1987 to 1989

It’s summer. The days are soggy and long in Chapel Hill, and the University of North Carolina kids have gone home to wherever they’re from, leaving Franklin St. to revert to its native torpor. At night the bars are emptier, and the insects, emboldened by the heat and still air, are louder and more insistent.

It’s always summer with Merge. Aside from three crucial, bitter-cold days in the dead of a Minnesota winter, Merge’s story could almost be told in summers. It was conceived in the summer and born in summer; its birthdays, when it stands up in the kitchen doorway to have its height marked off in pencil, have always been celebrated late and long on summer nights at the Cat’s Cradle. So many of the songs that define Merge are hymns to summer, to staying up late and sweating and leaving the windows open. So many of the records are the kind, in the words of cofounder Laura Ballance, that you can spend a whole summer listening to.

The summer in question is the summer of 1987. Ronald Reagan has just nominated Robert Bork to the Supreme Court, and Guns ‘n’ Roses has released Appetite for Destruction. And Mac McCaughan, a scrawny, dreadlocked nineteen-year-old, has moved to Chapel Hill after deciding to take a year off from his studies at Columbia University. Mac had been raised in a genteel neighborhood in nearby Durham; his father, an attorney for Duke University, moved the family there from Florida when Mac was twelve. Mac had always been fanatical about music. At first it was Big Rock: AC/DC, the Who, Led Zeppelin, Molly Hatchet, the sort of bands who looked like little miniature animatronic figurines from the upper deck at your friendly neighborhood amphitheater. To Mac, they were like cartoons, or characters playing themselves in a movie. Then one day in his early teens, intrigued by a flyer he saw at his high school, he caught two local hardcore bands, the Ugly Americans and A Number of Things, at a coffeehouse. That was different. There was noise, and speed, and aggression, and slamdancing. He wasn’t sitting in a chair, apart from the band, admiring a lightshow. He was standing right in front of them.

He went to Schoolkids, a record store in Chapel Hill, and bought records by bands that he’d been hearing on the local college radio station and reading about in Rolling Stone: Hüsker Dü’s Zen Arcade, the Minutemen’s Double Nickels on the Dime, and Minor Threat’s Out of Step EP. He saw the Minutemen play in the basement of a church. They carried their own gear and sold their own T-shirts after the show. AC/DC was cool, but this was real.

Mac has a way of meeting the people he wants to meet. He eventually wound up playing guitar in A Number of Things. But before that, he started his own high school band, the Slushpuppies, with his friend Jonathan Neumann playing drums. Mac and Jonathan learned that they weren’t too bad at aping the sounds of all these new records that they loved.

When he went to Columbia in 1985, Mac papered his dorm-room wall with flyers and show posters. New York was great for seeing bands – Sonic Youth, the Damned, Mudhoney, Big Black, the Replacements – but lousy for being in one. There was no place to practice, no one to play with. You had to haul instruments around on the subway. He wanted to play with his friends, who’d stayed down South.

So in the summer of 1987, Mac took a year off and came home to live in a dingy rental house in Chapel Hill.

Laura Ballance lived in Chapel Hill, too. She had just finished her freshman year at UNC. Laura’s parents moved her around a lot as a kid; she was born in Charlotte, and had lived in Atlanta for a few years before spending her last year of high school in Raleigh. Laura was a goth girl – dark, painfully shy, a little bit lost, and prone to crippling self-doubt. She was also beautiful and, with her severe black makeup and combat boots, cut an intimidating figure on campus. She kind of scared people.

In Raleigh, Laura had fallen in with the hardcore crowd. One of the first concerts she ever went to was Bad Brains in Atlanta. She didn’t know anything about hardcore, and it was overwhelming and loud and frightening. She had to concentrate on breathing amid all the chaos and aggression. But she always felt like an outsider, and her friends were all outsiders, so she started hanging out at Atlanta’s Metroplex with skinheads and catching shows.

Raleigh and Chapel Hill are just a short drive apart, but they had very different scenes. Raleigh was dark, angry, and punk – more leather jackets and houses with spray paint on the walls. Chapel Hill was collegiate and hip. Laura was a Raleigh girl. She started dating Scott Williams, the lead singer of Days Of… , a hot-shit Raleigh punk band that was starting to graduate from the loud-fast-hard approach and incorporate a few of the angstridden adolescent tricks that later would come to be known as “emo.” Williams was a little bit older, and knew just about everybody in the Raleigh hardcore scene. When Black Flag came through town on tour, they crashed at Williams’s house on Ashe Avenue, known as the “Ashe-hole” for its rundown appearance and frequent parties.

