Philippians 3:1–4:1

The Example of Paul

Introductory Matters

Since the seventeenth century (cf. Gnilka 1968, 6), interpreters have noted the radical break in the argument that begins with “beware of the dogs, beware of the evil doers, beware of those who mutilate the flesh” (3:2) and concludes with the warning about the “enemies of the cross of Christ” whose “god is the belly” (3:18–19). Indeed, an inclusio provides the frame of the chapter, consisting of (a) a warning against false teachers (3:2, 18–19), (b) a contrast to the church (“we” in 3:3; “our citizenship” in 3:20–21), and (c) Paul’s autobiographical reflection (3:4–17). Thus 3:2–21 is a rhetorical unit that introduces these dangers for the first time.

Since 3:2–21 is a rhetorical unit, interpreters face the additional question of the place of 3:1 and 4:1 in the argument. Most translations render to loipon as “finally” (3:1), suggesting that Paul has reached the conclusion of the letter. As the paragraphing in English translations indicates, the relationship between 3:1a (“rejoice in the Lord”) and 3:1b (“to write the same things is not troublesome to me, and for you it is in your best interests”) is unclear. Thus the questions emerge: Why does Paul speak of writing “the same things”? Is 3:1a the conclusion of 2:19–30 or the beginning of the next section? Where does the new paragraph begin? At the end of 2:30? At the end of 3:1a? Or at the end of 3:1b? Is 3:1b the introduction of the rhetorical unit 3:2–21? The uncertainty over 3:1 has played a role in the issues that have dominated the interpretation of Phil. 3.

Because of the change of tone and subject matter in 3:2, many scholars have concluded that 3:2–21 is not consistent with the remainder of the letter and is thus a fragment of another letter. They have debated two related issues regarding chapter 3: the integrity of the letter and the identity of the opposition.

Philippians 3 and the Integrity of the Letter

J. Gnilka (1968, 8–10) maintains the following reasons for assigning 3:2–21 to a separate letter.

- Paul confronts a changed situation in chapter 3. Whereas he refers to his imprisonment in chapters 1 and 2, he is no longer in bonds in chapter 3. While chapters 1 and 2 are an appeal to unity, chapter 3 is a polemic against opposition not mentioned in the first two chapters. While chapter 1 mentions those who preach from envy and selfish ambition (1:15–17), in chapter 3 Paul warns against false teachers—“the dogs, evil workers, and the mutilation” (3:2)—and those who are “enemies of the cross” and “whose god is the belly” (3:19). Those who are the objects of Paul’s invective in chapter 3 cannot be identified with those who preach Christ with improper motives (1:15–18).

- Closely related to the change of situation suggested by Gnilka is the change of tone in 3:2–21. In contrast to the warm expressions of affection in the first two chapters (1:7–8, 25–26; 2:16), chapter 3 is filled with invective (3:2, 18–19) and polemic.

- Chapter 2 ends with Paul’s travel plans (2:19–30), the encouragement to rejoice (3:1), and the word “finally” (to loipon, 3:1). Travel plans are common near the conclusion of Paul’s letters (cf. Rom. 15:22–33; 1 Cor. 16:5–12; 2 Cor. 12:14–13:10). “Finally” (to loipon) and the encouragement to rejoice appear at the end of 2 Corinthians (13:11), and the exhortation to rejoice appears at the end of 1 Thessalonians (5:16). The fact that it appears again in Phil. 4:8 has convinced many interpreters that Phil. 3:2–4:1 is a separate letter.

Because of an apparent break in the argument in chapter 3, interpreters have offered numerous theories about the redactional history of the letter, maintaining that it is a composite of either two or three letters. A widely held view is that a separate letter begins in 3:1b in which Paul engages in polemic for the first time. Gnilka (1968) distinguishes between letters a (1:1–3:1) and b (the polemic, 3:1b–4:1, 8–9), arguing that Philippians consists of two letters. Others (e.g., Reumann 2008, 15; Bormann 1995, 118) argue for three separate letters, maintaining that 4:10–20 is a thank-you note sent prior to the other sections. Advocates of this view maintain that a thank-you note at the end of the letter appears as an afterthought and that such a delay in expressing gratitude would be inconceivable (see introduction to part 5 and comments on 4:10–20).

Despite the apparent break in the flow of thought at 3:2, arguments for regarding chapter 3 as a separate correspondence are not compelling. Little evidence exists for Gnilka’s claim of a changed situation in the chapter. While the beginning and end of the chapter contain warnings and invective, the remainder of the chapter is autobiographical rather than polemical. The presence of “finally” (to loipon, 3:1), travel plans (2:19–30), and the encouragement to rejoice (3:1) do not always come at the end of a letter but may appear elsewhere in Paul’s letters (Watson 2003, 167–68). “Finally” (loipon) appears in 1 Thess. 4:1 to introduce a new section of the letter, and travel plans appear in 1 Cor. 4:14–21. The word can either be a closing formula or a transitional particle (Garland 1985, 149). To loipon appears frequently in ancient family letters to introduce a new topic (Alexander 1989, 96). As Philippians indicates, “rejoice” (chairete) can appear throughout the letter (2:18, 28; cf. Rom. 12:12, 15).

The case for regarding 3:2–21 as a separate letter is further weakened by the fact that those who maintain this theory do not agree on where the interpolation begins or ends (Garland 1985, 154). Some propose that it begins in 3:1a, others 3:1b, and others with 3:2. This lack of consensus undermines any idea that chapter 3 is an interpolation.

The numerous links between chapter 3 and the first two chapters indicate that chapter 3 fits the flow of the argument and is not a foreign body (see Wojkowiak 2012, 176).

| Philippians 2 | Philippians 3 |

| doxa (glory, 2:11) | doxa (3:19, 21) |

| epigeios (earthly, 2:10) | epigeia (3:19) |

| epouranios (heavenly, 2:10) | en ouranois (3:20) |

| heuretheis (be found, 2:7) | heurethō (3:9) |

| hēgeisthai (regard, 2:3, 6, 25) | hēgeisthai (3:7, 8 [2×]) |

| thanatos (death, 2:8) | thanatos (3:10) |

| kyrios Iēsou Christos (Lord Jesus Christ, 2:11) | Christou Iēsou tou kyriou mou (of Christ Jesus my Lord, 3:8) |

| lambanein (take, 2:7) | katalambanein (obtain, make one’s own, 3:12, 13) |

| morphē (form, 2:6, 7) | symmorphizomenos (be conformed, 3:10) |

| stauros (cross, 2:8) | suffering, death (3:11), enemies of the cross (3:18) |

| schēma (form, 2:7) | metaschēmatizein (transform, 3:21) |

| tapeinoun (to humble, 2:8) | tapeinōsis (humiliation, 3:21) |

| phroneite (have this mind, 2:5) | phroneite (3:15), ta epigeia phronountes (having a mind on earthly things, 3:19) |

These parallels indicate the close relationship between chapters 2 and 3 and the strategic place of chapter 3 in the argument of the letter. This relationship is also evident in the inclusio between politeuesthe (lit. “live out your citizenship,” 1:27) and the politeuma (“citizenship”) in heaven (3:20). It is especially present in the rhythmic conclusion of chapter 3, which Lohmeyer designated as a hymn (see comments on 3:20–21 below). What is noteworthy is the way in which 3:20–21 echoes the hymn in 2:6–11. The one who was in the form (morphē, 2:6) of God was found in human form (schēma, 2:7) at the incarnation and “humbled himself” (etapeinōsen heauton, 2:8). According to 3:20–21, the Lord will transform (metaschēmatisei) the body of our humiliation (tapeinōsis) so that it will be conformed (symmorphon) to the body of his glory. Thus believers follow the path of the Lord from humiliation to transformation into the body of glory. These terms are rare in the Pauline corpus, but link chapters 2 and 3 (Garland 1985, 158).

The Identity of the Opponents

Closely related to the issue of the place of chapter 3 in the letter is the question of the identity of the opponents, which has been a major focus of attention, especially for those who regard chapter 3 as a part of a separate letter. The harsh words of 3:2, 18–19 are reminiscent of the polemic in Galatians and 2 Corinthians. At the beginning of the chapter, Paul warns against the “dogs, evil workers, and mutilation” (3:2), who comprise one group. Because of the paronomasia katatomē—peritomē (“mutilation”—“circumcision”), which offers the most identifiable epithet among the three, interpreters have concluded that Paul engages in polemic against those who demand circumcision. At the end of the chapter, he warns against the “many” who are “enemies of the cross of Christ” (3:18) and “whose god is the belly” (3:19).

Paul’s statement in 3:12, “I have not been made perfect” (teteleiōmai, NRSV “reached the goal”) and the later comment, “Let as many as are ‘perfect’ [teleios, NRSV “mature”] be of the same mind” (3:15) has suggested to many interpreters (e.g., Schmithals 1957, 315) that the apostle is using the terminology of opponents who claim to have reached perfection. Thus, by mirror reading they conclude that Paul is responding to the opponents’ claim to perfection.

