Chapter 12

Take Aim: Set Your Sights on What Matters Most

In this chapter, the word “most” is what I want you to embrace.

What is the most important thing right now? Not what is more important between many choices, but what’s the most valuable—the top, highest, maximum, chief, greatest, uppermost. You get the point; that is where we all need to take precise aim.

In the infamous words of Yogi Berra, “If you don’t know where you’re going, you might not get there.” Consider that funny line and start to carefully consider how you set your priorities at work or at home.

Do you know your priorities? Are they effective? Are there things you’d like to accomplish but never seem to get to? Do you find distractions derail you, or do you notice at all?

For many of us, it’s similar to setting out on a journey without determining a specific destination (i.e. an address, a hotel, a landmark, etc.). In your mind, you’re just headed in a general direction.

Retracing your steps later, you see how you were all over the road, wasting energy and time along the way. In our age of infobesity and interruptions, our lives can meander in wild twists and turns. Many times, we may not even notice we do this at all.

We won’t get very far unless we take aim at what matters most.

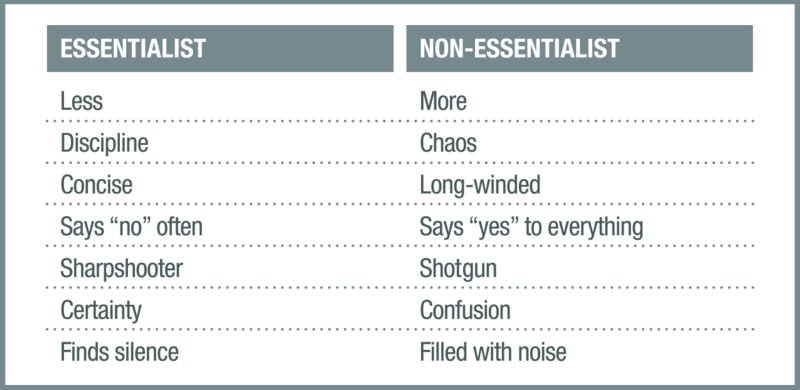

Essentialists versus Non-essentialists

In his remarkable book Essentialism, Greg McKeown sets out powerful ways to avoid the burden of excess by embracing fewer things in your daily life. He challenges people to become essentialists. Those burdened by excess are non-essentialists.

An essentialist chooses to focus on a few, vital things; and a non-essentialist has someone or something else set their priorities and chases many things.

The side-by-side comparison is stark:

McKeown is realistic in his message. “It’s not just the number of choices that has increased exponentially, it is also the strength and number of outside influences on our decisions that has increased.”1

No More Deafening Noise

Our lives can become flooded with more and more stuff. Moment to moment, our minds are crammed to the brim—like closets, basements, and bedrooms in a hoarder’s house—teeming with useless, trivial information and ongoing diversions that seem important in the moment and prove to be of little value later on.

What’s more, we have so many choices to make. Go online to rent a movie and there are thousands and thousands to consider. Head to the grocery store and look for pasta and sauce; there are dozens. Look for games in the app store and you can wander for hours looking at an endless list of options. Most of it is overwhelming and confusing, especially if we don’t have a filter to determine what’s right versus what’s to be avoided.

A techdirt.com article on video streaming brings attention to our abundance of choices, “Nearly half (47%) of US consumers say they’re frustrated by the growing number of subscriptions and services required to watch what they want, according to the thirteenth edition of Deloitte’s annual Digital Media Trends survey. ‘Consumers want choice—but only up to a point,’ said Kevin Westcott, Deloitte vice chairman and US telecom and media and entertainment leader, who oversees the study. ‘We may be entering a time of ‘subscription fatigue.’”2

We feel the steady loss of energy and time, like water pouring through our fingers. Everything that beckons for our attention seems vital, yet very few things are vitalizing. As the noise levels increase, our daily lives don’t feel much like living. Instead we feel we are just spinning in place.

Pointless Routines

For one midlevel manager and father of two, it took hitting the wall one day to admit the pointlessness of his busy, futile, daily routines.

Every morning Steve would wake up and immediately check his smartphone. He’d scan multiple e-mail accounts, check weather, stocks, news feeds, social media, and sports. He navigated his smartphone like a Swiss Army knife, clicking and swiping from place to place in nanoseconds.

