Over a century ago, new technologies transformed the aesthetic field, as painting and sculpture were pressured by photography and film, and modernists like Walter Benjamin and László Moholy-Nagy redefined literacy as the ability to read both. As is well known, Benjamin thought that the reproducibility of these media might not only shatter the auratic power of the unique artwork (this was mostly wishful thinking on his part) but also, in doing so, open artistic practice to other purposes, especially political ones (this came to pass, for good and for bad). Additionally, Benjamin underscored that the camera revealed the existence of things beyond the limits of human vision, which he termed “the optical unconscious.”1 However, if photography and film captured the real in impressive ways, gradually, as they were woven into the fabric of everyday life through magazines, advertisements, and the like, they served to derealize the world too, and by the 1960s terms like spectacle and simulation were needed to grapple with the effects. Back then, mechanical reproduction and mass circulation altered representation and subjectivity; now digital replication and internet distribution do the reformatting, and once again the changes are difficult to grasp. Today, many images neither document the world nor derealize it; rather, the viral ones model their own realities, often without our agency and against our interests, and this is also true of information when its flows suddenly stop and spasmodically erupt as purchase prompts or news flashes.

In the bulletins collected in Duty Free Art (2017), the German media artist and theorist Hito Steyerl describes this condition, which might be termed “the algorithmic nonconscious,” as follows:

Contemporary perception is machinic to a large degree. The spectrum of human vision only covers a tiny part of it. Electric charges, radio waves, light pulses encoded by machines for machines, are zipping by at slightly subliminal speed. Vision loses importance and is replaced by filtering, decrypting, and pattern recognition.2

Forget about literacy in photography and film; today, competence is about detecting how “reality itself is post-produced and scripted,” and about navigating “the networked space” of “the military-industrial-entertainment complex,” with its “junk images,” “serious games,” and “postcinematic affects.”3 Steyerl offers these final four terms as part of a survival lexicon for contemporary life caught in the capitalist web.4 In her view, this life threatens to become an endless match of Captcha (as in “Completely Automated Public Turing Test to tell Computers and Humans Apart”): as we meekly type in squiggled texts as prompted by websites, Steyerl notes drily, we “successfully impersonate a human for a machine.”5

How to attain the requisite literacy today, how to cope with the Captcha regime? According to Steyerl, we must meet it on its own amorphous ground and learn to see and to think as its programs do—scanning, decoding, and connecting—even if they beat us badly at this game. Thus she calls for crash courses in apophenia, or the perception of significant patterns in data, as well as in inceptionism, or the extraction of salient information from internet noise though “deep dreaming” (her neologism riffs on the 2010 Christopher Nolan movie Inception about a corporate dream-thief).6 Further, Steyerl urges us to marshal these skills in a new mode of interventionist interpretation, but it is not clear at what level it is to be pitched: “pattern recognition” suggests that it should occur on the noisy surface of data, whereas “inceptionism” implies that one must run as silent and deep as the dark web is said to do. While the first level conforms with the poststructuralist emphasis on the chatty superficiality of signs, the second points to a refurbishing of an old hermeneutics of suspicion that probes deceptive appearance for the true reality underneath. Yet how do we peel back our monitors, as Steyerl does literally in her 2010 video titled Strike, in which she takes a chisel to a lush LCD screen? Is this a call to exit the omni-workplace of the laptop, or a gesture that underscores the present futility of such strikes? Toto had only to pull back the curtain to expose the blowhard Wizard of Oz—how do we open up the black box of the fearsome military-industrial-entertainment complex?

