2000 to 2009

Superchunk’s last full-length album – that’s “last” as in “most recent,” not “final” – was provocatively titled, at least to some observers, Here’s to Shutting Up. The implication being that the band, after a dozen years and as many records, was trying to say with a wink that it had recorded its swan song. Here’s to Shutting Up may well end up being the last Superchunk full-length, but it wasn’t planned that way. The band had settled into a slower-paced rhythm of a record every other year. Mac and Laura obviously had plenty to occupy them during the downtime, and Wurster had started a comedy duo with Scharpling based on characters Wurster would play while calling in to Scharpling’s WFMU radio show.

They wrote Shutting Up in the fall of 2000 and winter of 2001 at Wilbur’s house, a remote outpost deep in the woods west of Chapel Hill that he shared with Brian Paulson and George Nicholas, who was Merge’s attorney before McPherson. It was known as the Hurlyburly House, after the play and movie by David Rabe, owing to many a late drunken night passed there. They spent three-hour sessions there, three days a week, building songs from the ground up. For the first time, they employed acoustic guitars and keyboards in the writing process, and planned an even more drastic step away from the “classic” Superchunk sound than Indoor Living and Come Pick Me Up.

Mac I wanted to make a record that blew out people’s expectations of Superchunk. One thing, however, is that people don’t especially want their expectations blown.

They systematically wrote and recorded snippets of songs and riffs to be later combined into full compositions, coming up with about thirty in total, most of which Wilbur concocted a nonsensical name for – “Something About Marvin,” “Frank’s Bath,” “Ford’s Lobsters,” etc.

They recorded Shutting Up in March 2001 with Brian Paulson, who was working with Superchunk again for the first time since Foolish, at Zero Return, an emptied-out warehouse with a control room consisting of two shipping containers fused together and set up on cinderblocks. It was built by the members of Man or AstroMan? in Cabbagetown, a transitional neighborhood in Atlanta, and it had rooms to sleep in, so the band rarely left the confines of the studio and started slipping into an all-night schedule that kept them recording until 4 a.m. Breakfast was carryout from the Long John Silver’s down the street.

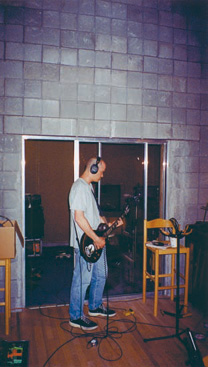

Recording Here’s to Shutting Up in Atlanta, March 2001. Clockwise from top left: Exterior of Zero Return Studios; Mac; Brian Paulson; Wilbur.

Shutting Up did indeed blow expectations. The record’s defining moment was the “who-put-peanut-butter-in-my-indie-rock” shock of hearing the whine of a pedal-steel guitar on a Superchunk album in “Phone Sex” (“I like to think that our invite for Austin City Limits got lost in the mail,” Wurster would later write). While it had its rockers – “Rainy Streets,” “Art Class,” and “Out on the Wing” – it was for the most part a layered, lazy, acoustic-driven record, and featured Superchunk’s longest-ever song, “What Do You Look Forward To?” which weighed in at more than seven-and-a-half minutes. It was a tough record to make.

Mac Doing anything new and different with Superchunk is like pulling teeth, and sometimes it shows. But sometimes it’s great. We were using more effects, loops, and delays and stuff. But it’s hard for a band that has done things one way for twelve years to start doing things differently.

Here’s to Shutting Up was released one week after the September 11 attacks. Superchunk was scheduled to play the Merge CMJ showcase at the Bowery Ballroom in lower Manhattan on September 15, after which they had a worldwide tour of Europe, Japan, and the states booked. It was the worst possible time to mount a tour.

Mac We sort of didn’t know what to do. We didn’t know if there was going to be a show, or if CMJ would be cancelled.

Jon Wurster Mac wanted to go. I didn’t really want to. It was just, “Oh my god.” Jim didn’t want to go, I don’t think Laura wanted to go. It just didn’t seem appropriate. I know there’s the whole thing about “rock’n’roll can get us through,” but I wasn’t feeling that at all.

Laura I could not believe Mac wanted to go there. I guess it’s part of his personality: He wants to be where things are happening.

Phil Morrison Mac and our friend Dave Doernberg and I drove up to New York from North Carolina on September 13. We’d all been at our friend Joe Ventura’s wedding the weekend before.

Mac The Clean was scheduled to play that same night as Superchunk. Those poor guys had arrived from New Zealand on the 10th to wake up to that on the 11th. They wanted to leave the U.S. immediately, but of course they couldn’t.

Bob Lawton We didn’t even know if the Bowery Ballroom was going to be open on Saturday night. We didn’t find out until the end of the day on Friday that they were actually going to have electricity. It was supposed to be a Merge showcase. And Mac could get there, and maybe one or two other bands.

