Matt Suggs, Butterglory, and White Whale

My gripe of the month: People calling about their demo tapes. Please. What are you thinking? If we were floored by your demo tape obviously we would call you. I’m afraid to answer my phone anymore. I hate to tell people that I don’t like their music (or admit that I’ve had their tape for the last six months and still haven’t listened to it). So maybe I have a problem of being overprotective of people’s feelings, but I’d like to work on it at my own speed. So. On that positive, uplifting note, I end. Thanks for being there. LAURA.

— from Merge’s August 1992 newsletter.

In 1992, Mac and Laura popped in a cassette they had received from a band called Butterglory.

It would become the first unsolicited submission that Merge ever released, and it would launch a fifteen-year, seven-record relationship with Matt Suggs. Not very many people know who Matt Suggs is. He never sold a substantial amount of records. While Butterglory enjoyed a brief period of low-grade indie-rock cachet, they broke up before they could find a wide audience. Unlike many bands on the label, Suggs never attracted next-big-thing buzz. He never affected the look of the indie-rock antihero. But Suggs writes aching, clever, and timeless songs, and Merge has always put them out.

Laura Matt’s records are prime examples of how you can put out the best record in the world, and it doesn’t mean shit. If the timing is wrong, or the right people don’t notice it – I cannot explain what makes a record happen big. Not that it matters. I love putting out good records. And I don’t care if it sells 500 copies or 250,000.

Suggs was raised in Visalia, Calif., a small agricultural community between Fresno and Bakersfield in California’s central valley – a red county in a blue state. He has a self-deprecating wit, a laid-back, California attitude, and a nervous suspicion of mainstream culture, honed during years making music in his bedroom that few, if any, of his neighbors would care for or understand. There wasn’t much of a Visalia scene.

Matt Suggs It was pretty isolated. I was pretty much just discovering all these bands – Hüsker Dü, the Replacements, Dinosaur, Sonic Youth – through the fanzine networks. None of my friends really listened to what I listened to. I would save up money whenever I was going to San Francisco or L.A., to go to record stores. And when I’d finally get a chance to see these records I’d read about, it was like seeing celebrities – “Oh, this is the record I’ve read about for the last year, and now I’m seeing it in person.”

When Suggs was fifteen, he started recording songs in his room on a four-track cassette recorder.

Matt Suggs That was really critical, especially when you’re a loner who doesn’t have a band to work with. It was so hard to find people to play with, and the four-track became that person.

In 1990, Suggs met Debby Vander Wall at a community college in Visalia. They started dating, and Suggs recruited her into playing a rickety drum kit he had. Initially, it was just the two of them, making four-track tapes. They called themselves Butterglory, and played the occasional house party when they could find someone to fill in on bass, but it was mainly a recording project.

Matt Suggs It was just these little homemade tapes. We made little potato-print covers with handmade-looking stuff and just ran off maybe fifty of each to hand out to friends. It wasn’t like we were trying to even be a real band.

Four-tracks had been around since the late 1970s, and Bruce Springsteen famously recorded Nebraska on one in 1982. But the early nineties saw a flourishing cassette culture, based on bedroom noodlers who dubbed copies of their output with mocked-up covers to mimic “real” releases. Small-scale labels and distributors – like Chicago’s Ajax Records, which published a catalog of cassette releases with capsule reviews that readers could order from, and Dennis Callaci’s Shrimper, which sold cassette-only releases from Nothing Painted Blue and the Mountain Goats – sprung up to meet the demand.

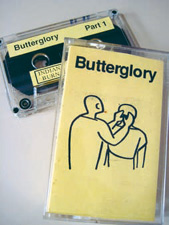

An early self-released Butterglory cassette.

Matt and Debby were happy just making cool-looking tapes – the designs were simple, with block lettering and stark line drawings – for their friends, but they occasionally sent out copies just to see what would happen.

Matt Suggs We sent a few out to labels and stuff, more or less just to get some acknowledgement, because we felt so isolated. If I just got the letter back on label letterhead saying, “Thanks for sending the tape,” that would be enough.

Matt had read about, and bought, Superchunk’s “Cool” 7-inch, but he had never seen the band, and knew next to nothing about Merge aside from the occasional reference to their early releases he’d seen in zines.

