The mockup of the mosque was completed, and it was nothing short of amazing. Every room was recreated like a balsa wood dollhouse. Double swinging doorways, stairways, anterooms, lunchrooms, offices, prayer rooms, classrooms, even the bakery and bookstore inside the building were duplicated. Every wall, door, ceiling, and floor was painted in the exact color as the day in question. I suddenly realized why it cost so much money to make a movie. I'd use this mockup as a model for every cop involved, clarifying where they were when they first responded, and what their actions were thereafter. I'd be able to construct an exact timeline of the day with this information.

The idea was to develop a three-tier system: first tier, anyone who was inside the mosque; second tier, men who were directly outside the mosque; and third tier, men who were stationed outside the perimeter of the building behind the barricades. Phil and Vito were tier one—numbers one and two, Padilla, Negron, tier one—three and four, Rudy Andre, tier one—five, and so on. By doing this, I could justify every cop's actions. If the cops entered that building in accordance with their duty and they were acting properly and in good faith, a defense attorney couldn't say that the FOI men were acting in self-defense, trying to protect their place of worship from armed interlopers, the cops. However, once the ball was set into motion, I'd have no choice but to interview every cop that was in those first two tiers. If I missed one interview, the defense, having access to the same tapes and roll calls, could say we were trying to hide testimony.

I listened to the 911 tapes, cataloging all arrivals from the first unit responding to the last. Then I dispatched Vito to every precinct involved, where he retrieved the individual roll calls for the day. Those roll calls gave me names to go along with the sectors and foot posts I'd heard on the tapes. I determined that sixty-seven cops made it into tiers one and two. Of these sixty-seven, only eleven of them actually made it into the building. Of these eleven men, five witnessed the beatings, four of them victims themselves—Navarra, Negron, Padilla, and Cardillo. Three other cops left the lobby immediately, rushing the wounded to the hospital, leaving three cops on the scene to detain the prisoners and secure the premises. Three cops was hardly the premeditated invasion Minister Farrakhan and his consorts were claiming.

The hard part was actually interviewing every one of these cops. What should've taken no more than two weeks went on for an exhausting four long months. The guys would come in and lose sight of the fact that I was investigating the murder, not the bosses on the scene. Some guys came in with prepared statements about the malfeasance they'd witnessed on the scene, none of which was relevant to the case. Others came in as a group, screaming over one another, swearing, vowing vengeance against the brass. As it turned out, some of them weren't even present at the mosque. The noise inside the already loud 2-8 squad was becoming unbearable.

During these frustrating interviews, I learned that a secret organization had been formed, the CCC, Concerned Cops for Cardillo. At their weekly meetings, cops from all over the city would bitch and moan about what happened, and what didn't happen, what they were told to do, and what they were told not to do. They couldn't let go of the betrayal. The longer the investigation went on, the more angry they became. The men were formulating their own investigation, which they believed, would help facilitate my investigation into the job's lack of action, which made them responsible for the riot, and for letting the guilty parties go free. Were they right? Hell, yes, they were, but it wasn't my job to prove or disprove any of that. My job was to catch a killer, and it was becoming increasingly hard to keep sight of that. I was invited to the CCC meetings, but I declined. I'm sure the cops started to view me as a Benedict Arnold, but I had to think about the case. If One PP found out I was going to some secret meetings to conspire against them, I'd be yanked off the case in no time. I think maybe some of the guys knew that and understood.

The interviews with the cops were on a fast track to nowhere. My frustration was starting to show. The moment a cop sat down at my desk, I held my hand up, closed my eyes, and said, “I'm telling you now, I don't want to hear about the brass. Just give me the answers to the questions I'm asking, nothing more, nothing less, because I have to put it on paper.” Putting it on paper meant it was going on a five, which would appear on court documents. Whatever these guys said was going to be picked apart by defense attorneys.