These scattered statements have resulted in a variety of attempts to synthesize the evidence of chapter 3 and identify the opponents. Because of the differences in the references to the heretics in 3:2, 18–19, some have suggested that Paul is fighting on two fronts—against Judaizers (3:2) and against libertines (3:18–19). H. Koester (IDBSup 666) and others have synthesized the warnings in 3:2, 18–19 and the references to perfection (3:15) and concluded that Paul confronts a single group, Jewish Gnostics who insist on circumcision as a path to perfection and discount the significance of the cross.

This variety of interpretations reflects the lack of evidence about the opponents, whose views Paul describes only with invective and polemical characterization. Scholars have employed extended mirror reading and the evidence from the polemic in 1 and 2 Corinthians and Galatians to identify the opponents in Philippians, offering a depiction of views for which there is no evidence elsewhere (i.e., Jewish Christian Gnostics). In contrast to the other letters, however, Paul does not engage in extended argument against opponents. Indeed, apart from 3:2, 18–19, Phil. 3 is an extended autobiography.

The brief warning in 3:2, “beware the dogs, beware the evil workers, beware the mutilation,” offers little indication of the identity of the opponents. Although blepete can be rendered “observe” (cf. Stowers 1991, 116), the NRSV’s rendering “Beware” is correct, for Paul is pointing to the danger of the heretics. The threefold blepete (“beware”) has a rhetorical effect. The danger comes from “the dogs, the evil workers, and the mutilation”—invectives that shed little light on the identity of the opposition. Dog is a common invective in antiquity as an image for aggressiveness, threat (cf. Pss. 21:17, 21 LXX [22:16, 20 Eng.]; 58:7, 15 LXX [59:6, 14 Eng.]), and an unquenchable appetite (Isa. 56:10–11). Wild dogs scavenge and eat human flesh (1 Kings 14:11; 16:4; 21:23–24; 2 Kings 9:10; Job 30:1; Jer. 15:3). Thus the epithet draws sharp lines between insiders and outsiders (cf. Matt. 7:6; Mark 7:27–28) and is a vivid image for one’s opponents. The connection with the “mutilation” (katatomē) suggests that Paul has taken a common invective, used widely in polemic (cf. Nanos 2009, 476), to describe one’s opponents. It is used for the Canaanite woman in her encounter with Jesus (Matt. 15:26). While Paul applies it to those who insist on circumcision (Schinkel 2007, 79), the term provides no insight into the identity of the opponents.

The description of the opponents as evil workers (kakous ergatas) also gives no indication of their beliefs. The closest parallel is the reference to the “false apostles, deceitful workers” (ergatai dolioi) in 2 Cor. 11:13. This belongs among Paul’s common epithets for opponents, but gives no clear indication of their teachings.

The reference to the mutilation (katatomē) is the clearest indication of the identity of the opposition. Paul undoubtedly is making a wordplay, describing circumcision (peritomē) as mutilation (katatomē), equating those who insist on circumcision with those who engage in the pagan practice of self-laceration (cf. 1 Kings 18:28). The specific warning against those who insist on circumcision suggests that Paul has inverted the disparaging reference to dogs to refer to the very people who had used that designation on others. Undoubtedly Paul faces those who insist on circumcision, not only in Galatia, but in many places. Thus the issue is probably a potential problem rather than a present reality in the church at Philippi.

The warning in 3:2 is parallel to the warning in 3:18–19, even if Paul characterizes the threat in different terms. In the latter instance, the opponents are “enemies of the cross of Christ” (3:18), “whose god is the belly” (3:19). Once more, Paul refers to opponents in general terms with harsh language, but gives little indication of their beliefs. The statement “as I have often told you of them” (3:18) suggests that Paul’s original catechetical work warned of persistent dangers in Philippi. His warning “with tears” (3:18) indicates the urgency of the situation, which is probably occasioned by the hostile climate in which they live.

The cross stands at the center of Paul’s proclamation. The nadir of Jesus’s descent in the hymn in Philippians is his death on the cross (Phil. 2:8). According to 1 Corinthians, Paul summarizes his preaching as “the word of the cross” (1:18) or “Christ and him crucified” (2:2), a message that is a “scandal” to others (1 Cor. 1:23; Gal. 5:11), for Jews seek signs and Greeks seek wisdom (1 Cor. 1:22). He maintains that those who are involved in partisan rivalry do not understand the message of the cross (1 Cor. 1:10–2:17), and he accuses the opposition in Galatians of making the death of Christ superfluous (Gal. 2:15–21). Thus the “enemies of the cross of Christ” are probably all who do not share Paul’s understanding of the centrality of the cross. “Enemies of the cross of Christ” may refer to the majority culture in Philippi, who shared the common revulsion at the subject of the cross. Because of the repugnance of the cross to the citizens of Philippi, the constant temptation for members was to avoid the message of the cross and their participation in it.

The statement that their “god is the belly” is probably a standard polemic. Belly (koilia) is frequently used metaphorically for the seat of the desires (BDAG 550). Paul concludes his Epistle to the Romans, warning against those who cause divisions (16:18), indicating that “such people serve not the Lord Jesus Christ, but their own appetites” (koilia). He probably quotes a Corinthian slogan when he says, “Food is for the belly, and the belly for food” (1 Cor. 6:13). Thus the belly in Phil. 3:19 is probably metonymy for the life-orientation toward the flesh (cf. 3:3), which is focused on earthly things (3:19; cf. De Vos 1997, 271).

Paul refers to internal opponents nowhere else in the letter. While he refers to those who “proclaim Christ from envy and rivalry” (Phil. 1:15 NRSV), he does not question their message. The opponents whom Paul mentions in 1:28 are outsiders who have the capacity to intimidate the members (1:28) rather than an internal threat. Inasmuch as Paul does not engage in extended polemic in Phil. 3, as in Galatians and 2 Corinthians, the false teachers are more a potential threat than an actual reality. Undoubtedly Paul’s ministry has been plagued by rivals who have insisted on the necessity of circumcision for entrance into the people of God, but the absence of polemic in Philippians suggests that false teaching is not the central concern (cf. deSilva 1994, 30). Morna Hooker is correct to speak of the “phantom opponents” of Philippians (2002, 377–95).

As the sharp contrast between the community and the opponents suggests (3:2–3, 17–21), the opponents serve as rhetorical foils for Paul’s larger purpose. Paul uses the opponents as a negative example to provide a contrast to the appropriate response (Schinkel 2007, 77). Stowers shows that “the fundamental architecture of the book is one of contrasting models” (Stowers 1991, 115). In 1:15–18 he contrasts those who preach Christ from envy and rivalry to those who preach from love. He contrasts those who seek their own interests to Timothy, who is concerned for the welfare of others (2:20–21). Such a contrast establishes collective identity and creates boundaries. David deSilva (1994, 30) has observed that a sectarian group needs confirmation of its identity in order to maintain group cohesion and group boundaries. A reference to enemies strengthens the commitment to the community. Thus in chapter 3 the “phantom opponents” provide the rhetorical foil to create a sharp contrast to Paul’s autobiography. Despite the apparent differences in the description of the opponents in 3:2, 18–19, they have in common that they represent the values of the dominant culture. They place their confidence in the flesh (3:3) and their minds are on earthly things (3:19). Paul’s autobiography, like the Christ hymn in 2:6–11, presents a mind-set that stands in contrast to that of the larger society (Wojtkowiak 2012, 175).

The Rhetorical Purpose of Paul’s Autobiographical Writing

Interpreters who have argued that Phil. 3 is a foreign body in the letter have not recognized the rhetorical purpose of the chapter. This passage is one of several autobiographical sections in the Pauline letters, each of which serves a rhetorical purpose. Second Corinthians, Paul’s most autobiographical letter, is a defense against rivals and a response to charges against him (see 10:1–11; 11:7–11). In 1 Thessalonians the autobiographical section (2:1–12) demonstrates Paul’s character and lays the foundation for Paul’s ethical advice in chapters 4 and 5. Beverly Gaventa (1986, 319–20) has shown that the autobiography in Galatians 1:10–2:21 presents Paul as a model for others. Thus autobiographical sections in Paul can serve either as a defense against attacks or as an example for imitation. As Paul indicates in Phil. 3:17, his task in this chapter is to present himself as an example to the readers. Indeed, his personal example plays a major role throughout the letter. In 1:12–26 he offers his example to those who are anxious about his fate, and in 4:10–20 he is an example of one who can trust God in all circumstances.

The focal point of the chapter is not the opponents but Paul as an example (3:17). The opponents provide the contrasting backdrop for Paul’s presentation of himself. After offering Timothy and Epaphroditus as examples of looking to the interests of others, Paul has followed the path of Christ in abandoning his high status and participating in the sufferings of Christ. Paul demonstrates that his own life embodies the abandonment of selfish ambition, as in the Christ hymn. He gave up his privileges and conformed himself to the cross of Christ.

The argument from the speaker’s character (ēthos) was one of the three proofs suggested by Aristotle (Rhet. 1356a), who said that “it is more fitting that a virtuous man show himself good than that his speech be painfully exact” (Rhet. 1418b; 3.12.13). According to Aristotle, “the orator persuades by moral character when his speech is delivered in such a manner as to render him worthy of confidence; for we feel confidence in a greater degree and more readily in persons of worth in regard to everything in general” (Rhet. 1.2.4, trans. J. H. Freese, LCL; cf. Quintilian, Inst. or. 4.1.7–10). Paul embodies the mind of Christ, which he commends to the Philippians. The argument from ethos was recognized among the rhetoricians as a compelling argument.

