Publishers have always been more interested in selling copies of their publications than in advancing the status of comics as an art form. It is this commercial concern that made comic books a pillar of the mass periodical industry in North America until the start of the 1960s. Distributed at the start of the 1930s wherever periodicals were sold, comics magazines benefited from a large-scale visibility that was the source of its initial success and its subsequent failure.

Among North American print periodicals, comic books had a particular status: their survival depended to a much greater degree on their sales than on their advertising receipts. The big magazines of the first half of the twentieth century, such as Saturday Evening Post, Colliers, and Harper’s Bazaar, derived the majority of their revenue from paid advertisements; thus, they were able to maintain low retail prices, because of the fact that advertising occupied more space than the writing in each issue. These magazines entered into a downward phase after the Second World War, when new types of magazines (like TV Guide and Playboy) attracted the attention of advertisers, to the detriment of general interest magazines whose sales remained stable. At the same time, the advertisements placed in comic books provide an essential element for understanding the evolution of comic book readership, at least from the point of view of the publishers.

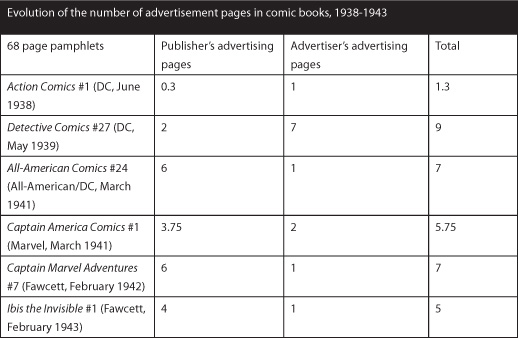

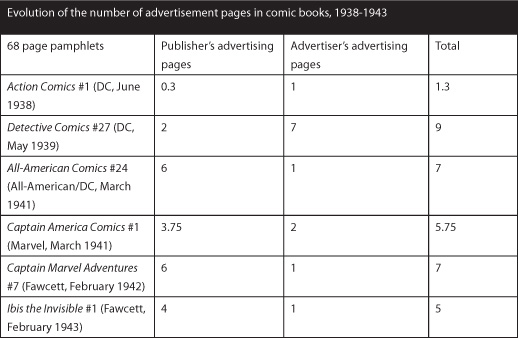

From the beginning, comic books carried little advertising. In the spring of 1938, Action Comics #1 had as its only advertising content a headline occupying the bottom third of page 13 promoting Superman and one page of ads for gadgets on the back cover. In the following year, Detective Comics #27 offered seven pages of diverse advertisements. Of the sixty-eight pages (including the cover) that made up the first comic books, this proportion of advertisements to content (close to a tenth) remained more or less constant, in contrast to the periodical norm in which half (if not more) of the available space was commonly occupied by advertising. During the war, as demonstrated by the examples between 1941 and 1943 in the table above, advertising for publishers’ other titles began to rise, partly because the lines filled out rapidly, and partly because the wartime economy had placed a halt on the offer of new consumer goods.

In the earliest comic books, advertisements were similar to those published in the pulps: gadgets (novelties), muscle development manuals, and stamp collections. It was at the start of the war, when the juvenile audience took on a new importance in the eyes of the publishers, that ads for candies, nonalcoholic drinks, and breakfast cereals first began to appear. In the meantime, dietary companies that manufactured products geared at youth directed themselves toward the all-ages comics of Fawcett and DC rather than to those of Fiction House or Marvel, which were more likely to contain sex and violence.1 After the war, the emergence of titles aimed at a female audience led to the introduction of ads for beauty products, clothes, and seduction manuals into comic books. In parallel, the growth of comic books aimed at a clientele of adolescents and young adults (such as the crime and horror comics) led to an equivalent expansion of advertising for various products that were seemingly irresistible to their users (including a tie on which was written, in glow-in-the-dark letters, the phrase “Will you kiss me in the dark, baby?”) and muscle manuals. The latter were omnipresent in comics until the end of the 1970s, at which point they became an inevitably parodic element of comic books. At the beginning of the 1950s, certain comics even published scandalous ads for “sex education” products that were similar to those distributed in the exploitation magazines that peddled the salacious gossip about the daily lives of stars. The implementation of the Comics Code placed some order on these excesses by imposing restrictions on the type of advertising that could be printed in comic books.2 Beginning in the second half of the 1950s, comic books reduced their page count from forty-eight (or fifty-four) pages to thirty-six pages, in order to maintain their cover price of ten cents. The number of advertising pages increased slightly but their proportion was growing. It was during the 1970s that the number of advertising pages reached its zenith, climbing to fifteen pages at Marvel and oscillating between eleven and sixteen pages at DC.3 In the 1980s the market stabilized, with a tendency to promote in-house comic book by-products, notably video games, animated cartoons, and role-playing games.

At the end of the 1950s ads were divided into two general categories: first, there were toys, gadgets, and trinkets that one could obtain through the mail from greeting card companies;4 second, there were correspondence courses (learning how to draw, learning a trade, finishing high school at home, muscle development, or karate lessons). The audiences being targeted by advertisers were, on the one hand, preadolescents that were being targeted as consumers, or urged to nurture their familiarity with a comic by learning how to draw; on the other hand, there were also adolescents that had left school or that lacked adequate professional training. The persistence of this genre of advertising through the 1970s speaks volumes on the probable sociological composition of the readership of this period. Comic books seemed to be the reading material of children generally, and of adolescents and young adults from disadvantaged sociocultural and socio-professional environments specifically. These types of ads continued to appear up until the 1990s. Later, they no longer took up entire pages, only appearing in small rectangles within a larger page of ads.

