CHAPTER VIII

Mama did find out soon enough. After a few days, when the excitement had died down, she asked Orvie, “Why aren’t you in school?”

Orvie tried to tell her what he had told Grandpa, but Mama would not listen. “You get off to school now or I’ll box your ears good,” she said. “Bring your books home every night, to make up what you’ve missed.”

“But there’s no place to do homework,” wailed Orvie. “The house is all filled with people sleeping everywhere …”

“You can study in the kitchen,” said Mama.

The sudden growth of the town of Whizzbang had doubled Bert’s milk route. He had twice as many customers as before, and every day brought new ones from the increasing number of oil workers. He drove the Ford, and besides milk, carried eggs and dressed chickens to sell. He served the restaurants, boarding houses and cafés as well as private families.

Mama decided that Orvie should get his morning chores done earlier, so he could go on the milk route with Bert. He was to carry the bottles from the car to the houses, to save Bert time. The route was planned so that Bert could drop Orvie off near the school just before the last bell rang.

Wet weather and muddy roads continued through April, and Papa bought Knobby Tread tires which did not skid so much.

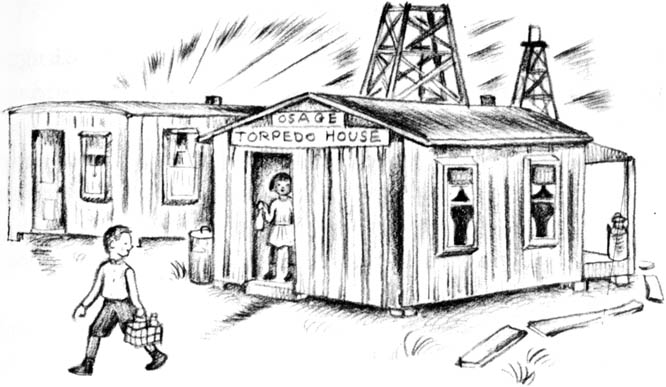

It was a wet morning the day that Orvie started back to school. The Ford made a number of stops at the row of box-car houses down around the corner. It was very early, and most of the people were not up yet. Orvie took six quarts of milk at a time in his wire basket, and ran from one house to the next. At the Osage Torpedo house, the people were stirring, and there on the doorstep stood the girl who had told him her name was Bonnie Jean. Orvie remembered about the dynamite.

“They’ve built a nitro-glycerin storage house on our place, back in the field,” he told her. “When they wash out the buckets, they go boom-boom-boom. It shakes our house all over.”

“They blow ’em up,” said Bonnie Jean, taking the milk bottle. “You better stay away from there—it’s dangerous.”

“Say—oh say …” Orvie hesitated. “You started in school yet?”

“Why yes,” said Bonnie Jean. “I started the very next day after we moved here.”

“You did? Will you be at school today?” asked Orvie.

“Sure,” said Bonnie Jean.

Orvie ran back to the car. The Ford traveled over the oil field in the section north of the Robinson farm, now called the Watkins lease, and stopped at Company houses recently built there, then came to the business part of town. It reached Bascom’s boarding house just as breakfast was being served. Two untidy girls were waiting on long tables filled with men just inside the door.

“Take the milk into the kitchen,” said Bert, “then come back for these eggs and chickens that Biddy ordered. Don’t get scared of the old woman—she won’t bite you.”

Orvie went in at the open door.

“Hi, bub! Who are you?” called one of the men.

“You’re Bert’s brother Orvie, I bet.” Biddy came forward, all smiles.

She started to pat him on the head, but Orvie dodged. He couldn’t help staring at her. She wore three different skirts with an apron on top, long pantaloons below, and a sagging slip-on sweater around her waist. She walked on crutches, dragging one foot.

“I got banged up in an automobile accident,” she explained, “one time when I was hitch-hiking. They wanted to cut my foot off, but I wouldn’t let ’em. I can still hop around.”

The men laughed and began teasing her.

“Now Orvie, my boy, put that milk out in the kitchen.”

Orvie ducked into the back part of the house, returned, and brought in the eggs and chickens.

“How’s that pretty sister of yours?” called the men.

