Chapter 8

The Murder of Ethel Christie 1950–52

‘After she had gone, the way was clear for me to fulfil my destiny’.1

Changes were afoot at 10 Rillington Place. Kitchener left the house in mid-December (he died in Worthing in 1964). In January 1950, Christie and his wife were briefly alone there. His job at the Post Office came to an end on 4 April. Christie claimed he had been ill, and off work, and that on his return he was escorted from the premises by two investigating officers, being sacked due to ‘changes affecting the character (misc.)’. He soon found other work and from 24 April he was a despatch clerk for Messrs Askey’s, a biscuit firm, of Kensal Road, leaving on 19 May. On 12 June 1950 he began working as an invoice clerk at the British Road Services, a nationalized industry which ran the country’s road haulage services. He worked at the Shepherd’s Bush depot at 192 Goldhawk Road and was remembered as being ‘bad tempered’, although his work was ‘quite satisfactory’. He did First Aid and as a colleague later said, ‘He always made a terrific fuss over just a scratch. I’ve gone to him with only a little cut on my thumb and came away with a huge bandage over it’.2

Christie also took a limited part in the Road Service’s social activities. A colleague later recalled, ‘It always seemed to me that he was trying very hard to be popular and not quite making it. When he refereed British Road Service’s football matches he would trot about the pitch very much in command of the game’. He once accompanied his colleagues to a Christmas dance in a sergeants’ mess in White City and was encouraged to choose a girl to ask to dance, but he failed to do so.3

Christie also became heavily involved in trade union matters, which suited his left-wing politics (he also read the left-wing Daily Mirror, but on Sundays the right-wing News of the World). He was elected chairman of TGWU (Transport and General Workers’ Union) Branch 38 in 1950 and was re-elected in 1951 for two years. He was also grade representative of the West London Group. He was chairman of the London Delegates’ Conference in 1950 and was re-elected in the next year. He was nominated for the NEC of the TGWU. A doctor later reported that he ‘takes great pleasure in telling me of his activities in trade union work’. Ironically, Denis Nilsen was also a staunch trade unionist and Dr Harold Shipman was left-wing too.4

On 22 December 1949 there appears to have been the suggestion that Christie take over the tenancy of the whole house himself, while a letter of 26 March 1950 suggested that Christie wanted to move from ‘this unpleasant place’, to use his words. His attempts to be rehoused led him to meet his local MP, George Rogers, Councillor Gough, and to visit the local headquarters of the Labour Party, all to no avail. This was because prospective buyers were turning up to view the place at odd times and he allegedly found this disconcerting as he had to show them round. He also said that his bad health should give him priority for rehousing. Finally he claimed that people were pointing the finger at him over the recent murders.5

The house changed hands. The owner, Mr G.W. Davies, wanted to sell it. At first, one Ernest McNeil, a former undertaker, was considering buying it and made several visits. He thought that Christie was ‘a weird bastard’ and Ethel was ‘very pathetic’. There was some discussion about the corpses in the wash house, but McNeil said that that did not perturb him. He asked ‘How on earth did those two bodies manage to stay in that wash house all that time without your dog smelling them?’ At this, Christie became ‘very annoyed’. However a survey of the property was not very positive and so McNeil declined to buy. Jack Hawkins bought it on 3 April and sub-let it to Charles Brown, aged thirty-five, a ‘man of colour’ and a boxer, who lived nearby at 26 Silchester Terrace. On 3 August 1950 he bought the house from Hawkins. Instead of there being two ‘flats’ on the upper floors, he rented the five rooms singly in order to maximise the return on his new investment (charging tenants £2 per week per room; the rent-protected Christie paid 12s 9d per week for his three rooms). In 1951 the new tenants were Beresford Brown (who was also black), Charles and Susan Edwards (who, by 1953, had a baby) and John Peterson. There were others, too: Ivan Williams, Franklin and Lena Stewart; all three from Jamaica. It was thus far more crowded than it had been.6

Christie explained what was happening and its effect: ‘When Mr Brown took over the house he put some odd bits of furniture which he brought into each room, the four upper rooms, and then let them to coloured people with white girls . . . It was very unpleasant because one or two were prostitutes’.7

At this time, the Christies began to put disinfectant down, both outside and inside the house. Christie later explained:

There used to be railings on the small area outside the bay window and those railings were taken away. Occasionally people used to bring their dogs down, and they used to prowl around, and there was nothing to stop it. There were frequent complaints in the whole of the street about that over a number of years, and very often other people in the street used to put down disinfectant in the area for that reason.8

Brown also wanted possession of half of the garden in order to store building materials and planned to dig up the garden to level it. Christie, with two skeletons buried there, was understandably opposed to this and consulted a solicitor, resulting in Brown backing down. Brown offered money, but again Christie turned him down. He claimed that to surrender the garden would have been to have surrendered all privacy (Nilsen also managed to monopolize a shared house’s garden for similar purposes).9

As to the situation inside the house, Christie said:

When the black man bought the house he installed some–they were rather disreputable people, the ones that had the white women living with them and they used to come down into the hall and spit. It used to happen often enough, and eventually we even had to remove the linoleum from the hall, which was my own, because of that, and we frequently put some ash or something down, and then some disinfectant, and my wife, when she was washing the hall, used to put disinfectant into the water. I used it more liberally; I used to just sprinkle it.10

Christie asked for help among officialdom towards the end of 1950, and the council’s sanitary inspector, Derek Kennedy, visited the premises. He stated:

Mr Christie complained, however, that a Mr Brown of 43 Silchester Terrace W10 had obtained possession of the rooms and could I endeavour to prevent these coloured people moving in. On several subsequent occasions, both Mr and Mrs Christie complained of the dirty habits of the coloured people.

