The eight years that followed the 1954 crisis appear in retrospect as a period of transition. The market underwent a purge and a restructuring and a new generation of superheroes arose. Although their appearance was progressive and, at first, without great fanfare, the superheroes blazed the trail of a genre destined to definitively impose itself in the North American comic book industry, to the point of eventually supplanting the funny animals and humor comics that had been synonymous with comic books for over twenty years.

If the moral panic about comic books dealt a fatal blow to the industry, its consequences were not as monolithic as most commentators have implied. Fifteen of the forty-two publishers did go under during the summer of 1954.1 Deprived of over a third of its representatives, the comic book industry found itself perceptibly weakened. In this regard, the meeting that gathered twenty-four of the twenty-seven surviving publishers’ representatives of engravers and printers in New York on September 7, 1954, was altogether symbolic: it gave birth to the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA), the trade association whose primary mission was to issue a self-regulatory code that would keep comics books from falling back into the excesses that had led to their public demonization. The fathers of the CMAA were the heads of the four main comic publishers: John Goldwater, owner of Archie Comics, was president; Jack Liebowitz, cofounder of DC, was vice-president; Martin Goodman, founder of Marvel, was secretary; and Leon Harvey, owner of Harvey Comics, acted as treasurer.

Three publishers refused to join the new organization. Dell, which had always vigorously denied having anything in common with the publications that had come under attack during the Senate hearings, staunchly turned down any association with companies that had given in to crass commercialism (which was not without a certain irony: Dell also issued all sorts of paperbacks whose covers and titles were often anything but tame). Gilberton, whose Classics Illustrated line had been a consistent best seller since the war, also refused to join the CMAA because they did not want to take the chance of sullying the educational image of their publications by associating with controversial publishers. EC was no member either (at least at first): Gaines considered the self-censoring code as a hypocritical masquerade to which he would not be a party under any circumstances. In the absence of these three publishers, the CMAA represented less than two-thirds of the industry’s sales volume (Dell practically represented one-third on its own). Whereas EC effectively suffered because its magazines did not bear the Comics Code seal of approval (Gaines finally joined in the vain hope of saving his comic book line), Dell and Gilberton continued on in the second half of the 1950s without being hurt by their nonmember-ship in the CMAA.

The founders of the CMAA knew that their organization would need to be legitimized by the presence at its head of an industry outsider with impeccable credentials. They thus approached Fredric Wertham, who flatly declined their offer because he felt that the comics publishers’ association was merely a front that would continue to exonerate the abuses that he had denounced in his screed Seduction of the Innocent. The executive secretary finally appointed by the CMAA executive was Judge Charles F. Murphy: a municipal New York magistrate, who was an active but otherwise ordinary participant in the struggle against juvenile delinquency, was a perfect Catholic husband and father and a perfect choice to act as moral guide to the publishers.2 His appointment was announced on September 16, 1954, and he started his two-year stint on October 1, 1954. Even before this date, he announced that he planned to clean up the contents of comics. He drafted the self-regulation code signed by twenty-six publishers on October 27, 1954. Finalized in collaboration with Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish ministers and representatives of mothers’ associations, the text prohibited all that was reprehensible and indecent in comic books.

In its initial form, the Comics Code included a preamble, a section on editorial content, and another on advertisements (see appendix). The preamble, expressing the point of view of the industry leaders at the head of the CMAA (Archie, DC, Harvey, and Marvel), extolled the virtues of comics as an exceptional educational medium and of self-regulation as a development strategy. The principal subjects tackled by the code were delinquency and its representation (twelve articles), horror (five articles), and a series of recommendations about the decency of dialogue (three articles), references to religion (one article), the representation of nudity and the female body (four articles), marriage and sex (seven articles). The section on advertising prohibited any propaganda for tobacco, alcohol, firearms, and gambling; it also forbade all publicity for fireworks, books about sex, or books containing reproductions of “nude or seminude figures,” or “medical, health, or toiletry products of questionable nature.”

