The short period in the 1960s addressed in this chapter was a creative phase whose effects are still felt in the comic book industry in the early twenty-first century. The industry’s new dynamic, both commercial and cultural, coalesced around two leading publishers (Marvel and DC) and the superhero genre. Just as important was the advent of a new conception of comic books epitomized by the first generation of creators that had grown up with them. The newcomers proceeded to overhaul the codes and contents of the medium that had most strongly fashioned their cultural universe. While the most radical among them produced the first “underground” comics, the most mainstream creators brought visual experimentation to Marvel and DC.

The steady drop in the annual number of new releases that had started in 1953 came to an end in 1960, when it leveled off around 1500. This figure was equivalent to the 1946 level but only half of the 1952 level. Until 1970 the only notable jolts were a peak to 1590 in 1963 and a dramatic slump to 1260 in 1968 following the end of the short-lived but frantic fad around the television series Batman. Combined print runs oscillated between 25 and 30 million copies from 1962 to 1968, then around 22 million until 1970 (exclusive of underground comics). The best year was 1966 with 30 million comic books printed for a readership suddenly enlarged by the media hype surrounding Batman, which benefited the entire industry but only for a limited time.

As the hierarchy of genres continued to evolve, the industry looked increasingly different from what it was like during the prodigious postwar decade. In number of titles, the most minor genres during the 1960s were science fiction, fantasy, and crime—crime comics went through a long decline because of the Comics Code and the competition from television series. War, romance, and western comics fared slightly better. The leading genres were still funny animals (dominated by Gold Key), humor series with or without adolescent protagonists, film and television adaptations (a lucrative niche hotly contested by Dell and Gold Key), and superheroes. Literally rising from its postwar ashes at the end of the 1950s, this latter genre experienced a permanent ascension throughout the decade before becoming hegemonic in comic books for the last thirty years of the twentieth century.1

The renewal of DC superheroes spanned a five-year period from the appearance of the new Flash in the summer of 1956 to that of the new Atom in the summer of 1961. Modern versions of older characters (Flash, Hawkman, Green Lantern, among others) alternated with new protagonists issued from science fiction, the literary genre of which DC’s main three editors (Mort Weisinger, Jack Schiff, Julius Schwartz) had been hardcore fans since the 1930s. While they were not superheroes per se, characters such as the Space Ranger and Adam Strange (created in 1958) or the postatomic team of the Atomic Knights (created in 1960) were basically costumed crime fighters whose adventures were likely to appeal to the same constituency. After the summer of 1961, DC ceased to introduce notable new characters for a long time. The only remarkable innovation in the following years appeared in the spring of 1963; the Doom Patrol was a team of superheroes whose lives had been disrupted with the acquisition of their powers—a concept that echoed the Marvel superheroes’ difficulty in handling their own extraordinary capacities. One year later, starting with Detective Comics #327 (May 1964), editor Julius Schwartz revamped the Batman mythos by recasting both him and his sidekick Robin as “realistic” detectives thanks to the slick art of Carmine Infantino and clever writing of John Broome.

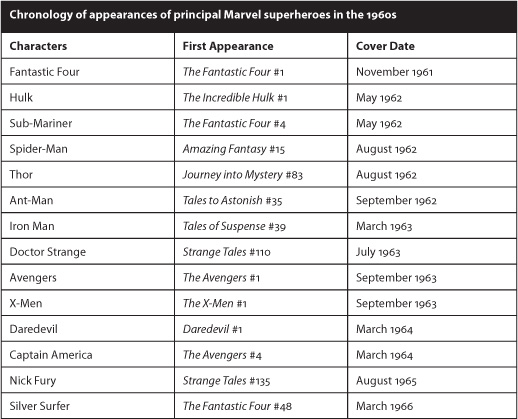

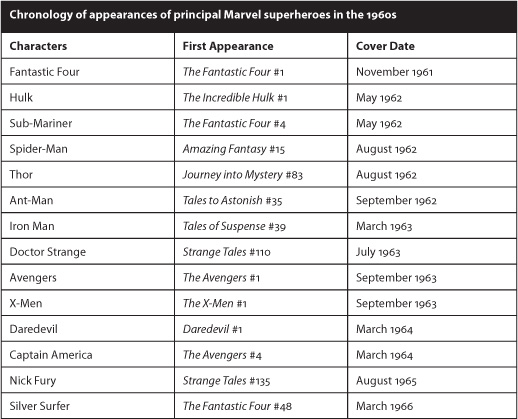

Taking advantage of the boost given to the superheroic genre by DC since 1956, Marvel took only two and a half years, from the appearance of the Fantastic Four in the summer of 1961 to that of the blind superhero Daredevil at the end of 1963, to create the core cast of the “Marvel Universe”: among the characters that appeared in the second half of the decade, only Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., a high-tech secret agent, and the atypical Silver Surfer were to become first-tier protagonists in the long run.