Apparently Brown also bought 61 Blenheim Crescent and installed twelve black men there. Kennedy claimed Ethel ‘complained frequently of migraines and rheumatism’ and ‘she was of untidy appearance and held Mr Christie in high esteem’.11

Christie complained of the poor sanitary habits of his fellow tenants, whom, he alleged, used the communal toilet six to nine men at a time and then failed to flush it. This resulted in he and Ethel being forced to use public toilets instead. He also claimed that they were very noisy at all hours and made it impossible for Ethel to sleep at nights (white people in nearby Tavistock Road made similar remarks about their black neighbours), and summed it up thus, ‘our lives here have been and still are been made intolerable by the persecution of Brown and the coloured people who are certainly doing all possible to make it impossible for us’. He concluded, ‘We were persistently persecuted by the niggers’. Complaints to Brown were of no avail, ‘he encouraged it in an attempt to make us leave’.12

There were frequent quarrels. Christie claimed, ‘My wife has also been assaulted twice and threatened many times, as have I’. Two of the others were charged with assault at the West London Magistrates’ Court in 1951, resulting in a fine of £1 and a month’s probation. Mrs Edwards was one offender and apparently she and Mrs Christie argued over whether the front door be kept open or not on 16 April 1952. Mrs Edwards denied threatening Ethel. Christie and Brown argued over court costs in 1951, which Christie had deducted from the rent owed, and Brown allegedly threatened to assault him over this, ‘he keeps coming here creating a disturbance and threatening me’. Brown claimed, ‘I have not threatened him at all’. Christie claimed Brown was ‘a known bully and often in court’.13

Brown seems to have been a slum landlord of the Peter Rachman variety, who attempted to intimidate sitting tenants (whose rent was fixed) into moving in order to install higher-paying tenants, or more tenants by overcrowding. Brown later used the house as an illegal drinking club, so Christie’s complaints about his unscrupulous nature may be genuine in part. Christie’s sentiments about black people were shared by many poor white people in that locality in the 1950s, especially against slum landlords who appeared to be doing well for themselves in comparison to their own situations.14

Naturally, Brown put matters differently, complaining about Christie’s behaviour and saying that the coloured people caused no difficulties. In fact, the police often called, as Brown remembered: ‘Mr Christie, he always caused the trouble. Every time I went to get the rent he was always making a fuss over it’.15

Then there were health worries. Odess recalled he was ‘Very depressed, lachrymose, unfit to work, recommend holiday’ on 23 January 1950, but in 1951 his health was good. In July he was losing his memory and suffering from insomnia. Perhaps Christie’s worst year, health wise, was 1952. He was on his employer’s sick list for eight months of the year, up to early September. All these worries were taking their toll. Dr Dinshaw Petit, a psychiatrist, concluded, in 1952, that his symptoms were allegedly due ‘to rough and frightening behaviour on the part of some negroes who live upstairs, used it as a brothel and frequently get drunk and disorderly’. Petit thought that ‘his life was one of constant tension’ and he advised hospital. However, ‘he showed no evidence of insanity or irresponsibility’.16

Odess concluded that he was:

A nervous type and he had fits of crying, sobbing; he complained of insomnia, and headaches, and giddiness . . . he could not concentrate on his job. That is what I describe as a nervous breakdown. On 10th July 1950, in addition to these symptoms, he also complained that he had lost his memory–amnesia. He could not remember recent things. I prescribed rest; he had to stay away from his job. He was not fit, of course, and I gave him tablets for the night and medicine for the day–sedatives. He seemed to have recovered after a few weeks.17

Christie knew this too well, saying in 1952, ‘I have not been well for a long while, about 18 months. I have been suffering from fibrositis and enteritis. I had a breakdown in hospital’. As ever, he sought treatment. Odess referred him to others. Dr Charles Howell, a psychiatrist of St Charles’ Hospital, whom Christie visited in March, reported that Christie, who said he was anxious about the Evans murders, was ‘in a highly neurotic state and would have benefitted from the treatment offered but after a week’s daily he refused it’. Howell had suggested that Christie attend Springfield Hospital, but though he went in August, he never went again, as advised, apparently because ‘I would not go because my wife would have been left at home on her own with those black people there, and she was frightened to death of them because of the assaults she had had from them’. Howell also remembered, ‘he took pleasure in showing both to my registrar and myself press cuttings about a murder in which he claimed he was the star witness’. Odess last saw Christie professionally on 6 September 1952.18

Ethel also suffered ill health. Dr Odess first saw her in August 1948 and believed she was ‘also a nervous type’. Three times in May 1952 she was given medicine containing potassium bromide and phenol-barbitone. This was a sedative, to be taken in the day, and she also had sleeping tablets called soneryl. According to the doctor, ‘I should say she improved. The last time I attended her was 28th August 1952. She came to tell me that she had varicose veins, and I advised a form of treatment. She also had a skin eruption on her hands for which I prescribed some ointment’. She may also have had rheumatism.19

Although we know more about Christie’s final years, his neighbours knew very little about him. A local newspaper offered the following verdict on the man and his innocent pastimes:

This quiet spoken trilby hatted person, was known to have been obsessed by a sole hobby, photography. He was a keen amateur photographer and delighted in taking pictures of the local festivities in north Kensington. Last summer when this newspaper and its staff went on its annual outing, it was Mr Christie who loaned a member of staff his German made camera. ‘He was not a very friendly man’ is the comment made by this staff member. ‘He was quiet and kept himself to himself, but a friend of mine said he would be willing to lend me a camera for the trip’.

