Chapter 3

Mathematics and Theories

There has never been a time when mathematics has not been an integral part of the human process of understanding the cosmos, whether it is the arithmetic Venus-sighting calculations of the ancient Babylonians, or the intricate geometric designs by ancient Greek astronomers such as Ptolemy. Astronomy has always been an observational, data-driven science, and for quantitative data in numerical form, there is no better way to organize it and extract meaning from it than through logical and mathematical manipulation.

The dramatic increase in measurement capability provided by Tycho Brahe led to much higher quality data, and it was no longer adequate to model planetary orbits as concentric circles. By the early 1600s, Johannes Kepler’s First Law derived from the new data was that planets orbit the sun on elliptical orbits. His ‘Third Law of Planetary Motion’, stated as the period-squared is proportional to the distance-cubed or T2 = A3, also required an algebraic approach to analysing the data rather than a more cumbersome geometric one.

Johannes Kepler discovered three laws of planetary motion which have proved essential to our understanding of astronomy.

Newton and Gravity

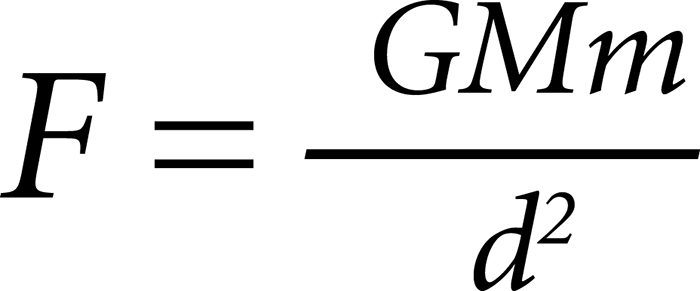

The next major change in how astronomers worked with astronomical data and its mathematical modelling occurred almost single-handedly at the hands of Sir Isaac Newton in 1666. Newton, working with the ideas developed for mass, velocity, acceleration and force by Galileo Galilei in the 1640s, took these ideas and developed a detailed mathematical framework for motion under the influence of his Universal Law of Gravity stated simply as

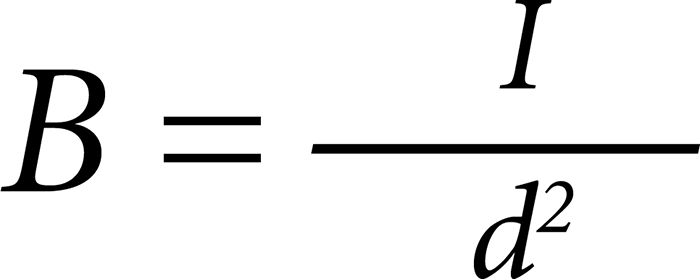

His book Principia, published in 1687, is considered one of the greatest mathematical tours de force in physics, laying out many new laws and principles in algebraic fashion. In it, he not only described how gravity operates but discussed and calculated tidal influences and planetary orbits, the precession of the Equinoxes and the orbit of the moon and invented a whole new form of mathematics we now call the calculus, or as Newton called it ‘The Method of Fluxions’. Later in 1680, Robert Hooke mentioned to Newton that he believed without proof that the inverse-square law for gravity led to elliptical planetary orbits. The inverse-square law in optics describes how the brightness, B, of an object decreases as the distance to the observer, d, increases according to the simple formula

so that if you double the distance, the brightness decreases by a factor of 4. Newton showed that the same diminution law also applies to gravity. Newton took Hooke’s proposal as a challenge and quickly proved this basic fact as a natural result of his Law of Gravity acting between the planet and the sun.

The transition from simple algebra being used by Kepler to formulate the laws of planetary motion, to Newton’s deep-dive into mathematics to account for the detailed motions of bodies under the influence of gravity, set the stage for many more centuries of merging mathematics with expositions of why things happen the way that they do. Mathematics increasingly provided a new ‘telescope’ with which astronomers could understand seemingly implacable discoveries made through their telescopes and instruments. Eugene Wigner in 1960 would go on to write an article ‘The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences’ where he concludes ‘the miracle of the appropriateness of the language of mathematics for the formulation of the laws of physics is a wonderful gift which we neither understand nor deserve’.

Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica is one of the most important books on mathematics ever written and had a particular influence on astrophysics.

Sir Isaac Newton, the developer of modern mathematical techniques in physics including the Law of Universal Gravitation.

Einstein and Relativity

Albert Einstein’s development of the Special and General Theory of Relativity in 1905 and 1915 led to the Relativity Revolution and the idea that time and space are intertwined as a single object, a phenomenon called by the mathematician Hermann Minkowski ‘spacetime’. This four-dimensional object had three dimensions we call space and one dimension we call time, but integrated together so that every observer in the universe sees them as a single mathematical object. Among the central discoveries of relativity is that matter and energy are equivalent ways of describing the same things, and this is codified in Einstein’s iconic equation E=mc2. This simple idea allowed astronomers to eventually discover that stars obtain their luminous energy through the fusion of hydrogen nuclei, which causes millions of tons of matter in a star to be transformed into pure energy every second.

