Philippians 2:1–11

The Ultimate Example

Introductory Matters

Paul gives no concrete description of the life that is worthy of the gospel in 1:27–30, but describes it with images suggesting that this existence involves a conflict requiring a united front. In 2:1–11 he describes in more detail the value system that runs contrary to that of the citizens of Philippi. Paul has a special focus on the development of an alternative phronēsis that unites the community. His joy will be complete when they “think the same thing” (to auto phronein), “have the same love,” are “in full accord” (sympsychoi, lit. “united in spirit”; BDAG 961), and are “of one mind” (to hen phronountes, 2:2). Similar terminology is used in Paul’s paraenesis elsewhere. In 2 Cor. 13:11, he urges the readers to “agree with one another” (to auto phronein). The instruction in Philippians is parallel to the paraenesis in Rom. 12:1–15:13 (Sandnes 1994, 152; Engberg-Pederson 2003, 206).

| Philippians | Romans |

| “standing firm in one spirit” (1:27) | “together . . . in one voice” (15:6) |

| “of the same mind” (2:2) | “live in harmony” (15:5) |

| “look not to your own interests” (2:4) | “not to please ourselves” (15:1–2) |

| Jesus as example (2:5) | “For Christ did not please himself” (15:3) |

In Rom. 12:16 (NRSV), Paul instructs the community to “live in harmony with one another” (to auto eis allēlous phronountes), and in 15:5 (NRSV) he prays that God will enable them to “live in harmony with one another [to auto phronein en allēlous], in accordance with Christ Jesus.” Thus phronein is commonplace in Pauline paraenesis in Romans and Philippians.

This command would have resonated with a Greco-Roman audience, which associated it with friendship, a frequent theme among ancient writers, who maintained that “friends think the same thing” (to auto phronein) and are “one soul” (Fitzgerald 1996, 145). According to Cicero (Amic. 15, W. A. Falconer, LCL), the essence of friendship lies in “the most complete agreement in policy, in pursuits, and in opinions.” Dio Chrysostom writes on civic concord to a city torn by factions, challenging his hearers to adorn themselves “with mutual friendship and concord” (Or. 48.2). He asks, “Is it not disgraceful that bees are of one mind [homonousi] and no one has ever seen a swarm that is factious and fights against itself, but on the contrary, they both work and live together, providing food for one another and using it as well” (Or. 48.15, H. L. Crosby, LCL). According to Dio Chrysostom (Or. 34.20), “There are not two people in Tarsus who think alike” (to auto phronountes). Following civil strife in Nicea, Dio delivered a speech in which he appealed to the citizens to maintain peace and friendship toward one another (Or. 39). After complimenting the city on its antiquity and renown (Welborn 1997, 59), he observes, “I rejoice at the present moment to see you having one voice, and desiring the same things.” He adds, “What spectacle is more enchanting than a city with the same mind [homophrosynē]? . . . What city is less liable to failure than that which deliberates the same things?” Then he prays to the gods that

from this day forth they implant in this city a yearning for itself, a love, a single judgment [mia gnomē], and that it desires and thinks the same thing [kai tauta boulesthai kai phronein]; and on the other hand that it cast out discord and contentiousness. (Or. 39.8 LCL, cited in Welborn 1997, 60)

While the terminology would be familiar to a Greco-Roman audience, the content of this moral reasoning (phronēsis) would have been contrary to the Greco-Roman values. Eritheia, already mentioned in 1:17, is a vice that Paul refers to elsewhere (2 Cor. 12:20; Gal. 5:20; cf. James 3:14). In Aristotle (Pol. 5.2.3; 5.2.9), eritheia designates the use of influence in an election with the goal of attaining office, frequently through fraud. Kenodoxia (“vanity,” “excessive ambition,” BDAG 538) appears elsewhere in Paul’s vice lists (Gal. 5:26). The compound refers to the possession of a military post for the purpose of personal advancement. Paul uses the term in vice lists in Gal. 5:19–21 and 2 Cor. 12:20. Tapeinophrosynē (humility) normally has a negative connotation that associates it with service, weakness, obsequious groveling, or mean-spiritedness. In secular Greek it is used for the person who is base, ignoble, and of low birth or works at a low occupation (cf. P.Oxy. 74, “nothing humble or ignoble or despised”). According to Aristotle (Eth. nic. 4.3.1125a2), the tapeinoi are flatterers who grovel before others, hoping to gain an advantage. Epictetus frequently lists the adjective tapeinos among the common vices (Diatr. 1.3.4; 3.2.14; 3.24.43) as a synonym for “ignoble” (1.3.4), “cowardly” (1.9.33), or the status of the slave (3.24.43). This clash of values is evident in Paul’s conflict with the Corinthians, who charge him with being humble (tapeinos) when he is present (2 Cor. 10:1).