The publishers were to submit the artwork intended for publication to the CMAA, who would review the pages and, if necessary, make modifications. Whenever a detail—a gun, cleavage, the curve of a breast—or an entire strip required “touching-up,” the artwork was reviewed a second time in order to receive the Comics Code Authority’s stamp of approval. The very comprehensive nature of the restrictions explains why many industry actors were hit so hard. Starting in January 1955, every comics magazine published by the CMAA members was to carry the rectangular seal signaling that it had received the association’s imprimatur. Simultaneously wholesalers and retailers were informed that they did not have to sell comic books that did not carry the seal of approval. This brought Gaines to subsequently join the CMAA, as an increasing number of his packages were returned unopened. As he had to cancel the horror titles, which formed EC’s financial backbone but infringed the Comics Code from cover to cover, he was unable to maintain the rest of his line without them and released new, code-compliant titles that did not meet with any success.

Despite a seemingly promising start, it soon turned out that the CMAA would tolerate too many things. The relationship between Charles Murphy and the CMAA executive deteriorated as he realized that the authority with which he was invested did not enable him to enforce the code strictly. In September 1956 Murphy announced that he would not seek to renew his position at the end of his contract. To replace him, CMAA president John Goldwater contacted Mrs. Guy Percy Trulock, the former president of the New York City Federation of Women’s Clubs. She accepted the post but from then on the censoring chores were turned over to CMAA attorney Leonard Darvin.3

Starting in 1955, the new context following the introduction of the CCA brought about various changes: the old order that had coalesced from 1934 to 1954 had run its course and a new era began for comic books. The overall comic book output shrank considerably while several publishers went into decline. What was the actual economic impact of the Comics Code? Most of the authors that have addressed this question have simplified the picture by emphasizing the implementation of a censoring system that precipitated the demises of many publishers. While superficially acceptable, this interpretation is insufficient if one tries to draw conclusions on the reconfiguration of the industry after this upheaval.4

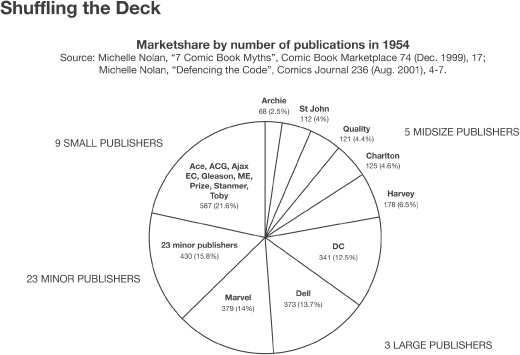

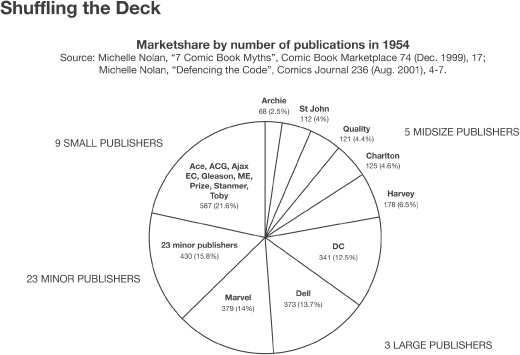

Approximately 2719 comic books (give or take a few issues whose existence is uncertain) were published with a cover date between January and December 1954 (available on newsstands between October 1953 and September 1954). As far as the number of new releases by publisher was concerned, the market broke down into four types of participants, by order of increasing size:

• twenty-three “minor” publishers, whose combined output was 430 comic books (15.8 percent); among them were Fawcett and Fiction House, two former big players whose comic book publishing activity ceased at the start of 1954;

• nine “small” publishers (ACG, Ace, Ajax, EC, Gleason, Magazine Enterprises, Prize, Stanmor, Toby), whose annual output ranged from 53 to 77 comic books for a total of 587 (21.6 percent);

• five “medium-sized” publishers: Harvey (178 releases), Charlton (125), Quality (121), St. John (112), Archie (68) accounted for 22.2 percent;

• three “big” publishers—Marvel (379), Dell (373), DC (341)—accounted for 40.4 percent of all new releases.

The above figures concern the number of releases, not the print runs. Even if it was possible to observe a correlation between the number of releases and circulation for most of them, a publisher such as Archie would have probably come fourth behind the three “majors” in terms of sheer circulation although it issued only 68 comic books with 1954 cover dates.