L.A. and Washington, D.C., are usually credited as the prime generators of the do-it-yourself hardcore movement that proved to a generation of disaffected kids that making music, and records, was within their grasp. But Raleigh had its own roiling scene in the eighties, anchored by Corrosion of Conformity, a blazingly fast, angry-sounding band of high school kids founded in 1982. COC, like their inspirations Black Flag and Minor Threat, didn’t believe in waiting around for someone with money to tell them that it was okay for them to make records. And as Black Flag and Minor Threat sold their self-made EPs and 7-inches, so COC began to organize compilations of local hardcore bands, which they released on their own No Core label. They started touring on their own, just because they could.

Raleigh was home to an ever-shifting constellation of bands, usually sharing members, practice spaces, and even instruments, and COC served as an example to anyone who was paying attention that making noise wasn’t rocket science. Though their music was violent and dark, they made a habit of being inclusive and encouraging to anyone else who wanted to join in. They played at house parties or at dives, generating plenty of chances for lesser-known local hardcore bands to open the show and gain an audience. Drummer Reed Mullin’s parents had an office space in downtown Raleigh that was open to anyone who needed to use the copy machine to run off flyers for their show, or the telephone to make long-distance calls to clubs to set up a tour. Whenever a hardcore show was going on, he’d drive a circuit through Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill in his van, offering a ride to anyone who needed one. They didn’t just want to be in a band. They wanted to build a community.

By the mid-1980s, that community found itself growing up. Hardcore started to sound formulaic, and bands like R.E.M. and Sonic Youth demonstrated that the spirit of independence and casual rejection of mainstream tastes could be accomplished without tossing nuance and melody out the window. By 1986 or so, a legion of COC acolytes had begun to branch out. Stillborn Christians’ Jeb Bishop veered toward carnivalesque retropop with Angels of Epistemology, which included Sara Bell and Claire Ashby, high school classmates of Mullin. No Labels’ singer Wayne Taylor, whose hardcore credentials went all the way back to opening for the Dead Kennedys, picked up a bass guitar for the first time and started playing angular, unconventional pop in Wwax.

So it’s the summer of 1987. Mac and Laura both find themselves in Chapel Hill.

Claire Ashby (Angels of Epistemology and Portastatic; Superchunk merch girl)

The music scene was so small then. Raleigh was like Mayberry. The Raleigh and Chapel Hill and Durham people all knew each other.

Barbara Herring (Cofounder of Tannis Root productions, a Raleigh indie-rock T-shirt company) If there was a show of any kind, anywhere, around Chapel Hill or Raleigh, everybody went. All fifty people that were interested in that music.

Scott Williams (Days Of..., Garbageman, and -/-) But those fifty people wanted to be there. And those were the people that went on to be in the early Merge bands.

Jack McCook (Superchunk) When he came back to Chapel Hill, it was like “Mac’s back! Mac’s back!” That kind of thing. I thought, “Who is this little fucker?” You know?

Glenn Boothe (Former music director for UNC’s college station, WXYC; former A&R and radio promotion manager for Island Records, Sony, and Caroline Records; currently owns Chapel Hill club Local 506)

I met Mac one night at a party at my house, when he was literally rifling through my records. And I had this Buzzcocks record, this weird import, that he hadn’t seen. That was our first conversation.

Laura Cantrell (Bricks, host of WFMU’s “The Radio Thrift Shop,” singer/songwriter)

He seemed like a creature from another universe. A super-shaggy, long-haired, straightedge kid from North Carolina.

Kevin Collins (Subculture, Days Of…, and Erectus Monotone) He looked like a caveman.

Jim Wilbur (Superchunk) He had big dreadlocks. He’s always been a very cheerful, kind, outgoing, and smart guy. But I’ve got to say, when I first met him, the hair put me off. He was always messing with his four-track, and late at night, we’d make noise tapes. We had a band called Dust Buster, in which the main instrument was a dust buster. It was, like, high concept.

