The audition for Mrs. Doubtfire felt serious when they issued plane tickets. I was fourteen years old when Mom and I flew to San Francisco with a bunch of other kids and their chaperones for a screen test. There were a few kids for each of the three children’s roles, and they kept mixing and matching, coming up with new combinations of us, like we were toppings at a frozen yogurt bar. Each new group would go into the studio and try to stay cool while we read with Robin Williams and then wait while the next trio of kids went to have their turn in front of the cameras.

Matt Lawrence, Mara Wilson, and I were grouped together early and instantly connected. We adored each other and I jumped at the chance to have siblings, if only for an afternoon. When we were on the mock-set with Robin and then with Sally Field, we went into professional mode, listening attentively to direction and trying to impress the veteran actors with the fact that we were all “off-book” and had our lines memorized. Robin and Sally proved what I was starting to believe about real movie stars: they are lovely. Legitimate stars have no need to pull rank and shoot others down. They are sensitive and collaborative artists who also mean business. They are as serious about getting the shot and landing the joke as the most hard-assed Fortune 500 CEO. Real stars are stars because they are good at both the creative and the business sides of the job.

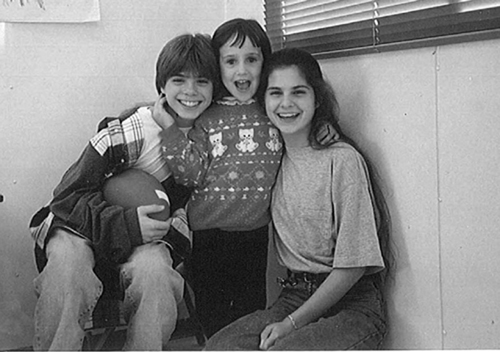

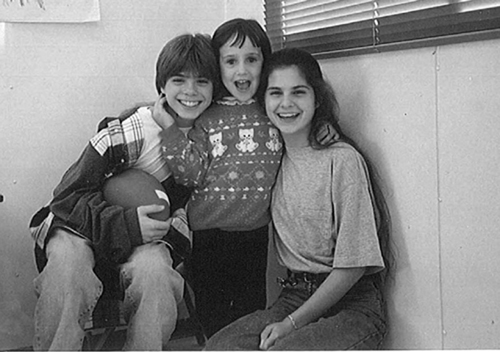

While the other kids were screen testing, Matt, Mara, and I laughed and joked around and confided that we all really wanted to book this one.

“You’ve seen Mork and Mindy, right?” Matt asked me.

I confessed my obsession with Nick at Night reruns.

“But have you seen Robin’s stand up? It’s really funny. But like, dirty funny.”

I thought Robin’s only gig was playing an alien, so Matt was clearly more versed on the career of our potential colleague.

I didn’t much care about anyone else’s resume, I just held Mara’s tiny hand a little tighter and decided that she was mine to take care of. I already loved her.

When the screen test was over, we all loaded up in a bus full of child actors and their parents and went back to the airport. A somber, emotionally exhausted silence fell over the group. It’s always hard to tell how these things go. You can feel like you totally nailed it, but politics or skin coloring or someone else who just nailed it a little more can leave you unemployed after even the greatest audition. All of us had done our best and now it was just up to the producers to figure out which pre-pubes-cent amalgamation would play the children of Robin and Sally.

Matthew Lawrence, Mara Wilson and me, in the school trailer of Mrs. Doubtfire.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.

As we reached the airport I saw a rainbow shimmering through the misty San Francisco sky. It was clearly a sign that I booked the gig. I guess my competitors could have seen the rainbow, too, but for whatever reason, I was convinced that none of them did. That rainbow was mine, and the job would be, too.

I went home to Canada and managed to attend almost ten whole days of 9th grade before I left to film Mrs. Doubtfire for several months. With my head hung low, I went to my teachers and told them the situation, apologizing that they would have to put together work for me to do while I was away. Some teachers put up a minor fuss, others were downright obstinate. I vaguely remember one saying something supportive, but generally it was the same old battle.

