Spoon

Much of Britt Daniel’s life before Spoon consisted of Britt Daniel searching for people to start Spoon with. Daniel, a tall, gangly blond from Temple, Texas, grew up listening to Julian Cope, the Cure, and That Petrol Emotion. And he caught hell for it from most of the shit-kicking rockers at his high school. He knew he wanted to make music and always figured that once he got to college, he’d find like-minded musicians to play with who were desperate to sound like Wire or Gang of Four. It didn’t happen.

Britt Daniel I was struggling to find people who were like me. My best friend has a story about when I met him. It was our first week of college at the University of Texas, and he walked into a party, and I came right up to him and said, “Do you play an instrument?” And he said, “No.” And I was like, “OK, never mind.” And I went back and sat on the couch.

In Austin, Daniel started working at KVRX, the college radio station, and managed to cobble together a three-piece called Skellington that self-released three cassettes. But it didn’t go anywhere.

Britt Daniel They were the two guys that I could convince to be in a band. I taught the bass player from scratch. He was really into the Red Hot Chili Peppers. And the drummer was really into metal. Just trying to get everybody on the same wavelength, or even to learn the songs, was a struggle.

In 1993, Brad Shenfeld, a colleague of Daniel’s at KVRX, asked him to play bass in a country-rockabilly band he was starting called the Alien Beats. He declined, but reconsidered after realizing that he was in no position to turn down a chance to at least be in a band with a guy he liked. The Alien Beats recorded one 7-inch at the University of Texas’s student studio; when their regular drummer couldn’t make it, Shenfeld asked another drummer he knew, Jim Eno, to fill in for the session.

Britt Daniel He just came right in and learned the songs. I wasn’t used to dealing with musicians like that, who could remember that there’s a stop after this part, and that this part is a chorus, and this is a verse. It was very impressive.

Eno, a soft-spoken electrical engineer, wasn’t much of a rocker. He had gone to North Carolina State University and lived in Raleigh during the late eighties, but the roiling scene that Mac and Laura were navigating never made it onto his radar. While he’d played with friends, his first experience in a regularly convened band was as the drummer for the official jazz band of Compaq Computer Corporation, where he worked after he graduated.

Jim Eno The first time I ever played with them was also really the first time I played jazz. So I showed up in a conference room, which is where they would practice. And it’s a fifteen-piece jazz band, and there were charts, but I couldn’t read music at all. So they said, “Oh here’s a shuffle song. Go ahead and sit down. You can play this.” So I’m behind the drums and the horns are playing, and it sounds great. We get through to the end of the song, and all the horns stop. So I get up and I put my sticks in my bag, and I’m starting to walk away, and then the band starts playing again! I’m like, “My god, that was weird.” So I sit back down and start playing again, and then the band stops again. I’m like, “Okay, is everyone really going to stop this time?” And someone taps me on the shoulder and says, “Uh, Jim, you missed your solo.” The twelve-bar drum solo where I got up and all I did was pack my sticks up. They were like, “This is the most avant-garde drum shit I have ever seen in my life!”

Daniel and Shenfeld invited Eno to join the Alien Beats, which lasted a year before Shenfeld graduated and went to Los Angeles to attend law school (he is now Spoon’s lawyer). With Shenfeld gone, Daniel was once again in a position of trying to find musically like-minded people to play with; he begged Greg Wilson, whose insistent guitar playing in the band Sincola he admired, to start a side project with him. They called it Spoon, after a Top Ten hit in the seventies in Germany by the experimental band Can. Daniel wanted to play guitar and found a bass player, a woman named Andy Maguire, through an ad in the paper. They just needed a drummer.

Jim Eno Britt always calls it “the audition.” But he just called me and said, “Hey, I’m writing these songs. I was wondering if you wanted to come over and try them out and see if you like them.” And they freaking blew me away.

Daniel had only written a few songs for the Alien Beats, and they were sort of New Wave country. But his Spoon songs were angular, astringent, erratic and fierce, full of unusual time signatures and song structures, sudden pauses and bursts of atonal guitar noise.

Spoon recorded a few songs to give to clubs, which they self-released as a 7-inch called The Nefarious EP in 1994. Nefarious got some play on KVRX, and Spoon started building a local audience. Austin has always been a music town – it bills itself, after all, as the Live Music Capital of the World – but it was lousy with “next-big-thing” bands in the early nineties, owing largely to the success of Richard Linklater’s generational anti-manifesto Slacker, which was set there, and the rising prominence of the South by Southwest music festival as a showcase opportunity for unknowns to get the attention of major labels. Spoon was one band among many in Austin, and while their sound – which drew a lot of Pixies comparisons – attracted fans, they didn’t particularly stand out.

In 1994, South by Southwest rejected Spoon’s application for a showcase, so the band joined the bill at an antifestival show that March at the Blue Flamingo. They were up against Beck, who was playing at Emo’s on the same night, but Gerard Cosloy happened to catch Spoon’s set. Daniel didn’t pay too much attention to the music business. He had learned about Matador Records not from reading about Cosloy’s exploits in zines, or asking folks at the record store what the cool labels were, but from noticing that his favorite records – Liz Phair, Guided by Voices, Pavement – all had the same logo on the back.