Mac Jonathan Neumann’s family lived on a farm on a gravel road between Chapel Hill and Durham. Since he had distant neighbors and parents that went out of town a lot, we could make lots of noise all weekend at any hour, and we did. In high school, a typical day out there would consist of playing music for a long time, drinking beer if we could find someone to buy us some, and then dancing

around the tiny living room to the Clash or the Violent Femmes or something like that.

Jonathan Neumann At first, we called ourselves Ranger Rick. It was silly. One of my most vivid recollections is playing “Jump” by Van Halen out in my yard. Just being ridiculous. “Smoke on the Water,” things like that. And this is all in the shadow of my chicken pen. We were completely terrorizing the chickens.

Mac Jonathan was at UNC that year while I was back, so we got the Slushpuppies going a little more seriously than we had in high school. We recorded some songs on my four-track at my parents’ house. We also recorded a bunch of stuff at Duck Kee in Raleigh.

Laura Duck Kee was run by a guy named Jerry Kee, and basically what Jerry did was turn his whole house into a recording studio. He’s like a little monk of recording. There’s still a sink and a refrigerator in the kitchen so that he can eat. But every corner of the house has recording gear and instruments in it. There’s cat hair everywhere. It’s not what comes to mind when you think “recording studio.” When Superchunk recorded there, I was always in the bathroom with my bass amp.

Mac My friend Lydia Ely at Columbia was from D.C., and used to work at Häagen-Dazs with Ian MacKaye and Henry Rollins. She introduced me to Ian. When Fugazi started up, in 1987, Ian called me to see about setting up a show in town. I called Frank Heath, who owns the Cat’s Cradle, and we figured out how to make it an all-ages show. It was Fugazi’s first show outside of D.C., and the Slushpuppies were going to open, and it was all very exciting. I drew up a bunch of flyers for the show featuring a photograph of some cows that I had taken. I was a little worried about how we were going to get people to come to this show by a band that no one had heard of yet, since they didn’t have a record out and had never played outside of D.C., so I put, in tiny letters underneath the name Fugazi: “Ex-Minor Threat.”

Ian MacKaye (Minor Threat and Fugazi; cofounder, Dischord Records) I was not happy. I really was not interested in selling Fugazi as anything other than Fugazi. It was just a pretty firm rule with us.

Mac I went around town and took down every flyer, made new ones, and posted them. I felt like the dumb kid that I was.

Jenny Toomey (Geek, Tsunami; cofounder of Simple Machines Records and the Future of Music Coalition) The first time I ever saw Mac play was in the Slushpuppies at a club in D.C. called d.c. space. I think I went because Ian probably was going. They had this great song that was basically Mac singing, “Let me count the ways I love you,” but in this totally punk-rock way. It was so incongruous: This very twee sentiment and this very punk sound. It’s been mined quite a bit since that time, but it was fresh as a daisy for me. I bought a Slushpuppies tape from him.

Josh Phillips (Bricks) Actually, she gave Mac money for a tape, but he never sent it to her. The next year, I went to Columbia and she said, “If you see Mac ask him where my damn tape is.”

Mac had also begun playing guitar in Wwax, with Wayne Taylor and drummer Brian Walsby.

Wayne Taylor (No Labels, Wwax; unsuccessful 1993 mayoral candidate in Raleigh) I had wanted to release a Wwax single. And me and Mac and Brian were going to do it by ourselves. And at one point we realized, it would be much more economical – and more important – to involve everyone that we were playing with. And there were all these other bands, and we just tossed the idea around a little bit, and then we were doing it.

Mac We just got this idea that we were going to put out a collection of 7-inches from all the bands we were playing with around town that year. It was kind of a gimmick, almost – this ludicrously ambitious thing. The ridiculousness of putting out a box of singles by five bands no one had ever heard of was part of the charm of it. Wayne came up with the name evil i do not to nod i live. Which, in case you missed it, is a palindrome.

Flyer by Mac for Fugazi’s first North Carolina show, and third show ever.

Sara Bell (Angels of Epistemology, Shark Quest) They just said, “We’re going to do this. We can make records.” They just started rounding up the bands. And it was such a cool, weird collection. There was the Black Girls, which had a very unusual, folky sound. And then the Angels of Epistemology, which didn’t fit into any category of anybody’s. And Wwax, and Egg, and Slushpuppies. It was really an eclectic combination of things. And that’s what it was like then. There would just be very different bands coming together, because there was no other place for them to be. So you didn’t have to adhere to any kind of genre.