I was peeing in the wind. Everything I said just fueled their desire to not only impeach the job, but me as well. Cops started to appear with intimidating PBA delegates, who began questioning me. Was I also investigating the other assaults of Navarra, Padilla, and Negron? What about the other aided case cops who were injured in the ensuing riot? This role reversal was time-consuming. While I was tap dancing with these cops and their delegates, Phil's murderer roamed free. As frustrating as it was, these cops stayed their pledge to Phil; they'd never forget him. I realized that we were all reading the same book, just on different pages. That road to hell was paved with good intentions.

Till finally one day, the pointed questioning of one particular delegate hit me center mass: “What about the other victims?” That's when I snapped.

Everything came up on me at once. The paranoid Lieutenant Muldoon, the secret meeting with Tom in the shithouse at One PP, the alienation from my partners, the deplorable looks from other detectives, and to now be accused by the very men who allegedly “had my back.” I lost total control, slamming my hand on the desk over and over. I stood up, pointing at both delegate and cop. “The balls of you two to come in here, on my and Phil's dime, with your smug attitudes and accusatory questions. I myself was a victim. Did you two forget that? Who's investigating my assault? Do I give a fuck?”

We were at a tour change, so the squad room was top heavy with overlapping detectives signing in and out. The cells were filled to capacity with prisoners. There were other cops seated, waiting to be interviewed. Typing stopped, conversations were halted, interviews suddenly broke off, a cricket chirped somewhere. It was dead silent as I walked over to the waiting cops, my feet hitting the floor, sounding like explosions. I stood in front of the uniforms; the words just tumbled out, “I'm telling you guys for the last fucking time, I don't give a fuck about the brass.”

A grizzled hairbag of a uniform stood up, “What, did you forget what this was all about? You were at the grave site, Jurgensen. You heard what was said. We ain't forgettin'. What, did you all of a sudden forget about Phil?”

My faced flushed. I felt both hands ball into fists. Thankfully, Bart Gorman appeared in front of me, placing both his hands on my shoulders. He calmly said, “Randy, I'm gonna talk to the guys. Get yourself a cup of coffee.”

I was keenly aware that every cop, DT, and boss had eyes on me. Slugging this cement-headed cop would only make me more of an outsider. I shook my head in disbelief and walked the fuck out.

I needed to get outside, away from the blue brethren. I walked toward 125th Street. Harlem always had a soothing effect on me, but today, nothing. And that's when I heard him calling my name. I turned. It was Vito.

He jogged to me, though I kept walking, determined to get as far away from the precinct as possible. He caught up, falling in step with me. He didn't say anything. I wanted to blame somebody, and he was the perfect blue target. He represented them, the cops. G'head, Vito, say something. Defend them. I fucking dare you. I wanted to say this but my jaw was clenched shut.

We must've walked three long blocks when he finally broke the silence. Completely out of breath he said, “You know, Randy, your legs are longer than mine. You mind slowing down a bit?”

I looked at him. The angry bubble I was in suddenly burst. I slowed. My breathing leveled off. I stopped, resting on a parked car. He placed both his hands on the hood, catching his breath.

He looked up at me, face flush and sweaty. “Gotta stop smoking.”

We both laughed and continued laughing. It made me realize I had walked out on him. And he had walked out on all of them, so he could walk with me, his partner. Vito, in my eyes, was no longer the victim. He personified what this investigation was all about, taking care of each other. On that day, Vito Navarra became my partner, and I was damn proud of it.

The nuclear cloud from the explosion didn't take long to reach me. One day to be exact. I was ten-two to the 2-5, forthwith. That meant Lieutenant Muldoon wanted to see me immediately; do not pass go. I did as requested.

He was in his usual position, facing the wall, when I entered his office. He quickly spun in his chair, looking directly at me, not a good sign. He shot out of the chair, closing the door to the office. He screamed, “You got cops coming to the 2-8 from all over the city? I told you, you need to interview somebody, the request comes from me. Now I am goddamn tired of your insubordination. That's two times you disobeyed a direct order, and guess what, it ain't gonna happen again. You wanna know why? Because you are now reporting here, to this office. You and your partner are working out of the 2-8 no longer, and I don't give an infinitesimal fuck who you got making the next phone call for you, because trust me, Jurgensen, my dick is bigger than yours. From now on, you talk to a cop, I'll get him here. If he needs a tour change, it comes from here. You're down to your last out. You following me?”

