1991 to 1993

Matador released No Pocky For Kitty in October 1991, one month after David Geffen’s DGC had released Nevermind by Nirvana. In November, Rockpool featured both bands on the cover, giving Superchunk almost as prominent billing as Nirvana. Within three months, Nevermind had replaced Michael Jackson’s Dangerous as Billboard’s top-selling album; Geffen was moving 300,000 copies of the record each week. By May, it had sold 4 million. The newly discovered affinity on the part of a generation of fourteen-year-old suburban kids for loud, overdriven guitars and earnest melodies played (mostly) by young men wearing thrift-store clothes and T-shirts bearing the names of obscure bands was an epochal shift in the music business.

The Seattle scene that Mac and Laura had toured through in the summer of 1989 had gone from a cool and inspirational DIY uprising to a potential goldmine. Aaron Stauffer was working in the mail-order room of Sub Pop when Nevermind came out – when Seaweed signed to the label, he had negotiated a job for himself – and remembers the day it hit number one. “Bruce came in with a copy of Billboard, and he started punching the air and going, ‘Yes!’ Then he got down on the ground and did some crazy Elvis pose. It was the moment.” Sub Pop, which had been on the verge of bankruptcy, had sold Nirvana’s contract to Geffen, and was earning three percentage points of Nevermind’s sales.

Nirvana’s success sent well-heeled A&R reps from New York and L.A. scrambling to excavate, catalog, and monetize every mane of hair and distortion pedal extant in the Emerald City. In a matter of months, Seattle had been conquered, and previously unknown bands such as Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, and Soundgarden were suddenly bringing in enormous amounts of money for major labels. Even Mudhoney signed to Reprise. Sub Pop and Matador – the latter of which at the time had released just ten full-length records, two by Superchunk – were suddenly seen as gateways to a fortune in previously unexplored musical territory. Pavitt & Poneman and Cosloy & Lombardi were ornery, visionary prospectors who had left the suits behind, lit out for the territories, and hit pay dirt. And now the suits were catching up to them, checkbooks in hand. If there was no one clamoring to put out Superchunk records in 1989, there was now.

May 1992 cover of Alternative Press.

The same month that Nirvana hit the top of the charts, Danny Goldberg was named a senior vice president at Atlantic Records. Goldberg, a former music journalist and executive for Led Zeppelin’s Swan Song label, was at the time Nirvana’s manager, not to mention Hole’s and Sonic Youth’s. In other words, he was plugged into the underground that was going to make everybody rich.

Danny Goldberg I don’t think people were so silly as to think there was going to be another Nirvana. But there was an awareness that there was an audience that Nirvana had, that there was kind of a new constellation. There’s no question that there was a shift in the taste of a mass audience that was dramatic, and it was dramatized by the success of Nevermind.

Jon Wurster We played in Bloomington, Ind., on my first tour with the band, in 1991. And we get there to load in, and there’s these frat guys playing “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” On the floor, not even on the stage. Like that’s where they rehearsed. They were wearing flip-flops, back-hatting. I thought, “Wow. It’s happening, man.”

Glenn Boothe When I started at major labels in 1990, the watchword was always “artist development.” During the eighties, bands like the Cure, and R.E.M., and U2 started slow, but by ten years later, they’re the biggest acts on the label. So the emphasis at the time was, we need to get in with these bands early. But all that really changed with Nirvana. All of a sudden, these bands who could have been the future R.E.M.’s and U2’s and Cure’s were expected to do it in two years, not ten years. Because the labels saw that money could be made.

Aaron Stauffer Everybody was trying to sign everybody. I think the line from Danny Goldberg was, “Sign anything that moves.” That was the party line. And that’s how they put out a Surgery album.

Ian MacKaye Nirvana was a band that would have opened for us. When they signed, Nirvana was selling 40,000 records. Fugazi was selling 200,000 records on Dischord. Keep in mind that the general rule of thumb in the early nineties was that anything you could sell on an independent, the major would be able to sell double right out of the box. So suddenly they’re like, Hello? We want you! Once Nirvana hit, the labels were like, “Oh my god, this is such fertile soil, let’s go and grab some more farms.”

Peter Margasak I thought, “Oh, well, Super-chunk will probably be on a major label within six months.”

In April 1992, Superchunk toured Europe, opening for Mudhoney in Holland, Italy, and Germany. They played a few headlining shows in England, where the response was overwhelming. The British music press fawned. New Musical Express and Melody Maker, England’s most influential music magazines, sought out the band for interviews. NME devoted its cover to Superchunk, photographed through a shredded American flag, with the tagline, “The Yanks Are Coming! Superchunk Lead the American Invasion.” By the time the band returned to the states, they were selling out the Knitting Factory in New York.

May 1992 cover of New Musical Express.

Jon Wurster We played at the Underworld, in London. Which is kind of like the showcase place for a lot of new bands who are just coming out. We start playing the first song, and it was almost like being at the Oscars. A wall of flashbulbs. It was professional photographers who had just been assigned this show, because we were part of this new thing that’s coming over. It was my first time overseas. I remember playing in the Netherlands on that tour, and going in to the van after soundcheck, and just crying. I don’t know why. It was all too much.

Despite the newfound popularity, there was little debauchery on the road with Superchunk.

Jon Wurster I wasn’t sure what it was going to be like on my first tour, so I brought a box of twelve condoms along. Having no idea what was going to happen. But I might want to have twelve of them, you know? I didn’t use any of them. Never opened it. Still have them.

DeWitt Burton (Superchunk roadie; equipment manager for R.E.M.) Maybe somebody might have too much to drink one night and have a bad stomachache the next day, but that’s the extent of the excess on a Superchunk tour.

Jason Ward (Superchunk sound engineer) They definitely came down on the nerdier side. Like, “We’re real tired, where can we go be quiet and go to bed?” The usual thing would be to get back to the hotel and just go to someone’s room and drink about a six-pack and watch some TV. Hang out by the pool and talk or whatever. That was about it really.

Laura Cantrell You’d try to always hang out with them after shows. I was starting to get a little annoyed by the hanger-on factor. Superchunk was enjoying some attention. And for some of their older friends, it was, you know, it could be a little awkward to like watch your friends kind of go off with their new friends. They used to play this goofy game called Celebrity, which is like a version of charades only you put a bunch of celebrities’ names onto slips of paper in a pile.

Laura They would be playing Celebrity. Not me. I would be like, “Shut up! I’m going to sleep.” I can’t play Celebrity, because I don’t retain celebrity information.