Mac Wayne really made it happen. He found a place to press records, and he knew the people at Barefoot Press for the printing. Our slogan was, “5 bands, 13 songs, 14 people.” There were five 7-inches in these little boxes, with a cool booklet of art by all the bands. And we knew it could be done, because places like SST and Dischord had done it.

Andrew Webster (Bricks, Tsunami) It was kind of like trade secrets passed down. You know what? It’s not that tricky to put out a fucking record. You’ve got to call the pressing plant, you’ve got to have the master shipped to them. They make a plate, they press some records, they ship them back to you, you have someone design the cover, and then you put them all together by hand. Put them in a plastic bag and suddenly you have a record. Growing up, that always seemed like a magical process. But people started opening the door onto that sausage-making machine.

Ian MacKaye We set up a model at Dischord. I mean, the way we figured out how to make a 7-inch sleeve is that we took a British picture sleeve, pulled it apart, and looked at how it was constructed. And we literally just traced the outline of that on an 11 by 14 piece of paper and put our own graphics on the outline, and took it to a print shop and said can you make 1,000 of these? And then we cut them with scissors, and folded and glued them all by hand. We did that for the first 10,000 records at Dischord.

Wayne Taylor I just basically worked up an estimate, and figured out the budget for the pressing and the boxes and the printing. We all pitched in. I think it was like $2,000 total. The boxes were cases for quarter-inch reel-to-reel tape. I would see them in the studio, and one day I realized – you, know, that fits a 7-inch.

Mac We bought the boxes blank and screenprinted them by hand at our house. I remember laying like six boxes down at a time and doing a pass with the squeegee. We made a thousand copies and booked release shows in February 1988 where all five bands played in Chapel Hill at the Cat’s Cradle and the Brewery in Raleigh, and both shows sold out. It wasn’t just our friends in the audience at those shows. People wanted to see it.

Frank Heath (Owner, Cat’s Cradle) It was so impressive. You could tell that there was a lot of thought put into it, and that they grasped the concept of generating excitement by having a crowd.

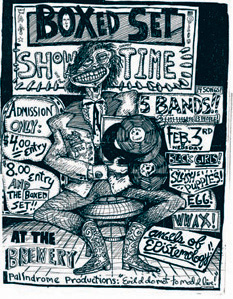

Flyer for evil i do not... release show at the Brewery in Raleigh, February 1988.

Front cover of the evil i do not... box.

Back cover of the evil i do not... box.

Mac It got local press. It was a big deal that strange-sounding local bands – Slushpuppies were probably the most “normal” of the bunch – could get people’s attention like that. Today, the writers for the Independent Weekly in Chapel Hill are young, they’re bloggers, they’re looking for cool stuff to write about. Back then, the music coverage was likely to be a review of a Bruce Hornsby concert or something. I think the “adults” were surprised that something like this could be put together basically under everyone’s radar.

Glenn Boothe It kind of showed, like fuck, anybody could do this. You don’t have to have a label, you don’t have to have a lot of money, you just get your friends together and record some songs and make it.

Wayne Taylor It was a bunch of creative people hanging around together who got some shit done.

Mac and Laura had seen each other around at shows, but they first got to know each other when they both got jobs at Pepper’s Pizza on Franklin St. in Chapel Hill.

Norwood Cheek (Filmmaker and video director for Superchunk, Squirrel Nut Zippers, Ben Folds) My friends and I called Laura “Death Chick.” She looked like a classic goth chick. But she was beautiful, and just so cool. I grew up in a small town in North Carolina, and that’s the kind of girl you dream of going to school with. It’s straight out of the movies. Oh man.

Jim Wilbur Everybody was in love with her. And she could give you the 500-yard stare and look right through you. But she also liked horses. The black hair and the clothes, that’s sort of a barricade between who you are and the rest of the world. And it’s indicative of a personality that’s vulnerable and sweet.

Lane Wurster (Former creative director for Mammoth Records; brother of Superchunk drummer Jon Wurster) Laura’s laundry day was like, “Is today a gray load or a black load?” You know, not a lot of color. Not really much for small talk.