They met Cosloy that night, and kept in touch with him. There was no talk of Spoon joining Matador’s roster at first; it was just friendly encouragement, with Cosloy helping Daniel set up shows in New York and Boston. A year later, Cosloy invited Spoon to play at Matador’s South by Southwest showcase as a “special guest” of the label.

Britt Daniel He was unbelievably helpful, and supportive. It meant a great deal to me mentally, in terms of believing in myself.

Wilson soon quit Spoon to spend more time with Sincola, and Daniel, Eno, and Maguire started working on a proper record as a three-piece in 1994, with Austin producer John Croslin. Croslin had been in the Reivers, a much-beloved but little-heard local roots-pop band that was signed to Capitol Records in the late eighties. Croslin had an eight-track in his garage, and Daniel persuaded him to record Telephono free of charge over the course of a few months in the spring of 1995, working nights after Croslin got off work from his job at a bookstore.

Early on, Daniel wore sunglasses onstage because he thought it was cool, and it’s a pose you can hear on Telephono. It was jittery and detached and shot through with hipster noir; the band’s goal was simply to capture the sound of a Spoon live show, but Daniel’s vocals were often treated with distortion and sung in an occasionally awkward drawl that drew attention to the artifice of studio production. It was self-consciously cool, and for better or worse, it did sound like the Pixies, and a little bit like Nirvana, and it had some of the ironic swagger of the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion. But every rock record is an exercise in accommodating and stretching the strictures of genre. And where Telephono hits all the indie-rock buttons, its songs have a discipline and a restlessness that take nothing in the rock songbook for granted. “Nefarious,” for instance, reaches an infectious chorus within its first thirty seconds, only to swap it out for different lyrics and a different melody over the same chord changes on the second and third go-rounds, before returning to the original chorus on the last repetition. It sounded like a band struggling to figure out what a great record is supposed to be.

Putting a band together had been a constant struggle, but with Telephono in hand, getting a record deal was almost laughably easy. Daniel sent tapes to a bunch of labels, and the next thing he knew, Spoon was getting flown out to Los Angeles to meet with A&R reps from Interscope, Warner Bros., and Geffen. Daniel also sent a copy to Matador. Cosloy said he loved it, but didn’t make an offer. So Spoon heard out the majors.

Jim Eno People were feeding us lines about how great we were going to be.

Britt Daniel I knew there was something not to be trusted about the major-label system, but I wasn’t really sure what. They just seemed to either make a band really huge in a really cheesy way, or else not be able to succeed. And I didn’t really want to come out huge with our first record. It kind of scared me. And I wanted to be able to make records the way I wanted to, and not have someone come in and say, “This is great, we just need to have it mixed by” whoever the hot producer is at the time. And there were people who thought that was a great way of doing it. We talked to people who said, “This record is great, it just needs another $50,000 for the mix, and then it’s ready to go.” People would literally say that. And those were the people we couldn’t work with.

In the end, it was Geffen that made Spoon an offer. Under the guise of seeking his advice, Daniel made one more pass at Cosloy.

Britt Daniel I mentioned it to Gerard, like, “Do you know this guy at Geffen? He wants to put our record out.”

Cosloy finally bit, Spoon passed on Geffen, and Matador ended up releasing Telephono in 1996. It was in many ways an ideal situation: The record was already done, so Matador knew exactly what it was getting. And they were licensing it as a one-off deal, meaning Spoon would still own the master and wasn’t obligated to do its next record with Matador.

Telephono disappointed.

Britt Daniel It didn’t do so hot. It certainly sold a lot less than Matador was hoping. They lost a lot of money on it.

It sold fewer than 3,000 copies. Rolling Stone gave it two stars and said it should have been called Smells Like Doolittle. Spoon was dismissed as a Pixies knock-off.

The Pixies problem – those familiar boy-girl harmonies – had, ironically, already been solved in the least pleasant way imaginable: Maguire left the band before Telephono’s release and sued Daniel and Eno, claiming she cowrote most of the songs on the record and was entitled to royalties. The suit dragged on for nine months before it was settled, with Maguire getting a cut of royalties from radio play or other public performances of the record. Daniel and Eno recruited Croslin to fill in on the tour to support Telephono, and Spoon, bedeviled by legal troubles and dismal sales, hit the road.

Britt Daniel It was brutal. We kept going out, and going out, all year long. We’d play in Fargo to maybe three people, and one of them was pacing the floor like he had cabin fever and didn’t know that there was a band on stage. That was a real thing that happened. We played New York in front of sixty people, most of whom were there as guests of Matador. We were losing money. It was a grumpy and stressful mood on the road.

Jim Eno It was a pretty miserable experience. John was going through a divorce. And we would play a show in, say, Chicago, and there would be twenty people there. And the next time we’d come through, there would be forty. And the next time there would be ten. So it’s the third time you hit a city, and your audience is going down.

Daniel and Eno loved working with the people at Matador, but their dreams of a soft launch at a cool label weren’t panning out. It was closer to a nonlaunch. Matador’s publicity people couldn’t find a way to convince the press to write about Spoon, and when they did, it was usually to accuse them of being derivative, a tag that the label’s publicists couldn’t help Spoon shake. And the records weren’t getting into stores.

