Part 2

Philippians 1:12–26

Narratio: The Present and Future Advance of the Gospel

Introductory Matters

The body of the ancient letter frequently began with the disclosure formula, “I want you to know” (cf. Rom. 1:13, “I want you to know”; 2 Cor. 1:8, “I do not want you to be ignorant”). Paul adopts this formula in Phil. 1:12 to inform the readers of recent developments. “What has happened to me” (ta kat’ eme) is an oblique way of referring to Paul’s imprisonment (desmoi, lit. “bonds, fetters”), to which he alludes elsewhere (1:7, 13–14, 17). The Philippians have heard about his imprisonment, which, along with their own sufferings (1:28–29), is a source of anxiety. Paul indicates in 1:18–26 that he is uncertain of the outcome—that a death sentence is possible. The references to the praetorian guard (1:13) and Caesar’s household (4:22) indicate his encounter with Roman power.

The letter gives no clear indication of the place or conditions of Paul’s imprisonment. Prison conditions varied widely, often depending on the status of the prisoner (Wansink 1996, 41–43). Some prisons were dark dungeons, while others included the house arrest described in Acts 28:16–31. Paul’s prison, like many others in the Roman world, was a holding place for those who were awaiting trial. He probably did not suffer the worst abuses associated with imprisonment, as evidenced by his reception and sending of messengers and writing activity. Nevertheless, he was under the watchful eye of the praetorian guard (NRSV “imperial guard”) and known to those of Caesar’s household (4:22).

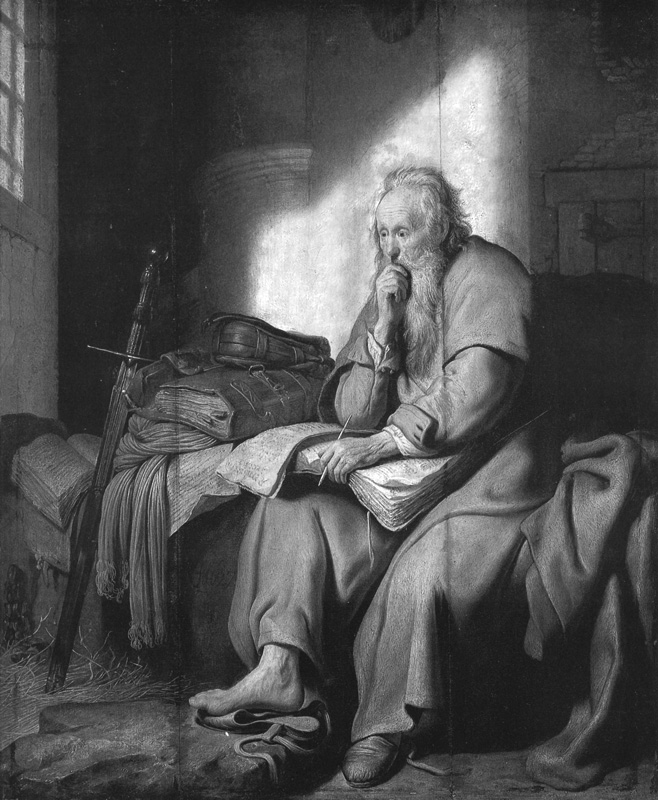

Figure 5. Rembrandt’s depiction of Paul in prison [Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons]

Both Acts and the letters indicate that Paul was imprisoned multiple times (Acts 16:22–24; 24–26; 28:16–31; 2 Cor. 6:5; 11:23). The references to the praetorium (praitōrion) and to Caesar’s household (4:22) provide no clear indication, for both could have been used for Roman outposts. The term praitōrion is used in a variety of ways—for the governor’s residence in localities such as Judea (cf. Matt. 27:27; John 18:28, 33; 19:9) or the imperial palace in Rome. In other ancient texts it refers to the body of troops which comprised the praetorian guard (cf. Lightfoot 1888, 101). The reference to “everyone else” suggests that Paul is referring to Roman soldiers rather than to a specific location. His reflections about life and death (1:20–24) suggest that Paul is in Rome awaiting the verdict on his life.

Interpreters have debated the identity of those who preach Christ from envy and rivalry and selfish ambition (1:15, 17) and those who wish to increase Paul’s suffering in imprisonment (1:17). Some have identified them with the Judaizers in 3:2 or other opponents. However, the carefully balanced contrasts between those who preach from goodwill and love and those who preach out of envy, rivalry, and selfish ambition—all common vices (2:3–4; Gal. 5:19–21)—correspond to Paul’s style throughout the letter. He employs contrasting models of good and bad behavior to emphasize the appropriate models (cf. 2:21–22; 3:2–3; 3:18–21) throughout the letter (cf. Davis 1999, 66). They are “brothers in the Lord” (1:14), and they “preach Christ” (1:15, 17). Thus the focus is not on the identity of the opponents but on the advance of the gospel.

