Chapter 15

Galactic Evolution

Soon after the Big Bang, dark matter provided a gravitationally lumpy stage into which normal matter, hydrogen and helium, eventually flowed. As this gas continued to cool, these vast supercluster-scale clouds fragmented into smaller cloudlets. Some of these cloudlets were the size of modern dwarf galaxies with masses of about 1 billion times the Sun’s mass. As cooling continued, enormous populations of Pop III stars of 100 solar masses or more were able to gravitationally condense and explode within a few million years. This material, now enriched with some heavy elements, mingled with the existing gases to form the plenum out of which newer generations of stars could form. These became the Pop II stars we see today.

These Pop II stars formed within smaller dark matter gravity wells that became the halos for most modern-day galaxies. This process was so rapid that entire massive elliptical galaxies formed within a billion years after the Big Bang. Some of these formative events involved the cannibalism of smaller galaxies, in the same way that in 2 billion years our Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies will collide and merge to become a giant elliptical galaxy.

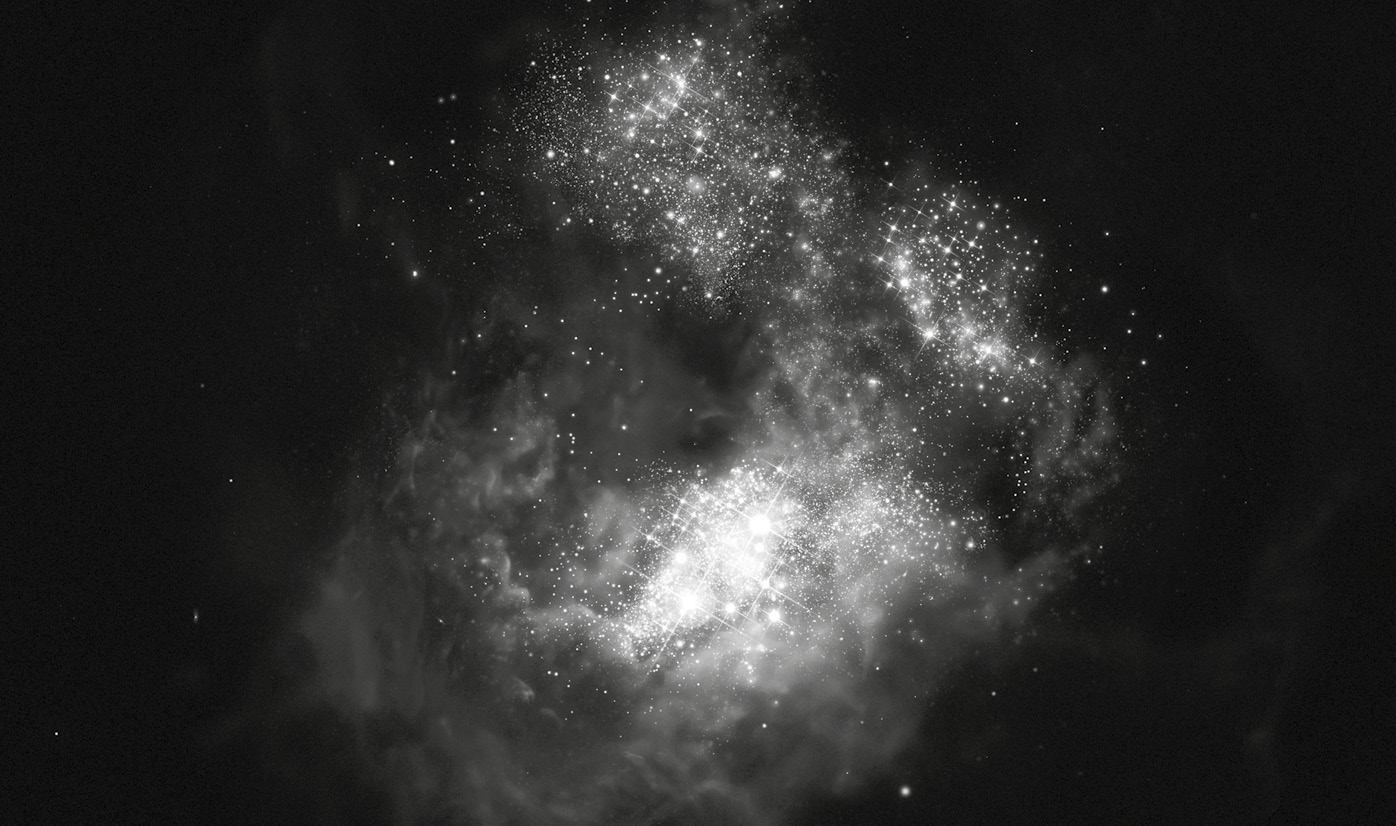

This artist’s impression shows CR7, a very distant galaxy discovered using ESO’s Very Large Telescope. It is by far the brightest galaxy yet found in the early universe and there is strong evidence that examples of the first generation of stars lurk within it.

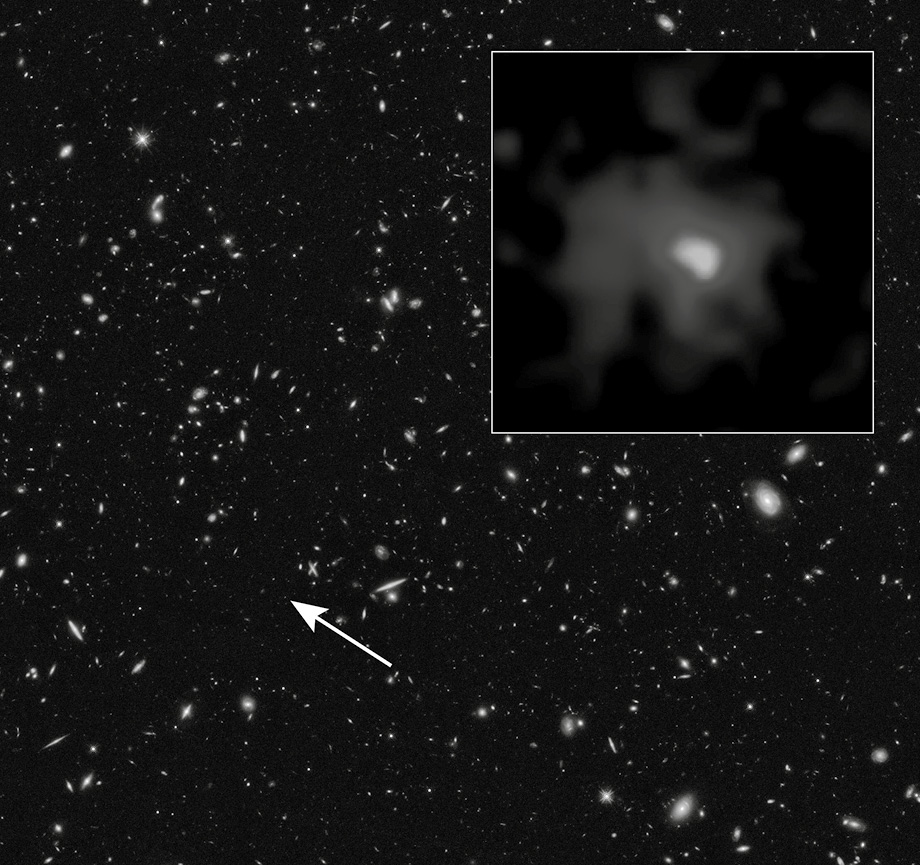

The infant galaxy EGS-zs8-1 is 13 billion light years distant and is phenomenally bright for its age. It has already achieved more than 15 per cent of the mass of our own Milky Way, but it had only 670 million years to do so since the Big Bang.