Matt Suggs I had bought these padded envelopes that came in a package of three. And I was sending a tape to Ajax, and a tape to K Records. And so I had this third envelope. And it was like, “Oh, let’s just send it to Merge.” I didn’t even put down a phone number or anything.

Mac I’d never heard of them, and it kind of reminded me of Pavement a little bit. But the more I listened to it, I thought the songs were really there, and catchy.

Mac wrote Suggs and Vander Wall a letter saying Merge would like to put out a 7-inch with a couple of the tape’s dozen or so songs. In the interim, Matt and Debby had decided to leave Visalia for Lawrence, Kansas, a college town that was capable of supporting a music scene.

Matt Suggs I got it literally the day before Debby and I were leaving to move to Kansas. I thought my friends were playing a prank on me, like it was a plot to keep us from moving. I had to check the postmark on the envelope. It actually came from North Carolina.

Matt and Debby drove from Lawrence to Columbia, Mo., to discuss the details with Mac and Laura a few weeks later, when Superchunk came through town. One day in the fall of 1992, a UPS deliveryman knocked on Suggs’s door in Lawrence with a box of 100 copies of the “Alexander Bends” 7-inch.

Matt Suggs I’ll never know how that feels again. You open the box and pull a record out, and you just can’t believe it. And you turn it over, and the Merge logo is on the back. I was beside myself. And I played it. Even though I knew all the songs. I put the needle on and listened to it. Well, it’s on there. Wow.

“Alexander Bends” is a defining document of the lo-fi recording movement. The songs were built around simple, repetitive, almost childlike guitar lines, undergirded by Vander Wall’s hesitant drumming. The pair traded vocals on the record’s five songs, and their laconic, unpolished voices lent the record a sense that the whole thing was on the verge of falling apart. Rendered through the depredations of a four-track, Butterglory sounded like a wind-up toy – a plinking, wheezing, pop contraption.

“Alexander Bends” was well received by several zines, and sold out of its 1,500-copy pressing within a year. In April 1993, Superchunk was playing in Lawrence with Rocket From the Crypt, and Mac and Laura asked Butterglory to open.

Matt Suggs I thought, “Oh shit, we don’t even have a band.” We’ve come out of the bedroom, and we have to get our shit together. A friend of ours who was living on the West Coast came out to play bass. We practiced a few times. It was a well-attended show, because of Superchunk. And it was the first time we played what I’d call a real show – a real stage with a real sound system. I had to get drunk the whole day, pretty much.

It was a strategy Mac and Laura would use repeatedly to help build the label – asking their lesser-known bands to open for Superchunk.

Butterglory followed “Alexander Bends” with another four-tracked 7-inch, “Our Heads,” one year later. In 1993, Suggs dropped out of school – “always a good idea,” he says – to take Butterglory on tour.

Matt Suggs It was intimidating. I had never been to New York before. And I remember thinking, “Oh, God, we have to drive into Manhattan! That’s going to be fucking freaky! Where are we going to park?” We played a show in Chapel Hill in 1993 that was one of our first out-of-town shows. Mac actually played second guitar with us. I was real nervous, because I still hadn’t played on stage that much. And it was awkward, because no one was standing for us. They were all sitting Indian-style. All of a sudden, this dude starts heckling me like crazy. I look over, and it’s Jim Wilbur. I wanted to shrivel up.

Jim Wilbur All I said was something like “Hey, why don’t you play the slow one from the good record!” That was a standard heckle from the Wet Behind the Ears tour.

Matt Suggs We camped out a lot on that first tour. We’d just play a show and then put up a tent somewhere. It was only like $10 a night. You could not convince me to do that again.

In 1994, Butterglory decided to leave the four-track behind and make its first studio record. The cost of recording the 7-inches had been zero dollars, but if Butterglory were to go into a studio, they would need an advance. Mac and Laura refused to use contracts with its artists, insisting that all deals be based on a handshake.

Matt Suggs It was just an agreement kind of thing. They’re friends of mine – people I would invite over to my house. So it was, “Hey, let’s do another one! Let’s do this, let’s do that.” We had done two 7-inches, and weren’t going to just continue doing 7-inches. We wanted to do an album. I don’t know what else we were supposed to do. It was all really casual.