The customary autobiographical topics include the speaker’s (1) immediate and remote ancestry, native city or country (genos), and noteworthy facts about their birth; (2) upbringing, education, and choices revealing their character; (3) presentation of the person’s deeds (praxeis) that illustrate moral character; and (4) comparison with other exemplary persons, usually with an appeal for imitation (Lyons 1985, 28). In The Life, Josephus traces his genealogy through five generations of eminent priests on his father’s side (1–6), recalls his upbringing and education (7–12), claims to have investigated the various sects, and even reports a time with the Jewish ascetic Bannus (Lyons 1985, 47). Similar topics are present in 2 Corinthians (11:22–25), Galatians (1:10–24), and Phil. 3:3–6.

Autobiographical reflection also had a major place in philosophical literature, much of which was devoted to the topic of moral formation (Gaventa 1986, 324). Seneca’s Epistulae morales offers abundant evidence of the importance of imitation in moral development. Seneca insists that learning occurs by example, precept (Ep. 7.6–9; 11.9–10), and exercise (Ep. 16.1–2; 78.16; cf. Auct. Her. 1.2.3). On numerous occasions he describes his own struggle to live the virtuous life (Ep. 1.4–5; 2.4–5; 6.1–6; 54.1–6) in order to provide an example for his friend (see Cancik 1967, 75). He describes moral progress toward the goal and concedes that he has not arrived (Ep. 6.1; 87.5). One who is “short of perfection” (imperfecta, 72.1) must “press on and persevere” (instemus itaque et perseveremus; 71.35). Seneca consistently urges his friend to pursue the goal with all of his strength, often speaking with images from athletics. He is delighted that his pupil is in the race (Ep. 34.2), and he urges his friend, “Strive toward a sound mind at top speed with your whole strength” (Ep. 17.1; cf. 78.16). Moral philosophers strengthened their examples by pointing to negative examples of conduct. Seneca warns his friend “not to act after the fashion of those who desire to be conspicuous rather than to improve” (Ep. 5.1).

Unlike Galatians and 2 Corinthians, the chapter is not a polemic but an autobiographical summary used for rhetorical purposes. Employing the antithesis that is familiar in the letter (1:15–18; 2:21), Paul uses the opponents as a foil to highlight his own example. Paul’s autobiography has points of contact with his autobiographical report in 2 Cor. 11:16–32 and Gal. 1:10–2:14. As in 2 Corinthians (11:22), he declares that he is an Israelite and a Hebrew (3:5). He describes his advancement in Judaism, including his zeal, in both Philippians (3:6) and Galatians (1:14). The autobiography in Philippians is distinctive, however. In 2 Corinthians his autobiography has an apologetic purpose, while in Philippians Paul presents himself as a model (see 3:17), describing both his past (3:4–11) and his anticipated future (3:12–21). Like his readers, he now lives between the past, when he made a radical change (3:4–11), and the anticipated future (3:12–21).

Philippians 3:3–6 has some of the common characteristics of the ancient autobiography. Of the seven personal claims, the first four describe Paul’s status from infancy, while the last three describe his own achievements. This distinction corresponds to the categories of ascribed honor and acquired honor (Hellerman 2005, 124) that were common in antiquity. The former includes honors conferred at birth, while the latter describes achievements.

Among Pauline autobiographical claims, only in 3:5 does Paul mention circumcision and his people (genos); he mentions his tribe (phylē) elsewhere only in Rom. 11:1. His claim that he was “circumcised on the eighth day” refers to the badge of identity for Jews, especially in the period of the second temple, but for Paul it was also the topic for boasting (cf. 3:2–3; Rom. 4:1–2). This claim was analogous to ancient references to the circumstances of one’s birth. The claim to be of the “people [genos] of Israel,” which he also makes in other instances (see Rom. 9:4; 11:1; 2 Cor. 11:22), is parallel to ancient authors’ pride in their genos (Lyons 1985, 28; cf. Josephus, Life 1.1; 2.2). The claim that he was from “the tribe of Benjamin” and a “Hebrew of Hebrews” is also an appeal to his ancestry, a frequent theme in ancient encomia. A common feature of ancient inscriptions is the identification of the individual’s tribe (Hellerman 2005, 114). Like his namesake Saul, the first king of Israel, he was from “the tribe of Benjamin,” named for one of Jacob’s favorite sons. To be from the tribe of Benjamin, whose ancestor was the son of Jacob’s favorite wife, was a special honor. Benjamin was the only one of the sons of Jacob born in the land of promise (Gen. 35:16–18). A “Hebrew of Hebrews” was apparently a special claim (cf. 2 Cor. 11:22), probably indicating that he had not assimilated to Greek culture.

Paul proceeds from his status from birth to his own achievements, further indicating his advancement in the Jewish tradition. In ascending order of significance, he lists his achievements. As a Pharisee, he belonged to the school of thought that attempted to preserve the identity of the Jewish people by applying the purity laws to all of Israel. Not only was Paul a Pharisee, but he apparently belonged to the wing that identified itself with zeal for the law and attempted to force it upon others (cf. Gal. 1:14). Those who had zeal for the law looked back to Phinehas, whose zeal led him to enforce God’s commands (Num. 25:11) by executing those who had engaged in idolatrous practices. During times when Israel was threatened, devout Jews appealed to zeal for the law as a motivation for action. The aged Mattathias urged the people, “Let everyone who is zealous for the law and supports the covenant come out with me!” (1 Macc. 2:27 NRSV). Paul reaches the climax of his boasting in the flesh, claiming that he was “blameless” (amemptos, 3:6), a term used frequently in the OT for those who are fully obedient to God (e.g., Gen. 17:1; Job 1:1, 8; 2:3; 4:17; 11:4; 15:14; 22:3, 19; 33:9; Wis. 10:5, 15).

Although Paul lists achievements that were recognized in Judaism, his list would have resonated with a Roman audience, where the display of one’s honors was commonplace. Indeed, Romans included achievements by birth alongside acquired achievements (Hellerman 2005, 123). While the details of Paul’s list of achievements would have been unfamiliar to a Roman audience, the style would have been familiar. “The order in which Paul presents his Jewish status corresponds precisely to the typical structure of honor inscriptions found in the colony. In Phil. 3:5, as in the honor inscriptions, ascribed honor precedes acquired honor” (Hellerman 2005, 125). The elite class in Philippi present their birth status before they present their achievements. Thus Paul does not present an argument against the dogs, evil workers, and mutilators but presents an example of “confidence in the flesh” (3:4) and the quest for honor. Thus “confidence in the flesh” is not only a reference to circumcision, but to all human achievements that function as a basis for status. The comment “if anyone else has a reason for confidence in the flesh, I have more” is reminiscent of Paul’s decision to engage in foolish boasting (2 Cor. 11:16–12:10) in response to others who boasted of their achievements. In both instances, Paul is apparently engaged in synkrisis on the grounds for boasting (S. Ryan 2012, 76). While those who insist on circumcision are only a potential threat, the boasting in one’s achievements is pervasive in Philippi and a consistent threat to community cohesiveness.

Philippians 3, therefore, is not a polemic against a heresy but a rhetorical exemplum that Paul uses as a model for the Philippians to follow (Smit 2014, 353). His focus on his past achievements, the athletic imagery, and his current striving correspond to the way in which moral philosophers encouraged their students to imitate them. The reference to counterexamples in Phil. 3:2, 18–19 is also a common rhetorical device.

As 3:7–11 indicates, Paul’s conversion marked a radical break in his narrative that would not have resonated with a Roman audience. In saying “whatever gains I had, these I come to regard as loss for the sake of Christ,” he speaks of his conversion, applying commercial terminology of profit (kerdos) and loss (zēmia). The literal sense of zēmia appears in Acts 27:10, 21 for the loss of property incurred in the shipwreck on Paul’s way to Rome. Kerdos (“gain, profit,” BDAG 541) and zēmia (“damage,” “disadvantage,” “loss,” BDAG 428) are commonly used as antonyms, especially in the context of accounting (cf. Plato, Leg. 8.835b). Aristotle, in describing the equality that is necessary in order to maintain justice, suggests that inequality is removed only when those who have a surplus of things lose and those who have a deficit gain. He adds, “The terms ‘loss’ (zēmia) and ‘gain’ (kerdos) in these cases are borrowed from the operations of voluntary exchange. There, to have more than one’s own is called gaining, and to have less than one had at the outset is called losing, as for instance in buying and selling” (Eth. nic. 5.4.1133b). One may compare the comment of Epictetus: “When a vase that is not broken and is still useful is discarded, whoever finds it carries it off and considers it a gain [kerdos hēgēsetai], but with you, everyone will consider it a pure loss [pas zēmia]” (Diatr. 3.26.25). Josephus (Ant. 4.274) speaks of profit and loss when he says, “They consider it immoral to profit from the loss of another.” This accounting metaphor is evident in Jesus’s statement, “What will it profit them to gain [kerdēsē] the whole world and forfeit [zēmiōthē] their life?” (Matt. 16:26).