The purple vein pulsing on his forehead and the very fact that his eyes hadn't moved from mine throughout his entire rant told me to tail the fuck down. I nodded, “Yes, Sir. I'll let you make the phone notifications.”

“No, no, no, you got it wrong. You aren't letting me do shit. I'm the fucking landlord; you're the tenant, and don't you ever forget it.” With that, he tapped his glasses back up his nose.

“Anything else, Lieutenant?”

“Yeah, there is. What was that little statement you made, that you don't give a fuck about the brass? What did you mean by that? You got some wild hair up your ass? You gonna start questioning superior officers?”

Though he'd taken what I said completely out of context, I did feel a flush of embarrassment. “No, Sir, that's not what I meant. What I said was that I didn't want to hear anything about the brass from the cops. All I wanted them to tell me was what their actions were on the day of occurrence. None of that stuff about the bosses was pertinent to the case, that's why I said that.”

I knew he was jacked into the 2-8. How else could he know about the statement? I thought the worst of it was over, but that's when he hit me with his bombshell. “I don't know what the hell you're doing, but I do know that you're collecting enemies by the second. Why in the fuck is the Cardillo family saying to the DA's office that we're whitewashing the investigation of the superior officers?”

I didn't think it was humanly possible for him to get louder. “What investigation of the superior officers?”

I was momentarily stunned. Someone influential had the Cardillos' ear, and it had to be a pissed-off cop. “Sir, I know nothing of that. Trust me, there is no investigation of any superior officer, because a superior officer did not shoot Phil. I'll call Van Lindt and straighten this out.”

He turned from me, sitting at his desk. “Is there anything else, Sir?”

He lifted his hand up as if he were shooing away a butterfly. I turned and was happy to walk out, barely in one piece.

Vito lingered nervously by a water cooler. He'd heard the screaming. I tilted my head at him to follow me. When we were out of earshot on the stairway, I asked, “You ever make any of those CCC meetings?”

“Absolutely not, Randy. Yeah, I been asked to go, but that's the last place I wanna find myself. This whole thing is hard enough, you know what I'm saying?”

“Okay, what about the Cardillos? You saying anything to them about the case?”

“No, Randy, I haven't spoken to the family since the funeral.”

“Well someone is giving them the wrong information, and it is only going to fuck us up in the long run. Don't say anything to anyone about the case. Maybe we're better off being out of the 2-8.”

He was surprised, “We're out of the 2-8? Where are we gonna work?”

I jabbed my thumb up to the ceiling, “Upstairs with Lieutenant Queeg.”

My first call was to Van Lindt. He verified that Phil's Uncle Frank and Aunt Tessie, acting on behalf of the Cardillo family, made it clear that they were on top of the investigation. “They're under the assumption that superior officers are stonewalling, because they may have something to hide in regard to the shooting,” he said. “They don't have anything to do with this shooting, do they, Randy?”

“No, John, not with the shooting.”

“Well, where are they coming up with this information? It's only going to screw us up in the trial if they appear to be hostile, Randy. You've got to choke this immediately.”

“I'll handle it, John.”

Frank and Tessie Cardillo were old friends. They'd owned a florist shop in east Harlem for thirty years before folding up the tents and relocating to Astoria, Queens. I wasn't looking forward to this visit, because yet again, I'd be placed in the middle of this investigation, having to justify my actions, or what the Cardillos had perceived as inaction. I had to allay all their fears. I needed to reassure them that a cover-up by One PP wasn't impeding the investigation. It was my job to turn them from the gossip to the truth. I knew it was going to be difficult, because it was Phil's partners who had their ears.