The mid-1960s saw the gradual appearance of a new type of advertisement which took the form of announcements of the sale of new and older comic books by correspondence. The first of this genre was found in Marvel comics dated July 1966. Four years before Robert Overstreet, a bookstore in Hollywood, Argosy Books, offered a price guide to secondhand collector’s comics. In less than a year, these advertisements invaded the spaces that were previously occupied by ads for coins, stamps, and rock collections. The population of collectors, until then restricted to the small world of fanzines, exploded once the general population of comic book readers discovered the existence of dealers who offered old comics for sale, and further learned that there was money to be made within this niche.5 In submitting themselves to this “nostalgia” market, these young readers developed their own interest in contemporary comic books. The multiplication of these kinds of ads in the second half of the 1960s contributed to the creation of a large clientele that would develop the structured network of specialty comic book stores. By means of these small advertisements, whose size was inversely proportional to the quantity of treasures that they promised, comic books of the 1960s “invented” the actual comics buyer, the collector-speculator.

Since the 1980s, comic books have published institutional and semi-institutional advertisements: among others, there were campaigns for medical research, science education, the consumption of milk (the campaign around the slogan “Got Milk?” was offered in a variety of forms featuring various superheroes beginning in the middle of the 1990s); there were also campaigns against illiteracy and smoking addiction. The publishers polished their image by acting in the interests of the community. Nevertheless, the advertisements published in actual comic books were, for the most part, limited to seven domains:

1. the promotion of collecting and speculation about comic books (addresses of comic book stores, convention announcements, special offers from dealers);

2. confectionary and candies (Oreo Cookies, Reese’s Pieces, Hostess Fruit Pies,6 and such);

3. video games;

4. role-playing games (e.g., Dungeons and Dragons);

5. action films and television series (with a tendency toward horror and science fiction);

6. rock music (concert announcements and new releases);

7. institutional advertisements.

Advertisement for toys, models, and hygienic products for adolescents appeared in a more sporadic fashion.7 In practical terms, the target audience for the publishers consisted of young adults up to their thirties. At the end of the 1980s, DC sought ads for cars, cameras, and computers for its titles, hoping that would attract readers between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four. This attempt failed because the comic book medium connoted too young an audience in the eyes of advertisers for potential consumers of these types of product.8

The advertisements appearing in today’s comic books present a wide range of references: video games based on role-playing games, featuring characters from comics and popular film; ads for popular films are side by side with those for rock music; the heroic fantasy and science-fiction-based imagery of video games relies on a design sensibility that is difficult to distinguish from film posters or ads for comic books. Until the 1960s, advertisements inserted into comic books testified to the socialization of readers into a larger sense of consumption. Beginning in the 1970s, where ads for television programs and blockbuster films multiplied within the pages of comics, the function of advertising itself evolved toward the global promotion of the culture industry in which comic books inscribed themselves as purveyors of concepts destined for other media.

When comic books first appeared in the 1930s, the mass periodical press was already well established and structured. Therefore it was necessary to understand and adapt to the existing methods of distribution. The introduction of comic books took place in an unstructured manner. Wholesalers that distributed new magazines had a habit of spreading them randomly among their clients (buckshooting). The first retailers to receive comic books did not really know where to place them on their shelves, since they were larger than the “Big Little Books” but smaller than the pulps.

The rationalization of comic book distribution was the result of a development in which the distributors were also publishers. In 1932, Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz founded the Independent News Co., a newspaper distribution company that, starting in 1935, circulated the comics of National Allied Publishing. When they became the owners of DC in 1937, Donenfeld began releasing comic books originating from the New York region, establishing distribution channels close to other distributors. As both publisher and distributor, he contributed to the entry of comic books into the routines of wholesalers and opened their doors to the other publishers that appeared in the wake of DC. The second stage of this rationalization emerged at the end of the 1930s, when the demand for comic books began to increase. While wholesalers practiced the distribution of their periodicals in a logical fashion, there was an increasing rationalization of distribution at the retailer end. One of the first to take this step was the Delmar News Agency of Wilmington, Delaware. At the end of the decade, its owner Erwin M. “Bud” Budner approached Donenfeld and Liebowitz to optimize comic book distribution by modulating the orders and deliveries as a function of the sales achieved by particular retailers. Much like Donenfeld, Budner was interested in multiplying the number of points of sale.9

Once these foundations were laid at the start of the 1940s, the system essentially remained the same until the 1970s. A publisher sent the original pages of their comics to an engraver; the plates were transmitted to a printer who printed and bound the comics (most often they were stapled). They were then sent to the distributor with whom the publisher had a contract and who was sometimes a branch of the same company. Of the thirteen active distributors in the comic book industry of 1954, there existed no less than seven publisher-distributors (Ace, Atlas [Marvel], Capital [Charlton], Fawcett, Gilberton, Independent News [DC], George A. Pflaum).10 The distributor would ship the comics to its regional clients (independent distributors) who served as wholesalers. There were around seven hundred of these in 1952. These independent distributors provided comics to retailers, not only newsstands but also grocery stores, pharmacies, and other neighborhood stores (variously known as corner stores, convenience stores, five-and-ten-cent stores, mom-and-pop stores), as well as roadside bus and railway stations, where numerous books and magazines of all types were sold to travelers. In 1952, there were approximately one hundred thousand press retailers in the United States.11

This system assured the distribution of comic books to the farthest regions of the United States and Canada. At the same time, it experienced successive dysfunctions for reasons that were initially economic, then sociological. The first dysfunction was known as tie-in sales. Certain wholesalers would not deliver the most popular magazines (such as TV Guide) to retailers unless they also took titles that were less profitable or “morally contestable,” such as certain comic books, erotic magazines, and other scandalous magazines (exploitation magazines). This practice, which was standard until the mid-1950s, was vigorously denounced by retailers on the occasion of their audience at the senatorial subcommission on juvenile delinquency on June 4, 1954.12 The other weakness of the traditional distribution system arose in the 1960s. It was linked to the demise of small shopkeepers that were prominent in North America before they were phased out by the rise of supermarkets. With the erosion of rural retailing, of small towns, and their accompanying lifestyle, the reduction in the number of these types of retail outlets in thirty years contributed to the declining revenue in the comic book industry. The supermarkets that took the place of these small businesses were often reluctant to sell comics whose profit margin was negligible for them. Additionally, they feared that young buyers would, as they did in the mom-and-pop stores at the time, stand around for hours reading the magazines before buying them, which was counter to the principles of rapid client rotation that drove these large spaces.

