Born in 1944 to an Indian father and a German mother, Harun Farocki studied at the German Film and Television Academy in Berlin from 1966 to 1968. This places him in the ambit of the celebrated directors of New German Cinema, such as Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Werner Herzog, and Wim Wenders, but his practice is closer to the engaged filmmaking of Alexander Kluge, Helke Sander, Jean-Marie Straub, and Danièle Huillet. Politicized by the Vietnam War in the 1960s and the Red Army Faction in the 1970s, Farocki, like these near contemporaries, developed a critical cinema, focusing on the image as “a means of technical control.”1 This criticality is key to his work, which is also marked by its range: well over 100 films and videos, many made for television; numerous radio pieces; a long list of books, articles, reviews, and interviews; and, relatively late in his career, a good number of image installations in galleries and museums.2 The films vary, both in style and in topic, from a psychological thriller to the essay films for which Farocki is most celebrated. He left numerous projects unfinished upon his death in 2014.3

Among the essay films are Images of the World and the Inscription of War (1988), How to Live in the German Federal Republic (1990), Videograms of a Revolution (1992), Workers Leaving the Factory (1995), I Thought I was Seeing Convicts (2000), and Eye/Machine I–III (2001–03). Here, Farocki recovers, recuts, and reframes archival images—largely drawn from institutional records, industrial films, instruction videos, surveillance tapes, and home movies—of various subjects such as labor practices, training methods, weapons tests, control spaces, and everyday life. Often, he slows these images down, repeats them in different juxtapositions, and discusses them in voiceovers that range from the analytical to the deadpan; the effect is that we seem to see these representations, with Farocki, for the first time. In this respect, his essay films are pedagogical but not pedantic: the intelligence in play, extracted from the images and inflected by the commentary, is too quizzical, elliptical, and generous to be felt as reductive or rigid, and the filmic voice cannot be identified strictly with Farocki in any case.4 His reworking of montage as a recurrent clustering of adjacent leitmotifs also leaves much for viewers to do; we are invited to mull over the image-texts that Farocki assembles for us. (“I try not to add ideas to the film,” he remarked; “I try to think in film so that the ideas come out of filmic articulation.”)5 In fact, we are invited to think these combinations dialectically as best we can, with the tacit understanding (if we attend to the ethics of the filmic voice) that the puzzle will remain open in the end—a problem to reconsider, precisely an essay to revise, at a later moment, in a different conjuncture.

The essay films have both a forensic dimension and a mnemonic imperative. From Images of the World to Eye/Machine and beyond, Farocki juxtaposes emblematic images from various moments in capitalist industry—a simple punchpress, say, with a sophisticated missile—in order to retrieve the relation, both technical and lived, between different kinds of labor, war, and representation. Again and again, he returns to instruments of seeing and imaging in order to stage a dialectic of new media and outmoded forms, foregrounding the role of cinema as he does so. This concern not only focuses his practice but also grounds it in its means. This allows Farocki to show as much as to tell, and what he shows above all are signal transformations in vision and representation. Often, he presents his assorted devices—perspective engravings, aerial photographs, military films, televised spectacles, video games, and computer models—not merely as effects of technological transformation but as indices of its most significant shifts. Like Marx, Farocki implies that each new phase of production and reproduction sets up a new relay of power and knowledge, and, like Michel Foucault and Jonathan Crary, he suggests that each new relay involves a new modeling of the subject.6