Laura We weren’t thinking of it as a business, we were thinking about it as this fun, cool thing. Contracts seemed like a gesture of mistrust. We were putting out records by people we knew and were friends with, and that could trust us and that we could trust. We’d talk about the basic premise, and that was that. In hindsight, I think that was really naïve. But at first, there really wasn’t that much money involved, so it didn’t really seem to matter.

Brian McPherson (Attorney for Merge and Superchunk) I always thought it was a bad idea. I wrote a book called Get It In Writing. But that’s obviously their way.

Merge gave Suggs and Vander Wall a small advance, and Butterglory went into the studio to record Crumble.

Matt Suggs I was really scared of having big sounds on anything. We were really going for this rickety drum sound, and buzzing little guitar. I was worried that it would sound too produced.

Crumble, and even more so its unforgettable follow-up, 1996’s Are You Building a Temple in Heaven?, did sound produced. And the production – crisp drums, gorgeously fuzzed-out guitar drones, anachronistic keyboards, and the addition of bass player Stephen Naron as a permanent band member – liberated the songs. No more was Butterglory a quaint shambles – they were a tight and taut, slightly Anglicized pop band, with Suggs’s sedated vocals overlaid against Velvet Underground vamps. Temple opened with “She Clicks the Sticks,” a duet that narrated the band’s dissatisfaction with itself, with Suggs and Vander Wall alternating lines: “She clicks the sticks and hits the drums / This song is such a bore / As the guitar player’s amplifier hums / It’s all been done before.”

Matt Suggs I guess we kind of abandoned the lo-fi roots and accepted the speedy allure, to the alienation of some of our fans. A lot of them were into the lo-fi arty thing. But we were just working within the technology we had at our disposal at the time. It was because we couldn’t afford the thirty dollars per fucking hour! And you can only get so much fidelity out of a little fucking tape machine.

Crumble and Temple each sold about 5,000 copies. They were well received, with write-ups in Spin and Magnet. At the time, Suggs was working a food-service job at the local college cafeteria.

Matt Suggs The records would help out. And we’d go on tour for a month, come back with maybe $700 apiece. But it wasn’t enough to live on. I remember a big goal at the time was like, man, if we could just get that to 10,000 in sales, that would really open things up for us. But we just never got there.

Still, Butterglory’s name was sometimes mentioned in the same breath in the mid-nineties as Pavement, or Archers of Loaf, and they attracted major-label interest.

Mac’s setlist from a 1993 Butterglory show at Margaret’s Rock’n’Roll Cantina in Chapel Hill; Mac sat in with Butterglory (who were listed as “Butlerglory” on the sign outside the club) on guitar.

Matt Suggs I got talked to by a lot of completely cheesy-ass industry people, which always freaked me out. I wanted to say, “Have you listened to the record? This is not going to get played on the radio.”

In 1996, Butterglory was offered a $50,000 publishing-contract advance – wherein a publishing company buys a songwriter’s catalog copyrights, in hopes that the songs blow up one day.

Matt Suggs They were offering a ridiculous amount of money. It started out at 30 grand, and then it was 40 grand. And we kept saying no. It was ridiculous, because I’m like a twenty-three-year-old working a deep-fryer, making $6 an hour, and I’m saying, “No, thirty grand is too low.” So when it got to $50,000, I said to Debby, “Look man, we should take this fucking money, because there’s no way we’re ever going to sell enough records for them to recoup even half that. So let’s just take their fucking money.”

The publishing company sent a $10,000 check as first payment, and Debby and Matt went to Santa Monica to sign the papers.

Matt Suggs We’re in the office with the big cheese. He comes in with a fucking camera and starts taking pictures of us. I felt like we were the band on Beverly Hills 90210 or something. He said, “Buddy, let me see you smile,” and we had to pretend like we were signing something for the camera. So this guy could sort of sense from me that I felt wrong. I wasn’t very animated. And he starts grilling me. He asks, “How bad do you want it? From a scale of one to ten, where are you?” He’s kind of needling me. And I said, “Man, it depends on what you mean by it. We have a different idea of what it is.” And he says, “Well, you don’t want it bad enough.” That’s how these people operate. So we basically sent the check back and said, “Fuck it.” I had a friend who was a lawyer helping us. He called the company and said, “So how do we do this?” They said this had never happened in the history of the company, where a band sent back the money.

