Chapter 46

Contraction of Muscles

Mechanochemistry

Chapter Outline

III. The Mechanisms of Force Production and Shortening: Muscle Mechanics

IIIA. Steady-State Relations Between Force and Length and the Sliding-Filament Theory

IIIB. The Structure of Muscle: Interdigitating Filament Systems

IIID. Relationships among Force, Velocity, Work and Energy Utilization

IIIF. Transient Mechanical Behavior and the Cross-Bridge Cycle

VI. Comparative Mechanochemical Function

I Summary

This chapter focuses largely on muscle structure in relation to muscle mechanics and energetics and relevance to different muscle types. Striated muscle structure is first developed as a paradigm in conjunction with mechanics, leading to the formulation of the sliding-filament theory. Muscle contractility continues with further characterization of the relationships among force, velocity, work and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) utilization. The mechanism at the molecular level, i.e. the cross-bridge cycle, is similarly developed, matching structural and biochemical knowledge with transient mechanical studies. An investigation of the energy requirements in terms of ATP hydrolysis of the cross-bridge cycle is then followed by a discussion of muscle metabolism and the route for synthesis of the ATP necessary for contractile activity. The chapter then shifts from considerations of muscle in general to comparative muscle physiology and behavior of different fiber types. In particular, smooth muscle is treated in detail and its regulation, mechanical properties and energetics are considered and contrasted to those of striated muscle.

II Introduction

The generation of force and movement by muscle is an area of physiology and biophysics that has fascinated scientist and layman alike since the dawn of scientific inquiry and reverberates strongly in today’s nanomachine quest (Huang and Juluri, 2008). The history of the study of muscle is elegantly chronicled by Dorothy Needham in Machina Carnis (1971). Because of its highly organized and repeating structure, skeletal muscle has proven more amenable to structural analysis (such as x-ray diffraction) than most biological tissues. Thus, it has served as a paradigm for unraveling relationships between function and structure. This has become particularly exciting in conjunction with the techniques of molecular biology, which offer the potential for altering particular amino acids and molecular measurements with manipulators, such as laser tweezers. These tools offer the potential for directly testing the links between structure at nanometer resolution and function. The focus of this chapter is on the nature of the muscle mechanics and mechanochemical energy conversion. Muscle is one of the most efficient energy converters known and studies in this area couple classical enzyme kinetics, muscle mechanics and cross-bridge theories (Barclay et al., 2010).

The major focus of this chapter is on the molecular and cellular levels which form the basis understanding muscle contraction for organ and whole organism function, such as sports medicine and kinestheology. Muscle mechanochemistry at the cellular level also has major consequences at the organ and whole-animal levels. Skeletal muscle constitutes approximately 40% of human body mass. If we include cardiac and smooth muscle, the total muscle mass reaches the 50% level. One consequence of this is that approximately 30% of basal metabolism is related to muscle and as much as 90% of a person’s total metabolism during strenuous exercise can be related to meeting the energy requirements of muscle. This chemical activity can in turn produce a significant heat load for the organism. Other functions that are associated with the large muscle mass are the storage and mobilization of metabolites (primarily glucose and amino acids). Also, there are significant consequences to alterations in muscle electrolyte metabolism, since it is a major storage site for ions such as H+, Cl− and Mg2+. Some of these ramifications are presented as related to molecular processes in muscle.

Our study of the muscle contraction first involves investigation of mechanisms underlying the generation of macroscopic force and shortening. We first consider how force is developed and how the mechanical behavior of muscle is quantitated, a field known collectively as muscle mechanics. This is then integrated with the current picture of muscle structure as a first step in constructing theories of muscle function. Next, we consider muscle energetics, governed by thermodynamic rules for energy conversion and the constraints they place on models proposed for muscle contraction. We relate energetics and mechanics to the kinetics of the myosin ATPase as a basis for cross-bridge cycling mechanisms. Muscle metabolism and the matching of ATP demand with ATP synthesis will complete the picture of mechanochemical energy conversion.

The second major area involves study of the mechanisms underlying the regulation of muscle contraction. The control of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, a key intracellular messenger, forms an area of study known as excitation–contraction coupling. The intracellular receptors transducing the Ca2+ signal reflect the great diversity of types of muscle that have evolved in response to a wide variety of functional needs. These muscles also have much in common. All muscle contains the proteins actin and myosin, which are the locus of the mechanochemical energy conversion. Chemical energy in the form of ATP hydrolysis is the immediate driving reaction for all muscle energy transduction. Another feature common to all muscle types is that calcium ions, at micromolar concentrations, are the primary second messenger in the regulatory mechanisms. We first focus on these common aspects, using a generalized striated muscle as the model. Then with an understanding of these common mechanisms, we consider the different muscle types.

III The Mechanisms of Force Production and Shortening: Muscle Mechanics

Studies of the mechanical behavior of muscle have played a central role in our understanding of muscle and have also formed an integral part of the language of muscle physiology (Hill, 1965). These studies before the late 1950s were primarily phenomenological, though they were also important in characterization of muscle performance. Such studies remain important in characterization of muscle myopathies and in current mechanistic studies, e.g. in describing the functional consequences of changing muscle protein isoforms in transgenic animals.

There are two arbitrary but natural divisions in studies of muscle mechanics. The first division involves steady-state relationships in which force and velocity are constant in time. This information was crucial to the development of the three-component model of muscle contraction (see below), a model still valid for whole muscle behavior (Jewell and Wilkie, 1958). Such studies also provided one pillar supporting the sliding-filament theory and were extensively investigated in the 1960s (Gordon et al., 1966).

Studies of mechanical transients form a second division. They assumed a more central importance during the early 1970s (Huxley and Simmons, 1971) with the growing realization that information at the level of individual cross-bridges could be gained from mechanical studies on single fibers. These studies of muscle responses to rapid changes in mechanical constraints are even more valuable to unraveling cross-bridge behavior when coupled with recently improved temporal resolution of x-ray diffraction of muscle (Huxley, 2004; Squire and Knupp, 2005).

IIIA Steady-State Relations Between Force and Length and the Sliding-Filament Theory

A first step in muscle mechanics involves a description of muscle behavior in terms of relationships between the mechanical variables of force and length. Apparatus for transduction and recording of these variables has evolved considerably over this century, but the historical apparatus is still responsible for much of the language of muscle physiology. Since it was easier to control force than length, by hanging a fixed weight on the muscle, terms such as preload and afterload entered the vocabulary (see later section on force–velocity relationships). However, in view of what is now known about structure, it is conceptually easier to use length as the independent variable.

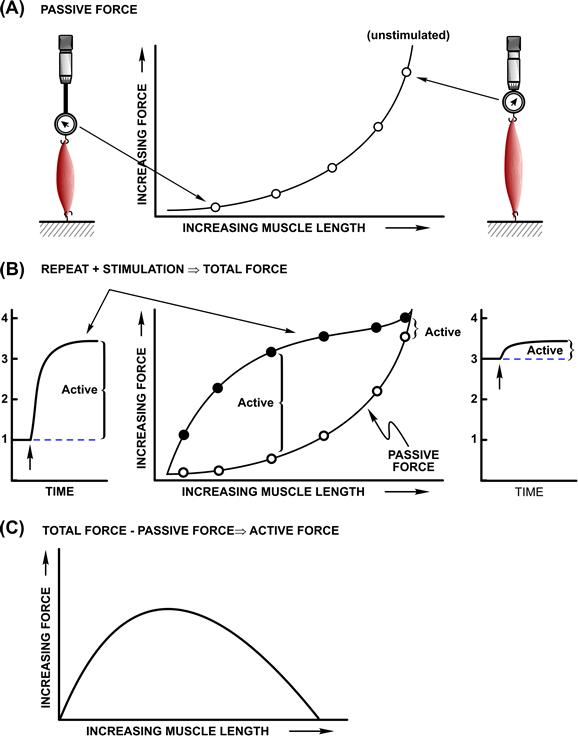

Figure 46.1 shows a schematic of an experimental apparatus for measurement of muscle force–length relationships. In this setup, length is the controlled variable and the steady-state force at various lengths is measured. In developing these relationships, we consider the performance of an isolated muscle, or single muscle cell known as a muscle fiber. After mounting in the apparatus, muscle length is adjusted to a specific length then set isometric (fixed total length) and the steady-state force is measured. The relationship between the unstimulated force (often designated as passive force) and muscle length is designated the passive length–tension relationship. This relationship can be characterized as an exponential spring, F = A1 + A2 exp(A3X), whose behavior is similar to that of a rubber band with its stiffness increasing with length. This relationship can also show a dependence on the direction of the imposed length changes, known as hysteresis, but deviations are small in a true steady state. Some form of passive force is common to all muscles, but an exact anatomical assignment of the structures underlying passive force is dependent on both the type of muscle and the preparation studied.

FIGURE 46.1 Measurement and operational definitions of muscle force–length relationships. (A) Relation between isometric force under unstimulated conditions, passive force and muscle length. (B) Relation between isometric force and length under stimulated conditions, total force. (C) Active force operationally defined as the difference between total force and passive force is shown as a function of muscle length.