What exactly happened to the publishers after the creation of the Comics Code? The eight largest publishers were not immediately affected: the only two that did not reach the 1960s were Quality, bought up by DC at the end of 1956, and St. John, who progressively scaled down its output until it closed down in 1958. The small publishers were comparatively, and predictably, hit harder: other than Prize and ACG, who lasted until 1963 and 1967, respectively, they folded in succession: Toby and Stanmor in 1955; Ace, EC, and Gleason in 1956; Ajax, Magazine Enterprises, and St. John in 1958. The toll was particularly high among the minor publishers because many of them published mainstream periodicals and comic books were for them essentially a source of extra profit that was not worth the risk of commercial boycott (like Ziff-Davis who closed its comic book branch in 1957); the other small publishers were tiny outfits created after the war to cash in on what then seemed to be an uninterrupted sales boom.

As a matter of fact no “big” publisher suffered from the Comic Code crisis, at least in the first place. The small and the very small publishers were the most immediate victims. Among these were two players whose importance had greatly exceeded their actual weight: EC, the actual target of the CMAA executive who blamed Bill Gaines for the negative publicity heaped on the industry following the spring of 1954 Senate hearings, and, to a lesser extent, Lev Gleason, the original promoter of crime comics. Out of the 13,668 comic books published from 1950 to 1954, EC only issued 263 (less than 2 percent and in comparatively small print-runs for that time). As for the other minor publishers their demises had little, if any, impact on the industry, in the short or long term. Whereas EC stood out by resorting to carefully selected talents, the other companies churned out second-rate fare that at best plagiarized the larger publishers’ titles. This does not mean that the larger publishers always produced better comics. Far from it. But they did not have to fear the appearance of a system of prior censorship that would undeniably imperil the smallest competitors whose precarious financial balance relied on comic books with “questionable” content. Because of the sometimes enormous differences among publishers one should nuance the interpretation holding that the establishment of the CCA unilaterally wrought havoc in the industry.

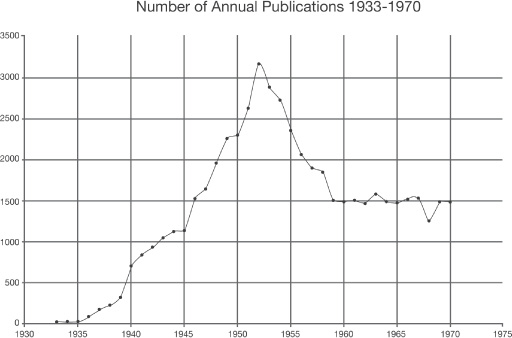

The sudden drop of the industry’s output after 1954 is another idea that must be handled with caution. As the following graph shows, the economic peak of the industry was 1952, when 3161 comic books were published for an overall circulation around 1 billion: for want of reliable figures, the existing estimates range from 840 million to 1.3 billion copies.5 The reader should try to imagine that 1952 comic book buyers were offered an average sixty titles every week: back in those pre-specialty-store days the comics put out by the smallest publishers must have been practically impossible to get hold of outside of large cities and, even there, purchasing every new title (providing anyone ever tried to do so) was also a challenge! After 1952, the annual number of releases dropped every year: 2880 in 1953, 2714 in 1954, 2351 in 1955, 2054 in 1956, 1908 in 1957, 1856 in 1958, and 1512 in 1959 (approximately the 1946 level). The drop accelerated after 1954 with net decreases in the annual number of releases in 1955 (minus 370) and 1956 (minus 300). It slowed down in 1957 (minus 150) and 1958 (minus 50) before resuming with a net loss of 346 releases in 1959. By the 1960s the trend leveled off around 1500 yearly releases. What to conclude from these numbers?

The collapse in the annual number of comic book releases began one year before the Comics Code crisis: the events of 1954 actually took place against the backdrop of a steady erosion of the supply that lasted until the end of the decade. Certainly, it is possible to imagine that the events of 1953 would have been only temporary if the moral panic of 1953–1954 had not already damaged the market. But this market was never stable! What we can know about the combined circulation of all comic books, thanks to the admittedly incomplete data available in the periodicals directory Ayer’s Guide, shows a switchback market since 1945: a continuous increase of print runs until 1948 was succeeded by a two-year drop. Circulation shot up dramatically in 1951 and 1952 before falling back abruptly to the 1950 level in 1953 and hitting bottom in 1954, when circulation was back to the 1945 level. From the following year, print runs increased again and leveled off around values close to those of 1946 throughout the 1960s.6