In comparing the two potential outcomes of his imprisonment (1:18–26)—life or death—Paul “verges on soliloquy” (Dailea 1990; Croy 2003, 518) that is filled with echoes of ancient discussions of the topic. In the OT, Jonah cries out, “Now, O LORD, please take my life from me, for it is better for me to die than to live” (Jon. 4:3 NRSV). Both Moses (Num. 11:14–15) and Elijah (1 Kings 19:4) cry to God to take their lives (Gupta 2008, 257). The comparison of life and death was a familiar theme in philosophical discussion. Synkrisis was a common rhetorical device in which the speaker compared either individuals or subjects, distinguishing either between the good and the bad or between the good and the better. The anthologist Stobaeus gathered sayings under the title “About Life and Death.” Here Paul compares the good and the better, introducing the topic with the assurance that “Christ will be magnified” in his “body, whether through life or death” (1:20). The passage suggests his uncertainty over the outcome of his imprisonment: whether he will be executed or set free.

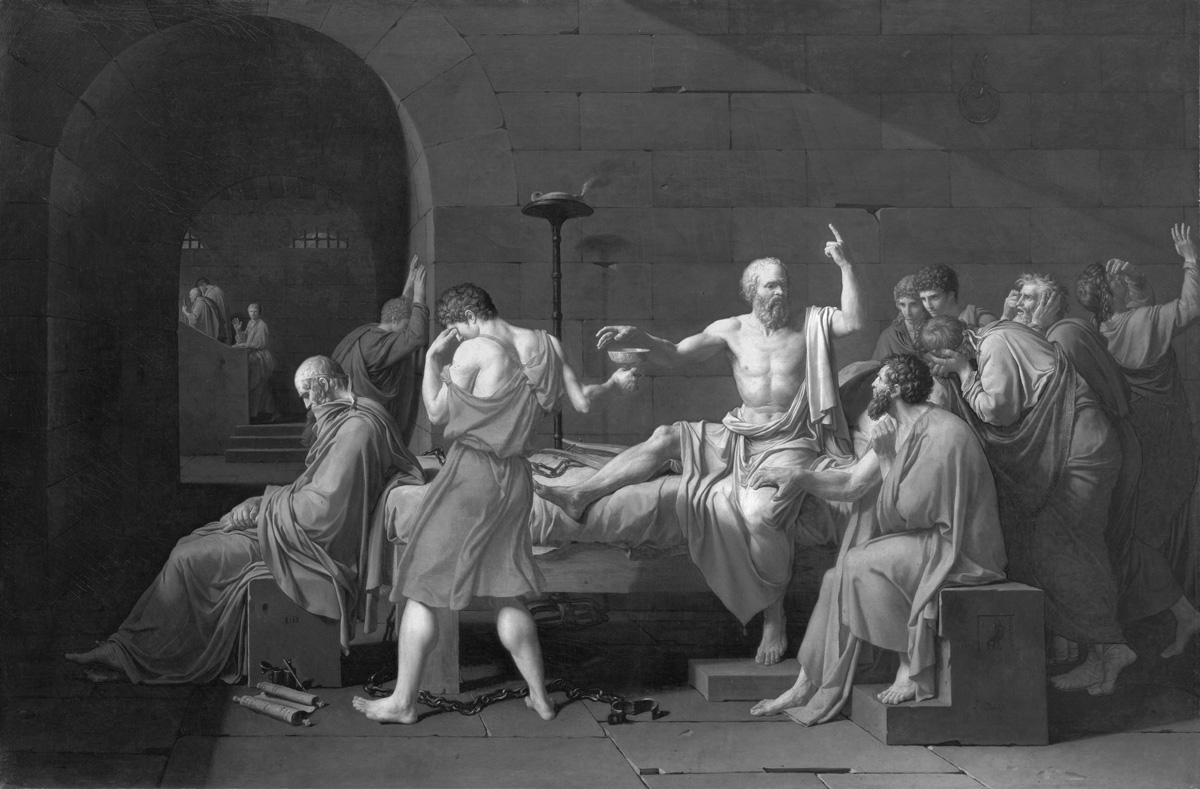

Figure 6. Artist’s depiction of the death of Socrates [Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons]

Paul elaborates on the way in which Christ will be magnified in 1:21–26. “To live is Christ and to die is gain” (1:21) expands on the reference to life and death in 1:20. Paul further expands this alternative, indicating that “to live is Christ” is to live in the flesh (1:22) and remain with the Philippians (1:24–26); “to die is gain” is to “depart and be with Christ” (1:23).

“To die is gain” (kerdos) recalls numerous sayings in antiquity in which death is a gain. Telemachus cries out at the evils in the palace of his parents, “But if you are minded even now to slay me myself with the sword, even that would I choose, and it would be better [kerdion] far to die than continually to behold these shameful deeds” (Homer, Od. 20.16, A. T. Murray, LCL). According to the collection in Stobaeus (4.53.27), “It is better to end this life than to live wickedly.” Isocrates (Archid. 89) says, “To end this life is better than to live in dishonor.”