I hadn't seen either Frank or Tessie Cardillo since the funeral, so this was somewhat of a tearful reunion. I briefed them on what I viewed as the progress of the case, and I assured them that I was not motivated by anyone or anything other than a deep-rooted desire to see justice prevail. Phil's killer, I promised, would be caught.

They wanted to know why I wasn't investigating the job's hierarchy. My answer was direct: no member of the NYPD shot Phil Cardillo. A Muslim who was present at the mosque shot and killed him, and that was the only person I was focusing on. I went on to explain that the job was preparing its own investigation, the Blue Book, into what had occurred that day. But I'd have nothing to do with that part of the investigation.

They seemed less anxious after I made things clear. We hugged, and then I plaintively asked that they not make any calls to the DA's office, the PBA, or any other cops regarding the case. I left them my home number and told them if they had any questions about the case, I'd be the only one to talk to, since I was the only detective working the case.

I tried to remain above board with Muldoon. The next series of interviews were conducted his way, one at a time. He insisted on knowing exactly what was going to be asked of each cop, then he would call the individual cop's command, and he'd work out a tour change with that precinct's roll call. Getting cops into the 2-5 took twice as long as the whole interview process took in the 2-8. I got tired of playing games. The job had become a tangle of blue tape, and that was becoming a liability to my case. The clock was ticking, and it was time to get in the game. I was going to handle Muldoon the way I'd handled a million or so third-grade perps who tried to derail one of my investigations with divisive behavior. Muldoon was a simple math equation that had to be solved. They were going to be fed disinformation, much the way I had been fed it. I would create an adjunct case, one that had nothing to do with my real investigation. I'd write up meaningless fives and requests that I knew would take forever to acquire. This would keep all of them in a spin cycle far away from my real investigation.

I gave Muldoon a list of thirteen cops, all of whom I'd already interviewed. While he dragged his feet calling them in, I'd be out in the field, talking with the cops who mattered.

By doing this, I'd turned a page, not only in this case, but also in life. I was slowly crossing over the line. I saw my insubordinate behavior as the only card I had to play. I needed to be left alone to conduct a proper investigation. In essence, they pushed me over that line. The problem is, once you've crossed the line, it's hard to distinguish between right and wrong and impossible to cross back over. This was the beginning of my end.

While he was on the phone chasing his tail, I had cleared all of the cops, and I had the beginnings of an excellent timeline. The first third of the case was set, the identification of the cops. The next part of the case would bring me face-to-face with the other witnesses, and hopefully, the shooter. But without access to the mosque or any of its members, it would be nearly impossible to develop a timeline for the Muslims. I had no one to interview. This next part would have to be carefully plotted and covertly executed. Like before, I'd have to bring the mosque and its members to the cops. But first, I had to attend to some pressing personal business. I was getting married.

All the police were interviewed, their statements secured in the fives. This was the perfect opportunity to take a break in the action. Though the wedding was planned months in advance, Muldoon had no idea I'd be taking off for nine days.

His head was buried in paper when I entered his office. I knew this would lead to another hissy fit, so I decided to leave the door open.

“Lieutenant Muldoon?”

He didn't acknowledge me. “Just want you to know, Sunday is my wedding, and starting in,” I looked at my watch, it was nearly 6 p.m., “ten minutes, I'm on vacation till next Monday.”

This got his attention. He spun around in that noisy metal chair. “No, you're not.”

“Yes, I am.”

He held out his hands, palms facing the ceiling. “You can't just walk out. What about the men I'm bringing in for your interviews?”

“Well, Sir, I realized that I had already interviewed those men. All the cops at the scene are cleared. All preliminary interviews on our side are complete.”

I saw cold realization crawl across his face. He knew he had been played, but what could he do other than try to retain a sense of leadership, if not to me, to himself. “Jurgensen, you can't just walk out like this.”

“Watch me, Sir.” I turned and walked out. He didn't scream, rant, or rage. He was now the manageable math problem he presented himself as, and I was truly over the line.