The increasing popularity of Marvel and DC characters and of Gold Key’s Doctor Solar Man of the Atom, a title launched in 1962 whose protagonist was a partial plagiarism of Captain Atom created for Charlton by Steve Ditko in 1960, alerted other publishers to the potential of a genre widely regarded as irremediably passé for the past fifteen years. Nineteen sixty-five witnessed a quantitative peak: ACG, Archie, Charlton, and Harvey launched their own superhero titles, and a newcomer, Tower Comics, released a line whose flagship title T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents seemed capable of competing with Marvel and DC. Tower comic books were produced by the studio of Wallace Wood, assisted by Reed Crandall, Dan Adkins, and occasionally by such talented collaborators as Gil Kane and Steve Ditko.2

By the mid-1960s comic books became fashionable. While the pop art avant-garde cast a new, although not necessarily positive, glance at the material that Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol used in their own works, journalists covered the first comic book conventions (starting in 1964) with considerable condescension and were seemingly shocked to discover the high prices fetched by collectible comic books. Thousands of baby boomers then entering college had grown up reading comic books and watching television and responded with enthusiasm to the narrative innovations of Marvel’s new superhero comics. On October 16, 1965, a memorable concert-dance-happening entitled “A Tribute to Dr. Strange” took place in San Francisco; the homage paid to Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s magician was limited to the name given to the event and the psychedelic ambience reminiscent of the mystic dimensions through which this character traveled.3 The comic book fad soon hit the general public thanks to the bewildering popularity of ABC’s Batman. After more than a decade of goofy stories involving aliens and talking animals invariably signed by the character’s creator Bob Kane yet ghosted by an array of anonymous writers and artists, Julius Schwartz’s new direction had turned the caped crusader into an attractive property that soon drew the attention of William Dozier, a television producer on the lookout for a concept likely to boost the slow ratings of the ABC network. After picking up comic books to read on a plane Dozier discovered the revamped Batman and hit on the idea of turning the dynamic duo into TV stars. The series aired on Wednesday and Thursday nights beginning on January 12, 1966. Ironically the campy slant worked into the show was a return to the pre-Schwartz Batman but it proved tremendously successful for two years.

The circulation of the Batman comic book doubled to almost nine hundred thousand monthly copies. Yet all superheroes and the entire industry benefited from the “Batmania” for close to a year and a half. Simultaneously, the visibility of Marvel characters was kept high with young children by an animated cartoon series shown on Saturday mornings between 1966 and 1970. New publishers appeared following in the footsteps of Tower: King Features and M. F. Enterprises in 1966, Milson in 1967. These two years were the high economic point of the 1960s for the crime-book industry but the frenzied collective passion for the Batman TV show collapsed as suddenly as it had appeared (the last episode was telecast on March 14, 1968).

Starting in the summer of 1967, the industry entered a slump. It hit all publishers except Marvel, whose sales kept up and overtook DC’s for the first time since 1953. The newcomers disappeared in a few months, and, in their fall, took the venerable publishing house ACG with them. Tower survived until 1969 but folded due to poor management. Nineteen sixty-eight witnessed the apparently irresistible growth of Marvel, after the contract that linked it to the Independent News distributor came to an end. A new partnership with Curtis Distribution allowed Marvel to give their own titles to first-rank superheroes hitherto featured in old fantasy titles (i.e., Thor had appeared in Journey into Mystery since 1962, Iron Man in Tales of Suspense since 1963) and spotlight secondary characters in their own magazines. Eight titles and one black-and-white magazine were added to Marvel’s output. To counter the growth of its longtime competitor who had regained the ground that it had lost ten years before, DC initiated a domestic revolution in 1967 by promoting illustrator Carmine Infantino to the post of “editorial director.” Infantino completely altered DC’s old corporate mind-set by appointing other illustrators to editorial positions (Joe Kubert, Mike Sekowsky, Dick Giardano, Joe Orlando, among others). The new editorial personnel were expected to produce comics that would attract the readers of Marvel titles, nowadays no longer receptive to the work of the older generation of editors (notably Mort Weisinger and Jack Schiff) and writers (such as Gardner Fox, France Herron, or Otto Binder) who had debuted in the 1940s. As inventive and original as the new characters that appeared in DC titles in the late 1960s were (such as Deadman or the Creeper), the tables did not turn: new Marvel comic books averaged four hundred thousand copies, twice the typical print run of DC titles.