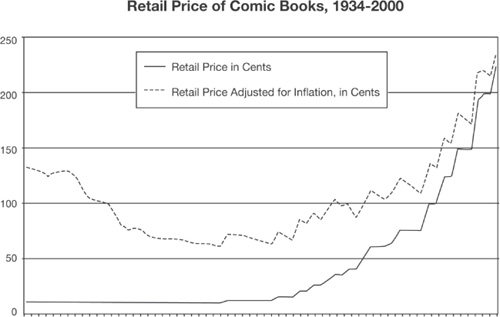

Beginning in the second half of the 1960s, comic books entered into a transitional phase that was closely linked to the evolution of American society. With the disappearance of small retail businesses, comic books were less omnipresent, less easy to procure, and above all, more and more costly (see graph). Compared to the evolution of the cost of living, the successive increases in base price (that is, the lowest sales price offered by the large publishers in a given period) to fifteen cents (1969), twenty cents (1972), twenty-five cents (1974), thirty cents (1976), thirty-five cents (1977), forty cents (1979), fifty cents (1981), one dollar in 1990 (the year where comic books had the same value in inflation-adjusted dollars as they did when they debuted in 1934), and over two dollars in 2000, made comic books the most expensive of periodicals relative to the free time that they occupied.

At the turn of the 1970s, the traditional distribution system was no longer adapted to the reality of the market. The neighborhood stores that had historically served as the principal retailers of comic books were suffering an inexorable retreat. Then, thanks to the weak profit margin for these magazines, more and more wholesalers and retailers deemed them of little value, feeling that it was more advantageous to leave them in their wrapping, not even putting them on the shelves since they would occupy a place where other, more potentially profitable periodicals would sit. Finally, the system of affidavit returns, which encouraged fraud at the level of local distribution, contributed a new dysfunction. Over the course of the 1960s, in order to save money, the large publishers stopped asking distributors and wholesalers to send back the covers of their unsold comics as a way of calculating what was owed. What was put in its place was a simpler operation in which wholesalers “honorably” declared, without having to supply proof, how many copies were sold to retail businesses and how many copies were returned to be pulped. In the absence of controls, it was easy for the black market to resell millions of copies that were officially listed as destroyed and to invoice their worth as future credit with the publishers. The result of this fraud was that, in 1974, as little as a quarter of all printed comic books were physically placed for sale at retailers. Publisher James Warren has spoken about recovering dozens of copies of his magazines that never left the warehouse because, for certain wholesalers, transporting them to retailers and recovering unsold copies was, in the end, more costly than not even opening the package that could then be reclaimed as credit.13 When clandestine resale took place, it was done to the benefit of specialized bookstores or of collector-merchants in a scheme that could, in a given region, generate shortages of certain popular titles. These practices continued through the 1970s, until the adoption of the direct market distribution system, which rendered this form of fraud obsolete, because sales to specialized bookstores were made on a nonreturnable basis. Beginning in the 1980s, the growth of the comic book store noticeably affected comic book sales at newsstands and neighborhood stores. By this point traditional distribution represented no more than 15 percent of the industry’s business.

From the 1960s, comic books distributed by press distributors depended on a system supervised by the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA). Since the time when newsstand distribution reigned, the CMAA diversified its activity by enacting a color-striping system that appeared on the top edge of comics indicating to retailers when to return unsold copies to wholesalers. Given a sequence of colors (red-purple-green-blue-black), the delivery of new comics carrying a red band signaled to retailers the return of older comics with a black band, while the subsequent arrival of the purple bands signaled the return of the red bands, and so on. This system was used exclusively for the comics published by the subscribers of the CMAA.

Though the direct market distribution system represented the overwhelming majority of sales for Marvel and DC beginning in the 1980s, the two leaders never completely interrupted the distribution of their titles in neighborhood stores as the loss of visibility was too potentially damaging. Besides, the large publishers had found the means to make newsstand distribution a complement to the collector’s market. In the 1980s and 1990s, it was common to see different versions of an issue produced for the two sales networks (for example, this was the case of the first issue of the Man of Steel limited series released in June 1986, in which John Byrne inaugurated the modernization of the Superman character, and also Amazing Spider-Man Annual #21, published in June 1987, which depicted the marriage of Peter Parker/Spider-Man). The diehard collector or speculator would feel “obliged” to procure several copies of the version that was not found in specialized comic book stores.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, the contraction of the traditional distribution system seemed inexorable. In May 2001, founding member Marvel quit the CMAA. At this time, the last member publishers were DC, Archie, and Dark Horse (the only independent publisher that risked newsstand sales in the 1990s). Marvel’s reasons for leaving were largely economic. Between 1998 and 2000, its sales in the direct market distribution exceeded 90 percent. If, as is likely, the division of revenue between the two systems of distribution was analogous for DC, since 2000 traditional distribution represented less than 10 percent of the industry sales, against 15 percent in 1992.14 The phenomenon could be similarly found among other publishing houses. Between 1990 and 2000, the hundred best-selling magazine titles saw their sales at newsstands drop 40 percent. Having occupied a marginal position for so long with respect to the periodical press, comic books were also stung by the decline of newsstand sales—even Archie sold fewer copies of their comics in this network that represented over 90 percent of their sales! On the other hand, the comics buying audience gradually started with contact with graphic novels and became less familiar with comics in their pamphlet form. Thus, a tremendous mutation that began in the 1970s largely eliminated the presence of comics pamphlets on the newsstands where they had prospered since the mid-1930s progressively driving comics toward its new status as a book medium detached from the economic and cultural universe of the periodical press.