In a matter of moments, his brain was humming. It carried on through the commute, into meetings, and on the way home.

When he’d walk in the door at home, he was agitated and couldn’t focus. Family life didn’t move the same way. He couldn’t settle down to patiently talk with his wife and complained in his head that she should get to the point faster.

While helping his kids with their homework, an internal battle waged as he tried to focus on teaching them as he checked his phone for updates, e-mails, and social media. This routine of self-induced distractions, constant multitasking, and dispersive attention became his new normal.

Then Steve and his family went on a weeklong vacation to the mountains. They were so far away from the big city that technology not only didn’t work, it also seemed out of place in that beautiful environment.

Fast-forward seven days. He returned from vacation happy, calm, and centered. He no longer wanted to be the proverbial gerbil on the spinning wheel and began to limit his time checking his phone.

Steve’s family and co-workers started to notice he was a different person. He was a better listener, he slowed down more, he was getting things done, and he was present in the moment.

A Minimalist Decision: Keep It Simple

There’s wisdom in the adage “less is more.”

In an era of supersaturation and excessive choices, our options can quickly overwhelm and permanently paralyze us. It’s not just daily media usage and technology access, but the vast array of possible alternatives from investments, clothing, colleges, salad dressings, strategies, and vacation spots. According to Alina Tugend, in a New York Times article about the paralyzing effect of facing too many choices, “An excess of choices often leads us to be less, not more, satisfied once we actually decide. There is often that nagging feeling we could have done better.”3

Decision-making has never been harder, and our focus has never been more strained.

General Bernard Montgomery, a primary architect of the D-Day invasion, drafted a one-page, hand-written directive to orchestrate the movement of more than 156,000 troops on June 6, 1944. At the bottom of the directive, he wrote the word “simplicity,” and underlined it three times.

Simplicity was the key to the invasion’s success. The single-minded focus of the commanders and the troops in the midst of that highly complex operation was remarkable.

A minimalist movement has taken root in our culture, providing fewer moving parts to run our lives. Millennials have quickly embraced this movement.

We’re more than overdue, since in the United States today, as mentioned by becomingminimalist.com, most homes have more televisions than residents, and we consume 50% more material goods than just 50 years ago.4

Aim Small, Miss Small—Tips to Direct Your Focus

In the Army, snipers are a breed apart. They train extensively to achieve high levels of concentration, patience, and precision. Those that I have met are remarkable professionals and terrific human beings, each with a willingness to share aspects of their craft openly. One of their mantras is “aim small, miss small.”

This means that when they select a target in their scope, they intentionally focus on an even smaller part of the object (e.g. an edge, a button, a small part of an item). The basic idea is that if you miss by a few centimeters, you will still hit the target.

The same is true with taking aim in our daily activities and routines. We need similar discipline.

Here are five specific ideas to help you take aim and prioritize a few essential things in your life. I’ve included additional insights that address potential objections, actions, and results (think of them like OAR, for short, to keep you “rowing” in the right direction).

- Idea 1: A step forward: a silent retreat. Consider how moments of quiet contemplation can provide the peace and serenity we need to go deeper to define what matters most for each of us. In my own circles, I’m encouraged to go on an annual retreat. Every year, I resist. It is three days of silence that seem unbearable on Friday but a gift once I’m finished on Sunday afternoon. During that time, I set bigger goals, assess lifelong dreams, and reset myself while in prayerful contemplation.

- Objections: I’m busy; I’ll do it later; it won’t work for me.

- Actions: Schedule time away; do a turn-it-all-off weekend; wake up an hour earlier with no technology access.

- Result: Listen to what you hear; get some rest; feel at peace.

- Idea 2: Write it down. After telling one of his corny jokes, the infamous Irish comedian Hal Roach used to say, “Write it down! Write it down!” Lest we forget, it’s critical to jot down our “north star” goals. David Allen, productivity speaker and author of Getting Things Done, says writing things down can help you capture and clarify what is important and what can be discarded.

- Objections: It’s just going to change again tomorrow; my boss or significant other sets my agenda, not me; I like to keep my options open.

- Actions: Get a coach or advisor to help you set a vision; buy a pack of Post-It Notes, frame your big goal, and post it somewhere that you will see often.

