Stephin Merritt and the Magnetic Fields

In late 1991, Mac picked up a new 7-inch that had just come into Schoolkids. It was a release from Harriet Records, a Boston label founded by Harvard University history professor Timothy Alborn two years earlier. The A-side was called “100,000 Fireflies,” and it was a haunting, spare, and strange amalgam: An artificial tick-tock drum-machine beat beneath what sounded like a toy piano playing sugary melodies and a gorgeous, classic woman’s voice singing desperately sad lyrics with a delivery reminiscent of Petula Clark. It reminded Mac of a lo-fi, Motown-inflected Yaz, featured one of the most memorable opening lines ever laid to tape – “I have a mandolin / I play it all night long / It makes me want to kill myself” – and sounded like pop music from the distant future as it might have been imagined in 1965.

The band was called the Magnetic Fields. Mac had never heard of them, but he loved “100,000 Fireflies” and played it so frequently in the van on the road that Wurster suggested that they cover it. Mac had been thinking the same thing, and they came up with a version that swapped out the original’s delicate reserve for furious guitars and Mac’s urgent, strained vocal delivery. It quickly became a crowd favorite at shows; Superchunk recorded its version during the On the Mouth sessions in Hollywood and eventually released it as a B-side on a single.

Word eventually got back to the Magnetic Fields, then located in Boston, that some punk-rock band was playing their song. On October 22, 1992, Stephin Merritt, who wrote “100,000 Fireflies,” and his bandmate Claudia Gonson went to a Superchunk show at nearby Brandeis University.

Stephin Merritt I was horrified. It’s probably best if I don’t go into the details of why I was horrified. But we thought of punk rock as reactionary. We thought of punk rock as… Stalin.

Not that Mac himself is very Stalinesque.

Stephin Merritt No. More like Emma Goldman, maybe.

Thus began Merge Records’ relationship with the Magnetic Fields, which would last nearly a decade and produce one of the most memorable and audacious albums that any label had ever gambled on.

Merritt did not glad-hand with Mac and Laura that night at Brandeis. That task would be left to Gonson, the Magnetic Fields’ voluble drummer and sometime vocalist, who also doubles as Merritt’s manager.

Stephin Merritt I’m not into meeting people and all that.

Brandon Holley worked with Merritt when he was a copy editor at Time Out New York in the late ‘90s.

Brandon Holley That guy is such a morose motherfucker. I love him. We would bring trees around where he worked to sort of help the oxygen levels.

Merritt was, as he told the Village Voice in 1999, “conceived by barefoot hippies on a houseboat in St. Thomas,” and had a rather chaotic and unconventional upbringing. He never met his father, Scott Fagan, a folk singer from the Virgin Islands who recorded for RCA and ATCO in the ‘60s and ‘70s. His mother, a schoolteacher, raised him as a Buddhist and moved him around the Northeast; he likes to say that he lived in thirty-three different homes in his first twenty-three years. He started writing songs when he was four, having found the lyrical sophistication of Pete Seeger’s “Little White Duck” wanting and becoming convinced that he could do better. By the time he was fifteen, his mother saw enough musical interest on his part to make him promise that he would never become a professional musician. He attended a bohemian, progressive prep school in Cambridge, Mass., where he was encouraged to indulge his eccentricities (the unusual spelling of his first name is artificial; he saw a television program that recommended misspelling your name as a way to track which junk mail lists you’re on).

Merritt met Gonson when they were in high school in the mid-eighties. She was everything he was not – cheery, talkative, and interested in other people. They formed a band in high school with Merritt playing guitar and Gonson playing drums, called the Zinnias. When Gonson left Boston to attend Columbia, Merritt started a short-lived project called Buffalo Rome with Shirley Simms that resulted in a self-released cassette. In 1988, Gonson transferred to Harvard and tried to get Merritt to start up a new band with her. When he refused, she put together the Magnetic Fields and started playing all of his songs.

Claudia Gonson We were banging through the songs, like rock and roll, guitar strumming, just wrong on every level. And so Stephin instantly inserted himself into the band. He was like, “Okay, I have to do this because you guys suck and you’re destroying my music.” So he showed up and he took over.

Stephin Merritt I didn’t want to be in a live band. I don’t even want to see live music, let alone make it. But I said, “You’re not doing this well enough. You need my help.”