Spoon in the Elektra era: Jim Eno, Britt Daniel, Josh Zarbo.

Jim Eno So here we are touring our asses off, and there’s no press about us, and no one can get our records in the stores. No one knows we’re playing, which is why ten people show up. And if those ten people decide they want to buy our record tomorrow, they can’t.

Eno’s final straw with Matador came in St. Louis, when, “to try not to have a nervous breakdown,” he took a walk before the show and wandered into a record store. He found a record by labelmate Tobin Sprout in the store’s listening booth – a coveted spot that labels can land for their artists either through persuasion, discounts, or cash payments – and no Spoon records anywhere in the store.

Jim Eno Tobin Sprout had never toured. So why didn’t Spoon have a listening booth in St. Louis?

Daniel and Eno regrouped after Telephono, releasing the five-song Soft Effects EP—a loose, classic-rock-inspired departure from Telephono’s rigidity featuring “Waiting for the Kid to Come Out,” which The New Yorker would later call “the first great Spoon song”—through Matador in 1997. The same year, they brought in Josh Zarbo as a permanent bass player, from the Denton, Texas, band Maxine’s Radiator. When they began work on their next full-length, A Series of Sneaks, their options were wide open. They did it the same way they did Telephono, funding the recording themselves and working with Croslin, this time at various professional studios around Austin.

For a band that was somewhat demoralized by a less than stellar debut, Ron Laffitte, the general manager of the West Coast office of Elektra Records, seemed like a godsend. Elektra sat out the flurry of major-label attention paid to Spoon before Telephono, and after looking at the record’s sales figures, the other labels that had been so convinced that Spoon was going to be huge quickly changed their minds. When Laffitte heard Telephono, he fell in love, and became convinced that Elektra could – with an investment of time, patience, and money – make them stars. The label had a long history of finding and developing bands who were outside the mainstream, like 10,000 Maniacs, Stereolab, and, appropriately enough, the Pixies. And what’s the point of working at a major label if you can’t find bands that you love and make them stars? Laffitte romanced Spoon. He went to shows, and called their manager and lawyer on a weekly basis to demonstrate his commitment. He literally wouldn’t leave them alone.

Ron Laffitte They were too good not to be signed.

Britt Daniel He really came after us hard. Which played well.

Daniel and Eno knew that Matador wasn’t working, but they still feared working with a major. They were worried about getting dropped if the record didn’t do any better than Telephono. They were worried about getting the support they needed to push them to radio stations. They were worried about working with people who didn’t really care about the music that they loved. They didn’t know what to do, and entered into agonized negotiations with Laffitte. He understood their hesitations, and he promised them that he would get them what they needed. He called Daniel every day to talk it through.

Britt Daniel We weren’t babes in the woods. We knew what the risks were. And he was very aware of that, and tried to soothe those concerns. And he seemed to genuinely like Spoon. And I bought it.

Ron Laffitte Britt was a lot more sophisticated than I anticipated. He had a very good understanding of the pitfalls of signing. Frankly, I think he had a better view of it than I did. My view of Elektra at the time was unrealistic, and a little romantic about how much time and energy the label would invest in a band like Spoon.

Spoon signed to Elektra for a “firm” three-record deal. It seemed remarkably low-risk from the band’s perspective: A Series of Sneaks was already in the can, so the label wasn’t going to meddle with it. They’d put Laffitte through the wringer and he answered every question the right way. They even made Elektra chief Sylvia Rhone – the one who said Lou Barlow didn’t “have what it takes” – offer her assurances that she would stick with them if A Series of Sneaks went south.

Britt Daniel We said, “If the record doesn’t do so well at the beginning, then what do we do?” And she talked about working it long-term and going back and doing that second record and getting you on opening tours and making it work at radio or press. All this record-biz talk.

Daniel, Eno, and Zarbo didn’t indulge in their major-label status, earning them a reputation at Elektra as charmingly naïve penny-pinchers.

Britt Daniel We were really rational about it. We did things like take a bus home instead of a flight so that we would save money for them. When we laid out our budget for the tour, we said, “We don’t need per diems. Never had them before. Those are for people who make money.” Elektra said we had to take them. But there was a lot of goodwill there. They couldn’t believe we were such team players. At least that’s how it was presented to me. They were probably thinking, “These guys are boneheads. They’re doing it small-time.”

Eno first got a sense that something was amiss when the label picked the minute-and-a-half song “Car Radio” as the single, and asked the band to make it longer.

Jim Eno I think it’s probably the first time in the history of music that a band was asked to do a radio edit to make a song longer. We didn’t want to seem like a bunch of assholes, so we sat in front of a digital editing system for a couple days and did it. We were going to just take thirty seconds from the chorus of a Third Eye Blind song and pop it in. That would have sounded good.

The length didn’t matter. A Series of Sneaks was released in May of 1998. It got excellent reviews compared to Telephono; its wiry, compressed, antic songs – only two of which made it to the three-minute mark – earned it 9.4 stars out of 10 from Pitchfork. Elektra waited months, while Spoon toured all summer, to push “Car Radio” to radio stations. Major labels select specific time frames to push songs to radio by calling program directors and hyping the song. If it picks up some steam, they keep pushing it. If it doesn’t, they move on to the next release. Elektra decided to push “Car Radio” during the week that the radio promoter responsible for Spoon was on vacation. It made it into rotation on one station.