The next stage of this analysis involves a similar protocol but includes stimulation of the muscle to characterize the parameters associated with activated muscle. With active muscle, the language that evolved reflected the state of understanding and the experimental apparatus. The response to a single electrical shock is known as a twitch contraction. At one time, this was believed to be some form of elemental or quantal behavior of muscle, hence its historical importance. Increasing the frequency of stimulation leads to a summation in time of the individual twitch responses, known as temporal summation. Beyond a certain frequency (depending on muscle type and temperature), the force response becomes a smooth, fused curve, called an isometric tetanus. These responses to stimulation are ultimately related to the Ca2+ handling underlying activation of the contractile proteins. For our present purposes, we consider only isometric tetani, so that the mechanical behavior of the fully activated contractile apparatus can be considered, without complications arising from behavior attributable to non-steady-state Ca2+ signaling.

Tetanic stimulation adds an additional increment of force to the passive force present at a given length. The passive force plus active (stimulated) force measured as a function of muscle length is shown in Fig. 46.1. This relationship is known as the total force–length curve. The total force–length relationship varies considerably from muscle to muscle, though the component passive and active force–length relationships for skeletal muscles are qualitatively similar. The differences are largely ascribable to the relative amount of passive force developed at the length at which active force is optimal.

For a structure–function mechanism, the relationship between the additional active force generated when a muscle is stimulated and muscle length is paramount. The active force–length relationship is calculated by subtracting the passive force relation from that for total force. The active force–length curve is unusual in that it decreases to zero at both long and short muscle lengths. For most materials, including polymers like rubber, force increases as length is increased. This typical behavior is also seen for the passive force as shown in Fig. 46.1. The observation that active force decreased at long muscle lengths was critical to eliminating theories that involved folding of continuous muscle filaments as the basis for the generation of force upon activation. To understand the relationship between active force and muscle length, it is necessary to consider muscle structure.

IIIB The Structure of Muscle: Interdigitating Filament Systems

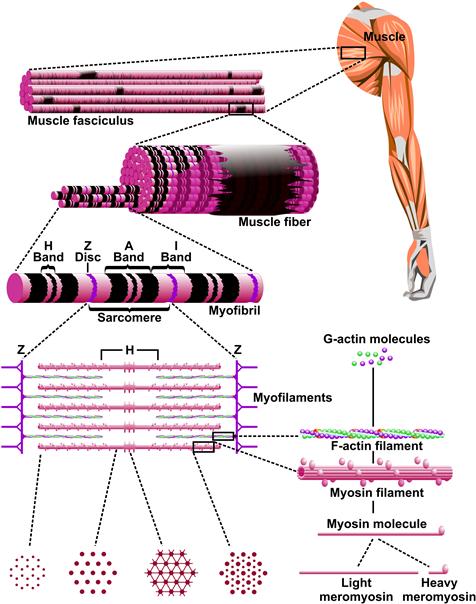

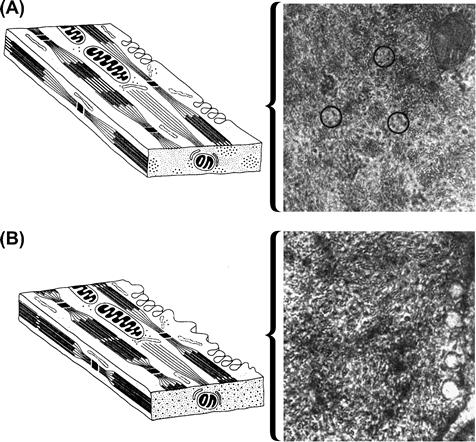

Muscle cells are composed of a filament system underlying their mechanical properties and internal membrane systems related to control of contraction. The filament structure repeats on both the transverse and longitudinal directions as shown in Fig. 46.2. A muscle fiber is composed of myofibrils whose fundamental longitudinal repeating unit is the sarcomere. The sarcomere consists of two interdigitating filament systems, thick (14 nm) myosin-containing filaments and thin (7 nm) actin-containing filaments which underlie the banding pattern seen under optical microscopy and the moniker, striated or striped muscle. The optical properties of the sarcomere due to the overlapping filaments gave rise to the nomenclature for the banding regions. The I-band contains only thin filaments and is optically isotropic, whereas the A-band contains both filament types and is anisotropic. The constancy of A-band dimensions, independent of total muscle length (Huxley amd Niedergerke, 1954), was a key experimental finding, leading to the concept that filament length was constant. Constant filament lengths and interdigitating filaments are best observed at the electron microscope level (Fig. 46.3), where interpretation of the changing banding pattern with muscle length was first elucidated (Huxley, 1953).

FIGURE 46.2 Skeletal muscle structure. The whole muscle is constructed of fundamental repeating units. A muscle cell or fiber is composed of myofibrils whose fundamental repeating unit is the sarcomere. All views are longitudinal except the cross-sections of the sarcomere (G, H, I).

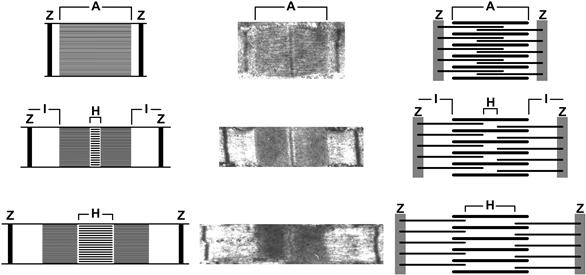

FIGURE 46.3 Electron micrographs and diagrams of sarcomeres at various muscle lengths. The sliding-filament theory is based on the constant length of the thick and thin filaments. Under light microscopy, this leads to the constancy of A-bands (containing both thick and thin filaments, anisotropic, A), while I-bands (containing only thin filaments, isotropic, I). Other designations from light microscopy are the Z-band (Z) and H-zone (H).

IIIC Sliding-Filament Theory

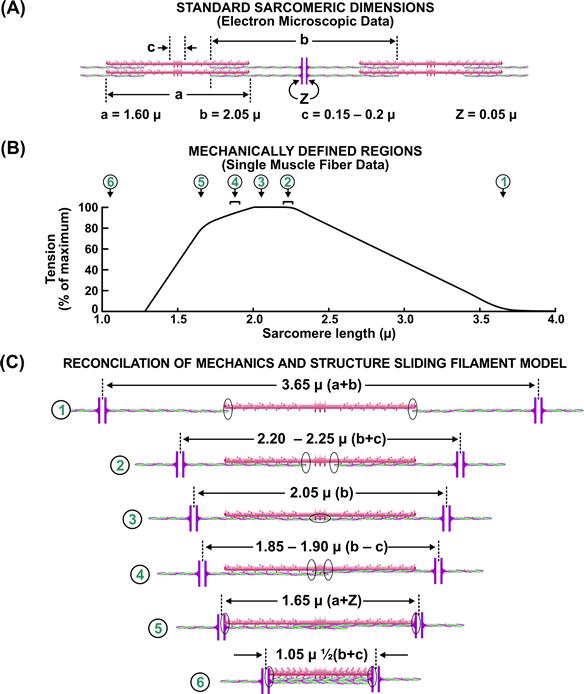

Based on this structure, the sliding-filament theory explains the active–force relationship in terms of active force being proportional to the overlap between thick and thin filaments of constant length, which are free to interdigitate and slide past one another. This mechanical correlate of the proposed sliding-filament structure was tested in the classic work of Gordon et al. (1966) and is summarized in Fig. 46.4. The clearest correlation between the level of active isometric force and extent of filament overlap is in the region of decreasing force between sarcomere lengths of 2.2 and 3.6 μm, i.e. the descending limb of the active force–length curve. The interpretation of the ascending limb of the force–length relation (e.g. 1.2–2.2 μm) is not as straightforward. This is of particular interest for cardiac muscle which normally operates in the ascending limb. Changes in activation, Ca2+-sensitivity and cooperatively of myosin–actin interaction at short lengths have been proposed to explain the ascending limb in cardiac muscle. The loss of force at these lengths can also be attributed to double filament overlap and compression of the contractile elements while interdigitating. Recent interest in structure–function analysis involves the sarcomeric giant protein nebulin (MW 700–900 kDa). Experiments with knockout mice indicate that nebulin plays a critical role in setting the length of the thin filament. One consequence is the length–tension is shifted leftward and maximum force is reduced. This appears to be an important contributor to muscle weakness in patients with nemaline myopathy (Ottenheeeijm and Granzier, 2010). The sliding-filament theory is widely accepted, but the basis of force generation remains an active area of research (see Section IIIE on cross-bridge theory).

FIGURE 46.4 Structural basis for the active isometric force-length relationship. (Modified from Gordon et al., 1966.)

IIID Relationships among Force, Velocity, Work and Energy Utilization

Together with the relationship between force and length, the relationship between force and shortening velocity and the derived work and power are fundamental to characterizing muscle performance. With current technology, one would mechanically impose a constant velocity or force and measure the other as a function of time. Measurements would be carried out under tetanic conditions to eliminate transients during activation and are limited to the plateau region of the force–length relation to avoid any length dependence.

It is of more than just historical interests to consider the apparatus used more than 70 years ago, as the nomenclature prevalent in muscle physiology today, particularly in the language of cardiac physiology, reflects these early measurement protocols.

