Chapter 52

Bioluminescence

Chapter Outline

III. What is Bioluminescence? Physical and Chemical Mechanisms

IV. Luminous Organisms: Abundance, Diversity and Distribution

V. Functions of Bioluminescence

VII. Dinoflagellate Luminescence

VIII. Coelenterates and Ctenophores

X. Other Organisms: Other Chemistries

I Summary

Bioluminescence is an enzymatically-catalyzed chemiluminescence, a chemical reaction that emits light. Though relatively rare, it occurs in a phylogenetically-wide range of species, primarily marine, ranging from bacteria to vertebrates, and has many independent evolutionary origins. Thus, structures of the genes and proteins, as well as the physiological, biochemical and regulatory mechanisms involved, are very different. The principal biochemical components are referred to as luciferin and luciferase, terms that cannot stand alone, being different structurally in different groups. Luminescence provides a selective advantage mediated through its detection and responses by other organisms; its functions may be classed as defensive, offensive or for communication. Physiological control, biochemical mechanisms and functions in four of the major groups, and several less well-known ones, are described. Regulatory mechanisms include autoinduction (quorum sensing; bacteria), action potentials and voltage-gated membrane channels (dinoflagellates, protons; coelenterates, calcium), circadian control (dinoflagellates) and oxygen mobilization (beetles).

II Introduction

Unlike most physiological processes, the mechanisms and biochemical components involved in bioluminescence are not the same in different phylogenetic groups, thus indicating that light emission originated many times independently in evolution. For example, fireflies and all beetles use ATP and their flash is triggered by a pulse of oxygen, while flashes of coelenterates are triggered by calcium and ATP is not involved, while bacteria utilize a flavin and dinoflagellates a tetrapyrrole as luciferins. But this is but the tip of the iceberg and, while knowledge of the chemistries and physiological mechanisms of a large fraction of such systems is still below the surface, those that have been elucidated provide important knowledge of physiological mechanisms.

In addition to contributing to fundamental knowledge, some systems have provided unique tools for investigating and understanding other basic physiological processes. Notable, to be sure, was the confirmation in 1976 of the theory that calcium triggers muscle contraction, demonstrated with single barnacle cells injected with the purified intermediate of the coelenterate bioluminescence system (aequorin); upon stimulation, the earliest event recorded was the onset of light emission. Even more familiar and now routinely used at the laboratory bench are genes of luciferases and green fluorescent protein (GFP; the light emitting protein in coelenterates) as reporters. Thereby, a wide variety of molecules and the time course of diverse processes can be visually localized at the cellular level.

Although bioluminescence is rather rare in nature, and in that sense a curiosity, it has several different and fascinating functions. Flashes may be used in several different ways, in fireflies to communicate in courtship or in fish to startle, either to escape predators or capture prey. Its use by many fish and other marine organisms to camouflage the silhouette by emitting a constant ventral glow (intensity adjustable) cries for a study of the physiological mechanism whereby the down-welling light intensity is detected and used to control the intensity of the bioluminescence.

The physiological mechanisms, biochemical systems and genes responsible are similarly very different, not evolutionarily conserved, and evidently originated and evolved independently. How many times this may have occurred is difficult to say, but it has been estimated that present day luminous organisms come from as many as thirty or forty different evolutionarily distinct origins (Hastings, 1983; Hastings and Morin, 1991; Haddock et al., 2010).

The four major systems to be described, as well as the lesser well-researched ones, exemplify differences in all aspects, highlighting their independent origins. The luciferases of each of the four have been cloned and sequenced and crystal structures determined. The luciferins and other biochemical components, as well as the identities of the emitting species, are different and known for all. The physiological mechanisms whereby light emission is controlled range from regulation of gene expression and membrane action potentials and channels to osmotically controlled triggering and shutter mechanisms.

III What is Bioluminescence? Physical and Chemical Mechanisms

Bioluminescence displays, though sometimes obscured by the now-ubiquitous artificial illumination, are bright enough to be seen by other animals and do not include the very dim light emitted by some cells, which is detectable by sensitive instruments now available. This is a chemiluminescence, sometimes attributable to reactions of active oxygen species. And yes, bioluminescence is itself a chemiluminescence (McCapra in Herring, 1978; Wilson, 1985; Campbell, 1988), but distinct in that the reaction is catalyzed by enzymes (generically referred to as luciferases), as well as by the fact it can be seen by eye.

Bioluminescence does not come from or depend on light absorbed by the organism. It derives from a highly exergonic (energy yielding) chemical reaction in which excess energy is transformed into light energy instead of being all lost as heat (Wilson and Hastings, 1998). Thus, in the reaction of substance A with molecular oxygen, one of the reaction products is formed in an electronically excited state (B∗), which then emits a photon (hν). In all known cases, the reactants remain bound to the luciferase throughout, so that the emission comes from a protein-bound fluorophore (B∗, in this example).

More generally, the term luminescence refers to any light emission in which energy is specifically channeled to a molecule so that an excited state is produced, not related or due to the temperature. Thus, in addition to chemiluminescence and bioluminescence, these include fluorescence and phosphorescence, in which the excited state is created by the prior absorption of light, as well as triboluminescence and piezoluminescence, involving crystal fracture and electric discharge, respectively. The color is a characteristic of the excited molecule, irrespective of how it was excited. But, as elaborated below, the color may be greatly affected by protein binding, as shown for some bioluminescent systems.

Luminescence is contrasted with incandescence, in which excited states are produced by virtue of the temperature, and the energy is thermal. An example is the light bulb, soon to be phased out for household use, in which a filament is heated, and the color of the light depends on the temperature (“red hot” reflecting a lower temperature than “white hot”). The phasing out is because of its relative inefficiency, due in part to the fact that, unlike luminescence, photons are emitted over a wide range of frequencies, most not in the visible range.

The energy (E) of the photon is related to the color or frequency of the light and is given by the equation E = hν, where h is Planck’s constant and ν the frequency. In the visible-light range, E is quite large in relation to most biochemical reactions. Thus, in visible wavelengths the energy released by a mole of photons (6.02 × 1023) is about 50 kcal, much more than the energy from the hydrolysis of a mole of ATP, about 7 kcal. In cells, chemical energy from the absorption of a visible photon can power photosynthesis, or it can do damage (mutation; photodynamic action, which can kill). Conversely, it takes a reaction yielding considerable energy to result in an excited state and visible photon.

A question of fundamental importance, then, is what kind of chemical process possesses enough energy, and evidently in a single step (an important point), to populate (create) an excited state? A clue is the fact that both chemi- and bioluminescence in solution require oxygen, which in its reaction with a substrate forms an organic peroxide. The energy from the reaction of such peroxides to form more stable products – which should generate up to 100 kcal per mole – is ample to account for a product in an electronically excited state. Thus, while all known bioluminescent reactions involve peroxide intermediates, their identities differ, because their luciferins (substrates) and also luciferases differ.

The terms luciferin and luciferase are not sufficient for their identification in a given organism. Dubois first showed in 1885 that bioluminescence in beetles could occur in cell-free extracts, with the emission continuing for minutes, or hours in some cases. He demonstrated that the reaction could be characterized as having two components, one heat stable (luciferin) and the other more labile to heat (luciferase). Luciferin was named from the Latin as the component responsible for the light emission (light bearing) and the luciferase as the enzyme. For half a century thereafter, in spite of clear evidence to the contrary, the fact that the luciferins and luciferases from different groups of organisms are different was ignored and the terms were used with abandonment for all species. Today, the persistence of the use of the terms in research publications without naming the organism can be confusing. Luciferin and luciferase are generic terms and, to be correct and specific, each must be identified with the organism, thus firefly luciferin or bacterial luciferase, for example.

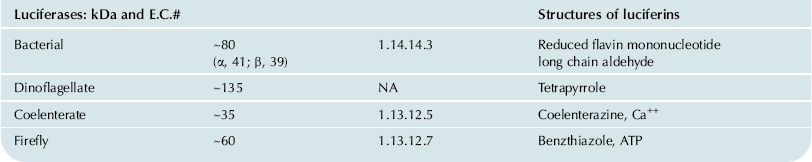

While luciferases are single proteins, the luciferin fraction may contain more than one substrate, as well as co-factors (Table 52.1). For example, the firefly system involves both ATP and a unique luciferin (a benzothiazole), while the bacterial reaction involves the mixed function oxidation of two substances, reduced flavin mononucleotide and a long chain aliphatic aldehyde. In such cases, there has been some confusion as to which should be called the luciferin, since both contribute to the energy released in the reaction. Sticking to the etymology of the original definition, the benzothiazole and flavin, respectively, are the luciferins in those systems (Hastings, 2011).