Figure 9. Artist’s depiction of Paul’s encounter on the road to Damascus [Wikimedia Commons]

In the statement “I have come to regard as loss” (hēgoumai), Paul employs the perfect tense to describe a point in the past that remains the reality in his life. Paul indicates that “not only were the profits wiped out; they became losses” (TLNT 2:159). One may compare the references to his conversion in Gal. 1:13–24 and 2 Cor. 4:5–6.

The imagery of profit and loss also appears in rabbinic literature, where it is applied to the observant Jewish life: one should balance the loss incurred by keeping the commandments by the greater profit that it entails (m. ʾAbot 2.1; cited in Bockmuehl 1998, 205). Thus perhaps the image was known to Paul before his conversion.

In 3:12–16 Paul turns from commercial imagery to the imagery of the runner in pursuit of a goal. The phrase “I press on [diōkō] that I might lay hold of [ei kai katalabō, lit. “if I may grasp”]” (3:12) has no object in Greek; thus it is a generic description of a pursuit, with a special emphasis on the intense effort involved. Diōkō (“I press on,” “I pursue”) can be used either in the negative sense of “persecute” (Matt. 5:10–12; 10:23; 1 Cor. 4:12; 2 Cor. 4:9) or in the positive sense of pursuing a worthy goal (cf. Rom. 12:13; 14:19; 1 Cor. 14:1), with the emphasis on running or chasing after a person or an object (A. Oepke, TDNT 2:230). The word is frequently used with forms of katalambanō (“to make something one’s own, win, attain, grasp,” BDAG 519). Together the two verbs suggest the intensity of the pursuit in order to reach the goal. One may contrast Paul’s statement “I pursue that I might lay hold of” with the contrast between gentiles who did not pursue (diōkonta) righteousness but received (katelaben) it, and the Jews who pursued (diōkōn) the law of righteousness and did not attain it (Rom. 9:30–31). Paul’s singular focus is the opposite of that mentioned in Sir. 11:10, which describes the person who is preoccupied with many matters: “If you pursue [diōkēs], you will not overtake [katalabēs]” (NRSV).

While Paul does not supply an object in 3:12, he introduces an object in 3:13–14, indicating that the pursuit is toward the finish line in a race. Like the runner who does not look back, he aims toward the goal of the prize (brabeion), the victory wreath that was given to the winner. Paul employs similar imagery in 1 Cor. 9:24 to describe the prize (brabeion) that goes to the winner of the race. In both instances, the prize is not the laurel wreath but the resurrection (cf. 3:11).

In 3:20–21 Paul contrasts the majority (3:18) with the believing community, moving from the third-person plural to the first-person plural—from the “many” (polloi) who will be destroyed to the believing community that says, “As for us, our citizenship [politeuma] is in heaven” (3:20). While their end (telos) is destruction, “we wait for a Savior.” The emphatic hēmōn (“our”), placed first in the sentence emphasizes the contrast between the church and the majority population (see comments on 1:27 for further discussion of politeuma among Jews and Romans), which takes pride in its Roman citizenship.

Ernst Lohmeyer notes that 3:20–21 is a carefully crafted sentence in Greek, written in a rhythmic style that stands out from the preceding argument, concluding that it is a pre-Pauline hymn (Lohmeyer 1953, 156–57). The main clause, “our citizenship is in heaven” (3:20a), is followed by two subordinate and parallel clauses (3:20b; 3:21a) introduced by the relative pronoun ex hou (NRSV “from there”) and hos (“who,” NRSV “he”), followed by the claim of divine power (3:21b). Lohmeyer also observed the unusual vocabulary in this statement: politeuma (“citizenship”), en ouranois (lit. “in the heavens”), sōtēr (“savior”), metaschēmatisei (“he will transform”), and sōma tēs tapeinōseōs hēmōn (“body of our humiliation”). This unusual vocabulary, as Lohmeyer notes, has points of contact with the poetic narrative in 2:6–11 (see above). The evidence offered by Lohmeyer is not sufficient, however, to determine that 3:20–21 is a hymn, for it lacks many of the characteristics of a hymn.

The passage confronts us with Paul’s relationship with Roman power, a theme that he introduced in the first two chapters. “Our citizenship [politeuma] is in heaven” has a special significance in Philippi, where Roman citizenship was highly prized. Inscriptions attest the significance of citizenship in Philippi (Schinkel 2007, 103). Over against the high evaluation of citizenship and striving for it in Philippi, Paul points to citizenship in heaven. Believers in Philippi are like colonists in a foreign land (cf. Pilhofer 1995, 127). For this community, Roman citizenship loses its relevance (Wojtkowiak 2012, 209). Believers are obligated, not to Caesar as Lord, but to Jesus Christ as Lord.

To be a citizen is to accept the mores and values that accompany citizenship. Paul suggests that the church and the Philippian society, with its values of competition for honor, are two incompatible states. While Roman society is oriented toward earthly things, the believers are oriented toward their heavenly citizenship with its mores. This passage coordinates with the instruction in 1:27, “Live out your citizenship [politeuesthe] worthily of the gospel.” This contrasts the community with the world, as in 2:14–15, and explains the hostility that the church faces (1:28). The church belongs to a politeuma that surpasses Rome, for it is in heaven.

Whereas Rome looked to Caesar as the one who preserves peace and security, “we await a Savior who comes from heaven” (3:20). Although the verb “to save” (sōzein) is commonplace in the NT, Paul is the first to use the word sōtēr for Jesus Christ. This claim is in direct conflict with the Roman designation for Caesar. The emperor Claudius was frequently referred to as sōtēr. Paul promises that the sōtēr comes from heaven, the state to which the believers belong (ex hou, “from there,” 3:20), to rescue them (Oakes 2001, 139). The imagery suggests the role of the emperor as the military leader of the state who comes to drive out the occupying force. The Philippians could have remembered events two decades earlier when the emperor, represented by his legions, arrived to drive away the Thracians (Oakes 2001, 139). This claim should reassure Philippian believers, who see only the threatening power of Rome (Tellbe 1994, 112).

Tracing the Train of Thought

Rejoice in the Lord (3:1)

3:1. Although Phil. 3 is not, as many scholars have maintained, a separate letter written on a different occasion from the other chapters, it is nevertheless a defined rhetorical unit. However, the boundaries of the passage are not entirely clear. Since to loipon (NRSV finally) does not mark the end of the letter, as in 4:8, it should be rendered “as far as the rest is concerned” (cf. BDAG 602), as it introduces the discussion that follows. Rejoice in the Lord (3:1a), a refrain that marks the transition between topics in Philippians (cf. 2:18; 4:4), and “stand firm in the Lord” (4:1) form the outer frame of this section, a reminder that the community’s entire existence is “in Christ” (1:1; 2:1, 5). Paul offers the basis for these imperatives in 3:2–21.

In both the beginning and the end of this section, Paul speaks in the intimate tones of the family, addressing the readers as my brothers and sisters (3:1, adelphoi mou, lit. “my brothers”) and as “my brothers and sisters, whom I love and long for, my joy and crown” (4:1). The language of the fictive family reflects the relationship that is the basis for the imperatives, especially the call for imitation (3:17). The Philippians are not only Paul’s partners (1:5, 7) but also his “brothers and sisters” and “beloved” (see 1:12; 2:12; 3:1, 13, 17; 4:1, 8). In his care for the church, he also takes a paternal role as the basis for his authority (Still 2012, 63).

Because Paul writes with no conjunctions in 3:1–2, interpreters have debated the relationship between the three sentences, two of which are imperatives. “Rejoice in the Lord” (3:1) is a refrain (cf. 2:18; 4:4) that marks the transition from 2:19–30 to the autobiographical section in 3:2–21. Because of the impending arrival of Timothy, Paul, and Epaphroditus, the Philippians may now rejoice in the Lord (cf. Reed 1996, 82). The relationship between 3:1a (“rejoice in the Lord”) and 3:1b to write the same things is not a matter of hesitation (oknēron, NRSV “troublesome”) for me, and for you is trustworthy (asphalē, NRSV “safeguard”) is unclear (cf. Reed 1996, 77). Jeffrey T. Reed (1996, 77) maintains that the phrase is a hesitation formula, a common literary convention. Similarly, the relationship between 3:1b and the imperative in 3:2 (“beware of the dogs . . .”) is unclear. Some have interpreted the same things (ta auta) as a reference to 3:1a (“rejoice in the Lord”), while others interpret it as a reference to 3:2–21. Paul’s indication that he is repeating himself in 3:1b forms an inclusio with the statement in 3:18 that he had warned the Philippians many times about the dangers. Thus “to write the same things” is probably to repeat what Paul had said on his earlier visit. Much of the content of his previous instruction is probably present in 3:2–21. Thus the warning and exhortation in 3:2–21 are trustworthy (asphales) for the readers.

To rejoice in the Lord (3:1) is to imitate Paul, who rejoices in the context of his imprisonment (1:4, 18; 2:18) and challenges the readers to rejoice with him (2:18). Their rejoicing, like Paul’s, is in the context of the anxieties facing the church in its present situation. Paul invites the readers to recognize, with OT writers, that the faithful rejoice in God as their strength (cf. Neh. 8:10). Mount Zion is the joy of all the earth because God is Israel’s defense (Ps. 48:2–3). As the remainder of chapter 3 suggests, believers rejoice in the Lord when they look beyond the present duress and recall their participation in a heavenly calling (3:14, 20–21).

