Cultural legitimation is a complex social process that is difficult to observe because its various modalities refer to distinct realities. Commercial property developers (the cultural industry) and/or fans of various cultural objects instrumentalize the term “legitimation” to designate what are most often nothing more than intermediary stages in the process of inscription into cultural hierarchization. Legitimation is an intricate mechanism that can be broken down into three modalities: visibility, recognition, and legitimacy. These modalities function in relation to one another, and each of the three refers to specific mechanisms within the process of cultural legitimation and they are not, therefore, interchangeable. Common sense, which is the interpretation favored by the aforementioned actors, views each modality as a step in a mono-directional ascent toward the definitive acquisition of cultural legitimacy. But this is a simpleminded conception that subjects diverse art forms and media to a dehistoricized view of consecration, which is actually the type of consecration now enjoyed by the “pure” arts, such as the fine arts (Beaux-Arts: painting, literature, sculpture, and music) and their specialized manifestations (printing, the novel, and the theater). Yet no value is less ahistorical than the purity of the pure arts, which in fact results from centuries-old legitimation processes, during which time phases of consecration, indifference, and even contempt have succeeded one another. The cultural status of the artist as autonomous author rather than salaried artisan is an idea that originated only in the nineteenth century after several centuries of social struggle. This vision of the main agents of cultural production is certainly necessary, but not sufficient to consecrate a cultural object, principally because such consecration arises within the related cultural subfield, among the “artists” and those who publicize their work. The legitimation of any cultural practice requires effects of consecration, that is, phenomena that “confirm” its accession to the dominant cultural hierarchy. If all three modalities of legitimation designate specific types of inscription in the cultural hierarchy, the first two do not in any way guarantee a definitive accession to legitimacy.1

Visibility roughly corresponds to the increase in the number of references made to a cultural object outside of the social space in which it developed. For example, the visibility of rap music grew when it emerged from the ghettos as a topic of news stories, radio and television programs, films, and books. The fundamental criterion of visibility is the mention, the appearance, and the occurrence of a cultural object in a medium or in a form where it manifests its existence to audiences whose cultural habits would not have predisposed them to discover it. Although this is always the first stage of the legitimizing process, visibility does not automatically establish the legitimacy of the object. Visibility may increase as a result of events contributing to the promotion or, on the contrary, censorship of the object. For example, comic books were never more discussed in the American media than between 1947 and 1955, the era in which they were most reviled, but this type of attention contributed to the reduction of their recognition. Visibility can be quantified, but increased visibility does not necessarily constitute a gain in terms of recognition, particularly in the short term. Fads are typical forms of transient visibility, whose effects dissipate as quickly as they arise: the Batmania that existed around the televised adventure series between 1966 and 1968 is a good example.

Visibility is indispensable for the constitution of recognition. Of course, this does not function in a unidirectional manner. A less recognized medium or work derives benefits through its association with a better known medium or work, thereby raising the prestige of the object thus rendered visible. This is what happens when, for example, on rare occasions, televised talk show hosts, who habitually give time to celebrities, invite a highbrow writer or artist to appear, thereby raising the show’s public image. In this way, in certain configurations, visibility literally functions as a form of capital exchanged between media or cultural objects situated at different points on the asix of cultural legitimation, so long as one holds a great deal of visibility and the other a high degree of recognition. But this symbolic transaction cannot take place if one of the parties is too obviously lacking in visibility or recognition. This is what explains why comics adaptations of canonical literary works (of the Classics Illustrated variety) did not contribute to the legitimation of comics at a time when comic books experienced combined deficits in terms of recognition and visibility.

Recognition refers to the social acceptance of a cultural object as an element of the daily environment, to which one is no longer hostile or indifferent. Common usage tends to use the terms “recognition” and “legitimacy” interchangeably, but while every object or medium holding cultural legitimacy automatically benefits from recognition, the opposite is not the case. It can be said that cultural recognition exists from the moment that an object becomes a regular part of the cultural consumption of the majority of the population without encountering significant resistance. “Recognition,” an admittedly vague term, can be used as a synonym for “respectability,” which expresses more clearly the double dimension of recognition: the respectable is what is rendered “important” by the consideration that is accorded to it.

Recognition is strongly conditioned by the relationship between the public and private spheres. The presence of a medium or object in the daily environment is a fundamental criterion of acceptability. This is what explains, for example, the persistence of strong social opposition to certain forms of television content (sex and violence) that are otherwise commonplace in cinema. Movie theaters are public spaces but television sets are located in the private space of the family home (more precisely, in the space of parental decision-making) where individuals in positions of power are, by definition, more able to exercise control over the images to which they are exposed. This gap is analogous to that which historically separated the recognition of newspaper comics and comic magazines. The strips contained in the daily newspapers, a “family-friendly” medium, appeared to be much less objectionable than did comic books, magazines that entered homes often without parental control.

Recognition is also determined by the apparatuses that propagate and perpetuate collective “values,” namely educational, cultural, media, political, legal, and religious actors. Anyone acting as an opinion leader participates in the evolution of the cultural field by relaying the new tastes that result from generational changes in consumers, but also from technological and aesthetic changes that enable new products, and therefore new tastes, to emerge. These mechanisms bring about increased recognition for new cultural objects but also the disaffection for forms that have become too “dated.” A good example is the quasi-extinction of the musical comedy and the decline of the western in the American cinema of the 1950s.

Legitimacy designates the connection of a cultural object to positive qualities in relation to other objects and expressive means that constitute the cultural field. If legitimacy forms the pinnacle of the cultural hierarchy, this is not an intrinsic state but a position that is determined historically relative to other cultural objects. In this respect, legitimacy is at the same time synchronically determined and susceptible to a diachronic evolution upward or downward. There are innumerable examples of writers, painters, and musicians ignored or disdained in their lifetimes that later became celebrated, and vice versa. The degree of cultural recognition at a given moment does not dictate its evolution over time. Legitimacy is the ultimate degree of recognition by the public sphere: it happens when the expressive form, in common usage, evokes only its most consecrated products. The term “literature” only refers to the most elevated segment of literary production, necessitating specialized terms (“popular literature”) to designate less consecrated works. “Painting” a priori evokes the works found in museums rather than the kitsch produced by Sunday painters that, nonetheless, rely on the same medium of expression. On the other hand, despite the undeniable improvement of this medium in the second half of the twentieth century, “comics” much more frequently evokes frivolous, infantile, and rushed productions than Maus or, in Europe, the Italian graphic novelist Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese series. This is not even attributable to seniority. Even though photography (dating from the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839) and film (appearing at the end of the nineteenth century) are roughly contemporaries of comics (appearing in the 1830s), both have acquired a superior degree of recognition than have comics.

These apparent inequalities show how the “positions” occupied by the modes of expression (as opposed to the cultural objects themselves) in the cultural hierarchy can be better defined as centers of gravity independent of the relative positions of various objects within the hierarchy of an expressive form. The aesthetic corpus designated by the term “classical music” enjoys a high degree of legitimation even though it represents an extremely wide range of products, styles, eras, and performances. Moreover, the legitimacy of a mode of expression will be defined by different products depending on the individual. Levels of taste vary according to the class-based habitus, as Pierre Bourdieu demonstrates in Distinction, but at the individual level cultural consumption, they are characterized by the coexistence of practices involving different levels of cultural consecration. French sociologist Bernard Lahire has demonstrated this by citing two world-famous twentieth-century philosophers who represent this cultural heterogeneity: one, Ludwig Wittgenstein, was an inveterate consumer of American B-movies, while the other, Jean-Paul Sartre, was a voracious reader of detective novels.2 It remains no less true that, for example, the “superior” position of classical music in the cultural hierarchy is not affected by the coexistence, within its body of works, of pieces that are appreciated by workers, retailers, teachers, or executives. Likewise we have all heard “commercial” versions of classical pieces far removed from their original context (opera, symphony) as jingles for food or financial products, whose sole goal is to take advantage of the distinction connoted by highbrow works (the same distinction is instrumentalized in non-spontaneous cultural choices, as when parents without musical training of their own have their children learn music).