The death of Socrates was known everywhere. Socrates says, “And if there is no consciousness, but [death] is like a sleep, when the sleeper does not even see a dream, death would be a wonderful gain” (Plato, Apol. 40c–d). He adds, “So if that is the sort of thing death is, I count it a gain” (Plato, Apol. 40e). Death is a gain because it is preferable to a hateful life (Euripides, Medea 145–47), a life of trouble (Euripides, Medea 798–99), or a life that is useless (Euripides, Hercules furens 1301–2). Death is a gain because it brings freedom from misery. To die in battle is a gain (Pausanias 4.7.11; cf. Josephus, Ant. 15.158) compared to the alternative. Death can either be a “gain” because the alternative is a life of shame or misery or because of the anticipation of future bliss (Vollenweider 1994, 248–49). While Paul employs the Greek topos on life and death, his perspective is different. Unlike the ancient writers, he does not regard death as a gain in comparison with a dishonorable or miserable life, but the choice between the good and the better.

Paul’s statement, “I do not know what I will choose” (hairēsomai, NRSV “prefer”) recalls the numerous statements in which individuals choose between life and death (Vollenweider 1994, 250), claiming that death is preferable to life. The rendering of hairēsomai as “choose” (ASV, RSV, NIV) corresponds to ancient Greek usage, suggesting that Paul has a decision between life and death. Some interpreters (e.g., Droge 1988, 262–86), therefore, maintain that Paul contemplates suicide. Indeed, suicide was a common choice among prisoners in antiquity (Wansink 1996, 58–59). Vollenweider cites a variety of ancient passages that use forms of haireō to describe a choice between life or death (1994, 250). While no evidence exists that Paul contemplated suicide, he did, however, have a choice between a rigorous defense and the passive acceptance of his death. One of the great examples of such a choice is that of Socrates, who says, “I will choose [hairēsomai] to die rather than to live begging meanly and thus gaining a life far less worthy in exchange for Death” (Xenophon, Apol. 9; cf. Plato, Apol. 38e, cited in Wansink 1996, 121). Similarly, the four Gospels report the trial and death of Jesus, who chose not to answer his accusers. Thus Paul’s choice is likely between defending himself or living to serve others.

Paul formulates his personal preference of dying, echoing widely disseminated aphorisms that were deep in the consciousness of his contemporaries (Vollenweider 1994, 255). Using these aphorisms, he hopes to gain understanding from the Philippians and reconcile them to his death. The basic tone of the citations introduced is pessimistic: dying and death are better in comparison with pain and suffering, which darken life (Vollenweider 1994, 255). Paul does not proceed from general thought about negativity of existence but places his reflections in the shadow of the cross (Vollenweider 1994, 255). The gain of death for Paul is not simply the redemption from earthly life but life with Christ. Thus, while Paul takes up the language of his culture, he distinguishes himself from the Greeks in that he does not denigrate earthly life or flee from it (Gnilka 1968, 74).

Ancient readers would probably have heard in Paul’s “desire to depart and be with Christ” (1:23) an echo of Socrates’s desire to die and “be with the gods” (Phaed. 69c; cf. 81a). Interpreters have debated how Paul’s statement is consistent with his eschatological views elsewhere. According to 1 Thess. 4:13–18, Paul anticipates the return of Christ in his own lifetime. The dead in Christ will arise and Christians who are alive will be caught up with him. Similarly, in 1 Cor. 15:50–58 he anticipates the end when all will be changed, and the perishable body will put on the imperishable. Many scholars have explained the tension between Paul’s expectation in Phil. 1:23 and his hope for the return of Christ assuming that, with the delay of the parousia, Paul altered his views from the apocalyptic expectation of the end of the world to the individualized view of the future existence reflected in 2 Cor. 5:1–10 and Phil. 1:23. This would be the turning away from Jewish apocalyptic to a Greek view of the immortality of the soul. Others have suggested that Paul assumes an intermediate state of the dead before the return of Christ. However, this development in Paul’s eschatology is unlikely, for Paul refers at numerous points in Philippians to the “day of Christ,” using language that is consistent with the other letters (Phil. 1:6, 10; 2:16). Paul anticipates a time when God will “transform the body of our humiliation that it may be conformed to the body of his glory” (Phil. 3:21).

Jewish apocalyptic writers frequently spoke both of individual eschatology and the end of the world without demonstrating the consistency of these concepts. In the same way, Paul does not attempt to provide a detailed description of the end-time, for his concern is not to describe how the end takes place, but to affirm his hope (cf. G. Barth 1996, 339; Schapdick 2009, 33).

