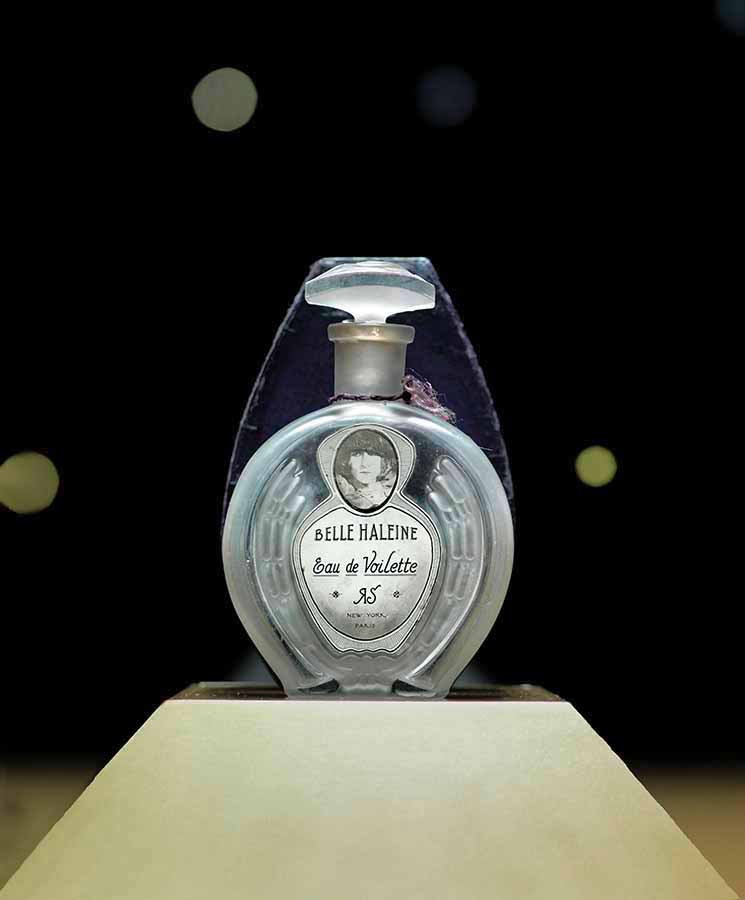

Belle Haleine (1921) is said to be the only “assisted readymade” actually produced by Marcel Duchamp that is still extant. For this piece, Duchamp appropriated a flacon of Rigaud perfume and substituted an elegant label that includes a Man Ray photo of his own alter ego, the mysterious Rrose Sélavy. Above the label appears the complete title, Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette, the brand name RS (with the R reversed), and a double place of origin, New York and Paris. In January 2011 Belle Haleine was displayed continuously for seventy-two hours at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. Signed by Rrose Sélavy and dated 1921 on the back, the Rigaud box framed the bottle, and the presentation was theatrical in the extreme: like a crown jewel, the spot-lit Belle Haleine was set in a glass case on a coppery plinth and placed alone in the center of the vast Mies van der Rohe pavilion.

Although celebrated as the artist who opened high art to the common thing, Duchamp also rarefied the everyday object, including the replicas of his readymades that were fabricated in the 1960s. His refashioned flacon seems to anticipate this destiny, and, in many ways, Belle Haleine is the sublimated counter to his famous urinal—with associations of perfume rather than piss, femininity rather than masculinity, refinement rather than vulgarity, enigma rather than obviousness. It also comes with exquisite puns: whereas Rigaud called its product un air embaumé (which can mean both “perfumed” and “embalmed”), Duchamp named his piece belle haleine (beautiful breath), and instead of the expected eau de toilette or eau de violette, he labeled his water eau de voilette (veil). Here Duchamp suggests that, for all the egalitarian pretense of the readymades, art will remain, in a capitalist economy that requires such categories, a magical elixir—the breath of genius, the aura of the artist, or (as Barbara Kruger has phrased it) the perfume of the gods. He also implies that art can only play its role if it is somehow veiled. Not incidentally, this is what Jacques Lacan said of the phallus: if it is exposed, it is just a penis.1 Ditto art: if it is exposed, it is just a thing.