In fall of 1996, Butterglory toured Europe with Guv’ner and Cat Power, headlining shows in Holland and Belgium. Jim Romeo, who worked for Bob Lawton, tagged along as a working vacation.

Jim Romeo (Ground Control Touring) That was kind of an odd tour, because I think that was the Butterglory-breaking-up tour. I could tell that something was going on.

Laura Superchunk toured with Butterglory a lot, and we spent a lot of time together. And it was really fun and great. Until it got to that point where it was clear that Matt and Debby were having problems. I remember we were on tour once with the Wedding Present and Butterglory, and Debby was hanging out with one of the Wedding Present guys too much.

Matt Suggs We had recorded our next record, Rat Tat Tat, in 1997. It was coming out in the fall of 1997, and we had a tour planned. And things between me and Debby just weren’t working out. At the time I never really thought about being in a band and being on tour with a girlfriend. But I think now it would be extremely difficult to do something like that. It was just strange. We weren’t very affectionate towards each other on tour. We pretty much broke up, and I found it hard to continue with Butterglory. Mac and Laura said, “Okay, I understand. But let’s not tell anyone.” Because they were worried about sales – that some distributors might not pick up Rat Tat Tat if they knew we weren’t touring. So I would do interviews where people would ask about the future, and I’d say, “Oh, yeah, we’re going to do this and that.” When I knew the whole time that the band was breaking up. We were scheduled to play a Merge showcase at CMJ that year, which we cancelled. And Stephin Merritt said from the stage that Butterglory had broken up. And it was kind of just done.

Suggs left Lawrence and moved back to Visalia, taking a job in the kitchen of a local restaurant. It was two years before he decided to make a solo record.

Matt Suggs In my relationship with Mac and Laura, I never assumed anything. So I went to them and said, “Look – it’s not Butterglory, so I can’t say if you guys will want to put it out.”

Suggs recorded Golden Days Before They End – the name comes from Roy Orbison’s “It’s Over” – in Lawrence in 1999, with Naron playing bass and Ranjit Arab, who had toured with Butterglory and played on Rat Tat Tat, on guitar. In other words, it was Butterglory with a different drummer. But it sounded nothing like Butterglory. Golden Days is epic; The New York Observer described it as “visceral music that incorporates honky-tonk piano with elements of spaghetti-Western scores: taut, twangy electric guitars, mandolins, snare drums, castanets and the mournful howl of Mr. Suggs’ lap steel guitar.” The four-on-the-floor propulsion of Butterglory was replaced by shuffles and waltzes; the Velvet Underground debt had been repaid, and new accounts opened with the Kinks and Neil Young. Populated by circus performers, skeletons, vultures, palm readers, and ghosts, Golden Days is as visceral and punishing a document of a failed relationship as Blood on the Tracks.

Matt Suggs It was a real cathartic time for me making that record. Part of me wanted to prove to myself that I could still do it. So I gave the tape to Mac and Laura at a Superchunk show in L.A., and they called and said, “We love it.”

Merge released Golden Days in June 2000. Suggs only did one brief tour, out to New York to play Merge’s 2000 CMJ showcase. At the CMJ show, Suggs shed the shoe-gazing indie-rock pose that he had struck with Butterglory, stalking the stage in leaps and bounds like he was playing a monster in a children’s play and conducting the band like a maestro. But not many people got to see Suggs on stage that year.

Matt Suggs The economics of touring got tough, because we were all spread out. Ever since I went solo, tours were pretty much a money drain. Guarantees for shows weren’t the best. And touring can start to get old. Especially if you’re sleeping on the boards. I didn’t really care about it in my twenties. But you get into your thirties, and I’d rather just be at home watching some bullshit on TV.

Golden Days sold 1,500 copies, far less than the Butterglory records. A follow-up, Amigo Row, recorded with Lawrence’s Thee Higher Burning Fire, expanded in several directions from the territory staked out with Golden Days. Suggs wrote the songs on piano, which he had recently learned to play. They flirted with seventies rock and piano balladry, and sixties soul, all while keeping one foot in the Western milieu of Red-Headed Stranger. It didn’t sell any better than Golden Days.