Unlike most of their competitors, who were small companies, the Big Two of the 1960s were large operations whose activities exceeded comic book publishing. DC (created in 1937) was the publishing branch of National Periodical Publications (NPP), a conglomerate including Independent News Company (created in 1932), which became the largest national distributor of paperbacks and magazines following the failure of American News in 1957, and Licensing Corporation of America (created in 1940 as “Superman, Inc.”), which handled the merchandising of DC properties. NPP was the corporate empire spawned by the publishing-printing house owned by the Donenfeld family in the late 1920s and managed by accountant Jack Liebowitz. In 1961, NPP went public after accumulating considerable revenue thanks essentially to its distribution and licensing branches. In July 1967, the high-profile visibility of the Batman television series, the media hype about comic books, and the company’s overall prosperity prompted the Kinney conglomerate (a stockholder of maintenance, funeral, and automobile rental companies, among others) to announce its intention to acquire NPP. The merger took place in March 1968; Jack Liebowitz entered Kinney’s board of directors and he was replaced as DC president by Paul Wendell, who had until then been the company’s chief accountant.4 The following year, Kinney acquired the Warner studios and originated the creation in 1972 of Warner Communications, the ancestor of today’s Time-Warner. Hence in 1968 DC became a small part of a huge company where the important decisions were made at several echelons higher than the editorial level. But the latter could take advantage of some leeway for another few years.

Unlike DC, since November 1956 Marvel had been only a publishing company since November 1956, when Martin Goodman had closed down his deficit-ridden distribution branch Atlas News to become a customer of the national distributor American News just months before it went under in April 1957.5 Behind the Marvel imprint were in fact several companies (Atlas Magazines, Leading Magazine Corporation, Official Magazine Corporation, to name a few) that allowed for considerable legal and financial flexibility. Yet comics were just one segment of the company’s output: of the fifty periodicals issued by Marvel in 1968, over half were crossword puzzle, humor, film, and men’s magazines.6 In the fall of 1968 Goodman sold the company he had created in 1932 to Perfect Film and Chemical, a conglomerate that was buying up media companies. The publishing house was renamed “Magazine Management” and became part of the same corporation as the Curtis distribution company. Goodman remained president and publisher and Stan Lee editor in the new company.

DC and Marvel had changed hands at the best moment for their original owners. In 1969, the euphoria of the previous three years was petering out. The superhero boom began to lose momentum and no new genre was on the horizon. In the preceding year, Classics Illustrated, one of the survivors of the first age of comic books, had raised its cover price from fifteen to twenty-five cents to make up for slowing sales. Gold Key also hiked its cover price from twelve cents to fifteen cents. Marvel, DC, and the rest of the industry followed suit in 1969. Meanwhile, Warren’s black-and-white horror magazines, whose format exempted them from complying with the Comics Code, had been selling very well since 1964. Just as mainstream comic books were about to enter a difficult decade, a new genre of comic book was developing without any economic connection to the thirty-five-year-old comic magazine industry—underground comics, also known as comix.

Underground comics were the offspring of two creative movements linked to the beginnings of the counterculture in the 1960s. First was the work of Harvey Kurtzman dating from 1957, and the second was the student press at the end of the 1950s.

In 1956, Harvey Kurtzman left the editorial direction of Mad following financial differences with William Gaines. Since the spring of 1955, Mad had become a twenty-five-cent black-and-white magazine. The new format had freed Gaines and Kurtzman from the Comics Code’s constraints and gave the magazine a broader scope than in its early comic book incarnation. It attracted an enlarged audience of adolescents over the age of fifteen years and college students, who would otherwise have been reluctant to purchase a comic book. Mad became a social phenomenon because its iconoclastic and subtly subversive discourse clearly responded to an actual need in an extremely conformist society. Despite Kurtzman’s departure, it thrived under the editorship of his successor Al Feldstein and became a fixture of the adolescent subculture, eventually making its publisher William Gaines very rich.