Mac We had to construct a show from bands from other labels that had already made it to New York before 9/11. So we had Ladybug Transistor for Merge, and the Faint and another Saddle Creek band because their showcase was cancelled, and we got Laura Cantrell because she lived in New York, and the Clean. And I played solo.

Bob Lawton We just cobbled this thing together and made it a benefit, and gave all the money to the local fire station closest to the Bowery Ballroom. It was cathartic to see bands coming together and playing. Take a bad thing and try to make it good. We’re rocking and we’re going to go on, just like everything else is going to go on, eventually.

Mac It was a really emotional night. People were in tears during Laura Cantrell’s set, and the Clean did a really powerful version of this old song of theirs called “No More Violence.” The air still smelled burnt. I was really glad we made it happen in a way that seemed to make anyone who came feel a bit better. Or at least gave some people a place to be around other people.

A trip to the movies, the celluloid cave, offers escape; theater provides the ritual of repetition. But live music at its best absorbs the listener in every next step. The most successful artists at the Bowery Ballroom concentrated on tangibles, not transcendence. In a time of isolation, their art connected people modestly, at just the right scale for spinning heads to grasp.

—New York Times review of the CMJ show, September 2001.

Jon Wurster So then we did this tour, and it was so tough. We wanted to just hit everything – bam bam bam. So we flew from Raleigh to Tokyo. And then we were going from Japan to Europe, but it was cheaper to fly back to Raleigh and then to Europe. So we went home for one night and then we flew to Europe the next day.

The Archers of Loaf’s Matt Gentling came along for the Japan leg of the tour as a guitar tech.

Matt Gentling We landed, and Jim drove me in the van from the airport to my truck. And he was going to go home, do some laundry, catch a couple hours of sleep, and then the next morning they were going to get up and go to Europe. Like, immediately. I could see how tired they were. There was just this overall pall of fatigue.

Jim Wilbur It was a bad time to try and promote a rock record. Just took the wind right out of everybody’s sails. That tour was brutal.

Jon Wurster And because of what was going on in the world, nobody was coming out to shows. So we did Europe, and that sucked, and we played in England and that sucked. Our final show was in Dublin. No money. Promoter didn’t have the money, because our agent had done some deal with him where he didn’t have to pay us. It was so fucked up.

Jason Ward That tour was remarkable for the incredibly poor attendance in all places save for London, Paris, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam. Everywhere else it was just insane – an 800-person room with, like, 40 people in it.

Laura Everything went wrong. The van kept breaking down, no one was coming out, and those that did seemed to be in a daze.

Jon Wurster We flew back to the states, had four days off, and then toured the entire U.S. It was tough. Turnouts were not great; nobody was really going out. The last show of the tour was in D.C. with Aereogramme and Rilo Kiley. I consider that the final real Superchunk show, in a way. That was our final show as a full-time touring concern slash real band. I think at that point, I had made my mind up that this is not going to be my full-time thing anymore. And I think Laura felt that way too. When we were rehearsing for that tour, she was just not really in a great place. I remember just hugging her, at one point, and she was just not feeling good about the band. She wasn’t sure if she wanted to do it anymore. When we got home, Lawton e-mailed about some more dates for maybe March or February or something. I just looked at these dates, and my stomach sort of started to churn. I just didn’t want to do it. Same places. Same songs. It just wasn’t interesting anymore. It wasn’t fun. I mean, it was fun to be around the guys, because I still had fun with them. But it felt like a treadmill.

Phil Morrison There was a point where Jon started thinking about just removing from his life the things that caused him anxiety. It was kind of a conscious choice. You get to a certain age, and you think, “Wait: Do I even still want this? Or has it just become habit?”

Bob Lawton I remember just being on pins and needles. Like, “Whoa.” It was huge.

Jason Ward We were all sitting there going, “Maybe this era is kind of over.” Especially in terms of the expense of touring.

Matt Gentling Stuff was going wrong. And another thing is, Merge had some great bands coming up like Arcade Fire and Spoon, and those guys were starting to make them money, on one hand, so they didn’t have to tour. You know, I could tell they were tired and kind of burned out on what they were doing.

Superchunk on tour in Japan, 2001. Clockwise from top left: Wilbur; Mac and Laura; Wilbur, Japanese soundman Hiro Kanazawa, and Mac; Wurster.

Jim Wilbur It was just kind of like a depression. Jon was really upset. And then we did a tour with the Get Up Kids.

The Get Up Kids were early standard-bearers for the emo scene (as well as huge Superchunk fans – they named their debut record, Four Minute Mile, after a line in “Yeah, It’s Beautiful Here Too”). Their 1999 sophomore record Something to Write Home About helped put Vagrant Records on the map as a label that knew what fourteen-year-old kids wanted to hear. In 2001, Interscope bought a minority share in Vagrant, in part on the strength of the Get Up Kids’ sales. Scott Litt, who had worked with R.E.M. and Nirvana, produced their 2002 record On a Wire.