Matt Suggs Every time I finish a project post-Butterglory, I’ve always thought that might be it for me. Golden Days pretty much bombed, and Amigo Row didn’t do any better. A lot of people were surprised that it didn’t do better. But that’s almost been the story of my life with this shit. “Oh, I would have thought that record would have done better.” What can you do? It sold 1,500 copies. I never got into this for the fame and fortune, but sometimes the frustration of never really achieving any kind of success does wear on me. Like, if no one’s listening, maybe I should do my own thing and not worry about putting it out.

Laura I know he wants more to come out of

– or I feel like he wants more to come out of

– putting out a record than it just selling a few copies. And he so deserves it.

After touring for Amigo Row, Suggs returned to Visalia and stopped playing – but not writing songs – for two years before his friends in Thee Higher Burning Fire and Robbie Pope, the former bass player for the Get Up Kids, coaxed him into forming a new band and moving back to Lawrence.

White Whale was a different animal entirely, so to speak, than anything Suggs had done before. It was a collaborative effort, with all five members pushing and pulling the songs, which Suggs wrote with keyboard player and guitarist Dustin Kinsey, into more explosive and strange directions. The band’s only record, WWI, released by Merge in 2006, is a sprawling, circuitous progrock concept album worthy of David Bowie, with driving anthems devolving into overprocessed diversions of burbling electronic keys, guitar feedback, and treated vocals. Lyrically, WWI hews to a nautical theme – the spooky Western plains imagery of Suggs’s solo records had given way to admirals, yeomen, fetching damsels, and talk of going down with the ship.

Most dramatic, however, was Suggs’s transformation from self-effacing singer-songwriter to enthusiastic frontman. WWI features, for the first time, Suggs delivering his songs with full-throated bellows and urgent couplets. “As capably as the band… rocks,” Pitchfork wrote, “it’s Suggs’ theatrical charisma that steals the show.”

Matt Suggs The guys kind of pushed me in that area. And I went with it. It was kind of fun to try something new.

WWI received more and better press than either of Suggs’s solo records and, owing to the enterprising lobbying of Merge publicist Christina Rentz, the record’s release was accompanied by a proclamation from the Kansas state legislature that July 25, 2006, was “White Whale Day” throughout the state. It sold 4,200 – better than Golden Days and Amigo Row, but not as much as Suggs had hoped. The band tried to persuade Mac and Laura to put more money behind the record, but Merge wouldn’t budge from its frugal philosophy – Suggs’s previous sales just didn’t justify an outsized investment.

Robbie Pope Merge did really good with the record. But there was a while where I was on the phone arguing with Laura over money every day. Which sucked, because I love Laura. I think Merge had higher expectations, and was expecting us to tour more. But I wouldn’t rather have had it come out on any other label, that’s for sure.

Matt Suggs My favorite part of my relationship with Merge is that I feel like we’re a part of a community. Which makes it awkward sometimes to deal with the business part of it. A lot of times, doing business, you have to kind of be a jerk. It’s easier to be businesslike with people you don’t care about.

White Whale toured in the fall of 2006.

Matt Suggs It was okay. Some shows were better than others.

Robbie Pope I was going from playing to over a thousand people a night with the Get Up Kids to playing in front of fifteen drunk people in Louisville. But when we got back, we had actually made money. I was shocked. We were a brand-new band, and we went on tour for the first time, and we all came home with money. But those guys had higher expectations, and they were just kind of ready to not do that again for a while. I don’t blame Matt for not wanting to do it full-force. He’s done it in the past, and it hasn’t really paid off for him. He has written these amazing songs, and it just doesn’t seem like he ever caught a break.

Not long after WWI came out, fellow Merge artists Spoon asked Pope to come aboard as bass player. He accepted, and White Whale went on a hiatus. Suggs is working at a record store in Lawrence, and going to school. He hasn’t performed or written songs since White Whale stopped playing.

Matt Suggs I’m just kind of taking a break. Part of me still wants to write, and create. But so much of it isn’t about that. It’s like touring, and talking to people. It’s not just about writing and creating. The thing about me is I feel like I’m always starting over.