The “crisis,” in the economic sense of the term, debuted in 1953, when the declining number of new releases combined with a precipitous collapse of circulation figures. What was so special about this year? In ideological and political terms, the United States had taken a conservative turn with the inauguration of Republican president Dwight Eisenhower. In cultural terms an important factor was the spectacular rise of television: 23.5 percent of American households owned a television set in 1951 compared to 34.2 percent the following year. The new appliances had rapidly modified the organization and uses of spare time in American families. From the start of the 1950s onward, the most determinant factor for the purchase of a television set was not the household’s revenue or social class but the presence of children, who had so far been the largest segment of comic book readers.7

Another element worth mentioning is that the supply of comic books had skyrocketed in 1951–1952 and probably reached the upper limit of what demand could absorb—or, precisely, could not absorb. This may explain why the drop in monthly circulation between 1952 and 1953 (minus 30 percent to 40 percent) was much sharper than the drop in the number of releases (minus 9 percent). In fact, by 1953, the publishers seemed to have reduced print runs across the board, as if to adjust to a contracting demand. However the demand was not diminishing for demographic reasons: the postwar baby boom was at its height then and, logically, the rising number of children should have increased the demand for comic magazines until the 1960s. But it was not so: while more than 23,000 new comic books were issued from 1950 to 1959, less than 15,000 came out from 1960 to 1969. As a matter of fact the number of releases fell by a third from one decade to the next, although the United States was going through the most rapid demographic growth in its history (+19 percent in the 1950s, +13 percent in the 1960s). These figures simply show that the public’s loss of interest in comic books was a long-term trend whose first signs had been perceptible since 1953 and would probably have been even more conspicuous if the American population had not grown so dramatically during the postwar decades.

The economic trend was amplified by a political will. The supply collapsed in 1956 and not in 1955, because the staggering blow dealt to the industry was New York’s adoption of a bill that partially prohibited the sale of comic books to children, a legislation recommended by Fredric Wertham since the end of the 1940s. As of July 1, 1955, a law in two sections was enforced in New York: the first section prohibited the publication and distribution of any book, brochure, or illustrated magazine whose title contained the words crime, sex, horror, or terror and whose contents were devoted to the description of acts relative to the four incriminating terms; the second section forbade the sale or possession with intent to sell to persons under eighteen of obscene movies, photographs, pocketbooks, or comic books. This legislation resulted from the work conducted since 1949 by the State’s “Joint Legislative Committee To Study the Publication of Comics”; its two previous versions were vetoed by Republican governor Thomas Dewey, a fierce advocate of freedom of speech, in 1949 and 1952 but the third one was ratified by Dewey’s successor, Democrat William Harriman. This law proved as effective as, if not more effective than, the CMAA’s self-regulation code in terms of cleaning up an industry almost entirely based in New York.8

Distribution was the last factor that contributed to the comic book industry’s decline. The June 4, 1954, Senate hearings singled out many unsavory commercial practices of press wholesalers that were close to blackmail and extortion. These disclosures cast press distributors in a bad light and indirectly impacted publishers. When wholesalers ceased to practice tie-in sales, the supply of comic books dropped because retailers were then free to return all the titles they did not wish to carry. It became clear afterward that the dramatic growth of the industry in the last decade had partially rested on a supply that was artificially maintained. As it stands, the crisis of 1954 was less a conjunctural obstacle to the growth of the comic book industry than the catalyst of a latent crisis.

Thus it is naive to affirm that only the Comics Code crisis brought about the lasting marginalization of comic books in the cultural consumption of young Americans. The crisis had only two objective consequences: first, the temporary disappearance of horror comic books (until Warren resurrected them in 1964) and the definitive departure of crime comics; second, the renewed supremacy of the publishing houses that would dominate the mainstream market during the 1960s (Archie, Charlton, DC, Dell/Western, Harvey, Marvel).