TABLE 52.1. The Different Luciferases and Luciferins

IV Luminous Organisms: Abundance, Diversity and Distribution

While indeed rare in terms of the total number of luminous species, bioluminescence is phylogenetically diverse, being found in more than 13 phyla (Herring in Herring, 1978). These include bacteria, unicellular algae and fungi, as well as animals ranging from jellyfish, annelids and molluscs to shrimp, fireflies, echinoderms and fishes. Luminescence does not occur in higher plants or in vertebrates above the fishes (Cormier in Herring, 1978). It is also absent in several invertebrate phyla. In some phyla or taxa, a substantial proportion of the genera are luminous (e.g. ctenophores, ≈50%; cephalopods, >50%; echinoderms and annelids, ≈4%). In some cases, all members of a luminous genus emit light, but in others there are both luminous and non-luminous species.

Of the 30 or 40 groups that are believed to be evolutionarily independent, some are found even in different taxa within a phylum or class. Fewer than half of these have been studied in detail and some knowledge of their luciferins and luciferases is available for only about a dozen. Although luminescence is prevalent in the deep sea (Herring, 1985a, b), where there is no sunlight, it is not associated especially with organisms that live in total darkness. There are no known luminous species either in deep fresh water bodies, such as Lake Baikal, Russia, or in the total darkness of terrestrial caves. There are luminous dipteran larvae (Arachnocampa) that live near the mouths of caves in New Zealand and Australia, but they also occur in culverts and the undercut banks of streams, where there is considerable daytime illumination. Although insect displays are among the most spectacular, bioluminescence is relatively rare in the terrestrial environment (<0.2% of all genera). Some other terrestrial luminous forms are millipedes, centipedes, earthworms and snails, but in none of these is the display especially bright.

For reasons that are still not known, bioluminescence is most prevalent in the marine environment (Haddock et al., 2010), especially at mid-ocean depths (200–1200 m), where daytime illumination fluxes range between ≈10−1 and 10−12 μW/cm2. In some such locations it may occur in over 95% of the individuals and 75% of the species in fish, and in shrimp and squid about 85% of the individuals and 80% of the species. The mid-water luminous fish Cyclothone is considered to be the most abundant vertebrate on the planet. Where high densities of luminous organisms occur, their emissions can exert a significant influence on the communities and may represent an important component in the ecology, behavior and physiology of these organisms. Above and below mid-ocean depths, luminescence decreases to <10% of all individuals and species. At abyssal depths it may be somewhat higher (≈20%), while among coastal species, less than 2% are bioluminescent.

V Functions of Bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is unusual biologically because it is a clear and well-documented example of a function that is not metabolically essential but one that may confer an advantage on the individual. While bioluminescence has evidently arisen independently many times, it may also have been lost many times in different evolutionary lines, not being truly essential. No one can tell.

Bioluminescence may be thought of as a bag of tricks: the light can be used in different ways and for different functions. Most of the perceived functions of bioluminescence may be classed under three main rubrics: defense, offense and communication; a fourth less common one is to enhance propagation (Table 52.2).

TABLE 52.2. Functions of Bioluminescence

| Category | Function | How achieved |

| Deter, escape predators (defense) | Camouflage | Ventral emission, symbiosis |

| Startle, frighten | Brief bright flashes | |

| Decoy, diversion | Luminous cloud, sacrificial lure | |

| Predators learn to avoid | Aposematism; danger signal | |

| Aid in predation (offense) | Startle | Brief bright flashes |

| Attract prey | Lure | |

| Aid in vision | See and capture prey | |

| Communication | Courtship, mating | Flash signals |

| Species recognition | Photophore patterns | |

| Propagation | Bacterial light emission | Attract feeders, enhance growth |

Important defensive strategies are to frighten, to serve as a decoy, to provide camouflage, or aposematic, serving as a warning to would-be predators (e.g. the animal is distasteful) (Grober, 1988). Organisms may be frightened or diverted by flashes, which are typically bright and brief (0.1 s), too fast to allow a predator to locate motile prey; light is emitted in this way by many organisms, and experimental studies confirm that flashes can indeed frighten (Morin, 1983).

An organism can use a glow defensively by creating a luminous decoy to attract and divert a predator, while it slips off itself under the cover of darkness. This is done by several organisms, such as squid, which squirt luminescence instead of ink; ink would be useless in total darkness. Some organisms sacrifice more than light; in scaleworms and brittle stars, a part of the body may be automized (broken off) and left behind as a luminescent decoy to attract the predator. In these cases, the animal flashes while intact but the detached part glows.

A clever method for evading predation from below is to camouflage the silhouette by emitting light continuously matching the color and intensity of the downwelling background light. By analogy with countershading in reflected light, this is called counterillumination. Consider a plane in the sky during the day. If it could emit light from its belly matching the sky behind, it would be invisible from below. Actually, it is not necessary for the entire surface to emit light; emission by only a part would mean that the object would no longer look like a plane. This can be called disruptive illumination and many luminous marine organisms, including fish and the bobtail squid, use this to help escape detection. Many culture symbiotic luminous bacteria for use as the light source (McFall-Ngai and Morin, 1991). Another novel defensive strategy has been dubbed the burglar alarm: dinoflagellates flash when grazed upon, which may reveal the grazers and enhance predation on them, thereby reducing grazing on the dinoflagellates (Abrahams and Townsend, 1993).

There are also several ways in which luminescence can aid in predation. Several of these, such as illuminating for vision, may be of value for both offense and defense; offensively, prey may be thereby seen and captured, as flashlight fish do (Fig. 52.1). And flashes, which are more typically used defensively, can be used offensively in order temporarily to startle or blind prey. A glow can also be used offensively: it can serve as a lure. The prey is attracted to the light but is then captured by the organism that produced the light. This is practiced by the deep-sea angler fishes; they also culture symbiotic luminous bacteria for the light source.

FIGURE 52.1 The flashlight fish (Photoblepharon) showing the light organ harboring luminous bacteria just below the eye. (By permission J.G. Morin.)

Communication involves information exchange between individual members of a species and luminescence is used for this in several groups, including annelids, crustaceans, insects, squid and fishes (Herring, 1990). The most common use of the light is for courtship and mating, as in fireflies (Lloyd, 1977, 1980; Buck, 1988). There are also numerous examples in the ocean (Herring, 1990). In the annelid (syllid) fireworm Odontosyllis, a truly extraordinary display occurs as the animals engage in mating, which occurs daily for only a few days after the full moon, timed to start a few minutes after sunset. Readily observed in many parts of the world (e.g. Bermuda), the females come to the surface and swim in a tight luminous circle. A luminous male streaks from below and joins the female; eggs and sperm are shed in the ocean. Another kind of behavior occurs over shallow reefs in the Caribbean: male ostracod crustaceans produce complex species-specific trains of secreted luminous material, ladders of light, which attract females (Fig. 52.2) (Morin and Cohen, 1991, 2010).

FIGURE 52.2 Video recording of pulses of light secreted sequentially by males of the ostracod crustacean Vargula about 1 cm apart in shallow water in the Caribbean as a display in courtship. The several different beads come from different animals active at the same time in the same area. (By permission J.G. Morin and Martin Dohrn.)

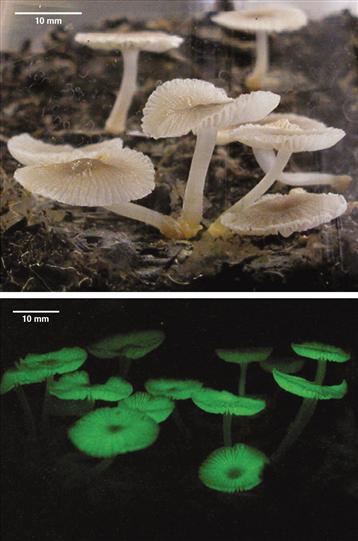

There remain some cases for which it is difficult to know what the function of the light emission may be. In some cases, it may be an aposematic signal, as coloration is in some animals, but not so recognized. But where the light is not seen, this would not explain it. For example, in the luminous fungi (Fig. 52.3) (Desjardin et al., 2008, 2010), which emit light continuously, the luminous cap is believed to attract insects, which would serve to disperse spores. But, in some, only the mycelium is luminous, and it is essentially never seen, living underground or inside a decaying tree. And no good explanation for luminescence in earthworms, where emission is also underground, has been advanced. The function of luminescence in these and some other cases remains to be understood.

FIGURE 52.3 Photos taken in room light (above) and by their own light of the bioluminescent mushroom Mycena chlorophos. Caps but not stipes are luminous; in other species only stipes are luminous, in yet others both emit light, and in one only the underground mycelium emits. (The specimens were grown and the photo was taken by Dr. Eiji Nagasawa, reproduced by permission).