Some smaller dwarf galaxies, with masses of less than 1 billion suns, remained independent systems. They experienced multiple bursts of rapid star formation, leading to Pop I stars with nearly solar levels of elements, as early as 1 billion years after the Big Bang. The star formation rate in these galaxies was so rapid that they appear blue as they shine with intense ultraviolet light. Across the universe, these very numerous galaxies produced so much ultraviolet light that they reionized much of the cold, dark hydrogen gas in the intergalactic medium, marking the end of the dark ages and the beginning of a more transparent universe. This happened about 150 million to 1 billion years after the Big Bang. Not all the hydrogen gas became ionized at once. Numerous dark clouds lingered, some containing near-galaxy-sized masses. These clouds can be detected in the light of distant quasars as specific absorption lines seen in the spectra of hydrogen gas. Quasars are remote and highly energetic celestial objects, thought to contain massive black holes. Star formation in the dwarf galaxies contributed more than 50 per cent of the ionizing UV light because this light had an easier time escaping from these smaller collections of mass.

Galaxies did not form in isolation but were often in groups whose memberships changed through cannibalism. The speed at which galaxies and clusters of galaxies formed is considered remarkable by astronomers. The farthest and youngest galaxy cluster identified today consists of four quasars found in a common cloud of hydrogen gas 1 million light years across located 10.6 billion light years from Earth. Its distance corresponds to a cosmic age of 3.2 billion years since the Big Bang. We only see the bright quasar cores of the host galaxies.

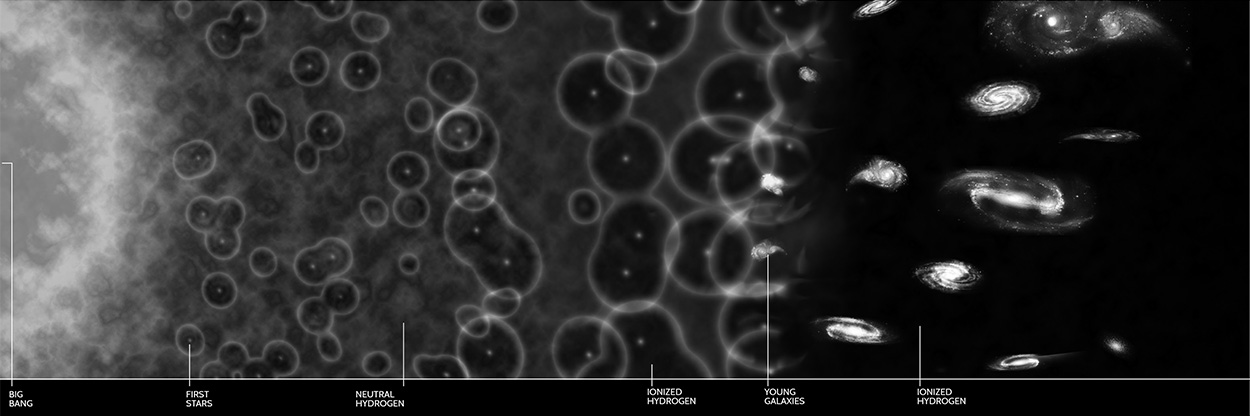

During the Reionization Era, massive ultraviolet stars converted the dark hydrogen clouds into a dilute ionized plasma, first through the emissions from individual Pop III stars (left), then through the combined star-forming activity in numerous dwarf galaxies (right).

Supermassive Black Holes

Black holes can grow by absorbing material such as stars, ISM and even other black holes. In the dense cores of galaxies there are plenty of sources of infalling matter. Our Milky Way has a supermassive black hole containing over 4 million times our Sun’s mass, which would imply a growth rate of about three solar masses every 10,000 years. This is dwarfed by the supermassive black hole at the core of the supergiant elliptical galaxy NGC 4889, which is 21 billion times the mass of our Sun at a distance of 308 million light years in the Coma Cluster. This would require a growth rate of 1.5 solar masses every year. Our Milky Way is barely considered an active galaxy based on the brightness and activity of its nuclear volume. However, NGC 4889 would be a quasar-level galaxy if it were currently being fed at this mass rate.