Despite his keen interest in photography, Christie was not expert with the camera: reproductions of his prints were full of dark shadows or were in a dull brown. In any case, he pawned his camera on 9 August 1952 in Battersea. ‘Neighbours say that he had stated that he was particularly looking forward to the street celebrations for the Coronation, and had planned to take several pictures then’; in 1945 he had photographed street parties on VE Day. Neighbours took their film to be developed by him. Finally, ‘he was not a good mixer, and seemed to spend most of his time with his dog and his all consuming photographic hobby’. Franklin Stewart, a fellow tenant recalled, ‘I never had anything to do with them except to say “good morning” or “good night.” ’ Another neighbour said that he was, ‘a very polite man who never talks to anyone very much’. ‘His wife, a Mrs Ethel Christie, was also of a very reticent character.’ Christie was also a QPR fan, talking about attending their home matches and having a badge in his possession. According to a neighbour, William Swan, he was the acme of humdrum respectability, noting, ‘He would go off to work, neatly dressed, carrying a rolled up umbrella’. Another saw a different side to him, ‘He always looked as if he had just stepped from a cold shower –shivering and weak’. He was also noted as someone who went for solitary walks at nights, and drank alone. Yet to his neighbours and shopkeepers he was polite, ‘Gentleman Johnnie’, and always raised his hat in the street.20

Christie claimed he rarely drank, stating ‘I seldom touch the stuff . . . perhaps Christmas and an occasional glass of beer about three times a year’. He recalled visiting neighbours with his wife at Christmas 1951 and having a drink of port. After trades union meetings he went for a cup of tea with his fellows.21

Odess was sympathetic towards Christie, and in a letter to Dr Howell wrote, ‘I am inclined to agree with you about his anxiety state. There is no doubt a functional element present. At the same time, I wish to point out that he is a very decent, quiet living man, hard working and very conscientious. He is anxious to return to his work as soon as possible’. He also thought he was kind towards his wife.22

Although the couple seemed to have few friends or visitors (Christie never saw any of his relations after leaving Halifax in 1923, and had no contact with them–except for sending his mother a photograph of himself in police uniform–and never spoke of them), those who knew them seemed to like him. John Clark, of number 13, recalled, ‘I have had conversations with both of them and they have been to my flat. They always seemed a nice friendly couple and I never heard of any quarrel’. Pamela Newman, aged thirteen, of the same address, reported, ‘he used to talk to me about flowers and cats’ and she visited the Christies on occasion. Apparently Christie once sat up for two nights, looking after her sick cat, and told her how to box up plants. He even took an eight-year-old to the Royalty Cinema, Ladbroke Grove. William Swan of number 9 recalled, ‘I have seen both of them fairly regularly. I used to see Mr Christie in the garden and we would talk and his wife, Ethel, used to come in sometimes to ours and have a cup of tea with my wife’. Lena Brown, a fellow tenant, claimed, ‘I did not know the Christies very well. I used to speak to them sometimes. I never heard them quarrelling’. Ethel corresponded irregularly with her brother, but he recalled that when he saw her in June 1952 she ‘appeared quite happy except for black concerns . . . Ethel has never complained to me about the conduct of her husband but she was not the type of person who would complain in any case’. Christie himself said, ‘We didn’t make many friends. We were devoted to one another and always went about together’. He never appeared in group photographs of neighbours. A neighbour noted, ‘He was always regarded as a family man whose only interests outside his work was his home’. He was a loner by nature and his hobbies were solitary ones. This could have been the result of a lack of social confidence. He never answered the door except to those few callers who were expected.23

Others also spoke of his good nature. Bessie Styles of number 11 later said, ‘It’s just not true that he was a grumpy man. He just kept himself to himself’. Christie was kind to local children, though only on his terms. He would make them paper kites and took photographs of them at parties. The pictures were badly developed and on cheap paper, but he gave them out: ‘There, take this into mummy–that’s you’. But on the other hand, he opened the windows if he heard children playing football or cricket in the street and told them to clear off. Councillor Gough related, ‘He was a normal kind of man as far as I could see. I talked to him a lot. He could be very happy go lucky and congenial when he wanted to be. Also he had a sense of humour. He used to pull my leg saying he was a Tory. Afterwards he admitted he voted Labour’. Christie said, ‘I’ll join [the Labour Party] if you get me a flat’. A less sympathetic side to his character was shown when he attended a residents’ meeting on September 1952 about funding a children’s Coronation party, where he was the only one who refused to contribute three pence, saying ‘I’ll have to consult my wife’.24