After ending his career as a high school teacher, Phil Seuling became well known as an organizer of conventions for fans and collectors at the end of the 1960s, and for opening one of the first comic book specialty stores in Brooklyn in 1969. From the start Seuling was conscious of the inadequacies of the traditional distribution system which was unable adapt to a specialized business such as his. From this realization came the idea for a system in which publishers sold their comics directly to bookstores, without passing through the hands of intermediaries (distributors and wholesalers) for whom comic books were little more than an unprofitable sideline. In 1973, Seuling proposed this new system to the large publishers, which would allow them to avoid the primary pitfall of the traditional circuit—the return of unsold units. Publishers had always been obliged to print copies without knowing with any certainty how many copies would sell, or even if an issue that was particularly popular would require reprinting. Once the period during which comics were on the shelves had passed, retailers returned them in exchange for credit on future orders. This system obliged publishers to print a greater number of copies than they knew they could sell. The first comic book specialty stores benefited from both the advantages of this system and especially its inconveniences (such as the difficulty of adjusting the volume of orders), while the distributor, acting as an intermediary, did not assume any risks.

Seuling’s idea was revolutionary because it reorganized the distribution of comic books by saving money for publishers and bookstores. He asked DC to sell their comics to him at a lower price, which allowed him to pass along the savings to the bookstores. At the same time, the bookstores determined their orders based on sales three months in advance of a comic’s release. In the process they gave up the possibility of returning unsold comics to the publishers. In this system, publishers were paid immediately by the distributor and could establish their print runs based on existing orders, no longer having to worry about returns. At the same time, retailers were able to rationalize their business and manage the stock of their back issues.

In November 1973, DC adopted the direct sales system advocated by Seuling; Marvel did the same in December. For several years, it remained a secondary outlet for the Big Two, despite a regular increase in sales volume at specialized bookstores beginning in 1974 (for example, Marvel titles distributed by this network generated revenues of 300,000 dollars in 1974, 1.5 million in 1976, and 3.5 million in 1979).15 While publishers saw their profits drop globally over the 1970s (as seen in the regular increase on the cover price of comic books), comic book stores experienced growing prosperity.

It was only at the end of 1980 that Marvel developed products exclusively destined for the direct market. One year later, Marvel undertook an internal assessment of their operations and the financial health of the comic book stores in the country and, during a meeting organized in August 1979 at the San Diego Comic Convention, invited Chuck Rozanski, owner of the Mile High Comics chain of bookstores in Boulder, Colorado, to present the perspective of specialized retailers.16 In the fall of 1980, when the sales of X-Men in direct distribution broke the hundred-thousand-copy bar, Marvel announced that the first issue of its new title Dazzler (starring a disco super-heroine) would be available only in specialized bookstores. The result was convincing: with more than four hundred thousand preordered copies, this comic more than doubled the average sales volume for a Marvel title of that era. The success of this experience proved that a skillful promotion directed at the clientele of comic book stores could have considerable commercial potential. Four months later, DC attempted an analogous experiment with Madame Xanadu, a one-shot that sold a hundred thousand copies, a strong result for a DC comic.

The first consequence of these developments was that, at the instigation of Mike Friedrich, the head of sales to comic book stores, Marvel decided to distribute one of its series exclusively in this channel. After a stunning launch in 1978, the sales of The Micronauts, a series inspired by a line of science fiction toys, began to gradually shrink at the newsstands, while maintaining their levels at comic book stores. In May 1981, Marvel announced that starting with issue 38, The Micronauts would be available only through direct distribution: it would no longer contain advertisements and its cover price would increase from fifty cents to seventy-five cents. When the success of this approach was confirmed, Marvel decided to apply the same formula to Ka-Zar and Moon Knight, two titles whose sales patterns were analogous to those of The Micronauts. This was the birth of the first direct-sales titles, series that were reserved for the comic book store circuit. Their elevated cover price and their printing on high-quality paper targeted them to an urban and relatively upscale clientele—it was a far cry from the era where the purchase of comic books was made at corner stores while shopping for groceries. The impact of this innovation was considerable since it was founded on the confidence in a new type of commerce that offered comic books as distinct objects, rescued them from the indifference that was their lot on newsstand shelves, and assured the economic dominance of comic book stores, and above all, their continued growth. As the supply increased the volume of demand, a growing number of newcomers diversified a readership increasingly open to novelty and to the different comics produced by Marvel and DC.

At the level of distribution, Seuling initially wanted his company, Sea Gate, to maintain exclusivity in the direct sales market, but many of his larger clients found the new system to be so efficient that they signed similar contracts with the large publishers themselves. The second half of the 1970s saw the growth of direct sales distributors, who were often bookstores serving their counterparts in various regions. Nevertheless, the limited number of specialized bookstores at the time hindered the development of large distributors in the New York area, Sea Gate’s turf, and of California, which was Bud Plant’s fiefdom from 1972 to the end of the decade. Beginning in 1980, the multiplication of distributors continued as the large publishers opted to support this increasingly important market. In the United States, as well as Canada, several large bookstores launched their own distribution division to rationalize their supplies and to profit from the activities of their less financially stable competitors. This proliferation came to an end with the black-and-white comics glut of 1986–1987 which led to the closure of many comic bookstores and small distributors. In the years that followed, the aftereffects of this crisis, in the forms of failures, repurchases, and mergers, finally initiated a reorganization of direct distribution starting in 1988.

Until the crisis of 1994, this direct market was divided between two giants and a half-dozen smaller distributors. At the head of the line (as it is to this day) was Diamond Comic Distributors, whose head office was in Timonium, Maryland. In 1992, Diamond controlled half of the market with twenty-one distribution centers in the United States, two in Canada (in British Columbia and Alberta), and one in Great Britain. Its largest competitor was Capital City Distribution in Madison, Wisconsin, who controlled more than a third of the market at the time with nineteen distribution centers spread out across the United States.

The distributors not only served comic book stores but also the non-specialized neighborhood corner stores to whom they supplied comic books based on the traditional distribution system. Each month, they sent out a bulky magazine so that their clients could prepare their orders (Previews at Diamond, Advance Comics at Capital City). These catalogues contained information about the various items that would be available in three months’ time. These magazines contained information note only about comic books, but also about collector’s cards, science fiction books, videocassettes, role-playing games, and derivative objects related to all of these items. Retailers made their orders and sent them in, along with payment, to the publishers without any real assurance that the items ordered would be available on the announced date. Ultimately, the distributors had no control over the capacity of the publishers and manufacturers to have their items for sale on the given deadline. With respect to comic books, late shipping was a constant problem that proved to be fatal to many new bookstores and small publishers, especially during the crisis of the mid-1990s. These new businesses did not offer any specific services, such as sales by mail or a large back catalog of comic books and collector’s objects. In this regard, they differed markedly from the distributors at the beginning of the 1980s, who attempted to insert themselves into all levels of the market and in a maximum of niches.

