After all those years of corporate apartments and murderous mansions, it was time to find a more permanent place to lay my head in Los Angeles. Age fifteen seemed a good time to get into the real estate game. The house my mom found was close to my favorite bagel place and had a gorgeous grapefruit tree in the backyard. So, I bought a tree, which just happened to come with a house.

It was the summer of 1994. The Northridge earthquake had hit in January and the city was still reeling. Rubble remained strewn about, as people tried put their lives back together while waiting for the insurance checks to clear. We had been in Canada for Christmas and missed the seismic event but my mother, always the opportunist, saw something positive amongst all the cracked drywall and crumbling roofs.

It was a simple one level ranch-style house with two bedrooms. It had been built in the 1930s and had all the charm and architecture of the era. It also had all of the crappy plumbing and electrical wiring of the era. It was a weird little place. The shower door was decorated with a frosted glass deer, eating frosted glass flowers in a frosted glass field. There had been clumsy and certainly illegal additions, meaning that there were random brick walls or windows that peered into adjacent rooms. Surprised guests would open a door, expecting a coat closet, and find themselves in a completely tiled room that served as a shower or a handy place to commit an easy-clean-up slaughter. Modern conveniences, such as temperature control, functional kitchen appliances, or windows that closed all the way were not part of the house’s repertoire.

I lacked the motivation to fix those sorts of things, and without stable money coming in, those kinds of luxurious extras didn’t seem financially feasible. The money in the bank was what I’d have until the next job, and if there was no next job, it needed to last until my actor’s union pension kicked in. My actor friends always complained about their lack of funds, so, I tended to be in a constant state of panic that I was broke. Even though I was still a teenager, I was convinced that each paycheck might be the last one I would ever get.

The house had seen better days. Before me, it had been mostly inhabited, it seemed, by feral cats. The floor buckled in some places, pushing up cheap parquet tiles into jagged, threatening peaks. The ceiling was collapsing in other places, raining down insulation and rat droppings onto horrified Sunday Open House visitors. The house had a long line of short-term tenants in its past, who had no concern for sustaining its health. The earthquake appeared to be the final straw, the last owners had abandoned it and the bank became its reluctant owner. The house needed saving. It was awkward and strange and I absolutely loved it. We had a kinship. Mom and I did just enough renovation to make it livable, moved in, and made it our California home.

My next door neighbor, Paula, was an elderly German woman who loved to garden. She was short and sturdy and always moved quickly with intense determination, as if something behind her had just recently blown up. Because the house had been abandoned for such a long time, she had decided that she was responsible for it. When I first moved in, Paula kept telling me how happy she was that I was going to be living in her house. With her garden. She wasn’t the type of woman that you could correct without getting something cracked against your knuckles, so I just said that I loved her house and was happy to be there. My meekness only seemed to encourage her, as she developed a habit of walking in my front door and demanding that everyone present identify themselves.

Paula’s most helpful form of intrusion was caring for all the rose bushes that she had planted on my property. Since I couldn’t keep a cactus alive, I was happy to have her wander around my yard, early in the morning, caring for the plants. She would get excessively emotional about gardening; she’d enthusiastically praise the rosebushes for their growth or yell impassioned threats towards the aphids that were chewing on them. This habit of hers, while undoubtedly beneficial to the flora, would become problematic later on. My Jewish boyfriend found Paula to be quite unnerving; he claimed that he had a genetically ingrained fear of anyone waking him up by shouting in German.

“The hill” separates the porn stars (San Fernando Valley) from the movie stars (Beverly Hills). My house was right on that hill, just on the sketchier side. The valley was populated with establishments where you could pawn something and then conveniently get some fro yo right next door. Delis, nail salons, and unsavory video stores were all slung together in long, low strip malls with flat roofs and large parking lots. Palm trees striped the streets, occasionally obscuring the billboards advertising liquor or TV movies. The smog settled in a thick layer between the mountains, giving the valley a golden radiance that you could easily delude yourself into thinking was merely a California glow.