VI Bacterial Luminescence

VIA Regulation by “Quorum Sensing” (Autoinduction) and by Shutters or Filters

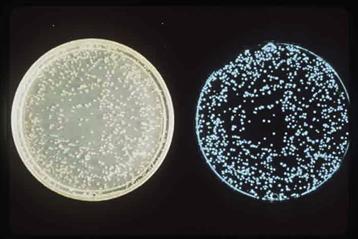

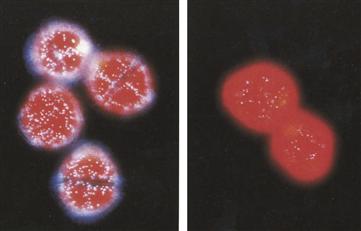

Bacteria in general had long been regarded as cells that do their own thing, simply dividing and multiplying with no regard for other bacterial cells around them – no “communication”. And light emission from luminous bacteria (Fig. 52.4) was well characterized as being continuous and its luminescence not typically subject to a rapid change. The discovery in luminous bacteria of “autoinduction” (Nealson et al., 1970), now referred to as “quorum sensing”, revealed massive and environmentally significant regulation at the transcriptional level (Gambello and Iglewski, 1991; Fuqua and Greenberg, 2002).

FIGURE 52.4 Petri plates inoculated with luminous bacteria, photographed in daylight (left) and by their own light (right) Note non-luminous colony among the cluster of four in the centre of the plate. (Photograph by author.)

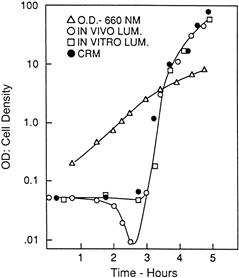

The basic observation was that in newly inoculated cultures of a luminescent marine bacterium, Vibrio fischeri, the onset of exponential growth occurs without a lag but luminescence does not increase until mid-logarithmic phase, when transcription of the lux operon is triggered and light emission literally shoots up, doubling every four minutes or so (Fig. 52.5). This was shown to be due to an inducer of luciferase synthesis produced by the bacteria themselves, which was therefore dubbed the autoinducer. Its structure was found to be a homoserine lactone (Eberhard et al., 1981); other molecules serve the same role in other species and groups (Schaefer et al., 2008; Ng and Bassler, 2009).

FIGURE 52.5 Autoinduction (quorum sensing) in luminous bacteria. Cells inoculated at a cell density of about 0.1 (660 nm) grow exponentially, but the luciferase remains constant for the first 3 hours, after which it rises steeply, attributable to the accumulation of autoinducer in the medium.

The ecological implications are evident: in planktonic bacteria free-living in the ocean, autoinducer cannot accumulate, so no luciferase synthesis occurs. This makes sense; the open ocean is a habitat where the luminescence of a lone bacterium presumably has no value, whereas it evidently does in a light organ with a trillion others (Parsek and Greenberg, 2005). There, high autoinducer levels are readily reached, so the luminescence genes are transcribed. Many considered this as something special in luminous bacteria until the 1990s, when it was discovered that genes controlling autoinduction occur in many different bacteria, controlling specific genes having similarly evident functional importance (Gambello and Iglewski, 1991; Fuqua and Greenberg, 2002). For example, genes responsible for toxin production are not transcribed until the population is great enough to overwhelm the infected organism. This led to the adoption of the catchy term “quorum sensing” to refer to this mechanism, even though it does not strictly involve an enumeration mechanism as such.

There are a number of other control mechanisms that serve to regulate the transcription of the lux operon, including glucose (catabolic repression), nutrient levels, iron and oxygen. Each of these factors represents a different mechanism for the physiological control of gene expression and each has implications concerning the ecology of luminous bacteria and the function of their luminescence. But there is also another control: in some species of bacteria, “dark” (very dim) strains arise spontaneously (see Fig. 52.4). In these, the transcription of the luminescent system scarcely occurs, irrespective of conditions, and this is heritable. However, the genes are evidently not lost, for revertants do occur. Thus, by selection for the dark strain, the organism can compete under conditions where luminescence is not advantageous, yet be able to select for luminous forms and populate the appropriate habitat when and where it is encountered. Indeed, the bacterial lux genes may thus occur in many bacterial strains but not be highly expressed. This means that there may be many more potentially luminous bacteria than would be deduced from colonies that are bright on plates.

The possibility that regulation of oxygen supply to bacterial light organs might control light emission has been considered, but there is no strong evidence in support of the idea. However, mechanical shutters, color filters and other optical devices are widespread and important (Morin and Cohen, 1991).

VIB Occurrence and Functions

Planktonic luminous bacteria occur ubiquitously in the oceans and can be isolated from sea-water samples anywhere in the world, from the surface to depths of 100 m or more. A primary habitat where most species abound is in association with a higher organism or solid substrate, as commensals, parasites or symbionts, where growth and propagation occur. Planktonic forms are ubitquitous, but do not grow significantly, as sea water is a poor medium; their occurrence there is attributed to the overflow from primary habitats (Nealson and Hastings, 1991).

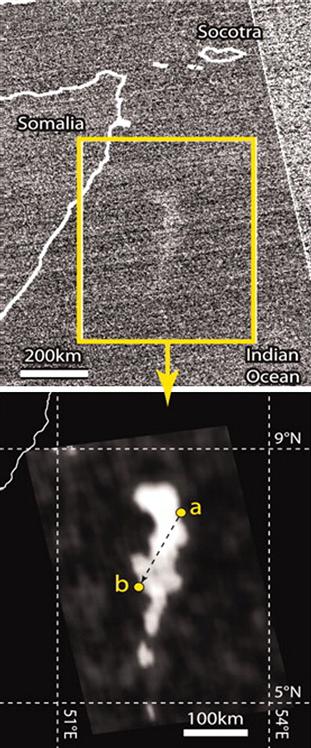

But there are displays in the ocean attributed to bacteria, the so-called “Milky Seas”, which have been reported repeatedly over the centuries in logs of merchant ships and accurately described in Verne’s “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea”. The phenomenon was recently visualized by satellite imaging (Miller et al., 2005; Nealson and Hastings, 2006), recorded as a continuous night-time luminescence in the ocean off the Horn of Africa covering an area the size of the state of Connecticut, persisting for three nights (Fig. 52.6). It is believed that it is due to bacteria, indicated by the fact that the light is continuous. But this flies in the face of the fact that in all studied luminous bacteria, including ‘‘free-living’’ planktonic forms, regulation has been shown to involve quorum sensing, described above, and sea water should not have the requisite free-living bacterial concentration for autoinducer to accumulate. So, if bacteria are responsible, they may be growing on (possibly decomposing) microfilamentous algae, where autoinducer could accumulate. The isolation of the bacteria responsible and well-designed on-site studies of the phenomenon should be carried out.

FIGURE 52.6 Raw (top) and digitally enhanced (bottom) images of a “milky sea” on January 25, 1995 detected by satellite-based camera. The land area at the left is the Horn of Africa in Somalia. The points of entry and exit of the ship from the luminous area, as reported in the log of the S.S. Lima, are points a and b in the enhanced image. Scale bars as shown. (By permission, Steve Miller and Steve Haddock.)

The most exotic and specific habitats of luminous bacteria are specialized light organs (e.g. in fish and squid) in which a pure culture is maintained at a high density and at high light intensity, as in the flashlight fish. In teleosts, some 11 different groups carrying such bacteria are known. In such associations, the bacteria receive a niche and nutrients, while the host receives the benefit of the light and may use it for one or more specific purposes, such as for concealing the silhouette. Many aspects of how such symbioses are achieved – the initial infection, exclusion of contaminants, nutrient supply, restriction of growth but bright light emission – are not fully understood (Hastings et al., 1987). But recent studies (Chun et al., 2008) in the bobtail squid have resulted in many new findings over the past decade, including the demonstration that rhodopsin is expressed in the light organ cells, suggesting the presence of extraretinal photoreceptors.

Intestinal bacteria in marine animals, notably fish, are often luminous, and heavy pigmentation of the gut tract is sometimes present, presumably to prevent the light from betraying the location of the fish to predators. Luminous bacteria growing on a substrate, be it a parasitized crustacean, the flesh of a dead fish, or a fecal pellet, can produce a light bright enough to attract other organisms to feed on the material. It has recently been shown by video recording that a fish will selectively feed in total darkness on prey baited with luminous bacteria but completely ignore non-baited prey (M. Zarubin and S. Belkin, personal communication).

The only known terrestrial luminous bacteria are those harbored as symbionts by nematodes, which are parasitic on insects such as caterpillars. The nematode carries the bacteria as symbionts and injects them into the host where they release fertilized eggs. The bacteria grow and the developing nematode larvae feed on them. The dead but now luminous caterpillar (Fig. 52.7) attracts scavengers, which disperse the nematode offspring, along with the bacteria.

FIGURE 52.7 Caterpillar luminescence due to parasitic luminous bacteria.

