“Defining the idea of sculpture,” Sarah Sze has asserted, “leads to breaking it down.”1 This principle has led her to contrive strange worlds out of familiar things. Her constructions are not simple like most found objects; at the same time, they are more orderly than most assemblages. They are also not typical installations—not pictorial scenes writ large that we view at a distance, or immersive spaces that subsume us environmentally—though they can offer both kinds of experience.2 Fifty years ago, faced with the question of what sculpture could be, Richard Serra adopted nonart materials like rubber and lead and conceived basic actions to perform on them. His wellknown Verb List (1967) reads in part: to roll, to crease, to fold, to store, to bend. Over twenty years ago, Sze also turned to unconventional materials—cheap products and everyday discards like Q-tips, safety pins, and bottle caps—and submitted them to particular procedures. Among the verbs (as conceptual as they are physical) that direct her work are: to select, to arrange, to build up, to break off, to connect, to disconnect, to calculate, to improvise, to model.

In discussing her work, Sze has stressed two other verbs: to value and to teeter. As for valuing, she saves, orders, and displays what is usually consumed, jumbled together, and thrown out. In this way her precise compositions of odds and ends prompt us to think not only about the vicissitudes of use value and the vagaries of exchange value but also about how things “perceived as aesthetically worthless” can be given “aesthetic value.”3 Although Sze traffics in an excess of objects, her essential operation is not the mimetic exacerbation of “the capitalist garbage bucket” that contemporaries such as Isa Genzken, Thomas Hirschhorn, and Rachel Harrison perform.4 In various ways, these artists take bad things and make them worse, exploding kitschy products and junk space from within, whereas Sze works from a wide array of generic objects, attending to them closely, at once specifying particular parts and composing general wholes. Fragile as elements and precarious as constructions, her intricate pieces encourage an attitude of care.5