Laura at Pepper’s Pizza, 1987.

Mac Pepper’s was basically selling pizza to the drunk frat boys. Laura was pretty good at projecting an air of, like, Don’t try to talk to me, punk. Which I think some of the drunk frat boys took as more of a challenge.

Laura Mac and this other guy that worked there, Matthew, made me cry because they were talking trash about Scott.

Mac It was just because I wanted to go out with her.

Amy Saaed (Former roommate of Laura’s) I liked Scott Williams. I thought he was hilarious. Also I knew how hard Mac was trying and scheming.

Scott Williams This is going to sound really stupid, and I know I sound stupid saying it. But I was the king of the scene at the time. Amy Saaed I always made the joke that Scott was king of the Raleigh scene, and then Mac became king of the Chapel Hill scene. That was my little joke.

Scott Williams That was it. Feuding kingdoms. A feudal war.

Kevin Collins Raleigh was the other side of the tracks. The kids who couldn’t get it together. Around that time, like 1986 and ‘87, in the hardcore scene, people were starting to get into this other, Sonic Youth–type stuff, and all the punks were growing out their hair. And I think Mac kind of came from that.

Ian MacKaye Chapel Hill is such a college town. It was like a slightly defanged hardcore. It was still unique, but it was coming from a less angry place.

Scott Williams Raleigh was this blue-collar, or no-collar, rock scene. We were all about partying, and rock, and fuck tomorrow. And in Chapel Hill, they had come from a wealthier background, gone to great colleges, and knew there was a tomorrow. And knew where to invest in that tomorrow. We didn’t see tomorrow.

Mac So with the Slushpuppies, every bass player that we’d ever played with was insane. They were all over the place and just really into overplaying. So I thought, Great! We’ll get someone who doesn’t know how to play bass, and there’s no way she could be doing bass solos the whole time. So I asked Laura to learn how to play bass.

Laura I felt like I was pushed into it. Music was important to me, but I had never wanted to actually play music or be on a stage. The idea petrified me. I was mystified by Mac and his friends’ knowledge of all these obscure punk-rock bands. They were punk-rock scientists. It makes sense that, living in a small town, they really devoured zines like Maximum Rocknroll, and internalized all the information. They had to dig to find all this music; in Atlanta it was all right there and easy to access.

Jim Wilbur I don’t think they would’ve ever been together without the band. I think they got together because Mac was like, “I’m going to teach you how to play bass. And we’re going to start a band. And from there, I’m going to start dating you.”

Mac That was probably the motivating factor. But it was also like – “Well, I spend all my time making noise and playing in bands, so Laura should spend all her time doing the same thing!” In my narrow view of the world, it was like, “Why wouldn’t someone want to be in a band?” That sounds fun, doesn’t it? We called it Quit Shovin’. It just seemed like something fun to do.

Amy Saaed Laura and I lived in an apartment with six people, and we had a roommate named Sue Hunter. And Mac was actually supposed to be teaching Sue to play bass. And I came home one day, and he was teaching Laura how to play bass. Mac’s a smart man. He knows what he wants, and he goes and gets it. He had his little plan all ready.

Jim Wilbur He basically stole her from Scott Williams. And I was always like, “Mac, you are in deep, deep trouble.” And he was like, “I know, they’re going to find me in an alley with a bullet in my head and Scott Williams’s name on it.”

Scott Williams I was going through a bad period in my life. My band was breaking up, I got kicked out of my house. It seemed like everything was falling apart at the same time.

Wayne Taylor Mac and Laura were a unit, and it was obvious. They were headstrong to be in love and the world was their oyster.

Amy Saaed In the beginning, Mac just had stars in his eyes. Laura could do no wrong. Not that Laura really did wrong.

Jonathan Neumann Quit Shovin’ was me, Mac, and Laura. I was playing guitar, he was playing drums, and Laura was playing bass. It was to make Laura more comfortable playing bass – we were all new on our instruments, so we’re all on the same skill level. Mac was very encouraging that way. It didn’t go very far. We had ten or so songs. We played at one party. Redd Kross was in town, and they came. Which was a little nerve-wracking.

Quit Shovin’, a.k.a. Rodeo Clam, at a house party. Left to right: Jonathan Neumann, Mac, Laura.

