Chapter 18

The Dark Universe

Until the discovery of extra-galactic nebulae, the essential ingredients to the universe were considered to be the luminous stars. The distances to many of the nearby galaxies were determined by Edwin Hubble in the late 1920s. For cosmological discussions, these were the farthest outposts of luminous matter in the universe, spreading out to the limits of telescopic sight.

The discovery of the interstellar medium (ISM) during the first-half of the 20th century, first by optical means and then by its radio emissions, showed there was more cosmic matter than the stellar galaxies alone. Through its radio emission at the 21 cm (8½ in) wavelength of the ‘hydrogen line’, the ISM was carefully mapped throughout the Milky Way and other nearby galaxies, but the amount found therein was seldom more than 10 per cent of the total mass of the host galaxy as measured by their stellar content. This cold ISM, however, was also a companion to a hot ISM of ionized hydrogen and other common elements that could not be seen via the neutral atomic hydrogen emission. X-ray telescopes would detect this emission as a diffuse glow permeating some sectors of the Milky Way where supernova remnants had recently blasted their way through the neutral ISM and ionized it. Nevertheless, estimates of the total mass that could reside in this ISM was also a small percentage of the total galactic mass.

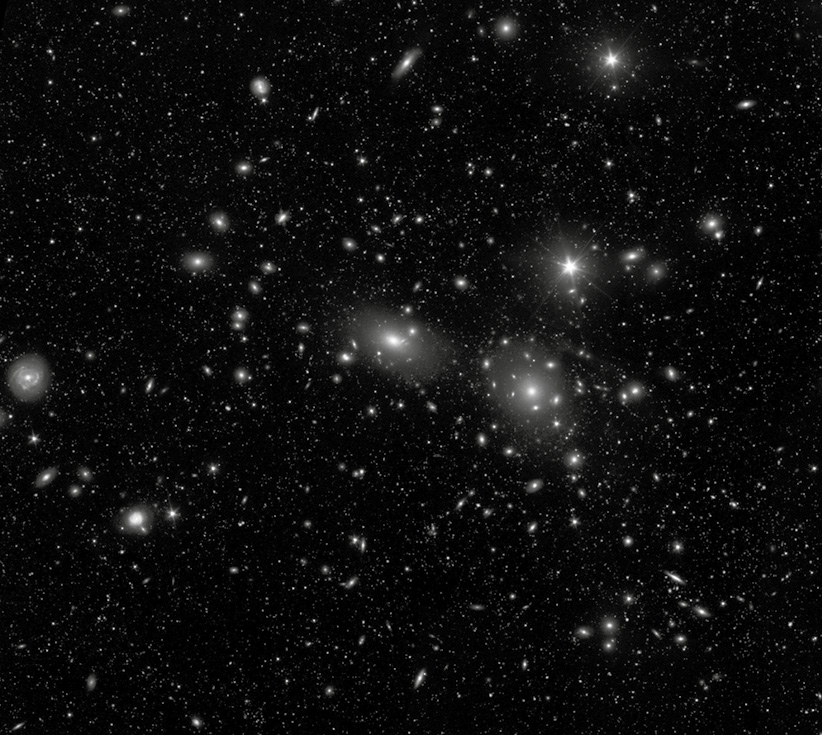

Image of the core of the Coma Cluster revealing hundreds of individual galaxies clustered together within a volume of space only 10 million light years across.

In 1933, CalTech astronomer Fritz Zwicky made the startling announcement that the Coma cluster of galaxies was hiding a considerable amount of mass, far beyond the small contributions of interstellar gases. Not only did Coma have this ‘missing mass’ problem, but several other clusters of galaxies had the same deficit.