VIC Biochemistry

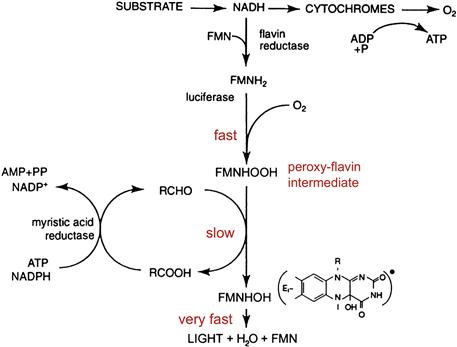

Luminous bacteria typically emit continuous light peaking at ≈490 nm. When strongly expressed, a single bacterium may emit ≈104–105 photons/s. The system is biochemically unique and is diagnostic for a bacterial involvement in the luminescence of a higher organism; in some, but not all cases, they can be isolated and grown in the laboratory. (Some symbionts have not been cultured.) The biochemical pathway itself (Fig. 52.8) constitutes a shunt of cellular electron transport at the level of flavin and reduced flavin mononucleotide is the substrate (luciferin) that reacts with oxygen in the presence of bacterial luciferase to produce an intermediate peroxy flavin (Hastings et al., 1985; Baldwin and Ziegler, 1992).

FIGURE 52.8 The luciferase reaction in bacteria. In the electron transport pathway, luciferase shunts electrons at the level of reduced flavin (FMNH2) directly to molecular oxygen. In the next step with long-chain aldehyde, hydroxy FMN is produced in its excited state (∗) along with long-chain acid. The FMN product is reduced again and recycles; the aldehyde is also regenerated enzymatically.

This intermediate then reacts with myristic aldehyde to form the acid and the luciferase-bound hydroxy flavin in its excited state. Although there are two substrates in this case, the flavin can claim the name luciferin on etymological grounds, since it forms (bears) the emitter. The bioluminescence quantum yield has been estimated to be about 30%. There are enzyme systems that serve to maintain the supply of aldehyde, and genes coding for these enzymes are part of the lux operon, along with autoinducer and others (Meighen, 1991).

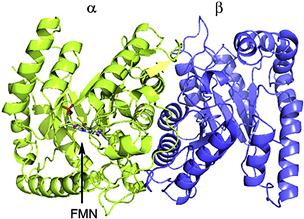

The luciferase and the mechanism of the bacterial reaction have been studied in great detail and its crystal structure is known (Fisher et al., 1996). The enzyme is an external flavin monoxygenase (EC #1.14.14.3), a heterodimeric (α-β) protein (≈80 kDa) in all species, with homology to long chain alkane monooxygenases (Li et al., 2008). Structurally, they appear to be relatively simple: no metals, disulfide bonds, prosthetic groups or non-amino acid residues are involved. The subunits are similar but possess only a single active center per dimer, located on the α subunit. A recent structure crystallized with FMN shows the site of its binding as well as insight concerning the way in the β subunit stabilizes the protein (Fig. 52.9) (Campbell et al., 2009). Curiously, none of other homologous enzymes of this type have been found to emit light, even at very low quantum yields.

FIGURE 52.9 The crystal structure of FMN-bound bacterial luciferase, showing the α subunit (left, green) and β subunit (right, purple), as well as the site of the bound FMN. (By permission of authors and publisher, Amer Chem Soc.)

An interesting feature of this luciferase reaction is its inherent slowness: at 20°C, the time required for a single catalytic cycle is about 20 s. The luciferase peroxy flavin itself has a long lifetime; at low temperatures (−20°C) it has been isolated, purified and characterized, but not crystallized. It can be further stabilized by aldehyde analogs such as long-chain alcohols and amines, which bind at the aldehyde site.

VII Dinoflagellate Luminescence

VIIA Regulation by pH and a Circadian Clock

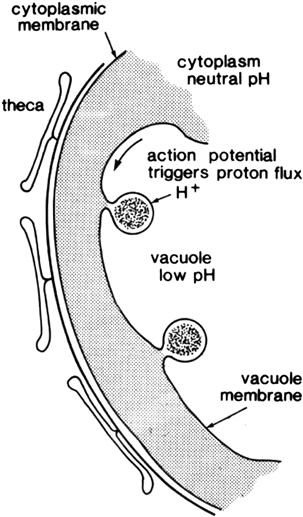

Dinoflagellate flashes are brief (≈100 ms), triggered by membrane action potentials, typically initiated mechanically, that sweep around the cell, as determined in the giant heterotrophic species, Noctiluca (Eckert, 1965). The active membrane surrounding the cell vacuole is the tonoplast and, while the character of the action potential has not been definitely established, it was postulated some years ago (Fogel and Hastings, 1972) that voltage-gated proton channels allow protons from the vacuole to enter the many small membrane-enveloped luminous organelles, called scintillons (Fig. 52.10), initiating the highly pH dependent reaction. The presence of voltage-gated proton channels in a dinoflagellate has recently been demonstrated (Smith et al., 2011).

FIGURE 52.10 Fluorescence images of dinoflagellate cells (Lingulodinium polyedrum) at night (left) and during day phase (right), showing many luminous organelles (scintillons) at night and very few by day. The red background is fluorescence of the abundant chlorophyll.

Neither quorum sensing nor the composition of the medium affect the development and expression of bioluminescence in dinoflagellates. But, on a far different time scale, luminescence in L. polyedrum and some other dinoflagellates is regulated by day–night light–dark cycles and an internal circadian biological clock mechanism (Morse et al., 1990; Hastings, 2007). Scintillons are numerous during the night phase but much less so by day (see Fig. 52.10) and both flashes and glow are greater then. The regulation is attributed to an endogenous mechanism; cultures maintained under constant conditions (light, temperature) continue to exhibit rhythmicity for many days, but with a period that is not exactly 24 hours: it is only about one day (=circa-diem).

The basic mechanism of circadian clocks appears to differ in different groups (Loras and Dunlap, 2001; Johnson et al., 2008; Mehra et al., 2009; Qin et al., 2010. Regulation of luminescence in the dinoflagellate L. polyedrum has been found to involve a daily de novo synthesis and destruction of specific proteins, translationally controlled by a still-unknown mechanism. This appears to differ from all other systems, both bacterial and animal, and remains an enigma. In humans and other higher animals, where it regulates the sleep–wake cycle and many other physiological processes, the mechanism involves the nervous system and transcriptional regulation.

VIIB Occurrence and Function

Dinoflagellates occur ubiquitously in the oceans as planktonic forms and contribute substantially to the so-called “phosphorescence” commonly seen at night in summer when the water is disturbed. They occur abundantly in surface waters and most species are also photosynthetic; some produce neurotoxins (e.g. saxitoxin), which can accumulate in shellfish and constitute a health hazard. In the phosphorescent bays (e.g. in Puerto Rico and Jamaica), high densities of a single species (Pyrodinium bahamense) typically occur. The so-called red tides, which occur world-wide and may cause fish kills due to toxins or oxygen deprivation, are blooms of dinoflagellates, sometimes a luminous species. At night during such red tides, one can see waves breaking or the undulating luminescent pattern left behind by fish fleeing as the boat approaches. World War II aviators based on aircraft carriers in the South Pacific tell of the ease with which they relocated their base ship after a night mission – or equally well a target ship: a luminescent wake may extend for many kilometers behind a ship as the persistent turbulence stimulates the cells to emit light.

About 6% of all dinoflagellate genera contain luminous species, all marine. As a group, dinoflagellates are important as symbionts, notably for contributing photosynthesis and carbon fixation in animals but, unlike bacteria, no luminous dinoflagellates are known from symbiotic niches.

VIIC Biochemistry and Cell Biology

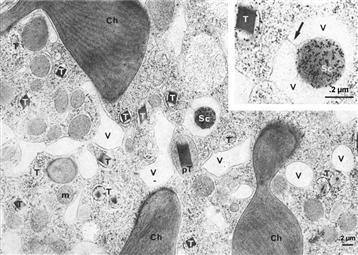

As mentioned above, luminescence in dinoflagellates is emitted from scintillons, many small (≈0.5 μm), novel cortical organelles. They occur as outpocketings of the cytoplasm into the cell vacuole, like a balloon, with the neck remaining connected, as shown in electron micrographs labeled with antiluciferase-labeled gold particles (Fig. 52.11) (Nicolas et al., 1987), diagrammatically represented in Fig. 52.12. They can also be visualized by immunolabeling with fluorescent antibodies raised against the luminescence proteins (Fritz et al., 1990), in vivo by their bioluminescence (Johnson et al., 1985), as well as by the fluorescence of luciferin (see Fig. 52.10). Dinoflagellate luciferin is a novel tetrapyrrole related to chlorophyll (Nakamura et al., 1989). Lase and LBP are the only major proteins in scintillons, other cytoplasmic components being somehow excluded.

FIGURE 52.11 Immunoelectron microscopy of Lingulodinium polyedrum. Gold labeled anti-luciferase marks a scintillon (Sc) hanging in a vacuole (V). Ch, chloroplast; M, mitochondrion; T, trichocyst; pT, pre-trichocyst.

FIGURE 52.12 Scintillons of dinoflagellates represented as organelles formed as cytoplasmic outpocketings hanging in the vacuole.