We arrived in San Francisco and Mom and I settled into our new home at the St. Frances Hotel. It was a historic hotel from the early 1900s, that was complete with gold-capped columns and a fancy art collection in the lobby. We dragged in our overused luggage, introduced ourselves to the staff, and settled in for four months of tiny soaps and prompt turn- down service.

On one of the first days of rehearsals, while we were still trying to find our way around from the school trailer to the craft services table, the director, Chris Columbus, introduced us to his mother. She had stopped by to visit the set and she joined Matt, Mara, and me for lunch. She was a sweet older woman, a bit eccentric, but nice all the same. The three of us felt like we had to impress the mother of our new boss and made as much small talk as we could manage at fourteen, thirteen, and five years old. After lunch, we shook her hand and attempted to say professional-sounding things:

“So nice to meet you,” I said.

“Hope you enjoy your stay in San Francisco,” said Matt.

“Bye!” said Mara.

We went back to the schoolroom to try to get a little educated before rehearsals resumed, and it was only when we returned to set that we found out that we had just had lunch with Mrs. Euphegenia Doubtfire. We had completely fallen for it—hook, line, and latex bosoms. Until that moment, the whole Robin-as-a-woman thing had seemed pretty farfetched and had the potential to be an embarrassing career misstep for everyone. We all wondered if we were just doing a bad Tootsie rip-off. But maybe this drag thing could be believable, after all.

Even close up, Robin’s makeup was phenomenal. It was the expert work of Greg Cannom, Ve Neill, and Yolanda Toussieng, who would rightfully win an Oscar for their effort. I was impressed with the fact that when Robin (a notoriously hairy man) was in character as Mrs. Doubtfire, they went so far as to shave his knuckles and the backs of his hands. He once caught me staring at the stubble that grew by the minute on his fingers and called me out on it. I had never been good at being teased but I never knew how comprehensive the mortification could be until a professional teaser mocked me.

The biggest challenge was learning how to deal with Robin’s improv on set. Ad libbing has never been my strong suit and I soon realized that I could not just look to the director with a panicked, wide-eyed expression every time Robin went off-script. Also ineffective was my attempt to just blurt out my line whenever Robin stopped for a breath, regardless of if it was logical or not. Eventually, I learned to ride that wave with him. I would never become a brilliant improv actor, but there were some good lessons in there about being flexible and embracing the moment. Learning to really listen and respond rather than just waiting for my turn to talk was a valuable skill, on set and off.

The whole experience was a blast and there were times I noticed myself, in the midst of this unusual situation, enjoying regular kid things. Matt brought his dog along to San Francisco and we would play fetch with Jack in the fancy ballroom of the beautiful and historic St. Frances. I’m not sure that the staff really appreciated a golden retriever bouncing off the mirrored walls but apparently no one is inclined to protest when a production company reserves entire floors of rooms for months at a time. Mara and I ordered butterfly chrysalides through the mail and kept them protected in a mesh tent until they were ready to be released. We opened the enclosure and squealed as our monarchs took flight and zigzagged through the trees in Union Square Park. Matt and Mara felt like the siblings I always wanted, and Robin and Sally could not have been more wonderful to us. Sally brought us games and books and smothered us with hugs every morning. Robin sang, “Lydia the Tattooed Lady,” whenever I walked on set. The workdays were long, but no one complained because we knew they were always longer for Robin, who endured hours in the makeup chair.

Although we felt loved, I don’t remember anyone treating us like we were particularly special. We were not put on any type of pedestal at work; people were not constantly telling us how wonderful we were. It was more like we were part of a large extended family and although people were looking out for us, I never felt a sense of being worshipped. We were there to do a job and although we were not expected to be perfect, we were expected to be prepared for work and do our jobs well. We always knew we’d have another take or could ask for an extra moment before an emotional scene if we needed it. When anyone flubbed a line, whether it was Mara or Pierce Brosnan, we all laughed it off and just went back to one to go again. The work was hard, certainly, but we felt supported. There was also a sense that being part of this production had the potential of changing much in our lives. People seemed to be trying to prepare us and keep us grounded because of attention that might come our way after the film was released.