In the long term, expressive forms benefit (when they are in a superior position) or suffer (when in an intermediate or inferior position) from a much greater inertia along the vertical axis of the cultural hierarchy than do the specific objects produced by them. However, everything occurs as if the freedom for objects to move relative to the expressive form that generated them enables the expressive form itself to be subject to displacements within the cultural hierarchy. When products are received by the public or the media as “artworks” the entire form finds itself elevated. The elevation of cultural status experienced by American comics began thanks to the publication of Maus in the late 1980s. Yet legitimacy within a form’s specific field does not automatically entail legitimacy relative to other forms. It is essential, therefore, to examine how comics, in general, and comic books, in particular, are inscribed in the cultural and social fields of the United States.

Comics, insofar as it is thought of as a domain of cultural production in which individuals are invested, can be analyzed as a “field,” in the sense given to this term by Pierre Bourdieu, that is, as a social space seen through the prism of relations between the agents who participate in it. The field is not an objective diachronic reality but a synchronic state of power relations between actors and institutions engaged in the search for all sorts of capital (economic, but also social and/or symbolic) around a common stake. There are fields that are political as well as scientific, religious, or artistic in any given society. These are themselves constituted by various subfields that embody the various means that allow agents to define their positions relative to each other, thereby reproducing, at a lower level, the general structures of the field in which they participate. Thus, any activity pertaining to culture, in the broad sense of the term, may be linked to an economy of symbolic goods structured by the tensions between the economic and the cultural, the material and the symbolic—the very tensions that structure the artistic field and all the subfields that stem from it. Artistic fields are structured around the tensions between poles of restricted production and large-scale production, between internal consumption (destined for other artists, critics, and connoisseurs) and external consumption (destined for the public), between autonomy (the social status of unique objects benefiting from the singularity conferred on them by their artistic “aura,” in the sense given to the word by Walter Benjamin) and heteronomy (the social status of changeable and interchangeable objects produced by a consumer society). Every artistic field is shaped by the tension between autonomy and heteronomy but its degree of legitimacy, that is, the more or less elevated position within the cultural hierarchy, is a function of the relative weight given to the pole of restricted production with respect to that of large-scale production. This is why, as I previously pointed out, terms like “painting” and “literature” convey a significant cultural legitimacy testifying to the autonomy of these practices within the artistic field, independently of the work produced by Sunday painters or popular literature (in the most derogatory sense of that term). On the other hand, “rock and roll” or “comics” carry the stigma of a low-ranking position in the cultural hierarchy, regardless of the important “works” produced by these forms, but also largely because of their perceived status as a subdivision of the musical field, for the former, and as the bastard child of the fields of literature and illustration, for the latter.

Cultural consecration always begins inside a given field, that is, with their creators and their publics. The following pages address the mechanisms and agents of internal consecration within the comic book field: the prizes, the specialty magazines, the fans, and the conventions.

It has only been since the 1980s that the field of comic books has availed itself of a system of distinction analogous to literary prizes. Prior to that time, comics in the United States were only celebrated within the journalistic field. The Pulitzer board has awarded prizes annually in the category of editorial cartooning since 1922. The prestige that comes with a Pulitzer Prize is considerable, but the criteria guiding the selection of the material have always been quite vague, honoring artists specializing in political cartoons (for example, Herblock in 1979 or Doug Marlette in 1988) as well as comics artists (Garry Trudeau for Doonesbury in 1975 and Jules Feiffer for his Village Voice strips in 1986). Moreover, the Pulitzer board still has not taken steps to recognize comics published outside the daily press. The one exception to this principle, which remains unique to this day, is the award given to Art Spiegelman’s Maus in 1992 in the category “Special Awards and Citations—Letters.”3

Slightly less prestigious than the Pulitzers are the Reuben Awards, handed out by the National Cartoonists Society (NCS) every year since 1946. While the Pulitzers are awarded in a series of small group lunches, the Reuben ceremony is a gala dinner where the big names of comics and illustration gather at an extravagant gala. The Reuben was originally a single prize awarded to the “Cartoonist of the Year” but new categories were created beginning in the mid-1950s. The main ones have been: “Advertising Illustration,” “Comic Books,” “Editorial Cartoon,” “Gag Cartoon,” “Newspaper Panel” since 1956; “Animation” (subdivided into “Feature Animation” and “Television Animation” as of 1995), and “Sports Cartoons” (last awarded in 1993) since 1957; “Special Features” (last awarded in 1988) since 1965; “Magazine Feature and Magazine Illustration” since 1976; “Newspaper Comic Strips” since 1989; “Greeting Cards” since 1991; “Newspaper Illustration” since 1994—and a short-lived “New Media” category awarded from 2000 to 2002. The winners are chosen rotating regional juries, and in the case of the grand prize, on the basis of secret ballots cast by all society members. Because of this relatively inbred operation, the NCS has often been criticized for rewarding popularity rather than excellence.

The history of the awards presented to comic book creators and their works is quite complicated. First to organize such awards were the fans gathered around the fanzine Alter Ego, edited by Jerry Bails and Roy Thomas, in the early 1960s. The Alley Awards, named for the protagonist of Vincent T. Hamlin’s strip Alley Oop, were presented from 1961 to 1969. Until 1964 they functioned as the awards restricted to the community of fans aligned with Alter Ego, but from 1965 onward they were presented at the large comic book convention held annually in New York. Originally determined by the administrators of the prize, nominations were based on responses to preselection questionnaires circulated to readers of fanzines as of 1967. In nine years, the Alleys honored from ten to fifty-five prize winners every year. Beginning in their second year, the prizes were separated into two general areas, one recognized professionals and the other amateurs working in the fanzines. The Alleys disappeared after Roy Thomas, who had done the most work to promote the awards and to ensure their survival, became a professional comic book writer.4

The tradition of prizes awarded by fans began again in 1983 at the initiative of The Comics Buyer’s Guide (CBG), a weekly adzine directed by legendary fans Don and Maggie Thompson. Until 1996, the CBG Awards were presented at the Chicago Comic-Con, but since 1997 they have only been published in the magazine.5 Composed over the years of twelve to fifteen categories with no preliminary list of nominees, the awards go to the artists and works that receive the highest percentage of the vote in any given category. Further, the voting is open to professionals of all types as well as to ordinary readers. As a result of the highly commercial orientation of the magazine, prizes are never awarded to independent creators who lack visibility to the largest part of the comics reading public.

The same characteristics can be found in the Wizard Fan Awards (WFA), presented since 1996 at Wizard World Chicago, the former Chicago Comic-Con that came under the control of Wizard magazine in that year. In keeping with the orientation of the magazine, the WFAs are given almost exclusively to extremely popular artists and publications, principally to superhero comic books. The number of categories—from seventeen to thirty over the years—is the greatest among any organization presenting awards. This abundance testifies less to a broad attempt to promote comics than to an essential strategy of the sponsoring magazine, which encourages its readers to purchase comic books and “collectible” objects by any means possible, one of which is the awarding of prizes to reinforce the readers-collectors-speculators in their reasoning.

Another sign of the industry’s low self-esteem was that awards given to comic book professionals by their peers did not exist until the early 1970s. The first of these were the Shazam Awards, presented yearly by the Academy of Comic Book Arts (ACBA) from 1971 to 1975 during dinners that mimicked the NCS’s Reuben ceremonies. But the issues of legitimacy and identity that chronically afflicted the ACBA, torn as it was between unionist and corporative callings, did not enable the peer-celebration ceremonies to raise the image of comics books among the public or even among professionals themselves (see chapter 12).