The favoured method for forming supermassive black holes rapidly is through mergers of galaxies. These black holes can grow to billions of solar masses by consuming local matter. But collisions allow black hole mergers that dramatically increase their growth rates. The most distant supermassive black holes, and therefore the youngest in cosmic age are the hyper-luminous quasar S50014+81 with 40 billion solar masses at 12.1 billion light years distance and TON 618 with 66 billion solar masses at 10.4 billion light years distance. These two supermassive black holes push the idea of growth-by-mergers to what are considered to be ridiculously high levels and possibly imply that a new mechanism must be considered. Nevertheless, the discovery of binary supermassive black holes in the merging galaxy 4C+37.11, each with a mass of about 15 billion suns at a distance of 750 million light years, continues to support this formation model. The quasar OJ 287 at a distance of 3.5 billion light years has a massive black hole with 18 billion solar masses being orbited every 12 years by a smaller black hole with a mass of about 100 million suns, so black hole mergers do occur at many cosmological epochs.

Active Galaxies

Radio Galaxies

The detection of radio emissions from the Milky Way by Grote Reber in 1944 opened up a new window to the universe. Since then, many new and more sensitive ‘radio telescopes’ have been constructed. In addition to the radio emissions from the Milky Way, which could now be mapped in great detail, numerous ‘radio stars’ were also discovered. Many of these were not merely points of radio emissions in the sky, but could be resolved and mapped using radio ‘interferometers’ (see pages 14–15) in which two or more radio telescopes are combined across continents to detect detailed structure and form in celestial radio sources.

The Hercules A galaxy. Radio emission highlights the massive double jets. The visible light image shows the central host galaxy and other background galaxies.

One of the most powerful extra-galactic radio sources, Cygnus A (also called 3C 405), is a double radio source located some 600 million light years from the Milky Way in which the dumbbell-shaped pair of ‘lobes’ are separated by about 500,000 light years. Moreover, from photographic searches with the Mount Palomar 5 m (200 in) telescope, the centre of this radio source was found to coincide with a distorted pair of distant colliding galaxies.

In a growing number of cases, optical candidates could be found for these radio sources in which a single large radio source appeared offset from the optical object. In several cases, such as Virgo A (M-87), an optical ‘jet’ of light could be seen emanating from the galaxy’s nucleus in the direction of one of the radio-emitting lobes. Not only that but over time and at high resolution, individual plasma clouds (called plasmons) many light years across could be seen travelling down the jet as though being ejected from some invisible source at the base of the jet, in the core of the host galaxy. The speeds of these plasmons have been measured to be large fractions of the speed of light, making them among the fastest physical phenomena seen in the universe.

Quasars

As optical searches of radio sources continued, one object called 3C48 was discovered in 1963 by astronomer Alan Sandage to have merely a faint star-like blue object at its centre. Astronomers Jesse Greenstein and Thomas Matthews were able to obtain a spectrum for this object and discovered that its lines made no apparent sense. The same year, Maarten Schmidt and Beverly Oke detected the optical counterpart to 3C273 and their spectroscopic work indicated a ‘redshift’ of z=0.16, which means a recession speed of 16 per cent that of the speed of light. It was Schmidt who correctly interpreted the wavelength shift as normal atomic lines displaced to longer wavelengths due to cosmic expansion. It was now possible to understand the earlier spectrum of 3C48; if the spectrum wavelengths were shifted to the red by about 37 per cent it implied a recession speed of nearly 110,000 km/sec. The term ‘quasar’ was coined by astronomer Hong-Yee Chiu in May 1964.