At the time, Elektra was in the midst of a remarkable string of hits, with Third Eye Blind, Busta Rhymes, and several other bands on the label hitting the charts. Spoon and its off-kilter, decidedly noncommercial record suddenly looked like small ball to the people in Elektra’s New York headquarters, and Laffitte, in L.A., found himself unable to get the company to devote much attention to it. He stopped returning Daniel’s calls. He didn’t come to any of Spoon’s shows. Elektra didn’t pony up for the promotional budget Laffitte had promised. He was ashamed that he couldn’t live up to his word, and was busy engineering his exit from Elektra.

Ron Laffitte I made a lot of promises to the guys in Spoon that were based on what I believed would be my ability to dig in and stay the course with a band that would eventually be able to break down the walls. I thought I could keep those promises, and as it unfolded, I realized I wasn’t getting it done. I went underground a bit. I did a disappearing act.

Sneaks sold about as well – or as poorly – as Telephono. Laffitte left in September for an A&R job at Capitol Records. Elektra dropped Spoon the same week.

Jim Eno Our manager called us and said, “You’re dropped.” I said, “They can’t drop us! We have another firm record in the contract.” Well, one thing you learn is that a firm record doesn’t mean shit. They can do whatever they want. It’s ridiculous. When you sign to a major, you’re really worried about getting dropped, because all your friends have been dropped. So what do you do? You talk to your lawyer and negotiate for six months to get two firm records. That’s how you can guarantee you won’t get dropped. Well, no. Not really.

Britt Daniel I felt like a fool. The very things that I had been striving to not let happen to the band happened, and they happened in a worse way than I could ever have imagined.

After he got fired, Laffitte called Daniel to apologize for not living up to his end of the bargain, and to express his desire to support Spoon in any way he could going forward. Daniel told him, “You can fucking forget that. We’re never going to work together again.”

Ron Laffitte It didn’t go well. It was a bummer. I blame myself.

It was during the tour for Sneaks that Mac first saw Spoon, when they played at the Lizard and Snake in Chapel Hill. Mac wasn’t a huge fan of Telephono; the songs didn’t grab him, and the cover art, which featured a black-and-mustard photo of a guy in Jackie O. shades, had an “asshole quality” that put him off. But at the Lizard and Snake, they were great.

Mac Britt was playing an acoustic guitar, but plugged in and fuzzed out. There weren’t a lot of people there, but they sounded like a power trio, way beyond Telephono already. That turned me around on Spoon in a big way.

Jim Eno Britt and I recognized Mac in the crowd. We were excited that he showed up, but he was right up front, alone, and he left after three songs. We thought he hated us!

The Sneaks tour included a leg opening for Harvey Danger, a Portland band that was at the time enjoying its briefly ubiquitous Top 40 hit, “Flagpole Sitta.” But after getting dropped, the band was unsure whether to carry on with the tour, now that, without support from the label, they were likely to end up losing money. They decided they couldn’t pass up an opportunity to open for an act that, at the time, was selling 20,000 records a week based on the strength of their single’s radio play. Shocked to find that Harvey Danger was, however, drawing just two hundred people a night, they bailed out three-fourths of the way through the tour, exhausted and embittered.

Daniel thought the band, and his music career, was over. He moved to New York and got a job as an administrative assistant at Citibank.

Britt Daniel I didn’t think I’d ever be able to make records. Getting dropped as a baby band on a major was like the kiss of death. It felt like things could not get any lower.

One day, he suffered the ultimate indie-rock humiliation when he ran into Janet Weiss, the drummer for Sleater-Kinney, on his lunch break while wearing his work coat and tie.

Jim Eno I thought it was just a bump in the road. Britt’s a great songwriter. It was a huge hit to our ego, but we never had the discussion where we were just going to hang it up.

Daniel has described the post-Sneaks years as a “lost period.” His uncertain future had a dramatic effect on his songwriting. There was no new record to write for, no career to think about, no more idea of what Spoon was supposed to sound like. He expanded his musical tastes beyond Wire and Gang of Four to Elvis Costello, and Motown, and soul.

Britt Daniel The pressure was off. I was just writing them for myself. I doubted we’d ever record them. Maybe we’d play them live or something. So I stopped trying to be indie-rock cool, or play by the rules of what I thought good bands did, or post-punk bands were supposed to do. I felt vulnerable, and that was starting to come out. And I was doing things that I hadn’t had the guts to do before. I just felt like, well, if I want to have a piano on a song I can have a piano on a song. Fuck it. Nobody’s going to hear it anyway.

It was an off-hand exchange that turned things around for Spoon. They were playing a few shows with the Archers of Loaf and At the Drive-In, and brought along their friend Hunter Darby for the ride and to serve as tour manager. Musing about the Elektra situation, Darby said, “Ah, the agony of Laffitte.” Britt decided that had to be a song title, and another friend came up with the companion title of “Laffitte Don’t Fail Me Now.”

Britt Daniel And there we had it, you know? These songs had to happen. They were too funny not to.