Paul’s Conversion and Change of Values (3:2–11)

The section 3:2–21 is a carefully structured unit framed by the parallel in 3:2–4 and 3:17–21. This unit contains (a) a warning against opposition (3:2, “beware the dogs, the evil workers, the mutilation”) and against the enemies of the cross of Christ whose god is the belly (3:18–19), (b) the first-person plural identifying the church (3:3, “we are the circumcision”; 3:20, “our citizenship is in heaven”), and (c) Paul’s first-person reference (3:4, “I have reason for confidence in the flesh”; 3:17, “be my imitators”). At the center of the discussion, as 3:4b–16 indicates, is the Pauline autobiography. Thus the opponents function as the foil for the primary focus on Paul, who is a model for the church.

3:2–3. The true circumcision. The opening warning in 3:2 has a strong rhetorical effect. The threefold beware (blepete) heightens the rhetorical impact. The imperative blepete, which can be translated either as “beware” or “observe” is parallel to the imperative “observe” (skopeite) in 3:17. Because Paul is pointing to threatening forces in 3:2, the meaning “beware” is probably intended. Thus at the beginning and end of the chapter, Paul challenges the readers to beware of negative models (3:2) and observe (3:17) those who follow his example.

The rhetorical power of Paul’s warning is also evident in the alliteration with which he names the opposition: the kynas (dogs), the kakous ergatas (evil workers), and the katatomē (those who mutilate). Because the three terms, like the reference in 3:18–19, are more invective than description, one cannot draw a profile of the opposition. Because of Paul’s frequent encounter with those who insist on circumcision, katatomē is evidently a word that he has coined to refer to the peritomē (circumcision). Since the letter lacks any other reference to the demand for circumcision, the gentile church at Philippi is probably not confronted with this immediate danger. For Paul, they are examples of what he describes as confidence in the flesh (3:4).

The emphatic we—not “they”—distinguishes the Philippian church from others (3:3). Paul uses the first-person plural for the first time, identifying himself with the church. We are the circumcision (3:3) and “our commonwealth is in heaven” (3:20) are parallel claims, contrasting the church with the opposition (Schenk 1984, 254). “We are the circumcision” is a statement of the collective identity of the community and an affirmation that this minority group has an honored place and history. It is not those who insist on circumcision (the mutilation) who are the circumcision, but “we,” the community composed of Jews and gentiles, who are. The term indicates that this gentile community not only participates in Israel’s story, but is the culmination of that story.

Paul alludes to the metaphorical use of circumcision that described the renewed Israel after the return from exile. Moses commands Israel, “Circumcise the foreskin of your hearts” (Deut. 10:16). Israel looks forward to the time when “God will circumcise the foreskin of [their] hearts” (Deut. 30:6). In Romans Paul reverses the categories of circumcision and uncircumcision, insisting that a Jew is one inwardly, and real circumcision is a matter of the heart—it is spiritual and not literal (Rom. 2:28). The image continues in Colossians, according to which believers “were circumcised with a spiritual circumcision” (Col. 2:11 NRSV).

Paul elaborates on the identity of the church, using three participial phrases to describe those who are the circumcision. They are the ones worshiping in the Spirit and boasting in the Lord Jesus Christ and having no confidence in the flesh. As people who already possess the fellowship of the Spirit (2:1, NRSV “sharing in the Spirit”), they have received the promised gift for the renewed people of God. Ezekiel spoke of the time when God would place the Spirit within the people (Ezek. 11:19; 36:26–27). Paul’s letters consistently affirm that the Spirit is the divine power that enables believers to do God’s will (Rom. 8:1–11; 1 Cor. 12:1–14:40; Gal. 5:16–25; 1 Thess. 4:8). In describing believers as those who worship (latreuontes) in the Spirit, Paul employs a verb that was commonly used in the OT for cultic observances (cf. Exod. 4:23; Deut. 10:12; Josh. 22:27; 1 Macc. 2:19; cf. Heb. 9:1–6). In Rom. 12:1 all of Christian conduct is “spiritual worship” (latreia). Thus to worship in the Spirit is the equivalent of walking in the Spirit (Gal. 5:16) or being led by the Spirit (Gal. 5:18). The Spirit dwells in the community, God’s temple (1 Cor. 3:16), which responds by worshiping in the Spirit. Thus in sending gifts through Epaphroditus, they have sent a sweet-smelling sacrifice (Phil. 4:18).

From Jeremiah, Paul knows the difference between arrogant boasting and boasting in God. Jeremiah condemned boasting in one’s wisdom, might, or wealth but challenged his listeners to boast in the fact that God is the Lord (9:23–24). Similarly, Paul cautions against boasting about one’s works of the law (cf. Rom. 3:27; 4:2), human leaders (1 Cor. 3:21), or achievements (cf. 2 Cor. 11:12, 16, 18), for all such boasting is “confidence in the flesh” (Phil. 3:4; cf. 2 Cor. 11:18). He probably echoes Jeremiah when he indicates that legitimate boasting is “in the Lord” (1 Cor. 1:31; 2 Cor. 10:17) or “in the cross” (Gal. 6:14). Indeed, because of the saving work of Christ, the community can now boast in hope (Rom. 5:2) and even boast in its sufferings (Rom. 5:3), for boasting is “in God through our Lord Jesus Christ” (Rom. 5:11). Because God is at work, Paul will boast about the Philippian church at the day of Christ (Phil. 2:16; cf. 2 Cor. 1:14; 1 Thess. 2:19). Thus Paul further describes the community as those “boasting in the Lord Jesus Christ” (Phil. 3:3).

Paul emphasizes the exclusive nature of the boast: to boast in Christ Jesus is to deny all other objects of devotion. Thus by identifying the church as those who do not have confidence in the flesh (Phil. 3:3–4), Paul contrasts those who worship in the Spirit and boast in the Lord Jesus Christ with those who have confidence in the flesh. The contrast between worshiping in the Spirit and confidence in the flesh recalls Paul’s frequent contrast between flesh and Spirit, the two contrasting powers. The phrase can refer to those who insist on circumcision (cf. Gal. 3:3) or to those who live without the Spirit of God (cf. Rom. 8:1–11; Gal. 5:16–25). In Phil. 3:3–4 Paul contrasts the confidence in the flesh with the worship in the Spirit. Confidence in the flesh is confidence in one’s own achievements.

3:4–7. Paul’s gains and losses. The identification of the church as those who do not put their confidence in the flesh introduces the transition from the description of the church to Paul, whose autobiographical reflections extend from 3:4–17. Paul is a model for the church (3:17) as he looks back over his radical change of values. He responds, Although I have confidence even in the flesh (3:4, NRSV “have reason for confidence in the flesh”) and adds, If anyone thinks that he has reason to have confidence in the flesh, I have more, introducing the list of achievements in 3:5–6. Paul thus engages in a synkrisis with any who have confidence in the flesh. This synkrisis is parallel to 2 Cor. 11:21, “But whatever anyone dares to boast of . . . I also dare to boast of that,” and the list of achievements that follows. Paul is probably comparing himself to many in the city of Philippi who boast of their achievements.

Paul announces the radical change in values in 3:7 with the image of profit and loss, which he develops in 3:7–11. Although some manuscripts add the conjunction all’ (NRSV “yet”) to provide a transition from Paul’s gains (3:4b–6) to his change of values in 3:7–11, the best early manuscripts omit the conjunction. Paul gives a thesis statement in 3:7 and then elaborates on the profit and loss. Verses 8–11 are one sentence in Greek that describes the radical change in values:

Whatever gains [I had] I have come to regard as loss because of Christ.

Indeed, all things I regard as loss because of the surpassing knowledge of Christ Jesus my Lord,

for whose sake I regarded all things as loss,

and [all things] I regard as rubbish in order that I may gain Christ. (3:7–8)

All of the achievements of 3:5–6 are the gains (kerdē) that Paul now considers loss (zēmia). The use of the perfect tense “I have come to regard” (hēgoumai) points to an event in the past that is a continuing reality. The verb (from hēgeomai) suggests a parallel to the preexistent Christ who did not count (hēgēsato) equality with God a thing to be grasped (2:6), and the transference of gain to loss recalls the self-emptying of Christ (2:7). This radical change of values took place “because of Christ.” As Paul indicates in Gal. 2:19, he “died to the law” in order to “live for God.” While the law continues to be a source of moral instruction (cf. Gal. 5:14; 6:2), Christ is now the source of his righteousness. Although Paul could compare his achievements with those given by the elite citizens of Philippi, he has rejected the values of the dominant society.

3:8–11. Paul’s participation in the sufferings of Christ. In 3:8–11, which is one sentence in Greek, Paul elaborates on his claim, beginning with the emphatic more than that (alla menounge kai), a remarkable sequence of particles that are difficult to translate but that in Greek mark the shift from the perfect tense “I counted” (hēgēmai, 3:7) to the present tense “I count” (hēgoumai, 3:8; Hawthorne 2004, 189). Instead of “whatever gains” (hatina . . . kerdē) that he counted as loss (3:7), Paul counts all things (ta panta) as loss (3:8). The emphasis on “all things” indicates that it is not only the Jewish heritage that he considers a loss but every claim to achievement. He adds the aorist tense I lost all things and concludes with the present tense I count (hēgoumai) all things as rubbish (skybala) in order that I might gain Christ. Skybala can mean either the refuse that is thrown to the dogs or the excrement from the dog. Paul employs the strongest language to describe the inversion of values. This is a radical means of describing Paul’s participation in the story of Christ’s self-emptying. What Paul counts as loss is neither his past in Judaism nor his blameless keeping of the law, but these achievements as examples of confidence in the flesh. Even those things that are highly beneficial lose their value in comparison to Christ (cf. Campbell 2011, 50).