Laura Cantrell Watching Laura in those settings, she would always be counting the money. You could see that it was like, “Okay guys. You’re all drinking beer and having fun, but I’m actually finishing the work of the night. You know, we’re not done yet.”

Laura In addition to doing all the accounting for Merge, I did all the business stuff for Superchunk. I did the taxes. I advanced the shows. I booked the hotels. I ordered the T-shirts and CDs to sell on tour. I got paid at the end of the night. I was a den mother deluxe. I put myself in that situation to keep myself sane, and I also didn’t really see anybody else doing it.

Mac We didn’t have a manager or anything. Which meant that there was no one for labels who wanted to talk to us to channel all the stuff through. Labels are obviously more comfortable dealing with managers because they’re like, “Oh, you’re a business guy, you understand.” I think that we kind of warded off a large group of people just from the start because there was no one for them to call except for us. We exuded a sense that we weren’t that interested in whatever you’re selling, but we’re happy to talk to you. You’re nice people, but we’re not that interested in the company you work for.

Laura It was just noise. I had grown up with that whole concept of, “Dude, so and so sold out! That’s not cool!” And the fact that Nirvana had done it didn’t make me want to do it. When the industry folks would come around, I would leave the room.

Not every Superchunk show, of course, was beset by industry types.

Mac We made an effort to branch out into areas, like the South, not known for supporting indie rock. We played a show once in Virginia Beach with Erectus Monotone in the early nineties at the Peppermint Beach Club. We knew Virginia Beach was a total redneck town, but we figured it’s a trip to the beach – how bad could it be? We showed up and the sign literally said ALL YOU CAN EAT SEAFOOD BUFFET SUPERCHUNK. After Erectus played, all of a sudden there were these bleached-blonde girls on stage wearing half-shirts that say ‘Kool’ on them, and they’re throwing out tube socks with the Kool cigarettes logo on them. Then they announced a contest where the girl who can take off her bra under her shirt the fastest gets a free carton of cigarettes! To top it all off, Jim ate sand trying to body surf and skinned the side of his face. You can see the scab in our promotional photos from that time. When it was time to get paid, I went into the office, and the club owner took his gun out and put it on the desk before telling me how little they made that night. He then gave me the reason for why the show went so poorly: It’s “the niggers” who came into town on weekend nights. Holy shit what world am I living in? So that’s Virginia Beach for you.

In early 1992, Superchunk opened for Hole at the Whisky a Go Go in Los Angeles.

Jon Wurster Courtney Love was nuts. Hole only played for a little while and then just stopped. Backstage, she went up to Laura and said, “I hear you’re the hot new rock chick” or something.

Laura I just ran away and went to the merch table. “I’m not going back there anymore! It’s scary!” And Perry Farrell was backstage hanging out with Courtney. Yeah, that was a scene.

Mac While we were in L.A., Danny Goldberg called us and asked for a meeting.

Andrew Webster was traveling with Superchunk as a roadie at the time.

Andrew Webster It was impressive. It was everything you thought a record label was going to be. It was shiny, in a big building with a nice view over L.A. It was a very cultured environment. You felt like you were at a five-star Hilton somewhere.

Peppermint Beach Club, Virginia Beach, Va., 1992.

Mac At one point, the secretary buzzed in and goes, “Danny, Bonnie Raitt is on the phone.” And Danny says, “Tell her I’m in a meeting with Superchunk.” I was like, really? She really called? It would be normal if she called, I guess. But did the secretary really tell her he was in a meeting with Superchunk? Would Bonnie Raitt have any idea who Superchunk was?

Jim Wilbur It was comical. He said, “I’m gonna make you the center of my world! We don’t even have to put the Atlantic logo on the records! I want to use you to look cool. All I want is to be associated with you, and not be a dick.” He actually said that.

Jon Wurster At one point, Mac had to go to the bathroom or something, and Danny left the room, too. Like, I’m not going to talk to you. It was kind of insulting.

Mac No money was ever even mentioned. It was just implied that there was a lot of it. Part of the thing that people would always offer was, you can still have all that stuff on your own label too. Or maybe we could buy your label. Like it wasn’t just the band that’s interesting, but the label also. But none of these things ever got to the point of a deal memo even. It was more like, “Hey, anything’s possible.”

Andrew Webster That same day, we also met with Danny’s wife, Rosemary Carroll, who was a lawyer for a lot of bands. Which was funny, because her take on the whole industry play was totally different from his. Danny was quite anxious to get them all signed and tucked away. She was a little bit more reticent and a little more encouraging to forget about the money, because the money would go away.

Mac The old Good Cop Bad Cop routine!

Jim Wilbur She said, “You know, I love my husband. But I don’t necessarily think that you should sign with him.”

Andrew Webster She told a story about fIREHOSE. They knew that Sony was trying to get rid of cassettes, and so they wrote into their contract specifically that Sony had to produce cassettes of their albums. None of this all-CD bullshit. And when the album came out, Sony pressed however many cassettes they needed to fulfill that contractual obligation. But they neglected to press vinyl, which no one thought would go the way of the dodo. It was sort of an object lesson – you can’t control this process as much as you think you can. You can’t outguess these jokers. You do the best you can, and take the things you can get. But don’t expect you’re going to outwit an industry designed to get their own best out of this.

Jim Wilbur We left the meeting with Danny, and went and sat in the van. There was horrible flooding in California at the time, and there was this deluge of rain pouring down on us. And Mac said, “Well, there’s pros and cons to be considered here.”

Mac Those guys are all real good talkers, so sometimes you start thinking, “Oh, maybe he’s right. It could be really cool.” We listened to what he was saying. We didn’t just say, “Fuck you!” But if you think about it long enough, where are the examples of a band like us being happy, or successful, on a major label? Hüsker Dü signed to Warner Bros., and I thought the records got worse. And then they broke up. Maybe they would have made the same records on SST, but it’s easy to look at it and say, That’s what happens when you work with a major label. Same with the Replacements. I like Tim, but those Sire records got progressively worse. Is that because they were on a major label? I don’t know. You can never really pin it on something, but it always seems to happen. If our records are going to sell less and less, I’d rather have them sell less and less in a creative situation – a cool situation – than a depressing one where it’s just a job to do. There’s all this money, but that’s only appealing to people who don’t know how it works.

Laura Or for people who don’t see a future.

