Transport: Chartres and Berchères-les-Pierres, June 1940

IN THE JUNE 3 BOMBING RAIDS, FIVE WAVES OF GERMAN PLANES OF twenty-five or more each attacked Paris around 1:00 p.m. and again just before 2:00 p.m., part of Operation Paula, Germany’s plan to destroy the French Air Force, the first against any belligerent capital and the first to hit Chartres since World War I. Antiaircraft fire blotched the sky with gusts of white smoke, which, together with attacking French fighters, forced the German bomber crews to remain above thirty thousand feet, preventing them from accurately hitting military targets. Over one thousand bombs fell in the area, eighty-three in western Paris and the balance in a circle around the city, including the Citroën automobile factory. Planes attacked the airfield of Issy-les-Moulineaux, between Paris and Versailles. Other bombs fell at Le Bourget Field, east of Saint-Denis, on the city’s northern edge, and other airfields as far southwest as Chartres, where at least twenty bombs fell on that city’s west edge. From the highest point in Paris, atop Montmartre on the north riverbank of the Seine, observers could see flames and smoke from bombs bursting at points over a five-mile area with columns of smoke from five fires. The all clear was given at 2:18 p.m.

Two days later, on June 5, a second bombing raid on the Chartres airfield killed eight and injured many more. In his role of prefect of Eureet-Loire, Jean Moulin visited the wounded in the hospital. The raids were worse twenty-one miles north in Dreux, with over one hundred dead and much of the town center destroyed, including most hospitals. In the days following, journalists reported that 254 persons had been killed in that day’s bombardments. Nearly two hundred were civilians. In the operation, German formations had attacked twenty-eight railways and marshaling yards, but all of that damage inflicted was light. None were out of action for more than twenty-four hours.

Even while the June 5 raid was under way, Jean Moulin, Jean Chadel, and their prefectural staff were probably working with Roger Grand to arrange for Chartres volunteers to come back to help remove the windows from the crypt for transport to a safe haven. Moulin had much to do, first consoling wounded in the hospital and then mobilizing teams of volunteers and soldiers, tools, and equipment. Some who had helped with the window removal during the eight days in August and September 1939 probably would come back to help, but the situation in Chartres had deteriorated since then. The climate of fear caused by the bombings of June 3 and 5 and the stresses of a threatened invasion—including displacement of large numbers of people from the east and from Paris through Chartres and surrounding areas—made it difficult for civic leaders to find Chartres residents willing to volunteer for the tasks that would require them to be away from their families for a full day and possibly into the night. It would be a rush of collective multicultural sweat, blisters, aching arms and feet, and diesel exhaust—at the cathedral, at the railhead at Berchères-les-Pierres, and along the train route south.

Captain Lucien Prieur’s military group would have been inundated, and Ernest Herpe’s Fine Arts Administration could do only so much, working through private contractors, given the wholesale disruption of Paris life.

On the morning of June 8, a Saturday, Jean Moulin would have been disheartened that the weather was fair. He would have been hoping for rain and fog—or, at the least, overcast skies—to degrade visibility from the air, to shroud the cathedral and the streets and roads south of town from the eyes of German pilots who were continuing to terrorize Paris and towns south and west to force the French to surrender.

To accomplish the day’s enormous workload, Moulin and his team must have known they would need 115–140 men. So, probably on Moulin’s instruction, Jean Chadel’s prefectural staff would have solicited in the train station and refugee shelters for men seeking work to come to the cathedral on Saturday, and maybe Sunday, likely for two shifts of ten to twelve hours of work, one shift to start early in the morning, the other in midafternoon. Ironically, they could be turning to foreigners and displaced persons for a significant part of the manpower needed to save the windows, a French historic and artistic treasure.

Moulin would have been lucky to have managed even a few hours of sleep in the predawn hours of that day, having had to work well beyond dark—even on those long days of June, night after night, especially since the bombing—his head probably swimming as he arrived at the cathedral. The tidal wave of emergencies swirling around him would have been enough to turn anyone’s mind to a blur: he would have shuffled through crowded prefecture hallways to Chadel’s and other staffers’ desks, reaching truckers and drivers by telegram and phone. He would have taken calls and meetings in his office with people begging for help, exchanged messages with Lucien Prieur to press railroad managers to summon to the cathedral the few soldiers who’d remained in town, to haul crates and serve as guards on the train carrying the windows to Fongrenon. He would have ordered soldiers to guard the trains along the journey and the trucks at either end and implored Roger Grand to line up more volunteers of his citizen contingent to come back to the cathedral to haul the crates onto trucks and to provide food and drink for the workers.

But Jean Moulin had stuck with it. He was no ordinary man. He was determined to get the windows out before the invasion could overrun Chartres.