Relations between the Christies are often reported as seemingly good. Rosina Swan, of number 9, said they were ‘very happy’. Sidney Denyer, an insurance agent, recalled, ‘I formed the opinion from the various conversations I had with Mr and Mrs Christie that they were an exceedingly devoted couple’. Louisa Gregg of number 9, whom Ethel often visited on weekdays to watch TV there, said, ‘she did not talk about her personal affairs to us . . . she has never mentioned any quarrel with her husband’. Christie, unlike many husbands at this time, shared the shopping duties and bought a loaf every day from, ironically, Lancaster Food Products.25

Rosina recalled, ‘She usually came in on a Thursday for an hour to see the children’s television in my home’. Doubtless it provided Ethel with a break from her other woes at number 10.26

Yet there is a less rosy view of the Christies’ marriage provided by a fellow tenant, one Joan Howard. She recalled, in 1953, that Christie had photographs of Beryl and Geraldine Evans, as well as newspaper cuttings about the murder case, and Ethel showed these to her, but as Christie returned, ‘he had told his wife to put them away as he had had and seen enough of it’. On another occasion, ‘she said her husband was mean to her and cruel to her but she didn’t know why she stayed with him. She did not explain what her husband did to her. She said that her husband treated her badly since he had been in court in connection with the murder . . . I thought she was saying it in spite’. Apparently, ‘His wife did tell me that he was not sexy’.27

Joan and Christie did not get on and, according to her, she saw his sinister side. He asked her if he could take pictures of her in the nude, but she declined. At the time the suggestion was made, Ethel was, bizarrely, with her husband. Later the thwarted Christie called Joan a prostitute who took men to her room, which she denied. Apparently she threatened Ethel and Christie said to her, ‘the only place for women like you, is dead. If I had my way, I would do it’. According to Joan, ‘He was very excited at the time’. A constable arrived, as did Charles Brown and his ‘wife’ (actually one Marjorie Evans, with whom he lived). Later Christie said to her, ‘Remember what I said, I’ll still do you in’. She recalled that when she arrived home late, ‘Christie used to peer around the door and as I went up the stairs he used to come out and shine a torch on me’. She recalled that Christie spent a lot of time in making a rockery in the garden. In 1953 there was an interview with a ‘Pat Howard’, who was the same woman, in a newspaper. She came out with a more dramatic story, with Ethel confiding in her thus, ‘I am convinced that my husband had something to do with those two murders’, but added ‘I couldn’t leave him now. I have lived with him too long for that. Whatever he has done, I am still in love with him’. It is uncertain whether this statement is true or not, and if it is, just what did Ethel know? The statement, however, was made with the benefit of hindsight.28

Sexual relations ceased, too. Christie recalled ‘Just fell away–just didn’t bother’. He also said, ‘We never spoke of cessation, it just happened’. But it ‘made no difference to our affection for each other’. Yet this is not unusual among middle-aged couples, especially for those whose sex drives have never been strong.29

Yet Christie’s desires and his latent homicidal urges were surfacing again. He needed gratification and so began to hunt for new victims. Thus he became a frequenter of cafes in search of women. He was a regular at Peter’s Snack Bar on Goldhawk Road, where he met Elsie Morris, who came to visit him and Ethel once. In early 1952 he was often seen there with an eighteen-year-old woman from Wimpey’s snack bar further down the road. This continued for about six weeks, three or four times a week. In November 1952 he often went to the Seven Stars snack bar, also on Goldhawk Road, as his colleagues also did, and he was often seen with one Rita, another eighteen-year-old; Lilian Campbell, aged twenty, an art student; and one Kay, aged seventeen. He asked about them, paid for their drinks and they talked to him and allowed him to photograph them. At the same time, one Elsie Barltrop met him in a tea shop in Marble Arch and said he showed her photographs, purportedly of his two daughters (the aforementioned Kay and Rita), though he introduced himself as John Halliday of Argyle Street, King’s Cross.30

Christie even invited one of these girls back to his rooms when his wife was present. This occurred on 5 November, in either 1951 or 1952, ostensibly to watch the fireworks. A neighbour recalled, ‘Mrs Christie also told my wife that the same girl had come to their house one Sunday and Mr Christie had tried to get her, Mrs Christie, to go and cook the dinner, and leave him alone with the girl. She told my wife she would not go and they had some words over it’. Ethel’s presence in the house was a bar to what Christie wanted to do, and her days were numbered.31

It was on 4 July 1952 that Christie again tried to move house. He wrote to the LCC, complaining that his ill health–‘I am registered as a disabled person owing to a damaged right shoulder and nervous disability’–meant that he had to be urgently rehoused. He stated that their present rooms were ‘very damp in places’. A sanitary inspector was summoned, but no repairs were carried out. The Christies also discussed whether Ethel’s brother could house them in one of his properties in Sheffield, but he said he could not.32

Yet Christie’s health improved, for he returned to work in the autumn of 1952. He was now assigned to the Cressy Road Depot, Hampstead, and went to work by Tube. Here he was one of thirty-four invoice clerks under the supervision of George Leathley Burrow, Group Accountant, who found Christie ‘quite satisfactorily as far as his work was concerned, but he had been a trades union official and he was the type of man who, if there was any dispute regarding working conditions, liked to be involved’. Christie earned about £7–8 per week and claimed he had an independent income, but ‘was always taking tablets which he said kept him going’. For once he enjoyed a clean bill of health throughout this period and worked properly. He seems to have enjoyed his time there and said that he liked his boss very much. But he continued his old stories. Eileen Drew recalled his telling her that he had studied to become a doctor and that his father was a famous Edinburgh surgeon, upon whose death Christie abandoned his medical ambitions. Yet Christie was not popular, as James Morley recalled, ‘He had no friends in the firm’ . Alfred Gattrell said ‘he always kept himself to himself’ and recalled Christie was always smartly dressed. Christie was responsible for First Aid and said of himself, ‘the men had great faith in me and their injuries always got better quickly’. At lunchtimes he went to Joseph Cattini’s cafeéé on Constantine Road, where he often met a married woman.33