Then Orvie saw Slim Rogers. He hadn’t known where he lived before. Slim got up and stopped him just inside the door. “I’m going to be working at No. 2 Robinson,” he said. “Tell Della, won’t you?”

“Sure will!” called the boy.

“Hurry up!” scolded Bert when Orvie got back to the car. “If you want to get to school on time, you mustn’t stand and gass all day when you’re deliverin’ milk. That won’t get us nowhere.”

“That old Biddy Bascom, she’s a sight!” growled Orvie.

On the road west from Cloverleaf Corners the Ford got stuck in a chug hole.

“Get out,” ordered Bert, “and see if you can find any fence rails.”

Orvie started up the road. The fences were all wire fences, but maybe Jess Woods would have some rails. He headed for the Woods farm.

A car came along and pulled up behind Bert’s Ford. Two girls jumped out and came running along the road. Orvie waited till they caught up. They were Edna Belle and Nellie Jo Murray. They looked fatter than ever and wore big galoshes to keep off the mud. They looked scared and were breathless from running.

“What you runnin’ so fast for?” demanded Orvie.

“Hooky Blair’s comin’ after us,” cried Edna Belle.

“He’ll hook us with his hook,” added Nellie Jo.

“I don’t see him,” said Orvie, looking back to the two cars. “Where is he?”

“He got in a car and drove it up close behind us,” said Edna Belle.

“He followed us all the way till he turned off,” said Nellie Jo.

“If he turned off, you don’t need to be scared,” said Orvie. “Does your father drive you to school every day?”

“No—our brother Ben,” said Edna Belle. “That’s him in our car back of Bert.”

“He couldn’t get past Bert without rollin’ in the ditch,” said Nellie Jo.

Just then Jess Woods came out of his lane. “Cars havin’ trouble up there?” he called.

“Stuck in the mud,” said Orvie. “Got any fence rails?”

Seeing that Bert had the help of Ben Murray and Jess Woods, Orvie walked on to school. The Murray girls flew on ahead of him, still fearful. Orvie walked slowly, thinking how silly they were, wondering why the last bell did not ring.

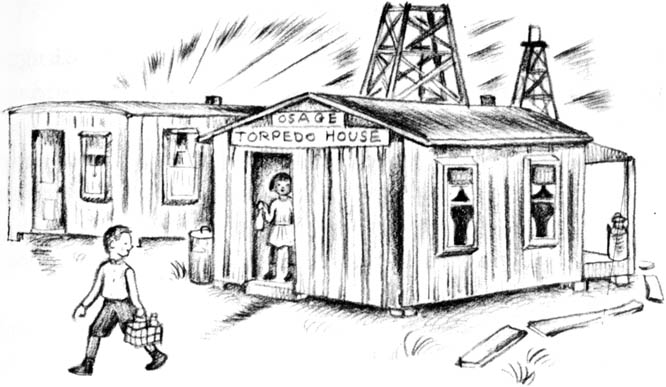

The Prairie View schoolhouse sat on a rise of ground at the next four corners. When Orvie got there, he had two surprises. He saw a new oil well on the school ground, with a derrick going up by the windows. And he saw Miss Plumley, coming from the opposite direction across a low damp field, walking. She was late, and all the children ran to the corner to meet her.

Orvie stared at Miss Plumley, forgetting to say good morning.

“Did you stick too?” he asked.

“Yes, Orvie!” laughed Miss Plumley. “I left my car and took a short cut across the field. Then I had to wade the creek.”

She looked so funny all the children laughed, and she did not seem to mind. Her feet and legs were bare and white to her knees. In one hand she carried her shoes and stockings, and held up her long skirt. In the other she carried a big bunch of pink and white roses. She walked timidly, letting out squeals each time something sharp stuck her tender feet.

“Teacher’s going barefoot! Teacher’s going barefoot!” sing-songed the children.

“I’m late,” puffed Miss Plumley. “I had to stop to pick the little stickers out of first one foot, then the other.”

“Stickers! Teacher don’t like stickers!” giggled the children.

“And Mrs. Gordon made me stop and admire her roses,” Miss Plumley went on. “She gave me this bouquet, and the roses have stickers too!”