The value that Paul places on tapeinophrosynē is rooted in his Christology, for he responds to the charge that he is humble (tapeinos) by appealing to the “meekness and gentleness of Christ” (2 Cor. 10:1). When he encourages his readers to adopt tapeinophrosynē as a way of life, he offers the christological motivation that the preexistent Christ “humbled himself” (Phil. 2:8) at the incarnation (Thompson 2011, 106). Paul’s use of tapeinophrosynē reflects a sharp contrast with the values of Greco-Roman culture, as his debate with the Corinthians suggests. In their eyes he is tapeinos (2 Cor. 10:1) insofar as he does servile work (2 Cor. 11:7) and lacks the boldness to speak openly to his readers.

One does not need to conclude that Paul’s instructions are a response to the problems at Philippi (contra Peterlin 1995, 59). They are probably an essential aspect of community formation that would have been necessary throughout the Mediterranean world, where the quest for honor and status was a paramount value. Cicero observed this central value: “By nature we yearn and hunger for honor, and once we have glimpsed, as it were, some part of its radiance, there is nothing we are not prepared to bear and suffer in order to secure it” (Tusc. 2.24.58). The exhortation “not to look to [one’s] own interests, but to the interests of others” (2:4) is common in Pauline paraenesis (cf. Rom. 12:10; 1 Cor. 10:33; 13:5) and an alternative to Roman values, which would have been especially prominent in Philippi. Paul faces the fundamental tension between common Roman values and the conduct that is worthy of the gospel (1:27; cf. Wojtkowiak 2012, 149).

Paul follows the imperative “Make full my joy” (2:2) with the second imperative, “Have this mind among you” (2:5, touto phroneite en hymin), indicating that to “have the same mind” (to auto phronein) and to “mind one thing” (hen phronountes) is to have “this mind” that he will describe in the narrative that follows. Because no verb is present in the following clause (lit. “which also in Christ Jesus”), translators supply either the verb “is” or “was.” The NRSV renders it, “the same mind . . . that was in Christ Jesus,” suggesting that the following narrative is a call for imitating Christ. The RSV (cf. NIV) renders the phrase “this mind . . . which is yours in Christ Jesus.” Thus interpreters debate the extent to which Paul articulates an ethic of imitation in this passage. Inasmuch as “in Christ” is commonly described as the sphere in which believers live (cf. 1:1; 2:1), the most probable conclusion is that Paul describes a moral reasoning (phronēsis) that belongs to the community that is in Christ. Michael Gorman renders the phrase appropriately: “Have this mindset in your community, which is indeed a community in Christ, who . . .” (Gorman 2001, 43).

“This mind” (2:5) points forward to the narrative of 2:6–11, introduced by “who, being in the form of God.” The main verbs “counted not equality with God,” “emptied himself,” and “humbled himself” describe two stages in the narrative: a downward spiral of descent followed by the third event when “God highly exalted him” (2:9). Paul’s portrayal of Jesus consists of three progressively degrading positions of social status, as Jesus descends from equality with God (status 1) to “the form of a slave,” the equivalent of the “likeness” (homoiōma) and “form” (schēma) of a man (2:7; status 2) to the public humiliation of the cross (status 3; Hellerman 2005, 130). Although almost every line of 2:6–11 is disputed, the basic narrative of descent and ascent is not in question.

The theme of the descent and ascent of Christ appears elsewhere in Paul as a motivation for ethical conduct. He motivates the Corinthians to participate in the collection, reminding them that though Christ was rich, for our sakes he became poor, in order that we might become rich (2 Cor. 8:9). He appeals to the Romans not to please themselves, adding “for Christ did not please himself” (Rom. 15:1, 3). According to Rom. 8:3, “God sent his son in the likeness of sinful flesh,” but Christ is now at the right hand of God above all cosmic powers (8:32–38). Paul develops the theme of the triumph of the exalted Christ over the cosmic powers in 1 Cor. 15:20–28. These themes are also present in John 1:1–18; Heb. 1:1–4; and Col. 1:15–20, all of which tell the story in a poetic style of the descent and ascent of the exalted Christ.

The poetic qualities and the vocabulary of 2:6–11 distinguish it from both its context and other Pauline writings. The rhythm is evident in the parallelisms and the alternation between participles and main verbs. The words harpagmos (NRSV “something to be exploited”; RSV “a thing to be grasped,” 2:6), “form” (morphē, 2:6, 7), and “highly exalted” (hyperypsoō, 2:9) do not appear elsewhere in Pauline literature. Other words are used in a way that they are not used elsewhere (e.g., schēma, “form” [cf. 1 Cor. 7:31]; kenoō, “empty” [cf. Rom. 4:14; 1 Cor. 1:17; 9:15; 2 Cor. 9:3]). Taken together, this usage has suggested to many scholars that Paul is not the original author of 2:6–11 (Tobin 2006, 91–92) but has adapted a preexistent hymn into his letter.

In 1928 Ernst Lohmeyer noted these distinctive features and argued that the passage is a pre-Pauline hymn (Lohmeyer 1961), which Paul incorporated into the letter. Lohmeyer set the agenda for the subsequent discussion of the passage. Three issues have occupied scholarship on Phil. 2:6–11.