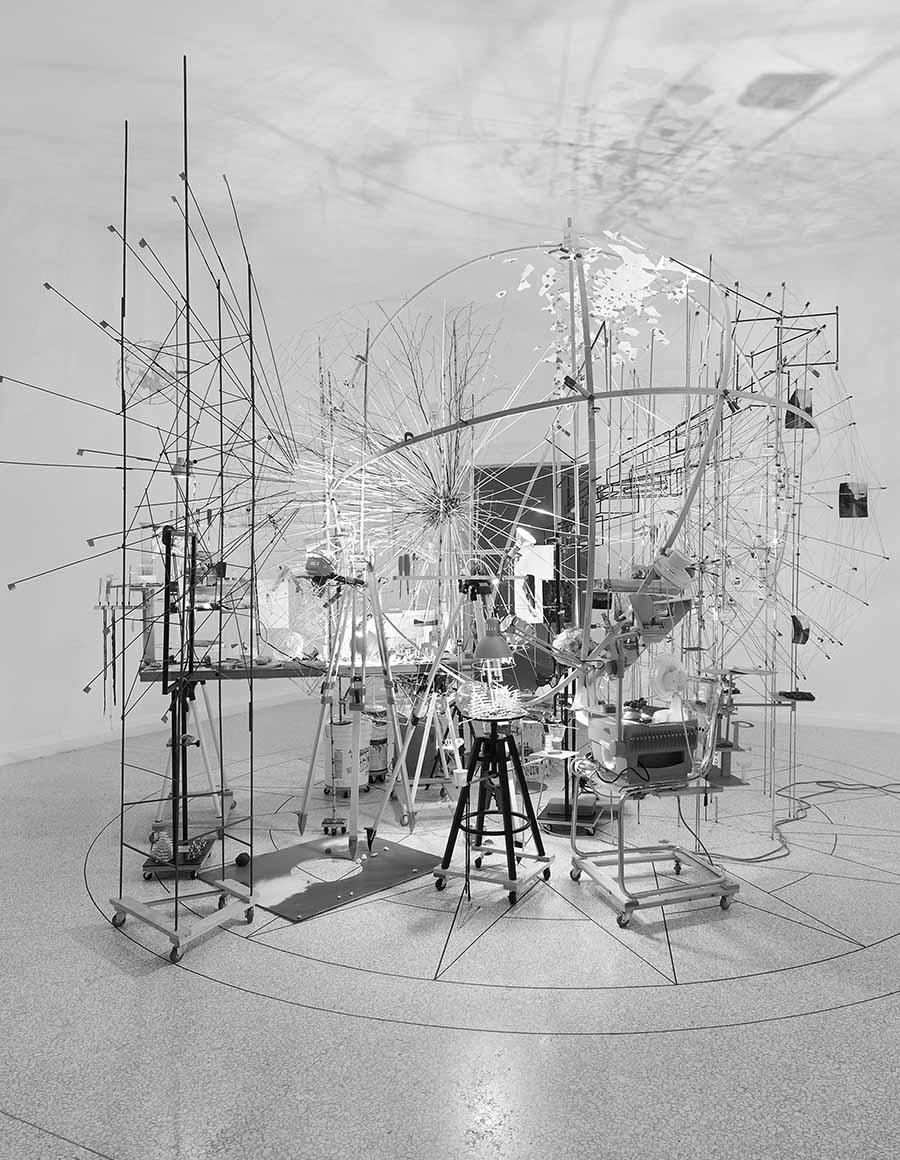

If this care of the thing suggests what Sze means by valuing, what might she intend by teetering? One clue is provided by the title of her exhibition at the 2013 Venice Biennale, Triple Point, which refers to a condition in which all three states of a substance—gas, liquid, and solid—coexist. “It’s this teetering between states” that Sze seeks, “the fragility of equilibrium, and the constant desire to create stability and a sense of place that frame the narrative.”6 Such teetering takes multiple forms in her art. It is active in how we move between the details of a piece and its composition as a whole, which is not strictly organic, mechanical, or electronic in association but often all three, evocative of a biotechnical fusion of these orders. It is also present in how we navigate between the interior and the exterior of her constructions, several of which produce a partial enclosure suggestive of a place of study, experiment, or observation. (This is announced in subtitles such as “studio,” “observatory,” and “planetarium.”) So, too, the teetering is scalar: all her pieces shift in focus from the tiny to the vast, from little webs of line here to the great circuit of an orrery there, and back again; we shuttle between the micro and the macro, the cellular and the stellar. And, often, the teetering is ontological as well: invited to investigate which of her objects are found and which are fabricated (Sze calls some “imposters”), we often struggle to distinguish between the real and the artificial. Finally, a teetering animates the composition of her pieces, which can appear both calculated and improvised. This is to say, too, that her art also teeters between order and disorder, homeostasis and entropy, autopoietic expansion and catastrophic collapse. “You don’t know whether it’s still in the process of being made or in the process of falling apart,” Sze states simply of her work.7 Why all this teetering? To what ends is this tension between equilibrium and disequilibrium put? A philosophy might be intimated here, one that sees life as a system that struggles with flux. At the very least this teetering keeps us on our toes, active and open, visually, bodily, and mentally, as each new piece asks us to solve a puzzle that is both perceptual and cognitive, and to do so in real time. In short, it renders us epistemologically alert, which is a value in its own right.

Sarah Sze, Triple Point (Planetarium), 2013, as displayed at the 2013 Venice Biennale. Wood, steel, plastic, stone, string, fans, overhead projectors, photograph of rock printed on Tyvek, mixed media. 20´’9˝ × 18´ × 16´6˝. © Sarah Sze, courtesy the artist and The Fabric Workshop and Museum.

“I’m interested in objects that have a dual identity,” Sze has said.8 This is a statement that can be understood in several ways. First, her objects are double. They are both individual elements—they are what they are, a fact that is never lost on us—and constitutive parts of a greater whole—they are what they make up, a general order that comes in and out of focus as we pass through a piece. Second, her things are double in that they are at once specific and generic, singular and serial, actual and metaphorical. Again, the particularity of the details persists even as they are subsumed into the pattern of the work. Significant here is that these various dualities invite us to reflect on the changed status of the everyday objects around us. Like many of her contemporaries, Sze acknowledges that the commodity is not only a primary reference of contemporary sculpture but also a pertinent ingredient in its making. Yet, as she arranges her materials, she does not simply restate the equivalence of the commodity form, but instead models an alternative world out of it. Nor does she simply decry the complete dominance of the spectacle, but instead plays with its scraps.9 In this way Sze manifests little of the frustration of some contemporaries (like Genzken and Harrison) and none of the nihilism of others (like Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst).