Robbie Pope We put together a huge list of bands that we wanted to take out, and we all were kind of like brainstorming and somebody threw out Superchunk. At that point, it didn’t seem like they were up to a whole lot. When I was in high school, I listened to Superchunk all of the time. And so did all of my bandmates. Foolish was a big record for all of us. So we were like, fuck it, let’s have our booking agent ask them, and see what happens. It was like kind of like a dream come true, because your favorite band from high school is actually opening up for you. Which is also a little odd.

Bob Lawton It was almost as if they were afraid to ask. I didn’t know what the Get Up Kids’ crowd was, per se. I just knew they were playing these big gigs, and that the Superchunk thing was a little on the wane. It was a time when you were thought of negatively if you’ve just been around forever. Everyone wants the new thing. And this was a lot of young people who wouldn’t normally go see Superchunk.

Mac Here’s to Shutting Up was a really up and down tour, and we really didn’t plan on doing much more touring for that record. But they weren’t treating us like an opening band. They were paying us well, and we’d be able to play a normal-length set. So why not try to play for a completely different group of people than we would normally play for? We had a great time. We all love opening for other bands. You get there last, because the main band’s soundchecking, so you can show up late, soundcheck, play early, and then just hang out.

Robbie Pope It was kind of awkward at first. The tour started in Florida somewhere, and we had soundchecked, and we were all kind of nervously excited because Super-chunk is going to show up and play. So they show up, and we do the “Hey, we’re going on tour together, yay!” thing. And right before Superchunk goes on stage, we’re all kind of standing there, chatting, drinking a beer, saying, “Have a good show.” And as Jim walks by to go on stage, he just turns and says, “Watch and learn, boys.” It was hilarious.

Mac The Get Up Kids were super professional. They were on a bus, we were in a van. They had the light show, they had a whole thing. I don’t think any of us felt like, “I wish we had done that,” or “I wish we were doing that.” To me it was more, “I’m glad we’re doing what we’re doing.”

Jim Wilbur That was a demoralizing tour, to a degree. Nobody cared about us. But the idea was that we’d be putting ourselves in front of a different audience on purpose.

Laura I would look down from the stage and see all these kids in the front row who had clearly rushed in to grab a spot as close as possible to the Get Up Kids, and they would make a show of looking as bored as possible during our set. Some would even have their head down on the barrier in front of the stage, trying to catch a nap before their favorite band came on. I found it hard to muster much enthusiasm most nights.

Mac Certainly there were nights when you feel like nobody cares. Like they’re all thirteen years old and literally just like waiting for the Get Up Kids. But that’s cool. I thought it was really fun. After we’d play, we’d go hang out at their T-shirt table, and we were talking to kids who were like twelve, thirteen, fourteen, and were with their moms and dads. It was so funny.

Robbie Pope Everybody in the Get Up Kids had a girl-in-the-band crush on Laura when we were growing up. And now Laura is on tour with us, and at one point we’re all drinking and hanging out. And Laura was chatting just like one of the guys, and talking about some toe fungus she had. And I remember thinking, if you had told me when I was sixteen that one day I would be sitting with Laura Ballance talking about her toe fungus!

Laura I never had a toe fungus. I was probably talking about my bunions. Robbie probably still thinks that bunions are a form of toe fungus!

The Get Up Kids shows were mostly sold out, and most of them were in venues larger than Superchunk usually played. But the audiences were largely uninterested in Superchunk, and any hopes of kindling a Superchunk revival among a younger audience didn’t pan out. Shutting Up sold 17,000 copies, their worst-selling record since their self-titled debut.

Jim Wilbur I wasn’t ready to give up. But everyone was tired and kind of demoralized. And Laura got married. And Mac had a baby. I was like, let’s not work on a new record right away. Let’s just sit back.

Jon Wurster We had a meeting at Laura’s place. And at that point I was ready for it to be over, so I could move on. And Mac said, “That’s fine if you don’t want to do it anymore. But let’s not break up. Because bands that break up don’t keep selling catalog records.” On the one hand, I understood that. And on the other hand I almost wanted some finality to it.

Jim Wilbur I was upset. Mac and I both didn’t want to stop. And Jon was like, “I want to say that I never want to play some of these songs again. I want to say that.” I said, “It’s a trick in your mind that says that you know more now than you’re going to know in two years. And for you to say that means you’re sort of desperate. Why don’t we just see how things lie and see how we feel?” And then Jon was like, “Could we just say that we’ll only do something if we’re all a hundred percent into it?” And I was like, “Of course. Nobody’s going to force you to do something you don’t want to do. But that doesn’t mean you have to underline it quite so hard.”