Tracing the Train of Thought

The Advance of the Gospel in the Present (1:12–18a)

1:12–18a. With the disclosure form I want you to know, brothers [and sisters] (1:12), Paul turns from his prayer for the church to his own situation as a prisoner, which was undoubtedly a cause for anxiety among the Philippians. His report has little resemblance to ancient prison letters, which described in detail the self-centeredness, suffering, and isolation of the prisoner (Bloomquist 1993, 69). Paul says little about his own situation, however, but counters their fears with the conviction that what has happened to [him] will, to the contrary (mallon, NRSV “actually”), result in “the advance [prokopē] of the gospel” (NRSV “helped to spread the gospel”). Mallon here is rendered “to the contrary” because it indicates that Paul is correcting the expectations of the Philippians. This claim would have been a surprise to the Philippians, who would have judged from appearances that the gospel was in jeopardy. Prokopē (advance) was used synonymously with auxēsis (growth), and was commonly used for the individual’s advancement in knowledge or ethical sensitivity (cf. 1 Tim. 4:15). It became a technical word among the philosophers for the individual’s moral advancement. It was also used for the advancement of an army (cf. Josephus, Ant. 3.42; 2 Macc. 8:8) and for the increase in military power (Polybius, Hist. 3.4.2). Among the undisputed letters of Paul, the word appears only in Phil. 1:12, 25, forming the frame for 1:12–26 and providing the essential focus for this section. The advance of the gospel evokes the image of a movement that, like an advancing army, continues to go forward. With Paul’s imprisonment the gospel will reach more people than would have been possible otherwise (Giessen 2006, 232).

With the disclosure form, “I want you to know,” Paul is not informing the Philippians about his imprisonment, to which he has already referred (1:7), but offering his own perspective on his suffering. This autobiographical section prepares the way for the exhortation in 1:27–2:18, as Paul describes his own attitude toward suffering before he instructs the readers on their response to suffering. In Philippians, as in other letters, autobiographical reflections precede the exhortations (cf. 1 Cor. 1:18–2:5; 2 Cor. 1:15–2:13; Gal. 1:11–21; 1 Thess. 2:1–11).

Autobiography plays an especially important role in Philippians, as Paul presents himself as a model for his readers to imitate (3:17; 4:9). Consistent with ancient rhetorical theorists, Paul knows that the appeal to his own ethos is a persuasive argument. The argument from ethos indicates that speakers exemplify what they commend to others. Thus Paul is a model of the hope and joy that sustain him. His positive evaluation of suffering prepares the way for his instruction urging them to accept the suffering that necessarily accompanies faith (Wojtkowiak 2012, 270).

As the inclusio in 1:12, 25 indicates, Paul’s focus is the advance (prokopē) of the gospel (1:12) and the Philippians’ “advance and joy of faith” (1:25). Paul delineates this assurance of advancement in two ways. In 1:12–18a he speaks of recent events and their impact on the present, concluding his thought with in this I rejoice. In 1:18b–26 he turns to the future tense, introducing his thought with “I will continue to rejoice” (1:18b). Thus Paul employs a rhetorical strategy that was well known in antiquity by interpreting every negative fact in a positive way (Vos 2005, 279–81). Like military leaders who instilled courage in the midst of desperate conditions by claiming that the other side was in retreat, Paul argues that the gospel is advancing, with the difference that Paul is confident of ultimate victory. He looks to recent events and concludes with thoughts on the future as a response to the Philippians’ fears for the future. He is sure that recent events are evidence not of the failure of the gospel but of its advance in both the present and the future. Despite current appearances, the advance of the gospel is already taking place.

Paul offers evidence that his imprisonment will result rather in the advance of the gospel (1:12). In the first place, his bonds have become known throughout the whole praetorian guard (1:13). This hyperbole suggests that, by Paul’s imprisonment, Roman authorities have become aware of his mission. He does not mention the success of this public awareness but says only that his bonds have become manifest. All of the others probably refers to the wider circles around the praetorian guard. Thus the advance of the gospel is the spread of the word even among Roman authorities.

The advance of the gospel is further evidenced in the fact that most of the brothers [and sisters] in the Lord have been persuaded by Paul’s bonds to speak the word of God without fear (1:14). Paul’s imprisonment has given them the courage to speak and to follow his example. To speak the word of God (1:14) is the equivalent of preaching Christ (1:15) or proclaiming Christ (1:17–18). What follows is a reflection on the motives from which they preach. Paul neither names anyone nor indicates that their preaching is false. In fact, he offers this as an example of the advance of the gospel. In a chiastic manner (ABBA), Paul reflects on those who proclaim the gospel.

A Some preach Christ because of envy (phthonos) and strife (eris),

B while others preach from goodwill (eudokia),

Bʹ Some preach from love, knowing that I am destined for the defense of the gospel,

Aʹ Others preach Christ from selfish ambition (eritheia), not sincerely, thinking that they will add affliction in my chains.