My house was on Coldwater Canyon, essentially a two-lane freeway that snaked over the hill and delivered people from the Valley into the heart and soul (if it had one) of Rodeo Drive shopping and cosmetic dentistry offices. Most of the time the traffic was horrendous and people would sit in their cars, waiting to drive five miles per hour and sucking on fumes, because their convertibles were open so they could get both lung and skin cancer simultaneously. For three hours every morning and evening, a slow, New Orleans-style funeral procession of BMWs and Mercedes crept past, twenty feet from my front door. My bedroom was at the front of the house and inhaling those fumes for so long is why I don’t understand geometry. I consoled myself with the fact that all those cars spewing noxious vapors in front of my house did the same thing in front of the multimillion dollar 90210 houses, just a couple miles and forty-five minutes later. If the acting work dried up, I planned to pay the mortgage by selling grapefruit to the commuters who were stopped in front of my driveway and hopefully in need of a low-carb breakfast.

I never felt shame in my love of the Valley. Sure, it is the porn capital of the world and is always ten degrees hotter than the rest of L.A. Sure, Valley Girls are known worldwide for being annoying and gagging on spoons sideways. But the place has the best vibe. It always felt like a true neighborhood to me. At my favorite hangouts, they knew my name and I would eventually date half of the wait staff. I was friendly with my neighbors and knew what they did for a living, or more accurately, which aspect of the film industry they worked in. I could walk to places, something nearly taboo in L.A. where the rationale is that if you can’t use it as an opportunity to show off your car, there is no reason to go out.

I found myself in a dangerous situation: I was a teenager with a house and no personal boundaries. Everyone wants to come to L.A.; they have dreams of being an actor, a director, a screenwriter. They just wanted to be somebody and L.A. claimed it was the only place where that is possible. I said yes to everyone who might have asked and before I knew it there were fourteen of us living in my two-bedroom house, including Mom and I. Since I was so used to growing up in a constant state of disarray of home renovations, when I was setting up my own home at age fifteen, it made sense to continue the trend of chaos by turning it into as a refugee camp for creative types.

My very first boyfriend was the first to move in. He was eighteen years old and we met in Denver where he had been hired as my personal assistant on a project. He had driven me around, brought me endless cups of English Breakfast tea, and graciously put me out of my only-been-kissed-on-film misery. He was an aspiring actor/director and my mom allowed him to move in under the stipulation that he slept on the other side of the house and was never out of her sight. There was also an artist and her girlfriend. Various actors from Canada and their mothers/wives/mistresses/children cycled through. There were two backpacking Australians, and I honestly have no idea how they ended up joining us. You never knew when friends of someone who had sat next to my boyfriend at the movies might show up at the door, suitcase in hand. My mom operated under the assumption that we should help people out if we could, so everyone was welcomed in.

There was also an assortment of animals in residence. In addition to Billie Jean, we had gotten another dog, an eleven pound Italian Greyhound named Cleo, who had spindly legs and an impertinent manner. There was a stray terrier who we found running on the freeway who only understood Spanish and had an insatiable appetite for windowsills. Baby birds who had fallen out of nests were kept warm under towels and desk lamps in the bathtub until they were rehabilitated enough to be placed in the branches of the grapefruit tree. There were seven feral newborn kittens that had been birthed in the insulation within the wall of the dining room and then abandoned by their mother. After hearing pitiful mewing for days, we took a hammer to the drywall and rescued them. No one could be bothered to patch the hole, so we solved the problem by hanging a picture over it.

Everyone simply negotiated his or her own personal space. The couch and oversized chair were on nightly rotation, the Australians slept under the dining room table and the garage housed those who overflowed from the house. Did anyone pay rent, contribute to utilities or the thousands of dollars in phone bills every month? Of course not. Creatives don’t sully themselves with such tedious logistics.

Did I complain? Of course not. I was an only child who always wanted to be part of a big family. I was a full and willing participant in this situation. If my parents thought it was strange, they never stepped in, and I would have likely resented it if they had. I opened the front door wide and welcomed in every stray dog/cat/artiste that wandered past.

