In this age of heightened spectacle and pervasive surveillance, kitsch is a relatively innocuous form of cultural persuasion and political manipulation, almost outmoded as such. Yet, after 9/11, it returned with a vengeance in the United States. Why?

The word kitsch is related to the German verkitschen, “to cheapen,” and an elitist concern about the debasement of cultural value pervades most accounts of the subject. Kitsch has attracted—that is to say, repelled—novelists from Hermann Broch to Milan Kundera and critics from Clement Greenberg to Saul Friedländer, all of whom were prompted to address the topic at times when mass culture and politics took an ominous turn—Broch and Greenberg after the rise of fascist regimes in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, and Kundera and Friedländer during the decay of totalitarian regimes in the 1970s and 1980s.1 According to all these writers, kitsch cuts across culture and politics and corrupts whatever integrity might remain to either sphere.

In 1933, as the Nazis came to power, Broch referred kitsch to the emergent bourgeoisie of the early nineteenth century. In his view, this class was caught between contradictory values, an ascetic commitment to work on the one hand and an exalted faith in feeling on the other. For Broch, the initial form of kitsch expressed an unlikely compromise between these two attitudes, a blend of prudery and prurience, with expressions of sentiments that were at once chastened, keyed up, and made saccharine. Broch was categorical about the disastrous effects of kitsch—he called it “the element of evil in the value system of art”—and Greenberg agreed.2 In another momentous year, 1939, Greenberg underscored the capitalist dimension of the phenomenon: “a product of the industrial revolution,” kitsch was an ersatz version of “genuine culture,” which the bourgeoisie, dominant by the mid-nineteenth century, sold to a peasantry-turned-proletariat, that is, to a class stripped of its own folk traditions once it was drawn into the cities to labor in the new factories. Soon industrially produced, kitsch became “the first universal culture ever beheld,” and as such it abetted “the illusion that the masses actually rule.”3 It was this illusion, Greenberg suggested, that made kitsch (with variations according to political ideology and national tradition) essential to the regimes of Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin.

Greenberg also underscored how kitsch dictates its own consumption through predigested forms and programmed effects. This notion of “fictional feelings,” which are general to many people but specific to none, led Theodor Adorno, in Aesthetic Theory (1970), to define kitsch as a parody of catharsis.4 It also allowed Kundera, in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984), to argue that its warm and fuzzy affect is instrumental to our “categorical agreement with being,” that is, to our assent to the proposition “that human existence is good” despite all that is “unacceptable” in it, the reality of shit and death above all, which it is “the true function of kitsch … to curtain off.” In this expanded definition, kitsch engineers a “dictatorship of the heart” through “basic images” of “the brotherhood of man,” a feeling of fellowship that, for Kundera, is little more than narcissism writ large:

Kitsch causes two tears to flow in quick succession. The first tear says: How nice to see children running on the grass! The second tear says: How nice to be moved, together with all mankind, by children running on the grass! It is the second tear that makes kitsch kitsch.

It is also what makes kitsch, in societies ruled by a single party, “totalitarian,” and “in the realm of totalitarian kitsch, all answers are given in advance and preclude any questions.”5

During the Reagan years, Kundera was a darling of neoconservatives, who were pleased with his account of Communist society as a “world of grinning idiots” on “the Grand March” to the gulag.6 However, after the collapse of the Soviet bloc, aspects of “totalitarian kitsch” returned in the United States, presided over by some of these same neoconservatives. The differences were obvious enough: American administrations have tended to limit “the brotherhood of man” to the nation (which under Donald Trump has taken on a white-supremacist character), and they have felt little need to naturalize this ideology. Yet the similarities were marked as well: even though not all questions were precluded, many answers were given in advance (there were weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, Saddam Hussein was connected to al-Qaeda, American soldiers would be greeted as liberators, and so on), and we were surrounded by “beautifying lies” as noted by Kundera—a “spread of democracy” that often bolstered its opposite, a “march of freedom” that often liberated people to death, a “war on terror” that was often terroristic, and a trumpeting of “moral values” that often came at the cost of civil rights.

What does all this have to do with humble kitsch? In part, the blackmail that produces “our categorical agreement” operates through its tokens. Recall how support for the war on terror was urged on by all the decals of the World Trade towers draped with stars and stripes, the little flags on both working-class antennas and political-elite lapels, and the shirts, caps, and statuettes dedicated to New York City firemen and police. More direct still were the yellow ribbon stickers that exhorted us to “support our troops.” Part of the force of this sign was its legibility, which depended on an American custom, said to be in practice since the Civil War, whereby women “tie a yellow ribbon” in fidelity to men gone to battle. Yet this origin is mythical, put in circulation only after World War II by the 1949 John Ford film She Wore a Yellow Ribbon starring John Wayne as a cavalry officer in the genocidal Indian wars in the West.7 This is not to mock the symbol (its shallowness belies its strength), or to bemoan its taste, but rather to suggest how it served, qua kitsch according to Kundera, to “curtain off” the reality of shit and death. For, in lieu of images of flag-draped coffins here, let alone of blown-apart bodies there, we were sold items like those bows of ribbon inveigling our support—which was less for any troops than for an administration whose adventures were hardly in their best interests. From this point of view, these little bows were subtle collars that bound us sentimentally to the imperial project.8