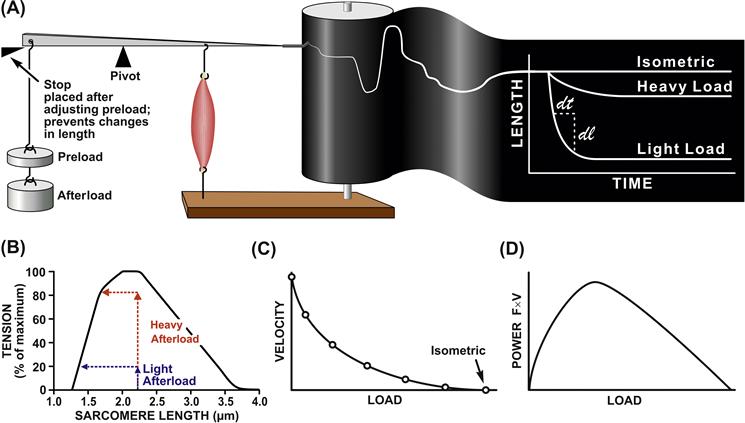

Figure 46.5A depicts the experimental apparatus used for measurement of force–velocity relations. Using the lever system, a preload is placed on the unstimulated muscle. Because the muscle is unconstrained, it stretches to the length at which the preload matches the force on the passive force–length relation. Then a mechanical stop is placed so that no further increases in length can occur. The importance of the preload is that it determines the initial length of the muscle and, consequently, the maximum force possible, in keeping with the active force–length relation. Then a mechanical stop is placed so that no further increases in length can occur. Additional loads now can be placed on the apparatus without changing muscle length. The total load is known as the afterload. The name “afterload” derives from the fact that the muscle does not “see” this load, as it is borne by the stop, until “after” it is stimulated. The muscle is then stimulated and when the muscle generates an isometric force just greater than the afterload, the muscle shortens, as indicated in tracing on the drum and shown on the unrolled drum paper in the right panel of Fig. 46.5. During the initial moments after shortening begins, there is a steady rate of shortening (often extrapolated), which subsequently declines and stops as the muscle reaches its final shortened length. This length will correspond to that point in the active force–length curve corresponding to the afterload. Another way of visualizing “why shortening stops” can be seen in Fig. 46.5, in which the route of contraction can be shown against the force–length relation. As the muscle shortens, the afterload becomes isometric at a shorter length where, according to its force–length relation, the muscle can only generate force equal to that of the afterload. This is where shortening stops. Both the distance shortened and the velocity can be seen to be dependent on the afterload. In Fig. 46.5C, the relation between shortening velocity and afterload is plotted. The interesting feature is that this relationship is hyperbolic with the velocity decreases rapidly as the afterload is increased. Several equations have been proposed to fit these data, however, the one most widely used is an equation attributed to A.V. Hill, which is expressed as:

(46.1)

(46.1)

where a and b are constants, Fo is the isometric force and Vmax is the unloaded shortening velocity. a/Fo = b· Vmax are dimensionless constants that determine the curvilinearity of the Hill equation and are equal to ≈0.3 for skeletal muscle. The mechanistic origin of this parameter is controversial. Although low values are often associated with efficient muscle performance, a generally accepted theoretical basis remains to be found. The parameter a was initially proposed by Hill to be related to a heat measurement, called the shortening heat, tying energetics to mechanics, but this was shown not to be constant. Although many other equations have been proposed, the scientific stature and an apparent link between heat and mechanical measurements led to the dominance of the Hill equation in the literature.

FIGURE 46.5 Relations between afterload and velocity, extent of shortening, and power generated by muscle. (A) Historical “Afterload Contraction” apparatus (left panel) and length tracing vs time (right panel). (B) Afterload contraction trajectory plotted on a length–tension plot. Muscle force–length relation is superimposed, showing its limitation on the extent of muscle shortening. (C) Velocity vs afterload relation. (D) Power (= load×velocity) vs Afterload relation.

The power output of muscle, which is the product of afterload times velocity, can be calculated from the relation between afterload and velocity. A consequence of the hyperbolic nature of the Hill equation is that the power output of muscle shows a relatively broad range around a maximum. An advantage of the Hill formulation over others is that it is symmetrical. This can be seen best in its normalized form:

(46.2)

(46.2)

where  is the normalized force (F/Fo),

is the normalized force (F/Fo),  is normalized velocity (V/Vmax)s and

is normalized velocity (V/Vmax)s and  = a/Fo = b/Vmax. As power is given by the product of force times velocity, Equation 46.1 or 46.2 can be readily used to derive a relationship between power and load or velocity. The optimal load or velocity for maximum power output can also be derived from these equations and is equal to

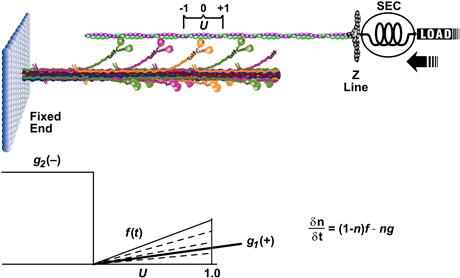

= a/Fo = b/Vmax. As power is given by the product of force times velocity, Equation 46.1 or 46.2 can be readily used to derive a relationship between power and load or velocity. The optimal load or velocity for maximum power output can also be derived from these equations and is equal to  ; for skeletal muscle this equals about 0.3 times the maximum load or velocity. These equations are useful in the design of ergonometric devices to optimize performance. The molecular basis for the force–velocity relation is not clear and many hypotheses have been put forth. The widely known of these models is the kinetic scheme of A.F. Huxley (1957). In this model, rate constants for cross-bridge formation/breakage are functions of position. This model (Fig. 46.6) can explain the relationship between force and velocity, but it is not adequate for the transient behavior as those seen (see Fig. 46.10) when rapid step changes are imposed (see Section IIIF on tension transients). While it is relatively easy to envision the “geometric limits” imposed by the sliding-filament model which underlie the force–length relation, especially at long sarcomere lengths (see Fig. 46.4), it is not as easy to visualize the “kinetic constraints” which underlie the force–velocity relation. Simplistically, one possible view is that the probability of making a force generating attachment of a myosin head to an actin is lower when the thick and thin filaments are moving relative to one another.

; for skeletal muscle this equals about 0.3 times the maximum load or velocity. These equations are useful in the design of ergonometric devices to optimize performance. The molecular basis for the force–velocity relation is not clear and many hypotheses have been put forth. The widely known of these models is the kinetic scheme of A.F. Huxley (1957). In this model, rate constants for cross-bridge formation/breakage are functions of position. This model (Fig. 46.6) can explain the relationship between force and velocity, but it is not adequate for the transient behavior as those seen (see Fig. 46.10) when rapid step changes are imposed (see Section IIIF on tension transients). While it is relatively easy to envision the “geometric limits” imposed by the sliding-filament model which underlie the force–length relation, especially at long sarcomere lengths (see Fig. 46.4), it is not as easy to visualize the “kinetic constraints” which underlie the force–velocity relation. Simplistically, one possible view is that the probability of making a force generating attachment of a myosin head to an actin is lower when the thick and thin filaments are moving relative to one another.

FIGURE 46.6 Schematic representing a two-element model of muscle and Huxley’s (1957) mathematical model. Top: Half-sarcomere containing a myosin thick filament and actin-containing thin filament, which constitutes a contractile component, coupled in series with an elastic component (SEC). Bottom left: functional form of rate constants for cross-bridge attachment (f) and detachment (g1 and g2) as a function of U, the cross-bridge position coordinate shown at top. Bottom, right: differential equation describing the change in number of cross-bridges. Force generated in this model is equal to the number of attached cross-bridges, n, times the force of an individual cross-bridge.

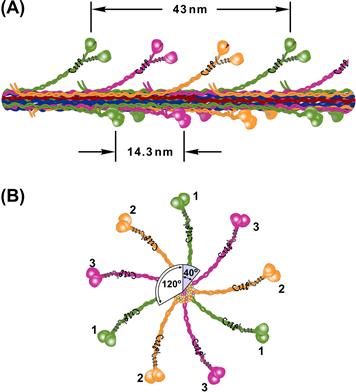

IIIE Cross-Bridge Theory

The most prevalent theory for force generation involves the concept of cyclic interactions between the heads of myosin molecules (cross-bridges) projecting from the thick filaments and the actin molecules comprising the thin filaments. Evidence from electron micrographs indicates that these cross-bridges, in various conformations, bridge the gap between thick and thin filaments. Based on both micrographs and x-ray diffraction data, these projections occur at intervals of 14.3 nm. The best evidence (from mass comparisons) is that three myosin molecules are located at each site, with an identical repeat at about 43 nm. The structure of the thick filament is shown in Fig. 46.7.

FIGURE 46.7 Rendition of the myosin thick-filament structure based on current evidence. (A) Longitudinal view showing three myosin molecules per site rotated from one another by 120°. Cross-bridge sites occur every 14.3 nm, but are rotated by 40° with respect to the previous site, so that an identical repeat occurs every 43 nm. (B) End view of the filament showing three superimposed color-coded sites.

The evidence for cyclic interaction is partly based on structural considerations. Striated muscle can generate force and shorten over a range of about 50–150% of its rest length. Since a muscle is composed of identical sarcomeres, each sarcomere operates over the same range. For a sarcomere of 2.2 μm, this operating range would be about 1.1–3.3 μm. Since the thin filaments of each half of the sarcomere move toward the center, a sarcomere shortening from 3.3 to 1.1 μm (Δ of 2.2 μm) would require a movement of thin filaments on each side of the sarcomere of one half that distance or 1.1 μm relative to the thick filament. This distance is considerably longer than the cross-bridge spacing (0.014 μm) and is, in fact, longer than a single myosin molecule (0.150 μm). So, it is not possible for a myosin cross-bridge to remain attached to actin in a structure with interdigitating filaments of constant length and relative sliding of more than 1 μm. Hence some form of cyclic interactions between myosin cross-bridges and actin is required to permit the observed relative filament movement. For example, if a cross-bridge can attach over a working range of 10 nm, than 100 repeated cycles of attachment/detachment would be required for a relative filament movement of 1 μm.