The hunt was now on for more quasars, leading to a catalogue of about 40 examples by 1968. Today, more than 200,000 quasars are known – most identified from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. All observed quasar spectra have redshifts between z=0.056 and z=7.085. Applying Hubble’s law and general relativity to these redshifts, it can be shown that they are between 600 million and 28 billion light years away (in terms of their actual cosmological distance). Because of the great distances to the farthest quasars and the finite velocity of light, they and their surrounding space appear as they existed in the very early history of the universe. The most distant known quasar, J1342+0928, is at a redshift of z =7.54 and existed when the universe was only 700 million years old. We are seeing the light from this object when the first stars and galaxies were forming in the universe.

By plotting the number of quasars at each redshift, astronomers have identified an Era of Quasar Formation that occurred between redshifts of z=0.5 and z=3.0, corresponding to a period about 2 to 5 billion years ago. Today, the formation mechanism for quasars appears to be less effective than it once was, so fewer examples exist in our part of the universe. In fact 3C273, with a redshift of z=0.16, remains the closest known quasar at a distance of 2.4 billion light years. Its luminosity amounts to over 4 trillion stars like our own Sun. Even so, it is not the most luminous quasar known. The quasar SDSS J0100+2802, discovered in 2015 at a redshift of z=6.3, produces 430 trillion times the light energy of our Sun, and we see its light when the universe was only 900 million years old.

In addition to quasars, and since the 1960s, a bewildering ensemble of peculiar galaxies have been discovered. Many show indications of activity in their dense nuclei. Studies of these ‘active galaxies’ at a variety of wavelengths from the radio and infrared to X-ray frequencies reveal three separate types of activity.

Starburst galaxies

These galaxies show indications of large numbers of massive stars being formed in a short span of time, and also evidence of many supernova events as some of these massive stars end their lives.