By the time I was fourteen, I had been on catty sets, with weird, internal competition for screen time and the attention of the director. Older actresses who were losing the battle with time struggled with their age and took it out on me. There had been vicious attacks about trailer size and contractual perks. I had been on shows where kids were an unwelcomed addition, and our cuteness couldn’t compensate for the underlying distain. I had been treated like an adult more than was necessary, being the object of inappropriate affections from producers who left gifts of cashmere sweaters in my dressing room and hugged me for too long. Those men told me how beautiful I was, and how I was so mature for my age, and they just couldn’t talk to their wives the way they could talk to me. Even though I was dying to be grown up like everyone else I was working with, I was not ready for certain types of reality that tended to show up on set. On Doubtfire we worked with people who respected us, yet understood we were still children. It was good to know that there were ways to do it right.

Film sets are large operations, with lots of trucks and trailers and other inconspicuous places for over-zealous fans to hide. Mrs. Doubtfire was a high profile shoot, so we needed security. Big, scary-looking security. Preferably with unkempt beards and an affinity for leather.

Like the other cast members, I was assigned someone to look out for my personal safety on set; his name was Fuzzy and he was a Hell’s Angel. I didn’t really know what that meant, but Fuzzy was a massive and kind-hearted man and I was incredibly fond of him. His job was pretty straightforward: walk all eighty pounds of me from my trailer to set and look terrifying. There were mobs of people behind police barricades; some brought coolers, prepared to spend hours, if not days, desperately trying to get a look at anyone who was working that day. Some actors find that kind of thing to be exhilarating: the clawing, screaming and crying at the mere sight of them. It’s validating and encouraging, proof that their work matters to someone. To me, it was scary and simmering with unintended yet potential violence. I felt like a gazelle in front of a pride of lions who had brought their own video cameras and lawn chairs. When it was time to go to set, Fuzzy would pound on my trailer door, the assistant director standing next to him looking tiny. She adjusted her headset and looked up from her clipboard.

“Hey, Lisa. They’re ready for you on set.”

“You ready to go, kiddo?” Fuzzy would growl.

The teeming mass of fans was positioned just around the corner, amped and waiting. There would be a moment of wondering if it was feasible to just hide out in my minuscule trailer bathroom. Sure, your knees hit the wall as you sat and it smelled like an outhouse, but all that might be preferable to navigating that crowd. But just beyond the throng was set, comfortable, easy set, with the crew and my fake family.

As soon as I stepped outside, the group of people went crazy. This was not because they had any clue who I was, because there was no reason for them to know me at all. It was just that if a trailer door opened and someone emerged, screaming ensued, regardless of who they were. Seeing a person who was simply affiliated with the movie seemed to be sufficient for absolute mayhem.

When I heard the roar, my heart raced and my face burned with anxiety. Then I looked to my right and up, way up, and remembered that I was with Fuzzy. I was invincible. Or maybe it was more like I was invisible—because as we passed the crowd, he kept me on his far side, away from the mob and I could walk next to the hulking bear of a man and literally not be seen.

If anyone even came close to me, I imagined I would find myself swept high into the air. Fuzzy would hold me above his head with one hand like I was a waiter’s tray, as he kicked aside whoever posed the slightest threat to my well-being. Then, he would run me off into the sunset, far from the maniacal movie fans, our long ponytails flapping simultaneously in the wind. We never had to test this, as no one was moronic enough to mess with Fuzzy. He was always kind and would slow his pace so my short legs could keep up. In that moment, I was safe. I was cared for. I knew that was really all I needed.

