BASIC OPTIONS STRATEGIES AND SPREAD TRADING METHODS

Buying long or short option positions is a powerful investment tool. If you are right in the timing and market direction, very few if any, investments in government-regulated trading vehicles can offer the same leverage and profitability with limited risk. The key to making money in any investment, first of all, is to be in the market and to establish a “position” before the market moves. Timing the entry or exit is most of the battle and having the right amount of positions “on” is the rest. Using seasonal analysis, as illustrated in the Almanac, may help in preparing you for specific trades.

There are two types of options: a call and a put. There are two kinds of positions: long is a buyer and short is a seller. A buyer or long option holder of a call has the right, not the obligation, to be long an underlying security or derivative product at a specific price level for a specific period of time and for a specific price called the “premium.” A buyer or long option holder of a put has the right, not the obligation, to be short a position for a specific price that is paid by the buyer at a specific price level and for a specific period of time.

For option buyers the “premium,” or option price, is a non-refundable payment. Premium values are subject to constant changes, as dictated by market conditions and other variables. A seller or option writer of a call or put grants the option buyer the rights conveyed from that option. Sellers have no rights to that specific option except that they receive the premium for the transaction. They are obligated to deliver the position as assigned according to the terms of the option.

A seller can cover his or her position by buying back the option or by spreading off the risk in other options or in the underlying market, if trading conditions permit. A buyer of an option has the right to either offset the long option or to “exercise” his option at any time during the life of the option. When an option is exercised, the buyer obtains the specific position (long for calls and short for puts) in the underlying market at the specific price level as determined by the strike price.

There are three major factors that determine an option’s value, otherwise known as the premium. One is the time value, which is the difference between the date you enter the option position and the date of expiration. The second variable in calculating an option’s worth is called intrinsic value. It is considered to be the distance between the strike price of the option and the price of the underlying product. If an “out-of-the-money” option’s strike price is closer to the underlying product price, it will be more expensive than an option that is further away. If an “in-the-money” option’s strike price is further from the underlying product price, it will be more expensive than an option that is closer.

The third factor is called the volatility rate. This is based on price fluctuations in the underlying market. There are other variables that are used to calculate an option’s value, like interest rates and demand for the options themselves. For instance, if you bought a call option and if the underlying market is moving up toward your strike price, then the option’s premium value may increase in value.

One of the first things to know about buying options is that you do not need to hold them until expiration. An option buyer may sell their position at any time during market hours when the contracts are trading on the exchange. Options may be exercised at any time before the expiration date during regular market hours by notifying your broker.

Usually one exercises “in-the-money” options. This is called the American style of option exercising. Under the European style of option exercising, you can exercise your option only on the day the option expires. The Black-Scholes math formula is used to calculate a theoretical value for an option using the current underlying market and other variables, such as expected volatility, time until expiration, interest rates, and the options strike price. The following are some terms, called the “Greeks,” which are used in calculating the different options values. They all have respective value references in the pricing of the value of an option.

Beta is a measure of an option’s price movement based on the overall movement of the option market.

Beta is a measure of an option’s price movement based on the overall movement of the option market.

Delta is the amount by which an option’s value will change in correlation to the change in the underlying contract.

Delta is the amount by which an option’s value will change in correlation to the change in the underlying contract.

Gamma is the rate of change in an option’s delta based on a certain percent change in the underlying contract.

Gamma is the rate of change in an option’s delta based on a certain percent change in the underlying contract.

Theta is the estimate of the price depreciation from time decay.

Theta is the estimate of the price depreciation from time decay.

Vega is the measure of the rate of change in an option’s theoretical value for a certain percentage change in the volatility rate.

Vega is the measure of the rate of change in an option’s theoretical value for a certain percentage change in the volatility rate.

There are other important calculations to consider as well. One is called implied volatility. This is a figure that is used to rank the volatility percentage that explains the current market price of an option. It is considered the common denominator of option pricing. Implied volatility helps compare an option’s theoretical value under different market conditions.

Another one is historical volatility. It refers to the measure of the actual price change of the product during a specified time period and is calculated by taking the annualized standard deviation of daily returns during a specific period of time.

There are many other variables to consider when trading in options. Here are a few strategies John likes to use on a directional trade.

Using a bullish seasonal study, if he expects the market to move within 10 to 30 days, he likes buying out-of-the-money calls with no less than a delta of +30 and with no less than 60 days until expiration. This allows him to participate in the market with limited risk due to the extra 30 days beyond the move’s expected time.

Using a bullish seasonal study, if he expects the market to move within 10 to 30 days, he likes buying out-of-the-money calls with no less than a delta of +30 and with no less than 60 days until expiration. This allows him to participate in the market with limited risk due to the extra 30 days beyond the move’s expected time.

On a bearish seasonal trade setup, he would buy an out-of-the-money put option with a delta of −30 and with no less than 60 days until expiration.

On a bearish seasonal trade setup, he would buy an out-of-the-money put option with a delta of −30 and with no less than 60 days until expiration.

A risk factor is the half-and-half rule; if half the time value or half the premium value erodes, reevaluate the position. Either get out of the option, or salvage some premium by liquidating a portion of your position.

A risk factor is the half-and-half rule; if half the time value or half the premium value erodes, reevaluate the position. Either get out of the option, or salvage some premium by liquidating a portion of your position.

In addition to commodity options, there are exchange traded notes (ETNs) and even leveraged exchange traded funds (ETFs) that are optionable. And now there are extensive weekly option expirations. We hope this explanation has expanded your trading knowledge and has helped you become aware of the many choices available to take advantage of the seasonal trades presented in the Almanac.