1. The structure and genre of the passage. Lohmeyer maintained that the passage is a hymn consisting of six strophes, each with three lines, and that each strophe contains a main verb. The six strophes are divided into two equal parts, with dio (therefore) dividing the two halves of the passage (Lohmeyer 1953, 90). Joachim Jeremias observed the use of parallelism, arguing that the poem consists of three strophes, each with four lines (1963, 186–87). Jeremias correctly noted that the first two strophes begin and end with participles (“being in the form of God . . . taking on the form of a slave”) and that the third line in each is the main verb (“he emptied himself,” “he humbled himself”). While his third strophe has two main verbs (“God highly exalted him,” “he gave to him a name”), it does not fit the pattern of the first two strophes. The absence of unanimity on the arrangement suggests that one must be cautious in calling this passage a hymn. Undoubtedly it has a rhythm, which consists of the alternation between participles and main verbs. It elaborates on the narratives that are present in other passages. The passage may be described more appropriately as a poetic narrative.

2. The conceptual world of the passage. Scholars also debate the conceptual world to which the poetic narrative belongs. Ernst Käsemann proposed the existence of a Gnostic redeemer myth (1968, 45–50), according to which the primal man descends to earth to rescue humanity, a view that has been largely abandoned. Vollenweider has observed that the theme of deities who change their form and visit the earth is common in the Greco-Roman world (2002a, 289). The locus classicus for this view is the statement in Homer’s Odyssey that “the gods in the guise of strangers from afar put on all manner of shapes, and visit the cities” (Od. 17.485–86). Dionysus, appearing in the mask of his own prophet, says, “I exchange my form for that of a human” (Euripides, Bacch. 4). Jupiter and Mercury visit the world “in mortal form” (Ovid, Met. 8.626–724). Especially noteworthy are the stories in which the gods must serve among mortals. Apollo and Poseidon suffer this fate under Laemedon (Ovid, Met. 11.202–3). These stories have only a superficial resemblance to the narrative of the one who “emptied himself,” took the form of a slave, and submitted himself to public humiliation.

A common theme in Greco-Roman literature is the transformation of a god into a man and his subsequent exaltation. Horace combines the ruler’s equality with God with an epiphany on earth, identifying Octavian with the epiphany of Mercury, who becomes transformed and appears as a young boy (Horace, Carm. 1.2.41; cited in Wojtkowiak 2012, 90). Ovid speaks of Caesar as one who spent his allotted time on earth, but then as a god entered heaven and his place among the temples on earth (Met. 15.815–20). Ancient readers would probably have recognized the parallel themes of the transformation into a human followed by the deity’s return to heaven and worship on earth.

More likely is the proposal that the OT and Jewish wisdom literature play a role, as they do in the other narratives of descent and ascent. Wisdom is the “image of God” and “reflection of God” (cf. Wis. 7:25–26). Philo identifies wisdom with the logos, the image of God (Conf. 97, 147; Fug. 101). This theme probably originated among Hellenistic Jews. The “image of God” and the “reflection of God” are equivalent to the “form of God” (cf. R. Martin 1997, 108).

Richard Bauckham has observed echoes of the suffering servant songs (Isa. 52–53) in this poem. The descent and humiliation of the servant followed by exaltation (Isa. 52:13–53:12) parallels the sequence in Phil. 2:6–11 (Bauckham 1998, 135; Gorman 2001, 90). Indeed, the narrative of Phil. 2:6–11 concludes with the acclamation that “every knee shall bow . . . and every tongue confess” as Lord the one who once suffered the humiliating death on the cross (Phil. 2:10–11).

3. The meaning of harpagmos: A possession to exploit or an object to grasp? A major debate among interpreters concerns the meaning of ouk harpagmon hēgēsato, which the NRSV renders “did not regard . . . something to be exploited” and the RSV renders “did not count . . . a thing to be grasped.” Harpagmos, which is not used elsewhere in the Septuagint or the NT, can mean “a violent seizure of property” or a grasping of something that one already has (BDAG 133). Some interpreters have suggested that the imagery indicates that Christ was less than equal to God and, in contrast to Adam, chose not to grasp it. R. W. Hoover maintains that the classical parallels indicate that harpagmon hēgēsato is an idiom that consistently refers to something that is already present and at one’s disposal (Hoover 1971, 118). Dio Chrysostom uses the verb harpazō to describe improper ways of using authority in contrast to the behavior of the ideal ruler (Or. 4.95). Both the linguistic evidence and the larger context indicate that Christ chose not to grasp what he already had but “emptied himself” of this status. As N. T. Wright has argued, “Over against the standard picture of oriental despots, who understood their position as something to be used for their advantage, Jesus understood his position to mean self-negation, the vocation described in vss. 7–8” (Wright 1991, 83).

4. The political significance of the passage. Recent scholars have noted the political implications of this narrative. The description of one who was “equal to God” and “did not count equality with God a thing to be exploited” has echoes of Roman emperors, who were recognized as “equal to God” and exploited this status. Nearly every description of the emperors of the first century depicts them as “grasping their power through self-assertion, greed, rivalry, violence, and murder” (Tellbe 2001, 256). Thus ancient readers would have thought the idea of a ruler’s abandonment of his privileges strange (Wojtkowiak 2012, 155). The self-emptying of Christ is the antithesis of the self-exalting Hellenistic ruler (Vollenweider 2002b, 283).