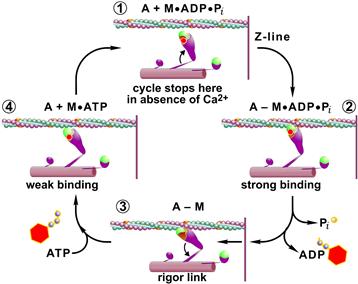

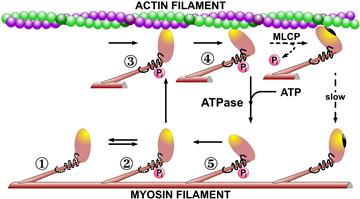

A second basis for the cross-bridge theory arises from biochemical studies on isolated muscle proteins. The myosin molecule consists of a long rod-like region important for assembly into thick filaments and a globular head region, which contains the ATPase activity. The globular head, or S1 region (see Fig. 46.7), has dimensions consistent with the projections identified as cross-bridges in electron micrographs. Studies of the kinetics of ATP hydrolysis by myosin, involving stopped-flow apparatus and other techniques for the measurement of rapid time courses, have provided a framework for cyclic interaction of the S1 myosin head with actin. The kinetic scheme is shown in Fig. 46.8. The physiological ATPase activity (known as Mg2+-ATPase activity) of purified myosin is relatively low, but, importantly, it is activated 200-fold by actin, the principal protein of the thin filament. In the absence of ATP, purified actin and myosin bind strongly. In intact muscle, this is the cause for the stiffness of muscle in the absence of nucleotide associated with “rigor”. Addition of ATP to a “rigor complex” of actin and myosin dissociates the complex by producing a weak binding state, because the binding of ATP to myosin weakens the binding to actin (see Fig. 46.8, steps 3 to 4). ATP hydrolysis by myosin alters the binding characteristics and cross-bridge orientation (step 4 to 1), leading to a strong binding state (step 1 to 2). The biochemical cycle is completed as the products of ATP hydrolysis, first inorganic phosphate (Pi) and then ADP, dissociate from the myosin head. One ATP molecule is hydrolyzed per cross-bridge cycle. The structural details of this cycle have recently been significantly upgraded due to the high resolution x-ray diffraction data of the myosin head (Rayment et al., 1996) and of single muscle fibers (Lombardi et al., 2004). As shown in the insets in Fig. 46.8, these data suggest that binding of ATP to myosin alters the conformation of the myosin head and consequently its binding to actin. Correlating this cross-bridge cycle based on biochemical data with mechanical steps in force generation is a major focus of muscle physiology. One approach involves the study of rapid mechanical transients.

FIGURE 46.8 The cross-bridge cycle. Schematic of the combination of information from muscle mechanics and biochemical kinetics of the actin activated myosin ATPase (see text for details).

IIIF Transient Mechanical Behavior and the Cross-Bridge Cycle

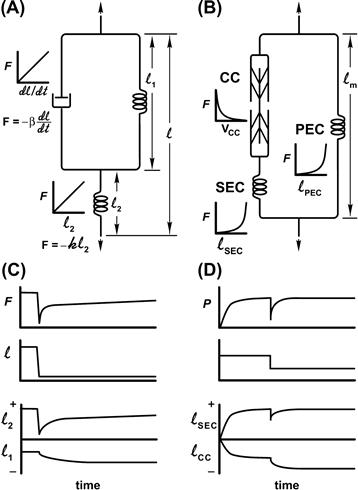

Analysis of the mechanical properties of any material generally involves the imposition of known mechanical perturbations (e.g. step or sinusoidal changes in length or force; called strain) while recording the force (stress) response of the system. When modeling the time course of the response, combination of two types of components (spring-like and viscous elements) can account for the behavior of most materials. The behavior of spring-like material is characterized by an instantaneous relationship between force and length, whereas for a viscous element, a resistive force is proportional to the rate of imposed length change. Combination of these elements can approximate the behavior of many materials (Fig. 46.9).

FIGURE 46.9 Models forming the basis of classic analysis of muscle mechanics. (A) Three-element Voight model containing two linear spring elements (l1 and l2) combined with a “dashpot”, a linear viscous element. (B) Three-element model of muscle containing a contractile component (CC), a parallel elastic component (PEC) and a series elastic component (SEC). Graphs indicate the behavior of each element. (C) Time course of the response of the Voight model and its individual components to imposition of a rapid step change in length. (D) Similar responses of the muscle model to a rapid step change (note that the initial muscle length here is chosen such that the PEC does not play a role in this response).

Using this type of analysis, the steady-state behavior of muscle has long been adequately described by two parallel elements: a spring-like element, representing the passive force–length characteristics and a contractile element representing the characteristics an activated muscle (Hill, 1938). For our generalized skeletal muscle at Lo, a length of optimal filament overlap, little parallel passive force exists. Thus, the behavior we are describing is that of the contractile component alone. Imposition of a rapid step shortening leads to a rapid drop in active force, followed by a redevelopment of tension. This suggests that muscle behavior can be modeled by two elements linked in series (see Fig. 46.9). This model consists of a series elastic spring, which instantaneously responds to the imposed length change and a contractile component, whose behavior is described by the Hill equation, a non-linear, viscous like relationship between force and velocity. For this model, step changes in force yield a rapid, in-phase shortening, attributable to the series elastic spring followed by a slower shortening phase, attributable to the contractile component. This model can explain some aspects of transient mechanical behavior and was the first to be used to associate anatomical elements with model elements. The anatomical site associated with the series elastic component (SEC) has evolved and has considerably altered our view of muscle mechanics.

The SEC can be characterized in terms of the extent of shortening required to discharge the maximal isometric force (Fo). Studies on intact, whole muscle suggested that a change in the length of muscle of 2–3% Lo was sufficient transiently to reduce active force to zero (Jewell and Wilkie, 1958). This elasticity can be attributed to connective elements, such as tendons and similar passive structures, as well as any elasticity in the apparatus used to measure force. A 2–3% change in Lo can be translated to a relative filament motion of 20–30 nm, i.e. 40–60 nm for a 2.2 μm sarcomere. This is significantly larger than the cross-bridge spacing (14.3 nm), reinforcing the concept that such behavior is external to the contractile component and in series with cross-bridges. The two-component model is phenomenologically useful and it can predict behavior of many whole tissues, particularly those with large intrinsic SEC, such as some smooth muscle. However, as improvements in the temporal resolution of mechanical measurements advanced, this model was found to be inadequate for the behavior of single skeletal muscle fibers.

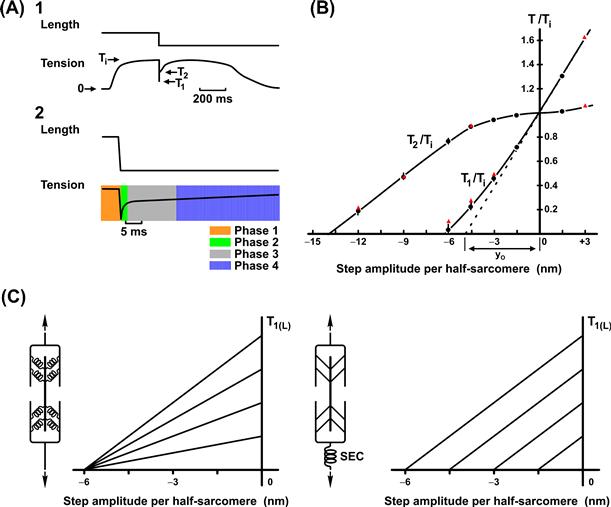

In the 1970s, techniques for imposition of step changes greatly improved as devices to impose length changes, transducers and recording apparatus achieved millisecond resolution. At the same time, techniques for working with single muscle fibers and “spot follower” devices for control of sarcomere length, rather than overall muscle length, were developed. These new measurements indicated that the true SEC extent was much smaller than that previously measured in whole muscle. (Previous measurements apparently also included an artifact of the slow response time of the recording system.) Current estimates of the SEC for striated muscle are less than 0.5% Lo, approximately 6 nm per half-sarcomere, clearly in a range to be potentially associated with cross-bridges themselves. Moreover, the time courses of responses (Fig. 46.10) were not consistent with an instantaneous spring connected in series with a contractile element, which also was characterized by an instantaneous force–velocity relationship.

FIGURE 46.10 Huxley–Simmons (1971) experiments. (A) Transient force responses to very rapid (<1 ms) step changes in length, which led to revision of classical muscle mechanics. (B) Dependence of phase 1 and phase 2 force amplitudes on muscle length. (C) Dependence of T1 if the series elasticity resided within the cross-bridge itself (left) and if the series elasticity was located in a classic SEC (right). Huxley and Simmons data support in the model shown in the left panel of panel of (C).