From 1955 a new group of publishers led the market: if one sets aside the outsider Dell, who remained the industry’s unchallenged leader in sales thanks to its titles for preadolescents, and the unsinkable Gilberton, whose Classics Illustrated comics were used by all American schoolchildren to write their English literature assignments, Charlton, Archie, DC, Harvey, and Marvel came out as leaders of the post-1954 industry. Charlton was a generalist outfit based in Connecticut who had been publishing comic books since 1946 and experienced a dramatic growth in 1954 after buying up Fawcett’s comics properties. The four others were the actual orchestrators of the CMAA, those who had the most to gain in the first place from the establishment of a self-regulation system largely echoed by the media. All of them easily adjusted to the Comics Code Authority’s demands and thereby opened up a new chapter in the history of comic books.

An overview of comic book genres (by number of titles) showed three categories in the second half of the 1950s: most numerous were the funny animal titles, humor, TV, western, and romance comics; in intermediary position were teen comics, fantasy, detective, and war titles; the least represented genres were adventure, superheroes, science fiction, and newspaper comics reprints. This last genre, which had given birth to comic magazines twenty years earlier, had been declining since the late 1940s. Its symbolic demise occurred with the last issue of Famous Funnies, when Eastern Color ceased its publishing activity in the spring of 1955.

Just as many publishers found themselves with a then useless backlog of unpublished war stories by September 1945, a similar problem happened in January 1955 when the rules of the Comics Code came into force. Although it was always possible to draw clothes on a seminude body or to white out a weapon, most horror stories could not be touched up so as to become acceptable to the CCA administrator. Just as the strict enforcement of the Hays Code in Hollywood was accompanied by an impression of relative dullness of new movies in the years after 1934, the new approach to comic book genres was no longer structured around what could be shown but rather what could not be shown in panels. Four new currents became prominent in the second half of the decade.

The first two were genres that had been moderately successful up to that point but which gained new visibility. War stories were accepted by the CCA because the violence depicted in them was not associated with delinquency or crime. Science fiction possessed a considerable potential for escapism and made it possible to tell thrilling stories without violence (such as in DC’s Tales of the Unexpected); one unmistakable change in these comics was the female characters’ clothing, much less tight-fitting than in the past. Two new genres made their appearance: the first, mystery, rose from the ashes of horror comics, with scary stories that featured neither misshapen nor monstrous creatures, nor blood nor graphic violence, but suspense and ghosts of all types. The launch of DC’s The Brave and the Bold #1 (August 1955) in the spring of 1955 marked the return of historical adventure, a genre that the company had used a great deal until the war but given up afterward for less didactic fare. Marvel introduced a genre halfway between fantasy and science fiction that was its stock-in-trade for five years: monster comics. Taking advantage of a loophole in the list of monstrous creatures prohibited by the Comics Code, these titles cashed in on the short-lived fad of American and Japanese movies featuring testy gigantic creatures of extraterrestrial, subterranean, or underwater origin.9

Genres anterior to 1955, such as western and romance, continued their trajectories in stories watered down to comply with the code. The material for young children and educational comics remained steady sellers: Dell and Gilberton held their privileged positions in the market, although Harvey started sneaking into the opening left by Dell thanks to comics featuring its animated cartoon properties. Unlike its rivals who had as a rule specialized in one or two genres (such as humor and teen comics at Archie, western and science fiction at Marvel), Charlton was a jack-of-all-trades of comic books. This family-owned publishing house, for which comic books were just one type of periodical among others, was probably the most visible publisher of illustrated magazines with Dell and DC during the second half of the 1950s. Yet DC played a crucial role in the evolution of the market when it relaunched the superhero genre, at first very quietly.

For most comic book historians the “Silver Age” began with the first appearance of the modern Flash in Showcase #4 (October 1956), a comic that hit newsstands early in the summer of 1956. During the first half of the 1950s, superheroes had become a minor genre, a subcategory of adventure stories then as marginal as jungle and aviation stories (even though all three genres were instrumental in the emergence of the industry in the late 1930s). Only DC’s three pillars—Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman—experienced a durable, if not exceptional, popularity, having graduated from mere property to iconic status by the turn of the 1950s. The nadir of the genre was between 1950 and 1952, when all attempts at publishing superheroic material failed. Nineteen fifty-three was a turning point with the demise of Fawcett, which led to the cancellation of all Captain Marvel titles,10 and the launch of the television series The Adventures of Superman. To cash in on the success of this program, Marvel published new stories starring its great stars of yesteryear: Captain America Comics, The Human Torch, and Sub-Mariner Comics debuted in 1954 but their momentum was broken by the Comics Code crisis. Similar attempts by lower-profile publishers Sterling, Magazine Enterprises, and Farrell proved just as disappointing.