Merritt started playing guitar, and Claudia moved to drums. Merritt hated the sound of his own voice – an affectless baritone that recalls Beat Happening’s Calvin Johnson, only more in tune – and brought in assorted female vocalists, including Susan Anway of the eighties Boston punk band V;, who sang on “100,000 Fireflies.”

Merritt didn’t care much about independent music. His lodestars were ABBA, which he regards as the purest formal distillation of the pop aesthetic, and the Brill Building songsmiths. He was interested in writing and recording clever and beautiful pop songs. He didn’t care much whether they came out on an indie or a major, as long as they came out, and the process was convenient and at least somewhat remunerative. He had no particular love for indie rock or affinity for the burgeoning DIY community; Claudia, on the other hand, was an avid observer of the indie scene and seemed to know just about everyone in it.

In 1988, Claudia Stanton, an A&R rep for Capitol Records, offered the Magnetic Fields a demo deal, paying the band $2,000 to record some songs with the option of signing them if she liked them. Merritt recorded the songs that would become The Charm of the Highway Strip, a highly synthesized reimagination of country music. He sang the vocal melodies himself as a placeholder; when he gave Stanton the tape, he told her that the vocals would be sung by Anway in the actual recording. Stanton listened, and, in spite of his caveat, rejected it because she didn’t like Merritt’s deep voice. “I hate Johnny Cash,” she said.

Over the next few years, Merritt did a brief stint at NYU Film School and took courses at the Harvard Extension School, and the Magnetic Fields perfected their denatured, processed pop sound. Merritt recorded the band’s first proper album, Distant Plastic Trees, mostly by himself, in 1989. He couldn’t find a label in the U.S. to release it, but RCA Victor put it out in Japan, and an indie label, Red Flame, released it in England.

Stephin Merritt The major in Japan paid the indie in England, and the guy who ran Red Flame disappeared. With our 9,000 pounds. So we can be forgiven for not romanticizing the indie experience.

After Distant Plastic Trees, the Magnetic Fields entered what Gonson calls its “miasmal period,” in which they cast about for a label. There were the 7-inches on Harriet. There was the self-released The Wayward Bus, which the band packaged with Distant Plastic Trees on one CD. There was the House of Tomorrow EP on Feel Good All Over – “Horrible name,” Merritt says. “It makes me shudder just to think of it” – a Chicago indie run by John Henderson (who, with Peter Margasak, booked Superchunk’s first show there, at the Czar Bar). Henderson was one of Gonson’s indie-rock friends; his relationship with the Magnetic Fields was more a function of their shared love of the Raincoats than his prowess at selling records. By the time Gonson and Merritt saw Superchunk ruining their song at Brandeis, they had dealt with five labels in four years, and were ready to try another.

That wasn’t the first time, coincidentally, that Mac and Gonson had met: Though he didn’t put it together until that night, Gonson had approached Mac on the Columbia campus while they were both students there and tried to recruit him to appear in a short film she was making.

Mac It was supposed to take place on an airplane. And it was going to be all black and white, except for I would be on a plane eating mac and cheese, and the mac and cheese would be really bright orange.

The first Magnetic Fields record that Merge put out was a reworked version of The Charm of the Highway Strip, in April 1994. It came out almost simultaneously with Holiday, the band’s third full-length, on Feel Good All Over. That wasn’t supposed to happen: Holiday had been finished much earlier, but it took Henderson a long time to get it into stores. The twin releases meant that the records were reviewed in tandem, which irked Merritt, and that people were more likely to buy one or the other, but not both. Up to that point, both labels had been vying to put out Magnetic Fields records, but the delay in getting Holiday out clinched it. Feel Good All Over went out of business not long after.

Claudia Gonson The reason that Merge made sense was that it was an incredibly functional, stable, good business entity. We can talk about how we all liked music, and we were all in the same scene. But really, it’s a miracle. There are like five billion trillion labels out there that started and ran themselves into the dirt instantly, and ripped everybody off. And three or four of them worked with me, and I can tell you that they owe me money. What’s been amazing about Merge is this incredibly competent head that they have on their shoulders, combined with this sense of real friendliness. And a work ethic that says, If you treat people in a human way, we can come to understandings on almost anything.