Huxley and Simmons (1971) provided the first evidence that an instantaneous spring-like behavior could be attributed to the cross-bridges themselves. They exploited the fact that the number of cross-bridges could be varied by taking advantage of the force–length relationship. As shown in Fig. 46.10, if the SEC is intrinsic to the cross-bridge, then the magnitude of the shortening step required to discharge the instantaneous elasticity is also intrinsic to the cross-bridge. Thus, the change in length to discharge force would be independent of the number of cross-bridges and, consequently, independent of force. Alternatively, if the instantaneous elasticity were external to the cross-bridges, it would be governed by its own relationship between force and extension. Reduction of force (and number of cross-bridges) by changing the initial muscle length in this case would reduce the step shortening required. They showed that altering active force by changing the initial muscle length did not alter the size of the step shortening required to discharge the maximum isometric force at any initial length. These results supported the concept that the instantaneous spring-like behavior is an intrinsic cross-bridge property and the cross-bridges act as independent force generators. An important corollary of these studies is that the instantaneous stiffness can be used as an index of the number of attached cross-bridges at any moment. This corollary has been used in numerous studies to assess the effects of various interventions on attached cross-bridge number. There is evidence, however, both mechanical (Higuchi et al., 1995) and x-ray diffraction (Huxley, 1996), which suggests that a significant fraction of the instantaneous stiffness is attributable to the thin filaments. Thus, one should exercise some caution in the interpretation of stiffness measurements in terms of the number of attached cross-bridges.

To summarize a current consensus understanding of muscle contraction, force generation is due to cyclic interaction of myosin heads projecting from the thick filament with actin of the thin filament. These cross-bridges act as independent sites for force generation. Total active force is proportional to the number of activated cross-bridges whose number is geometrically constrained by the extent of filament overlap. The mechanism of cross-bridge force generation is still the subject of considerable investigation. A current model based on biochemical kinetics and cross-bridge mechanics studies is shown in Fig. 46.8. A shift in orientation of the cross-bridge in the strong binding states (steps 3–4) is associated with the force generating step in this model. Of course, any consensus is just an approximation, likely to be refined in the future. Some of the areas of interest to the understanding cross-bridge mechanisms for the next iteration include (Huxley, 2000, Offer and Ranatunga, 2010): significance, location and accurate measurement of cross-bridge compliance; significance of filament compliance, dependence of rate constants on compliance and the independence of cross-bridges.

IV Muscle Energetics

Studies of muscle energetics parallel those of mechanical and biochemical kinetics and have the same ultimate goal understanding the mechanism of mechanochemical transduction at the cross-bridge level (Barclay et al., 2010). Historically, muscle energetics has been associated with the measurement of muscle heat production. A rise in temperature, the first indication of chemical reactions in muscle, can be measured with a temporal resolution which far exceeds that of direct chemical determinations. Moreover, heat measurements were made long before the chemical reactions driving muscle contraction were known (Hill, 1912). In fact, heat measurements and thermodynamic analysis were essential to ultimately identifying the chemical reactions underlying muscle activity. The essential principle comes from application of the first law of thermodynamics which, under constant pressure, states that the change in enthalpy (ΔH) is equal to the sum of heat (Q) production plus work done (W) by the muscle. The change in enthalpy, in turn, can be related to the sum of the changes in number of moles of each species (Δni) multiplied by its specific enthalpy (hi):

(46.3)

(46.3)

Thus, by measuring muscle heat and work restrictions can be placed on potential underlying chemical reactions. For example, one can test whether the enthalpy change in predicted reaction x sufficient to explain the heat plus work produced during contraction.

One of the first application based on of this type of analysis was carried out by Wallace Fenn (1923), who tested a theory known as the viscoelastic model of muscle contraction:

Thus the view came to be accepted that on stimulation a muscle developed a given amount of heat and a given amount of elastic potential energy, both varying with the length of the fibres of the muscle. The amount of elastic potential energy which could be recovered as work depended merely upon the art of the experimenter in arranging his levers and had no relation to the total energy liberated.

In other words, stimulation elicited a fixed or quantal extent of some unknown reaction(s), whose energy was transduced to a fixed amount of heat plus work. A muscle shortening under a load would produce work and, according to this theory, less heat would be produced than a muscle under isometric conditions not producing work. Fenn’s studies showed that the Q + W in a work-producing contraction exceeded the heat produced in an isometric contraction (in which work is minimal). This “Fenn effect” ruled out the viscoelastic model and was important in that theories of muscle energy conversion had to be configured in terms of chemical reactions that were closely coupled to mechanical events. Since that time all models of muscle contraction must pass this stringent energetics test.

The studies of the nature of the chemical reactions coupled to muscle activity, both those immediately coupled mechanical events and those involved in the subsequent recovery by intermediary metabolism, have been closely associated with muscle energetics. The history of the search for the identity of the reactions immediately coupled to muscle mechanical output parallels the history of biochemistry itself. Because of increased understanding of the biochemistry of fermentation and association of lactate with muscle contraction, it was first believed to be a driving reaction, “lactate acid theory”. However, Lundsgaard (1938) showed that muscle treated with iodoacetate (which blocks glycolysis via inhibition of G3P dehydrogenase and thus lactate production) could still contract. Fiske and SubbaRow (1927) showed that inorganic phosphate (Pi) is liberated during contraction, arising not from a glycolytic intermediate, but from a new “phosphagen”, phosphocreatine (PCr). Myosin was known to be an ATPase, but there was little change in ATP concomitant with contractile activity. The connection was made by Lohmann (1934), who discovered an enzyme (creatine kinase) which catalyzes the reversible phosphorylation:

(46.4)

(46.4)

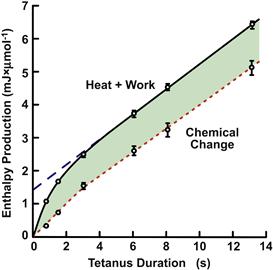

From these observations grew the energetic schema that ATP is the immediate energy source for contraction directly coupled to the myosin ATPase. In intact muscle, PCr rapidly rephosphorylates ADP via the Lohmann reaction (or creatine kinase reaction) and only breakdown of PCr to Cr and Pi can be measured. Tests of whether this was sufficient to account for the change in enthalpy or to account for the free energy change required for the work produced awaited the development of rapid-freezing technology and microchemical analysis of muscle extracts which occurred during the late 1960s. These “energy balance” studies, reviewed in Woledge et al. (1985), tested the validity of Equation 46.3. Under conditions in which metabolic resynthesis was minimized, the measured breakdown of PCr multiplied by its partial molar enthalpy (34 kJ/mol) should be equal to Q + W, if this was the only chemical reaction occurring. As shown in Fig. 46.11, this equality was not valid; Q + W was significantly greater than that accounted for by PCr breakdown (Gilbert et al., 1971). The implication was that there was a “missing” reaction associated with an “unexplained” enthalpy production occurring during contraction and, if valid, would overturn the reigning energetic dogma. Moreover, if heat records could not be interpreted in terms of ATP breakdown (coupled to PCr breakdown), then most kinetic models, starting with the classic Huxley (1957) formulation would need to be revised. Thus, energetics studies were focused on identification of the nature of the unexplained enthalpy and a potential missing reaction associated with contraction.

FIGURE 46.11 Skeletal muscle “energy balance”. Enthalpy (heat+ work) production as a function of tetanus duration is given as the solid line. The expected enthalpy (chemical change times the enthalpy of PCr breakdown, 34 KJ/mol) is plotted as the dotted line. Shaded area represents the unexplained enthalpy. (Adapted from Woledge et al., 1985.)

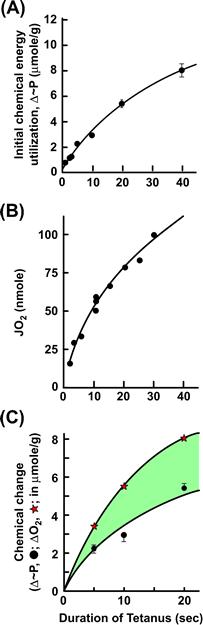

In a parallel fashion, “biochemical” balance studies (Kushmerick, 1983) were also directed at the question of a missing reaction, but with chemical rather than physical techniques. The rationale is that if ATP hydrolysis and its rephosphorylation by PCr are the only reactions occurring during contraction, then the extent of this reaction should be equal to the ATP synthesized during recovery. If resynthesis is governed by theoretical biochemical stoichiometry, then the amount of oxygen consumed during recovery would have been equal to 1/6.5 times the PCr broken down during contraction. The experimental test of this hypothesis is shown in Fig. 46.12. Again an imbalance was observed; the extent of recovery metabolism associated with resynthesis of ATP exceeded that which could be accounted for by PCr breakdown during contraction. Paul (1983), using both physical and biochemical “energy balance” techniques, showed that oxidation of glucose was the only net reaction occurring during a complete contraction/relaxation cycle. Not surprising in today’s worldview, this ruled out a number of theories of the time based on a continuous degradation of muscle for each contraction. The combinations of techniques yield data that indicated that the initial chemical imbalance, i.e. less ATP breakdown than predicted during contraction, is accompanied by additional breakdown of ATP after contraction.

FIGURE 46.12 Skeletal muscle “biochemical energy balance”. (A) The initial high-energy phosphagen (PCr + ATP) breakdown during contraction as a function of tetanus duration. (B) Total recovery oxygen consumption elicited by the contraction durations plotted on the ordinate. (C) The total phosphagen resynthesized based on theoretical stoichiometry and the measured O2 consumption (open stars) and the measured phosphagen breakdown during contraction (filled circles). The shaded area represents the excess of ATP synthesis over the phosphagen breakdown measured during contraction. (Adapted from Kushmerick, 1983.)