This startling finding came about when Zwicky determined the velocities for eight galaxies in the Coma cluster whose actual membership includes over 1,000 galaxies. He discovered that the range of speeds for the galaxies in the Coma galaxies was ±360 km/s. This implied a mass for the cluster, assuming these eight galaxies were typical, that would be over 50 times more than the mass one would determine from the luminous matter in the galaxies themselves. According to Zwicky, ‘If this [overdensity] is confirmed we would arrive at the astonishing conclusion that dark matter is present [in Coma] with a much greater density than luminous matter.’ Three years later, Sinclair Smith discovered the same effect in his study of 32 members of the Virgo cluster.

On the galactic scale, investigations of the nearby Andromeda Galaxy by Horace Babcock in 1939, subsequent studies by Vera Rubin and Kent Ford in 1970, and radio astronomers Morton Roberts and Robert Whitehurst in 1975, found that the outer regions of this spiral galaxy beyond the bright stellar disk also revealed a ‘dark matter’ problem. By measuring the rotation speed of a spiral galaxy at various distances from its luminous core, this ‘rotation curve’ should have a very distinct shape once you reach the limits to the galaxy’s stellar disk. The relationship is given by Kepler’s Third Law, and is illustrated by the dashed line in the diagram (left) on Messier-33.

Rotation curve of Messier 33 showing that the speed of the stars and interstellar gas (top curve) exceeds the speeds predicted if all the mass were located within the visible galaxy (bottom dashed curve).

What the rotation curve actually represents is a way to measure the total mass of a galaxy inside the selected radius. If all the mass is largely confined to the bright nuclear region, the curve should reach a maximum, and then the speeds should decline from that point outwards. This was not found for the Andromeda Galaxy and a number of other carefully studied systems. To account for these flattened curves, the galaxy must contain large quantities of dark matter far greater than the mass found in the luminous stars. Our own Milky Way also shows evidence for dark matter.

Vera Rubin was an astrophysicist at the Carnegie Institute in Washington DC where she worked on investigating the rotation curves of galaxies, wishing to avoid in the late 1960s the controversial topics of Milky Way structure and quasars while working with astronomers Margaret and Geoffry Burbidge. Her investigations of ‘normal’ galaxy rotation turned up anomalies that led her to the discovery of dark matter in individual galaxies, which dramatically improved the detection and characterization of this hidden, gravitating component to the universe.

The origin of this dark matter has been a matter of intense speculation since the 1960s. Candidates have included neutrinos with large masses, dim dwarf stars, black holes and even large numbers of planetary-sized objects. The problem has been that the dark matter mass distribution suggests that the average density of dark matter in the Milky Way is about 10 times that of stellar sources, so we should see plenty of evidence for this material among the stars in the solar neighbourhood. No such dark material or objects have yet been found.

At the present time, the best model for dark matter in the Milky Way involves studying the detailed speeds and distances of nearby galaxies and the Magellanic Clouds. From this, the Milky Way can almost literally be ‘weighed’. The result is that about 95 per cent of the galaxy is composed of dark matter. The luminous matter makes up approximately 3×1011 solar masses. Recent observations by the Gaia satellite of the motions of globular clusters along with Hubble Space Telescope observations leads to a total gravitational mass for the Milky Way of 1.5 trillion solar masses out to a distance of about 130,000 light years. Most of this mass is dark matter within an extended halo, and within which the 160 globular star clusters and stars in our Milky Way exist as a flattened, spiral disk.

An artist’s rendering of the Milky Way dark matter halo based upon a variety of techniques for measuring the speeds of nearby galaxies and their gravitational accelerations towards the Milky Way.