Charm is what the robot cowboy played by Yul Brynner in Westworld might have listened to when he was feeling lonesome. It was a concept record about the open road, with lyrics that seemed to belong in a Lee Hazlewood album (“I’m never going back to Jackson / I couldn’t bear to show my face / I nearly killed you with my drinking / Wouldn’t be caught dead in that place”) swathed in clanking, metallic melodies. Merritt, who decided that he could live with his voice, after all, sang all the songs. He also designed the cover art, which featured a black background with yellow dashes in a line. Merritt was characteristically exacting about his designs, and the Merge logo—“Merge” in simple black lettering inside a box with “records” beneath – occasioned Mac and Laura’s first run-in with Merritt’s finicky side.

Stephin Merritt I don’t know who designed the Merge logo, but I refuse to apologize to them for saying that it’s butt ugly. It would have completely ruined the artwork.

He delivered the art for Charm with his own version that fit the record’s theme: A yellow road sign reading MERGE. Mac and Laura balked.

Mac We really wanted people to know that it was our record.

Stephin Merritt Right. Your name is a traffic sign. Your logo is a potato stamp. Someone designs a record cover in which your name is used as a traffic sign. You give them a hard time about it. That was my idea for a new Merge logo, which they should have kept.

Merritt’s unusual manner of speaking – pausing for awkward periods of time between thoughts – took some getting used to. Laura was convinced for a long time that Merritt hated her, but she came to admire his refusal to indulge in pleasantries.

Laura I had conversations with him where I know I just said the wrong thing, and he responded in a certain way, and I was just like, “Okay. I’m never talking to him again.” It intimidated me for a long time, but at a certain point I just realized, “No, it’s funny. I like it. The more droll he is, the louder I’m going to laugh.”

Mac A conference call with Claudia and Stephin is always pretty fun. Claudia and I will babble on, and then when it’s time for Stephin to answer something directly there’s usually a dramatic pause, and then a very concise answer. It’s kind of a special thing.

Charm was the first Magnetic Fields record that was widely and readily available in the U.S. Mac and Laura asked Merritt to tour to support it, but he refused, both because he hated touring and because the only performers on the record were him and Sam Davol on cello (Gonson was a member of the band but didn’t contribute to the recording) – a duo that wouldn’t translate well to the stage. A year later, in 1995, Merritt was suddenly everywhere. Merge released a new Magnetic Fields record, Get Lost, and reissued The Wayward Bus and Distant Plastic Trees. Merritt also released a side project called the 6ths on a major, London Records. The 6ths was a supergroup of sorts; Merritt wrote and recorded the songs, which were indistinguishable from Magnetic Fields songs, and sent them to various vocalists to sing. The first 6ths record, Wasps’ Nests (named for two of the most difficult words to pronounce in the English language) featured vocal turns by Mac, Lou Barlow, Yo La Tengo’s Georgia Hubley, Luna’s Dean Wareham, and other indie-rock luminaries.

Merritt liked keeping one foot, however tentatively, in the major-label world.

Claudia Gonson It wasn’t so much major versus indie. It was just catch-as-catch-can. It was a million little things, and they were all happening. And anybody who wanted to do it, we were like, “Yes! We’ll do that! It’ll be fun.” It was sort of a throw-it-and-see-where-it-sticks ethic.

But he also worried about being stuck in what he once called the “indie-rock ghetto.” He had set out to make unadulterated commercial pop music, yet somehow found himself found himself on a label that was being hailed as ground zero of a newly-minted genre of music that he didn’t care for in the least.

Claudia Gonson Stephin Merritt does not own a record by Pavement, or Sebadoh. He used to get really, really upset at being associated with indie rock, especially words like “twee.” He just really had his own specific desire of how he wanted to be out there. And he felt controlled by me and, to a certain degree, I’m sure, Merge.

Artwork and instructions for Get Lost and The Wayward Bus / Distant Plastic Trees.

An Indie Rock painted by Gonson for the Merge fifth anniversary fest.

Daniel Handler (Author, under the name Lemony Snicket, of the A Series of Unfortunate Events books; accordion player for the Magnetic Fields) There was a kind of cuddly camaraderie among so many bands back then. Everybody said that everyone else’s band was incredible. But Stephin has always been the kind of person, where, if you ask him what he thinks of the Spinanes record, he’s going to tell you. I think that it was kind of shocking to say, “Oh, Superchunk just sounds like a rock band.” That was, like, heretical.