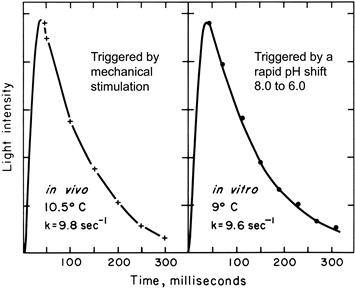

Activity can be obtained in extracts made at pH 8 simply by shifting the pH from 8 to 6; it occurs in both soluble and particulate fractions; both activities peak at pH 6. The existence of activity in both soluble and particulate (scintillon) fractions indicates that during extraction some scintillons are lysed, while others seal off at the neck and form closed vesicles, which have been purified and characterized. The in vitro activity occurs as a flash (≈200 ms, 10°C), very similar to that of the living cell (Fig. 52.13) and the kinetics are independent of the dilution of the suspension. For the soluble fraction, the kinetics does depend on dilution, as enzyme concentration differs.

FIGURE 52.13 Kinetics of flashes of a living cell (left) and of isolated scintillons (right).

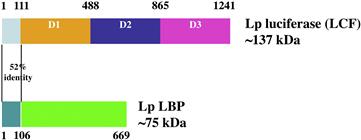

The Lase is unique in having three catalytic highly similar sequences, called domains, in a single molecule (Mr, ≈140 kDa). Each domain, when expressed and assayed individually, has activity and the sequences of the central 166 amino acid of the three (>95% identical) constitute the catalytic sites (Fig. 52.14) (Li et al., 1997). The luciferin is bound to LBP (Mr, ≈73 kDa), which also has domains, but four, and less well conserved. Both proteins occur in the genome in many tandem copies and the N-terminal 106 amino acids of the two are ≈50% identical, but the function of that region remain unknown.

FIGURE 52.14 Organization of the two scintillon proteins in the bioluminescence of Lingulodinium polyedrum. The N-terminal regions of the two are similar, but its function is not known. The three domains of luciferase (LCF, upper) are similar and each has catalytic activity alone; the luciferin binding protein (LBP, lower) has four domains with significant but not great similarity.

In solution, both activities are pH dependent with pKs at 6.7; at pH 8, the LBP binds luciferin and Lase is inactive; at pH 6 luciferin is not bound and Lase is active. As shown by site directed mutagenesis, the pH dependence of Lase is due to four histidines located in the N-terminal region of each domain; if substituted by alanines, the luciferase is fully active at pH 8 (Li et al., 2001).

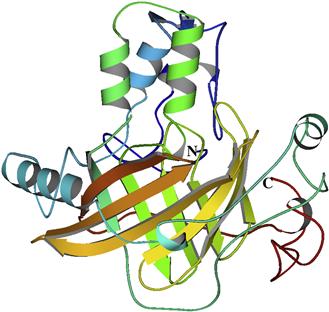

These Lase features can be visualized in the crystal structure of its domain 3 (Fig. 52.15) (Schultz et al., 2005). A major part forms a barrel, inside of which is the luciferin binding site; three alpha helices form a channel but, at pH 8, it is too small for luciferin to enter. The four histidines responsible for the pH-dependent change are located in these sequences; molecular dynamics calculations indicate that when the histidines are protonated or substituted by alanines a conformation change would lead to an opened channel.

FIGURE 52.15 A ribbon diagram of the crystal structure of Lingulodinium luciferase domain 3. The lower barrel structure, where the active site is located, is composed of 10 anti-parallel β-strands. The upper α-helices (green and blue) regulate the opening of a channel for the entry of luciferin.

The presence of repeated conserved sequences in one enzyme molecule is not unprecedented but, to our knowledge, this is the only case in which each of the sequences has been shown to be separately active. A possible reason for the presence of three active sites on a single molecule is that it allows activity to be greater without an increase in the colloidal osmotic pressure of the scintillon.

VIII Coelenterates and Ctenophores

VIIIA Regulation by Ca2+

Early attempts to isolate biochemically and identify active fractions of the luminous jellyfish Aequorea were frustrated, even though cell-free extracts exhibited strong light emission lasting an hour or longer. The clue, as once told by Shimomura (personal communication), came when he discarded a still-emitting extract in the sink and noticed that it became much brighter. Tracing this to calcium, he extracted the cells in the presence of EDTA to chelate calcium and discovered that the activity was retained in a single protein, which he named aequorin and dubbed a photoprotein (Shimomura et al., 1962). While at the time he considered photoprotein to be an altogether new type of bioluminescence system, it turned out that it is indeed a luciferin–luciferase type system and that aequorin is a reaction intermediate in which the luciferin bound to the luciferase (apoaequorin) has already reacted with oxygen to form a (very) stable peroxide, as confirmed by crystal structures. While aequorin is analogous in some respects to the bacterial flavin–peroxy intermediate, the latter is far less stable and has not been crystallized or its structure determined.

Aequorin is stored in photocytes; an action potential mobilizes Ca2+, which reacts with aequorin and causes the reaction to go to completion, with the formation of luciferase-bound excited oxidized luciferin and then light emission.

VIIIB Occurrence and Function

Luminescence is common and widely distributed in ctenophores and coelenterates (Cormier in Herring, 1978; Herring in Herring, 1978), but absent in sea anemones and corals. In the ctenophores (comb jellies), luminous forms comprise over half of all genera, whereas in the coelenterates (cnidaria), it is about 6%. Luminous hydroids, siphonophores, sea pens and jellyfish, among others, are well known. The organisms are mostly sessile or sedentary and, upon stimulation, emit light as flashes. In some groups the luminescence is secreted.

Hydroids occur as plant-like growths, typically adhering to rocks below low tide level in the ocean. Upon touching them there is a sparkling emission conducted along the colony; repetitive waves from the origin may occur. Luminous jellyfish (hydromedusae such as Aequorea aequorea and Pelagia noctiluca) are well known; the bright flashing comes from photocytes along the edge of the umbrella at the base of the tentacles. Aequorea occurs during the summer in the ocean off the northwest USA. The sea pansy, Renilla, which occurs near shore on sandy bottoms, has also figured importantly in the elucidation of the biochemistry of coelenterate luminescence (Cormier, 1981).

Photocytes occur as specialized cells located singly or in clusters in the endoderm. They are commonly controlled by epithelial conduction in hydropolyps and siphonophores and by a colonial nerve net in anthozoans. The light may be emitted as one or many flashes per stimulus. The putative neurotransmitter involved in neural control of luminescence in Renilla is adrenaline or a related catecholamine.

VIIIC Biochemistry and Cell Biology

The luciferin of coelenterates, coelenterazine, is notable for its widespread phylogenetic distribution, speculated to serve in non-luminous organisms as an antioxidant. Actually, the jellyfish Aequorea obtains coelenterazine from its diet (Haddock et al., 2001), so it is analogous to a vitamin, except for the fact that light emission is not necessary for life. In some cases (e.g. Renilla), the sulfated form of luciferin may occur as a precursor or storage form and is convertible to active luciferin by sulfate removal with the co-factor 3′5′-diphosphadenosine. The active form may also be sequestered by a Ca2+ sensitive binding protein, analogous to the dinoflagellate binding protein. In this case Ca2+ triggers the release of luciferin and then flashing, thus different from the Aequorea mechanism.

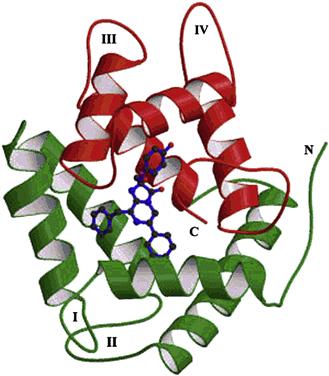

As described above, in Aequorea, Obelia and other hydromedusae, the luciferin and luciferase (EC#1.13.12.5) react with oxygen to form a stable peroxide (aequorin or obelin); stored in photocytes, it remains poised for the completion of the reaction (Blinks et al., 1982; Charbonneau et al., 1985; Cormier et al., 1989; Shimomura, 2006). The crystal structure of this intermediate (Fig. 52.16) has been determined for both Aequorea and Obelia (Head et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2000). An action potential allows Ca2+ to enter and bind to the protein, shifting or breaking hydrogen bonds, thus changing its conformational state and allowing the reaction to continue, but without the need for free oxygen at this stage. An enzyme-bound cyclic peroxide, a dioxetanone, is a postulated intermediate; it breaks down with the formation of excited coelenteramide, the emitter, along with a molecule of CO2. The enzyme itself, called apoaequorin, can react again with coelenterazine and oxygen to form aequorin anew; it is homologous with calmodulin (Lorenz et al., 1991).

FIGURE 52.16 Structure of the calcium-regulated photoprotein obelin. The N-terminal α-helices are green (lower) and the C-terminal red (upper). The hydroperoxycoelenterazine substrate is the blue stick representation buried between green and red α-helices. (By permission John Lee.)