It was not until 1984 that an internal award system was put in place by the industry’s artistic and commercial actors. That year, the magazine Amazing Heroes (published by Fantagraphics, like The Comics Journal) launched the Kirby Awards, named after the artist Jack Kirby and supported by the artists himself and his wife Roz. Composed of ten different categories (eleven in the first year), from 1985 to 1987 these prizes were presented to works produced in the preceding year. They were the first to recognize the innovations of the new wave of creators working for Marvel and DC (notably Frank Miller and Alan Moore) as well as the then increasingly numerous independent publishers, including Aardvark-Vanaheim (Dave Sim and Gerhard for Cerebus), First (Steve Rude for Nexus), Eclipse (Scott McCloud for Zot!), Comico (Dave Stevens for Rocketeer), and Fantagraphics (Los Bros. Hernandez for Love & Rockets). In retrospect, one is impressed by the acuity with which these awards distinguished the creators who would come to define the canon of comic books at the end of the twentieth century.

In 1987, a conflict about the paternity of the prize arose between Dave Olbrich, who had remained its administrator even though he no longer worked for Amazing Heroes, and Fantagraphics owners Kim Thompson and Gary Groth. The dispute led to the dissolution of the institution, on the recommendation of the Kirbys themselves, and its immediate rebirth in two distinct forms. On the one hand, the Harvey Awards, originally coadministered by Fantagraphics, the comic book store chain Lone Star Comics, and the Eastern Regional Comic Book Retailers Association (ERCBRA), and on the other, the Will Eisner Comics Industry Awards, created by Dave Olbrich, sponsored by ERCBRA, and managed by a board consisting of personalities attached to museums and universities who were originally chosen by Will Eisner himself.

The Harveys, named in honor of Harvey Kurtzman, were at first the direct offspring of the Kirbys, at least to the extent that they remained under the stewardship of Fantagraphics. This ended in 2003, when they were sponsored by the distributor Diamond Comics, DC, four independent publishers (Dark Horse, Bongo Comics, Slave Labor Graphics, and Cartoon Books), and a Web site manufacturer (Angelfire). Since the beginning, only creators have been allowed to take part in the voting. Awarding prizes (in thirteen to twenty-four categories) that recognize people and products from both the mainstream and alternative ends of the industry, the Harveys were presented at various conventions over fourteen years. Since 2003, the prizes have been handed out at the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art (MOCCA).6

The Eisner Awards initially retained from the Kirbys a system in which the winners were chosen by distributors, publishers, and editors, but they were only awarded twice under this system. They joined forces with the San Diego Comic-Con in 1990 and since that time, the nominations have been made by a five-member committee including artists, journalists, retailers, distributors, and other industry professionals. The deciding votes are open to anyone falling into one of these categories. The Eisners are presented at a gala soirée in a large auditorium that is open to the public, but without the pomp and circumstance that accompanies an event like the Oscars. In contrast to the Harveys, which reward commercial success and creative originality, and as a result of the important role of business people in the selection process, the Eisners have traditionally recognized mainstream works and individuals, even though many creators from the alternative end have been both Harvey and Eisner award recipients. Although the Eisners have often been accused of pandering to collectors by rewarding categories removed from printed comics (such as the award for statues depicting comic book characters), a comparison of the winners of the two awards highlights the numerous similarities between them and provides a fairly clear-cut image of what could be called “expanded popular production” in the 1990s. The most original (or least standardized) Marvel and DC products coexist with the least avant-garde independent publishers (such as Dark Horse and Cartoon Books) and atypical material attractive to the general public, like the work of British writer Alan Moore or the comics of Dan Clowes and Chris Ware. In all instances, the Eisners and the Harveys define the contours of a middlebrow production that occupies the intermediary position between the purely “commercial” products presented with Wizard-type awards, and the “cutting edge” material distinguished by the Ignatz Awards.

Named after the mouse who was one of the protagonists of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, the Ignatz Awards have been presented at the Small Press Expo (SPX), a convention reserved for independent publishers, every year since 1997. Since the Ignatzes are intended to promote independent creation, the nominations are made by a jury of five artists (anonymous until the announcement of the results) that changes each year. The jury performs a process of preselection according to its own tastes but also taking into consideration suggestions from the public (without necessarily integrating those into their final choices). The final vote is open to any member of the public or professional attending SPX.7

The comics industry avails itself of a number of other, more low-profile awards. Among these, the most notable are those presented at the San Diego Comic-Con in conjunction with the Eisners. These prizes were associated with the convention long before the connection was made with the Eisners in 1990. Created in 1974, the Inkpot Awards recognize institutions and individuals for their direct or indirect influence on comics through illustration, animation, science fiction, television, and cinema. Dozens of comics creators have received Inkpots, including winners as diverse as Kirk Alyn (1974), the first actor to play Superman, filmmakers Frank Capra (1974) and Francis Ford Coppola (1992), or the National Film Board of Canada (1980). One of the reasons behind this eclecticism is that, even though the convention in San Diego used to focus on comics in general and comic books in particular,8 it has always welcomed television and film, offering its participants opportunities to view rare or old films that it was difficult to see in the days before the widespread adoption of home video.

In 1982, the convention organizers expanded the Inkpots ceremony by adding a prize awarded by the West Coast Comics Club to recognize young artists: the Russ Manning Most Promising Newcomer Award, named in honor of the California-based artist who passed away the previous year. In 1984 they also added the Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award. Named for the Warner Brothers animator who passed away that year, it is given to recipients who are distinguished by their commitment to praiseworthy causes, ranging from the defense of free speech (the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund in 1991 and Frank Miller in 1998), to the donation of original art to charity auctions (Alex Ross in 2003), and including the production of works addressing political issues (Joe Kubert for Fax from Sarajevo in 1997).9

A final prize presented at San Diego—although not during the convention’s award ceremony—should be noted. The Friends of Lulu Award has been presented since 1997 by the association of the same name as a way to promote female comics creators and comic books created for women. The members of the association make nominations and a committee of board members cast the final votes. With four categories (three since 2001), these awards have contributed to the consolidation of the feminine side of the American comics canon, obscured in the history of the medium by the extremely low number of female artists.10

These prizes function primarily as indexes of internal recognition and not, as is the case with Oscars and the Hollywood film industry, as a showcase for the entire industry. With the exception of the Pulitzer given to Maus in 1992, it would be difficult to find another comics award that has enjoyed any comparable long-term media coverage in the United States. Even the Eisners ceremony, which is presented as the high point of the most important annual gathering of the comic book industry, is not reported on by the local press in San Diego, and even less so by the national press. Consecration operates here within a subcultural logic, not as the manifestation of a dominant cultural practice whose rituals of consecration are relayed by the general media, as is the case with the announcement of literary prizes, for example.

In Seduction of the Innocent, Fredric Wertham wrote: “I have known many adults who have treasured throughout their lives some of the books they read as children. I have never come across any adult nor adolescent who had outgrown comic book reading who would ever dream of keeping any of these ‘books’ for any sentimental or other reason” (89–90). And yet, the internal consecration of comic books has largely resulted from the growth of a community of “fanatics.” They have exerted a considerable influence on the history of the field by promoting the visibility of comic books among the public and patronizing the network of comic book specialty stores fostered by the direct sales distribution system since the mid-1970s.

The term “fandom” defines a community formed by individuals who support a mass medium with intense personal passion. The existence of fandom is a twentieth-century phenomenon specific to the mass culture of industrial societies. Urban ways of life, the development of mass education, of communications and the cultural industry (itself correlative to the expansion of leisure time), and the decline of religious practices, have fostered a context in which individuals immerse themselves in common interests created by the culture industries.