Paul expresses the goal of this new “profit and loss” statement with two verbs: that “I may gain [kerdēsō] Christ” (3:8) and be found (heurethō) in him (3:9). Paul has inverted his old values; what were once in the profit column become losses when he gains Christ. To be “found in him” is parallel to the situation of Jesus, who had emptied himself, “being found” (heuretheis) as a man (2:7). The second clause explains what it means to gain Christ. Paul expresses this goal in a chiastic structure that contrasts two kinds of righteousness (see O’Brien 1991, 394). The ultimate goal will occur at the end-time, but Paul already experiences this transformation (cf. Fee 1995, 320).

my own (emēn)

righteousness (dikaiosynēn)

that comes from the law (ek nomou)

but through faith in Christ (pisteōs Christou)

that comes from God (ek theou)

righteousness

by faith. (3:9)

Paul speaks in the antitheses that are common in Galatians and Romans: his own righteousness in which he was blameless (3:6) and the righteousness by faith (3:9); righteousness from the law and the righteousness of God. He has discovered that the alternative to the righteousness by which he was once blameless (3:6) is the righteousness that comes from faith in Christ (pisteōs Christou), stating succinctly here what he develops in Galatians and Romans, where he frequently speaks in the stark alternatives between law and faith (Gal. 3:12), Christ and the law (Gal. 2:19–20), and one’s own righteousness and the righteousness of God (Rom. 10:1–4). Thus to gain Christ is to count as loss the quest for his own righteousness.

Interpreters debate the meaning of pistis Christou as the alternative to the righteousness based on law. The phrase appears also in Galatians and Romans as the alternative of works of the law (e.g., Rom. 3:22, 26; Gal. 2:16). Most translations render this genitive phrase “faith in Christ” (objective genitive), although the phrase may be also rendered “faithfulness of Christ” (subjective genitive). Indeed, the most common rendering of pistis followed by the genitive of the person refers to the faithfulness of the individual rather than faith in an individual (O’Brien 1991, 398; cf. Rom. 3:3, faithfulness [pistis] of God; 4:16, faithfulness [pistis] of Abraham). However, the numerous times that Paul uses pistis without an object (cf. Rom. 1:5, 8, 12, 17; 3:28–30; 5:1; 2 Cor. 5:7) or speaks of believing in Christ (Rom. 10:10–11; Gal. 2:16) or God (Rom. 4:3, 5) suggest that faith is the human response to God’s grace. The parallel between pistis Christou and pistis in Phil. 3:9 indicates that the alternative to righteousness from the law is faith in Christ, the human response to God’s gift. This faith is not, however, a virtue, but a gift—as Paul has declared already in Philippians (1:28)—that brings great joy (1:25). Thus Paul has made a radical turn from the confidence in the flesh to faith in Christ. Neither in describing his previous gains as loss nor in his abandonment of his own righteousness does he deny the continuing importance of the Torah in his life. What he has counted as loss is the confidence in the flesh. This radical break is a challenge not only to those who boast of achievements under the law but to all who have confidence in the flesh.

Paul elaborates on this new balance sheet in 3:10 with the infinitive phrase to know him (NRSV “I want to know Christ”), which is evidently the equivalent of “the knowledge of Christ” (3:8) that he gained when he counted his achievements as loss. Paul once knew Christ “in a worldly way” (kata sarka, 2 Cor. 5:16), but he has come to know him in a new way. The phrase, expressing purpose, elaborates on Paul’s earlier purpose statement, “in order that I may gain Christ and be found in him . . .” (3:8–9). “To know him,” a phrase that recalls the OT theme of knowing God (cf. Jer. 31:34; Hosea 2:20; Wis. 15:3), is an alternative way of describing faith in Christ (3:9). To know him is not to have a body of information about Christ but to enter into a relationship with him.

The relationship between “to know him” and the power of his resurrection and the sharing of his sufferings (3:10) is unclear. Most translations render the kais (and) as parallel, indicating that “to know” has a threefold object: him (Christ), the power of his resurrection, and the sharing of his sufferings. A more likely reading is to interpret the first kai as epexegetic; that is, the power of his resurrection and the sharing in his sufferings indicate what it means to know him. Thus the appropriate translation is “to know him, that is, the power of his resurrection and the sharing of his sufferings” (Fee 1995, 328).

Paul expresses the meaning of knowing Christ in a chiasm (3:10–11):

A Both the power (dynamin) of his resurrection (anastaseōs)

B And the sharing (koinōnian) of his sufferings (pathēmatōn)

Bʹ Being conformed (symmorphizomenos) to his death

Aʹ If somehow I will attain to the resurrection of the dead.

In contrast to the old existence, to know Christ is to experience God’s power (cf. Rom. 1:16; 15:13; 1 Cor. 1:18, 24; 2:4; 4:19–20; Gal. 3:5). As the juxtaposition of “the power of his resurrection” and “the sharing of his sufferings” indicates, this power is present for those who share in his sufferings, as Paul indicates in the other letters. Believers “suffer with him” and will be glorified with him (Rom. 8:17). The sufferings of Christ overflow in Paul’s life (2 Cor. 1:5), and other believers share in his sufferings for Christ (2 Cor. 1:7). God’s power is present in Paul’s own weakness (2 Cor. 4:7; 12:9) as he carries around the dying of Jesus in his body (2 Cor. 4:10). Paul has already mentioned the suffering of the Philippians (1:29), indicating that they are involved in the same struggle that he faces (1:30). Thus God’s power is especially present in the sharing of the sufferings, which Paul models for his readers.

Parallel to the sharing of his sufferings is “being conformed to [symmorphizomenos, NRSV “becoming like him”] his death.” Just as Jesus, though being in the form (morphē) of God, became obedient to death, to know Christ is to be conformed (symmorphizō) to his death, which is the prelude to being conformed (symmorphon) to the body of his glory (3:21). Paul’s present sufferings, therefore, are not unexpected events that call into question the legitimacy of his ministry but are instead participation in the narrative of Jesus (2:6–11). Indeed, Paul may be anticipating that his imprisonment will result in death. Thus if the Philippians now suffer with Paul (cf. 1:30), they are following in the path of Jesus.

This path leads ultimately to resurrection, as Paul indicates, saying, “if somehow [ei pōs] I might attain [katantēsō] the resurrection from the dead.” “If somehow” expresses not doubt about the outcome of Paul’s sufferings but the reality that being conformed to his death is the necessary prelude to the resurrection. As Paul says in Romans, “If we suffer with him, we shall be glorified with him” (8:17). Katantaō (“attain”) suggests the journey toward a destination (cf. BDAG 523), the resurrection from the dead. Thus Paul stands between the radical break in his life and its ultimate outcome, the resurrection.

From the Present to the Future (3:12–21)

3:12–14. Pressing on to perfection. This journey is incomplete, however, for the final act in the drama awaits him. Although Paul has shared with Jesus the self-emptying of Christ, he remains on the path to the ultimate goal. Anticipating a misunderstanding, he adds, not that (ouch hoti) I received (elabon, NRSV “obtained this”) or have been made perfect (teteleiōmai, NRSV “have reached the goal”), but I press on (diōkō) to make it my own (ei kai katalabō) (3:12). In Greek, neither “received” (elabon) nor “press on” (diōkō) has a direct object, but the referent is apparently the resurrection mentioned in verse 11. To be “made perfect,” therefore, is to reach the ultimate goal, the resurrection, which Paul then describes with the imagery in 3:13–14.

The images suggested by “press on” (diōkō) and “make it my own” (katalambanō) were probably familiar to the ancient audience. Paul was once a “persecutor [diōkōn] of the church” (3:6), but now he claims, “I press on” (diōkō), suggesting the intense effort that he makes in order to reach the goal. Katalambanō (“lay hold of”) is an intensified form of “receive” (lambanō) and means “win,” “catch up with,” or “grasp” (BDAG 520; G. Delling, TDNT 4:9). The two words are frequently used together in Greek literature. Extending the image of grasping, Paul adds the reason for his pursuit: because (eph hō) I have been grasped (katelēmphthēn) by Christ Jesus. That is, Paul hopes to grasp the goal because he has been “grasped” by Christ. He counted all things as loss at his conversion and was also grasped by Christ at that moment.

Paul elaborates on the images of pursuing and reaching the goal in verses 13–14, speaking in intimate terms and addressing the readers once more as siblings (adelphoi, 3:13). The negative statement I do not consider that I have made it my own (kateilēphenai) reiterates the claim that he has not yet been made perfect. Instead, in forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead, he is like a runner. In forgetting what lies behind, he recalls the achievements he mentions in 3:5–6, which he counted as “loss.” In straining forward to what lies ahead, he indicates the intense labor that is involved in the pursuit of the goal, using the image of the runner who exhausts himself.