Although Farocki sometimes reflects on Renaissance perspective, more often he dwells on the birth of film. “Central to his work,” writes media historian Thomas Elsaesser, “is the insight that, with the advent of the cinema, the world has become visible in a radically new way, with far-reaching consequences for all spheres of life, from the world of work and production, to politics and our conception of democracy and community, for warfare and strategic planning, for abstract thinking and philosophy, as well as for interpersonal relations and emotional bonds, for subjectivity and intersubjectivity.”7 Some of these consequences were already explored in Pop art—one thinks immediately of Andy Warhol—yet Farocki does not redouble the image world as passively as Warhol does; again, he works to indicate its historical trajectory through a partial archaeology of its telltale devices. Moreover, Farocki was driven by a Brechtian imperative to repurpose these “inscriptions,” and in this respect he acknowledges Brecht along with Warhol as his “most important influence.” “In both cases,” Farocki argued, “the impulse is to avoid naturalizing the image. The difference is, of course, that Brecht wants to develop a mode of representation, while Pop art annexes one.”8 In effect, Farocki applies Warholian means to Brechtian ends: he too annexes found images—that is, both cancels and subsumes them—in order to insist on a critical relation to seeing and imaging alike.

“My way,” Farocki commented, “is to look for submerged meaning, clearing away the detritus on the images.”9 This desire to lay bare is also quintessentially modernist; at the same time it draws on the ideology critique so central to the Marxist tradition, especially as developed first by Brecht and then by Roland Barthes in Mythologies (1957).10 Farocki reviewed that seminal text soon after its German publication in 1964, and his essay films do serve as myth critiques à la Barthes, that is, as analytical rearticulations of ideological images. The association of Brecht and Warhol also conjures up Jean-Luc Godard, another important influence on Farocki. Like Godard, Farocki produced a political meta-cinema. Yet, whereas Godard focused on the classic Hollywood genres of film, Farocki concentrated on its military-industrial exploitation; and whereas Godard assumed a realist match between camera and eye that he moved to disrupt, Farocki demonstrated a perpetual retooling of eye by camera that he worked to deconstruct.11 This refashioning, proposed in Images of the World and elaborated in Eye/Machine, is the central concern of his practice.

The title of Images of the World and the Inscription of War underscores both that the world is mediated by images and that war is fundamental to that mediation; “inscription” further implies that these conditions require decoding. Immediately, then, Farocki announces his primary theme—the imbrication of instruments of representation with those of destruction—which the 75 minute film examines through specific instances. As they are repeated, these examples take on the hermeneutic form of allegorical objects—technical objects that we decipher in their own right and then use to decipher other such objects. We begin and end with a wave machine in a marine laboratory in Hanover, Germany, which figures the control-through-reproduction of nature. In its repetitive movement the device appears as inexorable as the sea and so comes to signify less technological ingenuity than mechanistic indifference, a world without qualities, indeed almost without humans. Next, in a dialectical move, Farocki relates this insistent extension of human attributes into the natural world to the historical development of individual perspective both in the Renaissance (he shows us engravings by Dürer on the subject) and in the Age of Reason (here he reflects on Aufklärung, the German term for Enlightenment). The connection between perspective and individualism recalls the Heidegger of “The Age of the World Picture” (1938), while the allusion to the history of rationality echoes the Adorno and Horkheimer of Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), yet Farocki revises these different critiques with his own distinctive account of the ideological dimension of representation.

Farocki does so, first obliquely, through an anecdote about one Albrecht Meydenbauer, who in 1858 set out to measure the facade of the cathedral in Wetzlar, Germany, for the purposes of its conservation. After he nearly fell to his death, Meydenbauer devised a method for the scale measurement of buildings by means of photographs. This cluster of image-ideas is typical of Farocki: a mortal danger prompts a technical innovation, a desire for control through representation, but, in this mingling of desire and technique, scientific reason slips into instrumental use. Meydenbauer went on to propose an institute for scale measurement (which was essentially an archive of architectural images) that the Prussian War Ministry supported for its own military purposes. Too often, Farocki implies, representation and conservation are not far from war and destruction.

