On November 21, 1963, the day before the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the historian Richard Hofstadter delivered a lecture titled “The Paranoid Style in American Politics” at Oxford University. Prompted by the presidential campaign of the Republican firebrand Barry Goldwater, Hofstadter argued that this distinctive mentality was animated by “conspiratorial fantasy”—the deep suspicion that there is always a diabolical cabal afoot in the country, whether it is the Freemasons, “the international gold ring,” “the Elders of Zion,” the Mormons, the Catholic Church, or (given that McCarthyism was not a distant memory then) Communist spies in the government. According to Hofstadter, this fear of political subterfuge stemmed from a feeling of sociopolitical dispossession, one that these “sufferers from history” overcome with a compensatory sense of spiritual empowerment: they alone see the truth.1 This is the tension that produces the apocalyptic tenor of paranoid politics, which boils down to the promise of redemption for them and the threat of damnation for everyone else. “The paranoid is a militant leader,” Hofstadter concluded, with “the will to fight things out to a finish.”2

Is there a complementary style in American representations of religious belief, a pictorial expression of dispossession transformed into empowerment, of dark conspiracy at war with revelatory light? One guide here is the artist Jim Shaw, who has collected a trove of promotional, pedagogical, and commercial materials—including homemade pamphlets, didactic banners, childish encyclopedias, and record albums—from evangelical movements, secret societies, and New Age spiritualists. (He has a good cache of Hollywood publicity for biblical movies as well.) Shaw calls this particular archive “The Hidden World,” a title borrowed from a conspiracy magazine of the 1940s. And what these groups have in common is indeed a self-certified claim on the secret reality that the rest of us, blinded by sin, ignorance, or denial, fail to see. The conviction that they are both blessed and maligned leads them to depict the world in stark contrasts of light (again, only they behold the truth) and dark (there is a nefarious plot to defeat them)—that is, to portray the world in paranoid terms.

Other attributes of a paranoid style can be gleaned from “The Hidden World.” First, the sentimental manner of mid-nineteenth-century Christian art, such as the painting of the German Nazarenes or the English Pre-Raphaelites, is often updated by means of illustration.3 Such images reprocess the Bible through the idioms of comic books, blockbuster movies, and album covers, in such a way that the aura of Christ might be recharged with the power of the sci-fi superhero or with the glamor of the matinee movie idol. Also pronounced in this representation is the particular character of “the American Jesus,” as Harold Bloom termed it in The American Religion (1992). “Solitary and personal,” this is the resurrected Christ, not the crucified one, and American salvation is thought to come through “a one-on-one act of confrontation” with this Jesus alone.4 Accordingly, the religious images in “The Hidden World” place a premium on scenes of transformation; in many instances, the act of representation becomes one with the event of revelation. This conflation makes the pictorial language always dramatic and sometimes violent; it bespeaks a “doomeager freedom,” Bloom writes, “from nature, time, history, community, other selves.”5 Usually, the perspective in these pictures is designed to be personal (the subject and the viewer are targeted for illumination) or projective (we are about to be carried away in rapture) or both at once. Occasionally, there is a strange oscillation between the first days and the last days, between Genesis and Apocalypse. (Bloom reminds us that the Gnostic version of creation as catastrophe runs deep in the American Religion.)