Christie left this job on 6 December 1952, allegedly because of ill-health (due to, in his words, ‘an incident at work regarding a half caste Indian woman’), though he did not see Odess about this. Burrow recalled, ‘He left at his own request, having given proper notice. He said he had obtained a better job, which I understood to be in Sheffield’. A colleague, Horace Maser, said that Christie maintained he left for a job with an engineering firm in Sheffield. However, the real reason for leaving his job was a sinister one.34

Charlotte Barton, who worked at the receiving depot at 138 Walmer Road, Kensington, was one of the last people to see Ethel Christie alive. She stated, ‘Mrs Christie was a customer and brought her laundry to the depot every fortnight, usually either on a Thursday or a Friday. The last time she called was Friday 12th December, when she left some washing to be done. It was never called for and I have never seen Mrs Christie since’. Mrs Jennie Grimes, a neighbour, remembered last seeing Ethel three weeks before Christmas. Lena Stewart said, ‘The last time I saw Mrs Christie was about ten days before the baby was born [18 December]’. James Stewart, another resident of number 10, recalled, ‘The last time I saw Mrs Christie was shortly before Christmas. She seemed alright then’. Dr Odess also asked after her, ‘he said she had gone away to stay with her sister–in the Midlands, I think.’35

Ethel seems to have had no idea about her fate. On 10 October she wrote to her brother, who had visited her in June, telling him that the landlord refused to repair the cracks in the front room, ‘so Reg has done it, quite good, too’. She also wrote, ‘if we could only get somewhere else to live it would be better for us’. She wrote another letter to her sister on 10 December, but it was never posted.36

Perhaps the worst of Christie’s murders was of the woman he claimed he loved, as far as that word had any meaning for him. According to Christie, Ethel was suffering from increased mental strain. He stated:

My wife had been suffering a great deal from persecution and assaults from the black people in the house, No. 10 Rillington Place, and had to undergo treatment at the doctor’s for her nerves. In December, she was becoming very frightened from these blacks and was afraid to go about the house when they were about, and she got very depressed.

On December 14 I was awakened at about 8.15am. I think it was my wife moving about in bed. I sat up and saw she appeared to be convulsive. Her face was blue and she was choking. I did what I could to try and restore breathing, but it was hopeless. It appeared too late to call for assistance, that is when I could not bear to see her so. I got a stocking and tied it around her neck to put her to sleep.

Then I got out of bed and saw a small bottle and a cup half full of water on a small table near the bed. I noticed that the bottle contained two pheno-barbitone tablets and it originally contained 25. I then knew she must have taken the remainder. I got them from the hospital because I couldn’t sleep. I left her in bed for two or three days and didn’t know what to do. Then I remembered some loose floorboards in the front room. I had to move a table and some chairs to roll the lino back about half way.

Those boards had been up previously because of the drainage system. There were several of these depressions in these floorboards. Then I believe I went back and put her in a blanket or sheet or something and tried to carry her. But she was too heavy and so I had to sort of half-carry her and half drag her and put her in that depression and cover her up with earth. I thought that was the best way to lay her to rest. I then put the boards and lino back. I was in a state and didn’t know what to do, and after Christmas I sold all my furniture.

Christie later said, ‘I did not want to be separated from her. That is why I put her there. She was still in the house’.

In at least two aspects, this account is incorrect. Camps later found no trace of barbiturate in Ethel’s body. Also, the murder was almost certainly premeditated, as Christie withheld his wife’s letter to his sister-in-law, which was written by her on 10 December, but altered the date to one five days later before posting it. However, there seems little doubt that Christie strangled his wife on about 14 December 1952.37

Christie asserted throughout that this was a mercy killing and later said, ‘I loved my wife. I hated seeing her suffer. I decided to end her pain forever. My wife died peaceably and with practically no pain’. His words show that he justified the murder to himself by the use of euphemism, ‘I put her to sleep’. However, unlike four of his other victims, he did not render her unconscious with gas prior to strangulation: she knew she was being killed. His motive was almost certainly his desire to kill again. Having killed already with impunity, he had the serial killer’s addiction to murder and could not resist this aspect of his nature. Christie later said, ‘After she had gone, the way was clear for me to fulfil my destiny’.38

On the following day, Christie added to the letter written by his wife to her sister, ‘We have no envelopes so I posted this for her from work’ and dated it 15 December. Henry Waddington, a local government clerk of Sheffield, recalled seeing it and said it was not in his sister’s handwriting. Christie later wrote the following message in a Christmas card:

Dear Lil,

Ethel has got me to write her cards for her as her rheumatism in her fingers is not so good just now. Doctor says its the weather and she will be O.K. in 2 or 3 days. I am rubbing them for her and it makes them easier. We are in good health now and as soon as Ethel can write (perhaps by Saturday) she is going to send a letter. Hope you like the present. She selected it for you. Reg.