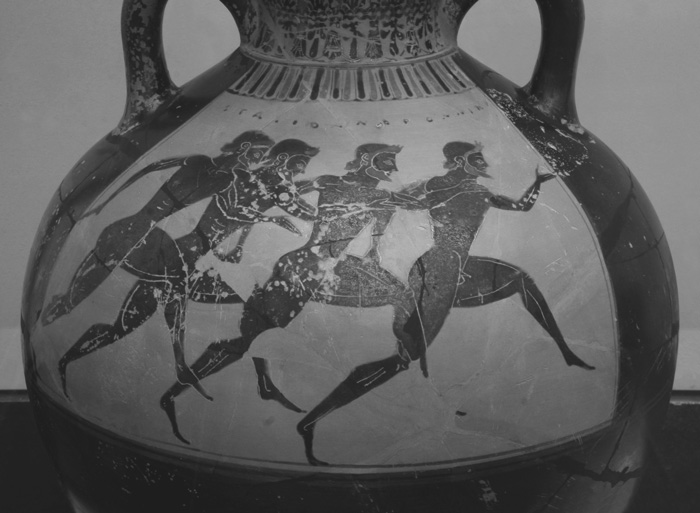

Figure 10. Greek vase depicting runners at the Panathenaic Games, ca. 530 BCE [Wikimedia Commons]

In 3:14 Paul elaborates on the earlier statement (3:12), now explicitly indicating the object of the pursuit. He presses on toward the goal (kata skopon) of the prize (brabeion). Skopos is an image commonly used for the target in archery. In combination with diōkō, it suggests the runner looking at the finish line. Paul uses a similar image in 1 Cor. 9:24 for the prize that the runner wins in the contest. In this instance the prize is the heavenly (anō, lit. “upward”) calling in Christ Jesus. The genitive is probably a genitive of apposition, indicating that the prize is the upward calling. Paul envisions the Christian life as a calling. He has been called to be an apostle (Rom. 1:1; 1 Cor. 1:1), and his converts have also been called into the fellowship of Christ (Rom. 1:6, 7; 8:28; 1 Cor. 1:26; 7:17–24; 1 Thess. 2:12; 4:7). This call is “upward” to the resurrection (3:11), the “perfection” (3:12) that he has not yet received, and the ultimate destiny of those who are conformed to the death of the Son.

For anyone who is disoriented by the present suffering, Paul demonstrates from his own life that the struggle is the prelude to the ultimate triumph. The higher calling indicates that the Philippians who share Paul’s suffering anticipate participation in the glory of Jesus (3:20–21).

3:15–16. Acquiring a new mind-set. Paul turns from autobiography to exhortation in 3:15–21, stating the implications of his autobiography for the readers. This section has a chiastic structure, as Paul proceeds from A (the hortatory appeal in first-person plural, 3:15–16) to B (the negative examples, 3:18–19) and again to Aʹ (the first-person plural, 3:20–21; cf. Willis 2007, 187). As many of us who are mature (teleios, 3:15) forms an inclusio with Paul’s personal claim (3:12), “Not that I have become perfect” (teteleiōmai). The contrast between Paul’s statement that he has not been perfected (NRSV “reached the goal”) and “as many of us who are mature” (teleios) has suggested to numerous scholars that Paul is being ironic in speaking of those who are teleios in 3:15. However, since Paul includes himself, he is probably not using the word in an ironic sense (cf. Bockmuehl 1998, 226), but is using teleioō/teleios in two different ways. The NRSV rendering “mature” is appropriate in 3:15. Teleios is used in the Septuagint for those who wholeheartedly follow God’s ways (cf. Gen. 6:9; 1 Kings 8:61; 11:4). Those “of us who are mature” are the people who recognize, with Paul, that they have not yet reached the goal but are striving to reach it.

The exhortation let us have this mind (NRSV “be of the same mind”) is an appropriate conclusion to the autobiography. Paul introduced the Christ hymn (2:6–11) with the imperative “Have this mind among you” (touto phroneite, 2:5) and concludes his autobiography with the same injunction, “Have this mind” (touto phronōmen), which he contrasts with anyone who thinks differently. Thus in conforming his life to that of Christ, he exemplifies the moral reasoning (phronēsis) that he hopes to instill among the readers. The Roman emphasis on honor and selfish ambition is to be put away, and the mind of Christ is to be adopted.

Paul contrasts those who have the same mind (touto phronōmen) with those who think differently (heterōs phroneite, 3:15b). He is probably envisioning not opponents among those who think differently but believers who differ on anything that remains unresolved (cf. O’Brien 1991, 438). He assures them that God will reveal (apokalypsei) to the readers where their thinking has gone wrong, but he does not say when this occasion will take place. Both the verb apokalypsei and the noun apokalypsis refer to divine communication that occurs in the gospel (see Rom. 1:17; 1 Cor. 2:10; Gal. 1:12, 16), in prophetic disclosures or ecstatic visions (see 1 Cor. 14:6, 26, 30; 2 Cor. 12:1, 7; Gal. 2:2), and at the eschaton (Bockmuehl 1998, 227). Paul probably envisions the continuing revelation in the community, as in 1 Cor. 14:6–30.

Having indicated that we have not reached the destination, Paul concludes the image of the runner pursuing the goal, encouraging the Philippians, let us hold fast (stoichein) to what we have attained (ephthasamen). Thus while we have not reached the resurrection (3:11) or the prize (3:14), we have reached a stage along the way. One may compare Paul’s statement that Israel, while pursuing (diōkōn) righteousness by the law, did not attain (ephthasen) it (Rom. 9:31). The opposite is the case, according to Phil. 3:16. Believers have attained the righteousness of faith (cf. Phil. 3:9), and the task of the community is to hold fast (stoichein) to it. Stoichein, which has the literal meaning of “be in line with a person or thing considered to be a model of conduct” (BDAG 946), is a term that can mean “to follow in someone’s footsteps” (Rom. 4:12) or conform to a rule (Gal. 6:16). This exhortation is parallel to the earlier exhortation to conduct oneself worthily of the gospel (Phil. 1:27). The examples of Jesus and Paul provide the standard for the Philippians.

3:17–21. Good and bad examples. Paul draws his autobiography to a close in 3:17, addressing the Philippians as siblings and challenging the readers, join together in imitating me (symmimētai mou ginesthe). While he encourages the Corinthians, “Be my imitators” (mimētai mou ginesthe, 1 Cor. 4:16; 11:1; cf. 1 Thess. 1:6; Eph. 5:1), the compound verb symmimētai emphasizes the solidarity of the community as the members join together in imitating Paul, who frequently indicates the solidarity of the community with the prefix syn- (cf. synathlountes, “struggle together,” 1:27; 4:3; synchairete, “rejoice together,” 2:18). Paul is probably referring to the coordinated efforts to imitate his way of life as he imitates the path of Jesus from descent to ultimate glory. When Paul adds observe (skopeite) those who live according to the example (typos) that you have of us, he changes the pronoun from singular to plural but probably refers to himself, Timothy, and Epaphroditus (2:19–30) as the primary examples.

While he encourages the readers to “beware” of the negative examples (3:2), he challenges them to observe (skopeite) the positive examples. As the example (typos) for the Philippians, Paul stands in sharp contrast to the negative examples in 3:18–19, which describe the majority culture—the many, who are enemies of the cross of Christ. The fact that Paul told them this many times suggests that his message had encountered resistance during his founding visit. As he indicates to the Corinthians, the cross is an offense to Jews and foolishness to the Greeks (1:23). In Philippi especially, with its values of honor, the majority were the adversaries (1:28) and would have been enemies of the cross of Christ. These dominant views were probably a constant temptation for Philippian believers, who were now alienated from the larger society by the message of the cross. Thus the enemies of the cross could have been both outsiders as well as believers who wished to avoid the message of the cross. As Paul indicates in 1 Cor. 1:18–2:17, all who trust in human wisdom are enemies of the cross of Christ. Paul’s insistence that Jesus humbled himself to death, even death on a cross (2:8), and his own statement that he is a participant in the suffering and death of Christ (3:10) were a challenge to any who maintained the values of Philippian society. The enemies of the cross of Christ are the negative examples who stand in contrast to Paul’s own life of participating in the cross.

Paul gives a fourfold description of the enemies of the cross of Christ. His concern is not their teaching but their moral conduct. In contrast to believers, whose goal is the “prize of the high calling” (3:14), their end (telos) is destruction (apōleia, 3:19). As in 1:28, Paul distinguishes between those who are destined for salvation and those who are destined for destruction. As he told the Corinthians, the word of the cross is foolishness to “those who are perishing” (apollymenois, 2 Cor. 2:15). The telos of a life of sin is death (Rom. 6:21–22; 2 Cor. 11:15, “their telos is according to their deeds”).

In contrast to believers, their god is the belly (koilia). Paul is referring neither to libertines, as some (e.g., Bockmuehl 1998, 231–32) have maintained, nor to those who insist on circumcision (cf. 3:2), as others (e.g., K. Barth 2002, 118) have argued. He is referring to all who do not look to the ultimate goal. Koilia is metonymy for the earthly and transitory aspect of human existence. One may compare the description of apostates in 3 Macc. 7:11, who have abandoned the commandments “for the sake of the belly.”