Jon Wurster I think it was obvious we weren’t going to. I’m the only person in the band who’s ever been on a major label. And I know how awful it can be. It can be really good if the stars are in your favor and everything kind of falls into place, and somehow you connect with one song that everyone else connects with. But that’s two percent of the people who sign to major labels. I had already experienced the worst of it, and I didn’t really want to do that again.

Jim Wilbur We talked about it for twenty minutes, and said, “You know, I don’t think it’s worth it.” And the meeting was done. It was like, Okay we’re not signing to a major.

Danny Goldberg You don’t win them all. They just were interested in doing their own thing. And now that they’ve built this spectacular record company, so obviously it was the right thing for them to do.

Phil Morrison (Director, Junebug, Upright Citizens Brigade, and countless music videos) The real reason Superchunk never signed is that they knew that labels were mistaken to want to sign them. And why should Superchunk participate in that mistake, just because there might be something glamorous or exciting about it? It shouldn’t be surprising that a really excited music fan who’s an A&R person at a big label would want to sign them. There were really enthusiastic music fans who then got these jobs, and so of course they wanted to sign these bands that they loved. It was a faulty system.

Jonathan Marx (Lambchop) They weren’t desperate for cash; they weren’t desperate for fame. The only thing they were desperate for was the thing that they were doing.

Tom Scharpling That thing was over before it was started, that whole revolution. You see guys like Tad signed to major labels. Guys who had no place on a major label. Surgery, all these bands getting signed and it’s like it was a morbid correction in a way. Like the stock market will take a hit and occasionally correct itself, and all of a sudden the floor will fall out and everything recalibrates. That’s all that was. That was not meant to happen.

Aaron Stauffer So Superchunk was totally against it. And we were initially against it, and then once ‘93 rolled around, and we’d done this big long tour on an indie record, and we were on MTV pretty regularly and yet we weren’t selling – we were bottoming out at 20,000. And we were fucking poor, and we were like, “Let’s just sign. Fuck it. We can’t stand each other, and we need hotel rooms.”

Phil Morrison Seaweed had come through Chapel Hill, and we were all at this diner called Breadmen’s the next morning, after a show at the Cradle, having breakfast. And Aaron says, “Dude, we’re signing to a label. Guess who we’re going to sign with?” And Mac says, “Geffen?” “Worse.” “Um, A&M?” “Worse.” And Mac named every label, and every time he said something, Aaron said, “Worse.”

In 1995, Seaweed signed with Disney’s Hollywood Records.

Aaron Stauffer Mac and Laura said, “You should just put your album out with us.” Mac was definitely like, “It’s a bad idea. Don’t sign.” He was right. But we decided to go for the money.

In 1993, Steve Albini wrote an article for Chicago journal The Baffler called “The Problem With Music.” It was an astringent and clear-eyed case study of the process by which a band is signed to a major, beginning with the seemingly hip A&R rep who first makes contact: “After meeting ‘their’ A&R guy, the band will say to themselves and everyone else, ‘He’s not like a record company guy at all! He’s like one of us.’ And they will be right. That’s one of the reasons he was hired.” It ends with a detailed accounting of how, after lawyers, managers, producers, promotional budgets, and all the other fees necessitated by the major-label system are taken into account, a band can sign a $1-million contract, sell 250,000 copies of their first record, and end up $14,000 in debt to the record company. Its final line is, “Some of your friends are probably already this fucked.”

Brian McPherson They were traditional record deals. They were worldwide, up to seven records. Usually the seven records were all at the label’s option, with perpetual copyright ownership vested in the label. And everything was recoupable. So they’ll give you anywhere from $150,000 to $500,000 per record. You’d pay for the recording out of that fund. And they’d own it and you’d have to pay all that back even though they own the master.

Danny Goldberg People like Steve Albini have always said the majors are evil and you’re going to compromise by being there. I think some artists were better off with majors, and some were better off with indies. I think it was good for Nirvana. Nirvana had a lot of problems, but they didn’t derive from their record company. I think it was fine for Pearl Jam, I think it was fine for Rage Against the Machine. I think it was fine for Sonic Youth, who continued to spend another fifteen years in the major system doing great work. There were acts that may have done it for the wrong reasons, or have been lied to. But there are people on indie labels that have bad experiences, too. Not every indie label is like Merge. There are indie labels that stole from people. These generalities are good if you want to get quoted and act like some self-righteous person. I have a lot of respect for Steve Albini, but my experience with him when he produced Nirvana was that he got $100,000 for a few weeks’ work. That seemed to be good pay from a corporate company. And he earned it. As far as I know he kept the money. I thought In Utero sounded kind of like the other Nirvana record.

Lou Barlow (Sebadoh, Folk Implosion) I had this radio hit with the Folk Implosion called “Natural One,” and we signed to Interscope. The Interscope thing was just so bizarre. We’d go to meet the head of the label. And he’s sitting in his office with the Mellotron that John Lennon used on “Strawberry Fields.” And you’re wondering, what the hell is it doing in his office! Why isn’t it in a studio?

Danny Goldberg It depends on the kind of music that they wanted to make, and it depends on what their ambitions were. Not every artist was happy selling 50,000 records, which in the nineties was what you often would get at indie labels.

Lou Barlow When we were meeting with labels before we signed, we met with Sylvia Rhone, who ran Elektra Records. And she was just totally full of shit. She was this older woman, with her hair pulled back and this little designer sweatsuit on. We had this totally bizarre conversation about music. And I left the room, and immediately she tells the person who accompanied us in there, “He doesn’t have what it takes.” And I kind of got mad about that when I heard about it. But you know what? She’s right. I don’t have what it takes. At all. I’m not even going to argue that point. It’s just a bummer. Dealing with the amounts of money that those people deal with – it’s just a bummer.

Aaron Stauffer We fucking met with the head of Disney. That’s how we ended up signing to Hollywood Records. Michael Eisner came and had a meeting with us for a half an hour. If we got Eisner in the room for a half an hour, that’s kind of big, right? It meant they were serious. They wouldn’t have had him in there, you know? But it was awful. The whole thing was awful from the moment that we signed the contract. We got to spend an ungodly amount of money and make the rock record that we’d always dreamed of. That was great. And being on a bus, and that kind of shit. But the price to pay was that we basically fucked ourselves.

Ian MacKaye The truth is that if Fugazi had signed to a major label, the pressure of the label, the structures of the label, the kinds of compromise that would have been necessary to engage in that machinery – I think that would have broken us up.