The lengthy shoot for Mrs. Doubtfire was the last straw for my high school; a few months into filming they requested I simply didn’t come back. They were frustrated by my frequent absences and felt that I was not giving my education the proper attention. This relationship just wasn’t working, they said, my coming and going was a disruption to the classroom and created too much extra work for the teachers. It was my first break-up. They didn’t even have the decency to try the whole, “it’s not you, it’s me,” excuse. It was definitely me. At age fourteen, they decided to end my education.

It was devastating. While school had never been enjoyable, it seemed a necessary evil that needed to be survived in order to be a proper human being. What would I do now? I tried to just go to work and forget that I had been thrown out of school like some delinquent, but I was clearly distracted. When Robin noticed my sadness and asked what was going on, I explained the whole situation. He promptly asked for the principal’s address and wrote an incredibly kind note. He spoke about me in embarrassingly glowing terms. He explained that I was attempting to get my education while pursuing my talent and the school should encourage and facilitate that. He respectfully asked for them to reconsider and help me in balancing my life.

It didn’t work. Months went by and the school didn’t acknowledge the letter and didn’t change their mind. I was defeated and humiliated. My weird life had officially become too bizarre to be occasionally piggybacked into normal circumstances. Later, someone told my dad that the letter with Robin’s signature was framed and hung in the principal’s office. I wondered if anyone noticed that the letter was essentially a bitch-slap to the entire institution, or if they were blinded by the fact that it was on Mrs. Doubtfire letterhead. Sometimes fame can have unintended consequences. But at least I knew that in an industry notorious for back-stabbing, Robin was a generous soul who had been willing to stand up for me. My gratitude for that is eternal.

When I went back to Canada after Mrs. Doubtfire wrapped, life was completely un-tethered. School had always been a challenge, but had also had a grounding effect. It was the one thing in my life that appeared to be standard and regulated. My parents worried about my social interactions, and rightfully so. Being an only child and an actor whose friends tended to be twice my age and/or in biker gangs, they were justifiably concerned.

In an attempt to keep me from becoming completely feral, my former high school granted me permission to participate in what might just be the most intense hour of high school interactions: lunchtime. My dad would drop me off in front of the school that had rejected me, so that I could eat in the cafeteria. By that time, I had gotten to know this one girl, Kathy, and she had introduced me to her group of friends.

The moment of walking into the cafeteria was always ulcer-inducing. If Kathy was busy with her last class or I arrived early, there was nothing to do but loiter uncomfortably in the cafeteria doorway and wait for her to show up. There was no way I could cross the threshold without Kathy acting as my membership card. I’d scan the room, searching for her blond hair. The cafeteria was always too bright and smelled like Clorox and old apples. Groups of kids huddled together in tight packs, sharing meaningful glances and bags of chips. They all knew the rules of engagement. All I knew was that in movies the freaky kid always got tripped in the cafeteria. The murmuring seemed to get louder as I scanned the clusters of adorable headbands and backwards baseball caps belonging to kids who all seemed to know their place in the system.

Finally, when Kathy found me pretending to read the class president nominee propaganda for the fortieth time, she would grab my arm and walk me to her table of friends, who would nod their acknowledgement and shuffle around backpacks so we could join them. I unpacked my peanut butter sandwich and a grape drink box and nodded along with her friends, pretending to know what the hell they were talking about when they complained about that social studies assignment and the new substitute teacher for French.

I played the part of “student” quite well, and some kids seemed to believe that I attended school there but we just didn’t have classes together. Their mistaken assumption felt like a rave review in the Hollywood Reporter, but it was still disconcerting that even in what was supposed to be my real life, I was playing a role. I pretended to know my way around the large school, acting as if I intended to end up in the dead-end hallway under the stairs.

I pretended to fit in with the other kids, smiling like I knew who the Spin Doctors were even though I didn’t because I had been on location and hadn’t had time for teenager things like that. I didn’t know which stuff to laugh at, not to mention the type of laugh that was called for. Did that comment about the “straight-edge kids” deserve a total crack up, or was a slight chortle with an eye roll more appropriate? Or had I completely misunderstood and it wasn’t funny at all and a respectful nod would be best? I spent my whole work life studying people’s facial expressions and I did the same here, mimicking their reactions within a fraction of a second so that I could blend in.