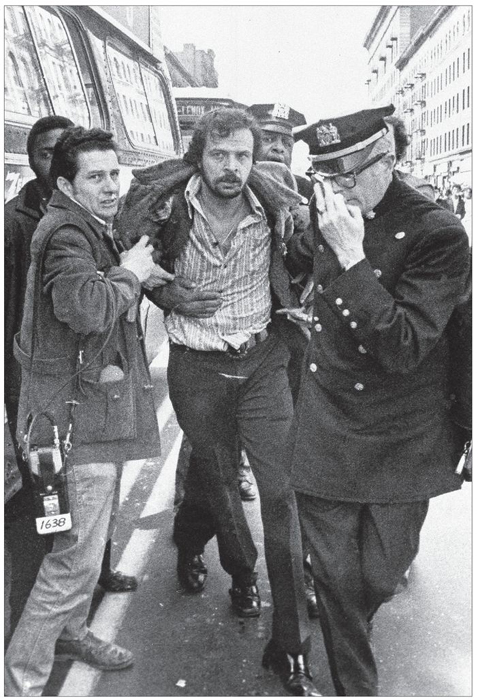

From left, Patrolman Jerry Harvey, Patrolman Lou D'Alessio, Detective Randy Jurgensen, Patrolman Gregory Harris, Deputy Inspector Jack Haugh, April 14, 1972.

Photo: Jerry Mosey, courtesy AP/Wide World Photos

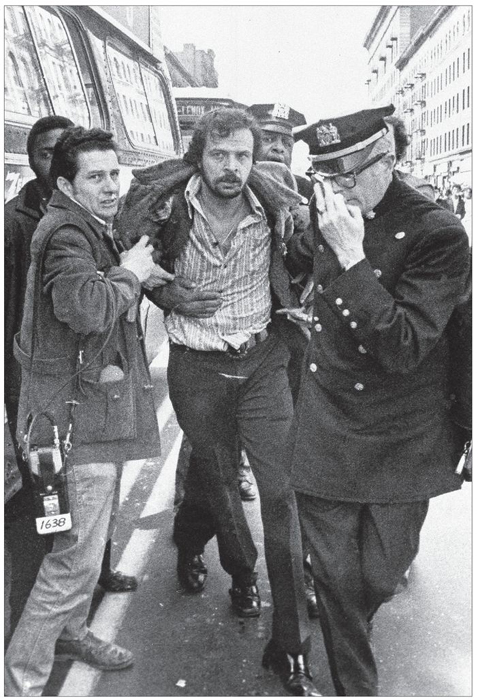

Foreground, from left, Deputy Inspector Jack Haugh, Detective Randy Jurgensen, Patrolman Raymond San Pedro, Patrolman Lou D'Alessio, April 14, 1972.

Photo: Eddie Adams, courtesy AP/Wide World Photos

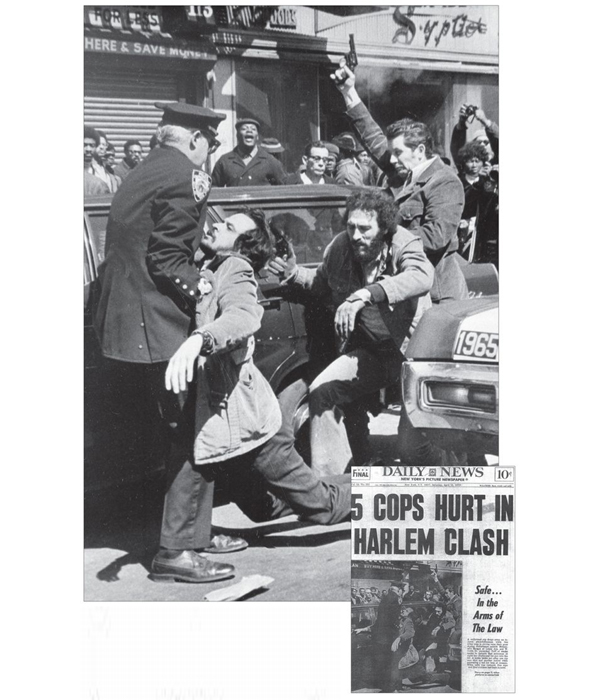

Inset: Front cover of the New York Daily News.