- Result: Making a decision to set a specific course will empower and direct you.

- Idea 3: Make a private, then public pact. As social beings, setting priorities transcends us personally. Our goals and dreams affect us, as well as others in countless ways. Our co-workers, friends, kids, and clients all feel a difference when we focus on fewer things with greater intensity and purpose. That said, we need to share our plan to simplify our lives. After all, they’re not mind readers.

- Objections: If I change my plans, I will lose credibility; it’s a personal matter; I don’t feel comfortable sharing.

- Actions: Make a short list of “safe” people with whom to share your plan; schedule time to declare your objectives to them; ask others to spread the word.

- Result: People around you can help keep you accountable and support you.

- Idea 4: Keep it in the galaxy—in time and space. Setting a “north star” should not be a far-off, distant dream. We make our vision real by keeping our feet planted on earth and making time and space for it. This means moving schedules around and removing obstacles that impede our progress.

- Objections: I’m not a good planner; my schedule changes moment to moment; my willpower is weak.

- Actions: Read the book Getting Things Done by David Allen; review your calendar and block off time; create a physical space at work or home to reflect on your progress.

- Result: Developing a stronger sense of realism and willfulness.

- Idea 5: Throw away something. Find an item that you don’t use and don’t need and throw it in the trash. Clutter comes in many forms. You need to develop the habit and willpower to rid yourself of these excesses. They won’t stand up and leave on their own.

- Objections: I might need it someday; that seems drastic; I paid good money for it.

- Actions: Find a shirt or pair of shoes you don’t wear and give them to charity. Delete an app on your phone you haven’t used in the past six months.

- Result: Uncluttering your world will encourage more minimalism.

Post It: Simplicity Isn’t Complicated

As Ronald Reagan once said, “there are no easy answers, but there are simple answers.” Our tendency is to complicate our daily lives much more than they need to be. I certainly do this, and maybe you do, too.

There’s far too much to juggle in our lives: professional life, home life, finances, technology, religion, activities, expectations, cars, entertainment, hobbies, gossip, exercise, shopping, apps, news, food, threats, drama, events, deadlines, commutes, meetings, healthcare, image, sports, music. The list is long and the likelihood for complexity and complication is great.

What really matters? It’s not 50 things. It’s maybe 5—and should be fewer.

It helps me if I write my defining “go-to” goals in a few words on a small Post-It note. I put it on my desk or on a bathroom mirror as a visible reminder, and I remove all the clutter around it.

These Post-It notes force me to keep my goals simple. It’s not a list. It sits there stuck to my desk, my refrigerator, or in my bathroom, unpretentiously telling me what I’ve decided really matters.

That’s it. Bam! Three words (“write next book”); two words (“listen more”); four words from the Chicago Cubs (“try not to suck”).

You get the point.

To Simplify Is a Deliberate Decision

Mindfulness expert John Kabat-Zinn once advised, “Voluntary simplicity means going fewer places in one day than more, seeing less so I can see more, doing less so I can do more, acquiring less so I can have more.”5

There’s much to be gained by managing fewer moving parts.

Think of your life like a machine—the more components, the greater the possibility of something breaking and needing repair.

One of the best bits of advice on this topic comes from a small book, The Elements of Style. In it, the authors Will Strunk and E.B. White provide practical ways to improve writing. Their three-word gem inspired me to write my book BRIEF:

“Omit needless words” (point #17).

- “A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts.”6

Brilliant advice.

In our lives, only a few things are necessary.

The paradox is we have to give something away to get something in return. Are we givers or takers? Are we filling our lives with excess stuff—hanging on to an old pair of boots, an extra word in a pointless meeting, more clicks and swipes on our phone, or giving into another tempting distraction.

Like the song in the Disney animation film Frozen exclaims, “Let it go, let it go, let it go!”

Rewind

- Consider your priorities for your work or your life? How many are there? Does your list seem overwhelming? Does it lack focus?

- What actions can you take today to simplify your life?

- Which of the suggestions outlined in this chapter could you adopt today?

[Brief Recap]

When we keep things simple in life we are more focused, productive, and present. When we don’t, we feel a heavy burden that weighs us down and makes us wander slowly.

{Tune-in}

Set your sights on fewer priorities, not more activities, choices, and stuff.