In June 2000, Spoon released “The Agony of Laffitte” b/w “Laffitte Don’t Fail Me Now” as a 7-inch on Saddle Creek Records. The songs were not novelty tunes. Eno describes them as “two of the most bruising, emotional songs I’ve ever heard.” They dissect Laffitte with the icy bitterness of a jilted lover, playing on Laffitte’s sense of himself as a good-guy defender of artists at a label run by Rhone, whose loyalties lay elsewhere. “All I want to know is / Are you ever honest with anyone?” Daniel asks on “Laffitte Don’t Fail Me Now.” On “The Agony of Laffitte,” he sings, “It’s like I knew two of you, man / One before and after we shook hands.” Musically, the songs were a far cry from the intense angularity of Spoon’s previous records; they were closer to Lindsey Buckingham than Black Francis.

The spectacle of a great, and wronged, band issuing a kiss-off to a major label was what it took for the press to finally show a serious interest in Spoon, and the single sparked a round of stories about the failings of the major-label system. “Something went wrong, terribly wrong, with Spoon,” wrote Camden Joy in the Village Voice. “Before their imminent classic Sneaks ever had its chance to be ‘worked,’ some god gave them the finger.… Of course, it’s not just Spoon; [e]veryone who looked or sounded ‘alternative’ suddenly couldn’t summon up enough sales to make big the eyes of the bigwigs. Spoon, for one, were not surprised, but that doesn’t mean they weren’t hurt.” Laffitte became a symbol of the avarice and short-sightedness of the music business and was beset by questions about the songs from colleagues.

Ron Laffitte I guess it was fair. What happened to them was not fair, and I was responsible. I made a mistake that affected these people’s lives. Spoon is one of my favorite bands, but I didn’t spend a lot of time listening to those songs. I wish they hadn’t been written.

It took a while for Spoon to get back in the studio. Daniel was still unsure about his future, and Eno set about building a studio in his garage in Austin so they could record cheaply and at will.

Jim Eno It was difficult. I had a job, but Britt had a lot rougher times than I did when it comes to financials. I was using the money to help the band. He was trying to eat. I was trying to figure out how we could do it at my place and make it cheap, and trying to get Britt excited about recording his songs.

Buoyed by the press and antiestablishment goodwill attending the release of “The Agony of Laffitte,” they set about recording Girls Can Tell over several months in 2000.

Britt Daniel I didn’t know what would happen. I figured I was out of the record-making club at that point, but I was going to try anyway.

Girls Can Tell is a record by a band that has figured something important out. Daniel’s new unselfconscious approach to songwriting was matched by a drastically different sound, swathed in reverb, pianos, Mellotrons, and vibraphones. Gone were the onstage sunglasses, the antsy rock guitars, and the affected vocals. They were replaced by patient grooves, Motown hooks, and Daniel’s studied crooning and laid-back falsetto. Eno’s forceful and restrained drumming came dramatically to the fore; with Girls Can Tell, Spoon became masters of artfully delayed satisfaction, constantly walking the songs up to and back from the brink of indulgence. They made the record with the help of Austin producer Mike McCarthy, who likes to wear business attire in the studio, a habit that the band picked up. You can hear it on Girls Can Tell; it’s a record made by people dressed for work.

Mac There’s something about that record that’s so classic-sounding. Not as in classic rock, but literally classic: I’ve been in bars when that record comes on, and for the first millisecond before I realize it’s Spoon, my brain flashes through the Rolling Stones, Elvis Costello, the Psychedelic Furs. It’s so stripped down and elemental that it sounds like it could be almost from any rock era. It’s really the perfect album.

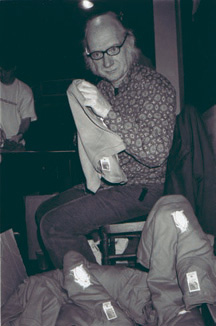

Superchunk soundman Jason Ward and Britt Daniel on tour, 2001.

No one wanted it. Spoon still had a manager and lawyer in L.A. who were shopping it around, and Daniel would sneak out of work to the pay phone of the Marriott Hotel in Times Square for status updates, because it was the closest quiet place to conduct conference calls.

Britt Daniel Every month it would be the same thing. Nothing was happening. I thought it was the best thing we’d ever done, and no one was interested.

Daniel had had high hopes for Merge – he knew that Mac had been at that show in Chapel Hill – and sent him an early version of the record, but never heard back. But Jim Romeo, Spoon’s booking agent, also booked Superchunk, and made sure Mac listened to the final version. He loved it. Laura took convincing.

Laura I had never really listened to Spoon before Girls Can Tell. When I first heard it, the working title was French Lessons. I actually got pretty attached to that title. But my immediate reaction was, “This is too catchy for Merge.” I could see frat boys wearing their hats backward digging that record. For some reason, that freaked me out. I had not yet come to accept and appreciate the back-hatters of the world. But it sounded great, and the songs were catchy as hell, and once they got in my head, there was no escape. So I came around. Once word got out that Merge was putting it out, people started coming out of the woodwork to tell us how excited they were.

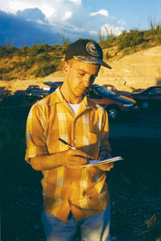

Jim Eno with a fan in Florida, 2001.