Moulin walked up the hill from his rooms at the prefect’s residence. The smell of cordite lingered in the air from Wednesday’s bombs, a smell Moulin knew from his nearly two years of work for Air Minister Pierre Cot. Moulin’s official residence lay in the shadow of the cathedral, a residence he called “comfortable enough” but “ostentatious and in bad taste.” His own Citroën would have just been an impediment at the cathedral, with the fleet of more than fifteen lorries soon to arrive. Even a small grouping of trucks in those small spaces would cause a tangle, but the much larger conglomeration of trucks summoned to the cathedral for the busy day ahead would create a dangerous confluence, requiring planning and control amid the mass of men and machines on the site that day and into the night.

The earliest sunlight reflected off the sun-bleached masonry and white stucco of the buildings and limestone of the cathedral’s towers and sculptures and illuminated the weathered pale-green patina of the great roofs of the cathedral and the rust-red roofs of the surrounding buildings. Early rising Chartres residents emerged from their homes to begin the day, but the sounds of hammers and vehicle engines were already fracturing the tranquil morning of the town. Dogs barked, buckets clattered, milk bottles rattled, and brooms swept as the townspeople began their chores amid the sounds of work at the cathedral.

Moulin came within a couple of blocks of the cathedral, and he could hear sounds of activity: carpenters called out measurements, saws sliced lumber, hammers struck nails, and boards slapped and clanked as workers hauled lumber off trucks. Michael Mastorakis had assigned the earliest task to the carpenters. They were to build a set of three wooden ramps to enable men to push handcarts bearing the window crates out through the cathedral’s west door and down its steps onto the courtyard for loading onto waiting trucks. Joiners had been hard at work since before dawn among piles of tools and supplies—wheelbarrows, sawhorses, tool belts and -boxes, water cans, nail buckets, and piles of boards scattered around the front of the cathedral and on the broad floor of the nave inside the west entrance.

The day’s work would be to haul the nearly one thousand wooden crates out of the cathedral’s basement crypt into the courtyard to be loaded onto trucks. From the crypt, a vaulted hallway led through an arched passageway and up a five-foot-wide set of more than a dozen stone steps, leading through an iron gate to another set of eight stone steps up to the main floor of the cathedral, one hundred feet from its west entrance. At the top of those steps, teams would place each crate onto a handcart to be rolled to the entrance. There, they would have to push it over the three new ramps. The first ramp ran over the entrance door’s threshold into the portal’s shroud. The second ramp ran down the cathedral’s half dozen front steps beneath the temporary shroud or rampart toward the outside entrance. The third ramp ran over the threshold of the shroud’s outer door to the courtyard. From there, each cart would be rolled to a waiting truck.

The second task facing Moulin and the military and civilian teams would have been to organize those of the workmen they’d instructed to arrive early. They divided them into teams and instructed them on what to do and how to do it—all in time for the arrival of the first couple of trucks whose drivers they’d told to arrive before 8:30 a.m. The remaining drivers would have been told to schedule their arrivals later—in intervals throughout the day.

Moulin and Mastorakis, along with Captain Prieur, likely had estimated that the work would take all day and continue into the night. They planned for the fifteen trucks to make two trips from the cathedral to the rail spur. Risks of additional German attacks were growing. They had to pack the crates in and move as quickly as possible to come back to the second load. Traveling during daylight, they would have to somehow minimize chances of being spotted from the air. Later, the waxing crescent moon on June 8 would provide only 7 percent of full moonlight and furnish a cover of darkness, but only if lights were avoided or modified under blackout protocol.

The loading and transporting would have to be done quickly. Moulin likely knew that the situation in France—from the view of leaders in Paris—was deteriorating fast. News was already spreading that French prime minister Paul Reynaud had dismissed his supreme military commander, Maurice Gamelin, and replaced him with Maxime Weygand, and Reynaud had named Philippe Pétain, hero of World War I, as deputy prime minister. As would become apparent, neither Weygand nor Pétain felt the Germans could be defeated. They began looking for a way out of the war.

By the time Moulin and the others had gathered at the cathedral on June 8, the security situation had become perilous. Trains filled with refugees were departing Paris’s Gare d’Austerlitz train station with no announced destination. When the prefectural assistants arrived at the cathedral from Jean Chadel’s office by midmorning to meet Moulin, they would have told Moulin that calls were coming in from Paris: German shelling could be heard in the Paris suburbs.

That morning, Moulin, Mastorakis, and Prieur would have been faced with a crowd of men lined up outside the cathedral—likely an amalgamation of Czechs, Poles, Belgians, and French from Alsace-Lorraine—eager to start work, yearning for pay of any kind. Many would have spoken no French, so the matter of issuing orders would have been somewhat complicated, with those who could speak some French and another language doubling as translators. Michael Mastorakis, Louis Linzeler, and Roger Grand probably got the crews working right away. There was plenty to be done.