A resolution of the “missing” reaction question apparently resided in the discovery of the protein parvalbumin in amphibian muscle and its role as a Ca2+-binding site (Gillis et al., 1982). Parvalbumin binds a significant amount of the Ca2+ released by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) during contraction. This binding is associated with a substantial evolution of heat. There is also evidence that Ca2+ is returned to the SR after the contraction ceases, which would require activity of the Ca2+ pump and concomitant hydrolysis of ATP. This explanation is perhaps the most widely held, but it is not a universal explanation. For example, the biochemical balance studies would suggest that the post-contractile ATP breakdown is proportional to the duration of stimulus, whereas the enthalpy balances apparently indicate that the unexplained enthalpy attains a plateau value. Moreover, some unexplained enthalpy is associated with mammalian striated muscle, which does not contain parvalbumin. Nevertheless, the schema involving ATP as the immediate driving reaction, with PCr as the source of chemical energy for rapid resynthesis in intact muscle appears valid. This is further supported by (1) thermodynamic data indicating that the free energy provided by ATP during contraction is sufficient to account for the work produced (reviewed in Woledge et al., 1985) and (2) many studies using permeabilized muscle indicating that ATP is the only chemical energy source required for contraction.

V Muscle Metabolism

Mechanochemical energy transformation and the breakdown of high-energy phosphagens under various conditions form one branch of study known as muscle energetics. Energy metabolism and intermediary metabolism are two terms often used to describe the other major branch of energetics, that of the study of the metabolic provision of phosphagen in support of muscle activity and the mechanisms of coordination of metabolism with contractility. Muscle mechanical activity is supported by ATP provided by both oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis. Historically, the biochemistry of these pathways often mirrors our understanding of muscle, as this tissue was often the major model for biochemical studies. For the historical aspects with respect to muscle contraction, the treatise of Needham is highly recommended (Needham, 1971).

Perhaps of most recent interest in this field is the re-examination of the theories whereby contractile ATP use is coordinated with metabolic resynthesis of ATP. For skeletal muscle, most prevalent theory is that of acceptor- or ADP-limited respiration. In the case of isolated mitochondria in the presence of substrate, their rate of oxidative phosphorylation, state III is limited by the availability of ADP as the substrate for rephosphorylation. Because the hydrolysis of ATP concomitant with contractile activity is increased, one might anticipate that an increase in ADP could naturally couple the increased usage with synthesis. The creatine kinase reaction, coupled with the amount of PCr in striated muscle, buffers the ATP concentration. Under the assumption that this reaction is in equilibrium, the level of free (i.e. not bound) ADP can be calculated to be in the region of 10 μM. This is also in the range for the Km for ADP for ADP control of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. This mechanism can reasonably well predict PCr breakdown and its resynthesis for a contraction/relaxation cycle in human muscle (Kushmerick, 2005). On the other hand, significant increases in cardiac (Balaban, 2009) and smooth muscle (Hardin et al., 2000) oxidative metabolism occur in the absence of changes in PCr or ATP, indicating that increases in energy metabolism can match the contractile ATP utilization in the absence of changes in ADP. There are a number of hypotheses in this area. The most prominent ones propose regulation of oxidative metabolism by [Ca2+]i (Liu and O’Rourke, 2009) and mechanisms involving a substrate level “push,” e.g. by mobilization of substrate, leading to increased NADH levels.

A second area of growing interest on the metabolism side of muscle energetics is the effect of microcompartmentation of metabolism and its subserved function. Instead of being distributed in a random fashion in solution in the cytosol, many enzymes important in energy metabolism are apparently localized within the cell, often in close apposition to energy-dependent processes. Perhaps the most widely studied system is that of creatine kinase (Ishida et al., 1994) which is localized at the m-line of striated muscle as well as in membrane structures and mitochondria. In permeabilized muscle, endogenous phosphocreatine alone can support contractile activity, suggesting a close relationship between the myosin ATPase and creatine kinase. Similarly, phosphocreatine has been shown to support Ca2+ uptake by sarcoplasmic reticulum isolated from skeletal muscle. The enzymes involved with glycolysis are also localized primarily on the thin filaments and associated with the plasmalemma and sarcoplasmic reticulum. There are increasing numbers of studies for skeletal (James et al., 1996; Levy et al., 2008), cardiac (Weiss and Lamp, 1987) and smooth muscle (Hardin et al., 2000), indicating that ATP provided by glycolysis supports functions different from those dependent on oxidative metabolism. This is particularly striking in smooth muscle, in which the oxidative and glycolytic components of metabolism can be of similar magnitude (Paul et al., 1979). ATP-dependent processes associated with the plasma membrane, such as the Na+-pump and ATP-dependent potassium channels, are apparently particularly dependent on ATP generated by aerobic glycolysis, whereas the ATP requirements for the force generating actin–myosin ATPase interaction are apparently more strongly correlated with oxidative metabolism. The bases and consequences of this cellular organization are not fully understood, but have been suggested to be related to either greater energy transduction efficiency or the need for independent regulation of different cellular functions.

VI Comparative Mechanochemical Function

VIA Striated Muscle

The general features just described are common to all muscle function, however, there is a great variety of muscle types adapted to specialized conditions. Among skeletal muscle, perhaps the most familiar adaptation is the difference between red and white muscle. The nomenclature has a long history and many different schemes exist. Histologically and functionally three major classifications predominate, termed fast glycolytic (FG), slow oxidative (SO) and fast oxidative–glycolytic (FOG), reflecting their gross properties. Most whole muscle contains various mixtures of these three basic muscle fibers and appears pale compared to red muscle, which is composed primarily of SO fibers. The red color is due to the presence of myoglobin, a protein that facilitates the diffusion of oxygen.

These fiber types are adapted for different power requirements. The FG fibers provide large forces that can be rapidly activated and relaxed, but are susceptible to fatigue. Their metabolism depends heavily on glycolytic production of ATP, which can respond rapidly to large changes in energy requirements associated with muscle contraction but has relatively limited capacity. For low level but continuous muscular activity, such as that required by postural muscles, the SO fibers are adapted with a high oxidative metabolic capacity. A lower actin-activated myosin ATPase of the SO fibers relative to FG fibers facilitates a more economical maintenance of force, however, this is accompanied by a slower velocity of shortening.

In primates, FOG fibers are relatively rare and highly specialized muscles (some ocular muscles appear to be composed primarily of this fiber type). Their twitch duration and shortening speed are intermediate between those of SO and FG fibers and are characterized by high levels of both glycolytic and oxidative metabolism. These differences in adaptation also extend to speed of activation, which is approximately three times faster in FG than SO fibers. Cardiac muscle has its own special adaptations and, in many ways, shares similarities with SO skeletal muscle fibers. A third muscle type, smooth muscle, is significantly different from striated muscle and is discussed in detail in the following section.

These gross differences in muscle fiber type have long been studied. Applying advanced molecular biology techniques, we now know that most muscle proteins exist as isoforms. Thus, recent interest has focused on the isoform–function relationships as well as the regulation of the expression of these various isoforms. What is of particular interest is that the number of expressed isoforms – and the theoretical possible variants – far exceed the three gross skeletal fiber types. Detailed information on isoforms is beyond the scope of this text and is available in specialized treatises (Pette and Staron, 2001; Westerblad et al., 2010).

VIB Smooth Muscle

Historically, smooth muscle has been of interest because of its specialized function. It lines the hollow organs, such as blood vessels and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Its structure is less organized than that of striated muscle and thus somewhat less amenable to biophysical experimentation. For many years, its properties have been simply extrapolated from striated muscle. However, it is now clear that while many similarities exist, there are also significant differences. Studies of smooth muscle have significantly increased over the past decade. This can be attributed largely to its clinical relevance in terms of the diseases of industrialized society such as hypertension, asthma and GI motility disorders. However, much of the current interest has arisen from the discovery that the regulatory mechanisms at the contractile filament level are radically different from those of striated muscle.

Smooth muscle can develop isometric forces per cross-sectional area that are equal to or greater than those generated by striated muscle. This is all the more surprising in that the myosin content of smooth muscle is considerably less (about one-fifth) than that of striated muscle. These large forces can be maintained with a rate of ATP utilization that is 100-to 500-fold lower than the corresponding rate in skeletal muscle. The trade-off for high forces and economy of force maintenance is apparently shortening velocity, which is much slower (up to 1000-fold) than that in striated muscle. The efficiency, in terms of work per ATP, is also somewhat lower (approximately one-fifth that of skeletal muscle), however, the data here are less extensive. The key question then is how does smooth muscle accomplish these specialized functions given that its contractile apparatus uses basically similar actin and myosin components?

VIB1 Smooth Muscle Structure and Its Relationship to Function

The structure of smooth muscle is shown in Fig. 46.13. Smooth muscle cells are smaller than skeletal muscle, with maximum diameters of the spindle-shaped cells in the range 10–20 μm. Filament structure is less organized, with no distinct sarcomeric or banding structure, hence the name “smooth”. There are no Z-bands, but actin filaments are organized through attachment to specialized cytoskeletal regions called dense bodies or patches. These areas contain α-actinin, a Z-band protein, which further strengthens this analogy. It is also likely that these structures mediate transmission of force between cells. The ratio of thin to thick filaments is much higher in smooth muscle (≈15:1) than in striated muscle (2:1).

