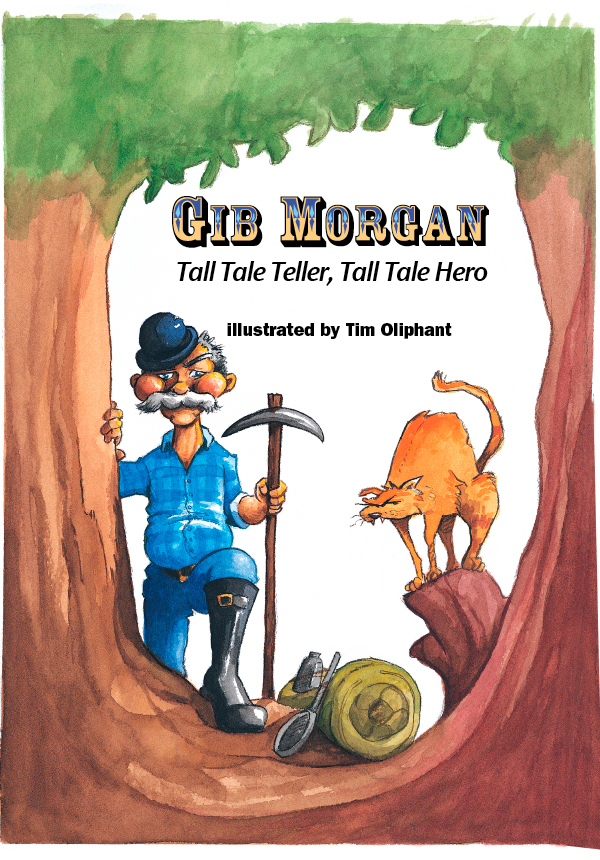

Gib Morgan:

Tall Tale Teller, Tall Tale Hero

Oilmen, from Pennsylvania to West Texas to oil fields around the world, have heard at least a few of the legends of Gilbert “Gib” Morgan. He was a real person, born in 1842 in Callensburg, Pennsylvania, not far from Titusville, where the first oil well was drilled in the United States in 1859. He died in 1909. He was a veteran of the Union Army, and a “boomer” — an oil gypsy who followed new strikes around the country.

A natural-born storyteller, he recounted extravagant tales that starred himself. Folks recalled him as a dark-complexioned old fellow, with a heavy gray mustache, earnest blue eyes, and a sincere-sounding voice that made people half-believe some of the outlandish tales he spun. He wandered the fields of many states, accompanied by his old tomcat, Josiah, who was mean enough to run off any dog he tangled with.

Field crews eagerly awaited Gib’s visits, watching for the figure in high leather boots, jeans, blue flannel shirt, and scruffy black derby perched on the side of his head. When they gathered in the evening to relax, Gib sat in the center of things and recounted his adventures, such as the time he built the biggest rig in the world.

According to Gib, there was a patch of Texas soil that the “rockhounds,” who scouted likely spots for oil wells, felt was oil-rich. However, the best drilling crews couldn’t make a hole to draw the crude out. The ground was too soft, and kept falling into the well. The drillers used a bit, or cutting tool, to make the hole, and then they lowered lengths of pipe to hold up the sides. But each time they lowered another section of pipe, it would have to be narrower than the previous one, so the bits had to keep being smaller as they bored deeper into the earth. Finally, the pipe was so narrow, they could no longer lower the cable and bit (what was called the “string of tools”). At last, the frustrated boss asked for Gib’s help.

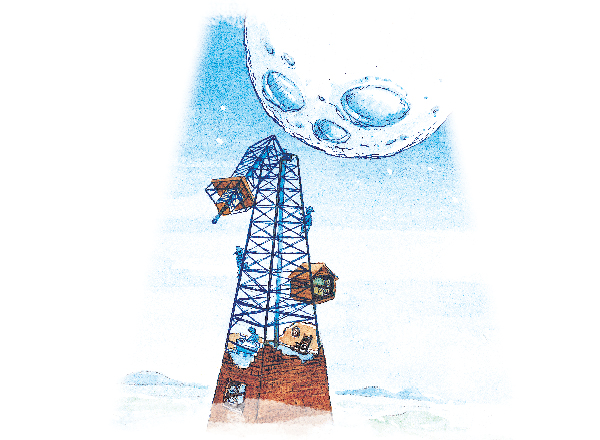

First, Gib ordered special tools — some big, some little. Then he started work on the rig itself. The derrick covered an acre of ground. “I figgered the work was likely to take a long time,” he said, “so I shingled the outside and plastered the inside, hung pictures, and moved in furniture. By the time it was done, the rig was so tall I had to hinge the top part so it could fold over and let the Moon by. Since it took 14 days to climb to the top to work, I built bunkhouses fer the men to sleep in on their way up or down.”

Gib started drilling using his biggest drills, and then he used smaller and smaller bits, as the workers shored up the sides of the hole. By the time he reached the 2,000-foot level, he was using the smallest of his new tools, which slid down one-inch tubing. But then he found that the last part of the hole he’d drilled, when lined with tubing, was too narrow for even his smallest bit.

“That didn’t stop me,” Gib boasted. “I brought in the well with a needle and thread. Soon’s I poked that needle into the oil sand, the gas pressure pushed the oil up the borehole, and ‘black gold’ gushed from the top of the rig. Luckily, I’d put a real sturdy roof on the derrick, or that oil woulda shot a hole in the sky.”

Then he added, “With some of the money I got, I built a hotel 40 stories high with narrow-gauge railroads on each floor to take guests from the elevators to their rooms. Since most folks like south and east exposures, I put that hotel on a turntable, so ever’body got to face those directions at least part of the time.”

One of his favorite stories was about Strickie, the boa constrictor Gib supposedly found on a drilling expedition to South America. Drilling had stopped because Gib had used up 10,000 feet of cable drilling a deep well, and he was waiting for more cable from the United States. The minute he saw the boa, which was about 20 blocks long, Gib got an idea. He had his men haul the snake back to the rig, where he used him as replacement cable. This was the start of their friendship. Gib kept the snake well fed and well cared for. A grateful Strickie slept in front of Gib’s bunkhouse door, guarding him at night. If Strickie’s length wasn’t quite enough, the snake would obligingly shed his skin, thus doubling the length of cable, and letting the men finish a well.

Though he was a man of average height and weight, Gib claimed to have done many things that were on a giant scale. Once, he said, he used a spool of drilling cable for a line, a steamboat anchor for a hook, and a steer for bait, to catch a catfish so big that the water level in the river dropped two feet when he reeled it in. He boasted that he had a horse named Torpedo that was 22 yards long. “Never turned him around,” Gib said. “Just threw him into reverse.”

One of his greatest achievements, he said, was building what was then the biggest pipeline in the country. It ran from Philadelphia to New York. When asked if he made money on the pipeline, Gib would sigh and say, “Lost ever’ cent. I invested in the polka-dot business, and made a barrel of money. Then a feller invented the square polka dot. Pretty soon ever’one wanted those new-fangled dots, and I went bust.”

For generations of oil workers, the stories of Gib Morgan have been retold and added to. They continue to survive as a colorful bit of American folklore.