BERKELEY in the late 1960s was politically seething, and the politics of Telegraph Avenue, and Haight-Ashbury across the bay in San Francisco, were to dominate our two years there. Lyndon Johnson, who might otherwise have been remembered as a great reforming president, was mired in the disaster that was the Vietnam War – inherited from Kennedy. Just about everyone in Berkeley was against the war, and we joined them – in marches in San Francisco, in tear-gassed parades in Berkeley, in demonstrations, classroom disruptions and sit-ins.

I am proud of my part in protesting against American involvement in Vietnam, proud of having worked hard in the anti-war campaign of Senator Eugene McCarthy, less proud of some of the other political movements in which I was involved. The most memorable of these concerned the surreal episode of the ‘People’s Park’ (fictionalized by David Lodge as the ‘People’s Garden’ in his campus novel Changing Places). The People’s Park campaign was an attempt (ultimately successful, as I discovered when I revisited Berkeley on a filming trip recently) to take over for public recreation a piece of waste ground owned by the university and intended for building. With hindsight it was a trumped-up excuse for radical political activism for its own sake, trumped up by anarchist student leaders cynically manipulating the gentle ‘flower-power’ ‘street people’. The radical student leaders and the infamous Governor Ronald Reagan (‘Ronald Duck’ in David Lodge’s novel) gleefully played into each other’s hands, each mining the situation to enhance their following among their respective constituents, and each probably knowing exactly what they were doing. And I, together with most of the younger faculty of the university, played right into their hands. We demonstrated, sat in, ran from the tear gas, wrote outraged letters to the newspapers (my first letter to The Times was on the subject) and cheered as the street people stuck flowers down the rifle barrels of the bewildered and rather scared young National Guardsmen. Honesty compels me to admit a frisson of exhilaration – of which I am now quietly ashamed – at having been tear-gassed and (very slightly) endangered.

I try to peer into my own state of mind in my twenties in Berkeley as honestly as I can. I think what I see there is a kind of youthful excitement at the very idea of rebellion: a Wordsworthian ‘Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive / But to be young was very heaven’. A student called James Rector was shot dead by an Oak-land policeman. It was right to march in protest against that, and with hindsight that seems to have justified, in our minds, our decision to march for the People’s Park in the first place. But of course it didn’t justify it at all, not in itself. The decision to march for the People’s Park required completely separate justification.

We, the younger faculty, convened meetings where we tried to bully our colleagues into cancelling their lectures in solidarity with the activists – and I use the word ‘bully’ advisedly, for I have seen the same thing more recently on the internet in the form of ‘cyberbullying’ by radical activists powerful enough to act as a kind of thought police, just as I saw the same thing at school when willing accomplices would rally around a playground bully. I remember with particular regret a faculty meeting at Berkeley when a decent older professor was reluctant to cancel his lecture and we tried to vote to force him to do so. With remorse I salute his courage, and that of an even older professor whose hand was the sole one raised in support of his colleague’s right to fulfil what he perceived as his duty to give his scheduled lecture. As with Aunty Peggy, as with the Chafyn Grove equivalent, I should have stood up against the bullies. But I didn’t. I was still young, but not all that young. Should have known better.

Mention of radical politics and the street people brings forth a revealing memory, revealing of a sea-change in social mores. I was walking along Telegraph Avenue, axis of Berkeley’s beads-incense-and-marijuana culture. A young man was walking ahead of me, dressed in the insignia of the flower-power generation. Every time a young woman passed him, walking in the opposite direction, he would reach out and tweak one of her breasts. Far from slapping him, or crying ‘Harassment!’, she would simply walk on by as if nothing had happened. And he would proceed to the next one. Today I find this almost impossible to believe, but it is a very secure memory. His demeanour did not appear especially lascivious, and his action was evidently not taken by the young women as the gesture of a male chauvinist pig. It seemed all of a piece with hippiedom, with the laid-back, peace-and-love atmosphere of sixties San Francisco. I am very glad to say that things have changed. Today’s counterparts in age and class of that young man, and the young women he molested (as we should now say), would be among those most strongly outraged at behaviour which was then the norm for that age, class and political persuasion.

In spite of all the politics, I did an adequate job as a junior (indeed, exceptionally young) assistant professor. George Barlow and I shared the lectures on animal behaviour, and I included the ‘selfish gene’ lecture that I had initiated at Oxford. I like to think that the students at Oxford and Berkeley in the late sixties may have been the very first undergraduates in the world to hear of the new ideas that were to become fashionable, in the seventies and thereafter, as ‘sociobiology’ and ‘selfish genery’.

Marian and I were made to feel very welcome at Berkeley, and we made good friends there. As well as George Barlow, these friends included David Bentley the neurophysiologist, Michael Land, now the world’s leading authority on eyes throughout the animal kingdom, and Michael and Barbara MacRoberts, who later came to Oxford as spirited additions to the Bevington Road circle, as did the gently sardonic David Noakes, who was George Barlow’s leading graduate student during my Berkeley years. George hosted a weekly ethology seminar for interested graduate students at his house in the Berkeley Hills, and those evening meetings recaptured for Marian and me something of the wonderful atmosphere of Niko’s Friday evenings at Oxford.