Marcel Duchamp, Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette, 1921, as displayed at the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, January 27–30, 2011. 6½˝ high. Photo bpk Bildagentur / Art Resource, New York.

And what was the presentation of Belle Haleine at the Neue Nationalgalerie if not an unveiling? Inadvertently or not, everything was revealed—art as luxury product, museum as theatrical display, and all the rest. In fact, the exposé was pushed as far as it could go: a special showing of the precious survivor of the readymade family (fittingly, it was part of the Yves Saint-Laurent and Pierre Bergé estate), en route from a 2009 auction to its next destination (about which the museum remained quiet). Belle Haleine sold, well above its estimate, for 7.9 million Euros, so it was not only a deluxe item but also a sumptuary object that we came to behold. Can one smell the beautiful breath of 10 million dollars? What might the aura of excessive value look like? For three days and nights, Rrose peered out from under glass like a modern Mona Lisa (whom Duchamp had goateed just two years before) or an updated Helen of Troy, a beautiful haleine that launched a thousand Yves Kleins.

Again, the exposé was blatant, but our dilemma—which is not new but evermore troublesome—is that it hardly matters. The emperor (call it art, the museum, Duchamp, art as investment) has no clothes, and still its bare body, lit up by all those Eurodollars, ravishes. What we possess today is not critical knowledge so much as cynical knowingness about these matters, and most everyone is in on the joke.2 When I shuffled down the steps of the museum that winter night, I did so with a shrug: not only the device of the readymade but the enterprise of institution critique seemed kaput. Although a Berlin newspaper referred to the Duchamp as “the Trojan flacon,” it was hardly a Trojan horse. Belle Haleine, a museum brochure told us, was “displayed in a glass case of the same shape and size as the one Nefertiti occupies on the Museum Island. The time has now come for that case to hold an icon of the modern age.” Un air embaumé is right; another eroticized mummy bites the dust.

Yet this attitude might be cynical knowingness of my own, and, in any case, the readymade has had as many lives as painting has had deaths. The readymade is not only a tautology about art as speculative commodity; it is also a “creative act” (as Duchamp called it late in his career) that exceeds the intentions of any artist or curator, a performance of presentation that can still draw out latent contexts.3 In Berlin, the context that came into view involved relics as much as icons. Rrose Sélavy is Duchamp cross-dressing as feminine, to be sure, yet she is also Duchamp passing as Jewish (homonymically as Rose Halévy). In this setting the appellation took on a new significance, with the Neue Nationalgalerie not far from the “Topography of Terror,” the site of SS and Gestapo headquarters (where there is an extensive display of their genocidal operations), and with the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe to the northeast and the Jewish Museum to the southeast. A flacon like the one refashioned by Rrose could appear in a photograph of possessions appropriated in the mass deportation of Jews to the extermination camps.

Berlin is a place where such associations are provoked every day. Belle Haleine behind glass called up another unearthing of long-lost objets trouvés on view at the Neues Museum (where Nefertiti reigns) in November 2010. In January of that year, as workers dug a new U-Bahn station near city hall, they uncovered a bronze figure, not ancient but modern, a bust of a woman by an obscure artist named Edwin Scharff. More discoveries followed in August—Dancer by Marg Moll, Standing Girl by Otto Baum, and fragments of heads by Otto Freundlich and Emy Roeder—and still more emerged in October, eleven in all. It turns out that these modernist sculptures were survivors from the Nazi collection of art designated “degenerate.” Some were exhibited at the infamous exhibition of that name of 1937–38 and then returned to the Propaganda Ministry, where they were presumed to be destroyed or sold abroad for hard currency—that is, until their recent rediscovery. Evidently, a tax lawyer named Erhard Oewerdieck, who had a nearby office in 50 Königstrasse, had gathered up the works, perhaps to preserve them.4 When Allied bombs hit the building in 1944, it collapsed, covering the sculptures and everything else. (If there were any works on canvas or in wood, they were incinerated.) Despite its softer fate, the perfume bottle by Rrose Sélavy would have qualified as “degenerate” too.