DC was more successful in its revamping of superheroes. In the spring of 1954 it released Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen, a title that aimed to reach the same preadolescent and adolescent markets as Superboy by featuring the young Daily Planet photographer-journalist who happened to be the only recurring juvenile character of the Adventures of Superman show. Three years later, Superman’s eternal female foil Lois Lane was spotlighted in Showcase #9 and #10 before becoming the main character of Superman’s Girlfriend Lois Lane in January 1958, just as the television series ended its run. This title appealed to readers of both sexes for many years but it was in response to female readers’ requests that DC created a new character attached to Superman for the first time since Superboy in 1949. In Action Comics #252 (May 1959), the Kryptonian hero discovered a distant cousin newly arrived to Earth and endowed with the same powers as him: unlike Lois, “Supergirl” was not given her own title but was a long-standing backup feature in Action Comics.

The introduction of a modernized version of the Flash in Showcase #4 has more value as a retrospective symbol than as an event in and of itself. For one thing the actual first superhero of the new generation appeared four months before Flash: it was J’Onn J’Onzz, the Manhunter from Mars, the protagonist of an inconspicuous backup story at the end of Detective Comics #225 (November 1955). The new Flash was no overnight sensation: two years went by before he was given his own title. It was really a minor event by the pre-1955 standards, when any new genre was immediately picked up by competitors.

DC’s Showcase was emblematic of the new market conditions. As its name indicated, this title featured new concepts in order to test them and exemplified an infinitely more prudent approach to the market. After three unconvincing issues, this comic book successively gave DC the Flash (#4), the Challengers of the Unknown (#7), Lois Lane (#9), Space Ranger (#15), Adam Strange (#17), Rip Hunter (#20) and the new Green Lantern, who made his first appearance in the twenty-second issue (September 1959), exactly three years after the Flash.11. The relaunch of superheroes was a slow process in all respects: Showcase, its main vehicle, was a bimonthly title; Lois Lane and the Challengers of the Unknown did not receive their own titles until the start of 1958, whereas the Flash received his at the end of that year. The start of 1958 also saw the birth of a new concept designed to attract young readers: starting with issue #247 (April 1958), Adventure Comics featured The Legion of Super-Heroes, a team of young thirtieth-century superpowered teenagers including Superboy. By 1959 it became clear for DC and its competitors that superheroes once again attracted readers after a dozen years’ hiatus. Archie tried to cash in on the revived genre by hiring Joe Simon and Jack Kirby to create The Fly and The Double Life of Private Strong. The following year, Charlton offered Captain Atom in Space Adventures #30 (March 1960), while Green Lantern and The Justice League of America (the team including Aquaman, Flash, Green Lantern, Manhunter from Mars, Wonder Woman, and occasionally Batman, Green Arrow, and Superman) received their own titles. According to a reader’s poll published in Green Lantern #3 (December 1960), Green Lantern was the first new character to experience considerable popularity.

Several reasons account for the successful revival of the superheroes. First the late 1950s space race provided the backdrop to a new worship of heroes and outstanding individuals: the exploits of Yuri Gagarin had proved that a communist could be a genuine hero of modern times and of science. The recuperation of this theme by American popular culture lent new relevance to the myth of American heroism, which was then suffering from the progressive exhaustion of the western genre. Second, the lasting success of Superboy prompted DC editors to create characters based on the stereotyped adolescent featured in television series and Hollywood comedies: in an era when consensus was still anchored in ambient discourses (and the CCA saw to it that comic book contents remained consensual), the new superheroes were models of individuals complying with social norms and bent on preserving the status quo. Finally, DC set out to upgrade the artwork and covers of its magazines and, for the first time since the apogee of EC in the early 1950s, implement an embryonic star system in which a lead character became associated with a quality illustrator; to cite only the most prominent, Carmine Infantino’s name became indissociable from the Flash, and the same happened with Gil Kane and Green Lantern, Curt Swan and Superman, and Joe Kubert and Hawkman.