Finally, Mac called Daniel in the summer of 2000 and, apologizing for taking so long, told him Merge wanted Girls Can Tell. Merge was the only label that expressed real interest. It released Girls Can Tell in February 2001, and sold an astonishing 20,000 copies, more than Telephono and Sneaks combined. NPR did a feature on Spoon, its major-label travails, and its indie rebirth.

Britt Daniel For the first time, we put a record out and our expectations were not completely crushed. Things were working. Press was happening, the records were in stores, it was on college radio. And we were dealing with people at the label that didn’t make you want to take a shower after hanging up. It was a dream come true.

Merge was able to sell four times as many copies of Girls Can Tell in the first six weeks after its release than Elektra was able to sell of Sneaks in a year. The tour for Girls Can Tell was Spoon’s best yet.

Jim Romeo They played Maxwell’s in Hoboken in 1999 or 2000, and they drew four people. And then literally a year and a half later they sold it out in advance.

At one point on the tour, Eno recalls, they were making their way toward New York, where they had a show booked at the Bowery Ballroom. The day after that show was scheduled as a day off, but they’d kept a hold on the Bowery so that, in the unlikely event the first show sold out, they could add another.

Jim Eno Every day, as we moved closer to New York, we would wake up and look at the presale numbers. And this tension was building as we made our way. We ended up selling both nights out.

Eno got a lesson in indie-label accounting when he received his first profit-split statement from Merge. Given the sales of Girls Can Tell, he was expecting a good-sized check, but it was for $6. What he didn’t understand was that a $6 check meant that the record had already earned out – Merge had made back all the money it spent on the advance and on producing and promoting the record, plus $6. On every statement thereafter, Spoon would get half the money made on every record they sold. The checks got significantly bigger.

Jim Eno I was talking to this guy in a major-label band, and he was telling me about how they had to audit their label’s books, and they found a $1-million math error. I was like, “Well, we just got our first statement from Merge, for $6.”

After Girls Can Tell, Spoon went on an unrestrained tear of great records and good luck. In 2002, Merge released Kill the Moonlight, a piano-and-drums-heavy masterpiece that made dozens of year-end best-of lists and was named one of the Top 100 indie records by Blender. The single, “The Way We Get By,” a propulsive and infectious ode to living poorly – “You sweet-talk like a cop and you know it / You bought a new bag of pot / So let’s make a new start / That’s the way to my heart” – was featured on the soundtrack to The O.C., which had at the time captured the minds, hearts, and ears of the fourteen-and-up set nationwide. Daniel was featured in Time under the headline, “These Guys Just Might Be Your New Favorite Band.” It was the first time Merge had penetrated so deeply into the mainstream – it’s also the sort of placement major labels used to have a lock on – and it pushed Kill the Moonlight to 143,000 in sales.

Three years later, Gimme Fiction debuted at number 44 on Billboard, Merge’s first entrance into the Top 100, with 160,000 copies sold. Entertainment Weekly described it as brimming with “classics-to-be.” The single was a booty-shaking vamp worthy of Prince called “I Turn My Camera On” that sounded almost nothing like anything Spoon had done before, and it became their calling card. Merge hired Karen Glauber to work it to radio, and it began to get enough commercial play to make a crucial jump.

Karen Glauber The difference with “I Turn My Camera On” getting radio play was, at Spoon shows you’d all of a sudden see these mainstream girls start doing sorority-girl stripper dances to it instead of the indie-rock head-nod. It’s a totally different level. The beer-up-in-the-air kind of thing. You just know when something’s a hit.

“I Turn My Camera On” also found listeners through a lucrative and decidedly nonindie side business: It was the soundtrack to a Jaguar commercial. There was a time when the notion of even classic, major-label rock being used to hawk cars or shoes was considered unconscionable. When Nike licensed the Beatles’ “Revolution” from Michael Jackson, who owned the copyright, for use in a 1987 advertising campaign, it caused an uproar. The Beatles sued, furious that their song was being used to sell shoes. Bruce Springsteen turned down an offer from Chrysler of $12 million for the rights to use “Born in the U.S.A.,” and Neil Young decried the practice in “This Note’s for You.” So there’s no small irony in the fact that the past decade has seen a boom in using indie-rock songs in commercials. Eager to find something that sounds new to help their products cut through the televised clutter, advertisers have turned to bands, like Spoon, that haven’t been played to death on commercial radio. And indie labels and bands have come to rely on the business as an acceptable and almost integral stream of revenue.

When Superchunk was approached by British Knights, a sneaker company, in 1991, it was different. A friend of theirs in the advertising business was working on a commercial for British Knights, and explained to them that if they declined to license a song, the company would just find a soundalike. So they agreed, but found the notion of allowing one of their existing songs to be used to sell shoes so distasteful that they actually went into the studio to record a new “Superchunk-sounding” instrumental, called “Tasty Shoes, Tasty Shoes.” They were paid $1,000, a couple British Knights baseball caps, and a pair of sneakers for each member, and earned the ire of the few fans who actually saw the ad. Today the pay is much, much better, and the ire is almost nonexistent.

Laura Now I want a Jaguar commercial.

Matt Suggs One way a lot of bands are able to make a living doing what they do is selling their shit to advertising. I never would blame a band for doing something like that. It’s like a happy medium; you could stay on an indie and have complete control of what you’re doing, and maybe sell a song to a big advertiser. On the flip side, I can see why it’s kind of lame.