Stephin Merritt I ridicule the ideology of the so-called indie-rock ethos. I have nothing to do with that, and I’m sorry that Mac and Laura do. No doubt they are completely insincere about it and are just using it to sell records. And I am not joking. Still, I could make only calypso music for the next hundred years, and win all of the calypso Grammys for the next hundred years, and still be found only in the indie-rock section of every store and online retailer. Probably if Claudia’s friends were all metalheads, we would be considered an eccentric metal band.

Gonson had her own brief diversion from the indie-rock ethos. In 1996, Danny Goldberg took over Mercury Records, where he hoped to mine the same vein that he had worked while he was at Atlantic. And he hired Gonson as an A&R rep. She had relationships with just about everyone in the indie world, she was in a cool band on a cool label, and she had just helped Merritt organize Wasps’ Nests, which was a veritable treasure trove of unsigned talent.

Claudia Gonson Danny said, “I hired you in for four reasons: Sebadoh, Sleater-Kinney, and Ani DiFranco.” There was a fourth band that I can’t remember. “You’re an indie-rock girl, you know how to get Lou Barlow on the phone. I want you to bring these people in.”

Gonson was at Mercury for two years. The assignment was ludicrous: DiFranco had virtually staked her career on not signing to a major label, and by 1996, Sleater-Kinney and Sebadoh had been thoroughly courted by majors and made their intentions clear.

Claudia Gonson My calls to them were very hard for both of us. They’d be like, “Hey, we know you! You’re the girl from the Magnetic Fields.” And I’d say, “Yeah, I work for Mercury.” And then it would be this awkward silence. I think they felt betrayed in some way. It was just not a comfortable experience for me. I remember running into Lou Barlow on Avenue A, and I said, “Oh my god, it’s so weird I ran into you! Because I just had this conversation with my boss, and he wants me to talk to you.” And he was just like, “I gotta go.” And he just sort of ran. It was a very creepy time.

The next Magnetic Fields record, 69 Love Songs, would deliver Merritt from the indie-rock ghetto. There’s a story that Gonson tells to help explain how 69 Love Songs came into being: In 1994, Merge asked the Magnetic Fields to play at their fifth anniversary celebration at the Cat’s Cradle. On the drive down from Boston, they stayed overnight in Washington, D.C. In the middle of the night, with the band members sprawled out across someone’s living room, Merritt sat up in the dark and shouted, “Indie Rocks!” The rest of the band wearily humored him as he explained: In the late seventies, pet rocks were a fad. So why not Indie Rocks? Or Soft Rocks? Or Punk Rocks? He went back to sleep. The next day, when they got to Chapel Hill, Gonson collected rocks from the parking lot behind the Cat’s Cradle, went to an art supply store, and painted up about twenty Merge Indie Rocks. She sold them for $1 apiece that night at the show.

Claudia Gonson So that’s exactly Stephin Merritt in a nutshell. He has these ideas, and he never thinks about executing them. For every idea he executes, he has three thousand that he doesn’t.

69 Love Songs was the rare one that he did execute. It’s the kind of record that has an origin myth: In January 1998, Merritt was drinking alone at a piano bar on the Upper East Side, writing songs. He was listening to Stephen Sondheim, and thinking not about love but about the American composer Charles Ives and his book 114 Songs, and – “Indie Rocks!” – decided that he would write a musical revue called 100 Love Songs. It would feature various performers singing a vast and comprehensive survey of every kind of song there is to be written about love, from country to punk to krautrock to Irish folk ballad, all to be penned by him. The idea was quintessential Merritt: A taxonomic and clinical take on the most intimate and emotional of subjects. It quickly dawned on him that such a musical would be a challenge to finance, so he downgraded the idea to an album of 100 love songs. When that proved excessively long, he trimmed it down to 69: A suggestive number that had the virtue of being visually appealing on an album cover.

Daniel Handler He got the idea at the same time I had the idea for Lemony Snicket. I said, “Oh, I just decided to write these thirteen books about terrible things happening over and over again.” And he said, “I’m going to write and record sixty-nine love songs.” So we both watched the other person’s career-changing moment happen. It was all in his tiny, tiny apartment and he was just working on it all the time. I would stop by and hear stuff or play stuff, and I remember that he had this glass of orange juice that he had been drinking the night before. And he woke up in the morning and he had another sip of it, and he was surprised that the ice was still in there. But it turned out to be bugs.