Kurtzman did not remain inactive. Just after his resignation, he was contacted by Hugh Hefner to edit a comics magazine likely to appeal to the readers of Playboy. The first issue of Trump came out in January 1957: between glossy covers, this luxurious fifty-cent magazine offered cartoons and strips by Jack Davis, Will Elder, Russ Heath, and Wallace Wood, all EC alumni that had followed Kurtzman, as well as illustrators Al Jaffee and Arnold Roth. Unfortunately Trump was canceled after its second issue as Hefner encountered temporary financial difficulties. Undeterred, Kurtzman and his team returned to the comic book format with Humbug, a self-published, cheaply produced magazine that came out in the summer and lasted just over a year. By late 1958 Kurtzman was unemployed again and it was only in the summer of 1960 that his new opus appeared, a magazine titled Help!

With the collaboration of Gloria Steinem (before she became famous) and Terry Gilliam (before he joined Monty Python), Kurtzman produced a revue that was to become one of the main inspirations of comix. Help! looked different from anything that had been done before, mainly because Kurtzman could not afford to hire professional cartoonists. That was also why he relied a great deal on fumetti, parodic photo-novels with zany dialogues staged and occasionally performed by then-unknowns like Woody Allen or John Cleese. Help! was also a springboard for young illustrators born during the war, for which comics had always been a passion. Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, Jay Lynch, and Skip Williamson published their first pages as professionals in Help! several years before becoming leading lights of underground comics.7

“Underground” comic books were a direct emanation of the independent press that appeared in the wake of the counterculture, that is, the ideological, social, and cultural rebellion of many baby boomers. After growing up in the oppressive climate of the cold war and the fear/fascination of the atomic bomb they embraced the irreverent comics of Harvey Kurtzman, the chaotic-comic music of Spike Jones, the disrespectful and caustic humor of Lenny Bruce, or Paul Krassner’s anarchic-satiric magazine The Realist.8 In the countercultural press, comics were a means of expression differing radically from writing and traditional editorial cartooning, a medium in which form and content could combine to express the refusal of established values. They thus took advantage of a legitimacy that had been denied them as long as they were cooped up in the daily press and in children’s comic books. The new comics developed in three main media: the student press, the underground press, and the comix.

In the late 1950s, the student press became the third medium (after newspapers and comic magazines) to welcome comics. The first comics published on a campus appeared in the University of Texas–Austin’s Texas Ranger, edited by Frank Stack and Gilbert Shelton between 1958 and 1962 with occasional contributions by Jack Jackson (later known as Jaxon). Around the same time, Joel Beck published his drawings in the University of California at Berkeley’s Pelican. In student papers comics appeared as a third form (in addition to text pieces and spot illustrations) having finally outgrown its traditional childlike connotations and now appearing in publications that were springboards for future journalists. The new attitude toward comics was confirmed in 1961 with the release in Gainesville, Florida, of The Charlatan, an independent national magazine for college students. Edited by Texas Ranger alumnus Bill Killeen, the new title granted considerable space to satirical comics.

Student newspapers remained privileged outlets for nonmainstream comics throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Yet their importance in the maturing process of young artists was never as crucial as in the first half of the 1960s, before the underground press emerged between 1964 and 1966 and its complex network enabled the rebellion born on campuses to organize and to expand its audience. Newspapers such as the Austin Rag, the Berkeley Barb, the Detroit Fifth Estate, the Los Angeles Free Press, the Michigan Paper, the San Francisco Oracle, and Philadelphia’s Yarrowstalks formed the core of the “Underground Press Syndicate”—the acronym “UPS” was deliberately identical to that of the United Press Syndicate—founded in 1966 by East Village Other (EVO) editor Walter Bowart. UPS aimed to disseminate the ideas of the emerging New Left by providing all countercultural periodicals in the United States and abroad with editorial material available from no other syndicate. In the late 1960s UPS had a membership of 350 American and European periodicals whose combined circulation amounted to five million copies.9