The description corresponds to the vices and virtues that Paul frequently contrasts (cf. Gal. 5:19–23; Phil. 2:3–4). His hortatory strategy throughout Philippians is to describe contrasting models of behavior, hoping that his readers will choose the appropriate behavior (3:2–3, 17–21). Envy (phthonos) is among the vices that Paul lists in Rom. 1:29 as characteristic of unrighteous humanity, and it is a vice to be put away as one of the works of the flesh (Gal. 5:21; cf. also 1 Tim. 6:4; Titus 3:3; 1 Pet. 2:1). Strife (eris) is also among the vices of unrighteous humanity (Rom. 1:29) and appears frequently in Paul’s vice lists (Rom. 13:13; 2 Cor. 12:20; Gal. 5:20; cf. 1 Tim. 6:4; Titus 3:9). The term was used in Greek literature for political strife and is frequently used with lists of synonyms (LSJ 689). Selfish ambition (eritheia) appears in 2 Cor. 12:20. Except for two references in Aristotle (Pol. 5.3.1302b4, 1303a4), where it is used for the self-seeking pursuit of political office, it is unknown in Greek prior to Paul (TLNT 1:70) but is commonplace in Pauline ethical instruction (2 Cor. 12:20; Phil. 1:17; 2:3; cf. James 3:14). In Philippians these vices are not compatible with the mind of Christ (Phil. 2:3–5). Love is the predominant ethical value (1:9–11; cf. 2:1). Eudokia here is parallel to love (cf. God’s goodwill in 2:13; God’s goodwill in Eph. 1:5, 9; human goodwill in 2 Thess. 1:11). Paul does not refer to a false teaching but mentions only motives. Ambitious people with impure motives (ouch hagnōs, NRSV “not sincerely”) suppose that they will increase Paul’s suffering in his chains (NRSV “imprisonment”). However, as Paul indicates, they are mistaken in their assumption, for the end result of his imprisonment is that Christ is preached (1:18a). Thus the advance of the gospel is seen not in the results of the preaching but in the gospel’s now becoming known to Roman power and the broader public.

Despite his imprisonment, Paul rejoices (see also 1:4; 2:2, 17; 4:1 for Paul’s rejoicing) because of the advance of the gospel. As he indicates to the Corinthians, he experiences joy in his afflictions (2 Cor. 7:4; cf. Col. 1:24), and he can rejoice when he is weak (2 Cor. 13:9) when he receives good news of the progress of his churches (2 Cor. 2:3; 7:7, 13; 1 Thess. 2:19; 3:9; Philem. 7), his “joy and crown” (Phil. 4:1; 1 Thess. 2:19). This should be an encouragement for the Philippians (Böttrich 2004, 99) and an example to emulate (cf. 2:1–4). Paul is not defeated by his imprisonment or by people who preach with bad motives.

The Advance of the Gospel in the Future (1:18b–26)

1:18b–20. Paul’s imprisonment and ultimate salvation. Paul turns from the recent events that have made him rejoice in 1:12–18a to his anticipation of future rejoicing in 1:18b–26 as he moves from “I rejoice” in 1:18a to “I will continue to rejoice” in 1:18b, introducing the future tense that dominates 1:18b–26. The basis for this joy, as the explanatory for (gar, v. 19) indicates, is his knowledge (I know) about the future that is based on what God has done in the past. Just as he is confident that God will complete his work among the Philippians (1:6), he knows that this (i.e., his imprisonment) will result in salvation. The salvation is not release from prison but the triumph of the gospel, which is advancing through his present circumstances. Paul elaborates on this salvation in 1:18b–20, which is a single sentence in Greek.

Two prepositional modifiers clarify Paul’s reason for rejoicing. First, he indicates the means of this favorable outcome: through (dia) their petition (deēseōs) and the supply of the Spirit of Jesus Christ. The community reciprocates Paul’s petition (deēsis, 1:4) with their own prayers, and they receive the supply (epichorēgias, NRSV “help”) of the Spirit of Jesus Christ. In both Greek and English, the supply of the Spirit is ambiguous, since it can either mean “the supply, which is the Spirit” (objective genitive) or “the supply that comes from the Holy Spirit” (subjective genitive). The parallel in Gal. 3:5 (“The one who supplies [epichorēgōn] you with the Spirit”; cf. Eph. 4:16; Col. 2:19; 2 Cor. 9:10) indicates that the supply of the Spirit is the Spirit himself (objective genitive) rather than the supply that the Spirit gives (Bockmuehl 1998, 84). In secular Greek the term epichorēgia is used for generous public service (BDAG 387) or a husband’s support for his wife (cf. 1 Clem. 38.2; MM 251). Only here does Paul speak of the Spirit of Jesus Christ, which is equivalent to references elsewhere to the Spirit (Rom. 8:4–5; Gal. 3:5; 5:22, 25), Spirit of God (Rom. 8:9), Spirit of Christ (Rom. 8:9), and Holy Spirit (1 Thess. 4:8).