At the top, he wrote, ‘DON’T WORRY. SHE IS OK. I SHALL COOK XMAS DINNER. Reg’.39

Christie had to account to his neighbours for Ethel’s absence. Rosina Swan spoke to him on 19 December. ‘He said he had got a job in the north–a transfer–and that his wife had gone on ahead to prepare. He said the place was Sheffield’. Later that day the two had another chat. Mrs Swan stated, ‘He spoke to me in the garden, there is a short wall between the two gardens. He had a piece of paper in his hand, and I think he said it was a telegram from his wife. He said she had arrived safely and “love to Rosie” ’. Christie added, ironically, ‘I will have to choke her off for sending love to her and not to me’. To Jennie Grimes, he said, just after Christmas, ‘she had gone to see her sister, who was having a woman’s operation. He said she had gone north, to Birmingham’. Eileen Styles, another neighbour, was told likewise, albeit to visit her sister, ‘he said he had not told anyone else as he didn’t want it to get around’. To Hookway, he said, ‘he was going to Northampton to look for a job up there as he was out of work. I understood him to say that his wife was with her sister in Northampton, and that he was joining her there’. James Stewart reported, ‘In February I spoke to Mr Christie and asked him if Mrs Christie was sick, as I was not seeing her. He said that she was not sick, but that she had gone to see her sister who had a shop and who was sick. He did not tell me where the sister was, but somewhere in the country. He said he was expecting her the following week’. Christie also told his butcher that his wife would be coming home soon, which he looked forward to as he was fed up with shopping for food.40

Rosina saw Christie again. She said that this was ‘Several times whilst I was shopping. I asked him on one occasion how his wife was and he said she was looking rather pale, as they had had a lot of flu in the north, and he was probably going up on the following Sunday to see her on an excursion’.41

On Christmas Day itself, John Gregg of number 9 invited Christie over in the evening. They exchanged presents and watched television. He explained that his wife was away for a few days.42

Life for Christie was increasingly wretched and squalid, as he described the situation:

I made a bed on some bedding on the floor in the back room. I had about four blankets there. I kept my kitchen table, two chairs, some crockery, and some cutlery. These were just enough for my immediate needs because I was going away. I wasn’t working and had a meagre existence. I was getting money from the employment exchange. This was £2 14s.

He certainly needed money badly. On 17 December, he sold his wife’s wedding ring and her gold wristwatch for £2 10s at Barnet Pressman’s jewellery shop on 166 Uxbridge Road, Shepherd’s Bush, stating ‘I took it off her finger as a keepsake, but sold it . . . when I was hard up and hadn’t enough money to get food’. He sold a three-piece suite, two sideboards, linoleum, three chairs, a bed and a chest of drawers. This transaction, between Christie and Hookway, took place on 8 January 1953. Christie had hoped for £15, but had to admit ‘I got £11 [actually £12] for the furniture and £2 for some other bits that I sold’. Hookway left a mattress ‘because it was in a rather disreputable state’. Edward Allen of Walter Hildreth Ltd removed the furniture. The great tragedy for the historian is that though the drawers were stuffed full of photographs, papers, diaries and police note books, these were all destroyed by Hookway, though not before he saw there were some letters addressed to Christie from one Edith Hunt, whoever she was. Christie offered to assist Hookway ‘in a case between myself and a hire purchase company’, but Hookway refused his help. Christie also stopped paying his rent on 5 January, which points to the fact that he thought that his time at 10 Rillington Place was limited. Brown recalled collecting money in December and that on 5 January that Christie put a notice on his door informing him that he could have his cash, but when he arrived for it Christie was not at home. Or perhaps he no longer cared and was succumbing to a sub-conscious self-destructive impulse.43

Christie needed more money, however. Remembering that his wife had an account with the Yorkshire Penny Bank, Sheffield, which she had opened on 14 July 1944, he decided to use his new-found skill of forging handwriting. Frederick Snow, the manager of the Haymarket branch, had no doubts. On 27 January he received a letter written on the previous day, allegedly from Ethel Christie of 10 Rillington Place. It ran, ‘I wish to close my account. Please forward to me any amount due. Enclosed is my bank book’. Snow recalled, ‘I compared the signature on the letter with the specimen signature dated 14th July 1944, and they agreed. I had no reason whatever to believe that signature was otherwise than genuine. We forwarded the balance of that account, £10 15s 2d, by registered post’. An acknowledgement was received shortly afterwards and again it seemed to be in order. On 27 February Christie sold some of his wife’s clothing for £3 5s. He also received a cheque for £8 on 7 March from the Bradford Clothing and Supply Co. From 22 January to 18 March he also received a weekly £3 12s in state benefits.44

Lily enquired after her sister on 17 January, imploring her to ‘Write soon, we get awfully anxious about you in that place. I wish Reg could find another place’. The letter was never answered, but nor was it destroyed. She later recalled, ‘I did not hear anything further, I became very worried and about a month ago I wrote to my sister . . . I wanted her to come to Sheffield, because I know they were having some trouble with coloured people’. But she took her concerns no further, and so Christie was granted further respite to continue his evil work.45

Yet some of Christie’s behaviour did attract attention. Lena Stewart returned from hospital at the end of December, after having given birth to her child (Beresford Brown, whom she married in 1953, was the father). In January:

I noticed that he was disinfecting the place. He was sprinkling disinfectant all over the passage that leads from the front door. I think it was Jeyes. It was strong . . . He disinfected the back yard. I saw him pouring it down the drains. I also saw him put it outside under the window of his front room where I used to put my pram. He told me one morning that somebody had thrown dirty water down the drain. He never spoke to me as to why he disinfected the front passage or outside the front room window. He generally did the disinfecting between 8.30 and 9 am when everybody had left the house to go to work.