Underground comics were appreciated by UPS magazine editors because of their national, even international appeal, contrasting with the local flavor of much of the material. Like in early twentieth-century newspapers, comics were among the features that attracted buyers both domestically and abroad—for instance France’s leading underground magazine Actuel derived much of its success from its lasting reliance on Robert Crumb’s strips. In the United States the first comics disseminated on a fairly large scale via the countercultural press were Captain High by William Beckman and Fritz the Cat by Robert Crumb. Ultimately, in 1968, Manuel “Spain” Rodriguez created for EVO Trashman, a mystical terrorist living in a science fiction world of political anarchy. The EVO played a particular role in the promotion of this type of comic. Starting in 1969, it produced Gothic Blimp Works, a tabloid-sized comics insert. The brainchild of Vaughn Bodé, an illustrator coming from Cavalier who had suggested the idea to EVO’s business manager, this supplement was edited first by Bodé then by Kim Deitch. Although it only had eight installments Gothic Blimp Works left a lasting impression because all the big names of underground comics contributed to it.

An industry of underground comic magazines emerged in the second half of the decade after several false starts. This natural extension of the underground press was much smaller than the mainstream comics industry but comix became fixtures of the counterculture in head shops where they were sold next to psychedelic paraphernalia.

While student newspapers and the underground press network were the two forces that parented comix, Harvey Kurtzman’s Help! proved the commercial viability of illustrators who had been trained neither in syndicated cartooning nor in mainstream comic books. All that was missing was a publisher’s will to produce a new object radically different from newsstand comic magazines. There had been precursors—the first fanzines that appeared at the turn of the 1960s, in particular Wild, edited by Don Dohler and Mark Tarka in 1961 and 1962. This title published the first pages of Jay Lynch and two other budding illustrators who each produced their own fanzines, Skip Williamson (Squire) and Art Spiegelman (Blasé).10

In 1962 what has since been considered the first underground comic appeared. The Adventures of Jesus was a black-and-white fourteen-page booklet half the size of a mainstream comic book printed at the University of Texas–Austin. Drawn by Frank Stack (before he adopted the pseudonym of Foolbert Sturgeon) and published by Gilbert Shelton, at first without Stack’s knowledge, it included several tongue-in-cheek strips featuring Jesus Christ in parodic biblical settings or in contemporary America. This comic book went largely unnoticed upon its release: with a print run of a few hundred copies, most of which were given away to friends, it came across at best as a single-character fanzine. The off-the-wall format matched an off-the-wall subject matter as it were.

Stack’s Jesus was typical of the isolated and confidential nature of early underground comic publishing. In 1963 Vaughn Bodé, then a student at Syracuse University, also self-published a booklet titled Das Kämpf, whose hundred loose pages presented caustic drawings about the war. The following year, Gilbert Shelton’s second shot at comic publishing, Jaxon’s God-nose, was barely more remarkable than his previous attempt. In 1965, in Richmond, California, Sunbury Productions released two magazines written and drawn by Joel Beck, Lenny of Laredo! and Marchin’ Marvin. In 1966 The Great Society was a political satire comic in which writer D. J. Arneson and artist Tony Tallarico mocked the social reform agenda of the Johnson administration. In 1967, Zodiac Mindwarp, an all-comic supplement Spain Rodriguez inserted in EVO, proved a complete commercial failure.

The birthdate of comix was the February 1968 release of Zap Comix #1. The first run was printed by the beat poet Charles Plymell for Don Donahue under the Apex Novelties imprint and initially sold in the street by its creator Robert Crumb, his pregnant wife Dana, and Donahue.11 This comic was published in the right place, the heart of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood, and at the right time, in the wake of the “Summer of Love,” the nine-month-long celebration of hippie culture that took place in San Francisco in 1967. Thanks to the visibility acquired by the countercultural press the Berkeley Barb’s circulation then shot from five thousand to twenty thousand copies.12 Robert Crumb’s comic book mingled unquestionably original graphics with an incisive and nondidactic outlook that reflected the era’s rebellious mind-set. Beginning with the second issue, Crumb opened Zap to other artists: Rick Griffin and Victor Moscoso worked surrealist visuals into largely meaningless strips that echoed the psychedelic experiences of the beatnik and hippie generations. S. Clay Wilson launched a style of visual obscenity in his short stories that featured scatology, violence, and sexual perversions.