I had never been to America before, and I did find some things bewildering. At my first meeting of the Zoology faculty, everyone spoke almost entirely in numbers. Who’s doing 314? No, I’m doing 246. Nowadays the English-speaking world knows that Xology 101 means (sometimes patronizingly or even derisively) a freshman’s introduction to Xology. But all that numerology was perplexing to me when I first arrived. And who, today, doesn’t understand the verb ‘to major’? But I recall reading an American campus novel and getting a little fed up with the twittering of sophomores and juniors and seniors when, like a breath of fresh air, ‘An English major came into the room.’ Aha, I thought, my mind immediately filled with visions of riding breeches and moustaches, a real character at last.

Marian and I both worked hard at our research. And we talked and talked and talked to each other about our shared scientific interests, on walks in Tilden Park up in the Berkeley Hills, on drives around the beautiful California countryside, at meals, on shopping expeditions over the Bay Bridge to the city of San Francisco, all the time. The atmosphere of our discussions was that of a mutual tutorial, each learning from the other, exploring arguments step by step, moving one step backwards, two steps forwards. The mutual tutorial is something I now strive to achieve in public discussions with colleagues, often filmed for my website or put out on DVDs. Those discussions with Marian were to be the basis of the joint experiments that we did later, after returning to Oxford.

My research at Berkeley was a continuation of my work on chick pecking. My doctoral research had been very Popperian. It made precise predictions about total quantities of choices made in a fixed time. But the model had always begged for more exact observational testing, using precise sequences of pecks as they happened, rather than total numbers of pecks per minute. In Berkeley I turned to the exact sequence, building a new apparatus which, unlike my Oxford one, was capable of recording exactly when each peck happened, rather than just counting pecks per minute. I also increased the peck rate by rewarding each peck with a blast of infra-red heat, which the chicks liked. They were rewarded equally, regardless of which key they pecked, but they still showed colour preferences and they still seemed to be choosing on the basis of the Drive Threshold Model. The pecks were recorded on magnetic tape using a sophisticated and expensive piece of equipment that had been built for George Barlow, known as the Data Acquision System – so called because of a typographical error in the word ‘Acquisition’ on the label.

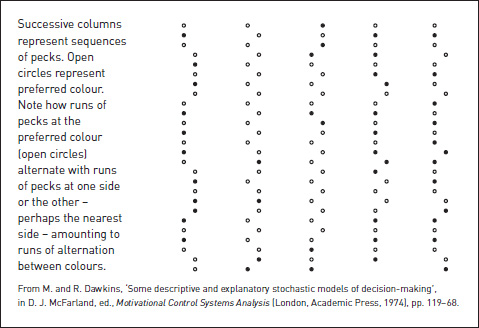

One simple expectation of the Drive Threshold Model is that there should be long runs of pecks at the preferred colour (when the drive was above the threshold for that colour only), interspersed with runs of indifference (when the drive was above two thresholds). There should never be significant runs of pecks at the less preferred colour. Following the Attention Threshold Model, I expected that indifference to colour really meant preference for one side. Since the apparatus was programmed to present each colour to alternate sides, changing after every peck (with occasional random variations), I predicted sequences such as you see in the following picture, which represents real data from one particular experiment, and seems to confirm the prediction very nicely.

Of course, this picture is no more than an anecdote, one out of many experiments. I did statistical analyses to substantiate this prediction and several other predictions, using data from large numbers of experiments. The predictions of the Attention Threshold version of the Drive Threshold Model were upheld.

Some time during our second year at Berkeley, Marian and I were visited by Niko and Lies Tinbergen. Niko wanted to persuade us to return to Oxford, where he had obtained an attractive research grant to offer me, and where Marian could write up her doctoral research, which, as Niko could see, was going well at Berkeley. The Tinbergens returned to Oxford, leaving us to think about the offer. We decided to accept it, but meanwhile Niko had written of a new opportunity. Oxford had decided to appoint a new university lecturer52 in animal behaviour linked to a fellowship at New College, and Niko wanted me to apply. This teaching job would not preclude the research grant he had earlier promised me. I agreed to apply for the lectureship, and Oxford flew me over for the interview.

It was a magical trip, with what seemed like all before me. Music stamped the memory: Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, which I listened to on the plane, spellbound by the Rocky Mountains below and by exciting prospects ahead. Oxford put on its very best performance, which is the Maytime blossoming of cherry and laburnum all along the Banbury Road and Woodstock Road. New College, too, played its golden fourteenth-century part and I was happy, my exuberance not dimmed when I was greeted on arrival by the news that Colin Beer, former member of the Oxford ABRG and now a professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey, had put in an unexpected late application for the lectureship. Even the fact that Niko had excitedly switched his allegiance from me to Colin didn’t upset my optimistic mood. If Niko had decided that Colin was a better bet, that was good enough for me. I would still have the research position and, as I told the interviewing committee, if Colin were there in Oxford too, so much the better. They did indeed give the job to Colin, and I took up the research grant.