Mastorakis led the first five-man crew of workers down into the crypt. There, the windows rested in more than one thousand fully loaded crates, stacked on end like huge slices of bread in loaves. The smell of freshly cut pine saturated the damp, dark air of the crypt. Each pine crate rested on its narrow edge, the glass carefully packed tight inside. The two rows consisting of crates resting flat side to flat side, along the long walls under the sixteen-foot barrel vaults, looked like two lengthy rows of giant volumes resting in two gigantic bookcases facing each other; these newly assembled volumes, however, now contained not pages with words but precious panes of nine-hundred-year-old glass, displaying variegated, tinted graphic stories, each sealed in a wooden receptacle for safekeeping to ward off war damage. For every few crates, workmen had hammered slats of wood in place to secure against falling if crates were to be removed or jarred.

The gallery’s walls beneath its barrel vaults, some sixteen feet tall, were mostly covered with frescos starting at shoulder height. Each team of five men, cautioned to avoid scraping the walls, began by hauling a crate by hand from its position in the row of crates across the smooth-worn old herringbone-brick floor. Four of the men in each team, working in pairs, two men on each side of the crate, flung ropes over their shoulders, the partner of each man on the other side of the crate doing the same, draping the rope over his shoulder and around his back and then wrapping it around his wrist to increase traction for lifting and control. The men then lifted the crate and hauled it along the gallery toward the hall doorway. The fifth man in the team stood by for relief, in case anyone faltered or to guard against obstacles. The team edged down the hallway, step by careful step, and then up the first flight of smooth stone stairs, their surface polished by centuries of shoes of priests and pilgrims, and subsequently through the crypt’s iron gate and up the second flight of steps to the cathedral’s first floor, sounds reverberating throughout the open expanse far above them up to the nave’s vaulted ceiling.

Workmen called out questions, and supervisors answered with orders and encouragement and prodded them to keep moving, with wheels of carts creaking, coils of ropes being cut to carrying length, the smooth surface of the amber-colored stone floor reflecting dust kicked up and fibers from ropes floating in the air, with wisps of cigarette smoke illuminated by thin shafts of natural light peering through cracks between the temporary vitrex window coverings, and everything infused with smells of incense, sweat, drying pine boards, cork powder, and grease under the high vaulted ceilings of the nave.

At the top of the stairs, the team placed the crate onto a waiting handcart, which they rolled toward the front door and then guided up and over each of the three newly constructed ramps, down to the level of the courtyard, finally rolling the cart across the rough cobblestones of the courtyard to a waiting truck.

At least half of the thousand crates would have to be loaded and hauled out in a first convoy of trucks by midafternoon in order to arrive six miles south at a railhead at Berchères-les-Pierres, and from there the crates would have to be unloaded and transferred to the first train cars. After that, the trucks would have to return to the cathedral for the second load of crates and return to the railhead and unload for the trains to depart during the night.

The first couple of trucks arrived at the cathedral early and took their positions side by side in front of the west entrance shroud. Each driver then climbed into the back of his truck to meet a pair of additional workers and prepare their ropes to receive the first crate. As the first cart with its crate arrived, two men waited in the cargo hold of the truck with the driver. The men used ropes to pull the crates on to the trucks.

At any given time, several handcarts were making their way from the doorway of the shroud out to the waiting trucks. In all, the project would have required as many as 115–140 men.

By midmorning, Michael Mastorakis had probably made enough progress with Louis Linzeler—assembling teams of workmen and arranging for their supervision—to attend to other issues. The effects of the June 3 and June 5 bombings on the cathedral were a concern. Mastorakis and Linzeler, with binoculars in hand, at some time would have walked slowly along the interior and perimeter of the cathedral, peering up at its walls, inspecting for any damage that may have been sustained from impact of the exploding bombs affecting the temporary vitrex window coverings, or in the structure of the cathedral. Because the cathedral was sealed with temporary window coverings, the air pressure and vacuum force resulting from bomb explosions were a concern. Mastorakis and Linzeler may again have considered prophylactically removing some of the window coverings to permit free passage of shock waves to avoid damage to preserve the remaining temporary coverings and the supporting armatures.

Soon it was noon, and Mastorakis called for a break for the teams of porters. Jean Moulin, his staff, and the curate worked with Roger Grand’s volunteers and with nuns and priests from the seminary to arrange for townsfolk to supply food and drink and servers to distribute to the workers. Wash buckets filled with water provided cooling wet relief, cotton rags providing a sense of order. Double French doorways of the bishop’s palace across the courtyard were flung open to reveal long tables staffed by smiling matrons and daughters, perhaps even a few girls flirting with the workers. Water and wine poured from jugs into cups, soup filled bowls, and stacks of baguettes and cheese and sandwiches of coarse bread and sausage and mustard quickly dwindled and were replaced with new stacks. Reused cans as serving vessels were heaped with pickles and slaw, celery and carrots, the cans rattling as they emptied into cups carried away by the hungry workers. Bowls of red and yellow fruit, sweet green peppers and peas in pods, resembled dessert. Simmering coffee, with its mist rising, was poured into cups, its aroma spreading across the workers, who were eating, drinking, and probably resting on chairs in the shade of the courtyard between shifts, some perhaps lying in the shade along the walls of the courtyard to catch a quick nap before resuming work.