Merritt constructed a massive chart on his wall listing the songs – he ended up writing well over 100 – delineating their genre, instrumentation, and variety of love they addressed. There were last-minute substitutions and additions, and it ended with a series of mad dashes to the finish line. One day, all of Merritt’s friends would get an e-mail from him saying, “In ten minutes we’re meeting at Dick’s Bar because I’ve finished the album.” Two days later, they’d get another: “In fifteen minutes, I’m having a party because I finally finished the album.”

Ed Roche, Touch and Go’s label manager, often found himself saying the same thing over and over about how Merge spent its money. Eventually, Mac came up with a handy time-saver: Anytime you want to tell us about how we’re wasting money, he told Roche, just say, “Jiminy Cricket.”

Roche said Jiminy Cricket a lot. A 1996 fax from Roche to “Laura, Spott, Mac, and Jiminy Cricket,” for instance, patiently explained why the label shouldn’t be responsible for providing free copies of CDs to booking agents. It opened with: “Laura should be holding a ruler so that she can smack both Mac and Spott when they turn this into a joke.”

Roche was a stickler for numbers, armed with spreadsheets and formulas for projecting sales – an enforcer for Touch and Go’s austere approach to the business. Mac and Laura, on the other hand – well, mostly Mac – were obsessed with making the records look cool and special, and were inclined to indulge their artists when it came to packaging.

Ed Roche Their hearts were in the right place, but I can’t say their heads were. If we were spending money on a five-color print job for a CD booklet when a four-color print job would get the same results, I would point it out to them in the hopes of saving us, them, and the band money. But Mac would be like, “Didn’t you see how fucking great it looked?”

Many debates about costs played out between Mac and Laura first, with Mac usually advocating the more ambitious and riskier route and Laura in the bean-counter role.

Ed Roche If you wanted a rational answer, you called Laura. If you wanted an enthusiastic answer, you called Mac. Eventually, I just stopped calling Mac for business questions because I knew what he’d say. Whereas I’d call Laura and say, “Hey, if you just change this one thing, it’ll save you $150.” And she’d say, “I’ll talk to Mac; we’ll change it.”

One day in 1998, Gonson called Mac and Laura to tell them that the next Magnetic Fields record was going to be a sixty-nine-song, three-CD musical tour through American songcraft from Stephen Foster to the Ramones, accompanied by a seventy-six-page full-color bound booklet (Merritt’s idea) with photos and a lengthy interview.

Mac I knew it was going to be good, and I really wanted to hear it.

Laura I thought it was crazy! Crazy and backwards!

Ed Roche I told them there’s no such thing as a triple record.

Actually, Merritt had always assumed it would be a double album. It was Mac who told him that it would be physically impossible to encode that amount of music on to two CDs.

Stephin Merritt I said, “What are you trying to do to me, you fascist!? It has to be two CDs!” The “69” was supposed to be a visual palindrome. But of course he was right. And it still works out numerologically, because of the three and the six and the nine.

Mac and Laura didn’t think at first they would actually have to confront the unlikely prospect of trying to make money off of a three-disc set.

Stephin Merritt Everyone in the world, including Claudia, including all of the other members of the Magnetic Fields, including Merge, including my mother, thought that I was going to come to my senses after making, oh, twenty-three songs. But once I wrote one hundred songs, it became clear to everybody that this was going to happen.

Sure, the Clash had Sandinista! and George Harrison had All Things Must Pass, but they had enormous audiences. Get Lost, the Magnetic Fields’ previous release, had sold roughly 17,000 copies. There were plenty of people willing to part with $12 for a Magnetic Fields record, but how many would be willing pay $36? One of the reasons Merge didn’t wind up like Feel Good All Over or any other number of failed indies is that Mac and Laura let the hard economics of each release guide their strategy. That’s the only way you can make money when you’re selling 5,000 to 10,000 records on most releases. The major-label philosophy essentially amounts to gambling – you throw hundreds of thousands of dollars into a hundred different bands, in the hopes that one of them turns up Ace-King and covers the losses on the 99 others. The Merge philosophy was rational: Spend as little as possible on each release, and they’re all more likely to be winners. An elaborately packaged triple-record with a list price of more than $30 ran precisely contrary to that philosophy.