The study of fandom as a cultural phenomenon presupposes several preconditions:

• Dehistoricizing and simplifying the phenomenon should be avoided. For example, it is necessary to preserve the distinction between collector and fan. Collecting is only one activity, certainly a widespread one, among the numerous behaviors of the fan. Practically all fans are collectors, but the opposite is not necessarily true. Personal forms of investment that exceed simple accumulation can be observed among fans.

• At the individual and collective levels, fans do not constitute an ahistorical reality: they change over time, both because of individual changes and sudden or progressive shifts in mass culture. Comic book fans in the mid-1950s were not the same as the fans at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

• Fans should be defined, notably by comparison with casual readers, by the community that they form and in which they are conscious of participating, even if they are not personally acquainted with all of their kind and do not engage in all the activities that shape the existence and vitality of fandom (such as reading, collecting, publishing fanzines, or organizing conventions).

• Although the fans’ activities may appear irrational to nonfans, the observer should always resist the temptation to “pathologize” the interpretation of behaviors: they do not reflect any abnormality but are often individual strategies aimed at constructing the singularity of the objects of their passion.11 In this respect, psychoanalytic approaches, by reducing behaviors to the play of emotions and urges, has been an obstacle in the construction of a coherent sociological understanding of fans. There is such a thing as pathological fan behavior but it concerns only a small minority of individuals and should by no means be regarded as a universal trait (unless one is prepared to advocate the institutionalization of all sports fans or all stamp collectors, too).

In the case of comic books, what attracts fans? Not all readers are fans and vice versa. During a round table organized at one of the first comic book conventions in 1965, publisher James Warren explained how he had lost millions of dollars and narrowly avoided bankruptcy when he allowed Forrest J. Ackerman to edit the magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland according to the wishes and suggestions expressed in fan letters.12 Warren’s anecdote merely highlights this economic reality: a publisher must draw a distinction between readers, letter writers, and fans. If the first group contains the other two, fans and letter writers overlap only partially. As for the size of the three groups, they are extremely unequal. Fans are a minority of readers, and letter writers an even smaller group, made up primarily of fans but with a minority of nonfans. It is essential to have a clear idea of the numerical relationship between these three types of consumers as it is inversely proportional to their impact on the economics of the field. The actual readership is an informal community in which a silent majority coexists with a vocal minority, whose ideas and preferences are not necessarily in line with those of the majority of the purchasers of a given title. Fans maintain an intense relationship with the objects of their passion that is different from the desire for simple distraction experienced by the vast majority of readers of any magazine. Insofar as the fans partake in a “cultural activism” that contrasts with the passivity of the majority of readers but does not necessarily reflect the interests of this silent majority, they must be understood as distinct individuals within the overall readership. This is also the reason why it is very difficult, if not impossible, to construct a reliable representation of occasional or non-passionate readers, even though they account for the real majority of consumers of this type of cultural production.

If “popular literature,” in the contemporary sense of that term, was born in the middle of the nineteenth century around the serial novel, the first fans must have appeared around the same time. But we have few indications of their activities. They did not form a structured community conscious of its own existence and capacity to inflect the evolution of the field that was the object of their passions. Nonetheless, we can liken the behavior of twentieth-century fans to that of those French women who, in the mid-nineteenth century, saved the pages of serials published in the daily newspapers and stitched them together in order to be able to reread them, lend them out, or exchange them for similar “books.”13 The great publishing revolution of the nineteenth century in Western countries was predicated on the transition between the intensive reading of a small number of works, characteristic of older times (such as the Bible or Shakespeare’s works), and the extensive reading of best-selling publications, plentiful, quickly consumed, and frequently replenished. In the United States, this phenomenon began in the Jacksonian period with the first story papers.

The main factor accounting for the appearance of fandoms was the constitution of the new sociocultural category of adolescence after the First World War. The prosperity of the 1920s and the growing percentage of the population educated beyond primary school accelerated the growth of mass culture. As young people became increasingly numerous in urban and semi-urban areas, they proved bigger consumers of mass cultural commodities than prior generations, who were generally less educated and more distant from nonreligious reading. The first fandom, in the contemporary sense of the term, coalesced around dime novels. The first written evidence of it dated back to the 1920s, notably with the newsletters published by a Massachusetts fan named Ralph F. Cummings. After publishing Novel Hunter’s Yearbook annually from 1926 to 1931, he produced Reckless Ralph’s Dime Novel Round-Up, the main magazine about dime novels, which is still published to this day.14 Nonetheless, this movement remained little known, probably because it was too steeped in nostalgia. After the First World War the dime novel was already a cultural relic of the Gilded Age rather than a staple of the Roaring Twenties.

Fandom, as the collective expression of young people rooted in the present, was to develop first among individuals who believed in the promise of the future. During the prosperous 1920s and the depressed 1930s, mass culture propagated the daydreams of modernity and, particularly, of science fiction literature. The science fiction fan community, the forerunner of comic book fandom, emerged between January 1932 (the publication date of the Time Traveler, the first science fiction fanzine, which was put together by two future DC editors, Mort Weisinger and Julius Schwartz) and the World Science Fiction Convention that assembled 185 attendees in New York on the Fourth of July weekend in 1939.15 The participants shared a common attraction to the science fiction pulps that had multiplied in the wake of the first issue of Amazing Stories, published by Hugo Gernsback in March 1926. They were principally adolescents and young adults but their movement was to grow despite the aging of its founders. The mechanism was launched and science fiction fans have never stopped increasing in numbers, as their favorite genre became one of the main sources of material on television and in film.

Comics fandom was born in the bosom of science fiction fandom but it established a close relationship to the comic book format from the start. According to fandom historian Bill Schelly, the first comics fanzine was published by science fiction fan David A. Kyle under the name Fantasy World in February 1936. This mimeographed pamphlet contained only science fiction comic strips drawn by Kyle.16 This magazine, which included no information whatsoever about newspaper comic strips, comic books (which were at a very early stage of their development, two years before the first appearance of Superman), cartoonists, or publishers, epitomizes the prehistory of the comic fans’ movement. Fantasy World was a cartoon-strip variant of the fanzines containing fan fiction. At this stage, the science fiction fan had not yet yielded to the comics fan.

The first fan publications that offered information on comics and the publishing world were released by James V. Taurasi in 1939. In Fantasy News and Fantasy Times, he published information about the plagiarism lawsuit filed by DC against Victor Fox and announced forthcoming new releases from Centaur. In response to fan publications, Centaur, in the sixteenth issue of Amazing Mystery Funnies (December 1939), introduced a section titled “Looking Over Your Magazines: A New Department for Boys and Girls Who Publish Their Own Magazines,” which was written by John Giunta, a young science fiction fan who later became a professional comic book artist.17 According to Schelly, the first fanzine specializing in comic books, Comic Collector’s News by Malcolm Willits and Jim Bradley, was published in 1947 and was released at irregular intervals until the end of the decade.