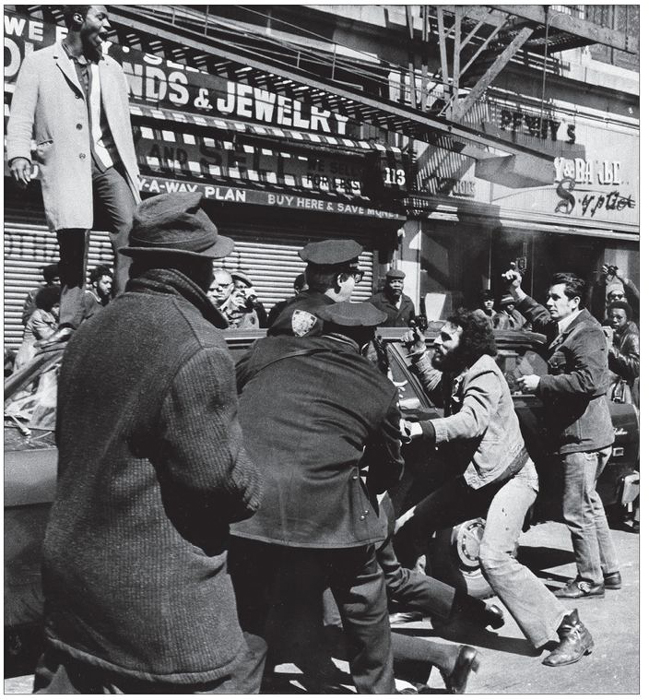

Above: Foreground, from left, unidentified civilian, Patrolman Gregory Harris (back to camera, bending), Deputy Inspector Jack Haugh (standing), Patrolmen Raymond San Pedro and Lou D'Alessio (with guns). Legs on ground are Detective Jurgensen's. April 14, 1972.

Photo: Eddie Adams, courtesy AP/Wide World Photos

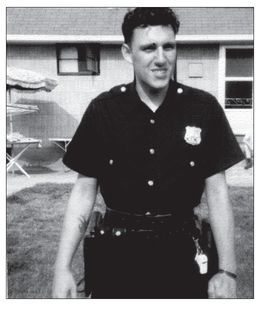

Left: Patrolman Phillip Cardillo.

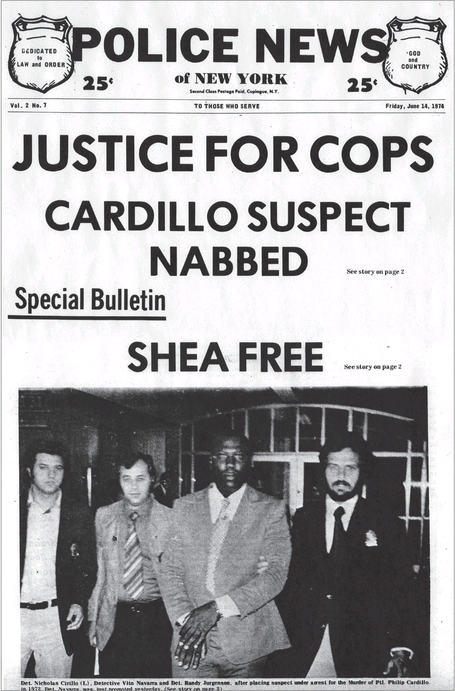

The arrest of Lewis 17X Dupree makes the front page of Police News. With Dupree, from left, Detectives Nick Cirillo, Vito Navarra, and Randy Jurgensen.

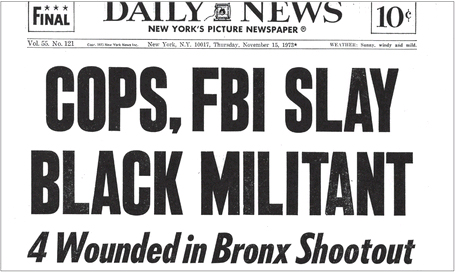

The NYPD ends the hunt for Twyman Meyers.