We didn’t have enough keys to the house and most of my roommates were not the types of people who could rein in their inspired impulses enough to do something as mundane as keep track of a set of house keys, so we just left the door unlocked all the time. The house was populated enough with people coming and going at random hours that it would be impossible to burgle the place. A robber would have tripped over an interpretive dancer or a Canadian before they could get to anything worth stealing.

No one in the house had a real job, so there was lots of time to just hang out. A few people were musically inclined so they would write songs called, “The Coldwater Blues,” on the old upright piano I had picked up at a garage sale in Beverly Hills for $25. I would attempt to sing with them, but since my one audition for a musical had not been encouraging, I usually just clapped along. (I auditioned for the part of Cosette in Les Mis under the pretense that they were “not looking for a singer.” The audition feedback was that while it was true that they were not looking for a singer, they were looking for “more of a singer” than me.)

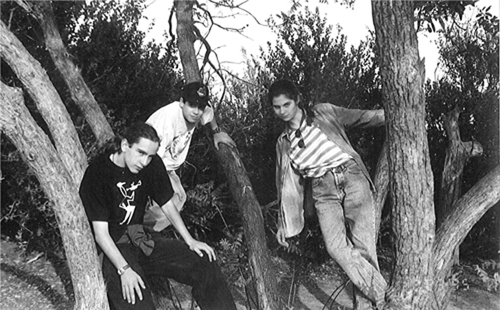

The roommates and I would spend hours in the woods staging photo shoots, thinking we looked subversive and misunderstood. We would strike poses that embodied our dark, esoteric natures. We would crouch at the base of the tree and examine a leaf with thoughtful, arty expressions on our faces. I waved away the smoke from my friends’ hand-rolled cigarettes while we sat in 24-hour coffee shops and debated important, existential matters and read obscure plays. They claimed the title of “artist” with such fervor that I wanted it, too. No one balked when I used it on myself, so it seemed I could justifiably claim membership to that group. I filled spiral notebooks with bad verse and tried to channel the Beat poets.

It was nice to be considered an artist, but it felt more like I was doing a job that was second nature and that I had no memory of not doing. In fact, my job had been recently feeling more like the work of a ventriloquist dummy than someone with artistic talent. I was someone who said what she was supposed to, while standing in the specific place she was told to, while wearing the chosen clothes and hair styles. Some days I felt I’d go limp when there was no one pulling the strings, falling to the floor in a pile of rote dialogue and contrived emotions. But the label of artist sounded nicer than puppet, and allowed me entrance into this group of charmingly tortured souls. So, we collectively shivered in horror at the thought of normal jobs with predictable schedules. We pledged allegiance to the craft and swore we’d never be anything but artists. L.A. was where it was at and we’d rather starve than leave the nesting ground for all that was inspired and worthy.

When creative people get bored, it results in photoshoots.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR.

If we weren’t skulking around a coffee shop, we were at the movies, critiquing other actors. Actors always think they can play a role. Even if it’s a part that is thirty years older and of a different gender. Those are the roles that get nominations and so every single job felt like it was snatched out from under us. We’d elbow each other in dark theaters, pointing at the screen and loudly whispering, “I auditioned for that.” We’d engage in long-winded, post-film dissections of why we would have been better in the role. When normal people get passed over for a job, they don’t have to watch the person who beat them actually performing the tasks. It’s harder to recover from the rejection when you have the opportunity to assess your competition’s final contribution. All you can think about is how you would have punched up that line or held that meaningful glance a moment longer or totally would have rocked the role of Rogue in X-Men (or whatever). The failure lingers and gets very specific. We spent the majority of our time judging others while we waited for something exciting to happen to us.

When it did, that’s when the real trouble began.

There is a limited amount of cheerleading available within the creative soul. There’s a certain stage where that support is replaced with some serious envy-fueled mockery. It’s grueling to be an artist; struggle is a prerequisite and in general, you are considered to be a society-draining slacker. It’s painful to see someone down the hall doing well when you are not. The ensuing reaction is not intended to be malicious; it’s just human nature.