The beginning of the 1950s was the high point of the first age of comics fandom. An important development was the publication of Ted White’s The Story of Superman in 1952. This pamphlet, which was apparently the first detailed article about a comic book character, was revised by its author several times before being distributed in an edition of fifty copies in 1953 as The Facts Behind Superman, World’s Greatest Adventure Character. This period was also notable for the production of fanzines dedicated to the output of EC. From autumn 1952 to December 1953, J. Taurasi published Fantasy Comics, a monthly bulletin dedicated to all science fiction comics of the period, particularly the EC titles. In 1953, two issues of EC Fan Bulletin were published by Bhob Stewart. This fanzine inspired Bill Gaines to create the EC Fan-Addict Club and its official publication, The National Fan-Addict Bulletin, of which five issues were released between November 1953 and December 1954. Many fanzines dedicated to EC titles appeared in the months that followed: news bulletins from two young fans (EC Fan Journal by Mike May and George Jennings’s EC World Press) and more elaborate fanzines, like Hoohah!, Potrzebie, Foo (produced by Robert Crumb and his elder brother Charles), Klepto, Wild!, Blasé, and Squire, were all produced by young enthusiasts.18

We know, from numerous recollections, that during the 1940s a considerable number of readers traded or resold old comic books. At the same time, for many preadolescents, the collective reading of comic books bought by one or the other was a favorite pastime, less expensive but nonetheless just as stimulating as going to the movies. Indeed, in this period, secondhand book dealers sold used comic books for prices ranging from one to five cents. It was more cost efficient to pick up two or more old comic books promising hours of entertainment than a movie theater ticket costing ten cents, a sum that not all children could necessarily obtain. An embryonic comic book collectors market formed from the early 1940s involving a handful of specialized used bookstores—Pop Hollinger in Concordia, Kansas, from 1940, Claude Held in Buffalo, New York, from 1946—and a growing number of fans who circulated want lists via science fiction fanzines.19

After the war, some preadolescents became strongly interested in comics. The literary and film critic Robert Warshow, who wrote a long article on the controversy about comic books, told of the way that this interest manifested for his son Paul. The boy, at the time aged twelve years, was himself a member of the EC Fan-Addict Club and convinced his father to take him and his friends to the publisher’s offices where they saw artist Johnny Craig and shook the hand of publisher Bill Gaines.20 Warshow writes:

At various times in the past he has been a devotee of the Dell Publishing Company …, National Comics [DC] …, Captain Marvel [Adventures], The Marvel Family, Zoo Funnies (very briefly), Sergeant Preston of the Yukon, and, on a higher level, Pogo Possum. He has around a hundred and fifty comic books in his room, though he plans to weed out some of those which no longer interest him. He keeps closely aware of dates of publication and watches the newsstands from day to day and from corner to corner if possible; when a comic book he is concerned with is late in appearing, he is likely to get in touch with the publishers to find out what has caused the delay. During the Pogo period, indeed, he seemed to be in almost constant communication with Walt Kelly and the Post-Hall Syndicate, asking for original drawings (he has two of them), investigating delays in publication of the comic books … or tracking down rumors that a Pogo shirt of some other object was to be put on the market … During the 1952 presidential campaign, Pogo was put forward as a “candidate”, and there were buttons saying “I Go Pogo”; Paul managed to acquire about a dozen of these, although, as he was told, they were intended primarily for distribution among college students. Even now he maintains a distant fondness for Pogo, but I am no longer required to buy the New York Post every day in order to save the strips for him.21

After the demise of EC in 1955, various fanzines dedicated to the now legendary publisher continued to appear and disappear. This highlighted changing times. Science fiction fanzines had been the main source of information on comic books until the end of the 1950s. After the war the term “double fans” appeared, referring to individuals who were equally passionate about science fiction and comic books. The first age of fandom remained largely hidden, first because of the fans’ limited economic means and the reduced visibility of publications, second because of the discrepancy between the most active fans and the actual readership. Thus, after receiving responses to an ad that they placed in EC magazines, the creators of the fanzine Potrzebie, Bhob Stewart and Ted White, realized that the average age of fanzine readers was between nine and thirteen years, while they had imagined a much older public. Disappointed by this brush with reality, they gave up when EC went under.22

There was a genuine gap between adolescent fans and the entirety of the readership. A study published in 1949 by two psychologists, Katherine M. Wolf and Marjorie Fiske, provided a bleak image of heavy readers of comic books. Based on interviews with a sample of children, they identified three categories: fans (37 percent), moderate readers (48 percent), and others, who were indifferent or hostile to comics (15 percent). Their vision of fans was openly pathologic. According to them, passion for comic books was a “violent and excessive” interest that desocialized children and enabled them to find divine protective figures in comic book heroes. Moreover, their analysis established correlations between the physical size of comic book readers (one fan in two was small for his age) and their social position (those coming from families in which the parents were professionals were less likely to become fans than were others). According to this study, whose methodology reveals the authors’ unconscious elitist biases, fans were engaged in a cultural practice akin to drug addiction and which was aggravated by biological and social stigmas. Evidently these conclusions would have been endorsed by Fredric Wertham.23

The impetus behind the second wave came from a small group of adult science fiction fans who used to enjoy comic books in their childhood and who found their interest revived by the resurrection of superheroes at DC in the late 1950s. The new generation of fans contributed articles about the comics of the 1930s and 1940s to Xero, a science fiction fanzine published by Richard Lupoff in New York since the autumn of 1960,24 and the fanzine Comic Art published by Maggie Curtis and Don Thompson in Cleveland since 1961 (they were the same couple who became the editors of Comics Buyer’s Guide more than twenty years later). Simultaneously, DC, Gold Key and, later, Marvel started publishing fan letters in their titles, thereby enabling older, or at any rate, more mature fans to contact one another. In March 1961, six months after the appearance of the first issue of Xero, Jerry Bails (born in 1933), a graduate student in Detroit, and Roy Thomas (born in 1940), also a student in Missouri, released Alter Ego, the first fanzine exclusively dedicated to comic books or, more precisely, to Golden Age and contemporary superhero comic books. It was distributed among fans born in the 1930s and 1940s, who became aware of fellow comic book lovers from the same age bracket, but also of younger readers full of enthusiasm for the innovations at Marvel and DC. Six months later, in September, Bails launched the Comicollector, an adzine that was to be the commercial arm of the generalist magazine Alter Ego. In March 1962, he also launched The Comic Reader, an irregularly produced news bulletin containing information on new releases and projects announced by the publishing houses.

The movement initiated by Bails was less disparate than its counterpart of the 1950s. Fanzines dedicated to comic books began to multiply given the varying interests of comic book fans. At first sight, the three titles created by Bails illustrated the sundry directions that a fanzine could take: a historical and critical revue (Alter Ego), an ad-driven magazine promoting the buying, selling, and trading of comics (Comicollector), or a news magazine about comic books (Comic Reader). To these three types can be added fanzines made up, in whole or in part, of comics produced by fans, or ama-strips.25 The various kinds of fanzines were determined by the proportion of news, editorial material, ads, and amateur comics, from the highly diversified (gen-zine, for “general fanzine” where editorial content nonetheless predominated) to the more highly specialized (articlezine, ad-zine, ama-strip zine). Among the “biggest” fanzines published up to the 1970s was Fantasy Illustrated, an offset ama-strip zine created by Bill Spicer in 1964. It was renamed Graphic Story Magazine with its eighth issue published in autumn 1967 and took a new direction influenced by psychedelic culture. Its pages featured diverse material, ranging from avant-garde underground comics, like those by Vaughn Bodé and the Canadian artist George Metzger, to sophisticated reviews written by Richard Kyle, to interviews with major artists like John Severin (#13) or Howard Nostrand (#16). The intellectualization of the discourse on comics ushered in by this magazine was one of the main inspirations for Gary Groth when he created The Comics Journal in 1976.

The opposite approach to comics was epitomized by The Buyer’s Guide for Comics Fandom. Launched in 1971 by Alan Light, a young Illinois fan, this magazine proved to be the greatest business success in comics fandom. The monthly newsprint tabloid quickly became biweekly and then weekly by 1975. The Buyer’s Guide for Comics Fandom took up the successful formula that The Rocket’s Blast Comic Collector, run by Floridian Gordon B. Love, had initiated in 1964, a magazine in which comics-related advertising occupied much more space than did news and reviews. After twelve years of uninterrupted prosperity, Light sold it to Krause Publications in 1983 and its editorial reins were taken over by Don and Maggie Thompson, the fans who had created Comic Art in 1961.