Aaron Stauffer They were like, “I don’t hear the hit.” Which pisses you off. So you go back and write the hit. But it was annoying. I just remember one of the A&R guys playing us the Alanis Morrisette album, in his car. And saying, “This is going to be the next big thing.” And we were like, “This guy is on crack. This is fucking awful.” And he’s in this purple suit and what the fuck? Why do we even have to listen to this Canadian shit? And lo and behold, he was right. But who would have fucking thought?

Ian MacKaye I’ve heard early demos of the songs that I think are just insanely great, and so beautiful. And then by the time they come out on a major label, they’re packaged in a way, and they’ve been treated in a way, that has just made them – there’s just nothing there. There’s no substance anymore. I’m in a band called the Evens with my partner Amy Farina, and we have a song with a little melodic hook on it that happens once in the song. And this friend of mine who’s in an extremely popular band listened to the record. And he said, “I can’t believe you just did that hook one time. We would have to do it like twelve times.” Because there would be a producer going, “That’s it, that’s the hook!” I said, “But it sounds so right just once.” He goes, “It is right. But we would have done it twelve times.”

Danny Goldberg I never was involved in creative problems like that. There have been people in major labels who’ve tried to interfere with artists, and intimidate them into doing things that they didn’t want to do. After the nineties, most artists that had decent lawyers or managers were able to negotiate legal creative control. Then it was just a question of, psychologically, if they get intimidated when somebody says, “We want you to change this.” But in those situations, artists had the right to say no.

Ian MacKaye You have full creative artistic control. Sure you do. There’s no doubt about it. That’s what the language says. But if the label says, “You know, we’d be a lot more excited by this if you’d just do this” – you’re essentially the object of a huge investment. And you want to please the investor. And I just can’t help but think that – though you have full artistic control – those decisions are going to be heavily influenced by wanting to please those people who have given you this opportunity. And also, you want to sell a lot of records. That’s why you get into that world.

The next Seattle? For months, music fans and record-company execs have been searching for another town to crown as the alternative-rock capital of the U.S., now that so many feel the Puget Sound city has grown passé. Plenty of places… have been very eager to oblige, but it’s the sleepy college burg of Chapel Hill, N.C., that has caught the fancy of the music world, including rockers themselves… . Superchunk is a noisy band that plays superpower-pop by blowing melodies out of the water into a stinging spray. When it toured England last spring, Superchunk gained added cachet by being featured on the cover of the British weekly New Musical Express, but the group and its lead singer, Mac McCaughan, seem genuinely indifferent to mainstream success, despite interest from major labels.

—Peter Kobel, “Rock This Town,” Entertainment Weekly, January 8, 1993.

Throw me a cord and plug it in / Get the Cradle rockin’… / Too bad the scene is dead.

—“Chapel Hill,” Sonic Youth, Dirty, 1992.

Glenn Boothe People were noticing North Carolina. And people at the labels I worked for knew that I was from North Carolina, and they would ask me, “Can you introduce me to Superchunk?” Basically it was kind of this feeding frenzy, and that led to the whole “next Seattle” thing. Which was funny because we never had the Pearl Jam, or the Nirvana. But for some reason everyone thought this area was going to have that. All these bands got signed based on speculation.

Jeb Bishop It had a flavor-of-the-month vibe about it. People were bemused that this was happening, but also trying to keep some kind of perspective on it, and realize that this didn’t mean we were all going to get rich overnight or anything. It just meant that somebody was trying to make a buck.

Ron Liberti The people that were down scouting the bands, I think that they were looking for the Chapel Hill sound. And there wasn’t a Chapel Hill sound. So it was tough for them to scoop us up as easily as they did in Seattle. And we were going to do it whether they helped us or not. We were already doing it. We didn’t need them. We had Merge.

Jack McCook I thought it was absurd. That’s when there was an influx of shitheads coming to this cool little town. Every band was “great” for a while. And everyone had a band. Yeah, that was a nightmare. I couldn’t stand it. Everyone had a label. That’s when I moved to New York. It’s much more interesting up there than some guy from Kernersville, N.C., trying to be a music mogul. Or living the rock’n’roll life. When I lived in New York, these fuckers were calling me from Chapel Hill, people I hardly knew, to ask me if I knew any managers. I guess they thought I’d moved up there and jumped into the music industry.

The early nineties indie boom didn’t just take in bands. Hundreds of labels popped up, hoping to find a diamond in the rough and ride them to glory and riches. Or at least to a sustainable business model. Moist/Baited Breath, a Chapel Hill label, found early success with Beyond the Java Sea, by a short-lived band called Metal Flake Mother whose frontman, Jimbo Mathus, went on to found the Squirrel Nut Zippers. They moved into nice offices and cosponsored 1992’s “Big Record Stardom Convention” in Chapel Hill, and promptly went out of business. And the bigger indies had the same stars in their eyes.

Lou Barlow Sub Pop totally, really went for it. They really tried to go whole hog, fucking big time.

Karen Glauber (Editor of HITS, independent radio promoter) They expanded, and they started hiring all these people. They put all their eggs into a Sebadoh record. It wasn’t that successful, to say the least.

Lou Barlow We had started writing all these electric songs, which became the Bubble and Scrape record. And I was kind of looking for a label. So I sent four songs to Mac, and Merge offered to put it out. And I was actually going to do that. But that’s when Sub Pop kind of stepped in and said, “We’ll give you $20,000.” And that was it. There just wasn’t any question at that point. Do we work day jobs? Or do we sign this record contract and get $3,000 apiece to live on for the next three months? It seemed like an astronomical amount of money.

Aaron Stauffer Sub Pop was always spending money. And they were also putting out the illusion that they were spending even more money than they actually did spend. They weren’t ever trying to be a little label. They had these stoner, heroin-addict fucking rockers doing their accounting. It was just unbelievably mismanaged.

Lou Barlow I kind of wish modesty had stepped in at that point, and that we had gone about it a bit slower and not answered record sales by spending tons more money – more money than we had – to sell even more records. They sat down at meetings and said, “One hundred thousand is good. But if we turn this over we could be looking at a million!” That’s how Bruce Pavitt was talking back then.

Steve Albini The sort of opportunist labels, like Sub Pop and Matador – labels that sort of sold off their bands at the first opportunity, those people were looking at it as, not as a cultural enterprise, but as another in a series of business enterprises. They were thinking of it in monetary terms before they were thinking of it in cultural terms.

Laura Cantrell I think Mac and Laura kind of got some schooling in the Matador experience. I’m not saying that it was distasteful to them, but I think they were just, ‘We’re going to North Carolina and doing it our own way.’ I don’t think they were impressed.