Both the OT and Greco-Roman sources describe arrogant rulers who exalt themselves to divine status. Isaiah announces the fall of the king of Babylon, who had said, “I will ascend to heaven; I will raise my throne above the stars of God. . . . I will make myself like the Most High” (Isa. 14:13–15 NRSV). Ezekiel proclaims the fall of the prince of Tyre, who had compared his mind to the mind of God (28:6) and had said, “I am a god” (28:1, 9).

Rulers in the ancient world claimed divine prerogatives and were honored as “equal to God.” A second-century papyrus asks, “What is a god? Exercising power. What is a king? One who is equal to God” (Pap. Heid. 1716.5; Hellerman 2005, 133). According to Aeschylus, Darius is described as “equal to the gods” (isotheos, Pers. 857). Cassius Dio (51.20) reports that the senate decided that the name of Caesar “would be written in the hymns alongside the gods” (auton ex isou tois theois esgraphesthai; TLNT 2:231–32; Standhartinger 2006b, 370–71). Philo describes Caligula’s claim to divine honors. He first identified himself with the demigods Dionysus and Heracles (Legat. 77). “Filled with envy and covetousness, he took possession wholesale of the honors” of the deities themselves (Legat. 80). He identified himself with Hermes, adorning himself with a herald’s staff, sandals, and a mantle (Legat. 94). He also dressed as Apollo, his head encircled with garlands of the sun rays (Legat. 95). Philo objects to Caligula’s claims, concluding that “a divine form [morphē] cannot be counterfeited as a coin can be” (Legat. 110; cited in Wojtkowiak 2012, 90).

Conflict between the new community and Rome is nowhere more present than in the confession that “Jesus Christ is Lord” (Phil. 2:11). The acclamation, drawn from Isa. 45:23, applies to the exalted Christ the term that the prophet and other OT writers use for God. This identification of Christ with the kyrios (Lord) of the OT began in the earliest days of the Aramaic-speaking church (Hellerman 2005, 151) and continued as the Christian confession (cf. 1 Cor. 8:6; 2 Cor. 4:5). New Testament writers frequently cited LXX Scriptures referring to God as the kyrios as references to Christ (cf. Joel 3:5 [2:32 Eng.]; Acts 2:21, 34–39; Rom. 10:13) while also citing passages where the kyrios is God. Indeed, as the confession in Phil. 2:11 indicates, the church continued to distinguish the exalted Lord from God, inasmuch as it was God who exalted the one who had “emptied” and “humbled” himself.

By the time that Paul wrote Philippians, kyrios had become a common title for the emperor. This confession played a vital part in creating opposition between the Christian community and the Roman populace. Inscriptions attest to the use of the term for Claudius (P.Oxy. 1.37.5–6) and Nero (SIG 2.184.30–31, 55). The claim that every knee will bow and every tongue confess that Jesus is Lord (2:10–11) conflicts with the claims of the emperor’s universal sovereignty.

The passage undoubtedly had political implications. The community that has formed its own commonwealth as an alternative to the Roman state worships the one who is kyrios, a term that was widely used for the emperor. This kyrios, however, is the antithesis of the Roman kyrios. He did not exploit his status as one equal to God, as Roman emperors did, but emptied himself of his prerogatives.

Tracing the Train of Thought

A Reversal of Values (2:1–4)

2:1–4. In the first of the proofs (2:1–11), Paul reiterates the thesis statement (2:1–4) and develops the argument, as therefore (oun) indicates (2:1). Two imperatives (2:2, make my joy complete; 2:5, have this mind among you) indicate the behavior that is necessary for the alternative polis, which Paul describes in greater detail in two highly poetic sections (2:1–4; 2:6–11), with 2:5 functioning as a bridge between them.

In 2:1–4 Paul describes the behavior in the alternative polis in a poetic form composed of three strophes, which constitute one sentence in Greek:

If there is any encouragement (paraklēsis) in Christ,

if there is any consolation (paramythia) of love,

if there is any partnership (koinōnia) in the Spirit,

if there is any compassion (splanchna) and mercy (oiktirmos)

make my joy complete, in order that

you have the same mind (to auto phronēte),

having the same love (agapē),

being of full accord (sympsychoi),

having one mind (hen phronountes),

A not with selfish ambition (eritheia) or conceit (kenodoxia),

B but with humility considering one another better than yourselves,

Aʹ not looking to your own interests,

Bʹ but to the interests of others.