Einstein’s general relativity also offered the first mathematical treatment of the origin and evolution of the universe, which later predicted the expansion of the universe discovered by Edwin Hubble as the Hubble Law, which is stated as V = Hd. Also, Einstein’s relativistic version of gravity led to the prediction of the existence of black holes in which matter is hidden from view by a region of space called the event horizon that extends a distance of R = 2.89 M kilometres from an object with a mass of M times the mass of our sun.

Theories based on Observation

In addition to the various mathematical theories of space and time provided by relativity, physicists had been developing in parallel detailed, observation-based theories of the nature of matter and energy beginning with James Clerk Maxwell’s Theory of Electrodynamics in the 1800s, and leading to the advent of quantum mechanics in the 1920s. It was now possible to understand the nature of matter and its interaction with light in enough detail to account for the spectroscopic data acquired by astronomers in their studies of stars and galaxies. This symbiotic relationship between astronomy and physics, astrophysics, has now led to detailed mathematical models of the evolution of stars, the formation of dense objects such as neutron stars and black holes, and a whole host of other astronomical phenomena. In fact, no matter where modern physics goes in its detailed analysis of the forces and elementary particles of nature called the Standard Model, there is always an astronomical system that benefits from the new knowledge. For example, one of the most complex areas of research is called quantum field theory in which the unification of the forces of nature including gravity is being pursued. However, the lessons being learned from this highly mathematical subject are shining a powerful light onto the most sublime question in all of astronomy: ‘How did the universe, itself, come into existence?’

What the combination of quantitative mathematical theories and lightning-fast calculation using computers has allowed us to do is to experience many natural phenomena by greatly slowing down their speeds for atomic systems, or speeding them up for astronomical systems. The accuracy of modern explanations for how things work now rests on making accurate calculations directed by powerful mathematically-stated theories without having to make any approximations, then using supercomputers to render the theoretical prediction into quantities that can be measured. We can test the accuracy of Big Bang cosmology with dark matter and dark energy added, by using our theories to describe how Standard Model matter will interact, and follow the evolution of structure in the universe over cosmological times. The prediction of what the current structure should be like in all of its galactic detail can be compared with what astronomers actually see across the universe today to test the underlying theories. When major ‘new physics’ has been left out, the result is usually a big difference between what the astronomer sees in their data and what the mathematical model predicts. Similarly, the detonation of a supernova and the formation of neutron stars and black holes can be modelled theoretically. The supercomputer calculations then let astronomers slow down the evolution of this process, which takes a few hours so that it can be explored from millisecond to millisecond.

Result of a supercomputer Millennium Simulation of cosmic structure at a scale of 100 million light years across. Each dot represents an individual galaxy, and the model is based upon Newton’s law of gravity operating between galaxies on the cosmological scale.

Modern Astrophysics

Astrophysics in the 21st century has now evolved dramatically from even its mid-1900s roots, while at the same time confronted by challenges that could not have been pursued by anything less than the technology and techniques that have been amassed since the turn of the millennium. Modern astronomers are still intimately involved in the development and articulation of physical theories of specific objects and the universe at large, but now theories may be tested against data with a level of detail that forces theories to accurately predict physical outcomes at higher and higher resolution. Studies of supernova detonations and black hole mergers could at one time be advanced by simple ‘back of the envelope’ calculations performed on table-top computers. Today, supercomputers reveal near-photographic changes in these systems at time scales of milliseconds.

Thanks to the synthesis of mathematics, supercomputer modelling and advanced imaging technology, astrophysics in the 21st century is a far richer and more exciting undertaking than any previous generations of astronomers could ever have imagined. At the end of the day, there are always more mysteries to contemplate, with the prospect of uncovering signs of an even more sublime and inventive universe in the decades to come.

Simulation of colliding neutron stars spanning 27 milliseconds. Each neutron star has about the same mass as our sun but with a diameter of only 50 kilometres (31 miles). Einstein’s theory of general relativity must be used to accurately describe the motions due to the enormous strength of gravity on these scales.

Key Points

• Because data is in the form of numbers, mathematics is the only natural language for data analysis that helps astronomers extract patterns and consistent natural laws from an onslaught of numerical information.

• Many different forms of mathematics are used, with statistics being crucial for understanding the measurement process and discerning correlations in the measurement.

• Our detailed understanding of the universe comes about because with mathematics we can investigate and propose higher-order relationships among the correlations we find in the data. These become entire schemes of understanding such as quantum mechanics, electrodynamics, relativity and cosmology.

• Computers have evolved over the last 50 years into mathematical tools for analysing huge amounts of data and converting mathematical models into concrete predictions of what to look for next.

• Supercomputers are now so powerful that they can follow billions of points of matter in the expanding universe to study the evolution of structure and galaxies spanning billions of years.