Claudia Gonson There was a general feeling at that point that Stephin had made a lot of records with them and they were doing fine. And he had this groundswell of energy behind him, and he made money for the label, so let’s see where this goes. But how could we do it so we didn’t take a bath? How the fuck are we going to do this record? That was a big worry.

Jim Wilbur 69 Love Songs? I just remember laughing. “You are going to be living under a bridge this time next year, my friend!”

Mac, Laura, and Touch and Go came up with a compromise, which Merritt accepted: They would release 69 Love Songs as three separate, independently priced discs, with a limited-edition 2,500 copy run of the three-disc and booklet set, as a sort of collector’s item.

Mac We had a connection to our bands, and we wanted to be able to do this cool thing. And sometimes it’s worth it to sacrifice the reality of the bottom line for art, just to have a cool thing. We’d print just enough of the limited edition so we could sell out of it, for the hardcore fans. And everybody else would just buy the single volumes.

69 Love Songs was released in September 1999. The sheer audacity of the project alone was a story in the music press; Merritt was featured on NPR, and made the cover of the Village Voice. Spin gave it a 10 out of 10. Voice critic Robert Christgau gave the record an A+. The New York Times hailed Merritt as a “contrarian pop genius”; it would eventually be ranked the best record of 1999 by Magnet, second best by the Voice’s Pazz and Jop Critics’ poll, fourth by Spin, sixth by the Times, and ninth by Rolling Stone. For a release party, the band performed the entire record, in order, over two nights to sellout crowds at the Knitting Factory. None of this surprised Mac and Laura. What did surprise them is that the limited edition sold out immediately, as did the individual volumes.

Trish Mesigian (Former Merge employee) Oh, it was a nightmare. I mean, it was a great nightmare. Everyone in the office was scrambling to get this record back out while it was still hot.

Stephin Merritt Nobody could buy it for six weeks. I was very happy that the initial run had sold out. I was obviously not happy with the amount of the initial run, or that it was taking so long to repress.

The problem wasn’t just about rushing more copies into stores to meet the demand. It was figuring out what, exactly, the demand was. The smallest number of booklets that it made economic sense to order from the printer was 2,500. Which meant pressing 7,500 CDs. Sure, the first batch had sold out. But would a second? Or third?

Corey Rusk That was definitely a rough one. It’s such a phenomenal story for the Magnetic Fields. How often in any band’s career is a three-album box-set package with a big fat book their breakout record that sold seven times as many as any of their previous records? We weren’t always right in trying to be the voice of reason. The limited edition was not the right call, because the box set instantly sold out and everybody was clamoring for more. And it took a while before we could get more box sets, because we had to figure out – yeah, these all disappeared; but what if we make 5,000 more, and there’s a demand for 500 of them and then it just dies? We were talking about spending large amounts of money on packaging for something you’re really not sure where it’s going to go. So it was bumpy those first few months with that record.

It got smoother. To date, the box set of 69 Love Songs has sold 62,500 copies; combined with the individual CDs, the record has sold more than 150,000 units. Sales spike each Valentine’s Day. Within three years, the Magnetic Fields were performing it, recital-style, at the Hammersmith in London with Peter Gabriel, and at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall as part of the American Songbook series. So much for the indie-rock ghetto.

Merge moved out of its one-room office over Armadillo Grill in 1996, and took up residence in a house along a divided highway in Chapel Hill (it happened to be next door to the house that Mac had lived in during his year off from college, nine years prior, where he and his friends had screen-printed boxes of evil i do not to nod i live). In 2001, Laura was riding her bike through downtown Durham, a formerly vibrant neighbor to Chapel Hill that had been devastated by the collapse of the tobacco industry, when she saw a FOR SALE sign on a yellow brick two-story storefront that had once been the Self-Help Credit Union. Flush with Love Songs cash, Merge purchased the building for $250,000, a transaction that was significant enough to merit stories announcing it in both the Durham Herald-Sun and the Raleigh News & Observer.