Mac Our first statement from Matador was a lesson in record business accounting. We could see that Superchunk had sold some copies and made a bit of money – more than our advance, which was only $2,500. But we had recorded No Pocky, which hadn’t come out yet, so the cost of that recording was cross-collateralized against the earnings from our first album. In other words, we wouldn’t see any of the money our first record earned until we started making money from the second record. It’s totally standard, not something Matador was doing in an underhanded way, but it just made me think, “This isn’t so simple.”

Jon Wurster Honestly, no slag to Matador or anything, but it was sort of hard to find our records in stores sometimes. If you wanted to buy our record, you’d almost have to come to the show and buy it from Mac and Laura.

Mac We were introduced to Corey Rusk and Touch and Go through Albini. Sometime during the process of making No Pocky for Kitty, we were talking about Merge and Steve said, “You should talk to Corey.” All I knew about Touch and Go was that it was a pretty heavy punk-rock aggro label that had put out Steve’s bands – Big Black and Rapeman – and Scratch Acid records.

Touch and Go is a legendary label founded in Michigan in 1979 by Tesco Vee and Dave Stimson, who published a hardcore zine of the same name. Rusk took over managing the label in 1981 and moved it to Chicago, and put out records by the Butthole Surfers and the Jesus Lizard. Rusk did not use contracts, and worked on a fifty-fifty profit-split basis with bands, as opposed to the industry-standard 12 percent royalty paid to bands.

Corey Rusk When I first heard Super-chunk, they instantly became one of my favorite bands, and I couldn’t stop listening to them. Merge had just been putting out 7-inches, and wanted to put out this compilation of Superchunk singles. The proper new Superchunk album had been on Matador, but they wanted to put out this compilation on Merge. And they knew that the demand for it would be quite high, and that they hadn’t really done anything on that scale with their label before.

Mac It’s one thing to get together a few hundred bucks for a 7-inch and fold your own sleeves, but making a bunch of CDs was a bit beyond us. By the time Tossing Seeds came out, we weren’t just talking about a thousand or two – I think we initially made ten thousand copies of that collection. At two bucks per CD, $20,000 wasn’t an amount of money we had lying around to manufacture, much less promote, that record. But we wanted it to be on Merge, and not Matador. We had put most of the singles out on Merge and wanted Merge to benefit from that. Plus, we were already thinking that Merge would be the home of Super-chunk in the future.

John Reis (second from right) getting too much advice from the band during the recording of On the Mouth in Los Angeles, September 1992.

Corey Rusk The typical person who starts an indie label is someone who loves music and really enjoys working with artists and promoting their music. But that same personality type, more often than not, is not that organized, and just can’t wrap their head around all the logistical things that need to be in place for their company to function smoothly on the whole sort of nonmusic side of things. It was a really brutal environment for indie labels to try to exist in back then. Basically, the labels only got paid when the distributors needed something from us. They’d tell you the check was in the mail, and they had not mailed it. How can you run a business when you just couldn’t even predict your cash flow? I recognized that some of my peers just didn’t have their shit together in this sort of backend, just boring stuff – getting the records pressed, taking care of cash-flow management so that you don’t run out of money to press the new records, dealing with distributors, getting paid from distributors, keeping track of all the accounting. Touch and Go was just really good and efficient at that stuff. So I thought, maybe I should offer this as a service to some other labels that I like. And if we formed a small group of labels, we would be more likely to have a new record each month that the distributors would want, so they’d pay us on time.

Steve Albini The people that survived are the people that became competent businessmen sort of by necessity, like Corey Rusk and Ian MacKaye. Corey actually went to a community college and took business classes. This is a guy who hated school with a passion. When he realized that he was going to be handling hundreds of thousands of dollars and, you know, the lives and careers of a bunch of his friends, he decided he had to take it seriously.

Mac So we put out Tossing Seeds on Merge, but with Touch and Go handling the production and distribution – basically, they put up the money to produce all the CDs, dealt with getting all the CDs and artwork printed, sold it to distributors, and took a 30 percent cut. It did really well, and the whole process was exceedingly smooth. We were actually getting paid by Touch and Go. I remember the first check from them blew me away. It was like $18,000 or something, at a time when we’d put out two records on Matador and hadn’t seen a cent yet beyond the small advances.

In the fall of 1993, Superchunk delivered its third record, On the Mouth, fulfilling the band’s deal with Matador. Recorded and mixed over six days – the longest time the band had spent recording to date – at West Beach Studios in Hollywood with Rocket From the Crypt’s John Reis.

Once they got to L.A., recording On the Mouth was a sometimes frustrating experience.

Mac They were having trouble getting a kick drum sound. It was taking a really long time, which meant we had to hang out in the tiny little lounge with the engineer’s vast and “eclectic” porn collection, which we really did not want to be watching.

Laura I wonder who was making those guys watch the porn collection? Those damn tapes must have been putting themselves in. Recording studios are so sophisticated.

Mac At some point the engineer, Donnell Cameron, suggested that we just throw a fat-sounding kick-drum sample on there that would be triggered by Jon’s kick.

Jon Wurster That was like spitting on the Bible. The band whose sample we were talking about using was a hardcore band called Jughead’s Revenge. And I remember Mac saying plain as day: “I am not going to have a sample from a band called Jughead’s Revenge on my record.”

Mac Just someone please capture how it sounds in the room! Did Fleetwood Mac need a sampled kick when they recorded at West Beach?

Three years into the Nineties and nostalgia for the Eighties has already begun. Bands like Seaweed, Rocket From the Crypt and Drive Like Jehu are bringing back the DIY attitude and heartland punk-rock sound of Hüsker Dü and the early Replacements, recalling a time when SST was the cool indie label and corporate America had never heard of Sub Pop. Superchunk, the unofficial flagship group of this quasi movement, has been predictably labeled the next Nirvana – and not entirely without reason. Both bands share a penchant for hummable melodies mixed with blaring guitars, unintelligible lyrics, good drumming and a wariness of major-label sellout. On the Mouth, Superchunk’s first offering since grunge took over the charts and fashion magazines, is no Nevermind, though, and doesn’t try to be. Instead, the album refines and tightens the sound Superchunk established on its previous releases long before anyone considered punk rock commercially viable.

—Rolling Stone, review of On the Mouth, April 15, 1993.

Tom Scharpling I liked the first album a lot. I liked No Pocky a lot. But On The Mouth – that’s an album with a capital A.