Cosmological Dark Matter

The discovery of large quantities of dark matter in the halos of individual galaxies and in clusters of galaxies had immediate cosmological consequences. The maps of the minute fluctuations in the CMBR provided by the NASA COBE mission suggested a weakly clumpy universe by about 360,000 years after the Big Bang, but when these irregularities were evolved forward in time to the present era using only the gravity of the known luminous matter, the clustering was too weak to account for what is seen today. This led to, or was contemporaneous with, various mathematical experiments to account for the clustering today by adding-in hot dark matter (HDM) and cold dark matter (CDM). The former would be in the form of a very hot gas that would not be directly detectable, the latter would be a colder form of material. Generally, the current structure could not be accounted for unless the missing mass found in galaxies and clusters of galaxies was cosmological in extent. In addition, if this added material were in the form of baryons (sub-atomic particles such as protons and neutrons), it would upset the calculations of the abundances of the primordial elements. Physicists called this material, proposed in the 1970s, weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPS). Other forms of dark matter based upon dark stars, black holes and other dense dark forms of baryons were called massive compact halo objects (MACHOS). However, the addition of these baryons would also upset the observed ratios of the abundances of primordial elements.

The NASA WMAP spacecraft launched in 2001 was instrumental in providing a refined and high-resolution (0.2o) look at the CMBR, and from this new data, a precise inventory of the gravitating material in the cosmos was first obtained. When the data was analysed through the cosmology of a Friedmann universe with a cosmological constant, Λ, and CDM, the final high-precision values for our Λ-CDM universe were obtained.

• Our universe is 13.77 billion years old.

• The geometry is within 0.4 per cent of being as flat as Euclidean space.

• Baryonic matter accounts for 4.6 per cent of the gravitating material in the universe.

• Non-baryonic ‘matter’ accounts for 24 per cent of the gravitating material in the universe.

• There is a ‘dark energy’ (Λ) component amounting to 71.4 per cent of the material in the universe.

With this new high-precision data, and a confirmation of the accuracy of the Λ-CDM cosmological model, it was now possible to run detailed supercomputer simulations to explore how this dark matter and energy affected the way that baryonic matter clumped and clustered as the universe aged to the present time.

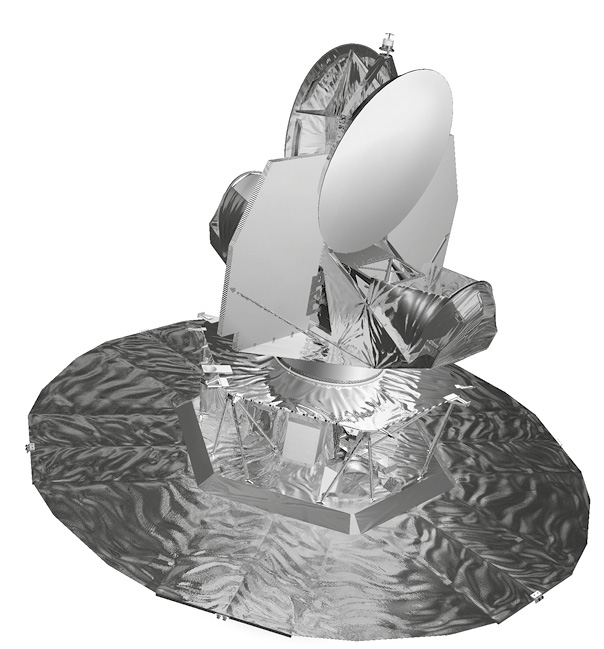

The NASA WMAP spacecraft used a sophisticated version of the COBE DMR instrument to map the CMBR at high resolution, and made high-precision measurements of dark matter and dark energy.

Preliminary supercomputer simulations were begun in the 1970s with programs that followed thousands of mass points in an evolving universe. By 1990, this number had jumped to simulations involving one million ‘galaxies’. By 2000 over 100 million galaxies were simulated in such massive supercomputer efforts as the Millennium Simulation Project in 2005, and the Bolshoi Simulation in 2012. Most recently, in 2018, the Illustris Next Generation simulation at the High-Performance Computing Center Stuttgart, Germany has followed the formation from 30 billion cosmic gas elements as they form one million galaxies in a volume of space one billion light years across. The simulation takes two months and generates over 500 terabytes of data. From this simulation, the exact behaviour of dark matter interacting with normal matter can be followed through the formation of large cosmic structures and the halos of individual galaxies. Even the formation of supermassive black holes and their effect on surrounding galactic matter can be followed.