Zap Comix launched a movement that spread rapidly across the United States. Several long-lasting underground titles appeared in 1968: Yellow Dog (published by Print Mint in Berkeley), Bijou Funnies (published by Jay Lynch and Skip Williamson in Chicago in the wake of the defunct hippie magazine The Chicago Mirror before being taken up by Print Mint with the second issue).13 Gilbert Shelton self-published the one-shot Feds ‘n’ Heads Comics in 1968 and created the Freak Brothers. Little by little underground comics became profitable although not to the same extent as mainstream comics. The self-publishing that had defined the early 1960s was gradually replaced by an embryonic industry. Besides two publisher-printers-distributors—Print Mint, a poster business founded by Don Schenker in Berkeley in 1965 that focused on publishing as of April 1966, and Rip Off Press, the artist-run cooperative founded by Gilbert Shelton in San Francisco in 1969—other publishers appeared: Apex Novelties (founded by Don Donahue in San Francisco in 1968), Last Gasp Eco-Funnies (founded by Ron Turner in 1970), and Kitchen Sink Enterprises (founded in 1970 by Denis Kitchen in Milwaukee, Wisconsin), which was soon renamed Krupp Comics Works.14

Alternative comic publishing began thriving in 1969 thanks to the head shops. In an era when specialty comic book stores were practically nonexistent and mainstream distribution channels were closed to underground magazines because of their low print runs and often graphic contents, comix embodied a logic of marginality that assured their success at least as long as the countercultural movement lasted. In this regard the publication in 1969 of Radical America Komiks, a special all-comics issue of Radical America, the official review of SDS (“Students for a Democratic Society,” the federation of student protest groups issued from the Declaration of Port Huron in 1962), may be regarded in retrospect as a consecration of the comix medium itself. Underground comic books in their majority mirrored the synergy between the New Left ideology and the hippie movement. Most creators belonged to the hippie movement or were at least proximate to it (like Crumb); at the same time, they propagated an antiestablishment ideology in which many supporters of the New Left recognized themselves. Finally, on a more general level, the exuberant creativity of underground comics laid the groundwork for a future renewal of the mainstream comic book.

Until the 1960s the few auteurs found among cartoonists were a handful of syndicated artists. The three most renowned comic strip artists of the decade were probably Al Capp (Li’l Abner), Walt Kelly (Pogo), and Charles Schulz (Peanuts). Conversely no one knew the name of Carl Barks, the talented writer-artist who produced a large number of stories featuring Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge from 1943 to 1966, even when the magazines that contained his drawings were already sought-after collectibles. There was a hiatus in the public’s perceptions of the daily comic strip, the creation of an author designed for entertainment, and the comic book, a product that traditionally concealed individual creators.

The gap started to narrow during the 1960s. DC, and then Marvel, took the habit of systematically listing at the start of each story the names of the writer and artist. This practice was once common with early comic book publishers but had largely disappeared during the 1940s. Thus the only way to identify the author of a story was the signature of the artist, when it was legible; one of the reasons why Carl Barks and the other Disney illustrators (like Al Taliaferro or Floyd Gottfredson) remained anonymous for so long was that their strips were always signed “Walt Disney,” even though the great animator never drew a single panel of the several thousand strips published under his name. The interest in comic artists’ identities coincided with the coming-of-age of a generation that used to read postwar, pre–Comics Code comic books and were often familiar with the biographical sketches of EC illustrators (William Gaines invented the comic book star system by running biographical resumés and photographs of his artists in the pages of his magazines). The same individuals had developed a considerable interest in the history and inner workings of the comic book as an autonomous medium. For underground artists, comics was not a job but rather their chosen medium for self-expression: most of them shared the same passion for prewar humor comic strips (Rube Goldberg, Milt Gross, E. C. Segar, Cliff Sterrett, George Herriman, for example), and among comic books, for funny animals and children’s series such as John Stanley’s Little Lulu. By contrast the illustrators who chose to express themselves in mainstream comic books practiced more “realistic” graphics of superhero, romance, detective, and science fiction comics, work that Roy Lichentenstein pastiched in his canvases. Both underground and mainstream comic book artists, however, agreed in their admiration of the EC pamphlets and cartoonists, many of whom were still very active in the 1960s (Jack Davis, Joe Orlando, Wallace Wood).