The men deserved this break. This great effort of men working as a team in unison—like the rituals that had been repeated for centuries at the cathedral, through wars and disputes and campaigns of terror and fires and storms—was what it took to watch over the great cathedral and its art. The dedication and sweat of men—generations of men—through the centuries. And these men were doing their part. Some had grown up in Chartres, attending the cathedral’s weekly events for years. Some were occasional visitors. Some were simply accidental visitors, looking for a few francs to feed their families while looking for other work, having left their homes in the east as the German invaders moved in, thankful to have their wives and children alive and nearby, at least safe for the day, with the prospect of a roof over their heads and something to eat until tomorrow’s search for more.

By early afternoon, the time was approaching for the first convoy of trucks to be heading down the hill and out of the city, south to Berchères-les-Pierres. That tiny village wasn’t much more than an intersection of two dirt roads a few hundred yards off a paved one. A few dozen scattered buildings surrounded the intersection, including barns for storage of wheat, a gateless-train crossing, and a small pale-brown-stuccoed train station of two stories plus attic, with a three-door waiting room on the first floor facing the track, with several brick-lined windows on the second floor, each framed by a pair of green wooden shutters. The station’s attic could quarter a seasonal extra stationmaster. A single rail track ran past the station, toward Chartres on the north and Courville-Sur-Eure on the west. Twenty yards south of the station, the dirt road, without crossing gate, passed over the track next to a one-room railroad switch hut. Nearby, along the track, a spur a few hundred yards long joined the track where boxcars could be parked to be filled with seasonal wheat to be hauled to markets. A sea of fields of freshly planted green wheat stalks surrounded the village on all sides. Distant explosions could be heard to the east.

By midafternoon, a small black steam-switching locomotive came to a halt at Berchères-les-Pierres, pulling two boxcars with wood siding painted a fading brown. The switchman jumped off and stood next to the SNCF letters painted in red on the side panel of locomotive’s tank. The engineer looked out from under the visor of his flat-topped engineer’s uniform cap, as the engine’s steam slowly hissed, a dog barking nearby. He called out to the switchman, asking whether there was anyone in the station. The switchman shrugged and walked over to the station, knocked on the locked doors, and called for anyone inside. There was no answer—no one inside the station or anywhere nearby.

The waiting engineer looked through the window of his locomotive cab behind its black steam-simmering engine and saw thin streaks of smoke rising in the sky far to the north and east. Deep-toned, faint thumps of artillery and muted bomb explosions recoiled far off in the distance. The switchman, finding no one, looked around, puzzled.

The engineer asked where everybody was and whether this was the right place. He’d been told to drop the boxcars and return the engine right away to the yards where it was needed for repair work and repositioning cars and other equipment.

He called out to the returning switchman, “15:00 latest, they said. If no one comes in twenty minutes, we’ll spur the cars and leave them unlocked.”

The switchman shrugged in agreement.

Within minutes, the sound of an approaching car caught their attention. A black Renault sedan pulled off the main road in the distance and headed toward them, trailed by its approaching dust cloud along the dirt road. A young man jumped out, introducing himself as an assistant to Jean Chadel, confirming that, yes, this was the right place and that the first trucks would be arriving within the hour and that preparations for their arrival would be needed. The engineer answered that the switchman could stay for a short while if someone could drive him back to the marshaling yard at Chartres before the afternoon was out, but the engineer had to get the locomotive back right away; the engine was needed there. He or another engineer would return to Berchères-les-Pierres later with two more empty freight cars.

Jean Chadel’s assistant directed him first to position the cars as close to the road as possible, to minimize the distance crates would have to be hauled, but the engineer said he couldn’t do that. He couldn’t leave them on the through-track. He’d have to park them on the spur. A rough dirt road came close to the spur. They’d have to haul the crates by hand from there to the boxcars. So the assistant jumped back into the sedan to return to the cathedral for additional men.

The engineer and switchman moved the boxcars onto the spur, disconnected and unlocked them, and then left. Good luck, they said. They’d be back. The switch engine chugged off to head back to Chartres.

Back at the cathedral, the assistant told Jean Moulin that the boxcars had arrived but more men would be needed to carry the crates from the dirt road to the railcars on the spur. Vehicles would be needed to shuttle at least two dozen, and maybe three dozen, workmen to the train siding.

A half dozen of the trucks had been loaded with crates. As the loading of the others continued, Michael Mastorakis directed two supervisors to round up a dozen men each and to locate vehicles right away to shuttle those men to Berchères-les-Pierres. Only one van could be located initially; Mastorakis directed its driver to take him with a dozen men while two of Moulin’s assistants left with the other dozen to gather up any cars they could find to transport them. Meanwhile, one of Lucien Prieur’s team sent men back to the Rupp District to commandeer an additional military vehicle or two. The first six trucks, loaded with crates, pulled out from the cathedral as a convoy, accompanied by two military personnel carriers (one in front, one in back), journeying down the hill and south to Berchères-les-Pierres. Several porters hopped into each truck with handcarts and dozens of ropes for hauling crates.