In January 1993, the month before On the Mouth came out, Atlantic announced that it had purchased 49 percent of Matador. By that point, Superchunk had already decided to put out its future releases on Merge, with the help of Touch and Go.

Danny Goldberg I was close friends with Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore and Sonic Youth. They said to me that Matador was a very special place and the people that ran it had exquisite taste and credibility. So Atlantic bought half of Matador. The two most interesting bands that Matador had at that time were Pavement and Superchunk. The only act that didn’t stay with Matador was Superchunk. Pavement did, Liz Phair did, Yo La Tengo did. And none of them had long-term contracts so any of them could have left. But you’re not going to get everything you want, and there are artists that just wanted to stay in the indie world.

Brian McPherson These guys in the suits, they look down and say, “Oh let’s buy these little things.” Which is why Merge has always been so unique, because it’s never sold out. Even Gerard and Chris, you know, have sold Matador several times. And done really well.

Artwork from On the Mouth cover

Mac Matador was the far “cooler” place to be. They had Pavement and Teenage Fanclub, working with Chris and Gerard was great, plus walking into their office in the Cable Building on Broadway just felt cool to us kids from North Carolina. But for Merge, Touch and Go seemed a lot easier to understand, and a lot more profitable to boot. Corey knew we had another record we owed Matador, and he said, “Why don’t you see if Gerard would be interested in having Matador put the next record through Touch and Go, like Merge did with Tossing Seeds?” I called Gerard. I remember standing in Laura’s kitchen on the phone with him. He just kind of laughed and said, “I don’t think we’re interested.” And why would he be? Matador was a real label, and I was basically saying, “Do you guys need a little help from Corey?” So that was probably a little insulting. But what did I know? I guess they did end up getting help from Atlantic, though. After we left, they took out an ad in Spin that joked: “Superchunk Blew Us Off! But we still have suckers like Jon Spencer,” or something like that.

I was maybe twenty-seven years old, living in Seattle. I lived on a street with a liquor store on the corner, and every holiday season there were some reindeer, holly leaves, and whatnot painted on the windows of the place. There were some elves on there, too, and there was a big Santa. Nobody ever seemed to think it was dubious, funny, or sad that the list Santa was reviewing said CIGARETTES, MAGAZINES, BEER, WINE. People just walked in and out, bought their cigarettes, magazines, beer, or wine, and maybe a lottery ticket. Those holiday window decorations went up ambitiously early, around the end of October each year, and they summed up how I saw the world: a place that was equal parts funny, sad, dubious, and seemingly not noted by the people wandering through it.

Further down the hill on Queen Anne Avenue was, and certainly still is, a bar called The Mecca, the kind of dive where big, angry Northwest lugs made for violent and eventually sad and emotional drunks. My friend Dave and I would kill time sitting across the street in front of Uptown Espresso and laughing at the big, violent, and eventually oddly intimate and loving near-fisticuffs that these roughnecks would choreograph on the sidewalk after spilling out of The Mecca. We would sort of give it this play-by-play. “Wallet Chain is pissed off and he’s not gonna take it anymore!” and then within fifteen minutes, “Ah, Wallet Chain is sorry, Car Club Guy. He loves you man. Give him a tough-guy hug like he wants. There you go, yeah, pound each other on the back so everyone knows its not actual love, since you guys are so tough.” We had the sense to keep our comments low, but more than once we were laughing too hard and staring too obviously and one of the knuckle-draggers would cross the street and give charge – like a Bison letting a family sedan in Yellowstone Park know who’s running the show.

One night I got up the courage to go into The Mecca and hit on the waitress – she was tall and pretty and maybe five notches out of my league. I had a crush bigger than the sky on this girl and always saw her around the neighborhood. I sat at a booth and ordered coffee from her. Made her laugh with some riff or joke about the place she was working in, and then asked her what she was doing when she got off from her shift. She said she might be meeting some guy – hinted at a sort-of boyfriend. At any rate, some guy was maybe picking her up at closing time. Most likely one of the ham-fisted cavemen that coated their brains in this smoke hole. So I pulled some huge heart and guts out of nowhere and said that I had some writing to get done, but I’d swing back by around closing time and if the guy didn’t come around I would take her out to a late dinner at this Twenty-four-hour place called Minnie’s. Anyway, she smiled and said that sounded good, the guy never showed, we went to Minnie’s and six months later she’s moving to New York City with me. Where does a twenty-seven-year-old shut-in / wannabe writer get the guts to taunt (from across the street) tattooed bruiser thugs with shaved heads and goatees, then sneak into their dive to steal their waitresses or girlfriends? That’s where this record comes in.

I bought On the Mouth completely by accident, three years after it had come out. Bought it at this little record store by the espresso place. Superchunk wasn’t a band I knew anything about. Merge wasn’t a label I had ever heard of. I wasn’t an alternative-rock snob searching out new releases from hip bands to get into – I was a bartender/dreamer/loser geek with a pocket full of tips taking a chance in a record store; something that more often than not left me feeling just as alone or as uncool as I felt before I walked in. I can’t tell you why I picked this CD up. Once I got it home I listened to it, and then again, then once more, once after that – pretty much constantly. I would honestly be surprised if there were seven days in 1996 that I didn’t play it at least once all the way through. On the Mouth might be the one prefect top-to-bottom American pop punk album. I’m no record producer, but I think I’ve figured out a few things about how they made On the Mouth so perfect. I think their guitar tone in the studio was achieved by patching the first guitar track through a long history of D-minus grades and day jobs that somehow didn’t break your spirit, then it sounds like maybe they did the guitar overdubs a decade later alone in a studio apartment, where self-doubt makes you wonder if you didn’t make a big, big mistake by being such a smart-ass in class way back then. The drum sound, I think, is achieved by recording the drum kit with four separate mics set up in the four separate basements of each best friend you’ve made since the sixth grade. The bass sound is crafted with a more complex recording technique. In order to understand it, you must first sleep alone for at least a few years contemplating how it seems nature has designed the heart to beat strong and steadily in the chest, always a solid low boom with solid meter, no matter how half-hearted or half-assed life might seem when you’re lying there alone staring at the ceiling. And Mac’s vocal, loud and shy at the same time, is something you can’t hear half of the time, yet you somehow understand every word. I’m not sure how the vocal is recorded, but I’m pretty certain it has to do with setting up a mic in a separate room, then asking Mac to recite every string of words that everyone with any heart has ever had floating around jumbled in their head and not even known it. And I think there’s a program you can run the vocal take through that will automatically put it in the tone and manner of every single feeling you’ve had on the tip of your tongue and haven’t been able to articulate since age twenty-one up until the day you play track one of this set of songs. But like I said, I’m no engineer or producer, so don’t quote me on the recording techniques used in making On the Mouth as I could be off base here.