As a market based primarily on a clientele defined by notably lunatic collector-speculators, direct market distribution as been the victim of faddish waves that have rendered its management uncertain. Following three small crises in the 1980s, The implosion from 1993 and 1996 had deleterious effects for all the players in the market. The recession stemmed the growth of a speculative bubble in which supply saturation made it impossible for buyers to absorb the overabundance of comics suddenly for sale. The three smaller recessions of the 1980s set the stage for this crisis at several levels:

1) The first crisis experienced by comic book stores was the mini-crash of September 1983. This was provoked by the competition between the Big Two publishers who, in seeking to inundate the market in a quest to maximize market shares, produced more titles than demand was capable of absorbing. Marvel represented 80 percent of the sales achieved through direct distribution at the time and DC represented 16 percent. The remaining 4 percent was spread among a number of small publishers. According to Robert Beerbohm, Marvel initiated a crisis that unfolded in two parts: first, after having weakened DC in the fall, Marvel offered bookstores the opportunity to preorder a wide variety of new series over the first few months of 1984, all of which were to be simultaneously released in September. The result of this strategy was that the majority of comic book stores, whom Marvel prioritized because their accounts represented 80 percent of its revenues, had to budget a colossal sum of money for that month and found themselves incapable of settling their bills with other publishers. For the small publishers, who had been weakened over the preceding year, this was a huge blow, which led to the failure of Pacific Comics.17

2) The second crisis was caused by the small publishers. In 1986, the unexpected success of the black-and-white comic book Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles18 (TMNT) in 1984–1985, and the ongoing success of series such as Cerebus created an artificial demand for black-and-white titles. Many speculators believed that the value of these comics would multiply a hundredfold, following the example of the first issue of TMNT. Retailers passed along this demand to distributors, who offered them an abundance of new titles that appeared seemingly overnight during 1986. This sudden influx was made possible by the ease of producing a black-and-white comic book at low cost. From 39 titles of this type available in January, the supply jumped to 170 in December, and at the same time, no less than 60 new small publishers appeared. The start of 1987 was a difficult time for many retailers who found themselves with large numbers of unsold, and unsellable, black-and-white comics, since few rivaled the success of Cerebus or TMNT. The fall was even more difficult as the expansion of titles was accompanied by a 10 percent to 15 percent growth in the number of comic book stores, a large number of which closed down in less than a year.19

This crisis had its roots, on the one hand, in a policy that was endorsed by distributors (who were the least financially exposed), who were ready to offer even the most slapdash comic for sale. On the other hand, the greed of retailers who sought to profit from an economy built on a tainted foundation, catered to speculator-buyers investing their capital in comics that could never be resold. The collapse in the spring of 1987 led distributors and retailers to realize that Cerebus and TMNT were successful thanks to their intrinsic qualities and not simply because they were in black-and-white.

3) A third crisis, of lesser importance, occurred in 1988 when publishers began releasing graphic novels in an uncontrolled fashion. The success of the trade paperback of the 1986 limited series Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, as well as the apparent profitability of the reprints of Cerebus, newly bound into large volumes available only by mail order, led Marvel to multiply the reprints of comic books that were successful at the time of their initial appearance. The small publishers followed the footsteps of the larger ones, and at the end of 1987, 140 graphic novels and trade paperbacks were solicited for the first semester of 1988. Of course, it was impossible for the average comics buyer to absorb all of this product.20 This time around, the crisis was not as severe for comic book stores. The books published by the large and midsize publishers sold well but the money that was set aside for them came at the expense of the smallest publishers, who, at the end of the day, were the only ones to suffer from this overabundance.

Having overcome the crisis of 1986–1987, the major players in the market seemed taken by the dream of the indefinite growth in the direct market. The number of comic book stores grew from around twenty-five hundred at the end of the 1980s to over nine thousand in 1993. The incredible success of the film Batman (Tim Burton, 1989) had boosted the system. Numerous new publishing houses began to appear: in 1990, Valiant (a label of the publisher Voyager Communications), Drawn & Quarterly, and Tundra; in 1991, Harris (the product of a large magazine publisher) and Cartoon Books; in 1992, London Night Studios, Entity Comics, Chaos! Comics, and Topps Comics. That year, the comic book industry constituted a market of seven hundred million dollars. Nonetheless, the following year, a brutal interruption of this growth provoked a recession in the industry whose effects would be felt well into the following decade. The crisis, whose first victims were the retailers, resulted from the effect of a shift in market focus from comic book stores to collector-speculators. It was amplified by the distributor wars that followed the attempt made by Marvel to unsettle direct distribution by trying to take control of it.21

In December 1991, seven of the most popular artists at the end of the 1980s, including Todd McFarlane, Rob Liefeld, and Jim Lee, left Marvel when their request for ownership rights on any future characters that they would create was turned down by president Terry Stewart. In February, they announced the creation of their own label, Image (cofounded with Marc Silvestri, Erik Larsen, Jim Valentino, Whilce Portacio, and initially distributed by the publisher Malibu). This development was reminiscent of Atlas/ Seaboard, whose attempt to compete against Marvel in 1975 lasted only a few months,22 and also of the repeated failure of independent publishers in the 1980s who specialized in superheroes (Pacific, Capital, Comico, and First), all of whom ended in failure due in part to market saturation strategies employed by the large publishers. The emergence of a third force that could challenge the Big Two, who had dominated the entire industry since the end of the 1960s, seemed highly improbable. But, in contrast to these earlier cases, Image launched a series of titles backed by the superstar popularity that their creators had achieved at Marvel. To the surprise of the Big Two, the first Image comics were instant commercial successes, with sales surpassing a million copies per issue (including reprints), and Image took away 15 percent of Marvel’s market share. In the spring of 1993, Image adopted the cooperative operations that remain unchanged today: the studios or the artists that they publish retain ownership of their creations and are free to publish elsewhere when they want to.