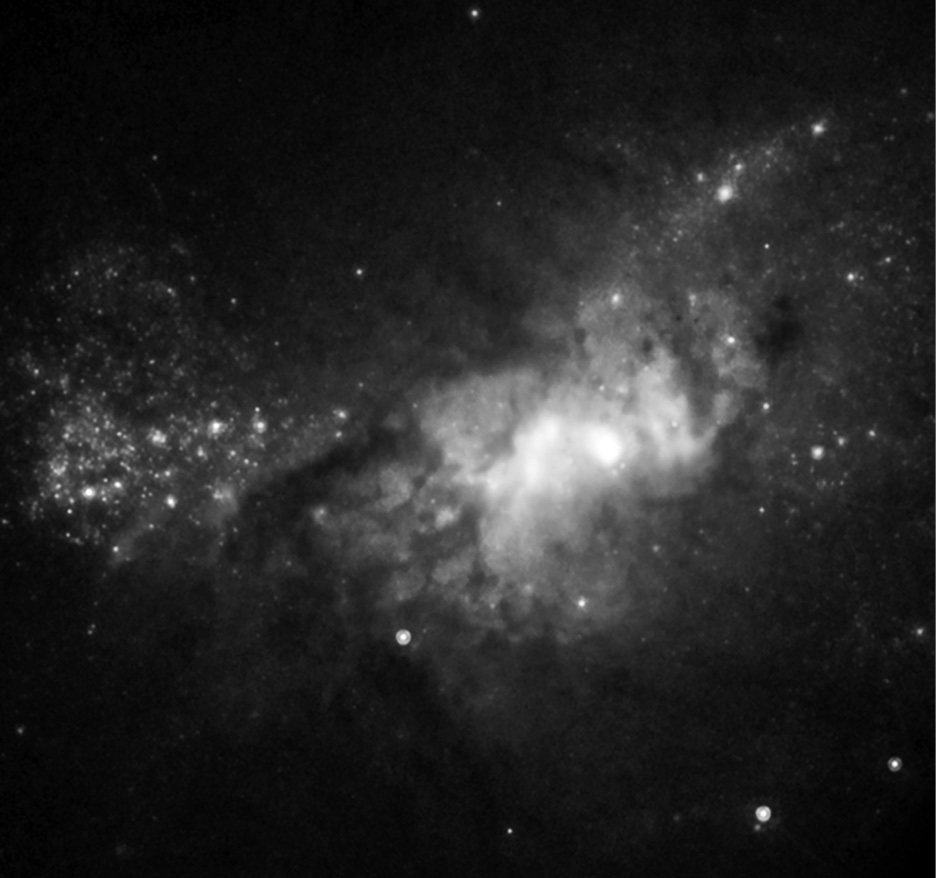

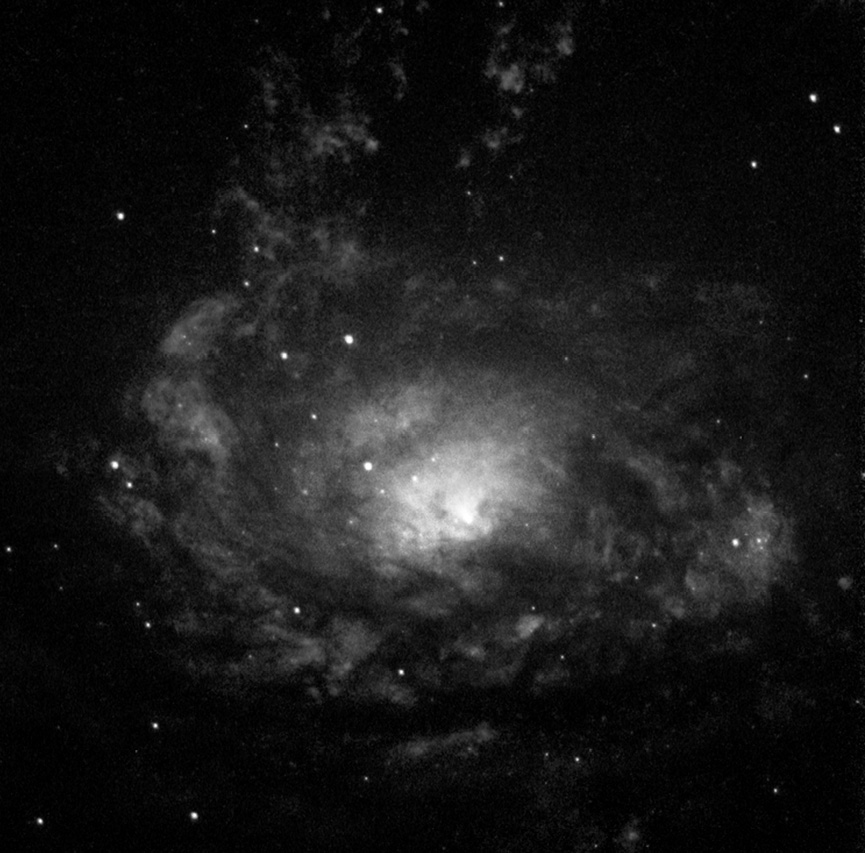

The starburst galaxy Henize 2-10 showing complex star formation and gas ejection.

Seyfert galaxies

These galaxies are powerful, compact sources of radio and infrared radiation usually found in the cores of spiral-type galaxies. Their nuclei often contain ionized gas travelling at thousands of km/s as though expanding from some central source that has ejected these clouds.

The Circinus A seyfert galaxy showing bright nucleus and complex gas flows feeding a supermassive black hole at its centre.

BL Lacertids and Blazars

These objects are galaxies with bright star-like cores that vary in optical and radio brightness over the course of months or years. The first galaxy of this type was actually misidentified as an ordinary variable star in the Milky Way and designated BL Lacertae. Blazars are even more variable on timescales as short as hours, and also produce gamma-rays.

Studies of active galaxies have found that many are associated with colliding galaxies in which violent collisions between interstellar clouds provide the stimulus for forming numerous massive stars. For other active galaxies, such as the Seyferts and BL Lacertids, it is thought that they represent a common process but viewed at different perspectives from Earth. These galaxies have massive black holes at their star-like cores, which are consuming matter from a surrounding accretion disk. Viewed edge-on you see a Seyfert-like phenomenon, but viewed face-on you are looking down the axis of a high-speed jet of plasma that changes its brightness rapidly to produce the ‘BL Lac’ and Blazar phenomena.