Later in his genealogy of visual instrumentality Farocki reflects on the slippage, in the word Aufklärung, between “enlightenment” and “reconnaissance” (in the sense of intelligence gathering). He retells the story of an American war plane that, on a bombing run to Silesia on April 4, 1944, inadvertently photographed Auschwitz, only to have this evidence of the death camp go undetected by military analysts focused on the I.G. Farben complex nearby. In 1977, inspired by the television series Holocaust, two CIA employees searched the old military files with the new technical aid of a computer, found the relevant images, and performed the analysis of the camp that their predecessors had failed to produce thirty-three years earlier. In this sequence, Farocki juxtaposes a great capability to “reconnoiter” with a fatal inability to “recognize” in order to demonstrate how tragic the split between imaging and understanding can be.12 He then associates this failure to see with a further failure to listen (Farocki insists that visual evidence requires testimony as well as analysis) through the story of two prisoners, Slovakian Jews named Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, who, against all odds, escaped Auschwitz, only to have their report of its horrors ignored first in Switzerland and then in London and Washington. Finally, Farocki suggests that this split between reconnaissance and recognition is still inscribed in contemporary technologies of seeing and imaging such as satellite surveillance.

Harun Farocki, Images of the World and the Inscription of War, 1988. 16mm film, color and black-and-white, 75 minutes. © Harun Farocki GbR.

Our representational devices inform not only how we see but also how we appear, and Images of the World pressures this tension between imaging and being imaged. In the Auschwitz sequence, Farocki lingers over an extraordinary photograph of a new arrival to the camp, an attractive woman in an overcoat, who darts a furtive glance at the camera, while behind her a Nazi soldier inspects several male inmates. Even now, the implication of gazes here is difficult to bear, but at least the woman retains enough self-possession to look back at her Nazi photographer with what appears to be a mix of fear and outrage. Elsewhere in the film, Farocki presents another stark encounter between camera and subject: archival portraits of Algerian women photographed in 1960, for the first time without veils, by the French military for purposes of identification during the war. These women are exposed in every sense of the word, but the violation is also literally faced and mutely resisted.13 Toward the end of Images of the World, when Farocki shows us a life-drawing class in session, the cumulative effect of his montage is such that we can no longer hold humanist uses of seeing, measuring, and imaging apart from military, industrial, and bureaucratic abuses of such techniques. While some of us are positioned as objects of this general image-science, Farocki concludes, others are set up as its operators. Then, too, we might occupy both positions; our training is as innocuous as playing a computer game or watching a war report on television.

Farocki pursues this concern with training in How To Live in the German Federal Republic, which draws heavily on instructional tapes—a young boy quizzed with a block puzzle, pregnant parents coached with baby dolls, schoolchildren drilled about street traffic, bank tellers and police cadets trained in dispute management—in order to suggest how lessons in proper behavior shade into forced socialization.14 (In this footage, not only are people tested, but so too are things, such as drawers, chairs, and toilet seats, subjected to robotic abuse; it appears that the ideal of all these test subjects, human and other, is to be an object that can withstand a beating.) In an administered society, Farocki suggests, how to live has all but subsumed living as such, and in this respect the film looks ahead to our present regime of relentless testing and continuous retooling.15 Moreover, as a documentary of dramatizations, How to Live also anticipates our post-Warholian age of reality television, in which real life often feels real only if it is performed and living sometimes seems synonymous with acting out. While Farocki develops related lines of inquiry in his later films on prisons and shopping malls, Eye/Machine III links them directly with the themes first broached in Images of the World.