Laughing, the children tumbled pell-mell into the schoolhouse, and Miss Plumley seemed more of a human being than she had been before, just because the children had seen her bare feet. She washed them, and put on her shoes and stockings. Orvie rang the last bell and school began.

He sat down in his seat and looked out the window.

To think they had started an oil well in the schoolyard during his absence. If he had known that, he never would have missed. The rig was much higher than the building, and from where he sat, he could see the drillers working. Maybe he could climb to the top of this derrick some time. The drilling shook the building, and ever so often the steam engine let off a blast of steam.

Orvie looked around, and there sat Bonnie Jean Barnes in front of him. There were many other new faces. Every seat was taken and some held two. He recognized certain Stringtown children, Freckles Hart and other boys from Whizzbang. School was suddenly exciting—but it was hard to keep his mind on his books.

“We’re too crowded,” said Miss Plumley,” with so many new children, but we’ll get along. Perhaps next year we’ll have a new school building. We must try to get used to the drilling outside our windows and not pay too much attention to it. Now Orvie, you have a lot of work to make up …”

A swishing burst of steam drowned the sound of her voice, and the rest of Orvie’s scolding for being absent could not be heard.

“We’ll have to talk fast, then stop and take a breath while the noise lasts,” Miss Plumley went on. The children laughed. “Orvie, will you please read the first paragraph of …”

Pz-z-z-z-z-z-t! Pz-z-z-z-z-z-t! sizzled the steam again.

And so it went all day long. Each time they started something, the bursts of steam stopped them. Miss Plumley had to give instructions by signs because of the noise. The vibration shook the building. Desks and furniture shook and shifted, chalk and erasers would not stay on the chalk-tray. Miss Plumley had a hard time keeping the attention of the children on their books, but the interruptions gave drama and zest to what had been dull and humdrum school life before.

That afternoon Orvie took his books home, intending to do his homework and get caught up, but there were interruptions there too. The men had just finished laying pipes to the Robinson house for gas.

“Golly!” he exclaimed, as the man lighted the gas burners in the new kitchen stove for the first time. “You can cook on it without wood?”

“I won’t know how to act,” said Mama, dabbing her eyes with her apron.

“Will it explode?” cried Addie, looking scared.

“Course not,” said Della. “You just turn the handles off and on.”

“It will take me a long time to get used to it,” said Mama.

“Now I won’t have nothing to do,” said Orvie, smiling. He thought of the cords and cords of wood he had chopped for the old cook-stove that now sat out in the yard under the cottonwood tree. He thought of the hours of time he had spent chopping it.

“And to think there was plenty of gas down under our farm the whole time, and I never knew it!”

There was a bright gas light in every room now, with an upturned glass shade. Each light burned from what was called a jet. Papa lighted them all and the family walked from room to room to look at the glow. The lights shone with golden brilliance even in the daytime.

“No more kerosene lamps to clean and fill, Della,” laughed Grandpa.

“I’m not sorry,” cried Della. “I’ll hide the old lamps away in the attic where we’ll never see them again.”

“Now, ain’t you glad we drilled for oil, Jennie?” asked Grandpa.

“Yes Pa,” said Mama, dabbing her eyes again.

“We’ll put in a telephone next,” said Grandpa.

“A telephone! Oh my!” said Mama.

Orvie called to Della: “Know who the new tool-dresser is at No. 2?”

“Who? Slim?” asked Della, blushing.

“Yes,” said Orvie. “He told me to tell you. I’ll go out now and tell him I told you.”

Orvie jumped on his bicycle and rode out to No. 2 Robinson. But Slim was busy and could not see him. The boilerman whose job it was to tend the steam boilers was sick and had not come, so Slim was taking his place. The engine housing had not yet been built, so Orvie could see from a distance that Slim was occupied.

Nobody knew how it happened, but some one said afterwards that the water level had been allowed to get too low before refilling the hot boiler, and this produced a flash of steam beyond the capacity of the safety valve. Suddenly the steam boiler exploded with a mighty roar, and Slim was thrown two hundred yards off into the slush-pond.

Orvie screamed. “Slim!” he yelled, pointing. “Slim, oh Slim!”

The men yelled and ran too, but Orvie was the first one there. He was sure they would pick Slim up dead or broken in pieces. He watched while the men helped Slim up, covered with mud and water from head to toe. Slim could walk, so he wasn’t killed.