Our consumerist age is also marked by the becoming-image of the world, and Sze invites us to consider this condition too. An element in a piece, one as simple as a rock, might be ambiguous; we might not know whether it is found or fabricated. If it is painted to look like a rock, it carries its own representation on its surface—that is, it becomes its own simulacrum. Finally, we are sometimes surrounded by her things in such a way that they seem distorted by our presence.10 This double teetering—between thing and representation as well as object and subject—is the most troubling of all. In an initial stage of consumer capitalism, postmodernist art deconstructed the opposition of original and copy, which was already broken down in the economy at large, driven as it was by mechanical reproduction and electronic simulation alike. This is a simple problem compared with the one we confront today, in which myriad objects are produced as digital iterations, scalable in all dimensions. The contemporary version of the postmodernist conundrum of original and copy is this collapse of the distinction between thing and model. Sze picks up on this ontological trouble, plays with it, and invites us to puzzle it out as best we can.

Sarah Sze, Stone Series, 2013–15, as displayed at Victoria Miro, London. © Sarah Sze, courtesy the artist and The Fabric Workshop and Museum.

For a sculptor like Koons, size matters above all else; for Sze, scale is the essential concern. “It’s always shifting, sliding,” she comments; “it’s not static.”11 This shifting activates us as we view a work and guides us as we move through it. Like Serra before her, Sze found a model of this activation in the Japanese garden, which not only allows for teetering between focus on details and apprehension of the whole but also prompts a continuous movement through the topography of the work. In her constructions as in these gardens, “the viewer becomes a figure in the piece,” a figure with a stop-and-go rhythm; “the way the pieces are put together,” Sze adds, “is all about how someone speeds up or slows down, remembers or anticipates.”12 There are also uneasy moments in this passage, for often her constructions stage another kind of teetering, an uncertainty principle akin to the one central to quantum physics, whereby the observer, implicated in an experiment, complicates its results by her very presence. Sometimes, in similar fashion, we seem to be tested by her work as we observe it, an eerie feeling that Sze has associated with this poem by Emily Dickinson: “The show is not the show, / But they that go. / Menagerie to me / My neighbor be. / Fair play— / Both went to see.”13

How Sze involves her viewers prompts the question of how she relates to her sites. Typically, her constructions are not fully site-specific, that is, if we apply the litmus test, advanced by Serra in the controversy over his Tilted Arc (1981), whereby to move the work is to destroy it. Rather, they are site-sensitive, which is to say that her art adapts to its location but remains semi-autonomous within it, along the lines of a bird nest or a spider web that draws on its setting even as it produces its own structure. Sze has spoken of her sculptures as “actual systems” that “create weather” of their own: “there is air, light, a water system, and so on, within the piece itself.”14 The relation of her construction to its site is thus akin to the one outlined in the systems theory of Niklas Luhmann, for whom a system is distinct from the environment on which it depends to the extent that it is recursive in structure, even autopoietic in generation. “It’s about getting so deep into your work that it starts to tell you what to do,” Sze has remarked.15

In a key comment, the philosopher Arthur Danto once suggested to Sze that the role of the model in her art is less architectural than scientific, and, again, she has titled several of her works after places of experiment and observation.16 “Each piece,” Sze adds, “acts like a site of evidence of some behavior,” a setting where it can be studied and tested.17 This aspect has led her to describe her constructions as “habitats,” and sometimes they do appear to be produced by another species, perhaps an otherworldly avian forced to make an earthly nest out of the odds and ends of our Anthropocenic environment. In these instances, Sze evokes the Umwelt of an alien intelligence, a paradoxical world-making in which, even as the effects of the human appear pervasive, the efficacy of the human, our human agency, seems diminished.18 But then such is our habitat in the present, at least to the extent that we are subsumed into systems that seem beyond our control. As the media theorist Alexander Galloway has argued, digital networks oscillate between two modalities, one that he calls “the chain of triumph,” which allows for an interconnectivity that is “linear, efficient and functional,” and one that he terms “the web of ruin,” which captures our data as we communicate through it, and so “ensnares [us] in the very act of connection.”19 This fatal ambiguity (it might be too optimistic to call it a dialectic) is evoked in several Sze structures, in which the utopian dream of imaginative construction and rapport (the chain of triumph) confronts the dystopian fact of commodification and control (the web of ruin).20