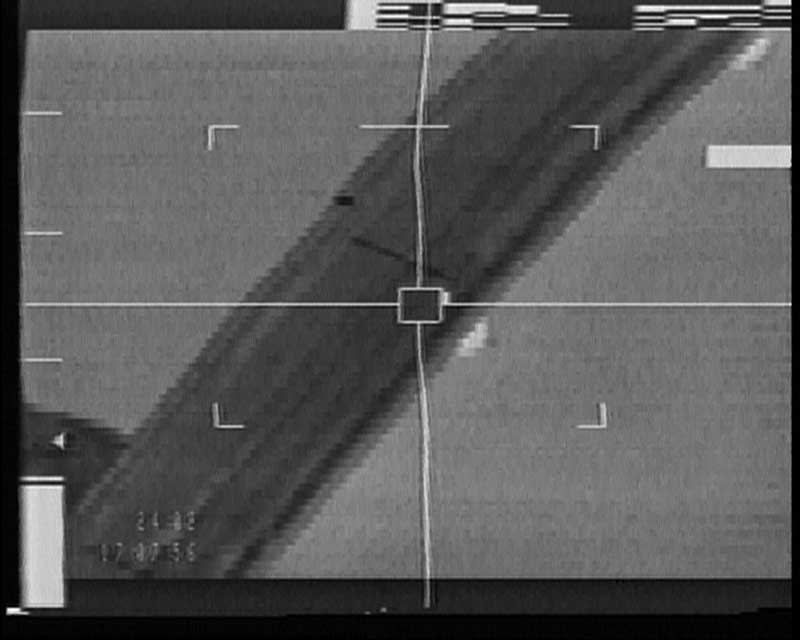

Like Images of the World, the Eye/Machine trilogy reflects on instruments of work, war, and control, especially ones advanced since the first Gulf War of 1990–91—new techniques in robotic production, missile weaponry, and video surveillance. (Images recur in the three parts, which are 25, 15, and 15 minutes long, respectively.) Here, too, the title of Eye/Machine immediately poses the question of relation. The slash evokes the old division between body and mind, and Farocki implies that the eye/machine problem is to our age what the mind/body problem was to thought after Descartes, with ramifications that once again outstrip the realm of philosophy. Does the slash signify a split between eye and machine (as often in Images of the World) or a new elision of the two, or a split that has produced an elision?

Farocki often divides his screen into two equal frames, sometimes set on a diagonal from upper left to lower right, with an overlap at the center (the film can also be shown on separate monitors). The effects of this split screen are multiple. It makes us aware of both imaging and framing as such, and so effects a distance that obstructs our customary identification with the camera. (His commentary interferes in a complementary way.) At the same time, the device mimics a targeting that, as in the smart-bomb images that repeat here, all but compels us to assume the camera view. However, the frames never quite converge: seeing-as-targeting is evoked, only to be suspended.16 Finally, the device calls up a history of image instruments from the stereoscopes of the mid-nineteenth century to the split screens of the present. Emphatically, neither a window nor a mirror (the traditional models of realist representation), this screen represents a dominant paradigm of visuality today—a monitor of information that we manipulate but that can monitor us in turn. As presented by Farocki, this surveillant gaze seems almost beyond the human. As with Images of the World, a principal concern of Eye/Machine is the gradual automation not only of labor and war but also of seeing and imaging. Farocki is fascinated by the affectless, even subjectless, operations of information processing and data matching. Often in the world of Eye/Machine no one seems to be home or at work.17

The first allegorical object in Eye/Machine I is the smartbomb targeting made infamous during the first Gulf War. What kind of subject position is projected by this particular eye machine? It is one of great power, for it sees what it destroys and destroys what it sees. The targets on the ground appear tiny, and, since the cameras explode with the bombs while we do not, we feel empowered by the destruction that we seem to direct: in a technological updating of the sublime, objective devastation is converted into subjective rush.18 Farocki also presents less extreme instances of eye machines, such as surveillance footage of workplaces and (sub)urban areas—traffic in a street, people in a mall—yet once again image and space have merged into one zone of continuous control. The viewer posited by the surveillant machine scans and prevents: if, as Walter Benjamin suggested, Atget photographed Paris as though it were a crime scene, surveillance cameras target citizens as proto-criminals.19 More examples of eye machines follow—a missile in flight, a sophisticated robot, satellite images of the Dubai airport from Gulf War I, and so on. “These images are devoid of social intent,” Farocki comments; they are not authored, and, as they mostly survey the predetermined, they appear to be more automatically monitored than humanly viewed. In this way Farocki intimates that a “robo eye” is in place, one that, unlike the “kino eye” celebrated by the modernist filmmaker Dziga Vertov, does not extend the human prosthetically so much it replaces the human robotically. Rather than an optical unconscious, Eye/Machine points to a postsubjective seeing, a visual nonconscious.20

Harun Farocki, Eye/Machine I, 2001. Two videos, color, 23 minutes. © Harun Farocki GbR.