The second prepositional phrase indicates that what Paul knows (cf. 1:25) is not an expression of his calculation (Gnilka 1968, 65) but is according to (kata) his eager expectation and hope. Eager expectation (apokaradokia) is linked with hope in its only other appearance in the NT. In Rom. 8:18–29 Paul describes the “eager expectation” of the creation and the hope in which believers live (cf. H. Balz, EDNT 1:132). Together the two words suggest the intensity of Paul’s expectation, which is a positive model for the Philippians as they worry about the future.

The confidence that “this will result in salvation” is an echo of Job 13:16, to which Paul alludes without indicating that he is citing Scripture. Paul’s imprisonment probably caused him to identify with Job. Both Job and Paul have confidence in the future salvation (sōtēria). Job anticipates sōtēria from illness and death, while for Paul the sōtēria is the ultimate triumph of God when Christ, the Savior (sōtēr), returns (cf. 3:21).

Parallel expressions I will not be ashamed and Christ will be magnified in my body, whether in life or death (1:20) express the future hope in language derived from the Psalms. The psalmist cries, “Do not let those who wait for you be put to shame; let them be ashamed who are wantonly treacherous” (Ps. 24:3 LXX [25:3 NRSV]). According to Isa. 28:16 (cf. Rom. 9:33), “those who believe in him will not be put to shame.” Paul uses the terminology of shame in Rom. 5:5, “Hope is not ashamed, because the love of God has been poured into our hearts.” Shame is not a sense of guilt but, as in the Psalms, the failure to reach the goal (Gupta 2008, 26). Used as an antonym four times in Paul is kauchaomai. When Paul boasts to Titus of the church at Corinth, he is not put to shame (2 Cor. 7:14; A. Horstmann, EDNT 2:258); when he boasts to the Macedonians of their goodwill in the collection, he does not want to be put to shame (2 Cor. 9:4). His ultimate boast will occur when he presents his people blameless before God (cf. 2:16; 2 Cor. 1:14; 1 Thess. 2:19).

Paul knew the OT expression “Let the Lord be magnified” (megalynthētō ho kyrios). The psalmist says,

Let all those who rejoice in my calamity

be put to shame and confusion;

let those who exalt themselves against me

be clothed with shame and dishonor.

Let those who desire my vindication

shout for joy and be glad,

and say evermore,

“Great is the LORD,

who delights in the welfare of his servant.”

(Ps. 35:26–27 NRSV [34:26–27 LXX])

The people say, “May those who love your salvation / say continually, ‘Great is the LORD!’” (40:16 NRSV [39:17 LXX]; cf. 69:30 [68:31 LXX]: “I will magnify him in praise”). Paul says to the Corinthians that God has shamed the wise so that they cannot boast before him (1 Cor. 1:27–29). For Paul, the words of the psalm become a reality in the preaching of Christ, which will occur in all boldness (en pasē parrhēsia, 1:20). As other passages in the NT indicate, parrhēsia is the absence of concealment (cf. 2 Cor. 3:2) and the courage to speak unpopular words to people in power (Acts 2:29; 4:13, 29; cf. 1 Thess. 2:2).

The future hope and Paul’s present ministry are intertwined. When Paul declares that Christ will be magnified now and always (1:20), he speaks both of his present circumstances and the future hope. That Christ is magnified in his body, even in the context of suffering, is a theme elsewhere (cf. 2 Cor. 4:10–11, 16–18). The ultimate salvation is when Christ is magnified in the life beyond death.

1:21–24. Living and dying. Mention of life or death leads Paul to reflect on life and death in 1:21–24. Here he employs motifs that were common in Hellenistic literature. We observe the contrasts:

life or death (1:20)

to live . . . to die (1:21)

to live in the flesh . . . remain in the flesh (1:22, 24) . . . depart and be with Christ (1:23)

“To live” in verse 21 is “to live in the flesh” (v. 22) and “remain in the flesh” (v. 24). To die (vv. 20–21) is “to depart and be with Christ” (v. 23). While Paul echoes Greek reflections on life and death (see under “Introductory Matters”), he does not share the Greek view that death is desirable because it brings an end to an unbearable existence. Nor does he compare the evils of life with the good of death. Instead, he compares the good with what is better, which is an increase in what he has already experienced (Gnilka 1968, 71).

To live is Christ is an epigrammatic way of expanding on the claim that Christ is magnified in his body, whether in life or death, for Christ is the orientation point of his life. The image recalls his statement, “I have been crucified with Christ, . . . and the life that I live in the flesh I live in faith in the Son of God” (Gal. 2:19–20). In Philippians he speaks of sharing in the afflictions of Christ (Phil. 3:10) and of discarding all achievements for the sake of Christ. In the phrase to die is gain (kerdos), Paul employs the commercial image in anticipation of 3:7–10. Having lost all that he had achieved, the ultimate gain is to depart and be with Christ (Giessen 2006, 215).