It had been reported in the early literature that coelenterates could emit bioluminescence even if fully deprived of oxygen. The explanation is now evident: aequorin is an intermediate in which the substrate has already reacted with oxygen and the cells store it in a stable state; only calcium is needed to emit light.

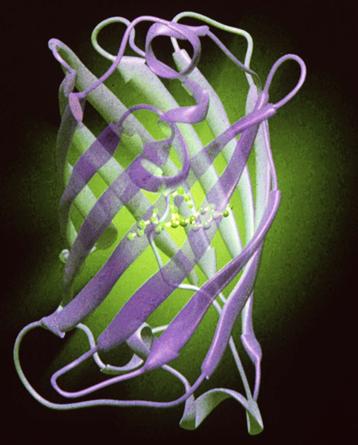

Remarkably, in vitro, the light emitted from this isolated system is blue, with a broad spectrum peaking at ≈480 nm while, in vivo, the emission is green (λmax = 508 nm) and its spectrum is narrow. This is due to a different protein with a second chromophore, green fluorescent protein (GFP), which is the emitter. Some years earlier, it had been observed that the photocytes of Aequorea exhibited a green fluorescence, corresponding to the color of their bioluminescence. Johnson et al. (1962) observed the blue of the in vitro system along with a green fluorescence in extracts and suggested that it might be responsible by absorption and re-emission. Morin and Hastings (1971) observed that isolated photocytes triggered to emit by Ca2+ emitted green light whereas, if lysed before Ca2+ addition, the emission was blue, and proposed that this is due to radiationless (Foerster-type) energy transfer to the green fluorescent protein (GFP). This protein, whose chromophore is formed by the slow (≈1 hour, oxygen required) post-translational modification of three centrally located amino acids (Cody et al., 1993), thus covalently attached, is now widely used as a fluorescent marker or reporter gene (see Applications). Its crystal structure (Fig. 52.17) reveals a fascinating lantern-like structure (Ormö et al., 1996; Yang et al., 1996).

FIGURE 52.17 Crystal structure of GFP showing the chromophore in the center.

The overall reaction is thus:

More recently, it was discovered that similar proteins occur in a variety of colors in other coelenterates, including corals, not associated with bioluminescence; their use as reporters has been evaluated (Baird et al., 2000) and color mutant GFPs have provided an array of colors that greatly expand the possible applications (Zhang et al., 2002).

Some strains of luminous bacteria also utilize an accessory protein, whereby the color may be either blue- or red-shifted, depending on the fluorophore which, however, is not covalently attached, so not suitable as a label. It has also been determined that the color shift is not attributable to Foerster-type energy transfer in this case; the protein participates in the luciferase reaction itself (Eckstein et al., 1990).

IX Firefly Luminescence

IXA Regulation by a Nerve Impulse and Oxygen

The firefly light organ comprises a series of photocytes arranged in a rosette, positioned radially around a central trachea, which supplies oxygen to the organ via tracheoles (Smith, 1963). The organ itself comprises a series of such rosettes, stacked side-by-side in many dorsoventral columns. Photocyte granules or organelles containing luciferase have been identified with peroxisomes on the basis of immunochemical labeling.

The control of firefly flashing has long intrigued scientists and while there is agreement that it is ultimately controlled by regulating oxygen in the photocytes, the mechanism remains controversial. It is triggered in the first instance by a nerve impulse via the ventral nerve cord (Case and Strause in Herring, 1978); however, the nerves do not terminate on the photocyte, but on adjacent tracheal end cells, which surround the tracheoles entering the photocytes. The transmitter is octopamine and it takes some 50 ms or longer after the arrival of the nerve impulse for the onset of the flash to occur. Thus, the flash is not triggered directly by an action potential. Nor are any of the ions typically gated by membrane potential changes (Na+, K+ and Ca2+) likely candidates for controlling luminescence chemistry.

All studies have concluded that the availability of oxygen regulates flashing; there is a strong positive relationship between the extent of the tracheal supply system in the adults of different species and their flashing ability. Also, all assume that photocytes are maintained anaerobic between flashes; the unusually large number of mitochondria buoys the belief. And all, except two recent ones (Trimmer et al., 2001; Ghiradell and Schmidt, 2004), concluded that the onset of the flash is regulated by the entry of oxygen to photocytes and the tracheolar cells were implicated in controlling it. Supporting evidence included the fact that the light organs of larval fireflies, which glow but do not flash, lack the end cells and are directly innervated. Also, firefly lantern tracheoles are reinforced against collapse. Some authors argued that a contractile action of end cells would force air into the photocytes; others proposed that fluid in the tracheoles normally blocks the entry of oxygen and a rapid but transient removal of the fluid, possibly by osmotic means, that allows oxygen to enter and initiate the flash (Timmins et al., 2001). Both were silent on the mechanism responsible for the termination of the flash, but removal of oxygen was tacitly assumed.

A quite different theory was put forward more recently, based on the finding that nitric oxide (NO) can affect the light emission in fireflies (Trimmer et al., 2001). Control of oxygen entry was assumed not to occur; instead it was proposed that oxygen enters continuously and that anaerobiosis is maintained by vigorous and continued mitochondrial respiration, whose inhibition by NO produced in tracheolar cells allows oxygen to enter and react with the luminous organelles. The decline is attributed to its reversal, principally photochemically by the light of the flash itself (Aprille et al., 2004). No follow up or repeats of the studies have appeared.

The second recent proposal is that the cells are indeed maintained anaerobic and that the flash is generated by the release of oxygen from H2O2 within the organelles that emit light, which are modified peroxisomes. No studies in support of the idea have appeared.

The rapid onset and decline characteristic of flashes with precision kinetics seem unlikely to be achieved by an inhibitory-type mechanism. Biochemical evidence suggests that the rate constants are determined by the reaction of oxygen with enzyme bound luciferyl adenylate, which accumulates in a slow reaction in the absence of oxygen (McElroy and Hastings, 1956), analogous to the reaction of aequorin with calcium. The firefly species-specific flash duration would be determined by rate constants, not by the enzyme concentration or the removal of oxygen or variable physiological factors. The formation of new luciferyl-adenylate is slow in relation to the flash, so emission terminates even though some oxygen may remain.

IXB Occurrence, Function

There are only about 100 genera of insects classed as luminous out of a total number of approximately 70 000 (Lloyd in Herring, 1978). But where seen, their luminescence is impressive, most notably in the many species of beetles, the fireflies and their relatives. Fireflies themselves possess ventral light organs on posterior segments, but the South American railroad worm, Phrixothrix, has paired green light organs on the abdominal segments and red ones on the head (Fig. 52.18), while the click and fire beetles, Pyrophorini, have both running lights (dorsal) and landing lights (ventral).

FIGURE 52.18 The railroad worm, with green emitting photophores on each segment and red ones on the head.

The variety of different fireflies, with their different habitats and behaviors, is impressive. The major function of light emission in fireflies is for communication during courtship (Lloyd, 1977, 1980; Case, 1984) and the different flashing kinetics and patterns facilitate species identification. In North American species, a female on the grass or a leaf emits a query flash, while a male responds with a species-specific time delay. Flash flickering occurs in some species, sometimes at frequencies higher than detectable by the human eye (≈40 Hz).

The signal mechanism in the synchronously flashing fireflies in Southeast Asia (Pteroptyx spp.) is not so well understood. These form congregations of many thousands in single trees, where the males produce an all-night-long display, with flashes every 1–4 s, dependent on species (Buck, 1988), which may serve to attract females to the tree.

The cave glow worm Arachnocampa (a fly) exudes beaded strings of slime from its ceiling perch (Fig. 52.19), which glisten in the reflected light from its caudal light organ and serve to entrap small flying prey that are attracted by the “fishing lines” (Fig. 52.20). While it is similar in some respects to its much less impressive American relative Orfelia, the two differ biochemically (Viviani et al., 2002).

FIGURE 52.19 Luminous dipteran larvae (Arachnocampa) on the ceiling of a cave in New Zealand.

FIGURE 52.20 “Fishing lines” produced by Arachnocampa as traps for flying insects that wander into the cave.

IXC Biochemistry and Cell Biology

The firefly system was the first in which the biochemistry was extensively studied. It had been known since before 1900 that cell-free extracts could continue to emit light for several hours or longer, and that after the complete decay of the light, emission could be restored by adding a second extract prepared with hot water (then cooled). The enzyme luciferase was assumed to be in the first, with all the luciferin substrate being used up during the emission, and luciferin in the second, since the enzyme was denatured by the hot-water extraction. This was named the luciferin–luciferase reaction by DuBois in 1885, and it was already known in the first part of the 20th century that luciferins and luciferases from the different major phyla would not cross react, indicative of their independent evolutionary origins (Harvey, 1952).