One night in the autumn of 1996 I was bartending at this place where I worked a few nights a week to supplement my eating and writing habits. It was maybe my fourth year bartending, and at this point I was starting to wonder if maybe bartending at this place was all I was ever going to get around to doing with my life. Not that bartending is a bad gig and not that the place was a bad place to spend your nights: a quiet little upscale bistro with five barstools where patrons were keen to buy expensive drinks, keep conversation clever, and tip accordingly. But it was starting to seem like maybe whatever guts I thought I had were gone or temporary and this job was going to be the long haul for me. And if you know anything about bar stories, you know that this is the point that goes, And guess who walks into the bar and orders a drink? That would be Mac from Superchunk. A regular of mine was with him, a guy who did publicity and lined up interviews and things for bands and clubs in town as far as I could figure. Superchunk was playing somewhere that night while I was slinging drinks, and he and Mac stopped in for something before the show. I don’t think I said a word past hello and what can I get for you. I remember overhearing Mac asking the publicist something skeptical like, “Why does some big music magazine want to follow around some loser band from North Carolina for a week?”

I was just some guy who felt like a loser most of the time, too, and I couldn’t believe the guy who was in that band that made that record could feel like a loser as well. How could that be? And that might have been the moment I realized this whole “loser” thing was an odd con job of sorts from the brain. I don’t really know what snapped or changed, but I found my guts again. I quit my job after the holidays and was moving to New York that spring no matter what. Tonight as I type this, the huge guitars are fading out on the last bash and feedback at the end of “Swallow That,” that part of the album where the meter slows and staggers to an end just before “I Guess I Remembered It Wrong” takes a deep breath and kicks in to bring everything full speed again. It’s thirteen years later, and I’m up too late with these songs like I’ve always been. The sky’s already getting a little bit light outside, and in a few hours an October sun will rise and start making downtown New York orange in transition. Then I’ll grab some coffee from the café down the street from my place on Eleventh Street and get back to writing – maybe read this over and make sure I wrote about Mac enough to conceal the crush I had on Laura.

Ron Liberti Matador was king shit back then. I thought, God, Superchunk really does care about this place. And they can do it.

Jon Wurster I don’t even remember there being like a real discussion about it. I’m sure at some point, Mac just said, “You know we’re thinking about putting the next record out on Merge. Is that cool?”

Laura Cantrell I was friendly with They Might Be Giants, who were on Warner Bros. at the time. I was talking about Superchunk with John Flansburgh, and I said, “Oh yeah, they’re not going stay with Matador. They’re going to do their own thing.” He was like shaking his head, like, “They’ll be back. They’ll find out they need the money to do what they want to do. They’ll need to be back on the corporate bandwagon.” I said, “I don’t know.”

Andrew Webster They said, “We’re going to put out records that we like. We’re going to do it in an honest, transparent way.” That’s how you get successful.

Jim Wilbur The whole “indie rock” thing irritated everyone in the band. This isn’t an ideology or a religion. It’s just business. It just makes sense to do it this way. I mean, we’re all highly educated people. And we weren’t trying to be rock stars. We’re trying to make a sustainable way of living. And you know, pay rent.

Mac Touch and Go basically taught us how to be a record label. You can put out 7-inch singles and cassettes and stuff all day, and you’re just kind of paying bands with copies of their single and then it goes out of print. But once we started doing albums, it was real. And we essentially patterned ourselves in almost every way after Touch and Go. We adopted their profit-split deal and just kind of learned everything we could.

Corey Rusk We gave them advice all the time, whether they were asking for it or not. We’d be analyzing every release that went through us on spreadsheets: What are all the costs involved here, and how many do we think we’re going to be able to sell? Are the two wildly out of line? That is where so many indie labels get in trouble. They’re really well-intentioned people, who are so enthusiastic about the music they’re putting out that they just feel sure; their gut instinct says, “Spend this money. It’ll work out, we’re going to sell so many, because this band is so great.” But at the end of the day, that’s the downfall of so many labels, because it’s easy to get carried away beyond the point of reality. I think with a lot of labels that we work with, for better or worse, we’re kind of the voice of reason. Quite often, labels don’t want to hear it. They’re like, “No you don’t understand.” And our job is to try to show them – “Look at this spreadsheet. Even if you sell this many, we’re still in the red. We really have to make some changes to how this is being set up so that it doesn’t work out that way. And you stay in business and we stay in business.” I’m sure I had plenty of those discussions with Mac and Laura along the way.

Mac The Touch and Go folks definitely thought it was kind of novel to be working with a label from a small town in North Carolina. So that became kind of a running joke – “Where do you guys get a fax machine in Mayberry?”

Ed Roche (Label manager, Touch and Go) I was born and raised in Chicago. I had absolutely no idea whatsoever what North Carolina was like. One time when I called down there to talk to Laura, John Williams – Merge’s first employee – gave me her home phone number. I asked, “Are you sure it’s okay that I’m calling her at home?” And he told me, “Yeah, you just have to wait a little while because she’s going to have to climb up the pole to answer the phone.” And I’d seen Green Acres as a kid, and I fully believed him. I did not question that in the slightest.

Laura Touch and Go took 30 percent off the top. And then we were left with the rest, the other 70 percent. To try and compensate for Touch and Go taking 30 percent, we gave the band 70 percent of what Touch and Go gave to us. Leaving Merge with 30 percent of 70 percent. It was the only way we could think of to make it viable for the bands to be on Merge while we had this distribution deal. And it definitely made things hard for Merge. And as time went by and we started to sell more records, it became apparent.

Merge’s early catalog reads like the manifest from an indie-rock ghost ship that haunts the shoals off the Outer Banks. Aside from the Superchunk, Wwax, and Bricks singles, it’s a list of now-defunct – and often then-defunct – bands that once populated the bars of North Carolina. There were the already-gone Angels of Epistemology; Erectus Monotone, a four-piece featuring Subculture’s Kevin Collins that fused eighties dreampop, spastic rhythms, and vestiges of hardcore aggression; Pure, an Asheville, N.C., band, equal parts Joy Division and Dinosaur; Finger, Raleigh’s trash-rock heroes; and Seam, a Chapel Hill band fronted by Bitch Magnet’s Sooyoung Park that Mac briefly played drums for. There were occasional forays out of North Carolina, mostly involving the projects and friends of Pen Rollings, who had been in an influential Richmond band called Honor Role. Rollings’s dark, complicated new band, Breadwinner, was Merge’s tenth release, and Coral, another Richmond band featuring Honor Role’s frontman Bob Schick, was its fourteenth. Many of the early Merge bands were so short-lived that Mac complained of the “Merge curse” in a 1991 newsletter.