When the trucks arrived, the supervisor directed the first to back onto the road next to the spur as close as possible to the boxcars. The first team of five moved in with its ropes. Two helped on the truck, the others lowering the first crate to the ground, and two hopping down to help haul the crate to the rail car, the fifth in reserve in case of a trip or fall. The five-man team carried off the crate, and a team approached the truck to repeat the process for another crate; then others continued until each truck was empty. By the time the first group of trucks had been emptied and was ready to depart to return to the cathedral for more crates, another half dozen full trucks had arrived. The first trucks returned as a group, leaving the men and military vehicles at the rail-head to unload the next.

Teams of three climbed into the boxcars such that when others arrived with each crate, two climbed up into the boxcar to help haul and stack the crate on its edge in a riding position inside, the third man to tie ropes to secure the loaded crates while more were loaded. The crew returned to the truck for another crate and repeated the process. Each of the two railcars would have to carry almost 270 crates, plus two armed guards and at least one agent of the Historic Monuments Service to oversee arrangement of the crates and watch over them and to be available at the destination to ensure that the crates were properly handled and stored. Prieur’s men also loaded fire extinguishers, along with a handful of days’ provisions to sustain the guards and crew.

The second group of trucks arrived at Berchères-les-Pierres from the cathedral, and Moulin and Mastorakis arrived by car. They would have been worried that the whole project was taking longer than planned and that dangers of additional German attacks in the area were growing. By dusk, an engineer with his brakeman returned from the marshaling yards in a larger locomotive pulling a tender loaded with coal and two more empty boxcars, which it backed onto the spur and dropped off. The larger steam locomotive—an SNCF 141 R class 2-8-2, painted dark grey with red trim—could travel long distances better than the small switch engine.

The engineer told Moulin and Mastorakis that reports were coming into the rail marshaling yards: air strikes were hitting rail lines in the east and at some surrounding Paris. Moulin gave the order that the first two rail cars should be fully loaded with as many crates as possible, no matter how the crates had to be stacked, and the locomotive should depart without delay for Courville-sur-Eure, the first leg of its journey to La Tour-Blanche. Perhaps he thought it could wait at Courville-sur-Eure, or at some location farther west, for the second pair of rail cars to be brought from Berchères-les-Pierres to meet it. From there, the route would take the train to Le Mans and points south. At dusk, the locomotive pulled out from the spur and headed south, hauling the first two boxcars loaded with 539 of the crates, leaving the remaining two railcars to be loaded. Aboard were the engineer, a brakeman, two military guards, and the representative of the Fine Arts Department.

On Moulin’s order, the local stationmaster called the Chartres marshaling yard from the tiny station at Berchères-les-Pierres requesting that a second locomotive be dispatched to pick up the two remaining boxcars when loaded and haul them to La Tour-Blanche, hoping that the second train could meet up with the first train somewhere along the route to Courville-sur-Eure or a point west or south. The second convoy of trucks with the remaining 395 crates arrived at Berchères-les-Pierres. The crews worked into the evening hours, continuing to pull down the crates and haul them to the railcars to be stacked, finally finishing when the fifteenth truck of crates had been unloaded. The second train, when fully loaded, departed, but very close to the railhead it slowed to a halt. By then, continuing German disruption of the rail system by damaging tracks and equipment had blocked the routes west and south. Late in the evening, Moulin was forced to conclude that there would be no way for a locomotive to get through to Berchères-les-Pierres, pick up the remaining boxcars, and proceed to meet the other train.

But he was determined to press for a solution. He ordered the train to pull back to the railhead and the men to remove the crates from the boxcars and transfer them all back onto the trucks, which were to make the run directly all the way to La Tour-Blanche rather than back to the cathedral. But the truckers whose trucks had been hauling the crates that day were unable, for various reasons, to make such a long-distance run. So Moulin’s staff made calls for trucks to other firms in Chartres and surrounding towns as far as forty miles away—including Dreux, Nogentle-Rotrou, Charray, and Gallardon—without success. But Moulin kept calling. As the hours passed and the men loaded the trucks with the crates, the roads became increasingly unsafe for convoys. As the German invasion pressed westward, the roads became more clogged with refugees fleeing Paris and points east.

Finally, Moulin again conceded. He abandoned his plan to ship the remaining crates to La Tour-Blanche and instead ordered the trucks to head back to the cathedral. German attacks intensified during the night. Only hours after the trucks departed from the railhead at Berchères-les-Pierres with all of the remaining crates, an attack hit the station at Berchères-les-Pierres. A train carrying munitions situated near the rail cars that had contained the crates burst into flames from an explosion and destroyed all nearby railcars, including the two that had contained the crates.