In 1947, it was discovered that the addition of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) alone to an “exhausted” cold water extract, resulted in an enormous bioluminescence response (McElroy, 1947). This response suggested that luciferin had not actually been used up in the cold water extract; but ATP could not be the emitter, since it does not have the appropriate fluorescence. For some time, ATP was thought to be providing the energy for light emission. But, as noted earlier, the energy available from ATP hydrolysis is only about 7 kcal per mole, whereas the energy of a visible photon is ≈50 kcal per mole. It was soon discovered that firefly luciferin, which was shown to be a unique benzothiazole, was still present in large amounts in the “exhausted” cold water extract, and that it was ATP that was used up (by ATPases in crude extracts), but available in the hot water extract. ATP was later shown to be required to form the luciferyl adenylate intermediate which, in a separate step, then reacts with oxygen to form a cyclic luciferyl peroxy species, which breaks down to yield CO2 and an excited state of the carbonyl product (McElroy and DeLuca in Herring, 1978).

In in vitro reactions in which luminescence has decreased to a low level (emission may continue for days), it was found that emission is greatly increased by coenzyme A, but the reason for this was obscure. The recent discovery that long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (EC# 6.2.1.3) has homologies with firefly luciferase (EC# 1.13.12.7) both explains this observation (Fraga, 2008) and indicates the evolutionary origin of the gene.

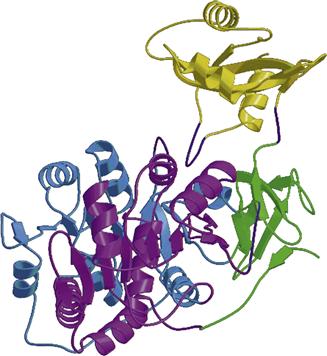

Firefly luciferase catalyzes both the luciferin activation and the subsequent oxygen reaction leading to the excited product. The crystal structure (Fig. 52.21) revealed the structural basis for the two-step reaction and confirmed that the same protein is responsible for both (Conti et al., 1996). Luciferase has been cloned and expressed in other organisms, including E. coli and tobacco. For activity, luciferin must be added exogenously; tobacco “lights up” with the roots dipped in a luciferin solution (Ow et al., 1986). There are some beetles in which the light from different organs is a different color, shown to be due to the luciferase not the luciferin. The same ATP-dependent luciferase reaction with the same luciferin occurs in the different organs, but the luciferases are slightly different, coded by different (but homologous) genes (Wood et al., 1989; Viviani et al., 2006; Branchini et al., 2007; Viviani, 2009). They are presumed to differ with regard to the conformation of the site that binds the excited state, which thereby alters the emission wavelength.

FIGURE 52.21 Ribbon diagram of the firefly luciferase (Luc) structure. The large N-terminal domain (amino acids 1–436) is connected to the smaller C-terminal domain (amino acids 440–550 shown in yellow) through a short hinge peptide. (Reproduction permission from Nature Publishing Group.)

X Other Organisms: Other Chemistries

The four systems described above are known best, but several others have been studied in some detail, revealing interesting differences in both physiological and biochemical aspects.

XA Molluscs

Snails (gastropods), clams (bivalves) and cephalopods (squid) all have bioluminescent members (Young and Bennett, 1988). The squid luminous systems are by far the most numerous, and also diverse, both in form and function, rivaling the fishes in these respects, and some produce brilliant displays (Fig. 52.22). As for fish, some squid utilize symbiotic luminous bacteria, but others are self-luminous, indicating that bioluminescence had more than one evolutionary origin within the classes.

FIGURE 52.22 Firefly squid (Watasenia) in aquarium tank with onlookers.

Also like some fish, some squid possess photophores, which may be used in spawning and other interspecific displays (communication). Photophores are compound structures with associated optical elements, such as pigment screens, chromatophores, reflectors, lenses and light guides. They may emit different colors of light and are variously located near the eyeball, on tentacles, body integument or associated with the ink sac or other viscera. An octopus with luminescent suckers has been reported (Johnsen et al., 1999). In some species, luminescence intensity has shown to be regulated in response to changes in ambient light, indicative of a camouflage function.

Along the coasts of Europe, there is a clam, Pholas dactylus, which inhabits chambers that it makes by boring holes into the soft rock. When irritated, these animals produce a bright cellular luminous secretion, squirted out through the siphon as a blue cloud. This animal and its luminescence has been known since Roman times, and the system was used by DuBois in his discovery and description of the “luciferin–luciferase” reaction in the 1880s (see above). Well ensconced in its rocky enclosure, the animal presumably uses the luminescence somehow to thwart would-be predators.

The Pholas reaction has been studied extensively; the luciferin, now called pholasin, has a protein-bound chromophore; it is probably dehydrocoelenterazine. The luciferase is a copper-containing large (>300 kDa) glycoprotein (Hentry et al., 1975). It can serve as a peroxidase with several alternative substrates, suggesting the involvement of a peroxide in the light emitting pathway; the superoxide ion may be involved in the reaction.

There are luminous species in several families of gastropods; a New Zealand pulmonate limpet, Latia neritoides, is notable as the only known luminous organism that can be classed as a truly fresh-water species. It also secretes a bright luminous slime (green emission, λmax = 535 nm), whose function may be to forewarn predators. Its luciferin is an enol formate of an aldehyde, but the emitter and products in the reaction are unknown; in addition to its luciferase (MW ≈170 kDa; EC#1.14.99.21), a “purple protein” (MW ≈40 KDa) is also required, but only in catalytic quantities, suggesting that it may be somehow involved as a recycling emitter.

XB Annelids

The annelids also include numerous luminous species, both marine and terrestrial (Herring in Herring 1978). The marine polychaete Chaetopterus constructs and lives in buried U-shaped tubes with only the openings at the surface of the sea floor; they pump sea water through the tube and exude luminescence upon stimulation, but the chemistry of the reaction has completely eluded researchers. The function of its emission may be similar to that of Pholas. Other marine polychaetes include the Syllidae, such as the Bermuda fireworm, and the polynoid scale worms, which shed their luminous scales as decoys. Both have largely escaped biochemical elucidation, although extracts of the latter have been shown to emit light upon the addition of superoxide ion.

More but still limited knowledge is available concerning the biochemistry of the reaction in terrestrial earthworms, some of which are quite large, over 60 cm in length (Wampler, 1981). Upon stimulation they exude celomic fluid from the mouth, anus and body pores. This exudate contains cells that lyse to produce a luminous mucus, emitting in the blue-green region. In Diplocardia longa, the cells responsible for emission have been isolated; luminescence in extracts involves a copper-containing luciferase (MW ≈300 kDa) and the luciferin (N-isovaleryl-3 amino- 1 propanal). The in vitro reaction requires H2O2, not free O2. The exudate from animals deprived of oxygen does not emit, but will do so after the admission of molecular oxygen to the free exudate.

XC Crustaceans

Many crustaceans are luminescent (Herring, 1985b). The cypridinid ostracods, such as Vargula (formerly Cypridina) hilgendorfii, are small organisms that possess two glands with nozzles from which the luciferin and luciferase (EC#1.13.12.6) are squirted into the sea water, where they react and produce a spot of light that retains its integrity, useful either as a decoy or for communication.

Cypridinid luciferin and its reaction have differences and similarities to the coelenterazine system (Cormier in Herring, 1978). The luciferin in both is a substituted imidazopyrazine nucleus that reacts with oxygen to form an intermediate cyclic peroxide, which then breaks down to yield CO2 and an excited carbonyl. However, the cypridinid luciferase gene has been cloned and appears to have no homologies with the gene for the corresponding coelenterate proteins and calcium is not involved in the cypridinid reaction. The two different luciferases reacting with similar luciferins have apparently had independent evolutionary origins, indicative of convergent evolution at the molecular level.

Euphausiid shrimp possess compound photophores with accessory optical structures and emit a blue ventrally-directed luminescence. The system is unusual because both luciferase and luciferin cross-react with the dinoflagellate system. This cross-taxon similarity indicates another possible exception to the rule that luminescence in distantly related groups had independent evolutionary origins, thus another case of convergent evolution. The shrimp might obtain luciferin nutritionally, but the explanation for the occurrence of functionally similar proteins is not evident. One possibility is lateral gene transfer; convergent evolution is another. The sequence of the shrimp luciferase has not been determined.

XD Fishes

Bioluminescence in fishes is highly diverse and occurs in both teleost (bony) and elasmobranch (cartilaginous) fishes. Partly because the animals have not been so readily available, relatively little is known about their physiology and biochemistry, but many have been described from specimens (Herring, 1982).

As already noted, many fish obtain their light emitting ability by culturing luminous bacteria in special organs. Many coastal and deep-sea luminous fishes fall into this category, while others are self-luminous. Those include Porichthys, the midshipman fish, so-called because of the array of photophores distributed linearly along the lateral lines, like buttons on a military uniform. It has been the object of considerable study and more is known about the physiological control of luminescence in it than in any other fish. Its luciferin and luciferase cross-react with the ostracod (cypridinid) crustacean system described above. This cross-reactivity was an enigma until it was discovered that Puget Sound fish have photophores but are unable to luminesce, but can do so if the animals are injected with or fed cypridinid luciferin. This observation showed that luciferin may be obtained nutritionally. Did the luciferase in this fish originate independently making use of the available substrate, or was the ability to synthesize luciferin lost secondarily? If the latter, this would be analogous to the loss of the ability to synthesize vitamins in mammals.