Superchunk’s relentless touring also brought folks such as John Reis into the fold, and began to relieve Merge of the burden of being perceived as a regional label. Mac and Laura met Reis on tour in 1992, when Superchunk played with Rocket From the Crypt, which sounded like a Jerry Lee Lewis–Misfits hybrid. In addition to asking him to produce On the Mouth, they put out 7-inches by Rocket and by his other project, Drive Like Jehu (both bands ended up signing to Interscope).

But Merge was still, by and large, the Superchunk label. That changed in July 1992, when, following the success of Tossing Seeds, Mac and Laura released another record through Touch and Go, this time from Polvo, a Chapel Hill four-piece featuring the perverse guitar heroics of Dave Brylawski and Ash Bowie. Polvo was a disheveled and detuned glorious mess that reveled in unusual time signatures, unconventional song structures, and Eastern tonal scales. They were hailed as leaders in the math rock movement, but played with an orchestrated imprecision that implied access to some sort of alien logic system.

Bill Mooney The first time I saw Polvo was at a house party. They were playing in the basement. I was upstairs and it sounded like this kind of a growl in the house.

Mac I was at that same party. They were completely out of tune and completely great.

Cor-Crane Secret came out in July 1992, three months after Tossing Seeds.

Matt Gentling (Archers of Loaf) One of the coolest things I remember was the whole town getting excited when that album came out. We went to a party, and the Polvo record was on, and it was brand new, and everybody just got kind of swept up in it.

The record, a guitar-rock classic, garnered international attention. A Melody Maker critic described Polvo as “the first new American guitar band I’ve heard for months who owe no debt to the fuck-art-let’s-rawk Sub Pop aesthetic” and praised Cor-Crane’s “effortless command of the more vibrant hues of the Nineties guitar spectrum.” Sonic Youth invited the band on tour.

Mac That was a big deal for us. Because it made it clear that Merge was not just about Superchunk and a couple cool 7-inches here and there. It was a full-length record, that we put out, by a really good band in its own right.

Merge newsletter, summer 1991.

Anti-Superchunk flyer from 1991 for Garbageman, led by Scott Williams, Laura’s ex-boyfriend.

Wurster and Matt Lukin of Mudhoney on tour in Europe, 1992.

Wurster examining Mudhoney’s van in Europe, 1992. The band traced “porno crew” into the road dirt.

Superchunk tour manager Dino Galasso, Mac, Wilbur, and Wurster in Europe, 1992. Wilbur is wearing the free pair of British Knights sneakers he earned when Superchunk recorded a song for a BK ad.

Laura after a good cry, 1990.

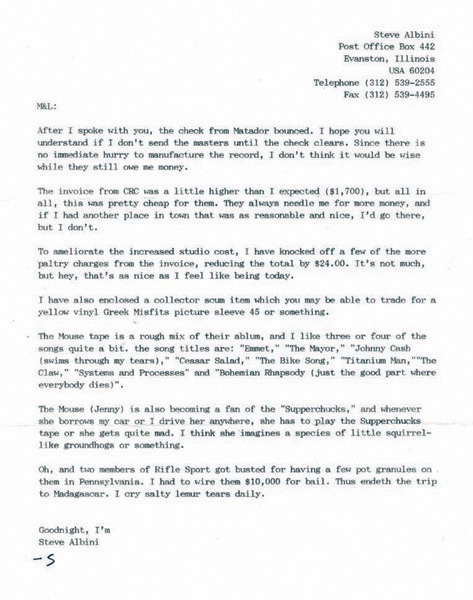

A 1991 letter from Steve Albini to Mac and Laura.

Laminate from Superchunk’s 1992 tour of Japan.

Superchunk in Europe, 1992.

Superchunk getting ready to sleep on the floor of Die Insel, a club in the former East Berlin, 1992.

New Zealand’s the 3Ds, the first non-U.S. band to release an album through Merge.

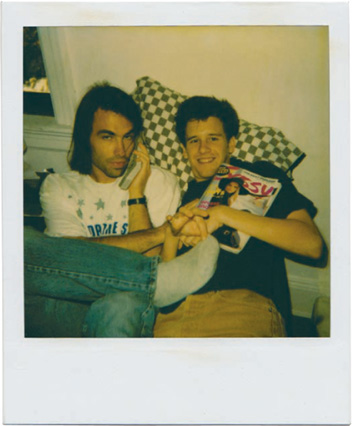

Phil Morrison and Mac in the early 1990s.

Wurster in Europe, 1992.

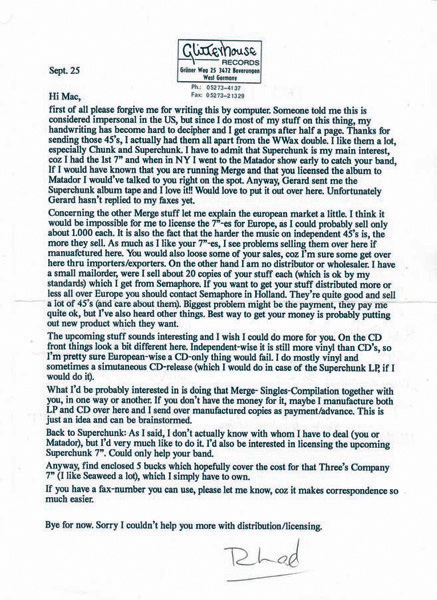

A 1992 letter to Mac from Reinhard Holsten, the co-founder of the German label Glitterhouse Records, declining to distribute Merge’s releases in Europe.

Merge newsletter, circa 1991.

Pen Rollings and Bobby Donne of Breadwinner.

Backstage deli tray, Munich, 1992.

Phil Morrison directing the video for Superchunk’s “Fishing” in a field behind Jon Wurster’s house in North Carolina, 1991. At right are Wurster and Pier Platters co-owner Bill Ryan at the same shoot.

Butterglory: Debby Vander Wall, Stephen Naron, and Matt Suggs in Lawrence, Kansas, 1995.

Raleigh’s Finger, 1990.

Our Heads, Butterglory’s second Merge release.