For the time being, all of the windows had escaped damage, but all of the participants would have been terrified to learn that the half of the priceless collection of stained glass that had been left behind at Berchères-les-Pierres—and possibly all, if the first train had not departed when it did—could have been pulverized or burned into tens of millions of particles of blackened sand, no different from the medieval sand from which the ancient glass had been forged almost eight hundred years before.

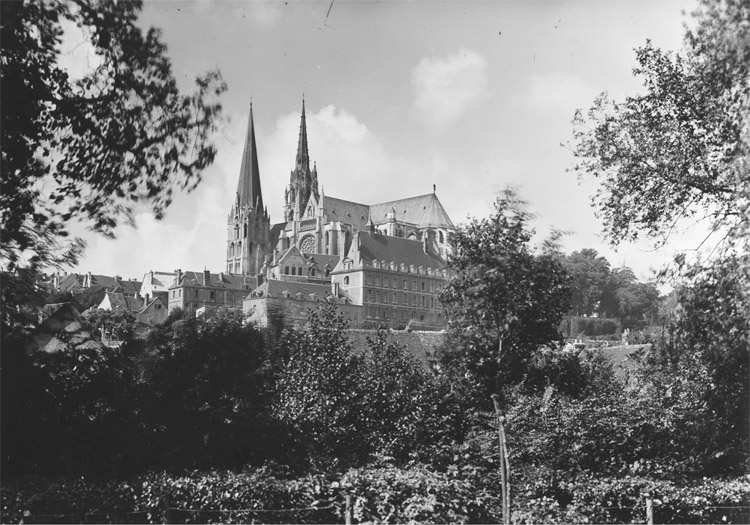

Sunlight view of north and west facades of Chartres Cathedral, from the northwest. COURTESY OF MICHAEL CLEMENT.

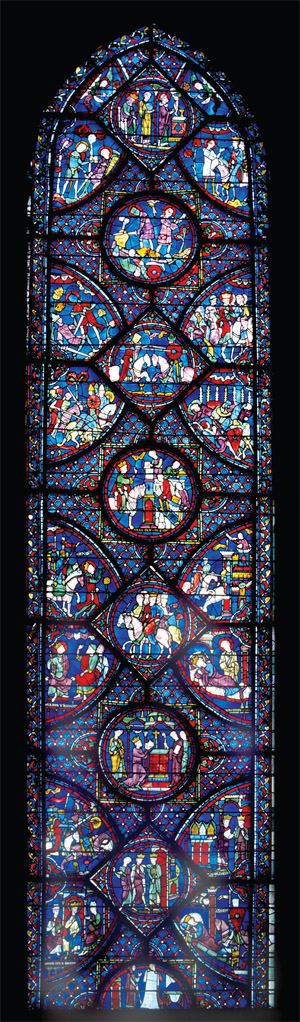

Charlemagne Window, Chartres Cathedral. COURTESY OF SONIA HALLIDAY.

Tree of Jesse Window, Chartres Cathedral. COURTESY OF SONIA HALLIDAY.

Life of the Virgin Mary Window, Chartres Cathedral. COURTESY OF SONIA HALLIDAY.

Assumption Window, Chartres Cathedral. COURTESY OF SONIA HALLIDAY.

Incarnation Window, Chartres Cathedral. COURTESY OF SONIA HALLIDAY.

West facade and towers, Chartres Cathedral in sunlight, view from the west. COURTESY OF MICHAEL CLEMENT.

Apse of Chartres Cathedral with late-afternoon sunlight, view from the choir. COURTESY OF MICHAEL CLEMENT.

Blue Virgin Window (Notre-Dame de la Belle Verrière), detail, Chartres Cathedral. COURTESY OF PATRICK COINTEPOIX.

South transept rose window and lancets, Chartres Cathedral. COURTESY OF PATRICK COINTEPOIX.

Altar and windows of a radiating chapel, Chartres Cathedral. COURTESY OF PATRICK COINTEPOIX.

Welborn B. Griffith Jr., circa 1919–1920, in cadet’s uniform, at Bryan Street High School or Texas A&M. COURTESY OF ALICE IRVING.

Welborn B. Griffth Jr., 1925, West Point yearbook, The Howitzer. COURTESY OF KEVIN COFFEY.

Welborn B. Griffith Jr., modeling infantry combat uniform, circa 1928–1929. COURTESY OF ALICE IRVING.

Griffith family, circa 1931 (Welborn Jr., lower row, left; first wife, Alice, upper row, left). COURTESY OF GARY HENDRIX.

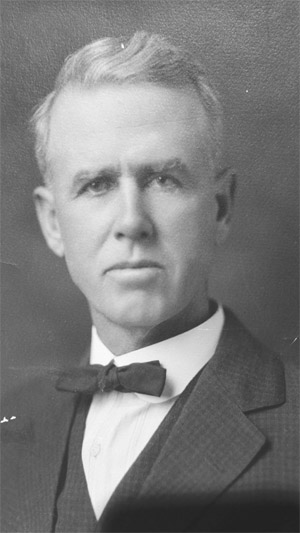

Welborn B. Griffith Sr. (L) and his wife’s brother, Harrison (Tex) Smith. COURTESY OF GARY HENDRIX.