From autumn 1960 to autumn 1966, 192 fanzines entirely or partially dedicated to comics appeared, generating 724 issues. In 1971, the number had grown to 631 titles for 2720 issues, of which about 2000 were exclusively about comics.26 Despite the very unequal reach of these publications (the term “crud-zine” was employed to designate those in which the quality left much to be desired in terms of form and content), the scope of this editorial phenomenon testifies to the vitality of comics fandom during the 1960s. It can be inscribed more generally in the even larger traditions of amateur journalism appearing in the 1930s under the generic name APAs (that is to say, Amateur Press Alliances or Amateur Press Associations). In these limited reach associations, each member was responsible for periodically producing, in a prescribed quantity, a minimum number of pages that were to be sent to a central mailer, who collected the contributions, manufactured copies for all of the members of the association, and then redistributed to each of them the volume formed by the collective contributions. It seems that the first APA assembled by fans of popular literature was Fantasy Amateur Press Association, founded in the 1930s by Donald Wollheim and which continued to function into the 1970s.27

This was the format that Jerry Bails chose to pursue with his fanzine publishing activities. In 1963, he gave up the editorship of the three fanzines that he had founded in 1961 and 1962, and whose simultaneous duties he had quickly found oppressive. The first edition of Capa-Alpha, consisting of the contributions of six writers (including Bails), was made available to members in October 1964. From the second issue Bails was ready to welcome all forms of engagement with comics: comics made by fans, critiques of fanzines themselves, reports on fan gatherings, and even fan fiction, a common element in science fiction fanzines which had, on occasion, found itself in the pages of comics fanzines.28 A contributor destined to have a big future was the author of “I Was A Teenage Grave Robber,” published in several installments of the fanzine Comics Review in 1964 by a young writer from Maine named Stephen King.29

This dimension demonstrates the plurality of functions that fanzines played in the period: a space in which a profound interest in genre could be expressed, they also constituted a space in which future professionals could exercise their skills in apprenticeship, whether they later became writers, artists, or editors. The first two fans to make the leap to professionalism were E. Nelson Bridwell and Roy Thomas, hired as assistant editors by DC in 1964 and 1965 respectively. The second half of the 1960s coincided with a period of intense renewal of creative personnel in the comic book industry, during which time a number of creators who had been active in the field since the Depression retired or were replaced by younger successors. In this context, the fanzines constituted a minor league from which publishers could find young creators born after the war, who had been shaped since birth by the visual, graphic, and mental universe that were generated by comic books. Almost all of the “big name” writers and artists who appeared as professionals since the 1970s spent at least some time in the fanzines, quite the opposite of the experience of their predecessors in the period between the 1930s and 1960s who became professionals at the end of their schooling. On the other hand, a number of fans (including Biljo White, Grass Green, Alan Hanley, Ronn Foss, Landon Chesney) who published work in the fanzines of the early 1960s never became professionals. In addition to the fact that their drawing abilities did not meet the needs of the large publishers, these men, for the most part born before the war, had already committed to professional careers that had little to do with comics and were not able, or not willing, to take the same steps toward professionalization as the younger artists entering the market at the turn of the 1970s.

A fundamental element in the development of fandom was the multiplication of conventions beginning in the 1960s. Here again, the model followed that of science fiction conventions that, since the end of the 1930s, had developed a format featuring large sales halls (books, magazines, photos), enlivened by panels on subjects of interest to fans. The first comics conventions (often shortened to comicons) took place on May 9 and 10, 1964, in Chicago and May 24, 1964, in Detroit. More or less organized to please adolescent fans, each attracted several dozen participants and offered, in addition to the merchandise stands, the projection of old films. The first convention in New York took place in July of the same year. Despite a not very favorable day (a Monday) and a short time span (a single afternoon), it allowed attendees to interact with three representatives of Marvel (including Spider-Man cocreator Steve Ditko) as well as to buy and sell comic books. The largest science fiction conventions that took place during the same period were infinitely more attractive to comic book fans. Older and more polished, they attracted hundreds of participants and “celebrities,” some of whom, including writers and artists, worked on comic books.

Excepting the Detroit Triple Fan Fair (which, as its name indicates, brought together fans of film, science fiction, and comics), the first truly important gathering dedicated to comic books took place in New York the following summer under the sponsorship of the Academy of Comic Book Fans and Collectors (founded by Jerry Bails in 1961 in an attempt to unite the community of fans). It took place on July 31 and August 1 and attracted several hundred attendees including a number of important professionals, notably those from DC. The size of the event, and its visibility, bore no relation to the previous year’s edition for a simple reason: a few months before, the New York Times, Newsweek, and the rest of the press had discovered the world of fans who were willing to pay astronomical sums for old comic books.30 From that point on, the movement has never ceased to continue growing. The growth of conventions of all sizes in the eastern part of the country coincided with the establishment, in 1968, of the Comic Art Convention organized by Phil Seuling in New York on the Fourth of July weekend. For several years this event was the most important one in the comic book world, until San Diego took on that role in the 1980s.

The West Coast witnessed a slower growth forth the comic conventions, despite the fact that it benefited from its proximity to San Francisco, the original home of the underground comics movement. The small conventions organized in San Diego in March and August 1970 by a handful of local fans experienced an unexpected success. Thanks to its proximity to Hollywood and the support of big names living in California, like Jack Kirby, Ray Bradbury, and Charles Schulz, the San Diego Comic-Con (SDCC) was characterized from its beginning by an openness to cinema, television, and newspaper comic strips that was superior to their homologues on the East Coast, who profited from their proximity to New York, the historic center of the comic book industry.31 The large New York convention run by Phil Seuling was held fifteen times, after which time San Diego became the most important annual event for both fans and professionals. Since the end of the 1990s, SDCC has witnessed a very perceptible transformation into a celebration of all forms of popular culture, the annual growth of the space occupied by the convention within the San Diego Convention Center accompanied by the even more rapid expansion of the space given over to television and film properties relative to the space reserved for comic books.

What is the special attraction of a convention for a fan? The first thing is the tangible materialization of the cultural phenomenon that is part of the everyday life of fans but which can also be made manifest to laypeople, and curious or amused visitors to the event. At a step above specialized bookstores, conventions concentrate the diverse types of investment in comic books in the largest sense—the possibility of acquiring comic books, figurines, gadgets, autographs, and the like is added to the function of a forum of exchanges (verbal and monetary) and communication between individuals in a cultural system. Although all of the participants are there because of an interest in comic books, it is possible to observe the existence of hierarchies, even barriers, between “specialties.” With the exception made by a minority of particularly wealthy or extravagant individuals, the majority of fans practice an implicit classification in their priorities: rare are those who simultaneously collect original artwork, figurines, old comic books, trading cards, and signatures. The majority are interested in one, two, or three types of products; the other objects hold only anecdotal interest in their eyes essentially because their identity as a fan is constructed around certain objects to the exclusion of others. This is why even the superficial observation of a convention troubles the conception of the fans as monolithic and interchangeable characters. The apparently endless lines of individuals waiting to have a book signed or to receive a sketch (often for a price) from a particularly popular artist provides a totalizing vision of a community that sits, in fact, at the intersection of a tremendous diversity of individual investments, each demonstrating in a certain way the integration of a particular passion into his identity.32

For the outside observer, American comic book conventions may even look like happenings. Following a tradition inaugurated by science fiction conventions from before the Second World War, they constitute an opportunity to masquerade as recognizable comic book or film characters for a certain number of participants. The practice of masquerade, of which there is photographic evidence dating back to the 1960s and which was at the heart of the Halloween parade in the small town of Rutland (Vermont),33 involves individuals of both genders (even if the overwhelming majority of attendees are men) and all ages. It has been institutionalized at a number of conventions by the awarding of a prize for the best costumes. This is another form of investment, “carnivalesque” one could say, in the same cultural system.