At one point, Farocki plays on the term erkennen, which means “to recognize” as well as “to perceive.” With eye machines, recognition is further emptied of humanist content; it signifies little more than the faculty of a smart drone, the algorithmic capacity to compare live images with stored data, to process information, and to select action accordingly. Ironically, the smart drone is the chief protagonist of Eye/Machine; here whatever remains of autonomy, the ideal of the Enlightenment, seems to be on the side of automated missiles, robots, surveillance cameras, and other eye machines. This has dire consequences for labor, a focal interest for Farocki. As Elsaesser suggests, ever since the Lumière brothers made their first film, Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory in Lyon (1895)—that is, ever since cinema and industry “made contact, collided, and combined”—“more and more workers have been leaving the factory.”21 Again and again Farocki returns to this workplace (he made his own Workers Leaving the Factory in 1995, the centennial of the Lumière version); yet when he does so in Eye/Machine, he finds it so automated as to be almost absent of humans. However, like the body, work is never transcended; it is only relocated and redefined, and in Eye/Machine III there is no end of such training. Farocki shows it underway at video arcades, in front of computer games, through army advertisements, and so on. All viewers of the Gulf War series, he implies, were also “turned into war technicians.” This is another of his central themes that elaborates on Benjamin: in a fascist manner such images have produced a pervasive empathy for the technology of war.

Perhaps the grimmest implication of Eye/Machine is left unspoken, if not unseen. Images of the World examines a reality that could still be captured by the indexical inscriptions of photography and film; however mythical or mute the images might be, traces of facts could still be extracted from them, laid bare in a hermeneutics of suspicion. Eye/Machine points to a digital reformatting of that old analogue world in which images stream as phosphorescent information and screens can be reset without residue, a universe of image flow that might shape reality one moment and dissolve it the next. This world in which everything appears mutable and nothing transformable is hardly new (it is one definition of capitalist modernity as proposed in The Communist Manifesto [1848]: “all that is solid melts into air”), but the technology available to our current masters in this respect is awesome.

Here, Farocki faces a difficulty. Eye/Machine surveys a world of intensive alienation, not merely of man from world but also of world from man; it shows an environment of our own making that has moved beyond our reach. If this is so, can a Brechtian alienation-effect contend with it? That is, if extreme alienation is a general state, its mimetic exacerbation—the great old dare of Marx to make reified conditions dance to their own tune—offers little in the way of real challenge: it might fall on deaf ears and dead feet.22 Again and again, Farocki shows consciousness drained from images of the world, but, if this is the case, then his own manipulations might be pointless. After a viewing of Images of the World and Eye/Machine, any grid—a perspectival painting, a computer screen, a living room window—begins to look like another target, a cross-hairs about to line up.

At one point in Images of the World, Farocki quotes Hannah Arendt to the effect that concentration camps were laboratories of totalitarianism that proved “absolutely everything is possible” when it comes to the human domination of other humans.23 In Eye/Machine, Farocki updates this proof. This remains essential work, even though it tends to force him beyond critical dialectics toward stark oppositionality. Yet such opposition ran deep in this old 1968er, and this adamant will to resist unbridled power is what the Left needs most of all. At the end of a 1982 essay on the Vietnam War, Farocki quotes Carl Schmitt on the figure of “the partisan.” If the “immanent rationalization of the technically organized world is implemented completely,” Schmitt wrote in 1963, “then the partisan will perhaps not even be a troublemaker. Then he will vanish of his own accord in the frictionless performance of technical-functional processes, no different than the disappearance of a dog from the freeway.”24 However frictionless the freeways of our time might appear, the partisan work of Harun Farocki must not be allowed to vanish.