After we ate, we spent the rest of the lunch period sprawled out in the hallway, throwing things at each other and commenting on the fashions of the kids who walked by.

“I’ve got my ape class in the Ken lab this afternoon—which totally sucks,” they’d lament.

“God, that’s the worst,” I’d commiserate.

I had no idea what they were talking about. I was too embarrassed to ask anyone, and it took me years to figure out they were talking about AP classes in the chem lab. Their short-hand reminded me of set lingo, except I was never that confused on set. Terms like Abby Singer and four-bangers and apple boxes were the foreign language that I’d learned along with English when I was growing up. It was such a luxury to understand everything that was going on, where to stand, what to say, and when to laugh. In that high school hallway, I’d think wistfully about the smell of lighting gels and the comforting weight of hitting a sandbag with your toes when you got to your mark. I missed being wrapped in the familiar routine that these high school kids seemed to feel here sitting on the scuffed, gum-stained linoleum. So, I just sat quietly with my back against a bay of lockers and imagined that my own locker was just down there on the left.

When the bell rang and students shuffled off to class, I pretended to walk to my imaginary locker and instead I snuck outside to wait for my dad to pick me up. Standing outside, the eerie stillness of a high school in session settled in around me. The chain clanked against the flagpole as I stood just behind the corner of the building so that no one could see me from the classroom windows. Within those windows, my peers were sitting in tidy rows and looking bored. I was desperate to be part of that, but it just didn’t seem to be my path. Nope. My path was unusual and painful and involved packing a lunch for a school I was forbidden to attend. All the autographs I was starting to sign and the letters from Robin Williams couldn’t make up for the fact that I didn’t have a locker and I didn’t know who the new French teacher was.

Even though there were challenges, being in Canada had its perks. I loved canoeing on the river near my house in the summer and skating on it in the winter. It was refreshing to have a break from the constant industry chatter about movies. While my trips “home” were starting to be fewer and farther between, there was still a great sense of peace there. Although my accent would never again let on, I would always be Canadian.

On one of my trips up north, we got a dog. Mikki had passed away several years earlier, and although we still mourned the loss of our ill-behaved canine, we felt it was time to open our hearts to someone new.

Our Australian Shepherd mix was the most passive animal on the planet and we didn’t see her walk for a month; as soon as she saw us, she would throw herself on her back as a show of appreciation for inviting her into our family. My little ball of gratitude needed a name. The dog was as beautiful as….as….. Marilyn Monroe. (I was still obsessing about old movies and scoffed at those who thought classic films meant The Graduate.) But Marilyn was a terrible name for a dog and way too on-the-nose to be cool. So I decided to be all “insider Hollywood” about it and name her Marilyn’s real name. I began calling my pup Billie Jean. It suited her and the story made me sound cool and in the loop.

It only took a few weeks for someone to astutely point out that Marilyn Monroe’s real name was, in fact, Norma Jean. But by then Billie Jean had learned her name and Norma was also a terrible dog name. So, my dog was named after Marilyn Monroe, but in my attempt to be all Hollywood insider and cool, I had failed miserably and inadvertently paid tribute to a tennis player.

Billie Jean started traveling with me on film shoots and spent much of her puppyhood in Star Wagon trailers. She chewed on exposed wires under the driver’s seat and covered my wardrobe in dog fur. She stayed in a fancy hotel and occasionally peed under the grand piano in the lobby. She stayed in hotels in rough neighborhoods, too, carefully lifting each paw to step over the discarded Listerine bottles that kids had attempted to get drunk on.

I became one of those actresses that traveled with her dog and while it was a stereotype, it was about much more than that. Walking Billie Jean after a long day at work centered me and brought me back to myself. Her love was unyielding, whether we were on set or in our backyard. She was my constant and loyal companion who reminded me that to some, none of this film stuff mattered in the slightest, as long as I could still throw a Frisbee.