This section is distinguished by the carefully arranged parallelism (2:1) and antitheses (2:2–4; cf. 1:15–18; 3:2–4, 17–19). The first strophe, with the four parallel ei tis/ti (“if there is any”) clauses (the NRSV omits all but the first ei tis), provides the foundation for the appeal that follows. “If” in this clause means “since”; thus it should be read, “If, as indeed the case is . . .” (cf. the similar construction in Gal. 5:25; Black 1985, 301). The four parallel clauses, of roughly equal length, indicate the present reality of the community and the basis for the requests that follow. “Encouragement” (paraklēsis) has connotations of both comfort (cf. 2 Cor. 1:3–7) and exhortation (Rom. 12:8; 15:4–5; 1 Thess. 2:3). The term is related to the verb parakaleō, Paul’s usual word for making a polite request (cf. Rom. 12:1; 1 Cor. 1:10; 2 Cor. 6:1–2; Phil. 4:2). Although the emphasis may vary in different contexts, the aspects of comforting and encouraging cannot be rigidly distinguished (Thompson 2011, 55–57). This comfort comes only from being in Christ.

Paul probably includes the phrase “in Christ” first in this list because existence “in Christ” is central to the believers’ identity. This phrase forms an inclusio with 2:5, the description of the believers’ existence in Christ. Although “in Christ” can be used in a variety of ways by Paul, the most basic meaning is that Christ is the realm in which believers live because they have been baptized into Christ, died with Christ, and now live in Christ. As Paul develops this theme elsewhere (see 1 Cor. 12:12–26), to be in Christ is to be in the body of Christ.

Consolation (paramythion) often appears alongside encouragement (paraklēsis, 1 Cor. 14:3; 1 Thess. 2:12; cf. 2 Macc. 15:8–9), overlapping with paraklēsis but also having the additional connotation of consolation for those who are grieving (cf. John 11:19) or the support for the fainthearted (1 Thess. 5:14). This consolation grows out of the love that is already in the community and for which Paul prays (Phil. 1:9–11).

The partnership in the Spirit (koinōnia tou pneumatos) establishes solidarity in the community. The Spirit is the gift of the new age and the empowerment for ethical living (cf. Rom. 8:1–17; Gal. 5:16–25). Paul assumes that compassion and mercy (splanchna kai oiktirmos) already exist in the community, just as his compassion (splanchna) extends to them (1:7).

On the basis of their progress, for which Paul has already given thanks (1:3–11), Paul urges the response when he adds “make my joy complete” (2:2). He has already expressed his joy in the Philippians (1:4), and he has expressed both his present and future joy in the context of his imprisonment and possible death sentence (1:18). The church is his joy (4:1), and he finds special joy in the moral progress of his congregations. His pastoral ambition, as he says on numerous occasions, is the transformed community (cf. 2 Cor. 1:14). In this instance he indicates the nature of this transformation in the four qualities mentioned in 2:2, introduced by the purpose clause (hina, “so that you may be,” 2:2). Once more, Paul employs parallelism (cf. 2:1) to emphasize the moral qualities he encourages. As the use of phron- in the first and fourth items in the list indicates (to auto phronēte . . . hen phronountes), a community with a shared phronēsis (moral reasoning) is his goal. They are of “the same mind” and of “one mind,” living up to the highest ideals of friendship. Between these references to the shared phronēsis, Paul includes “the same love” alongside compassion and mercy. He has already prayed that their love will increase (1:9), and now he encourages the same love, a phrase he uses nowhere else. Compassion and mercy are almost indistinguishable in Paul. These qualities are directed to the community’s common life.

In the ABAB pattern of 2:3–4, Paul alternates the negative and positive qualities that either destroy or unite the community, using two participial phrases. Selfish ambition (eritheia) and conceit (kenodoxia), which appear elsewhere in Paul’s vice lists to describe the conduct that undermines community, are contrasted to humility (tapeinophrosynē). This contrasts Greco-Roman values of self-aggrandizement with a quality that was widely considered a vice in the ancient world. In the second participial phrase, “looking not to your own interests but to the interests of others” (cf. 1 Cor. 10:24; 13:5), Paul offers one of his most familiar ethical instructions. Thus this common phronēsis, or moral reasoning, subverts the values of the Greco-Roman world.

The Mind of Christ (2:5–11)

2:5–11. The second imperative, Have this mind among you, is a bridge connecting the ethical instructions of 2:1–4 and the poetic narrative in 2:6–11. “This mind” recalls the encouragement to “have the same mind” and “one mind” (2:2) and anticipates the following section, indicating that “having the same mind” (2:2) consists of having the mind that Paul will now describe. This is the mind that is “among you” rather than the mind “in you” (NRSV), “this mindset in your community” (Gorman 2001, 43). That is, Paul desires a shared mind-set (phronēsis).

The absence of verbs in 2:5 creates problems, as the alternative readings indicate. According to the NRSV, Paul encourages the readers to have the mind “that was in Christ Jesus,” while the RSV renders the statement “which is yours in Christ Jesus.” Thus translators supply either “was” or “is” to complete the sentence: either the mind that was in Christ Jesus, or the mind that is among the members because they are in Christ Jesus. The past tense suggests that Paul is giving a call for imitation, while the present tense indicates that the focus is not on imitating Christ but on recognizing that the people in Christ have a mind that is rooted in the poetic narrative that follows. While imitation is a dimension of this passage, its focus is the common phronēsis, or moral reasoning, that those in Christ have. “In Christ” forms an inclusio with the same phrase in 2:1 and recalls the earlier identification of the readers as “the saints in Christ Jesus” (1:1). The term signifies the communal life of the people who have been incorporated in Christ (Gorman 2001, 43).