Welborn B. Griffith Sr. COURTESY OF GARY HENDRIX.

Custom scaffolding designed by Achille Carlier, used for the front second window of the choir, during removal tests conducted March 28, 1936, at Chartres Cathedral, as shown in Carlier’s “Supplement No. 2,” page 68 of the reprint. Achille Carlier (1903–1966), architect. J. Sorbets (20th century), photographer. Preventive measures that would make it possible to rescue the stained-glass windows of Chartres Cathedral in the event of a sudden attack. “Supplement No. 2” (1935). © MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE / MÉDIATHÈQUE DE L’ARCHITECTURE ET DU PATRIMOINE, DIST. RMN-GRAND PALAIS / ART RESOURCE, NY.

Custom scaffolding designed by Achille Carlier, used for low windows in the east aisle of the north ambulatory during removal tests conducted March 28, 1936, at Chartres Cathedral, as shown in Carlier, “Supplement No. 2” (1935). © MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE / MÉDIATHÈQUE DE L’ARCHITECTURE ET DU PATRIMOINE, DIST. RMN-GRAND PALAIS / ART RESOURCE, NY.

Faucheux telescoping cranes in 1936, in the nave of Chartres Cathedral, used to reach clere-story windows and lower windows during removal tests, March 1936. COURTESY OF LES ARCHIVES DÉPARTEMENTALES D’EURE-ET-LOIR.

Jean Zay at first meeting of the council of Prime Minister Chautemps, at the Hôtel de Matignon, Paris, official residence of the prime minister, 1937. PHOTO: AGENCE MEURISSE.

Jean Moulin, 1937. PHOTO: STUDIO HARCOURT 1937.

Interior entrance to crypt of Chartres Cathedral in its present-day condition. COURTESY OF PATRICK COINTEPOIX.

Large crypt of Chartres Cathedral in its present-day condition, filled with chairs arranged for services. COURTESY OF CORINNE HALL.

View from north tower of Chartres Cathedral, showing rail yard, 2015. VICTOR A. POLLAK.

View of Fongrenon Manor (Dordogne) and the cliff line sheltering its quarry. COURTESY OF THIERRY BARITAUD.

West entrance to quarry at Fongrenon Manor (Dordogne). COURTESY OF THIERRY BARITAUD.

Large entrance room of quarry at Fongrenon Manor (Dordogne) served by its west entrance. COURTESY OF THIERRY BARITAUD.

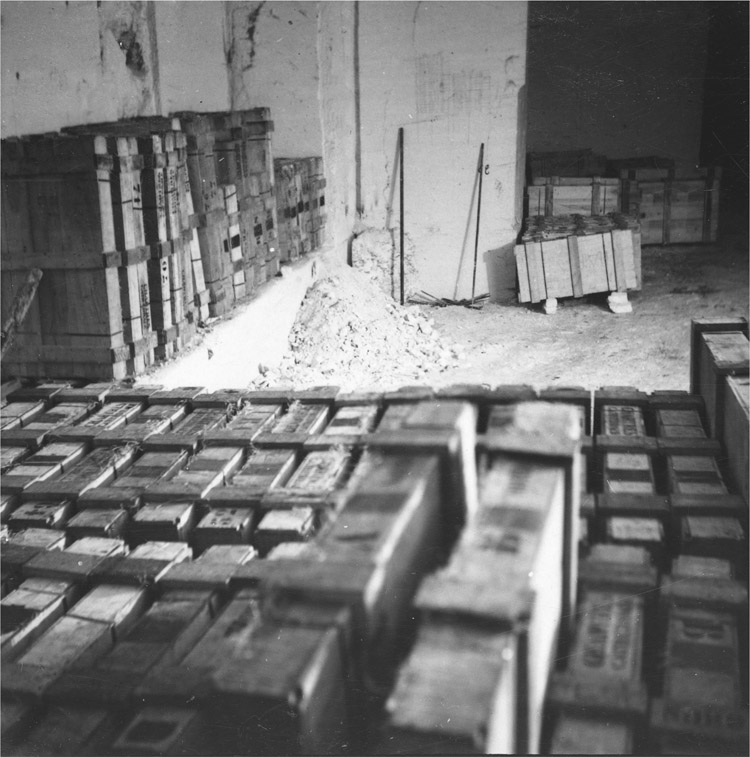

Boxes containing the stained-glass windows of Chartres Cathedral, deposited in 1939, stored in the quarries of Château de Fongrenon in the municipality of Cercles (Périgord), 1940. Positive monochrome on paper. Inv. no. 16L12226. From photographic report of J. Tourvelot of window removal and concealment in quarry. © MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE / MÉDIATHÈQUE DE L’ARCHITECTURE ET DU PATRIMOINE, DIST. RMN-GRAND PALAIS / ART RESOURCE, NY.