Parallel to “their god is the belly” is the glory (doxa) is in their shame (aischynē). While believers anticipate the time when they will “be conformed to the body of his glory” in the future (3:21), the majority culture finds glory in their shame. Shame (aischynē) can refer to a variety of unregenerate types of behavior, including sexual debauchery (cf. Rom. 1:27). Paul summarizes their situation with the words setting their minds (phronountes) on earthly things (3:19). Paul has set before the Philippians two alternative ways of thinking. One takes on the mind of Christ (2:5; cf. 3:15) while the majority culture sets its mind on earthly things.

In sharp contrast to those who have their minds on earthly things is the believing community, whose citizenship is in heaven. The emphatic “our citizenship” at the beginning of 3:20 highlights the distinction between the church and the majority culture (BDF 284; cf. Sumney 2007, 94). Although the translations (NRSV, NIV) render the conjunction gar as but, Paul is actually establishing a logical reason for his call to imitation (Bockmuehl 1998, 233). This emphatic claim strengthens the identity of those who are a minority in a hostile community (cf. 1:28). The first-person plural in 3:20 corresponds to the earlier claim that “we are the circumcision” (3:3) in contrast to others. The church that is alienated from the local society and its government is composed of the citizens of a state that is in heaven, thus mightier than Rome. Rather than have their minds on earthly glory and honor in the present, they wait for a Savior from heaven who is greater than the earthly savior, the emperor, who comes from Rome. As Paul indicates in 1:27, this politeuma has its own standards of conduct and claim for total allegiance. While Roman citizenship is either the status or the goal of the majority population, believers hold citizenship in a mightier state. For them, Roman citizenship has lost its relevance (Wojtkowiak 2012, 209). Heavenly citizenship precludes the longing for status and honor on earth.

The assurance in 3:20–21 continues the narrative of the Christ hymn in 2:6–11. The one whom God “highly exalted” (2:9) is in heaven, and it is from there that we await (apechdechometha) a Savior (sōtēr), Jesus Christ the Lord (kyrios). The imagery evokes memories of the coming of the emperor from Rome to rescue the people from the Thracians. The alternative politeuma has its own Savior and Lord. Thus, contrary to the official claims of the Roman Empire, the real Savior (sōtēr) and Lord (kyrios) is the one whom God highly exalted, not the emperor. A visit from the Roman emperor is insignificant in comparison with the coming of the Lord and Savior.

In the present, however, the community awaits the Savior as it lives in the midst of the visible power of Rome. Paul frequently speaks of the church as a waiting community. While it suffers persecution in the present (cf. 1 Thess. 3:2–3), it waits for the Son from heaven, who will deliver the church from the wrath of God (1 Thess. 1:9–10). Despite present sufferings (cf. Rom. 8:18), both the creation and the community wait for the end (Rom. 8:19, 23). Thus the whole community, like Paul himself, presses on toward a goal that it has not yet reached.

Echoes of Phil. 2:6–11 shape Paul’s description of the outcome of the Savior’s coming. The Savior who once appeared in a human form (schēma), took on the form (morphē) of a slave, and humbled (etapeinōsen) himself by dying on the cross (2:7–8) will transform (metaschēmatisei) the body of our humiliation (tapeinōseōs) so that it will be conformed (symmorphon) into the body of his glory (3:21). That is, he shared the human form (morphē, 2:7), a body that was subject to death. Paul is an example for others insofar as he desires to share the sufferings of Christ, being “conformed” (symmorphomenos) to the death of Christ. Believers will ultimately be conformed (symmorphon) to the body of his glory. The language corresponds to the declaration in Rom. 8:29 that believers who share the destiny of Christ in their present suffering (Rom. 5:2–5; 8:18) will be conformed (symmorphon) to the image of the Son. Paul elaborates on this assurance in 1 Cor. 15:50–55: “We will all be changed” (15:51) and take on an incorruptible body (15:52–54).

The exalted Lord will transform believers in accordance with (kata) the power (energeia) that enables him to make all things subject to himself. Contrary to many translations (ESV, RSV, NRSV, NIV), kata is best rendered “in accordance with” or “because” rather than “by.” Thus the transformation is “in accordance with” the power (energeia) of the exalted one. Energeia (lit. “working, operation, action,”) is used in the NT exclusively for the action of divine beings (BDAG 335). According to Ephesians and Colossians, by this energeia God raised Jesus from the dead (Eph. 1:19), called Paul to be an apostle (Eph. 3:7; cf. Col. 1:29), and equips the church for growth (Eph. 4:16). Paul uses the verb energein in Philippians to describe the God who is at work (energōn) among (2:13; cf. 1 Cor. 12:6) believers. This power that is at work among believers is the one who makes all things subject to himself.

The description of Christ as the one who “makes all things subject [hypotaxai] to himself” corresponds to the portrayal in 1 Corinthians of the exalted Christ, who will “destroy every ruler and every authority and power” and reign until all enemies are defeated (15:24–25), leaving all enemies subjected (hypetaxen) to him (15:27). Similarly, in the Christ hymn all cosmic powers will acknowledge the sovereignty of Jesus as Lord. Thus Paul points his anxious readers to the ultimate power that will transform their lives. The ultimate power is not Caesar but Jesus, the one who triumphed over death.

Concluding the Argument: Stand Firm (4:1)

4:1. Paul’s model (3:4–17) and the reassurance that the ultimate power will save the community are the foundation for the conclusion in 4:1. As therefore (hōste) in 4:1 indicates, the exhortation to stand firm in the Lord is the conclusion to the argument (probatio) of the letter (chaps. 2–3) and the transition to the imperatives that follow. Before Paul commands, however, he reassures the readers of his deep emotional concern for them, using a lengthy series of appellatives that indicate his love for them. They are his beloved (agapētoi) and longed for (epipothētoi) brothers [and sisters], his joy (chara) and crown (stephanos). While Paul frequently prefaces his commands by addressing his readers as beloved (see Rom. 12:19; 1 Cor. 10:14; Phil. 2:12), the series of affectionate terms appears nowhere else in his writings. He frequently indicates that he longs to be united with his readers (Rom. 1:11; 15:23; Phil. 1:8; cf. 2:26) and that they long to see him (1 Thess. 3:6; cf. 2 Cor. 7:7, 11), but only here does he describe his readers as “longed for.” As one who hopes that they will be his grounds for boasting at the end (2:16; cf. 2 Cor. 1:14; 11:1–4; 1 Thess. 2:19), he employs the tender language of a parent, encouraging them to “stand firm [stēkete] in the Lord.” The crown, the laurel wreath given to the winner in a race, is the metaphor for the successful completion of Paul’s pastoral work. This exhortation forms an inclusio with the earlier exhortation, “stand firm in one spirit” (1:27). The presence of a hostile populace (1:28) undoubtedly is a constant temptation for the readers to return to the comfort of the previous existence. The examples of both Jesus and Paul provide the motivation for the readers “to stand firm in the Lord.” Believers “stand firm in the Lord” because Jesus Christ, not the Caesar, is the Lord and Savior who comes to rescue the beleaguered community (3:20–21).

Theological Issues

Paul’s Conversion and Change of Values

Paul offers himself as an example a second time (see also 1:12–26) as a foundation for the exhortation “stand firm in the Lord” (4:1; cf. 1:27). Having reminded believers that they stand in the middle between the beginning and the end of their existence in Christ (1:6), he presents his own autobiography, placing himself in the middle between his upbringing (3:4–7) and his ultimate destination (cf. 3:12, 14), contrasting himself sharply with alternatives that may tempt the Philippians (3:2, 18–19). Indeed, his speech is filled with sharp dichotomies—between the believing community that boasts in Christ and those who have confidence in the flesh (3:3), profit and loss (3:7–8), human achievements and Christ (3:7–8), his own righteousness (3:6) and the righteousness from God (3:9). In the downward spiral of his life that he describes in 3:4–7, he exemplifies choices between two alternatives and the moral reasoning, or phronēsis, that he commends for the readers (Kraftchick 2008, 250–51).

The real issue is the choice between confidence in the flesh and boasting in Christ. Paul speaks in sharp dichotomies because he sees no middle ground. While confidence in the flesh may be manifested in religious achievement, as it was with Paul, it may also be present in other achievements, as with the Philippian society. For our culture, confidence in the flesh may be present in single-minded pursuit of economic or political success, or even in religious self-righteousness.

The images of profit and loss vividly depict the alternatives faced by the believer. All sources of confidence have become a loss because of Christ (3:7) in order that Paul may know Christ (3:8), gain Christ (3:8), and be found in him (3:9). The sharp dichotomies indicate that boasting in Christ is not the casual commitment that is common in Christendom—an item to add to a list of achievements—but the exclusive claim of Christ on the lives of believers.

According to the popular interpretation of Paul that was dominant before the emergence of the “new perspective on Paul” in the 1970s, Paul had struggled to find a gracious God before he discovered God’s grace. While this was the experience of Martin Luther, who discovered God’s grace while reading Paul, it was not Paul’s experience. He was blameless with respect to righteousness (3:6), but he discovered that he had no righteousness of his own when he experienced the righteousness from God (3:9). Only as Paul looks back on his achievements does he recognize that righteousness was not his own achievement but the work of God’s act in Jesus Christ.