The poetic narrative places before the readers the qualities enjoined in 2:1–4 (Black 1985, 304).

| en Christō (2:1) | en Christō (2:5) |

| in Christ | in Christ |

| to auto phronēte, hen phronountes (2:2) | touto phroneite (2:5) |

| have the same mind, mind one thing | have this mind |

| hēgoumenoi (2:3) | ouch harpagmon hēgēsato (2:6) |

| consider | consider a thing to be grasped |

| kenodoxian (2:3) | heauton ekenōsen (2:7) |

| conceit, vainglory | emptied himself |

| tapeinophrosynē (2:3) | etapeinōsen heauton (2:8) |

| humility | humbled himself |

Three strophes describe the stages in the story of Christ. Marked by the alternation between participles and verbs in the first two strophes, the poem describes the downward spiral of the preexistent Christ in two stages. The first stage describes the incarnation (2:6–7):

Being in the form of God,

He did not count equality with God a thing to be exploited

But emptied himself,

Taking the form of a slave,

Becoming in the likeness of a human.

The parallel verbs describe the action, and the participles indicate the change in status from the form of God/equality with God to the form of a slave/human likeness. The parallelism offers valuable insight into the meaning of the terms. Although morphē in most instances refers to the outward appearance or shape (BDAG 659), here the form of God (morphē tou theou) is the equivalent of equality with God (Marshall in Donfried and Marshall 1993, 132). Thus “form of God” actually refers to the divine nature. The parallel with “form of a slave” (2:7) indicates that the term refers not to outer shape or form but to the nature of the existence. That is, in the initial stage, Christ was equal to God. This appears to be the equivalent of “image of God” in the wisdom literature. The phrase “equal to God” establishes the contrast to Hellenistic rulers, who also claimed to be equal to God.

In the first act of the narrative “he emptied himself,” exemplifying the conduct of one who looks to the interests of others (2:4). The parallel phrases “taking the form of a slave” and “becoming in the likeness of a human” highlight the sharp contrast between the divine and human status, indicating the manner of his sacrifice. This is no Hellenistic story of a deity who made an appearance on earth. The “form of a slave” suggests the abject depth of the descent, for slaves were at the bottom of the social hierarchy. While not all slaves endured the same brutalized existence, those who were free considered slavery as “the most shameful and wretched of estates” (Dio Chrysostom, Or. 14.4). The likeness (homoiōma, cf. Rom. 8:3) of humankind, which can mean “similarity” or absolute likeness (BDAG 707), indicates the participation in the total human condition. Thus two main verbs describe the extent of the descent. Unlike Hellenistic rulers, who exploited their prerogatives, “he did not count equality with God a thing to be exploited.” The absolute humanity of the preexistent Christ is also evident in the phrase “he emptied himself.”

The second strophe has the same alternation of participles and main verbs, indicating the movement from one status to another (2:7–8):

He humbled himself to death,

Even death on a cross.

The first line of the second strophe, “being found in human form,” builds on the last line of the first strophe, “becoming in the likeness of man,” in a sorites. As in the first strophe, the status provides the setting for the action: “he humbled himself to death,” the second stage in the descent. That “he humbled himself” (etapeinōsen heauton) recalls the encouragement to the readers to adopt humility (tapeinophrosynē) as a way of life (2:3). The added phrase, “even death on a cross,” indicates the absolute nadir of the descent and the epitome of shame (Hellerman 2009, 784; Williams 2002, 133). As Paul indicates in 1 Corinthians, the message of the cross is “foolishness” to the Greeks and a “scandal” to the Jews (1:18, 23). John Chrysostom wrote, “Not every death is similar. Jesus’s death seemed more disgraceful than all the others . . . his was accursed” (Hom. Phil. 8, trans. Allen 2013). As Roman writers indicate, it is the most shameful form of death. According to Cicero (Rab. Perd. 5.16), the word cross should be far removed from the “thoughts, eyes, and ears” of Roman citizens.

In the first two strophes the preexistent Christ is the subject of the action who chooses to empty himself and humble himself. In the third strophe God is the subject, and the crucified one is the object. Therefore (dio) marks the radical break in the downward spiral. The subject is no longer Christ who made decisions to empty himself and humble himself, but God who now exalts him. Because the preexistent Christ emptied and humbled himself, God highly exalted (hyperypsōsen) him in a radical reversal of his status (Kampling 2009, 20–21).

The poetic narrative speaks in superlatives, indicating that God has not only exalted Jesus, but has “highly exalted” (hyperypsōsen) the Christ who “emptied himself.” Hyper, both in the compound word and in the claim that the exalted one is over (hyper) every name, indicates that he is in the highest place, the place of God. In the OT this terminology is used only for God. The psalmist exclaims, “For you, O LORD, are most high [hypsistos] over all the earth; you are exalted [hyperypsōthēs] far above all gods” (Ps. 96:9 LXX [97:9 NRSV]). Thus God has exalted the one who chose not to exploit his status as equal to God.