The turning point was aesthetic and conceptual. The new comic books and the new heroes broke with the assembly-line model, without any regard for the final product that had plagued comic books for years (EC having been an exception in its heyday). A clear symptom of the changes in the making was the introduction by editor Mort Weisinger of a letters page in the titles starring Superman in 1958.12 This practice, hitherto uncommon in comic books, soon spread across the DC line and was picked up by other publishers: by devoting a page to opinions on the magazine, a new type of proximity arose between readers and publishers. Nonetheless DC was not destined to become the most brilliant representative of the new era that comic book historians retrospectively named “The Marvel Age.”

In 1957, the publishing house founded twenty-five years before by Martin Goodman almost disappeared. Because of the chronic absence of editorial direction in its comic book line—comics were one among many types of magazines churned out by Goodman and his only policy toward funny books had always been to imitate the competition’s best-selling titles—comic sales had markedly slowed down by 1956. To weather the crisis Goodman canceled fifty-five titles out of nearly a hundred and closed down Atlas, the distribution branch of his company, to sign an account with the large national distributor American News. Unfortunately, American News went under a few months later. To avoid disappearing, Goodman had to fall back on Independent News, the distributor associated with DC, which forced him to accept a contract that limited Goodman’s comic book output to eight monthly titles.13

Since 1945, Goodman’s comic book editor had been Stan Lee, a cousin to his wife who had worked for him since 1939. When the company was in trouble in 1957, Lee reportedly saw Captain America cocreator Jack Kirby walk into his offices looking for freelance work. Kirby was given a free hand to revamp the comic book line edited by Lee and set out to produce an impressive number of short fantasy stories, many of which starred extraterrestrial monsters. The second great draftsman associated with Marvel at the same time as Kirby was Steve Ditko: a survivor of the large-scale layoff of 1957, he produced stories featuring protagonists involved in supernatural or unusual situations. Kirby’s powerful, superlative style was a perfect counterpoint to Ditko’s taut, fluid linework. The two illustrators became the pillars of Marvel while Carmine Infantino, Gil Kane, and Joe Kubert were DC’s top artists.

Until the summer of 1961, Marvel essentially produced fantasy titles containing short stories. Fantastic Four #1 (November 1961), the first Marvel title starring superheroes in over six years, was released in August. The following year saw the successive appearances of The Incredible Hulk, Thor, and in the summer, The Amazing Spider-Man. All were drawn by Kirby except Spider-Man, which was assigned to Ditko. These colorful characters living adventures where high-powered action combined with soap opera realism formed the core of a graphic and narrative universe that was to give a second breath to Marvel and superheroes in the American comic book industry.

At the dawn of the 1960s superheroes were not one of the short-lived genres whose succession had shaped the history of the comic book industry so far. Instead they epitomized the beginning of wide-ranging changes among comic book readers. The renewal of DC and the unexpected resurrection of Marvel coincided with the decline of Dell. By the late 1950s the company that had headed the industry since the war saw its sales decrease gradually, mainly because of the blows felt by regional distribution networks following the demise of American News in 1957. To make up for the loss of revenue, Dell increased the cover price of its basic comic books to fifteen cents in 1961, a move postponed by all publishers since the advent of for purchase comic magazines twenty-eight years before. Although the price hike was recommended by a market study, the results were disastrous: the sales of all Dell titles collapsed in front of competitors that still retailed for a dime. Because this crisis took place after several years of rising tensions with Western, Dell decided not to renew the contract of its supplier: by 1962, Western initiated a partnership with Whitman, a Wisconsin publisher with which it launched Gold Key, the imprint under which were released all its erstwhile Dell titles, while Dell started a comic book branch under its own name.14

Nearly all publishers increased their cover price to twelve cents by 1962. Yet, the fairly quick collapse of Dell confirmed that comic books were no longer the privileged pastime of children, their traditional readers. Silver Age superheroes did not embody a return of American comic books to their own wartime past but rather a new sensibility in popular culture. Marvel and, to a lesser degree, DC propagated a “new” genre tapping all the sources of ambient discourse (about youth, the middle class, nuclear power, the space race), the grand visual design of Hollywood blockbusters (such as Cecil B. DeMille’s 1956 sword-and-sandals epic The Ten Commandments), and a scientific imagination still largely absent from television programs. Thanks to this originality, the new superheroes were about to leave their mark on the 1960s.