“Hey, kid, get to a telephone quick!” ordered Heavy, the driller. “You got one at your house?”

“No,” said Orvie, “but we’re gonna get one.”

Slim was walking along, supported by two of the men.

“Where’s the nearest telephone?” yelled the driller angrily.

“Oh, er …” Orvie tried to think. “The Murrays … no, they ain’t got one … Old Pickering, yes the Pickerings had one put in … across the road and down a piece …”

“Get on your bike, go and telephone quick!” ordered Heavy.

“Who should I call up?” Orvie, already on his bicycle, yelled back over his shoulder.

“The ambulance, you nitwit, and do it quick before Slim dies!” came the answer.

Before Slim dies … before Slim dies … The words ringing in his head made Orvie’s legs pump faster and harder than they had ever pumped before. “Oh, I never thought anything like this would happen to Slim … he could still walk …”

Orvie was half way to the Pickerings when he remembered that they had moved away, and the place was now a dance hall. Should he go in a wicked place like that? He knew Mama wouldn’t want him to, but there must be a telephone there, and it was the nearest and the quickest.

Before Slim dies … before Slim dies … he pedaled faster.

He didn’t have time to look at the verandah that had been all glassed in around the front, nor to notice the shiny floor varnished for dancing. All he saw was a tall thin man, with loose shaggy hair.

“Telephone!” he cried out. “Telephone!”

It was lucky for Orvie that he had memorized the signs stuck on telephone poles on the way into town. Now, one of them came back to him just when he needed it: Ambulance phone 473. He got an answer right away, and a man said they would come at once to No. 2 Robinson.

Orvie hung the receiver up and sank limply down into a chair.

“Somebody hurt?” The long thin man stood beside him.

“Slim! Slim Rogers,” said Orvie. “There was an explosion and he got blowed into the slush-pond. He musta got burned or something. He could still walk, but he never said one word …”

“Too bad,” said the long thin man. He sat down at the piano and began to play softly.

Orvie stared at him. “Is it you makes all that loud music?”

“Part of it,” said the man. “We have other instruments too.” He stopped playing and looked at his own hands. “The tips of my fingers are all calloused,” he said. “That comes of having to play all night long.”

“You play all night long?” asked Orvie.

“Yes,” said the man. “Can you hear it over at your house?”

“Yes,” said Orvie. He knew the man wanted him to say something nice, so he added. “It sounds beautiful—I like it.”

The man’s sad face broke into a smile. “I’m glad,” he said.

“Some folks say we ought to try to get rid of your dance hall,” Orvie went on, “because you have drinking, gambling and dancing going on over here. But we never hear any loud noise nor yelling—only music, so Grandpa says we can’t complain. Your music’s pretty—it can’t harm us none. I wish Della could hear it—she wants a piano, so she can take music lessons.”

The man smiled again. He turned to the piano and began to play as Orvie ran off to his bicycle.

When he got back to the oil well, the ambulance was there, and Slim was lying on a stretcher. He smiled at Orvie but did not speak.

“Is he hurt bad?” demanded Orvie.

But Heavy and the other men did not answer. They loaded the stretcher into the ambulance. Its rear door closed with a bang, and its siren began to screech as it rolled out into the road. Orvie had seen ambulances go screeching by many times before. It was a common enough sight in the oil field, and had not meant anything. Now it was different.

“Is he hurt bad?” Orvie asked again.

“Don’t know,” said the driller. His voice, usually so cross, was kinder now. “Hope not. You go tell your sister what happened.”

“Della?”

“Yes,” said Heavy. “Slim will want her to come to the hospital to see him, you bet.”

“Are they takin’ him to the hospital?” asked Orvie.

“Sure,” said the driller. “They’ll fix him up in no time.”

“Drilling oil wells is dangerous work,” said Orvie.

“Sure is,” said the driller.

Della cried and cried when she heard the news. She cried again when she came back from her first visit to the Tonkawa hospital. Slim was badly burned on his back and legs, and had to have considerable skin grafted on. He was to be in the hospital for two months or longer.

“Two months,” said Orvie. “I’ll sure miss him.”