Internal consecration does not signify a consensus between all actors involved with a sector. The multiplicity of specialty magazines about comic books demonstrates the parallel forms of investment of fans as well as the gaps that exist between the conceptions that diverse actors in the field have with regard to engagement in the comic book sector as an economic and/ or cultural practice.

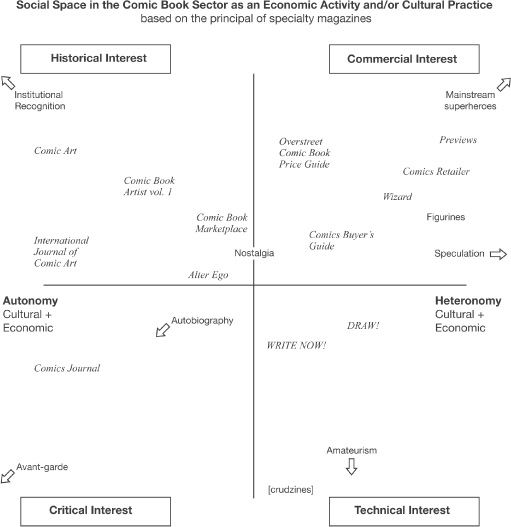

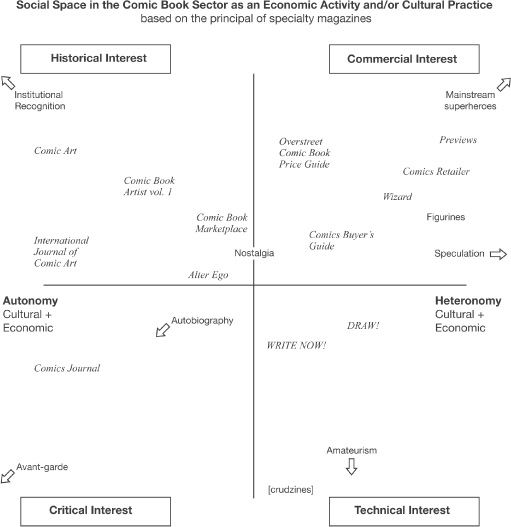

The space for forms of engagement in the comic book sector as an economic and/or cultural practice in the United States can be represented by a perpendicular axis representing the logic of cultural consumption in a general social space: its x-coordinate represents that opposition between, at one end (situated on the left in this schema), pure production—artistic, autonomous, destined for producers, and based on a vision of creation that rejects economic motivations, recognizing only the vision of art for art’s sake—and at the other pole (situated on the right), large-scale production—commercial, heteronomous, structured by an attention to the real or imagined demands of the public. The ordinance of the schema illustrates the volume of social capital involved in cultural consumption (as the horizontal axis represents the structure) where the opposition between the high and low parts takes on the schematic gap between the dominant and the dominated, that is, the position of cultural consumers in social space.

The resultant topography made possible by this schema allows the comic book field to be divided into four general kinds of cultural investment: commercial, technical, historical, and critical. Although each magazine is inscribed in a distinct sector of the overall field, fans at the individual level are susceptible to share one or more of these types of interest.

Two main types of publications dominate the diverse forms located in the commercial sector. Previews, a thick magazine, is nothing more than a catalog of products distributed by Diamond, while Comics & Games Retailer is a magazine that touches upon all aspects of managing specialized bookstores. These are primarily read by booksellers and possibly by “professionals,” that is, by the public who give the most thought to new and recent publications. Wizard, a monthly created in 1991, appears to be only concerned with contemporary mainstream titles. It excludes from its pages everything that does not touch on superheroes, heroic fantasy, science fiction, and fantasy, placing its emphasis on artists at the expense of writers and offering in each issue a price guide that constantly updates the speculative tendencies that dominated mainstream comics titles over the past twenty years (in contrast to the Overstreet Price Guide which strives to offer a much more complete inventory of all American comics published since the nineteenth century).

These publications are situated in the strongly heteronomous sector of the field. Each exalts, in its own way, the consumerist dimension of comic book reading by positioning itself in close alignment with the economic logic of the largest publishers whose basis is the commercial exploitation of superhero characters that are indefinitely reusable. On the other hand, they have less to do with comic books (and comics) than with their derivative products, such as figurines, role-playing games, collectible cards, clothing, and other objects based on popular characters or upon concepts derived from comic books. The investment of fans who read these magazines regularly is primarily financial and corresponds with a minimal interest in the expressive possibilities of the form, thereby embracing the most commercial of comic book formulas, but, on the other hand, participating in the mercantile logic of the star system through which certain artists and characters mechanically confer an added value to the magazines where they are turned into stars, thereby fueling the growth of a speculative market into which buyers immerse themselves to the profit of publishers and retailers.

In this sector of the field, the weekly Comic Buyer’s Guide occupies a position less markedly heteronomous. Even though it is the oldest still existing adzine (having taken over from the Buyer’s Guide for Comics Fandom, which began in 1971), it offers, beside the ads and the articles addressing the collector’s market, op-ed pieces, reviews, and often thorough articles on the history of comic books. In opposition to the three magazines previously discussed, The Comic Buyer’s Guide demonstrates the distinction that can be drawn between the speculators, entirely oriented toward the present and the hypothetical future orientation of the market, and the “collectors” in the 1960s sense, who are directed toward past production and who seek out older comics for their contents at least as much as for their monetary value. This is why it is necessary to position “nostalgia” as an investment form positioned between the commercial and the historic.

This area is characterized by the individual’s intense relationship not to comics as an entire set of creative possibilities, but to one of its constitutive formal properties, writing or drawing. It is drawing that exercises the strongest fascination for the majority of fans. Among those who do not know how to draw, the aesthetic sensation is converted into a “cult” organized around the personality of the artist that manifests as a quest to find all of the magazines upon which he worked, as well as in the search for interviews with the artist, and eventually to the acquisition of original art. Among those who know how to draw, or who aspire to, a servile relationship toward the style of the admired creator often develops, the imitation of which can appear to the aspirant as a horizon that can never be attained. The appeal of comics to young artists is generally an attraction to drawing and, if need be, to narrative techniques (the breakdown of stories into pages, framing, the sequencing of panels) which leaves the expressive dimension of the stories to the side, retaining only the superficial aspects. An excessive, but revelatory, version of this type of investment is amateurism, in both the positive sense (the attempt to do something as the professionals do) and the negative sense (the failure to do something as the professionals do) of the term, which can be seen in fanzines, and particularly in the most mediocre of those, termed “crudzines.” In this sector of the field, investment is based on the surface perceptions of comics that appeal to imitation. Those who publish fanzines ape the professional magazines, novice artists seek to appropriate the styles or the tricks of established artists, young writers try to assimilate the methods of writing. It is principally to these readers that the magazines DRAW! (subtitled “The ‘How-To’ Magazine on Comics and Cartooning,” launched in 2001) and WRITE NOW! (“The Magazine About Writing for Comics, Animation and Sci-Fi,” launched in 2002), dedicated to examples and lessons provided by creative professionals, are targeted. Less valorized than drawing in the general economy of the field, writing seems to offer a poorer creative and commercial future than the mastery of drawing, which is, after all, the apparent economic motor of the industry, more or less located on the economic side (on the right-hand side of the schema). But its relationship with literature brings it closer to the cultural side of the field, while the mastery of graphic techniques responds to the commercial demands of the large-scale production that are less valorized.