James Stewart thought that the disinfectant was being laid down as early as October, though he thought this could have been because dirty water was being thrown down by some of the other tenants. He did not think Christie’s actions were odd. 46

Christie had killed again, and was about to enter an even more destructive phase of his murderous career. As before, no one had suspected that a murder had occurred, and thus, undetected, he may have felt invulnerable, and now he had a freer rein. However, he had also unwittingly lit a fuse under himself, for he had now concealed a corpse where he lived, which would smell and would eventually be found. But, as ever, Christie thought only of the short term and disregarded what his intelligence must have known was the beginning of the end.

Ernest John Christie. (Jack Delves’ collection)

Mary Hannah Christie, neéée Halliday, 1917. (Jack Delves’ collection)

Ethel (wife of Percy), Percy and Mary Christie. (Jack Delves’ collection)

Black Boy House, 2010.

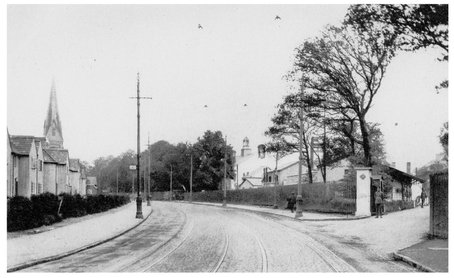

5. All Souls’ Church, Halifax, c.1900. (Author’s collection)

Halifax Post Office, c.1920. (Author’s collection)

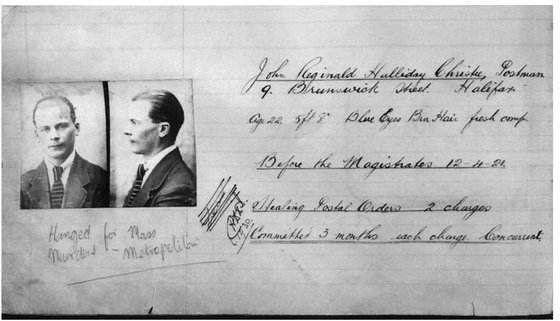

John Christie, 1921. (Wakefield Archives)

RAF Uxbridge. (Ken Pearce’s collection)

Empire Cinema, Uxbridge. (Ken Pearce’s collection)

Hillingdon School, 1930s. (Ken Pearce’s collection)

Southall Park, 1920s. (Ken Pearce’s collection)

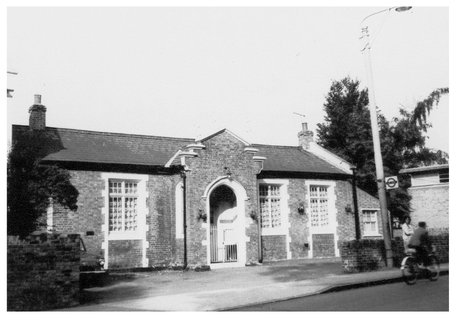

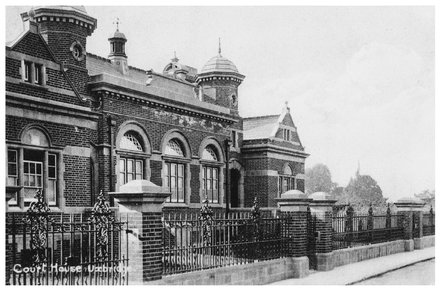

Uxbridge Magistrates’ Court. (Ken Pearce’s collection)

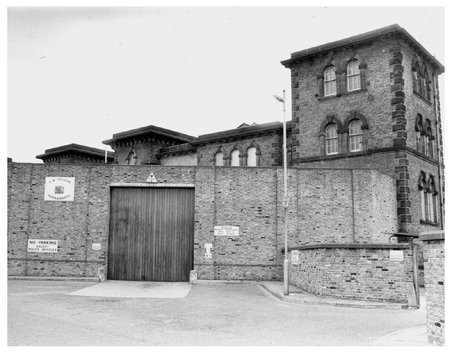

Wandsworth Prison, 1980s. (Author’s collection)

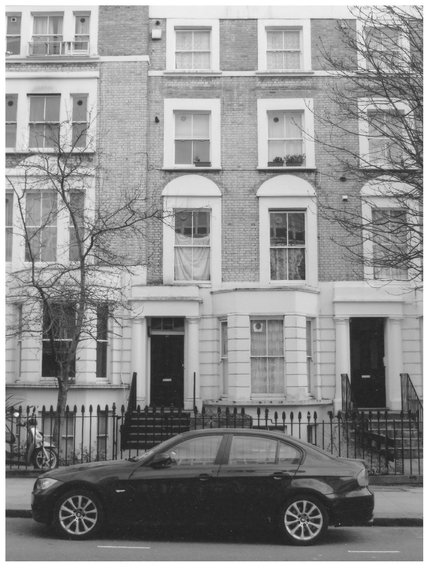

No. 23 Oxford Gardens, Notting Hill. (Author’s collection, 2010)