SPREAD TRADING METHODS

Unlike outright long or short positions, spread trading entails the simultaneous purchase and sale of at least two different securities at the same time. These products can be the same market for different delivery dates or they can be related, markets where one is looking for one of the transactions to outperform the other.

The reasons for executing a spread trade, in most cases, are that the exchange will give a trader margin relief and the risks are sometimes less in a spread trade than in an outright position in one market. However, not all spreads involve just one exchange and, therefore, do not qualify for margin relief. In addition, spread trading may require one to “leg” into one side at a time rather than a single order entry method.

The main purpose of a spread trade is to take advantage of the difference in price rather than the price direction of the markets individually. However, many spread trading opportunities do arise from applying seasonal analysis, especially in some of the markets covered in the Almanac.

Spread traders are looking for the price difference to widen or narrow depending on the strategy and position employed. For example, a bull spread refers to the purchase of a nearby contract and the sale of a deferred contract. In a bull spread, one is looking for the price scale difference to widen. The opposite is true for a bear spread. One would sell the nearby contract and buy the deferred contract, with the expected outcome of a narrowing or convergence of prices.

Spread trades are less volatile than other forms of trading, such as outright stock purchases or option trading. Even when trading a foreign currency or an outright futures position, one can expect less risk because the volatility is usually substantially reduced and that in turn decreases the margins requirements.

There are intra-market spreads (the same market but different delivery periods) and inter-market spreads (different but related markets). Some difficulties may arise in calculating the profit or loss in some inter-market spreads, as some commodities have different “tick” values. For instance, live cattle is $400.00 per 100 point move while feeder cattle is $500.00 per 100 point move. So traders need to make certain they are aware of these discrepancies.

One can trade two different wheat contracts at different exchanges, such as Kansas City Wheat versus Chicago Board of Trade (CME) Wheat. Most spread traders put a bull spread on the same commodity, which is buying the nearby date and selling the deferred.

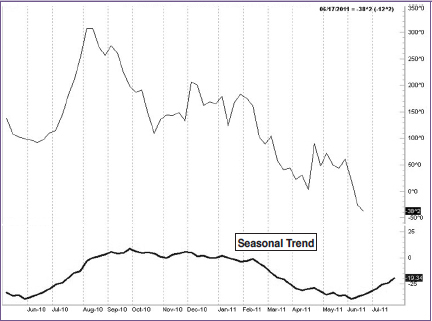

In Figure 1, we have the long October live cattle contract versus the short April live cattle contract. The graph highlights a seasonal low in June. Here is a spread opportunity one can employ from our top seasonal longer-term play in live cattle on page 60, which states: buy a single April live cattle contract on or about June 20th and exit on or about February 7th.

Figure 1: Live Cattle Long October/Short April Intra-Market Calendar Bull Spread

Chart courtesy TradeNavigator.com

Rather than buy a single cattle contract, one can take advantage of the bulk of the trend move and hold for less time by employing an intra-market spread trade, going long October cattle and, at the same time, selling the further out April contract. The hold time will be considerably less, as is shown in the bottom portion of the graph, where the peak period for this spread is late September through October.

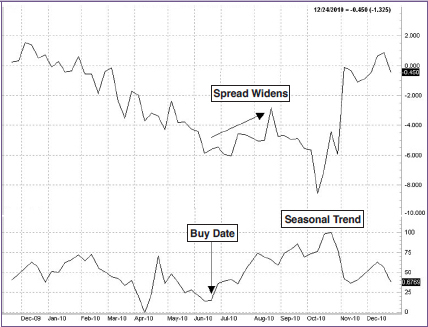

In Figure 2, we have a more typical inter-market spread of buying cattle and selling hogs. The seasonal study at the bottom of the price graph shows the tendency for cattle prices to appreciate more over the price of hogs from June through about November.

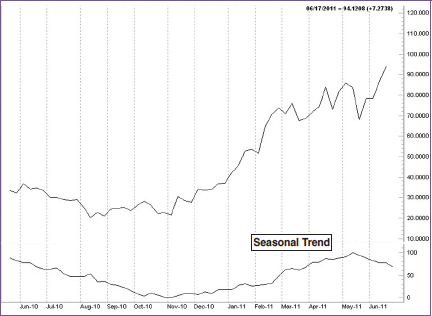

In Figure 3, is the popular inter-market wheat/corn spread. Typically wheat carries a premium over the price of corn, and the time to enter long positions in this spread is about mid-June.

Since most commodities tend to move in a strong trend direction over a period of time, spreads are useful trading strategies that allow the trader to participate in the trade without higher risks and excess capital. The energy complex has a few extremely useful spread trading opportunities. Besides trading an intra-commodity spread, such as buying a bull spread in crude oil futures ( buy the near then sell the deferred), another popular and useful spread is buying an inter-market spread, such as Light Sweet crude oil versus Brent. Then there is the ever popular “crack spread” in Figure 4. This is the energy spread that combines a short position in crude oil and the opposite direction in the by-products, such as RBOB gasoline and heating oil contracts.

Figure 4: Long Heating Oil/Long RBOB Gasoline/Short Crude Oil “Crack Spread”

Chart courtesy TradeNavigator.com

These are just a few spread trading concepts. but there are endless spread opportunities, such as in equity indexes like the S&P 500 versus the Russell or the S&P 500 versus NASDAQ, or in international index spreads like the DAX versus the Dow. Spread combinations also exist in foreign currencies, where there are great opportunities like the British pound versus the euro. We hope this helps shed light on other ways to take advantage of the seasonal analysis presented within these pages.