After describing the two options of life and death (1:20–21), Paul comments on each of them in 1:22–25, elaborating on the first option (to live) with the phrase “to live in the flesh” (1:22). A debate on the syntax and punctuation of 1:22 is reflected in the translations:

But what if my living on in the body may serve some good purpose?

Which then am I to choose? (NEB)

If I am to live in the flesh, that means fruitful labor for me;

and I do not know which I prefer. (NRSV)

If I am going to go on living in the body, this will mean fruitful labor for me.

Yet what shall I choose? I do not know! (NIV)

If it is to be life in the flesh, that means fruitful labor for me.

Yet which I shall choose I cannot tell. (RSV)

If I am to live in the flesh, that means fruitful labor for me.

Yet which I shall choose I cannot tell. (ESV)

Because of the comparison of life and death, the reader expects the conditional clause, If I am to live in the flesh (1:22 [protasis]) to be followed by a then clause (apodosis). The logic of Paul’s argument suggests that he should continue with a comparison to the benefits of dying (i.e., “if I am to die”; cf. Bockmuehl 1998, 90). Instead, he breaks off the comparison in 1:22, exclaiming, I do not know what I shall choose, elaborating on the choice in 1:23. The benefit of his life in the flesh is fruitful labor (karpos ergou). Karpos (lit. “fruit”) is the term for ethical conduct (cf. 1:11; Gal. 5:22; Rom. 6:19, 22) and also a term for the results of Paul’s ministry (Rom. 1:13). Thus Paul envisions continued missionary effectiveness if he remains in the flesh.

The passage also has other puzzling issues of translation. The translation of hairēsomai, rendered “choose” in the NIV and RSV and “prefer” in the NRSV, is a question inasmuch as interpreters conclude that Paul has no choice in the matter. However, the most common meaning of hairēsomai is choose, a term that Paul has selected for rhetorical reasons, suggesting that he patterns himself after the preexistent Christ, who chose to empty himself (2:7; see under “Introductory Matters”). Although the term gnōrizō normally means “make known” in Paul (see Rom. 9:22–23; 1 Cor. 12:3; 15:1; 2 Cor. 8:1; Gal. 1:11; Phil. 4:6) rather than “know” (BDAG 203), here Paul is using the term in the classical sense to indicate that he does “not know” what he will choose (note the translations above).

Paul’s difficult choice is stated in 1:23. I am hard pressed (synechō) between the two options. In its literal sense the verb synechō refers to people, diseases, or powers that “press hard and leave little room for movement” (BDAG 971; cf. Matt. 4:24; Luke 8:37, 45; 19:43; Acts 28:8). According to 2 Cor. 5:14, the love of Christ compels (synechei) Paul to proclaim the message. In Phil. 1:23 Paul is hard pressed between the choice of life and death. The decision is not between good and bad but between what is better (kreisson) for Paul and what is more necessary (anankaioteron) for the church (Gnilka 1968, 73): to depart and be with Christ or to remain in the flesh (v. 24).

The image of a departure (analysis) as a euphemism for death is commonplace in Greek literature. The literal meaning “untie” or “loosen” was a metaphor drawn from the ships that were set loose from their moorings (LSJ 112). The image is used in 2 Tim. 4:6 for Paul’s departure from life, suggesting that death is a journey (cf. Tob. 3:6 BA). While Paul employs an image that appears frequently in Greek and Roman literature (Plato, Phaed. 67a; Epictetus, Diatr. 1.9.16; Cicero, Tusc. 1.74), he does not accept the ancient idea of the soul’s departure from the imprisonment in the body (Gnilka 1968, 73) that is associated with this image. Paul neither elaborates on the details of being with Christ after his death nor indicates how this expectation coheres with his references to the day of Christ (1:6, 10; 2:16) when the Savior returns (3:20–21), for his primary concern is pastoral and rhetorical (see under “Introductory Matters”). He is a model for the Philippians, who are threatened with the possibility of death for the sake of Christ. In keeping with his exhortations to think of others more than oneself (e.g., 2:4), Paul indicates that his choice is for their sakes (1:24, di’ hymas). That is, he recalls the story of Christ in 2:6–11, knowing that Christ gave himself for others. As one who chooses to remain with the Philippians, he exemplifies the life that does not look to its own interests but to the interests of others as he places the interests of the Philippian church above his own. Thus Paul will imitate Christ and serve as a model for the Philippians (Engberg-Pedersen 1995, 275).