Welborn B. Griffith Jr., circa 1943, in street uniform and major’s overseas cap. COURTESY OF GARY HENDRIX.

View of Chartres Cathedral from the southeast, vegetation in the foreground. COURTESY OF ROBERT LAILLET AND LES ARCHIVES DÉPARTEMENTALES D’EURE-ET-LOIR (ARCHIVE OF EURE-ET-LOIR).

Welborn B. Griffith Jr. in G-3 tent, with deputy and clerk preparing orders, circa 1942–1943. COURTESY OF THOMAS N. GRIFFIN.

Eugene G. Schulz as a young GI, wearing sergeant stripes during World War II. COURTESY OF EUGENE G. SCHULZ.

Temporary burial of Colonel Welborn B. Griffith Jr. at Saint-Corneille, France, August 17, 1944. COURTESY OF EUGENE G. SCHULZ.

Colonel Welborn B. Griffith Jr.’s body, covered by US flag and flowers, next to the street in Lèves, France, on which he was killed, with chairs on which villagers sat vigil all night, waiting for Americans to retrieve the body. COURTESY OF THOMAS N. GRIFFIN.

Ceremony posthumously awarding the Distinguished Service Cross to Colonel Welborn B. Griffith Jr. by pinning medal onto the coat of his widow, Nell Griffith, at Fort Hamilton, Brooklyn, New York, November 1944. COURTESY OF ALICE IRVING.

Blown-out temporary replacement windows in Chartres Cathedral, 1944. Achille Carlier (1903–1966), architect. Photography from figure 21 in “Le drame des vitraux des Chartres pendant la guerre,” Les pierres de France 13 (April–June 1950). Window bays of the nave of Chartres Cathedral, after the complete removal of stained-glass windows in 1939. Inv. no. page 30 07R03701. © MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE / MÉDIATHÈQUE DE L’ARCHITECTURE ET DU PATRIMOINE, DIST. RMN-GRAND PALAIS / ART RESOURCE, NY.

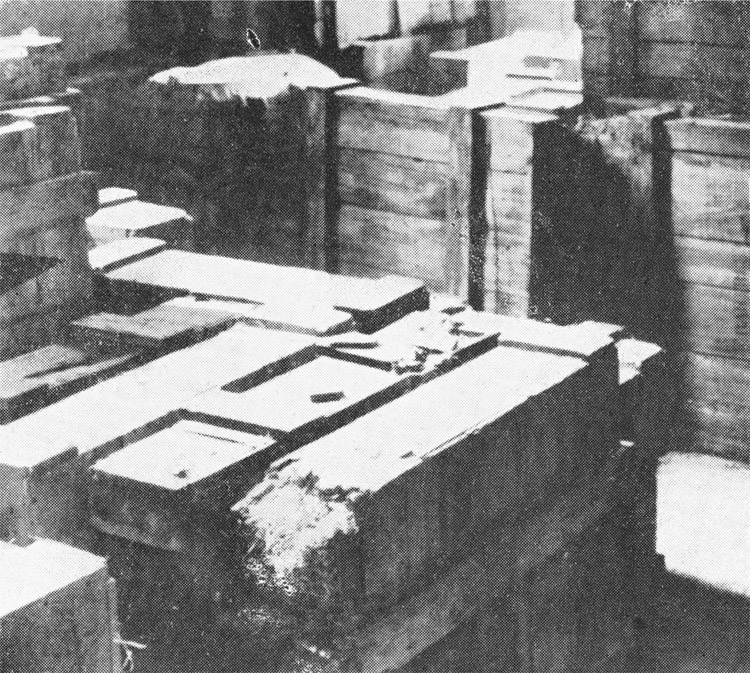

Wooden crates holding window panels in storage in 1946, one revealing water damage. Achille Carlier (1903–1966), architect. A copy of this image appeared as figure 23 in “Le drame des vitraux des Chartres pendant la guerre,” Les pierres de France 13 (April–June 1950), 31–35. Boxes containing the stained-glass windows of Chartres Cathedral, deposited in 1939, stored in the quarries of Château de Fongrenon in the municipality of Cercles (Périgord), 1940. Positive monochrome on paper. © MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE / MÉDIATHÈQUE DE L’ARCHITECTURE ET DU PATRIMOINE, DIST. RMN-GRAND PALAIS / ART RESOURCE, NY.

Choir and altar of Chartres Cathedral in winter 1944–1945 and 1945–1946. COURTESY OF LES ARCHIVES DÉPARTEMENTALES D’EURE-ET-LOIR.

Plaque honoring Colonel Griffith, mounted in Lèves, France, on the building in front of which he died. Translated into English, it reads, “Here was killed on August 16, 1944, the American colonel Welborn B. Griffith.” COURTESY OF EUGENE G. SCHULZ.

Distinguished Service Cross. PHOTO: SHISCHKABOB.