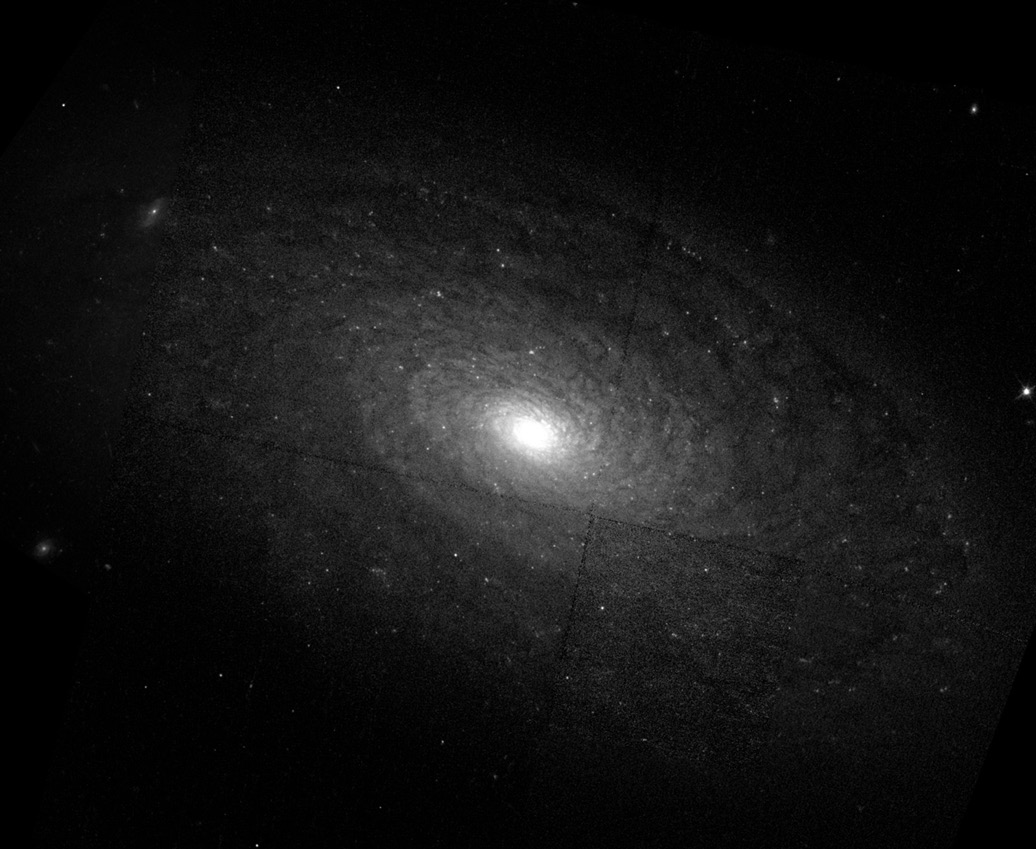

The BL Lacertid-type galaxy NGC 4380 with classic star-like nucleus.

Key Points

• The earliest stars that formed in the universe were made of pure hydrogen and helium and typically had masses greater than 100 suns. These Pop III stars supernovaed and spread enriched elements throughout the universe.

• Over time, galaxies formed massive central ‘supermassive’ black holes due to mergers and galactic cannibalism.

• The feeding of these supermassive black holes led to a variety of activity in galaxies including quasars, which were common in the universe but very rare today.

• The evolution of galaxies is driven by collisions with their neighbours that can lead to cannibalism and mergers, and also trigger the feeding of central supermassive black holes.

• It is believed that galaxies formed within the first 100 million years after the big bang, and grew steadily in size through mergers among smaller-massed objects.