I had an audition for the film On the Road, directed by Francis Ford Coppolla. I had made it past the casting director and was going to a call back to read for Mr. Coppolla. It was a major honor, and I was thrilled. This guy was serious; after all, he had almost killed Martin Sheen during Apocalypse Now.

When news of my meeting with the film legend spread through the house, it activated the simmering energy of our cast of struggling characters. I’ve heard that crabs will pull each other down when one tries to escape a pot, relegating the whole group to an inevitable demise. I’m not sure what that crab instinct is, but they might have learned it from a group of actors crammed into a two-bedroom house. The crab claws came out.

“Did you hear about Lisa’s audition? She’s reading with Francis Ford Coppola. I bet that guy just thinks he’s the shit.”

“God, I’m sure he’s a total fucker.”

“Ha! Yeah, what a fucker. Francis Ford Fucker.”

So, he became Francis Ford Fucker. That was how he was referred to in my house. For weeks.

“Big fucking deal,” they said, “Go read with Francis Ford Fucker. You should say that to his face, just to see what he says. Say, ‘Hey there, Mr. Francis Ford Fucker.’

I did read with Mr. Fucker. It went fine. He seemed like a nice man, fairly quiet and reserved, although the whole audition was drowned out by my own thoughts. All I could hear when I walked into the room was the taunting of my freeloading housemates and my silent refrain of, “Don’t say Fucker, don’t say Fucker, don’t say Fucker.”

(I didn’t call him Fucker, not that it mattered, as I didn’t get the part anyway. The film got shelved and finally made it to production a few years ago. Kristen Stewart, who would have been about five years old at the time of my Fucker audition, played the part I read for.)

That one single audition seemed to ignite the prickly tensions at my house and people started to pick fights with one another. If an actor is not satisfied with his or her career accomplishments, at least they can taunt others in a way that expresses their creativity and passion in its most exquisite and cutting tenor. Our rock and roll photo shoots became rarer as I became the resident guidance counselor/therapist. People started writing me long, emotionally wrought, hand-written letters that they slipped under my bedroom door, complaining about the lack of respect from other housemates and asking me to fix it. I was fifteen and couldn’t fix lunch. But I listened and said, “He didn’t mean it that way,” then made everyone hug it out while I went and paid the phone bill. I bought more bagels and the good cream cheese in the hopes that everyone would settle down and we could go back to our tight little community of misfits, debating the merits of the latest Lasse Hallström film.

Just down the street from the house, there was a vacant parking lot with a fence that faced the road and someone put a Mrs. Doubtfire poster on it, coincidentally right after I bought my place. Every time I went home, I passed that poster and wondered who had put it there. I’d see my face, demurely peeking around Robin’s giant breasts and my real-life face would get hot and embarrassed. I’d run home and make sure the curtains were drawn tight and hope that my roommates had taken a different route. They would tease me about it, for sure. My boyfriend joked that he was going to get the poster tattooed on his ass and my roommates had all laughed and I had rolled my eyes and tried to not let my humiliation show. Why was that poster just out there? For everyone to see? The cast had never even posed for that photo. It wasn’t real, they had just pieced together disparate parts of other publicity shots to make it look good. The rainy season came and that poster ripped and melted into a mealy pile on the asphalt and I could comfortably drive on that road again.

It soon became clear that even the good cream cheese couldn’t soothe the drama that bubbled forth from the small house. People threatened to move out and never did. There were disproportional threats of violence waged when the last bag of microwave popcorn was gone. Phone messages from agents and managers may or may not have been delivered in a timely manner. When I got a job filming out of the country, our group home disintegrated; everyone moved out, going back to wherever “home” was, or to live with other boundaryless friends who must have also been lonely only children.

I packed for the shoot and locked the front door, leaving my weird little home to take a deep breath and enjoy the quiet. Paula kept up her constant vigil, keeping her house company, watering roses, and bullying aphids. All that was left of our commune was the smell of sit-com scripts left out in the rain, cheap cigarettes, and desperation.