Another prime example of Bush kitsch, this one concerning moral values, involved the brandishing of the Ten Commandments at state courthouses. The main protagonist was the infamous Roy Moore, when he was Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court (he was dismissed from office for refusing to remove his granite Decalogue), but there were related cases elsewhere. This act defied the separation of church and state, yet that was precisely the point: to proclaim the Ten Commandments to be far more fundamental than any Enlightenment principle in the Constitution. Here again, the historical source of these monuments is not deep; they date only to 1956 when, in a publicity stunt for his second version of The Ten Commandments, Cecil B. DeMille paid for a few hundred tablets to be placed in public spaces across the country. (Charlton Heston, who launched his career as Moses in that film, only to end it as head of the National Rifle Association, was active in the promotion.) Nevertheless, the monuments were far from absurd, for they militated for a convergence of church and state that was in keeping not only with political ambitions of the Bush administration but also with practical effects of its massive deficit, which was a calculated way “to starve the beast” of government, to defund social programs partly in the interest of church offerings—“Godfare instead of welfare.” The tablets emblematized this vanguard of the Right; they also epitomized its literal relation to the law, for, even as a constitutional principle was defied, the biblical letter was honored. (In part, this literalism stems from the Baptist doctrine of the inerrancy of the Bible, which effectively obviates the need to read it, let alone to interpret it. We are urged to read the Constitution in this manner too.)

In the instances of both the yellow ribbons and the commandment monuments, an exhortative voice slips into the imperative: “Support Our Troops,” “Thou Shalt Not …” Again, the rhetoric seems innocuous, but precisely as such it habituates us to a political language whereby policy positions—against racial equality, reproductive choice, LGBTQ+ rights, and so on—are presented as preordained, commands from on high, all answers given in advance. At the heart of kitsch, according to Kundera, is the “idiotic tautology ‘Long live life!’”9 Bush kitsch had its own version of this tautology, even as it seemed to define life as, optimally, the time between conception and birth. The thinking here is evangelical: if the Creation is one with the Fall, then the fetus is more innocent than the child and so more worthy of protection. (This line guided the Bush position on stem-cell research too, among other issues.) Not much has changed in this regard since that time.

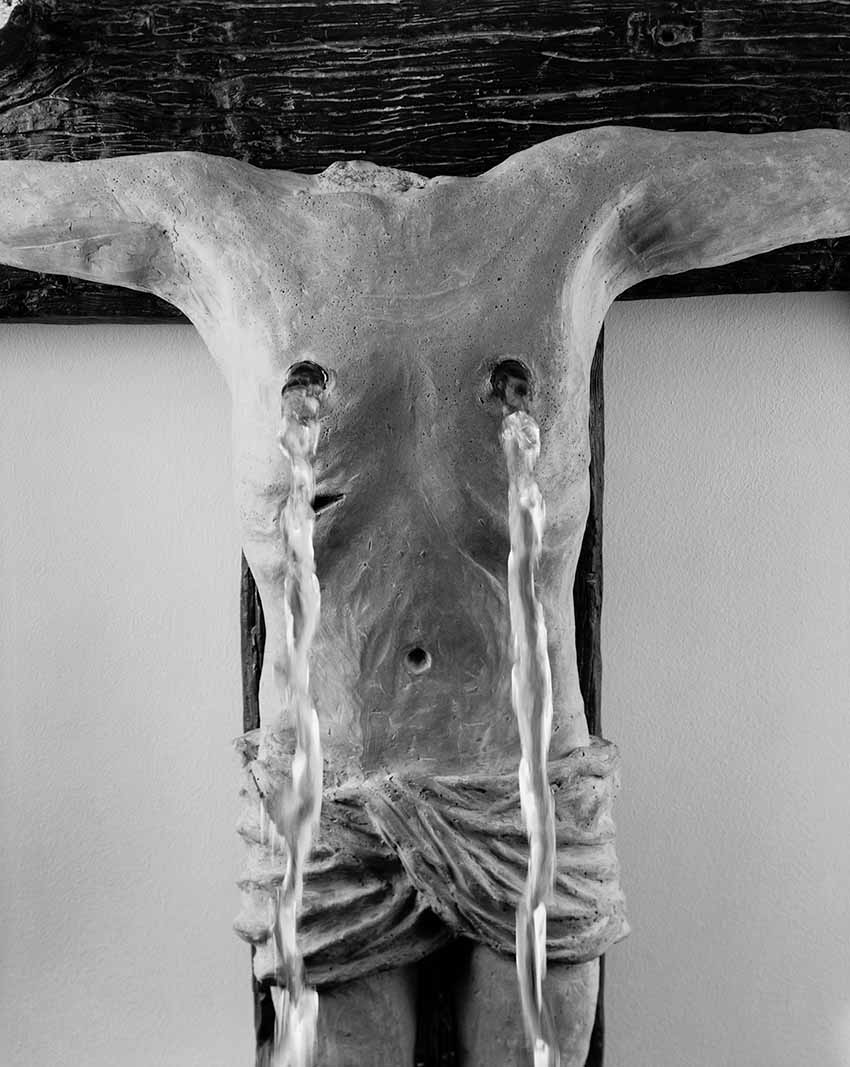

“The flag and the fetus [are] our Cross and our Divine Child,” Harold Bloom wrote under the first Bush; “together [they] symbolize the American Religion.”10 This complex was pressured further under the second Bush: if the fetus is sacrosanct, so is the flag soaked in the aura of the Cross. After 9/11 the Bush administration operated as if under the aegis of the wrathful Christ: we too have suffered, we too have a right to judge and to punish. In 2005 Robert Gober captured this complex with a crucified Christ made of cement. Decapitated (as though it were vandalized), his object is a mimetic exacerbation of Bush kitsch that draws equally on churchyard displays and 9/11 mementos.11 The acephalic Jesus is a crucial touch, for it condenses a mess of associations—reminders of beheaded hostages in Iraq as well as the hooded victim at Abu Ghraib, and, behind both images, the figure of America in the guise of Christ the righteous aggressor, the one who kills in order to redeem.