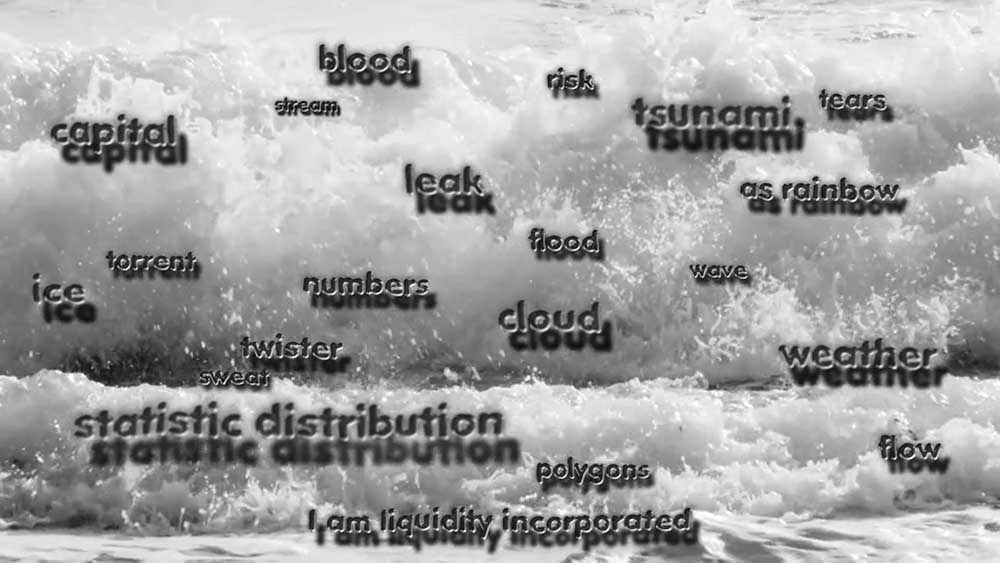

In her artworks and installations, Steyerl does what she can to unpack this dimensionless space of digital images, data, and assets and to reverse-engineer some of its typical forms. She draws on industrial films, instructional videos, computer games, and market reports in order to construct her mockumentaries in which she often appears, as pretend-guide or faux-stooge or both, to posit multiple connections between the expropriation of resources, the transfer of wealth, the militarization of technology, the retooling of labor, and the surveillance of everyday life. Her Liquidity Inc. (2014) is a characteristic bricolage of immersive images of mixed martial arts, weather systems, and high-speed trading that underscores the impossible demand on the capitalist subject today not merely to keep her head above the datascape but somehow to surf its flow.

For Steyerl, as for kindred practitioners like Trevor Paglen and Eyal Weizman, the key precursor is the late filmmaker Harun Farocki, for whom the computer had come to displace photography, cinema, and television as the dominant paradigm of contemporary visuality.7 No longer a screen of optical inscription and projection, this model is a surface of information that insists on a tight relay between eye, mind, body, and machine, and Farocki tracked our perpetual retooling as observer-operators in such innocuous activities as playing computer games or watching television. Like Farocki, Steyerl points to the gradual automation not only of labor and war but also of seeing and imaging, and she too is fascinated by the subjectless operations of information processing. Along with Paglen and Weizman, she bears down on the increased control by corporations and governments, through satellite imaging and information mining, of what is given to us as real in the first place—what can be represented, known, disputed—at all scales, from the individual pixel to the vast agglomerations of big data. In different ways, all these practitioners point to the urgent necessity of a science of agnotology, or the analysis of how it is we do not know or, better, how we are prevented from knowing.8

Hito Steyerl, Liquidity Inc., 2014. Single-channel HD video file. Courtesy the artist, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York, and Esther Schipper, Berlin.

So, again, how are we to peel back the screen and open up the box, how are we to stay on the surface of data and probe its depths—or is this old surface-depth opposition overridden by a digital order that appears both ontologically flat and epistemologically opaque? From Marx through Foucault, the watchword of critique on the Left was to look for an effective purchase in the very form of power that was to be challenged. For the most part, Steyerl is not interested in this version of resistance. Her motto is “I don’t want to solve this contradiction, I want to intensify it,” and her modus operandi is less to demystify ideological beliefs than to exacerbate corporate protocols, ideally to the point of an explosive transformation.9 One example of this strategy is her influential text “In Defense of the Poor Image,” which was included in her previous collection The Wretched of the Screen (2012). A poor image is “a rag or a rip, an AVI or a JPEG” that is heavily compressed for digital circulation and so badly dilapidated in form. On the one hand, the poor image is “perfectly adapted to the semioticization of capital” in information; on the other, it is “a lumpen proletarian in the class society of appearances” that registers its own unhappy “appropriation and displacement.”10 On the one hand, it “transforms quality into accessibility”; on the other, it stands “against the fetish value of high resolution.” According to Steyerl, “the wretched of the screen” might point to “an alternative economy” that “builds alliances as it travels”; it might allow for “a platform for a fragile new common interest.”11

In The Wretched of the Screen, Steyerl offers another instance of extreme dialectics, a double take on the contemporary art world, which she sees as both “a cultural refinery for the set of post-democratic oligarchies” and “a site of commonality, movement, energy, and desire.”12 Within this cultural refinery, she notes in Duty Free Art, are storage sites for super-expensive works that lie hidden, like secret vaults in James Bond films, in Geneva, Singapore, and other semi-extraterritorial zones. Steyerl lambasts this system of “duty-free art” that might never see the light of day not only as a tax scam but also as a negation of the fundamental imperative of any artwork to be seen. At the same time, she detects in this “duty-free” status a new possibility for a reclaimed autonomy for art, one free of the duties of representation, exhibition, and promotion.