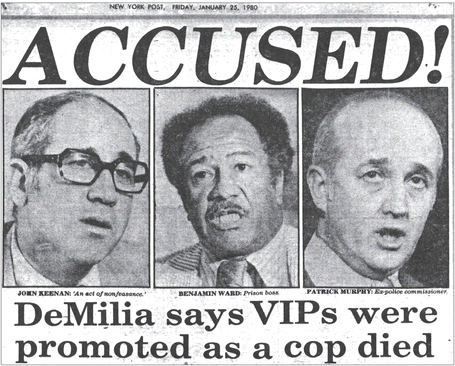

The New York Post headline demonstrates PBA President Sam DeMilia's feelings about the case.

Above: Randy Jurgensen (far left) is presented with the Isaac Bell Medal for Bravery for capturing cop killers Albert Victory and Robert Bornholdt by Sgt. Walter Kirkland (far right), having refused to accept it from Mayor John Lindsay (second from left) or Police Commissioner Patrick Murphy (second from right), May 1971.

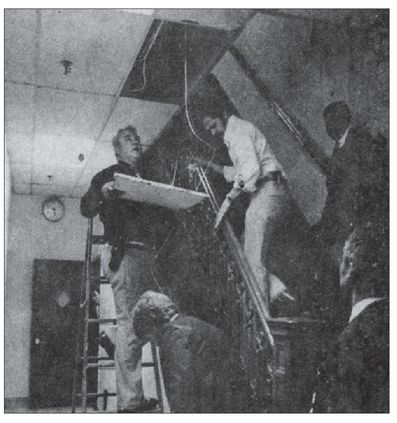

Left: Detective Jurgensen and ADA Jim Harmon retrieve bullets from the ceiling of Mosque No. 7. Holding partition is Detective Richie Wrase; standing on stairs is Detective Jurgensen; leaning against wall is defense lawyer Saad El Amin and standing at the bottom of the stairs is defense lawyer Edward Jacko.

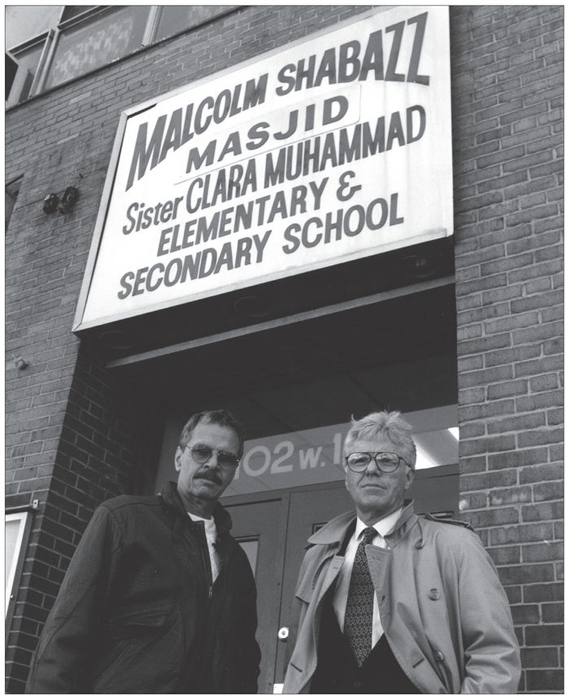

Above: Randy Jurgensen and Jim Harmon (right) return to Mosque No. 7, 25 years on, April 14, 1997.

Right: The helmet worn by 18-year old Randy Jurgensen when wounded on Pork Chop Hill, Korea. It is now on display at the West Point Museum.

Above: Randy Jurgensen reconnects with New York City Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly, June 2006.

Left: Randy meets Joe “Donnie Brasco” Pistone at their old rendezvous, the Saint George Hotel in Brooklyn, NY, August 2006.