There is, however, an alternative way to view this ambiguity. Another touchstone for Sze is the Borges story “The Analytical Language of John Wilkins,” which tells of a “certain Chinese encyclopedia entitled ‘Celestial Empire of Benevolent Knowledge’”: “In its remote pages it is written that animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.”21 This is the encyclopedia taken up by Michel Foucault in The Order of Things (1966) as an absurd tabulation that undoes the very order that any typology is supposed to provide. In his own gloss, the Borges narrator agrees with this assessment, at least in part: “It is clear that there is no classification of the universe not being arbitrary and full of conjectures. The reason for this is simple: we do not know what thing the universe is.” At the same time, he is more sanguine than Foucault about the ramifications of this arbitrariness: “The impossibility of penetrating the divine pattern of the universe cannot stop us from planning human patterns, even though we are conscious they are not definitive.”22 Sze seems to concur: although she speaks of “impossible systems of information” and “ultimately futile projects,” this does not deter her from her proposals for calendars, orreries, encyclopedias, and the like.23 In her versions, these old systems might fail—they might falter, stop abruptly, or simply break down—but she does not celebrate the failure. Unlike many postmodernist artists of a previous generation, Sze is on the side of symbolic totality, not allegorical fragmentation, on the side of utopian aspiration, not dystopian despair.24

What counted as science in one period is often taken as myth in the next, and it might be productive to see Sze in this anthropological light too. “Mythological worlds have been built up, only to be shattered again,” the ethnographer Franz Boas once remarked, and “new worlds were built from the fragments.”25 In his own account of myth (which draws on Boas), Claude Lévi-Strauss conceived this rebuilding as a matter of bricolage. The bricoleur, he writes in an influential definition, “makes do with ‘whatever is at hand’”; in contradistinction to the engineer, she works with “a collection of oddments left over from human endeavors.”26 Although the bricoleur is sensitive to the facticity of her materials, she treats them as “intermediaries between images and concepts,” that is, as signs in which “the signified turns into the signifying and vice versa,” even as “operators” that “represent a set of actual and possible relations.”27 So it is with Sze: with objects and images that are both found and fabricated (and often held together with everyday tools such as blue tape and glue gun), Sze builds new worlds from old fragments.

For Lévi-Strauss, myth is an imaginary resolution of a real contradiction, that is, its narrative works over social conflicts that cannot be resolved in actual life.28 For the Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser, this is exactly what ideology does as well: it offers imaginary resolutions to real contradictions.29 In keeping with her critical spirit, we might ask Sze whether there is an ideological dimension in her own art. Benjamin Buchloh has offered this astute synopsis of her work: “Incessant shifts, from tectonics to semiotics, from tactile to syntactic, from enacted gravity and phenomenology to enforced simulation of mere surfaces and signs, appear to be the parameters of Sze’s sculptural models of contemporaneity.”30 This suggests that such shifting, such teetering, might assuage some of our own cultural discomforts. The question then becomes: does Sze demonstrate or aestheticize, model or mystify, the vicissitudes of electronic dematerialization, the web of ruin laid down by digital networks, the ontological breakdown of the distinction between thing and model? Might she offer up too much “social life” to her otherwise inanimate objects? Might she render her materials too “vital” and “vibrant”? In short, what is the relation of her object-oriented aesthetic to our biotechnical Anthropocene?31 The fact that her art prompts such questions so keenly, ones crucial to our contemporaneity, is central to its achievement.