At the exaltation God also conferred the name that is above every other name. Echarisato recalls God’s many acts of grace (charis). This acclamation also occurs in Heb. 1:4, which describes the descent of the preexistent Christ and the exaltation, when he received a “more excellent name” than the angels.

In the OT the name that is above every other name is that of God. The conferring of a name presupposes the ancient view that the name is something real, an aspect of the person whom it designates (BDAG 712). The psalmist speaks of God’s “great and awesome name” (99:3; cf. Deut. 28:58). In Neh. 9:5 the people pray, “Blessed be your glorious name, which is exalted above all blessing and praise” (NRSV). According to Midrash on the Psalms 6, God’s name is “above all names.” Thus God gives Jesus the name that he, in his preexistent state, did not try to grasp. Greek-speaking Jews employed the term kyrios as a reverential substitute for the divine name (Bauckham 1998, 131). Jesus is given the divine name because he participates in the divine sovereignty (Bauckham 1998, 131).

The poem appeals to Isa. 45:23 in 2:10b–11a to support the claim. This passage belongs to the larger context of God’s claim in Deutero-Isaiah, “I am God, and there is no other” (45:22). To the prophetic claim that every knee will bow, the poem adds in heaven and on the earth and under the earth. Whereas the original passage (Isa. 45:23) has “every tongue will confess,” the poem has every tongue will confess that Jesus Christ is Lord to the glory of the Father. The kyrios of the OT is now the preexistent Christ who emptied himself of divine prerogatives.

The elevation of Christ above cosmic powers is a theme elsewhere in the NT, often in comments on Ps. 110:1, which declares the victory of God over the enemies. Alluding to Ps. 110:1 (Rom. 8:34), Paul declares that “neither angels nor principalities nor things to come” will separate believers from the love of Christ (Rom. 8:38–39). Reflecting on Ps. 110:1, he declares to the Corinthians that the resurrected Christ “will rule until he puts all enemies under his feet” (1 Cor. 15:25), when he destroys “every ruler and authority and power” (15:24). Similarly, in Ephesians Jesus is at the right hand of God (1:20; cf. Ps. 110:1), “far above all rule and authority and dominion, and every name that is named” (1:21). Only in Philippians do all worship the exalted Christ and call him Lord. In Rev. 5 all creatures worship the lamb.

The narrative of Christ as the one who humbled himself (heauton etapeinōsen) and was then highly exalted conforms to a common theme in the OT that God will exalt those who are humble (tapeinoi) and bring down the mighty. According to Ps. 74:8 LXX (75:7 Eng.), God exalts (hypsoi) the humble (tapeinoi). God grants favor to the tapeinoi (Prov. 3:34), gives justice to the tapeinoi (Ps. 81:3 LXX [82:3 Eng.]), and delivers the tapeinoi (Ps. 17:28 LXX [18:27 Eng.]). The three young men in the fiery furnace describe themselves and their people as the tapeinoi (Dan. 3:37 LXX), whom God will rescue. The suffering servant is the ultimate example of the triumph of the humble. The servant was taken away “by oppression [en tē tapeinōsei] and judgment” (Isa. 53:8), and he “poured himself out to death” (Isa. 53:12). Nevertheless, he will prosper “and be lifted up [hypsōthēsetai], and shall be very high” (52:13). As a result, all nations will recognize God’s sovereignty (Isa. 52:15) and see the salvation of God (Isa. 52:10; cf. 40:5; 45:22; 49:6).