Steyerl goes all in on one position in particular: “One should not seek to escape alienation, but on the contrary embrace it as well as the status of objectivity and objecthood that goes along with it.”13 This is not a new wager in critical theory—in “The Mass Ornament” (1927) Siegfried Kracauer urged his contemporaries to pass through “the murky reason” of capitalist reification to its other side, and in Aesthetic Theory (1970) Theodor Adorno stressed that “a mimesis of the hardened” was central to the critical vocation of modernist art—but Steyerl takes it to an extreme.14 In her view, proletarian and postcolonial claims to be the true subjects of history are out of date, and recent feminist and queer demands for subjective recognition are misplaced too. “Subjectivity is no longer a privileged site for emancipation,” Steyerl writes in The Wretched of the Screen. “How about siding with the object for a change? Why not affirm it? Why not be a thing?”15

Perhaps under the influence of “the new materialisms” that have swept the art world in recent years, Steyerl amps up this empathy for the object in Duty Free Art.16 To justify this move, she points to a qualitative shift in our relation to networked image-products; in “corporate animism” today, she argues, “commodities are not only fetishes but morph into franchised chimeras.”17 Her thinking here is that we have projected our vital force into these magical entities so thoroughly that there is now more life in them than in us, and so we must reclaim what animation we can through identification with them. “To participate in the image as thing means to participate in its potential agency”: that says it all.18 Yet this empathy for the object is not a high-end affair for Steyerl, as her defense of the poor image attests. She pushes this identification further in Duty Free Art, which includes a call “to spark an improbable element of commonality” through “a cheerful incarnation of databased wreckage”—in a phase, “to become spam.”19

Just as there are poor images, there is impoverished writing, and Steyerl rises to the defense of this wretched language too, whose alienated quality she finds instructive. First, Steyerl considers the specific example of “International Art English” (IAE), the lingo of gallery press releases “full of grandiose and empty jargon often carelessly ripped from mistranslations of continental philosophy,” which, as “a fully conscious coproducer of IAE spam,” she endorses.20 Then Steyerl takes up the general form of Spamsoc, her term for the broken English that is everywhere on the internet, the speech of the ESL multitude as well as of bots and avatars, translation programs and phishing scams. If we could only read this dialect of a novice underclass with sympathy, Steyerl suggests, we might better understand the global tensions around language and culture, intellectual property and gendered labor. Here again, she makes an avant-gardist call “to alienate that language even further,” which her texts often attempt to do, for good and for bad.21 “The writing seems almost as if it were toggling among browser tabs,” an otherwise positive profile of Steyerl in the New York Times opined, and sometimes she does verge on a kind of Wiki-crit in which fast prose sutures big jumps in argument.22 Maybe this is one fate of critical theory online, as the essay form adapts to an environment of hot takes and endless links. (Certainly her colleagues at e-flux journal, where a majority of her texts first appear, have done well to inject specific critiques of art, culture, and politics into the general logorrhea of the web.) Nonetheless, it is difficult enough to pass through the murky reason of alienated language in fiction (George Saunders is a master of this dark dialectic); it is harder to do so in criticism.

Steyerl views almost everything symptomatically, and this invites us to do the same with her work. Ultimately, her thinking is less dialectical than paradoxical: more than intensify contradictions, she likes to collapse them; rather than deconstruct a position, she likes to burst it like a bubble. Like Slavoj Žižek and Boris Groys, she cannot resist a philosophical joke or a rhetorical trick, and sometimes this leads her to oscillate between semi-paranoid projections and semi-cynical implosions (in a way that is reminiscent of the late work of Jean Baudrillard). Such criticism has a special knack for catastrophe, which it seems almost to crave. With enormous ambition, it challenges the culture of capitalism, but finally it is too in awe of this leviathan, which it regards as the sole engine of history, to do so effectively, and so it settles for the default position, which, as the saying goes, is to imagine the end of the world rather than the end of this system. In some ways, for Steyerl, the two are one, which is to say that the end is already upon us. Skeptical of “posts,” she nonetheless indulges in them: we are in a “post-period” where “post-democracy” is the rule, she tells us; we are the last flotsam in the great sea of historical debris.

Four decades ago, in the early years of postmodernist discourse, Jacques Derrida peppered fellow philosophers who adopted “the apocalyptic tone” with a series of questions:

What benefit? What seductive or intimidating bonus? What social or political advantage? Do they want to cause fear? Do they want to cause pleasure? To whom and how? Do they want to terrify? To make one sing? To blackmail? To lure into a going-one-better in enjoyment? Is this contradictory? With a view to what interests, to what ends do they wish to come with these inflamed proclamations of the end to come or the end already accomplished?23

These questions, slightly revised, seem salient again: Why this apocalyptic tone from critics on the Left when we are surrounded by hell-fire politicians on the Right?