Thus a process of individuation and of creative personalization started to alter the logic of undifferentiated production that had always structured the production of comic books. The industry, which had originally taken off thanks to a market segmented by genres, went through an evolution that gave pride of place to creators: the genre-driven industry became more and more creator-driven. Undergrounds showed the way in this regard: despite irregular publishing schedules and faulty distribution, comix functioned as fora for identifiable creators, whose appeal lay in their strong individualism. While mainstream publishers still strove to make readers faithful to characters rather than creators, underground comics promoted both genres and auteurs—a given pamphlet might sell as much for its contents as because it contained drawings by Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, Art Spiegelman, Trina Robbins, or others.

A similar phenomenon took place in the mainstream industry roughly at the same time, at first in the artwork. As the comic magazines bound by the Comics Code could not take advantage of the same liberties as their underground counterparts their renewal first assumed the form of a graphic experimentation such as the medium had not experienced since Will Eisner quietly revolutionized storytelling in The Spirit in the late 1940s. Between the 1950s and 1960s there had been an undeniable overall improvement in the artwork of comic books (largely inaugurated by the talented illustrators who used to work for EC in its heyday). Still several young artists emerged who were to have a lasting influence on the visual aspect of comic books by laying down the foundation for a new graphic canon by the late 1960s.

The artist with the most lasting impact was Neal Adams. A newcomer at DC in 1967 at the age of twenty-six, he was immediately noticed for his exceptional sense of framing and page layout and the quasi-photographic realism of his artwork, a skill that he developed when he worked in advertising. In the stories featuring Deadman, a character he took over in Strange Adventures in 1968, and his work on Batman in The Brave and the Bold starting in 1969, Adams deployed a graphic virtuosity that comparatively emphasized the traditional, conventional, and ultimately old-fashioned artworks of the creators born between the First World War and the Great Depression that were still active at the time (such as Jack Kirby and Gene Colan at Marvel, Murphy Anderson and Gil Kane at DC). The importance of Neal Adams was paramount because his approach to the comics page was destined to leave a lasting imprint.

While Adams illuminated the last few years of the decade, one shooting star produced similarly striking material. A former stage magician, acrobat, motorcyclist, and advertising artist, James Steranko began working for Marvel in 1966 and quit the comic book scene in 1969. Over a short period of time he instilled into the adventures of Captain America a baroque ambience based on distorted perspectives and creative uses of light sources. His most influential work was his stint on Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., a title featuring a high-tech super-secret agent that allowed Steranko to give in to his own penchant for splash pages teeming with individuals dwarfed by gigantic computers.

The third successful newcomer of the period was an “old-timer.” John Buscema began his career at Dell in the 1940s and worked for Marvel in the 1950s before turning to advertising after the mid-1950s slump. In 1966 Buscema returned to Marvel at Stan Lee’s invitation to draw The Avengers. By then his artwork, honed by several years outside of comics, looked remarkably supple and fluid. This brought Stan Lee to ask him to handle the pages of The Silver Surfer, an experimental giant twenty-five-cent bimonthly title featuring an unorthodox cosmic character with admittedly heavy-handed messianic overtones introduced in Fantastic Four in 1965. This comic book painfully epitomized the gap that had widened among comic book readers over the decade: while the children who still formed the majority of the readership balked at buying a magazine costing twice as much as a regular comic, the adventures of this lonely character tortured by nagging metaphysical doubts struck a chord with the college-aged audience during its short, eighteen-issue career. Mixing an unusually “literary” inspiration with very effective framing and layouts, The Silver Surfer was a unique creative achievement that Marvel has never been able to replicate. It was nevertheless a commercial failure that seemed to show that any ambition to radically break with mainstream products was doomed to failure.15

At the end of the 1960s comic books experienced the first signs of the identity crisis that they have since endured without interruption. Its main symptoms were the coexistence of mainstream and underground titles, the contradictions between innovation and market imperatives, the incipient exhaustion of superheroic narratives after less than a decade, the decline of DC, the rise of Marvel, the renewal of creators, and the latter’s introduction of new graphics breaking with the 1950s design without being necessarily well-received by readers. In all respects, the “comic book” then appeared as a cultural object whose future directions seemed still impossible to define after thirty years of symbiosis with the ideology of the American middle class. The rise of the underground sector by contrast emphasized the growing discrepancy of mainstream comic books with a society experiencing accelerated change.