The spectacular sales numbers of the first Image comics were due not only to the popularity of their creators but also to two other factors. The first was the simultaneous emergence of new customers originating from the trading card market and moving into comic book stores. After the collapse of the speculative bubble that had carried it for several years, the trading card industry branched into comic books, which seemed to be an industry ripe for speculation. While numerous stores that had previously specialized in trading cards mutated into comic book stores, sales of comic books experienced greater growth than the actual increase in the number of new buyers. The second factor contributing to this artificial growth was the impact of Wizard magazine (created in 1991), which transformed readers into speculators by hammering them with the idea that the market for new comics was an untapped source of speculative profits. The end of the 1980s had witnessed the development of strategies aimed at increasing the number of copies of any single comic book sold to a single reader. The sale of multiple versions of a particular issue with different covers, embossed covers, holographic covers minted in aluminum, and copies sold in sealed bags containing “exclusive” supplements (including trading cards and posters). Anything was possible in an effort to sell more comic books! With the initial success of the Image titles, this tendency got carried away: the increase in sales drove competing publishers to increase their print runs and the number of their titles while comic book stores increased their preorders accordingly.

The first problems arose in the spring of 1993. After the speculation peak, which coincided with the national publicity barrage surrounding the “death” of Superman in November 1992 in Superman #75, sales numbers began to fall. Since the start of the Image boom, a vicious circle was being drawn where sales would increase though profits would drop, mainly because of the late shipping (initially over several weeks, then several months) of Image titles, which represented an enormous percentage of retail orders. Lateness was largely due to the media overexposure of the creators, which prevented them from holding to their production deadlines. In this industry where retailers placed firm nonreturnable orders three months in advance of the release of the products, the economic effects of lateness were disastrous for several hundred small bookstores already suffering from precarious management and under-capitalization. When the preordered comics would arrive in enormous quantities at the stores six months, nine months, or even a year later, they were no longer sought after and sold poorly, while the stores nevertheless had to settle their bills with the distributors. As the following issues had already been ordered before it became clear to retailers that they would all suffer from accumulated lateness, this scenario would repeat itself again and again, contributing to the failure of the most fragile bookstores, particularly the thousands of trading card merchants that had entered the comic book market without any particular knowledge of the specific mechanisms of the industry and who were already suffering from the collapse of the baseball trading card market resulting from that year’s Major League Baseball strike. As speculators abandoned comics, the volume of sales fell for more than two consecutive years until stabilizing at the beginning of 1995, having dragged down many small and midsize publishers in its wake.23

There was to be no respite. In March of that same year, Marvel announced that its titles would only be distributed through Heroes World, a small distributor purchased by Marvel in December 1994. The official reason for this new policy was to offer an alternative to the deficient operation of the industry over the course of the previous year. The repercussions were considerable. Without Marvel, Andromeda, the main Canadian distributor, closed shop in mid-April; the second largest American distributor, Capital City, launched an unfair competition lawsuit against Marvel and Heroes World, and at the end of April, against DC and Diamond, the largest distributor in the country, after those two companies announced the signing of an exclusive contract. Capital City and Friendly Frank’s (the third largest American distributor) attempted to sign exclusive distribution agreements with the remaining publishers, particularly the two primary independents, Image and Dark Horse. These two publishers announced in July 1995 that, like DC, they had signed with Diamond. Incapable of ensuring the same services as its rival, Capital City was purchased by Diamond in July 1996. At that time, they represented only 12 percent of the market (compared to 87 percent by Diamond). In February 1997, Diamond announced that it would take over the distribution of Marvel titles. Heroes World turned out to be an extremely mediocre distributor whose unreliability had accentuated Marvel’s precarious financial position, which had resulted in a filing for bankruptcy protection in December 1996.

For comic bookstores, the quick succession of the speculation crisis and the distributor wars had disastrous effects. Though the numbers vary considerably from one source to another, it is estimated that from a peak of around ninety-four hundred comic book stores in 1993, that number declined to six thousand in August 1995, then forty-five hundred one year later. In three years, over half the specialized retailers had closed shop. Several publishers appearing at the wrong moment had little chance to make their mark: Entity Comics (1992–1997), Topps Comics (1992–1998), Defiant (1993–1995), Broadway Comics (1995–1996), and Tekno Comix (1994–1997), among others. From an estimated 900 million dollars in 1994, in the following years the direct distribution industry lost two-thirds of its value. By 2003 it had only rebounded to an estimated value of 450 million dollars, of which 60 percent came from the sales of new comic books.24 Diamond occupied a quasi-monopolistic position from the second half of the 1990s, which made it the object of an inquiry by the Department of Justice from 1997 to 2000 for infractions of antitrust legislation. Marvel, whose ownership was the subject of a battle between several financiers from 1989 to 1998, did not really recover from this prolonged crisis until 2000, with renewed visibility that accompanied the success of the X-Men film.25 The crisis highlighted the fragility of the direct distribution system, which is always at the risk of market saturation that affects small retailers and publishers in the short term as they are less stable and were less suited to the shifts in demand away from magazines and toward books.26

There were approximately twenty-three hundred comic book stores in North America in 2002.27 There were less than twenty-five at the end of the 1960s and less than a hundred in the mid-1970s (independent of the head shops). There were probably less than one thousand at the start of the 1980s. In 1985, there were over three thousand stores whose combined turnover represented half the total sales of comic books in the United States, four thousand in 1987, and eight thousand in 1992. The rapid growth of specialty comic book stores in the 1980s was certainly influenced by the general revival of the American economy under the Reagan administration, but it was rooted in the rapid evolution of the products that they offered and the clients that bought them. From the 1940s to the 1970s, the principal audience for comic books fell in the age range of eight to twelve years, even if during the 1960s, comic books benefited from a certain visibility with students. In 1987, Buddy Saunders, president of the Lone Star Comics chain of comic book stores, estimated that his business depended on a clientele aged seventeen years and older. At the same time, a survey taken for Marvel revealed that the average age of its comic book readers was around twenty years old.28 The aging of comic book readers was normally accompanied by an increase in buying power. Publishers were prepared to profit, offering more expensive products and focusing interest on creators, so that more “sophisticated” stories could be produced, ones that would attract an audience of students or those entering into maturity. One long-term consequence of this tendency was the permanent increase in the average price of comics, which accentuated the retreat of comics books from newsstand sales.

