human cardiac allograft is associated with contractile dysfunction of the left ventricle. Circulation. 1996;93:720–729.

31. Li T, Sperelakis N. Stimulation of slow action potentials in guinea pig papillary muscle cells by intracellular injection of cAMP, Gpp(NH)p, and cholera toxin. Circ Res. 1983;52:111–117.

32. Matsumoto S. Effect of molsidomine on basal Ca2+ current in rat cardiac cells. Life Sci. 1997;50:383–390.

33. Mehegan JP, Muir WW, Unverferth DV, Fertel RH, McGuirck SM. Electrophysiological effects of cyclic GMP on canine cardiac Purkinje fibers. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1985;7:30–35.

34. Mery PF, Lohmann SM, Walter U, Fischmeister R. Ca2+ current is regulated by cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase in mammalian cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1197–1201.

35. Mery PF, Pavoine C, Belhassen L, Pecker F, Fischmeister R. Nitric oxide regulates cardiac Ca2+ current Involvement of cGMP-inhibited and cGMP-stimulated phosphodiesterases through guanylyl cyclase activation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26286–26295.

36. Mubagwa K, Shirayama T, Moreau M, Pappano AJ. Effects of phosphodiesterase inhibitors and carbachol on the L-type calcium current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:H1353–H1363.

37. Nargeot J, Nerbonne JM, Engels J, Lester HA. Time course of the increase in myocardial slow inward current after a photochemically generated concentration jump of intracellular cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:2395–2399.

38. Nawrath H. Does cyclic GMP mediate the negative inotropic effect of acetylcholine in the heart?. Nature. 1977;267:72–74.

39. Ono K, Trautwein W. Potentiation by cyclic GMP of β-adrenergic effect on Ca2+ current in guinea-pig ventricular cells. J Physiol. 1991;443:387–404.

40. Osterreider W, Brum G, Hescheler J, et al. Injection of subunits of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase into cardiac myocytes modulates Ca2+ current. Nature. 1982;298:576–578.

41. Paulus WJ, Kastner S, Pujadas P, et al. Left ventricular contractile effects of inducible nitric oxide synthase in the human allograft. Circulation. 1997;96:3336–3342.

42. Pyo R, Wahler GM. Ventricular myocytes isolated from rejecting cardiac allografts exhibit a reduced β-adrenergic contractile response. J Molec Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:773–776.

43. Prigent AF, Fougier S, Nemoz G, et al. Comparison of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase isozymes from rat heart and bovine aorta Separation and inhibition by selective reference phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:3671–3681.

44. Reuter H, Stevens C-F, Tsien RW, Yellen G. Properties of single calcium channels in cardiac cell culture. Nature. 1982;297:501–504.

45. Rivet-Bastide M, Vandecasteele G, Hatem S, et al. cGMP-stimulated cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase regulates the basal calcium current in human atrial myocytes. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2710–2718.

46. Rozanski GJ, Witt RC. IL-1 inhibits β-adrenergic control of cardiac calcium current: role of L-arginine/nitric oxide pathway. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H1753–H1758.

47. Schröder F, Klein G, Fiedler B, et al. Single L-type Ca2+ channel regulation by cGMP-dependent protein kinase type 1 in adult cardiomyocytes from PKG 1 transgenic mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:268–277.

48. Schulz R, Nava E, Moncada S. Induction and potential biological relevance of a Ca2+-independent nitric oxide synthase in the myocardium. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;105:575–580.

49. Shigenobu K, Sperelakis N. Ca2+ current channels induced by catecholamines in chick embryonic hearts whose fast Na+ channels are blocked by tetrodotoxin or elevated K+. Circ Res. 1972;31:932–952.

50. Stojanovic MO, Ziolo MT, Wahler GM, Wolska BM. Anti-adrenergic effects of nitric oxide donor SIN-1 in rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:C342–C349.

51. Sumii K, Sperelakis N. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase regulation of the L-type calcium current in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1995;77:803–812.

52. Takimoto E, Belardi D, Tocchetti CG, et al. Compartmentalization of cardiac β-adrenergic inotropy modulation by phosphodiesterase type 5. Circulation. 2007;115:2159–2167.

53. Tandan S, Wang Y, Wang TT, et al. Physical and functional interaction between calcineurin and the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel. Circ Res. 2009;150:51–60.

54. Thakkar J, Tang SB, Sperelakis N, Wahler GM. Inhibition of cardiac slow action potentials by 8-bromo-cyclic GMP occurs independent of changes in cyclic AMP levels. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1989;66:1092–1095.

55. Tohse N, Sperelakis N. Cyclic GMP inhibits the activity of single calcium channels in embryonic chick heart cells. Circ Res. 1991;69:325–331.

56. Tsien RW, Giles W, Greengard P. Cyclic AMP mediates the action of adrenaline on the action potential plateau of cardiac Purkinje fibers. Nature. 1972;240:181–183.

57. Verde I, Vandecasteele G, Lezoualc’h F, Fischmeister R. Characterization of the cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase subtypes involved in the regulation of the L-type Ca2+ current in rat ventricular myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:65–74.

58. Vogel S, Sperelakis N. Induction of slow action potentials by microiontophoresis of cyclic AMP into heart cells. J Molec Cell Cardiol. 1981;13:51–64.

59. Wahler GM, Dollinger SJ. Nitric oxide donor SIN-1 inhibits mammalian cardiac calcium current through cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C45–C54.

60. Wahler GM, Sperelakis N. Intracellular injection of cyclic GMP depresses cardiac slow action potentials. J Cyclic Nucleotide Protein Phosphorylation Res. 1985;10:83–95.

61. Wahler GM, Sperelakis N. Cholinergic attenuation of the electrophysiological effects of forskolin. J Cyclic Nucleotide Protein Phosphorylation Res. 1986;11:1–10.

62. Wahler GM, Rusch NJ, Sperelakis N. 8-Bromo-cyclic GMP inhibits the calcium channel current in embryonic chick ventricular myocytes. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1990;68:531–534.

63. Wegener JW, Nawrath H, Wolfsgruber W, et al. cGMP-dependent protein kinase I mediates the negative inotropic effect of cGMP in the murine myocardium. Circ Res. 2002;90:18–20.

64. Xie Q, Nathan C. The high-output nitric oxide pathway: role and regulation. J Leukocyte Biol. 1994;56:572–582.

65. Yang X, Chowdhury N, Cai B, et al. Induction of myocardial nitric oxide synthase by cardiac allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:714–721.

66. Yang L, Liu G, Zakharov SI, et al. Protein kinase G phosphorylates Cav1.2 alpha1c and beta2 subunits. Circ Res. 2007;101:465–474.

67. Ziolo MT, Dollinger SJ, Wahler GM. Myocytes isolated from rejecting transplanted hearts exhibit reduced basal shortening which is reversible by aminoguanidine. J Molec Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:1009–1017.

68. Ziolo MT, Harshbarger CH, Roycroft KE, et al. Myocytes isolated from rejecting transplanted rat hearts exhibit a nitric oxide-mediated reduction in the calcium current. J Molec Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1691–1699.

69. Ziolo MT, Lewandowski SJ, Smith JM, Romano FD, Wahler GM. Inhibition of cyclic GMP hydrolysis with zaprinast reduces basal and cyclic AMP-elevated L-type calcium current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:986–994.