Jim Eno We’re paying the bills, you know? I know artists who are on smaller labels than Merge that get licensing, so it does seem like the mentality is changing. They’re embracing smaller artists. You don’t have to sell 250,000 records and have a Top 10 hit to get in ads. I know bands that sell 5,000 records and get some pretty good placements.

Aside from the Jaguar ad, Spoon has licensed “My Mathematical Mind” for use in an Acura ad, though they’ve turned down many offers, including one from Hummer. Those two car ads, which were in heavy rotation, served as the best exposure Spoon has ever had.

Corey Rusk Repetition is what gets people used to something. Music that might have sounded too far left of field to your average person fifteen years ago, now you start hearing that sort of thing in music on TV or commercials, and it becomes more familiar and acceptable to them, and they’re more interested in buying it. And that leads to bands that fifteen years ago wouldn’t have sold these quantities of records being able to now.

Karen Glauber It has opened up the consumer’s brain. It’s a lot easier to hear something, and they can Google it and figure out what it is and just buy it on iTunes.

Of course, once Spoon became a phenomenon (in spite of, rather than because of, their decision to work with Elektra), major labels came calling again. The band rebuffed all offers, including one from Elektra – the band’s manager suggested that the A&R rep who made the call check their corporate history.

Karen Glauber I think their decision-making process is informed by the situation they went through before. There’s a level of confidence in working with Merge. They’ve put out consistently great records and they’re making consistently great music. So for them to start over on a major would’ve been, I think, a great mistake. They’ve done great by Merge, and Merge has done great by them.

Corey Rusk Bands who had the major-label experience that didn’t work out are far more likely to stay out of the major-label system if they get a second chance later on and are making music that people are reacting to. They know they can make it work outside of it, and they know how volatile it is within it. I would contend that Spoon wouldn’t be selling any more records on a major, and would probably be making less money.

And their next record, released in 2007, almost certainly wouldn’t have been named Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga. You can almost hear the label executive objecting, “DJs aren’t going to say it!” The title, which came from Daniel’s onomatopoeic mimicking of a piano riff on its second song, was among a list of titles Daniel e-mailed to Mac for his input. “He said that was the one he liked the best,” Daniel says. “That is literally what happened.” Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga, a rollicking record full of joyful horns and blue-eyed soul, debuted at number 10 on the Billboard Top 100 in July 2007, and has sold 300,000 copies. Rolling Stone gave it four stars and included it in its Top Ten records of the year. Spoon – which now included Robbie Pope, who joined the band in 2006 after Zarbo quit – appeared on Saturday Night Live, Late Night with David Letterman, and The Tonight Show with Jay Leno. In terms of sales and promotional reach, it was in no way appreciably different from a major-label release.

The single, “The Underdog,” a danceable Van Morrison–esque tune, perfectly sums up Spoon’s relationship to the major label system: “You have no fear of the underdog / That’s why you will not survive.” Daniel initially didn’t want it on the record, but Glauber convinced him that it was the best shot for a single.

Karen Glauber I give Britt credit for trusting me enough. I was like, “Dude, I’m going to be the one in the trenches working your record.” I thought that it would do really well, even though it had horns. And modern rock doesn’t have horns. In modern rock, we’ve gotten to the Top 20, which is ginormous because we haven’t really spent money. You have to spend money at a certain point to get a record to the Top 20, and we weren’t willing to do that.

Spoon’s story – two overlooked records followed by a series of breakthroughs that built from release to release – was unremarkable twenty years ago. It was how the major label system was supposed to work. Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J. and The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle were not commercial successes, but they were the records that Bruce Springsteen made on his way to making Born to Run. They were investments that his label made in the hope of an artistic and commercial payoff, and they worked. Spoon was on the verge of their Born to Run when shortsightedness almost killed the band. Daniel and Eno took Mac and Laura’s faith in them just as personally as they took Elektra’s scorn.

Jim Eno It’s just so nice after a tour to get an e-mail from them asking if it went well. They’re just really sweet. It’s so rare in the music business to get that.

Eno finally quit his day job just a few months before Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga came out – in other words, two years after Gimme Fiction cracked the Billboard charts.

Britt Daniel Whenever I thank Mac and Laura for taking a chance with us, which has completely changed my life, they always say, “You did all the work. You made the records, and you did all the touring.”

Daniel has never spoken to Laffitte about the songs that he inspired. But he was happy to hear that, around 2002, his friends in a fellow Austin band called the Faint were being courted by Capitol Records, and Laffitte was the one doing the courting. They agreed to meet him for lunch in Brooklyn, and Andy Slater, the president of the label and Laffitte’s boss, joined them. They showed up carrying a copy of “The Agony of Laffitte” and handed it to him across the table. The Faint didn’t sign to Capitol.

Jim Eno They got a good lunch out of it, though.

Wurster sleeping in the van during Superchunk’s 1998 tour of Brazil.

Poster for Butterglory’s 1996 European tour with Guv’ner and Cat Power.