FIGURE 46.13 Morphology of relaxed and contracted smooth muscle. (A) This diagram represents a portion of a relaxed smooth muscle cell, highlighting the arrangement of the actin-containing thin filaments and the myosin-containing thick filaments. This rendering is greatly simplified from the actual arrangement. From the longitudinal orientation, thin filaments arise at dense bodies and project to interact with thick filaments, forming the contractile apparatus. In the cross-section, the filaments are distributed in a non-uniform manner, with thick filaments forming clusters surrounded by groups of thin filaments. This arrangement is shown in the electron micrograph (circled), which is a cross-section of a relaxed visceral smooth muscle cell. (B) A contracted smooth muscle cell. The notable differences from the relaxed cell shown in part (A) are that, in the longitudinal views, the thin filaments overlap considerably more of the thick filaments, drawing the dense bodies closer together and shortening the cell. In cross-section, the thin and thick filaments are randomly distributed to form a uniform pattern. The electron micrograph is a cross-section of a contracted visceral smooth muscle cell which shows more uniform distribution of the thin and thick filaments. (Diagrams are modified from Heumann, 1973.)

This latter observation raises the question of whether structural factors could account for these functional differences. The answer clearly depends on the mechanism of contraction in smooth muscle. It is assumed, by analogy to striated muscle, that a sliding-filament mechanism is involved in smooth muscle contraction. There is much less direct evidence than skeletal muscle, but the available data are consistent with this theory. Primarily, the evidence in intact tissue is largely limited to the dependence of active force on length, which is qualitatively similar to that of striated muscle. Smooth muscle appears to shorten to a greater extent, 0.2–0.4 of the optimal length for force generation (Herlihy and Murphy, 1973; Paul and Peterson, 1975), compared to 0.6 for skeletal muscle. On the descending limb of the active force–length curve, the decline may be more rapid, but the large passive forces in this region preclude precise measurements. There is also an element of plasticity in these force–length relations which show a hysteresis, dependent on how the measurements are made (Peterson and Paul, 1974; Seow and Pare, 2007). The loose organization of myofilaments is not readily amenable to direct structural measurements which precludes conclusive evidence based on comparison of the extent of thin–thick filament overlap to force–length behavior. From “motility assays,” in which actin filaments are observed to move on a myosin-coated surface, or myosin-coated beads move on actin filament networks (Harris and Warshaw, 1993), one can infer that folding of filaments is not essential to motion, consistent with a sliding-filament model. The only difference between striated and smooth muscle myosin in these experiments is a slower velocity observed with smooth muscle myosin.

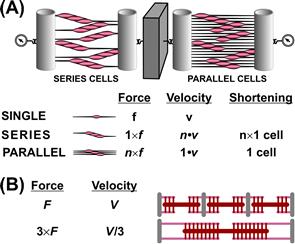

Assuming that an analogous sliding-filament mechanism operates in smooth muscle, what types of structure could account for the differences in function? Force is proportional to the number of cross-bridges in parallel, whereas shortening velocity and the maximal shortened length are related to the number of fundamental units in series. Models of arrangement of cells or sarcomeres yielding an increase in force and holding economy while reducing velocity are shown in Fig. 46.14. While increasing the number of cells in parallel (Fig. 46.14A) works in the appropriate direction (large force, low tension cost), it falls short of true smooth muscle behavior in that the amount of total tissue shortening in this model is very limited. Smooth muscle can shorten to relatively short lengths; some 20–30% of initial tissue length is not uncommon. In the model of Fig. 46.14A, the absolute length change would be that attributable to shortening of only one cell and would not account for the shortening of any macrosize tissue.

FIGURE 46.14 (A) Parallel and series models of force transmission in a smooth muscle-containing tissue. Parallel arrangement increases total force, but with a decrease in velocity and total shortening compared with cells coupled in series. (B) Parallel and series model at the level of the sarcomere. Both sliding filament models have the same myosin content, but it is arranged in short (top) and long sarcomeres (bottom).

In Fig. 46.14B, different mechanical properties are associated with the assembly of the sarcomere. Longer myosin filaments and, consequently, longer sarcomeres are associated with more parallel cross-bridges and higher forces. However, for a given myosin content, this arrangement has fewer sarcomeres in series and hence a slower overall velocity. Moreover, if the individual myosin cross-bridge ATPase is not altered, one would have a similar ATP use for both models and thus the longer sarcomere version would have a greater economy (force maintained per rate of ATP hydrolysis) or a lower tension cost (reciprocal of economy). These changes are in the direction that distinguishes smooth muscle from skeletal muscle. The question then is how much of the difference between skeletal and smooth muscle can be related to simply the “mechanical advantage” of longer sarcomeres? Although no obvious sarcomeric structure exists for smooth muscle, the length of the myosin filament of smooth muscle relative to striated answers this question. There is evidence that some smooth muscles, particularly in invertebrates, such as the scallop or mussel, whose sarcomere lengths may be up to 10-fold greater than mammalian skeletal muscle, make use of this mechanical advantage. However, for mammalian tissues, myosin filament length has been estimated at approximately 2.2 μm (Somlyo, 1980), a figure not significantly different from that of striated muscle (1.6 μm). The differences in contractile properties between smooth and. skeletal muscles would thus appear to reside largely in the nature of the smooth muscle myosin molecule and its intrinsically lower ATPase.

VIB2 Regulation of Smooth Muscle Contractility

Regulation of contractility can be divided into (1) mechanisms for control of [Ca2+]i and (2) mechanisms for transduction of the Ca2+ signal to activation of the contractile apparatus. Regulation of [Ca2+]i is considered elsewhere and the focus here is on transduction mechanisms.

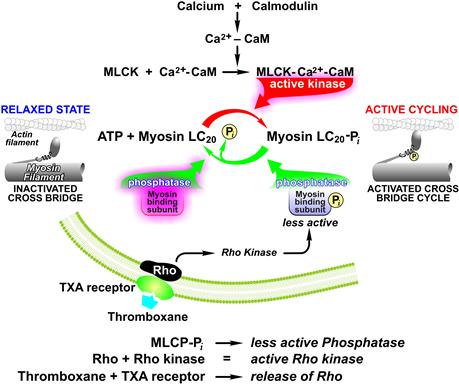

Up to the mid-1970s, regulation of mammalian smooth muscle contractility was based largely by analogy to striated muscle and considered to be a “thin-filament” regulated system; i.e. one in which troponin is the Ca2+ receptor and tropomyosin is the transducing element. It was quite a surprise when this canonical theory was shown not to be valid for mammalian smooth muscle. Several lines of evidence led to the current, widely accepted view that phosphorylation of the 20 kDa regulatory light chain of myosin (MRLC-Pi) is the primary transduction site for the Ca2+ signal (Hartshorne and Siemenkowski, 1981; Kamm and Stull, 1985; Hartshorne, 1987; de Lanerolle and Paul, 1991). Although tropomyosin is known to be a major smooth muscle protein, the Ca2+ transducer, troponin, is not present in smooth muscle. Proving that a protein is absent is difficult and that proof came slowly. Smooth muscle actomyosin also proved considerably different from that of striated muscle. One aspect was that as its purity increased, its ATPase activity decreased, the opposite of striated actomyosin. This suggested that purified smooth muscle actomyosin requires activation; in contrast to striated muscle actomyosin which is constitutively active, and requires de-inhibition of the associated troponin–tropomyosin inhibitory proteins. This was rigorously tested by “competition” experiments. In these experiments, the Ca2+ sensitivity of the actin-activated, Mg2+-ATPase of myosin was measured using “unregulated” thin filaments (i.e., purified actin without troponin and tropomyosin). Striated muscle myosin showed little Ca2+ sensitivity, whereas mammalian smooth muscle myosin retained Ca2+ sensitivity, indicating that the site of its regulation was on the myosin itself. The regulatory site was identified when it was discovered that the ATPase activity of smooth muscle myosin was dependent on phosphorylation of the 20-kDa regulatory light chain (MRLC) of the myosin hexamer. This phosphorylation involves Ca2+ binding to calmodulin, the ubiquitous Ca2+ binding protein, which in turn binds and thereby activates myosin light chain kinase (MLCK). This kinase is rather remarkable in that MRLC is its only substrate, rare among most kinases which often have multiple targets.

Several lines of evidence supported this thick filament regulatory mechanism. One strategy was to alter MRLC-Pi independent of [Ca2+]i through manipulation of the kinase or phosphatase. Inhibition of MLCK led to relaxation and dephosphorylation in the presence of Ca2+. Another path involved the proteolysis of MLCK to obtain a constitutively active fragment which, added to permeabilized smooth muscle, generated a contraction in the absence of Ca2+ which was indistinguishable from that induced by Ca2+. Another line involved targeting the phosphatase; addition of myosin phosphatase enriched fractions relaxed contracted smooth muscle (Rüegg et al., 1982). Inhibition of myosin phosphatase also leads to smooth muscle contraction. Taken in total, these results suggest that myosin light chain phosphorylation is the major regulatory site and is necessary for activation.

In the past 10 years, the biggest surprise in the regulation of smooth muscle is the importance played by modulation of phosphatase activity (Somlyo and Somlyo, 2000). Myosin phosphatase activity is regulated by it targeting subunit (MYPT1) or myosin binding subunit. MYPT1 binds to the catalytic subunit of type 1 phosphatase and also acts as an interactive platform for many other proteins, in particular, myosin filaments. Phosphorylation of MYPT1 weakens the binding to myosin and, consequently, decreases its apparent phosphatase activity. There are several phosphorylation sites: S696 and S854 are PKA/PKG sites; T697 and T855 are the inhibitory/regulatory sites phosphorylated by several kinases most notably Rho-kinase (ROK) (Matsumura and Hartshorne, 2008).