Lane Wurster I literally remember Mac showing Laura where to put her fingers, onstage. I didn’t really get it.

Laura I was terrified the first time we played. And messing up a lot. I don’t remember a whole lot about it – and not because I was drunk. My brain would seriously seize up in these situations. Yeah, I remember it being really bad.

Jonathan Neumann Laura was kind of a reluctant partner. I know she enjoyed playing and everything, but I remember her being sort of conflicted about being in music. Mac was pretty persuasive. Cajoling. And I don’t mean that in a negative way.

Laura I think about myself back then, and I wasn’t very in charge of my own life. I was kind of going through life not wanting to hurt anyone else’s feelings, and being kind of easily manipulated, you know? This is not really very flattering to myself, I know. Honestly, I did not want to get onstage. It was never a fantasy of mine.

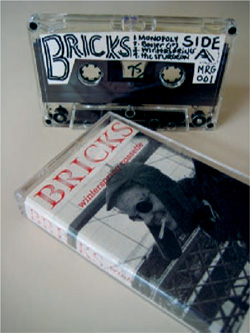

Merge Records’ first release: Winterspring by Bricks.

Mac After Quit Shovin’ we also had Metal Pitcher, which was me and Laura and Jeb Bishop. We practiced in COC’s practice space. And we just decided, “We’re going to exist and we’re going to make a record. Why not make a record?” So we recorded some songs on a four-track in a basement somewhere, and that ended up being the first Merge 7-inch – “A Careful Workman Is the Best Safety Device.”

Wendy Moore (Former roommate of Laura’s) There was a house party in Carrboro where Metal Pitcher played. Laura was very tentative. She was just learning the bass at that point, and that was kind of clear. But still, it was a lot of fun. I think Mac just begged and pleaded for her to play. “C’mon, it’ll be great!” And he’s got so much charisma that you can’t help but go along with it. He’s really inclusive to people he cares about. And that was who he cared about.

Mac I went back to Columbia after my year off. During my junior year, in 1988, I started Bricks with my roommate, Andrew Webster, and myself, recording on my four-track in my bedroom in our apartment on 108th Street. It was tiny and overcrowded – someone had to sleep in the living room all the time. We recorded what would become the Winter-spring cassette, Merge’s first release, in that apartment. One night, I was sitting in my room recording with headphones on, and I heard what sounded like a gunshot in the alley. I hit the floor. It was fucking loud. Turns out some kindly neighbor had tossed a brick through our window. That’s how Bricks got its name.

Andrew Webster We didn’t really have space for a drum kit, so we played with Tupperware containers filled with rice, or cranberry juice bottles that we’d drained, and banged on with sticks and whatever we could find. We eventually added Laura Cantrell and Josh Phillips. We’d heard that Josh was taking drum lessons, and we didn’t realize that he wasn’t quite far enough along to be the whole rhythm section of the band. So we added Laura as an additional percussionist. She had the great benefit of being a good singer as well.

Josh Phillips I’m pretty sure that I have the privilege of being the absolute worst musician that Mac has ever played with in his life. I literally couldn’t keep the beat. And instead of just kicking me out of the band, they brought in Laura Cantrell to try and get me on beat, and have two drummers. I thought that was really nice.

Mac I always had the impression that Laura was slumming it a bit being in Bricks. She could actually sing, compared to us, and she was just more of a serious person, so I felt lucky that she agreed to come over and mess around with us goofballs and our goofy songs.

Laura Cantrell I joked with Mac at one point that I had secretly tried to turn Bricks into my country band. I suggested a Doug Sahm song or something for us to cover. And Mac said, “I don’t think that’s quite the direction we’re going with this, Laura. Here’s our new song, ‘Smoking Hooch with the Flume Dude.’”

Brandon Holley (College roommate of Mac’s; former editor of Jane magazine) The songs were all written about our life in the apartment, and what was going on. The rehearsals were in our living room. It was kind of like an extension of making dinner.

Josh Phillips One of us was studying the history of Albania. So we did an Albanian Christmas record, and all the songs on it had to be about Albania, and also about Christmas. The big hit from that tape was this thing called “Don’t Hog the Nog, Zog.” Apparently, in Albania there actually was a King Zog. We played with Fugazi once, and it was ridiculous. There’s 350 rabid Fugazi fans, you know, and we’re singing about the girl with the carrot skin.