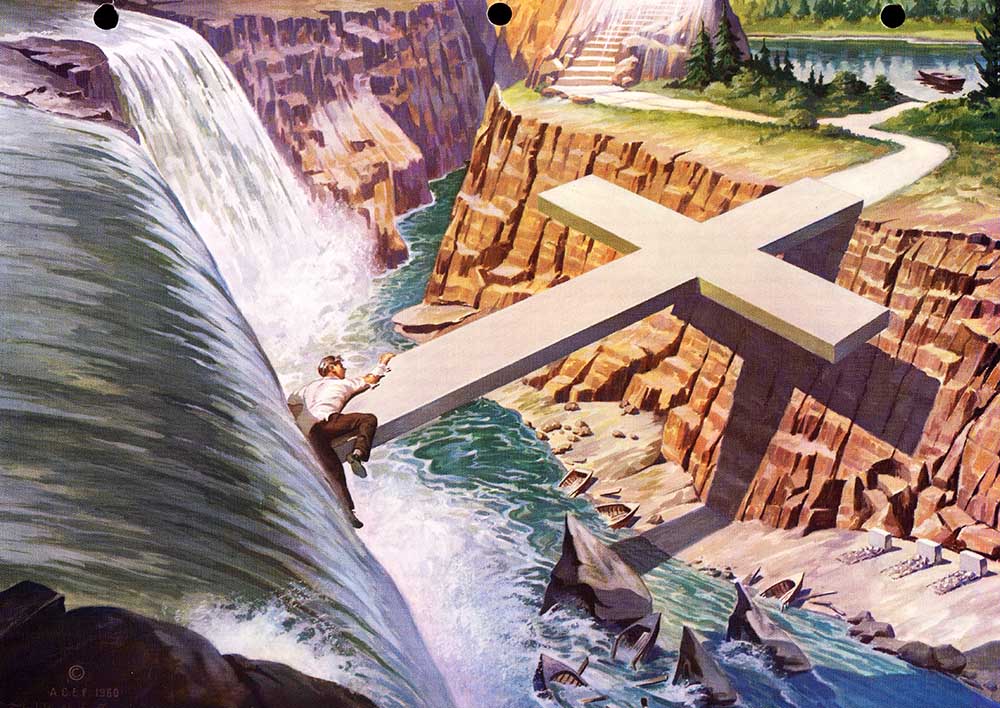

The poet Hart Crane once wrote of the American desire for “improved infancy,” and this wish is also expressed in some images in “The Hidden World.”6 One effect is that sexuality becomes almost impossible to represent: if Superman has a black void for his genitals, the American Jesus is even blanker down below. Yet, sometimes in this patriarchal universe, the phallus is only displaced, often onto the cross, which thereby becomes an agent of supernatural powers. In one illustration in “The Hidden Order” (produced by Walter Ohlson for the Bethel Lutheran Church in the mid-1960s) we see a man about to plunge down a great waterfall to his ruin, only to be saved by a giant white cross that suddenly appears to bridge the awful abyss and to offer a wondrous path to the idyll on the other side (which includes a stairway to heaven in the distance). The parting of the Red Sea in the Cecil B. DeMille extravaganza The Ten Commandments (1956) has nothing over this great escape, and in both instances divine miracles are rendered as special effects.

Walter Ohlson, Bridge Over Troubled Waters, c. 1960. 30 × 40˝. Poster from the Jim Shaw collection “The Hidden World.”

The paranoid dimension of these representations is clearest in the didactic materials collected by Shaw, such as diagrams that present biblical stories and historical events as either prophetic or conspiratorial or both. In such schemes, everything happens for a reason, which might serve as a quick definition of paranoid thought. Yet, often, this strident conviction stems from a great doubt that must be overcome. “The delusion-formation, which we take to be a pathological product,” Freud reminds us about paranoid fantasy, “is in reality an attempt at recovery, a process of reconstruction,” which usually fails spectacularly.7 Sometimes, this attempted reconstruction of a collapsed world is expressed, pictorially and textually, by an overelaboration of a private system that, because it is under such pressure to mask complications in history or differences in faith, tips into the opposite of order—a vision that is arbitrary and chaotic.

One banner in “The Hidden World” calls out “false prophets” (it names Emanuel Swedenborg and Joseph Smith, among others), which suggests that, if there is only one truth, each prophet must expose every other as a pretender in order to monopolize it. This relay between believing and debunking is made vivid by another archive assembled by a contemporary artist, in this case Tony Oursler. Gathered over the last few decades, his collection called “Imponderable” draws from more than 3,000 photographs, props, souvenirs, publications, and other documents, concerning mesmerism, hypnotism, magic, the occult, thought photography, automatic writing, spirits, and UFOs. “This is the true essence of debunking,” Peter Lamont (who is both a magician and a historian of magic) writes in the publication of these materials; “it is not the rejection of belief. It is the promotion of one belief over another.”8 Thus, famous exponents of empiricism, such as Arthur Conan Doyle, could also be gullible believers, and celebrated practitioners of illusion, such as Houdini, could also be assiduous debunkers. Among these skeptics was Fulton Oursler, grandfather of Tony and author of The Greatest Story Ever Told (1949), the book about the life of Jesus that was the basis of the 1965 movie of that title.9

“Imponderable” is the term that eighteenth-century scientists used to describe forces like magnetism that they could not quantify, but it also indicates the nebulous zone between fact and fabulation that Oursler explores. And, as we range over his collection, what emerges is not a clear opposition of truth and falsehood, science and spiritualism, or even honest demonstration and faked act, but a murky dialectic of rationalization and irrationalization whereby the former often supports rather than challenges the latter. For example, an advance in the medium of photography might aid a belief in mediums of other kinds, as when a manipulated photo seems to capture a blob of ectoplasm projected by a spiritualist in a trance.10

No more than Shaw does Oursler condescend to his material, and that suspension of disbelief is essential to the power of their collections, which both artists use to great effect in their own work as well. One reason why rational argument, not to mention critical demystification, is often ineffectual today is that the paranoiac believes in his constructions more fervidly than sane people trust in things as they are.11 If convinced enough, the paranoiac can convince others; in fact, as we see with Donald Trump, conviction is hardly required to work the trick of blatant obfuscation and outright lie. Etymologically, “bunk” derives from the vapid speech of an early nineteenth-century congressman from Buncombe County, North Carolina, and debunking—taking the piss out of political bullshit—remains a necessary activity.12 This is the place where “Imponderable” gives one pause, for again and again it traces a vicious circle connecting mystification and demystification, bunkers and debunkers. That circle has both expanded and tightened with the internet, which seems to proliferate repulsive ideologies far more often than it purges them.