1:25–26. Paul’s continuing presence and the joy of faith. Paul elaborates on how his continued existence in the flesh is “more necessary” (1:24) for the Philippians. It is the basis of a conviction about God’s ultimate purposes. Being persuaded of this (touto pepoithōs), I know recalls the earlier statement, “being persuaded of this very thing, that the one who began a good work among you will bring it to completion” (1:6) and the affirmation, “I know that this will turn out for salvation” (1:19). Thus Paul is persuaded because of his faith that God is bringing the church to completion. Indeed, the focus is not on Paul, but on the community, as the predominance of the second-person plural indicates. Paul’s continued existence in the flesh is more necessary “for you” (1:24); consequently he will “remain with all of you” for your advancement and joy of faith (1:24). That is, the benefit to the church is of ultimate importance for Paul, who demonstrates his cruciform love (Gorman 2001, 211). Because God is bringing the church to completion, Paul’s continued ministry is necessary. In a play on words, Paul promises, I will remain (menō) and I will continue (paramenō) with all of you, indicating that he will both live and be present with this church. In mentioning all (cf. 1:3), he emphasizes the unity of the community. Because the community has not yet reached its goal (cf. 1:6), their “advancement [prokopē] and joy in faith” requires his continuing presence. At the beginning of this section (1:12), Paul affirms that his imprisonment serves the advance (prokopē) of the gospel, and now he concludes with a focus on the advance of the community. Prokopē is not the progress of the individual, as it is among the Stoics, but the formation of the community, about which Paul prays in 1:9–11 and to which he gives the ethical instructions that follow (1:27–2:18; 4:1–9). The joy in faith, a major topic in the letter (see 2:18; 3:1; 4:4) and a critical dimension of formation, is a reality for those who look beyond present circumstances to the triumph of God.

In view of the uncertainty about his fate that he expresses in 1:18b–24, Paul’s confidence is surprising. If his more immediate purpose is the advancement and joy of their faith (1:25), his ultimate aim is that their boast (kauchēma) may increase in Christ Jesus through Paul’s presence. This boasting does not have the negative connotations present elsewhere (cf. Rom. 3:27; 4:2; 2 Cor. 10:13; 11:12, 16, 18) but has the positive significance derived from Jeremiah, according to which the believer “boasts in the Lord” (Jer. 9:24; cf. Rom. 5:2–3, 11; 1 Cor. 1:31; 2 Cor. 10:17). Paul’s ultimate ambition is that his churches will be his boast at the end (2:16; cf. 2 Cor. 1:14; 1 Thess. 2:19), and he hopes that his churches will boast in Christ through his presence.

Theological Issues

The transition from Paul’s prayer for the Philippians (1:3–11) to the news of his situation (1:12–26) is not a break in the argument but an expression of confidence that no obstacles—neither the imprisonment of the leader nor the preaching by people who have impure motives—can prevent the completion of God’s work. As the inclusio of prokopē (1:12, 25) indicates, the progress is twofold. It occurs in the continued preaching of the gospel (1:12–18) and in their continued formation (1:25; cf. 1:6). Paul’s hopeful outlook is a demonstration of the phronēsis—the disposition and way of seeing the world—that he hopes to instill in the Philippians. Paul hopes that his perception of his own circumstances will be a model for their response to their own suffering.

Paul assures ancient and modern readers that the progress of the gospel does not depend on having ideal conditions. As Tertullian observed the impact of persecution on the Christian movement, he declared, “We become more numerous every time we are hewn down by you: the blood of Christians is seed” (Tertullian, Apol. 50). Kierkegaard observed the opposite situation in a Christian society, complaining that a Christian society trivializes any sense of discipleship (Kierkegaard 1944, 127; cf. Migliore 2014, 47). While Christian faith declines in the context of economic prosperity in Europe and North America, it grows under oppressive governments and conditions of extreme poverty in Asia and the global South.

Paul is confident that the progress of the gospel does not depend on the purity of the proclaimers. Since the Donatist controversy of the fourth and fifth centuries, believers have debated whether the power of the gospel depends on the purity of the proclaimer. Anticipating the outcome of the later debate, Paul’s joy that “Christ is preached,” even by those whose motives are impure, is a reminder that God works not only through ideal proclaimers but also through those who are weak or have mixed motives.

In his declaration that the progress of the gospel can occur whether he lives or dies, Paul presents one of the earliest reflections on a Christian view of death. He does not welcome death because of the misery of life, as some ancient people did, but because he participates in the story of Christ that progresses from death to life. To die is to continue to be “with Christ.” In his attitude toward death (1:20–26), Paul is a model both for the Philippians and for contemporary believers, both of whom may be shaped by the attitudes of the surrounding culture. Paul challenges a culture that denies death and employs technology to extend life indefinitely with his confidence that death is a gain for those who trust God.

Paul’s desire to depart and be with Christ has puzzled interpreters who have questioned how this hope is consistent with his frequent references to the final day (1:6, 10; cf. 3:20–21). Paul is not concerned to answer questions about the time of the end or the intermediate state of the dead, but to express a confident expectation of the end result when God’s work will be complete. For Paul, as for Jesus (see Mark 13:32), the time of the end is not the major concern. What matters is faithful living until the end (cf. Migliore 2014, 61).