But the Magnetic Fields didn’t stick around long enough for Merge to buy another building. Merritt released three more records with Merge: one 6ths full-length, one EP by a side project called the Future Bible Heroes, and one soundtrack under his own name. But in 2002, the Magnetic Fields signed to Nonesuch, a division of Warner Music Group. Major labels had approached the Magnetic Fields many times during the years they were on Merge; Merritt was always willing to hear them out, but Gonson was mistrustful. But Nonesuch was the home of Wilco, Laurie Anderson, Nixon in China composer John Adams, and Phillip Glass.

Claudia Gonson The idea that we could have been on Nonesuch, in my brain, was like the idea that I could have been the president of the United States. It wasn’t a remotely realistic fantasy. And then suddenly there was just this strange moment of, Wow we can really do this. And I think Stephin was very excited by things about the None-such catalog. It’s been an important stamp for Stephin to feel that he’s a Nonesuch artist as well as a Merge artist.

The Magnetic Fields performing 69 Love Songs at the Lyric Hammersmith Theater in London, 2001.

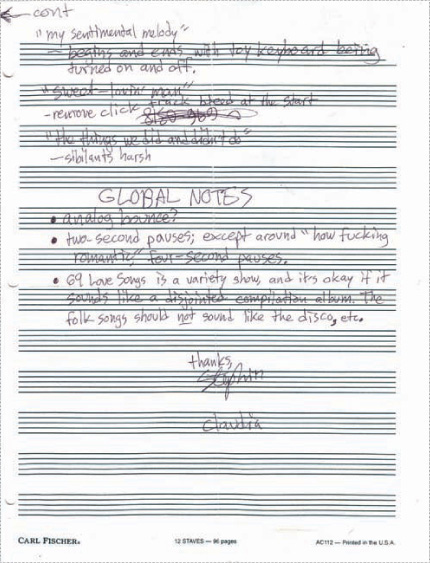

Stephin Merritt’s notes to the mastering studio for 69 Love Songs.

The story of the burgeoning star who abandons the indie that put him on the map is something of a cliché. But in the case of the Magnetic Fields, there is a rather cruel irony at play in the fact that Merge, with its scarce resources, undertook a relatively huge financial risk on behalf of 69 Love Songs, one that the executives of Warner Music Group would almost certainly never have tolerated. And if there is any release that proved that Merge was just as capable as a major label of making a record happen, it was 69 Love Songs. But there was no rancor in the departure.

Mac It made me sad, but they were very upfront about what they wanted to do, so we never felt betrayed when they moved on to Nonesuch.

Laura If a band wants to move on to a bigger label, they should do it. We don’t want unhappy bands on our label.

Claudia Gonson They were gracious as always. And I was pretty unhappy about having to sever a – it wasn’t really severed. I really don’t see it as an ending. It’s just more like having to put on hold the immediate relationship. But there was nothing really to say. They understood. But they said, “We have to warn you. It’s not what you think it is. You don’t have as much freedom.” So there was a sense of them kind of – sort of like talking to your older siblings. Like, “I know you want to fly and be free, but let me tell you, it’s not all it’s cracked up to be.” Which is true. Nonesuch are much more involved in the creative process in a way that I think Stephin has found frustrating. They ask him to do re-records, they ask him to change titles. They ask him to change artwork. There’s a whole different level of back-and-forth than we had with Merge.

Phil Morrison When the Magnetic Fields left, I told Mac and Laura, “Well, you have the greatest record they will ever make.” And I think that, so far, I’m still right.

Tom Scharpling A major label is not going to say, “Let’s put a three-disc set out of this thing.” Mac and Laura made something happen that wouldn’t have existed anywhere else. That’s the beauty of what Merge became, is that things like that were a possibility if they believed in them enough.

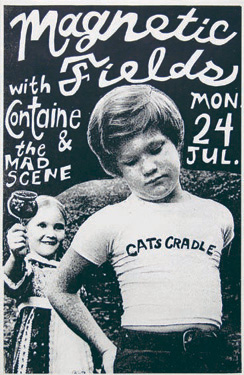

Poster by Ron Liberti, 1996.

Polaroid of Polvo taped by producer Bob Weston onto the interior of the box containing the master reels of Today’s Active Lifestyles.