At the same time, while comic book stores constituted an exceptional example of adaptation to demand, this was largely because their business was not limited solely to comic books. In its section dedicated to comic book stores, the 2004 Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide indicated no fewer than thirty categories of items that these stores were likely to offer, aside from new, old, and underground comic books. Books, magazines, old paperbacks, pulps, “Big Little Books,” movie posters and stills, original pages, old and modern toys based on comics and animated cartoons, old records, trading cards, videocassettes, posters, comics supplies (primarily plastic bags, thick Bristol boards, and cardboard boxes allowing for the secure storage of a comic book collection), role-playing games, Star Trek items, and items related to Japanese animated cartoons were commonly found in comic book stores. In practice, this list can also include a growing array of clothes (such as T-shirts and caps), video games, and (very expensive) statues of popular characters.

Though this assortment appears heterogeneous, the items that compose this list strongly correspond to the various types of leisure activity appropriate to adolescents and young adults (up to thirty-five years of age) in North America. Books in comic book stores are usually fantasy or science fiction novels, or works that were based on comics, cinema, television, and characters from these genres. Although few customers are potential consumers for all or most of the categories of objects offered in these stores, it seemed natural that baseball cards were found near comic books, works of science fiction, and film magazines. Since the end of the 1980s, video games and all their related items, as well as Japanese comics and videocassettes, had made inroads into these stores. This is a far cry from the simple comic book stores of the 1960s. In fact, in the overwhelming majority of actual comic book stores, comic books rarely represent the majority of the sales turnover. The other items constitute important sources of income, to the extent that they attract clients coming in to purchase a certain object and leaving with another. Certain very specialized items, such as costly pages of original art that attract several atypical connoisseurs, function as markers of prestige.

Despite the variety of items for sale in comic book stores, a large number of clients frequent the establishments primarily to buy comic books, which have always been afforded a space of privileged visibility. To this end, at the end of the 1980s, publishers, in collaboration with distributors, put into place a certain number of strategies aimed at enhancing the synergy between comic book stores and publishers in order to rebuild the audience that comics had lost since the beginning of the 1950s. The speculation frenzy that had rebuilt the comic book market in the 1980s was intensified by a number of processes that professionals call “sales enhancement.” These practices rested on the near certainty that the speculator-collectors who constituted the hard core comic book store clientele reacted in a manner that was predictable, immediate, and entirely irrational, when the possibility existed that a comic would become a collectible object that could later be resold for a profit.

Sales enhancement consisted of attaching a particular exterior to a given comic book in order to distinguish it from other comics that were published at the same time. The ancestor of this strategy was the dual cover: an issue of a comic book series would be released with a certain cover in the traditional market and another cover for the comic book store. The first example of this procedure dates from the fall of 1989. In the wake of the success of the film Batman, DC published Legends of the Dark Knight #1 (November 1989) under a dual cardboard cover offered in four different colors. Speculators bought the same issue four times, in fear that fewer copies of one or more of these covers were printed. That week was one of the rare occasions in which DC sold more comics than Marvel. For the first time, a publisher exploited the irrational comportment of speculators to artificially boost sales.

The idea subsequently experienced a significant expansion. Identical multiple covers for a single issue were succeeded by different multiple covers. Furthermore, covers in bas-relief, silver, gold, and holograms also flourished. Comics were sold in sealed plastic bags (polybags) that contained diverse enhancements such as posters, cardboard assemblies, and of course, trading cards. For example, Batman: Shadow of the Bat #1 (June 1992) was sold in a plastic bag sealed with a black strip announcing Collector’s Set—in addition to the comic it contained a 3-D pop-up and a map of Arkham Asylum, two color posters, and a bookmark reserved for this edition. To these strategies were added others that had become proven formulas over several decades: the addition of a particularly popular artist, the appearance of a popular character, like Wolverine at Marvel or Batman at DC, in the adventures of another protagonist (crossover), or the development of a single story over several parallel series (tie-in) in order to oblige the reader to buy titles other than the ones that they were regularly reading. All these techniques functioned and continue to function, though to a lesser degree, as a way to sell isolated issues or series of limited quality to a small subset of fans. The sales enhancement devices (or gimmicks, as their detractors termed them) generated considerable profits for the direct sales system, representing an indefinitely renewable stream of exceptional sales. It is largely thanks to these artifices that the volume of the comic book market grew from 300 million dollars in 1988 to 400 million in 1990, 500 million in 1991, and 600 million in 1992. At no time in the postwar era had the comic book industry experienced such growth. The crash in 1994 was even more breathtaking because it had been amplified by the intersection of the crisis in the trading card market.

In the United States since the end of the nineteenth century, trading cards constituted a central component of North American popular culture because of their organic links to collective competitive sports and the transgenerational practices that organize themselves around them, so that the hobby was likely to incorporate parents as well as children. Trading cards were originally photographs of baseball and football players with a short biography printed on their backside that were inserted inside of cigarette packs, then, in the 1930s, chewing gum. Today they are sold in a sealed opaque plastic wrapper. To assemble the teams performing in these sports year after year, it was necessary to purchase several packs and to exchange cards in double (or triple or quadruple or more) with other collectors. Series assembled in this way acquired a variable value on the collector’s market, where cards depicting stars could attain astronomical values according to their condition. Trading cards constituted a much older market than comics. Unlike comic books, whose revenue came from a hard core of young adults between eighteen and thirty-five years of age, the audience for trading cards consisted of all age ranges and all social milieus because they took their content from sports, which constituted one of the only cultural domains that transcend class difference in North America. In 1992, before the crisis in the mid-1990s, the trading card market represented between 1 and 1.2 billion dollars,29 which was practically double that of comic books.