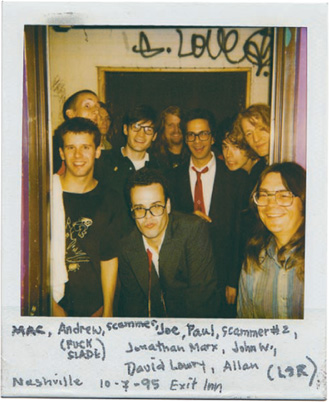

Backstage Polaroid of Superchunk and Lambchop by Annie Hayden.

Superchunk at the Great American Music Hall, San Francisco, 1999.

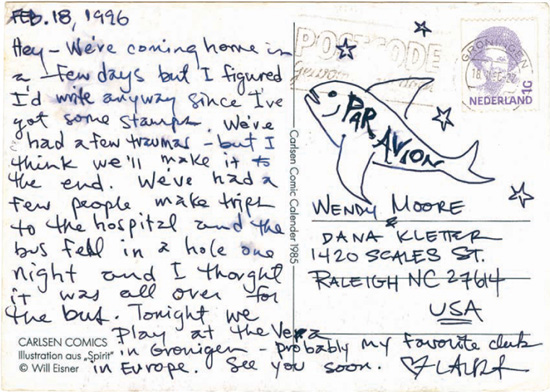

Laura’s postcards from the road.

Wurster in Australia, October 1994.

Neutral Milk Hotel, Columbus, Ohio, 1996.

Laura with Neutral Milk Hotel, 1998. From left: (Unknown), Scott Spillane, John D’Azzo, Laura, Jeff Mangum, Jeremy Barnes.

John Woo and Claudia Gonson of the Magnetic Fields, 1996.

From left: Tom Scharpling, Mac, Jonathan Marx (Lambchop), Laura Cantrell (Bricks), Kurt Wagner (Lambchop), and Paul Niehaus (Lambchop), Merge office, 1994.

Butterglory video shoot, 1995: Roman Coppola, Matt Suggs, Debby Vander Wall, Stephen Naron, Mark Fay.

Aggi Wright (The Pastels), Mac’s wife Andrea Reusing, and Wurster in Mallorca, Spain, 1997.

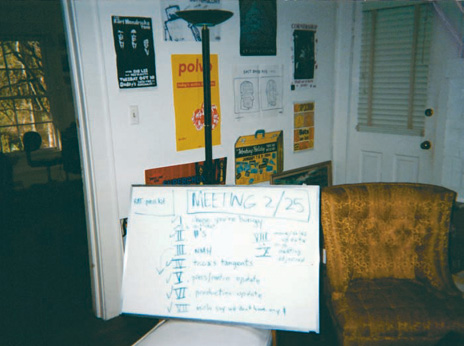

Merge meeting agenda. Item VII: “Mirla [Merge’s accountant] says we don’t have any $.”

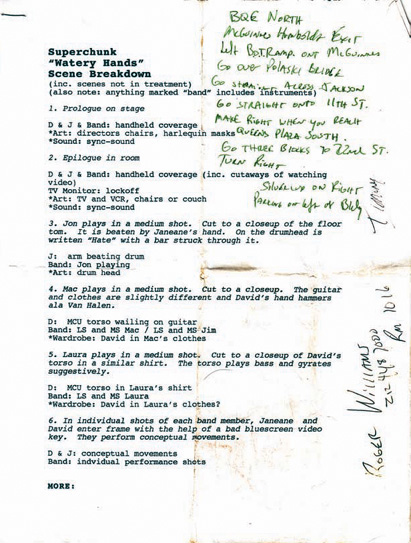

The video shoot for “Watery Hands,” directed by Phil Morrison and featuring Janeane Garofalo and David Cross, 1997.

“Watery Hands” video treatment by Phil Morrison.

Pier Platters co-owner Bill Ryan handling Superchunk merch.

Wilbur at the “Watery Hands” shoot, being wheeled by Damon Chessé (left) and David Doernberg (right).

Claire Ashby, Corey Rusk, and Laura in the photobooth at Lounge Ax in Chicago, Ill., on Laura’s birthday in 1998.

Sasha Bell (playing flute) and Gary Olson (playing trumpet) of Ladybug Transistor at the Cat’s Cradle during Merge’s 10th anniversary festival, 1999. Deanna Varagona (Lambchop) in glasses.

Party for Merge’s 10th anniversary fest. Clockwise from bottom left: Richard Harrison (Spaceheads), Matt Suggs, Brian Paulson, Patrick Buchanan (in baseball cap), Jonathan Marx (Lambchop), Chad Nelson (Touch and Go), David Doernberg behind him, Meg Fleischel (Touch and Go), Paul Niehaus (Lambchop, blurry at very back), Jaime Fleischel (short hair, in T-shirt facing right), Tom Reardon (baseball sleeves), Geoff Abel (Capsize 7, striped shirt against door), Martin Hall (Merge), Sasha Bell (Ladybug Transistor), Marisa Anne Brickman (‘Sup magazine, turning to camera), Mike Wolf (Flying Nun U.S., wearing flashlight T-shirt).

Lambchop’s Kurt Wagner and Mark Nevers with NPR’s Renée Montagne, Los Angeles, 2000.

Members of Lambchop dash through the rain to Mac’s house during the Merge 10th anniversary festivities.

Merge’s 10th anniversary cake.

Stephin Merritt on tour, 1998.