On the galactic scale, it is now possible to use clusters of galaxies and gravitational lensing (see page 24) to map out where the dark matter is located in a number of clusters. The most famous of these is the Bullet Cluster. When these two clusters of galaxies collided, the dark matter was not affected and moved with the galaxies, but the gas (baryons) was left behind and formed shock-heated plasma. This demonstrates that dark matter only interacts through its gravity and cannot be detected by electromagnetic means (light, radio, X-rays). In this instance, it was detected by its gravitational lensing of background galaxy images.

Supercomputers are now powerful enough to simulate the growth of clustering in the evolving universe. The 2012 Bolshoi simulation with dark matter included matches almost exactly the observed statistical clustering of galaxies seen in the Sloan survey of one million galaxies.

Simulation of a 1.2 billion light year region of baryonic matter forming cosmic structure with dark matter included.

Cosmological Dark Energy

Among the other findings by the WMAP study of the CMBR was that a significant amount of ‘dark energy’ also coexisted with the dark matter and baryons in our universe. This dark energy behaved like the cosmological constant introduced in the early 20th century by Albert Einstein and Willem de Sitter and is historically represented by the Greek letter Λ. The implication of a non-zero Λ was staggering but not entirely unanticipated.

For decades it had been automatically included in modern Big Bang cosmological models because it was deemed another factor in the theory that had to be proven to not exist through the uses of observational data. Generally, its magnitude was considered unmeasurable by most studies. In 1998, the first true signs of this cosmological factor were discovered by two teams of researchers who used Type 1a supernovae as ‘standard candles’: the Supernova Cosmology Project led by Saul Perlmutter at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, and the High-Z Supernova Search Team led by Adam Reiss from Johns Hopkins University. These supernovae, produced when a white dwarf orbiting a star explodes, should theoretically all have about the same peak luminosity because the white dwarf stars have about the same masses (1.44 solar masses). When a distant supernova is identified as a Type 1a supernova, its apparent brightness can be related to its true peak brightness, and a cosmological distance determined. When this was done for several dozen supernova, they were found to be much farther away than their cosmological distance implied. A number of explanations were tried for this effect, including dust near the supernovae and white dwarf masses not being exactly the same, but none could easily explain this effect. The simplest explanation became that our universe in recent time has started to accelerate in its expansion.

The Origins of Dark Matter and Dark Energy

Currently there are candidates for dark matter including a new family of particles called neutralinos predicted by some versions of supersymmetry theory – the next step beyond the Standard Model. Intense experimental work has been in progress for over a decade to detect these particles, but to no avail by 2019. As for dark energy, its behaviour is similar to what would be expected for a new quantum field in nature, possibly related to the Higgs boson or the hypothetical Inflaton boson, which triggered the inflation of the universe (see page 214). Just as for dark matter, there are no candidates for this new field of nature that have been experimentally identified.

The accelerated expansion of the universe from supernova data reveals that about 9 billion years ago dark energy began to overtake the normal expansion rate predicted by standard Big Bang cosmology without a ‘cosmological constant’.

Key Points

• Early studies of how galaxies rotate by Vera Rubin suggested that large amounts of ‘dark matter’ must be present, but not in the form of stars or interstellar gas.

• Studies of clusters of galaxies by Fritz Zwicky discovered that galaxies are moving far too fast within these clusters for them to be gravitationally bound, and so dark matter was needed on vast scales to stabilize them.

• Observations of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation by the COBE and WMAP spacecraft established that 4.6 per cent of the universe is ordinary matter but that 24 per cent is in the form of dark matter.

• Dark matter dominates the structure of the universe on its largest scales and defines the filamentary shapes of the clustering of galaxies on scales of 100 million light years or larger.

• Dark energy accounts for 71.4 per cent of the cosmos and is responsible for the accelerated expansion of the universe. Its origin is currently unknown.