Mac In the summer of 1989, between my junior and senior year, Laura [Ballance] and I drove across country to take some friends who had graduated back to the West Coast. We were headed to Seattle, where our friend Aubrey Summers knew Bruce Pavitt and Jon Poneman, who had started Sub Pop the year before, and we were hoping to catch a Mudhoney show while we were out there.

Jason McLachlan (College friend of Mac’s) Mac had his dad’s van, which had two twenty-gallon fuel tanks that were linked, so you could go forever without stopping for gas. And they had set it up with an eight-track tape deck and Laura had figured out how to record on to eight-track tapes, so we had this box of punk-rock music on eight-track.

Josh Phillips We tried to go to the Grand Canyon, but we got there at two a.m. and everything was closed, so we left. And when you leave the Grand Canyon at night, there are hundreds of rabbits in the road. Aubrey was driving. At first she was swerving and going slow, but we had sixty miles to go to get to a hotel, and at a certain point she was just like, “Fuck it.” It was just badump, badump, badump. We ran over literally hundreds of rabbits.

Bricks at CBGB’s Record Canteen, 1990: Laura Cantrell, Josh Phillips, Andrew Webster.

Mac’s parents’ van after catching fire in New Mexico in 1989.

Laura We were in the middle of New Mexico, and had spent the day driving to see the Anasazi ruins at Chaco Canyon, on these gravel roads for miles. We were on our way back, and were about to get back on the highway, when smoke started coming through the air-conditioning vent.

Mac And then flames started shooting out from under the steering column.

Laura I put the van in park, put on the emergency brake so it wouldn’t roll into the brush and start a brushfire, turned it off, and jumped out. And then the van turned back on! By itself. It was like Christine. I jumped back in to try and turn it back off, but couldn’t, since the key was already in the off position.

Jason McLachlan We were trying to get our hands in there to pop the hood – Mac had a fire extinguisher – but it was too hot.

Laura We managed to get all our stuff out except all my eight-track tapes. And my favorite pillow. We were on an Indian reservation, next to some sort of general store, which was closed. And I remember when we hopped out, I realized things were bad when I saw the side reflector just melting off.

Mac We just sat there and watched it. The tires exploded.

Josh Phillips Mac and Laura just kind of went off over by themselves, and then Mac came back crying, just to look at it again, and then ran away again to be comforted.

Laura By the end, the windshield was draped over the steering column. Somebody called the fire department. We were so far from civilization that it took hours for them to show up.

Mac I called my parents and they rented a car for us, and we shipped a bunch of stuff home. And we piled into the Taurus, or whatever it was. When we got to Seattle, Aubrey took us to meet Bruce and Jonathan, and we got to go see their office.

Aubrey Summers It just seemed like one of the best tourist things I could take them to. It was definitely bustling. Lots of people running around in their band gear – their nighttime clothes, it looked like. Lots of makeup. I don’t think Mac and Laura were blown away. It was more like, “Okay. I could see doing this.”

Mac It was the week that the Mudhoney single “You Got It (Keep It Outta My Face)” came out. So we got copies of that, and Bruce got us into the first Sub Pop Lamefest, which had Mudhoney and Nirvana was opening. We already were fans of Sub Pop, so it was cool to be able to see that. We dropped everybody off and then it was just Laura and me on the way back to North Carolina.

Laura And that’s when Merge started.

Mac We were talking about all these recordings we had – I’d done a bunch of Bricks recordings on four-track, and Wwax had some stuff, and we had done the Metal Pitcher stuff. And we had already done the box set, so we saw how it could be done.

Laura The label was totally Mac’s idea. To call it “Merge” was my idea. We were driving through Colorado, and I started reading road signs while I was thinking about a name for it. I actually thought it was a pretty dumb name for a long time. But it’s certainly better than “Pronghorn Antelope,” which is another thing I saw while I was driving on that trip.

Jonathan Neumann Here’s the thing – Mac lived and breathed music. This was his life. When I went to visit him in New York for spring break, I mean, sometimes it was insufferable. I had to go from fucking record store to record store while he looked for the reissue of this, or that. Looking for the early punk rock records, you know, the seventies stuff. These folks that scrapped it, and did it a lot on their own.