It took a long time for trading cards to become aligned with the comic book universe. Manufacturers believed that they could not interest card collectors in subjects other than sports. If we except a Superman series produced in 1940 by Gum, Inc., the first cards inspired by comic book characters were those published by Topps in 1966 in support of the television programs starring Superman and Batman. A small number of series appeared in a sporadic manner starting at the end of the 1970s based on the Superman films (1978–1983), the television series Hulk (1979), and the films Supergirl (1983) and Howard the Duck (1986). The first series published without a link to a film or a television program was the ninety-card Marvel Universe series offered by Comic Images in 1987. It was in 1990 that Impel published the series Marvel Universe I that appealed to collectors with deluxe production values and a clever visual style aimed at collectors. The set also had bonus cards with a smaller print run than the cards that formed the base of the series. Over two years, Marvel seemed to be the sole beneficiary of this new product until DC experienced a success with the Death of Superman card series published by Skybox at the end of 1992.30 At the same time, there was a growth at Marvel of comic books in sealed plastic bags, each containing a card taken from various series offered by the publishers. DC followed the movement in 1991. In 1992, with close to seventy manufacturers, three card publishing houses handled almost half the market—Skybox, Topps, and Comic Images (the only house that did not publish sports cards, and so its ascension in two years was dazzling in this particular context).

For the comic book publishers, creating a place in the market for trading cards had a dual purpose: to attract some of the money that a number of their customers, collector-speculators among them, already spent on cards in addition to what they spent on comic books; but also to lure customers interested in comic books to the collecting of cards. Nonetheless, to be a card collector meant entering an economic circle from which it was hard to leave with a winning hand: the cards are sold in sealed packs where they are randomly inserted in tens; a series of one hundred cards necessitated the purchase of a minimum of ten packs in order to assemble a set since double copies and missing cards would be inevitable. Added to this equation is the uncertain presence in the packs of a small number of “limited printing” supplementary cards—signed by the artist or containing a holographic illustration—which multiplies the sales possibilities. That certain unscrupulous merchants were able to open and reseal the packs containing the special cards (holographic cards were sensitive to metal detectors) in order to sell the cards individually speaks to the level of commercialism that motivated publishers, distributors, and retailers to favor the intermingling of these once distinct industries. Already an enormous enterprise prior to the arrival of comic cards, the card market experienced a substantial growth between 1990 and 1994 thanks to the greed of speculators took to card collecting as a natural extension of comic books. In 1992, Topps, the second largest manufacturer of trading cards, launched into comic book publication with an adaptation of Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula. Naturally, they also published a series of cards based on stills from the film.31

The synergy of trading cards and comic books only lasted for a short time. The crisis in the direct market coincided with the Major League Baseball strike that lasted almost a year, which dramatically affected the demand for trading cards. In the meantime, the card market found a renewed vigor once the strike was over and profited from the Pokemon hysteria that literally swept across the developed world in the second half of the 1990s. Moreover, it had engendered a new product, role-playing games based on trading cards, such as Magic: The Gathering, which generated a considerable craze at around the same time (though paling in comparison to the Pokemon tidal wave). As for comic cards, their vogue did not survive the crisis of 1994 and they have since become a minor segment of the direct market, with the lion’s share of the card market remaining in sports cards.

Since the end of the 1990s, bookstores and publishers have continually returned to sales enhancement strategies, particularly in the fetishistic forms that had developed between 1989 and 1994. The industry’s hopes are now placed in the development of books and graphic novels, items with a long commercial shelf life that allow for more certain management of catalogs than do comics in their pamphlet form, whose ultra-rapid obsolescence and short commercial life contributed to the under-capitalization of comic book stores. This new perspective has led to an evolution in the commercial culture of comic book stores, who have awoken to the perverse effects of a market built to service the demand of collectors at the expense of the occasional purchasers who are only interested in comic book reading. Market studies undertaken at the start of the twenty-first century have demonstrated that an enormously large pool of untapped customers exists. In questionnaires asking how much time had passed since their last comic book purchases, 75 percent of clients of comic book stores that had been open for at least three years answered that they had only started buying comics in the last three years!32 This signifies that once a comic book store had proven its economic viability, it could in time create new readers for comics, which can open new avenues for the development of the industry. But the expansion of the clientele base also requires changes to the decor of the stores and the recruitment of personnel with criteria other than an encyclopedic knowledge of superheroes. The phenomenon is notable with regard to female customers. A store that is well lit, well kept, and well supplied with graphic novels, where the comportment of the staff was polite and competent, was likely to attract a higher proportion of female buyers than the 12 percent that is average across the industry.33

In Matt Groening’s animated series The Simpsons, Bart Simpson frequents a comic book store called The Android’s Dungeon and Baseball Card Shop, whose obese, unkempt, greedy, and foulmouthed owner (the Comics Book Guy) shamelessly exploits the devouring passion of “fanboys”34 and their investment in an imaginary universe based on fantasy and science fiction. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Matthew Pustz describes a “model” comic book store situated in Iowa City in the first pages of his study of comic book fandom, Comic Book Culture.35 What is familiar about these stores, the parodic representation that lies behind one and the desire for legitimation that structures the other, are the common characteristics of these sites that prolong the disposition of postadolescent masculinity, where each object (comic book, card, figurine) allows a temporary bracketing of reality and its constraints and is attached at the same time to the collective passions that are shared with the other fans present in the store. Stores like the one caricatured in The Simpsons are perhaps less ubiquitous than in the past: the long-term effects of the crisis of 1993–1996 have contributed to a movement that favors the survival of stores seeking to widen their clientele rather than narrow their focus on collectors. The comic book stores of the twenty-first century, much like the publishers, understand that their development lies in favoring a strategy of connecting with the general public (hence the contemporary vogue for graphic novels) and not, as was seen at the end of the 1980s, in trying to transform the general public into comic book collectors.