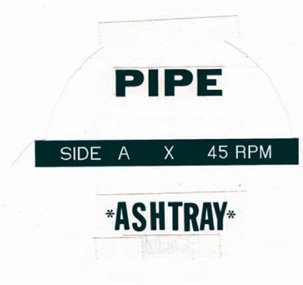

Original art for the label of Pipe’s “Ashtray” b/w “Warsaw” 7-inch.

Pumpkin Wentzel and Charles Gansa of Guv’ner.

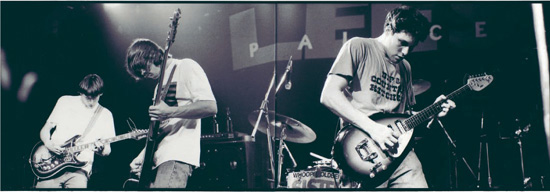

Polvo in Toronto, 1993.

Annie Hayden (Spent) and Sasha Bell (Ladybug Transistor; Essex Green) in New York.

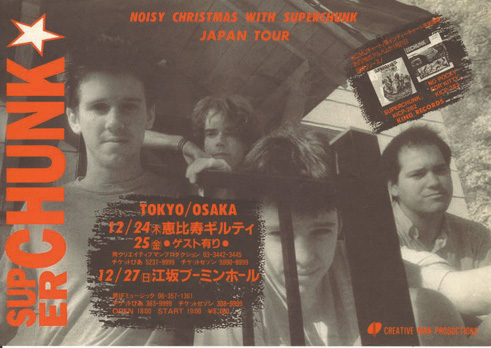

Flyer from the 1992 “Noisy Christmas with Superchunk Japan Tour.”

Wurster with dancers from the video for “The First Part,” 1994.

Pipe in Chapel Hill, April 1992.

Ash Bowie playing drums with Portastatic, Princeton, N.J.

Spent.

Stephin Merritt outside the offices of Spin in 1994.

A 1994 fan letter from Wilbur to Fred (F.M.) Cornog, addressed in error to “Frank.”

Wilbur at the Wet Behind the Ears kickoff dance party in Mac’s kitchen, 1990.

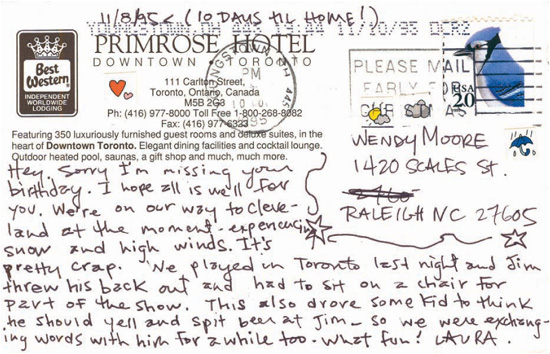

Postcard from Laura to Wendy Moore, 1995.

The Clientele in London during the making of Suburban Light.

Matthew McCaughan, Mac’s brother, during the recording of Portastatic’s De Mel, de Melão in Mac’s house, 2000.

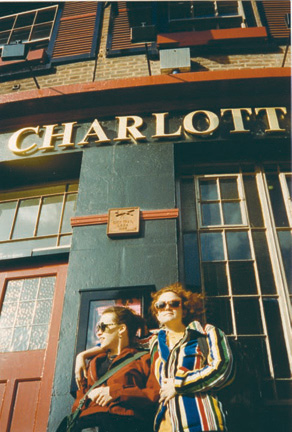

London, 1993.

Laura and Claire Ashby in England, summer 1993.

Promo photo from Here’s Where the Strings Come In, 1995.

Poster by Ron Liberti, 1995.

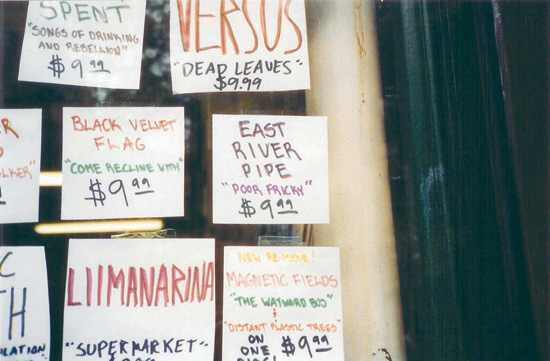

The window of Sounds, a record store on St. Marks Place in New York City, in 1995.