Mac People ask the question a lot: Why did you decide to put out your own records? But it’s not like there was anyone else asking to put them out.

Wendy Moore When they started Merge, it didn’t seem like they were starting much of anything. It just seemed like an art project. They would give singles to the record stores, and they would get bought up. At the beginning it was teeny, you know?

Jenny Toomey There’s a great line in a Destroyer song: “Formative years wasted / In love with our peers, we tasted / life with the stars.” I couldn’t have found language that was more clear about that whole idea of what we were doing. The twenty people who understand what you’re talking about are the twenty most important people in the world. Maybe that’s the difference between professional culture and outsider culture. Our antennae were tuned very specifically for like minds, as opposed to sending out a signal to convert people. There are some kinds of art that are trying to find their peers, and there are other kinds that are trying to make peers.

Laura It was a lark. I had no idea it would last this long.

Mac Everything we knew how to do, we just knew how to do from the box set. But also because we were consumers of music. I read a lot of fanzines, so I knew where there was a place to take out an ad, or where to send a copy for a review. I eventually started working for Schoolkids, so then I was on the phone talking to Dutch East India, buying albums from them. Well, there’s a distributor. Let’s just use them. Revolver and all these other distributors – how hard could it be? I’m buying stuff from them at Schoolkids, why can’t they sell our stuff at other stores? Merge was in Laura’s bedroom at first, until she moved to an apartment where we had a separate room for it. Every six months or so – however often we were putting out the singles – we’d have a single-stuffing party. Get the singles, get the sleeves printed at Barefoot Press, order plastic bags to hold the sleeves, and go through repetitive motions.

Wendy Moore Laura had a loft with a bed on top, and a desk underneath. There were boxes of singles in her room, boxes of T-shirts. A little money box.

Amy Ruth Buchanan (Former roommate of Laura’s) We had a little tiny room devoted to Merge. And it had this little red table, and like some stacks of singles. No windows. It was just this little, tiny, closet-y kind of room. And Laura would work away.

Mac We would borrow money. Like a few hundred dollars from one person, and then do a release and then pay them back. Lydia Ely lent us money for the Chunk 7-inch. Glenn Boothe paid for the Angels of Epistemology 7-inch. My dad lent us the money for the Metal Pitcher single. So it was piecemeal – borrow money, pay it back, borrow money, pay it back. We did a Wwax double 7-inch that I helped fund with $2,000 that I got as a graduation gift from my grandparents. We were making enough to pay people back, and then we’d just sock away whatever else we made – $50, $100, so we wouldn’t have to borrow as much next time.

Ralph McCaughan (Mac’s father) Mac’s mother and I were “executive producers” on some records. But we were well-compensated: We got free records.

Amy Ruth Buchanan I remember one single-stuffing party, and Mac brought over a VHS tape of Seinfeld, which none of us had seen. It must have been the first season. We sat and watched those episodes while we stuffed singles, and thought it was howlingly funny. But it was perfectly in tune with Mac’s sense of humor, actually. Isn’t that such a counterculture thing to do? Watch Seinfeld?

Laura Mac went back to school for another year in the fall of 1989, and I ran the label pretty much by myself, except when he’d come back for breaks. I was also still in school, and working at Pepper’s and then Kinko’s. At first, calling distributors to try and get them to buy singles made me really nervous. But after a while, I developed relationships with them, and it was fun. But I also had to harass people to collect payment. Not so fun. There are also hazards associated with having a record label in your bedroom. The tape gun nearly killed me a few times.

Mac When a record would be done, Laura would send it up to me at school. I remember taking one to Pier Platters – taking the PATH train out to Hoboken, and saying, “Hey, I don’t know, you might want to buy some of this 7-inch.” And they were all these cool, beautiful girls who worked at Pier Platters who I was scared of. But it turns out they’re like, Sure, we’ll take sixty. Even if they’d never sold them it would’ve been cool because Pier Platters has our record on the shelves next to a Melvins single.

Kevin Collins It was pretty easy to play shows, and Jerry Kee’s place was cheap and right around the corner. People played in bands, and Mac would see them. And he’d say, “Can I put out your record?”

Typical Merge 7-inch-sleeve-stuffing affair, 1994.

Left to right: Colin Dodd, Laura, Joe Ventura.