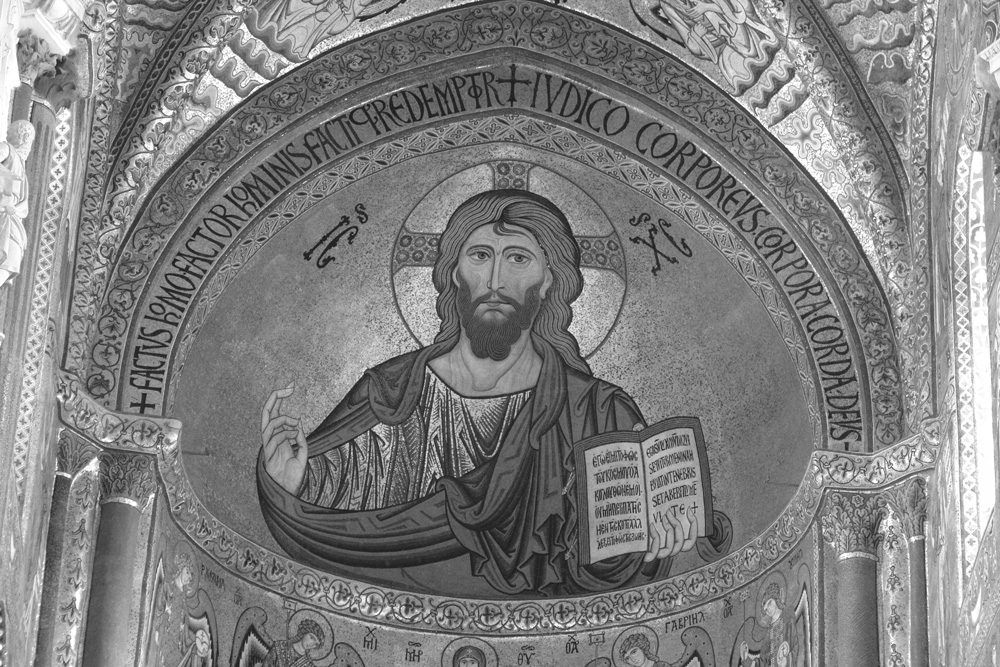

Figure 7. Artist’s depiction of Christ as Pantocrator, the one who rules over all [Andreas Wahra/Wikimedia Commons]

The poetic narrative has a pastoral and paraenetic significance for the readers, for it indicates a reversal of the situation in which they now live (Williams 2002, 146). In a letter that consistently argues from positive and negative examples (1:12–26; 2:19–30; 3:2–21; 4:10–20), Christ is the ultimate example. Those who, like Paul, risk death will be vindicated. As believers worship the one who died a humiliating death, they acknowledge a deity who stands in sharp contrast to ancient rulers, and they take on the values of the one who looked to the interests of others. What the church now confesses will ultimately be recognized throughout the world.

The political significance of this claim would have been apparent to the ancient readers. To the church in Philippi, the passage indicates the cosmic victory described in Deutero-Isaiah. The community that is marginalized by the Roman populace now participates in the humiliation of Christ, but will ultimately be the victors. This claim is a challenge to Roman power.

Theological Issues

The presence of the poetic narrative of 2:6–11 within a sequence of imperatives (2:2, 5, 12, 14, 18) indicates that conduct worthy of the gospel (1:27) cannot be reduced to a series of rules but is inseparable from the community’s defining narrative. The Philippian society, like other societies, had its own narrative that unified the people under Roman rule, gave the citizens an identity, and provided the foundation for moral obligations. Paul recalls a narrative that may be already known to the believers, convinced that behavior “worthy of the gospel” will be radically different from that of the Roman citizens of Philippi. Countercultural behavior requires an alternative narrative.

Throughout Scripture, narrative is inseparable from moral obligation. Israelites recited their story (cf. Deut. 26:5–11) as they recalled their covenantal obligations. The gospels challenge reigning narratives and invite the hearers to participate in the story of Jesus. While Paul does not write a gospel, he consistently appeals to the founding narrative that is the basis for the identity of his communities (e.g., 1 Cor. 15:1–3; 2 Cor. 5:14–15). The founding story is the basis for a new creation—a new way of knowing (cf. 2 Cor. 5:17). According to Phil. 2:5, it is the basis for a new phronēsis—a new mind-set and new habits.

Narrative is also the basis for further theological reflection. Philippians 2:6–11 has stood at the center of theological debates since ancient times. Interpreters have debated the relationship between “being in the form of God” (2:6) and “he emptied himself” (2:7), seeking to determine the extent of the divine self-emptying (kenōsis). The church fathers insisted on maintaining both the humanity and deity of Christ. The one who emptied himself did not cease to be divine. In challenging the Arians, who claimed that the Son was a created being, John Chrysostom declared that “Christ took on what he wasn’t and, when he became flesh, remained God the Word” (Hom. Phil. 8, trans. Allen 2013). The church fathers found a resolution to the mystery in its declaration at the Council of Chalcedon (451 CE) that Jesus Christ is “truly God, truly human, two natures united into one person, without confusion, change, or separation.”

It is not Paul’s purpose to answer the multiple christological questions that subsequent generations have raised but to offer a revolutionary view of God and a new phronēsis—a new way of thinking and acting. “Against the age-old attempts to make God in their (arrogant, self-glorifying) image, Calvary reveals the truth about what it meant to be God” (Wright 1991, 84). In the incarnation, the self-emptying of Christ, both in his human existence and his shameful death, was the ultimate expression of God. Over against the rapacious and self-seeking gods of antiquity, Paul describes a deity who does what we think God is unwilling to do or incapable of doing (Migliore 2014, 85). Thus Paul challenges the imperial claims of the Caesar, confronting believers with a decision: “Do not live as Augustus and the rulers before and after him do. Do not orient yourself to the Caesar and his veterans, but to the Messiah Jesus” (Hecking 2009, 30).

Ernst Käsemann, who lived through the Nazi horrors, said, “One cannot say, as in Nazi times, that one believes in God. It is necessary to be precise who God is” (2010, 175). In shaping the communal consciousness of the Philippians, Paul depicts one who was “equal to God” but, unlike the deities of ancient culture, did not exploit divine prerogatives. Those who worship this deity reject the quest for status and look to the interests of others as their theology shapes their ethics.