Here, judgment of the form is not autonomous, nor is it minimal in relation to the judgment of the total package. In the matter of taste, the total appreciation of a work is heavily determined by its drawings, the most immediate exterior index of the continuity between creators and creation, between producer and product, interpreted as the mark of an “author” in the strongest sense of the term. The judgment of taste thus formulated produces an implicit hierarchy that places visual elements at the summit of the critical chain, in first position among the evaluative criteria of a comic, and reverberate in the appreciation of the collaboration from which the illustrative phase of production most frequently proceeds. It is the penciler who is most often credited as the producer of the graphic elements, at the expense of the inkers, letterers, and colorists, who are relegated by the vast majority of readers to the second-rate status of “helping hands,” whereas the professionals, for their part, know that the additive functions of lettering and coloring perform an important role in comic books. An example of this misunderstanding is presented at the beginning of the film Chasing Amy (1997) by Kevin Smith, himself a comic book writer who is very familiar with this world. The inker-colorist of a comic book on hand for a comic book signing is faced with a very indelicate comic book fan who, refusing to understand the specificity of inking, repeatedly argues that the inker does nothing more than trace the work of the penciler (“You’re just a tracer!”). The more that the graphic competence of a fan grows, the more he is able to refine his judgments about the drawn objects within a secondary hierarchy based on the appreciation of diverse combinations of pencilers and inkers, in which some are seen to raise the level of others (“Tom Palmer is always the best inker for Gene Colan,” “Curt Swan created his best Superman stories when he was inked by Murphy Anderson”) or the opposite (“Vince Colletta wrecked Jack Kirby’s pencils”).

Representation is not understood here as such: the evaluation of the contents in their entirety is in fact a judgment on the form that privileges the graphic conventions and inherent narratives of the formulas of superhero stories, but which equally confers an added value that is interpreted as a result of a superior quality of work. This is where the enthusiasm that is shared by a large number of readers for highly detailed graphic “realism,” provided it remains within the interior of the genre and enriches the representation of superheroic anatomy, radically (and, to the point of view of many external observers, ridiculously) out of proportion to the canons of academic art, originates.

In this sector, fans structure their interest from an interest in the past, or more exactly, from a present colored by the past. To this end, their forms of investment are pronouncedly different from those in the “commercial” sector, where the relationship is structured by a present colored by the future, with a taste for speculation and an affinity for new releases. In the “historical” sector on the other hand, comic books function secondarily as objects of consumption and exchange, and primarily as objects of memory. The diverse publications that can be placed in this quadrant show how comic books can serve to support the reconstitution of individual or collective histories of readers, or even the industry as a whole.

Under the direction of Roy Thomas, Alter Ego (since 1998) has taken up the mantle of the important fanzine that was previously published by Thomas and Jerry Bails. Its editorial stance, which reflects the tastes and history of fandom from the 1960s, shows a strong attraction to comic books published between the end of the Second World War and the dawning of the 1960s, that is, the Golden and Silver Ages, with very little reference to the speculative or commercial aspects of the hobby (which, historically, became an important aspect only at the end of the 1960s). This magazine exemplifies an almost pure form of “nostalgia,” where comic books occupy the center of a personal history because of the fan’s emotional investment in the content of comics, but also because of the social relations that these books helped the fan establish with other fans. Neither economic nor truly cultural, the relationship with comic books here is largely emotional, with judgments about taste largely shaped by personal histories.

Nostalgia takes on a more collective dimension in the magazines that concentrate on the history of the comic book industry, like Comic Book Marketplace (CBM) and Comic Book Artist. CBM has come a long way from its origins in 1991 as a monthly adzine analogous to the Comics Buyer’s Guide, having witnessed a spectacular transformation, becoming, in less than six months, a magazine offering information about collectors, collections, and collectible objects, but at the same articles on the history of comic books, older titles, characters, and authors. The cover of CBM frequently sported revealing subtitles: “The Magazine for Golden and Silver Age Collectibles” (#23, May 1995), “The Magazine for Golden and Silver Age Collectors” (#24, June 1995), “The Magazine for Advanced Comic Book Collectors” (#44, February 1997), “The Magazine for Golden Age, Silver Age, & Bronze Age Collectors” (#72, October 1999). What characterizes the collectors addressed by CBM (a group that should not be confused with the “speculators” catered to by Wizard) is the concept of legacy that drives the logic of their accumulation. This logic is found in the history of the comic book industry and its actors, where speculators are motivated by the anticipation of future economic values that are not related to judgments about the form. Their position within the field, midway between the economic and cultural poles, can be differentiated from the nostalgic position insofar as their investment largely exceeds their personal history insofar as it mixes scholarly and pecuniary interests. Within the comic book universe there are enlightened collectors who are in the market for art, erudite collectors whose collections reflect scholarship, and the opposite.

Comic Book Artist and Comic Art define this scholarly opposition by dis-associating their activity from collecting. Comic Book Artist (1998–2003)34 has become, over the course of several years, a periodical principally dedicated to the oral history of the comic book industry since the Silver Age, publishing interviews to illustrate the careers of various artists or publishers. The choice of themes touched upon by the magazine demonstrated an undeniable nostalgic disposition regarding the 1960s and 1970s in its first fourteen issues (without, however, touching upon the history of fandom, the specialty of Alter Ego), but it later diversified in order to offer special features on contemporary artists like Adam Hughes (#21, August 2002), Mike Mignola (#23, December 2002), and Alan Moore (#25, June 2003). Comic Book Artist, as its title suggests, rests on a conception of the historical canon of comic books where one approaches works through knowledge of the artists more so than through the content of the work, where the access to products is formed by the producers.

A further step was taken by Comic Art (launched in 2002). This magazine occupies an elevated position relative to the cultural pole of the schema. Its title, which draws an allusion to the work of Steven Becker in 1959, embraces an extremely broad conception of comics that includes forms of humorous drawing and illustration. Where other magazines use cover illustrations from popular comic books, Comic Art opts for illustrations that indicate an entirely different sensibility. Its first issue carried a cover drawing by Seth, a Canadian illustrator known for his interest in the cartoons published in large American magazines like the New Yorker. Its second issue carried on its cover a blowup of a cartoon produced by Jack Cole for the publisher Humorama in the 1950s. The third had a reproduction of a nineteenth-century illustration, and so on. Its presentation recalls art magazines: glossy stock, high-quality reproductions (from originals whenever possible), the inclusion in each issue of an unfastened insert containing a comic by a master of the form, ads for original art dealers, old and rare works, and for limited edition works and books published by independent presses. Thus, Comic Art is placed in the gap produced by other specialized publications, in an area where comics are made the object of institutional recognition as an integral aspect of American visual culture, but also at a place where the fan gives way to the connoisseur, to the aesthete capable of appreciating drawings that are removed by time and style from contemporary popular works. In opposition to the other three magazines occupying this sector, Comic Art does not place mainstream comic books at the center of its content but focuses on a more expansive notion of comics that, for example, renders strictly American categories like Golden and Silver Age abstract. The discourse adopted is more aesthetic than nostalgic; it gives voice to the expressive form beyond the world of North America and ultimately moves comics closer to its more noble parents, better formed and culturally recognized than drawing and illustration in its academic sense. The expressive form—comic art—finds here its greatest degree of cultural autonomy. Bracketing off the world of speculators and collectors, converting the nostalgic discourse into an aesthetic analysis, this magazine cultivates discourse affirming the highest degree of cultural legitimation of comics because, in its expanded conception of the form, the sector of mainstream comic books becomes nothing more than a representative type, not the central form as in the magazines already cited.

In this respect, Comic Art occupies a space analogous to the twice-yearly journal of John A. Lent, International Journal of Comic Art. In addition to the norms of university publishing, the magazine is distinguished from the preceding by a much more austere presentation, a much larger window on international production, and a multiplicity of critical approaches that can only be found in a scholarly publication. Gathering connoisseurs for whom an interest in comics is mediated by the intellectual discourses of the academy, International Journal of Comic Art proves to be located very close to the fourth sector.