Activation of smooth muscle contraction by MRLC phosphorylation/dephosphorylation provides multiple points for modulation. Phosphorylation of MLCK by cAMP dependent kinase weakens its binding to calmodulin and leads to Ca2+ desensitization of contraction; i.e. less force generated for a given [Ca2+]i than control. On the other hand, there are two major paths currently known to decrease phosphatase activity, thus leading to an increase in Ca2+ sensitivity. In addition to Rho-Kinase, C-kinase phosphorylation of a small inhibitory protein, CPI-17, forms a complex that retards dephosphorylation of MYPT1 decreasing myosin phosphatase activity (Eto et al., 2004). In some smooth muscles, myosin phosphatase can clearly dominate MLCK phosphorylation, such as inhibition of the phosphatase by Rho kinase, a major player in activation. For example, inhibition of Rho kinase can lead to the complete relaxation of receptor-mediated stimulation (Nobe and Paul, 2001). A schematic for the regulation of MRLC phosphorylation/dephosphorylation is shown in Fig. 46.15.

FIGURE 46.15 Schematic showing the mechanisms for phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of myosin regulation light chains and contractile state of smooth muscle.

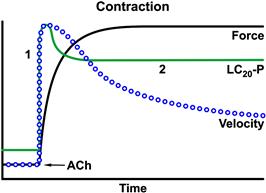

Whether myosin light chain phosphorylation is sufficient as a regulatory mechanism or indeed has roles in addition to actomyosin activation is open to question. A number of experimental observations suggest that smooth muscle regulation may be more complex than initially envisioned. Figure 46.16 summarizes the time courses of several parameters after stimulation. Isometric force increases monotonically and then maintains a plateau value, whereas MRLC-Pi rapidly increases to a maximum achieved early in the contraction and then decreases. The extent of the decline in the MRLC-Pi is controversial and this is likely attributable to different smooth muscle types, dependence on the nature of the stimulus and measurement technique. Since force is usually assumed to reflect the number of activated cross-bridges, the decline in MRLC-Pi with maintained or increasing force suggests that this is not a simple on-off switch and/or other regulatory factors may play a role. Moreover, near maximal forces are attained with MRLC-Pi levels considerably lower than 100%, often reported to be in the 15–40% range, which further questions its role as a simple switch. The decline in MRLC-Pi also parallels that of [Ca2+]i and, interestingly, to the decline in shortening velocity and ATPase activity. In view of these observations, Murphy and colleagues (Hai and Murphy, 1988, 1989a) suggested that MRLC-Pi might be a regulator of contractile velocity. They coined the expression “latch” for the state of maintained force with reduced MRLC-Pi and slower contraction speeds. Latch bridges, or cross-bridges, in this state were initially postulated to be non- or slowly cycling and thus they reduced the overall tissue velocity by acting as a type of internal load on the more rapidly cycling bridges. As force retained its dependence on Ca2+ in the latch state, it was postulated that latch bridges may be regulated by a system different from MRLC-Pi.

FIGURE 46.16 Relations between isometric force, maximum shortening velocity and myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation (LC20-P) and the duration of stimulation. Data are for tracheal smooth muscle (adapted fromde Lanerolle and Paul, 1991). The decrease in velocity at times when force is maintained is the basis for the latch bridge theories.

Currently, there are two major classes of theories for latch behavior, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Thin-filament regulatory mechanisms based on several actin-binding proteins, namely, leiotonin, caldesmon and calponin, have been suggested. A common feature is that they are all proposed to be inhibitory and, for the latter two, the interaction with actin is sensitive to Ca2+calmodulin. Although all are promising in terms of the ability to inhibit myosin ATPase activity in the test tube, the relevance to intact smooth muscle has yet to be unequivocally demonstrated. As smooth muscle myosin requires activation, these systems could only be ancillary. Based on the ability of MRLC-Pi to activate smooth muscle in the absence of Ca2+, it is difficult to postulate that these systems can be inhibitory in the sense that they regulate activation on an “on-off” basis. However, these systems could regulate cross-bridge cycling and thus velocity (Kim et al., 2008), but more evidence of this is needed.

An alternative hypothesis suggested by Murphy and Rembold (2005) does not require regulatory components beyond myosin light chain phosphorylation–dephosphorylation. A version of their model is shown in Fig. 46.17. They postulate that if a phosphorylated cross-bridge were dephosphorylated while attached, its detachment rate would be significantly slower than if it were to remain phosphorylated. The kinetic scheme of Fig. 46.17 is sufficient to fit the available data on the time courses of force and MRLC-Pi. It can also predict the time course of ATP utilization, which also decreases similarly to velocity, with stimulation duration. This scheme also predicts that the “futile” cycle of myosin light chain phosphorylation–dephosphorylation is the dominant (≈85%) source of ATP utilization, which was challenged based on the available smooth muscle energetics data (Paul, 1990). This discrepancy was resolved when it was shown (Wingard et al., 1997) that myosin phosphorylation–dephosphorylation can be an appreciable source of ATP utilization during the initial force development when levels of MRLC-Pi are high, but rapidly drops paralleling Ca2+, MRLC-Pi and velocity. Thus, the high economy of tension maintenance in smooth muscle or lower tension cost in smooth than striated muscle includes a low intrinsic actomyosin ATPase (≈100-fold), longer sarcomeres (≈1.5-fold) and decreasing the cross-bridge cycle rate at constant force (≈3-fold). The role of latch bridges or thin filament proteins in the latter is yet to be fully resolved and universally accepted.

FIGURE 46.17 A schematic model of the interaction of smooth muscle myosin cross-bridges with actin filaments. The transition from state 1 to state 2 represents the Ca2+-calmodulin dependent phosphorylation/dephosphorylation activation mechanism proposed for smooth muscle regulation. The cycle of interaction (states 2–5) hydrolyzes 1 ATP molecule and generates 1 quantum of tension with each pass. Only the angulated attached myosin cross-bridge (state 4) generates isometric force. The inherent speed of the cycle is much slower in smooth muscle than in striated, with the ATP-dependent dissociation step (state 4–5) apparently being slower. The dashed arrows indicate formation of a proposed dephosphorylated actomyosin cross-bridge (Hai and Murphy, 1989b), which dissociates only very slowly and may be responsible for the latch state of vascular smooth muscle.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Balaban RS. Domestication of the cardiac mitochondrion for energy conversion. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:832–841.

2. Barclay CJ, Woledge RC, Curtin NA. Inferring crossbridge properties from skeletal muscle energetics. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2010;102:53–71.

3. de Lanerolle P, Paul RJ. Myosin phosphorylation/dephosphorylation and regulation of airway smooth muscle contractility. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:L1–14.

4. Eto M, Kitazawa T, Brautigan DL. Phosphoprotein inhibitor CPI-17 specificity depends on allosteric regulation of protein phosphatase-1 by regulatory subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8888–8893.

5. Fenn WO. A quantitative comparison between the energy liberated and the work performed by the isolated sartorius muscle of the frog. J Physiol. 1923;58:175–203.

6. Fiske CH, SubbaRow Y. The nature of the “inorganic phosphate” in voluntary muscle. Science. 1927;65:401–403.

7. Gilbert C, Kretzschmar KM, Wilkie DR, Woledge RC. Chemical change and energy output during muscular contraction. J Physiol. 1971;218:163–193.

8. Gillis JM, Thomason D, Lefevre J, Kretsinger RH. Parvalbumins and muscle relaxation: a computer simulation study. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1982;3:377–398.

9. Gordon AM, Huxley AF, Julian FJ. The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres. J Physiol (Lond). 1966;184:170–192.

10. Hai C, Murphy R. Crossbridge phosphorylation and the energetics of contraction in swine carotid media. In: Paul R, Elzinga G, Yamade K, eds. Muscle Energetics. New York: A.R. Liss Publisher; 1989a;:253–264.

11. Hai CM, Murphy RA. Regulation of shortening velocity by cross-bridge phosphorylation in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:C86–C94.

12. Hai CM, Murphy RA. Ca2+, crossbridge phosphorylation, and contraction. Annu Rev Physiol. 1989b;51:285–298.

13. Hardin CD, Allen TJ, Paul RJ, eds. Metabolism and energetics of vascular smooth muscle. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000.

14. Harris DE, Warshaw DM. Smooth and skeletal muscle actin are mechanically indistinguishable in the in vitro motility assay. Circ Res. 1993;72:219–224.

15. Hartshorne D. Biochemistry of the contractile process in smooth muscle. In: Johnson L, ed. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. New York: Raven Press; 1987;:423–482.

16. Hartshorne DJ, Siemankowski RF. Regulation of smooth muscle actomyosin. Annu Rev Physiol. 1981;43:519–530.

17. Herlihy JT, Murphy RA. Length-tension relationship of smooth muscle of the hog carotid artery. Circ Res. 1973;33:275–283.

18. Heumann HG. Smooth muscle: contraction hypothesis based on the arrangement of actin and myosin filaments in different states of contraction. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1973;265:213–217.

19. Higuchi H, Yanagida T, Goldman YE. Compliance of thin filaments in skinned fibers of rabbit skeletal muscle. Biophys J. 1995;69:1000–1010.

20. Hill AV. The heat-producton of surviving amphibian muscles, during rest, activity, and rigor. J Physiol. 1912;44:466–513.

21. Hill AV. The heat of shortening and the dynamic constants of muscle. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1938;126:136–195.