Open sea and mid-water species include sharks, some of which may have several thousand small photophores. The teleosts include the gonostomatids, such as Cyclothone, with simple photophores, and the hatchet fishes, having compound photophores with elaborate optical accessories; emission is directed exclusively downwards, indicative of a camouflage function of the light. A number of self-luminous fish eject luminous material; in the searsid fishes this is cellular in nature, but it is not bacterial and its biochemical nature is not known. Such animals may also possess photophores.

Fish often possess different kinds of photophores located on different parts of the body, especially ventrally and around the eyes, evidently with different functions. One interesting arrangement, known in both mid-water squid and myctophids, makes use of a special photophore positioned so as to shine on the eye or on a special photoreceptor. Its intensity parallels that of the other photophores, so it provides information to the animal concerning its own brightness, thus allowing it to match the intensity of its own counterillumination to that of the down-welling ambient light. Another clear case of functional use is in Neoscopelus; in addition to the many photophores on the skin, they also occur on the tongue, allowing it to attract prey to just the right location.

Sexual dimorphism is also frequent in luminescent fish. The appropriately named anglerfishes, with their dangling luminous lures, are the most extreme in this respect (Pietsch, 2009). But males and females of the myctophid, Tarleltonbeania are also very different and were originally thought to be different species. Only one (now known to be the male) has caudal luminous organs and the occurrence of those fish was only known from stomach contents of predator fishes; what turns out to be the female was captured in nets, but never in the company of the male. A proposed explanation is that when a predator attacks, the males dart off in all directions with their dorsal lights flashing, like a police car, leading the predators on a chase (and sometimes getting caught), leaving the females, who remain in place, safe from the predator in the cover of darkness, but easy to catch in a net.

XI Applications of Bioluminescence

In the recent past, the most frequently asked question about bioluminescence was “What is its function, its survival value for the organism?” Bioluminescence was thus viewed mostly as a fascinating feature of the living world, but the study of its physiological and biochemical basis had seemed a most unlikely area of research to contribute in any practical way. It was put in the category of basic research; knowledge for the sake of knowledge: curiosity driven studies, with no predictable applications. Such interests have not faded but, in more recent years, an equally frequent query has concerned the practical applications of research on bioluminescence, reflecting, to be sure, an awareness of the many ways in which science has enabled new advances over the past decades. Thus, speculative paragraphs in grant applications have turned into reality, largely based on advances in molecular biology. Practical applications, both achieved and in progress, have been mind-boggling, rivaling in that respect many other practical developments in biological sciences, ranging from vaccines and test tube babies to drugs, genetic engineering and stem cells.

Actually, analytical applications of bioluminescence have been in use for 50 years. With the discovery of the ATP requirement for light emission in fireflies and the fact that the amount of light is directly proportional to the amount of ATP, many uses emerged. Somewhat later, the isolation of aequorin opened the way for the detection of calcium. Those, and other such measurements of bioluminescence have at least three major advantages over others: (1) rapidity; only a few seconds or minutes are needed; (2) great sensitivity; amounts of substances a billion or more times less than conventional assays can be readily detected; and (3) proportionality over an enormous concentration range; many such assays can be made over a range of one million or more.

The use of firefly luciferase with luciferin added was quickly adopted for the measurement of the amount of ATP in cell and biochemical research. An application with a wider impact was its use in the slaughterhouse, where undetected fecal contamination of animal carcasses has led to sickness and even death from human consumption of the meat products. Detection of bacteria responsible (usually E. coli) was previously done by taking swabs and checking for growth on plates, which takes 24 hours or more; by that time, processing may be complete and the contaminated product on its way to consumers, expensive and hard to track and recall. While the firefly assay is ideal for rapid and sensitive detection of bacteria, such procedures may have a problem; in practice, not all carcasses are sampled so contaminated ones may readily get through, as is known from the fact that contaminated meat continues to be reported from time to time.

The same ATP test is now used for monitoring soft drink production, where mold contamination occurs rarely but unpredictably; all batches are tested, as may be readily done. If discovered only after bottling and distribution to outlets far and wide, it is not only difficult and costly to recall it, the brand may get a poor reputation.

For many years the firefly luciferase used in the ATP tests was purified from fireflies, usually collected by children paid by the number. With the amounts now used this would be impractical or impossible, so recombinant luciferase is used. Today, the greatest demand may be for a new method for rapid determinations of nucleotide sequences of DNA called “pyro” sequencing (Metzker, 2005). The name is based on the fact that pyrophosphate is released in the nucleotide-determination step which, after being converted to ATP, produces a flash of light. With automation about 500 million base pairs can be determined per 10 hour run on a machine.

Concern with water contamination, especially from industry, led to the passage of the “Clean Rivers Act” and to the development of a test to determine the quality of water in rivers and streams. The problem is different from the earlier examples in that the typical contaminants are chemical substances, not living organisms, and different substances in different cases. The method first adopted was empirical; if a fish survived in the water in question for 5 days, the water was judged satisfactory. So a 5-day-long procedure for such an evaluation was developed, typically by sampling downstream from an industrial facility that discharged its waste water. Mobile laboratories, fully equipped with healthy fish in a tank and scientific personnel carried out the determination, traveled week after week from site to site. A team could check only about 50 sites in a year, and it was not cheap!

A curious scientist noted that the light emission from living luminous bacteria was decreased by many different foreign chemical substances and wondered if the light emission might be a proxy for fish survival. The results were positive and the test is now widely used for the determination of water quality both in the USA and many other countries. The success of the method is astonishing and still viewed with some caution; how can it be that the light emission of living bacteria is affected in the same way as a fish by what must be a wide diversity of (and unknown) chemical substances? But it does work!

As described, one of the features of different bioluminescent systems is that they are biochemically different. This means that many different substances can be determined with one luciferase or another, and many such assays have been established. One of the most significant and widely used in research is the jellyfish system, mentioned in the Introduction, where light emission from aequorin requires calcium ion, a substance of key importance in the physiology and regulation of many different processes in living cells, notably muscle and nerve. With the isolation of the jellyfish luciferase gene, the DNA can be inserted directly into individual cells which, with added coelenterazine, produce aequorin and emit light in the presence of calcium in the cytoplasm.

DNA that codes for a luciferase can be attached to the promoter of some target gene, thus serving as a reporter gene for one responsible for the production of some other substance, so when and where the latter is produced can be determined by light emission, all in a non-invasive way – one has only to observe. The expression of a specific gene can be tracked by time, whether it occurs during the day or the night phase, as in circadian control, or time during development. Similarly, the type of cell and location in the body where a specific gene is expressed can be established. Studies are now being carried out by many scientists to locate cancer cells in the body using such methods, with good preliminary results. Another feature: since different luciferase systems may emit light at different wavelengths, different genes can be tagged by different luciferases and their activities followed concurrently in the same cell.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) is a remarkable and now widely used fluorescent protein discovered in the course of studies of bioluminescence (Chalfie et al., 2006; Zimmer, 2010); in addition to the fact that it is non-toxic (based on perhaps some 10 000 published studies), it has three other important features. First, like luciferases and some other genes, it can be used as a reporter by attaching the gene coding for its synthesis to a different promoter; second, the fluorophore is part of the primary sequence of the peptide chain, so does not dissociate even at very low concentrations; and mutant GFPs, in which the color of the fluorescence has been altered by virtue of protein conformation changes, have greatly expanded its applications (Baird et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2002). A drawback is that, like all fluorescent markers, irradiation is required, which itself may have adverse effects on the cell and will always increase the background. But this has not interfered with its widespread use and is now perhaps the most important and widely used of all biological reagents in cell biology; its discovery and application were recognized by the award of a Nobel Prize in 2008 (Chalfie, 2009; Shimomura, 2009; Tsien, 2009).

XII Concluding Remarks

Though relatively rare, the emission of visible light by living organisms occurs in a phylogenetically wide range of species, ranging from bacteria to vertebrates, and has many independent evolutionary origins. The structures of the genes and proteins, as well as the physiological, biochemical and regulatory mechanisms involved, are thus very different. Its functions are also many and diverse, and provide a selective advantage mediated by the detection and responses of other organisms to the light.

The functions of the light may be classed under three major headings: offense, defense and communication, and a fourth to enhance propagation. Light may be used defensively to startle or frighten (flashes), to divert predators, as a decoy or to provide camouflage. Offensively, light may be used as a lure to attract prey. Communication occurs in courtship and mating displays.

An unusual and unexplained fact is that bioluminescence is primarily a marine phenomenon. While there are terrestrial forms, it is virtually absent in fresh water; only one such species is known. It is also not confined to or especially prevalent in animals that live in complete darkness (caves, lakes and the deep ocean).