Mac Bands that break up always get back together, and I didn’t want to get on the reunion train in a year. Mainly I just thought, “Why not just take a break?” We also had a show already booked, a benefit for Alejandro Escovedo at a club in Raleigh. And I didn’t want Superchunk’s last show ever to be at some crappy nightclub in Raleigh.

Jon Wurster In retrospect, it was a smart thing to do. Because we play a couple times a year, and it’s not like every time we play again, it’s like, “They’re getting back together again,” you know? Because technically we didn’t break up. And we’ve managed to record a song a year probably. So it all kind of worked out. And I’m glad that Mac sort of pushed for it to not be completely over.

Superchunk went on one more tour after the Get Up Kids, a brief East Coast swing in 2003 to support the release of Cup of Sand, their third collection of B-sides and rarities. They’ve released two limited-edition live CDs as part of the Clambake Series (“clam” is musicianspeak for a mistake); one of acoustic record-store shows and one of an original soundtrack they performed live for a screening of the Japanese silent film A Page of Madness during the San Francisco International Film Festival in 2002. They’ve gone into the studio to contribute tracks to compilation CDs here and there, and released one 7-inch-only single of “Misfits and Mistakes,” for the soundtrack to the Aqua Teen Hunger Force movie. In 2009, they released Leaves in the Gutter, a five-song EP. Live, they’ve reconvened for various benefits – a show in Chicago to raise funds for the Ulman Cancer Fund for Young Adults in memory of fan Sean Silver; a couple of shows in North Carolina to boost voter registration for Barack Obama – and other special occasions, like The Daily Show’s 10th anniversary party in 2006.

Of the latter show, the Village Voice wrote:

They’re still around, and they’re still closing shows with the first single they ever released, and somehow that’s not really the least bit depressing. Their charged-up fuzzcore felt deliriously warm and comforting even when it was new, and they still take a visible childlike glee in guitar windmills and peals of feedback… I hated seeing the Circle Jerks last month; it seemed like such a cynical ploy for these middle-aged guys to keep pounding out the same angry tantrums they wrote when they were teenagers. But Superchunk wasn’t anything like that, maybe because their songs deal with emotions and ideas [that] could be considered adult. I didn’t really get “Slack Motherfucker” when I was 13; I’d never had to work a shit job. I get it now.

Jim Wilbur We were doing well right up to when we stopped. And we do well when we come out of retirement.

Jon Wurster I think to this day, Superchunk will always be remembered more for how we did it than what we did. At this point, Superchunk is the band that’s led by the two people that put out the Arcade Fire records. And that’s fine. It’s better than nothing.

Dan Bejar and Fisher Rose of Destroyer backstage at South By Southwest in Austin, Texas, 2008.

Conor Oberst and M. Ward.

David Kilgour.

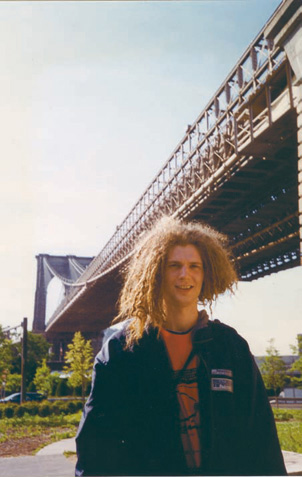

Matt Elliott of the Third Eye Foundation at the Brooklyn Bridge, 1997.

Gonson and Davol at the 69 Love Songs record release party in New York, 1999.

The Magnetic Fields’ Sam Davol, Claudia Gonson, and Stephin Merritt on tour in Europe, 2001.

The Magnetic Fields at the Cat’s Cradle during Merge’s 10th anniversary fest.

Dudley Klute, Merritt, and LD Beghtol,1999.

Misspelled marquee, London, November 2000.

Merge Christmas card, 1999.

Misspelled dressing room sign.

The Rock*a*Teens.

Video shoot for “Art Class” from Here’s to Shutting Up, directed by Norwood Cheek (foreground), 2001.

Wurster singing karaoke in Tokyo, 2001.

Backstage at the Paradiso, Amsterdam, 1998.

Mac as Glenn Danzig, Halloween 1998.

At the Paradiso.

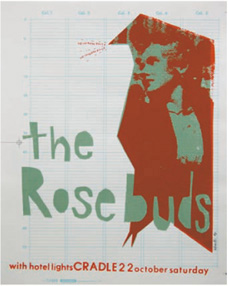

Poster by Ron Liberti, 2008.

The Rosebuds.

Merge coaster.

Poster by Ron Liberti, 2005.

Wurster on tour.

The “Music Tapes House Capsule,” featured on the pop-up album art for Music Tapes for Clouds and Tornadoes.