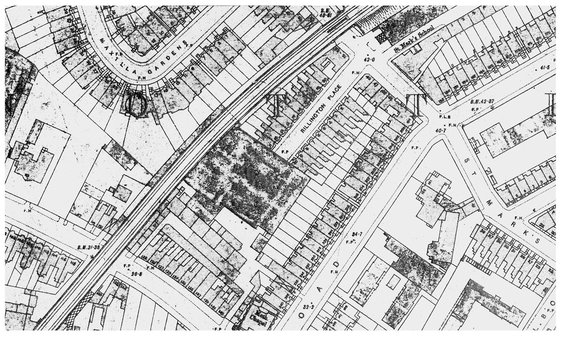

Map of Notting Hill, 1914. (Kensington Library)

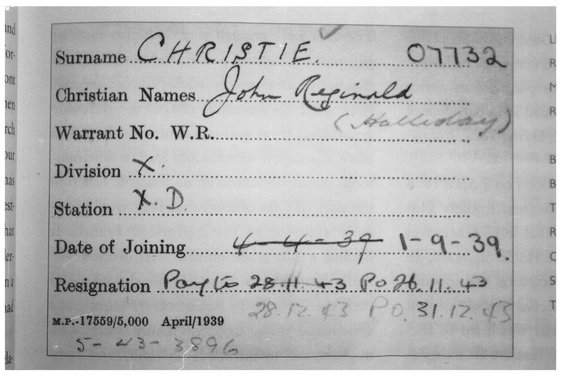

Christie’s police record, 1939–1943. (Scotland Yard)

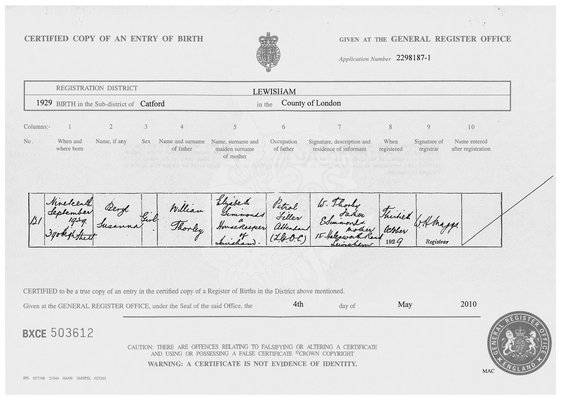

Beryl Evans’s birth certificate. (Author’s collection)

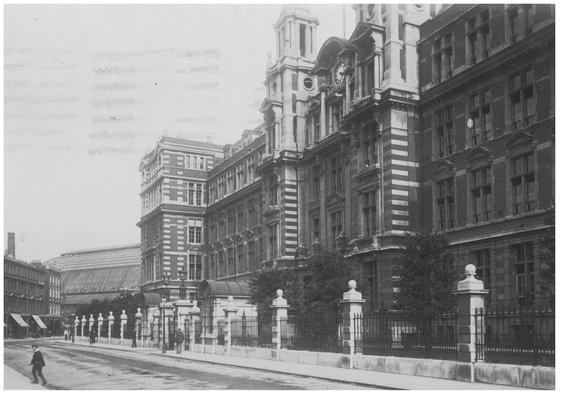

GPO Savings Bank, Blythe Road. (Author’s collection)

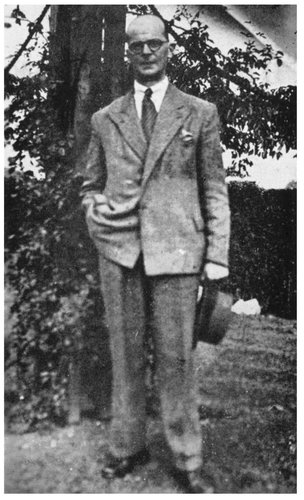

John Christie, c.1950. (R. Maxwell, The Christie Case)

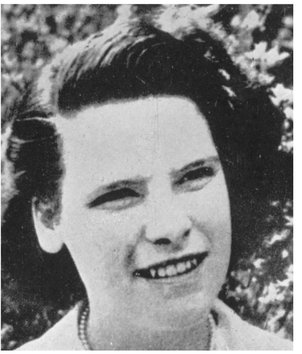

Kathleen Maloney. (R. Maxwell, The Christie Case)

Maureen Briggs. (R. Maxwell, The Christie Case)

Hectorina MacLennan. (R. Maxwell, The Christie Case)

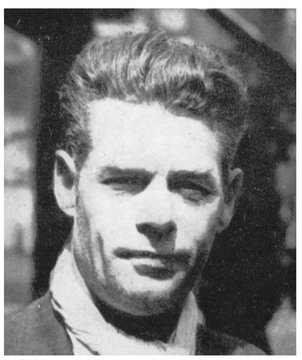

Alexander Pomeroy Baker. (R. Maxwell, The Christie Case)

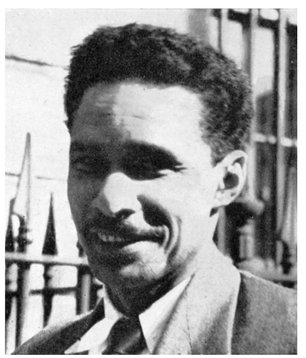

Mr Beresford Brown. (R. Maxwell, The Christie Case)

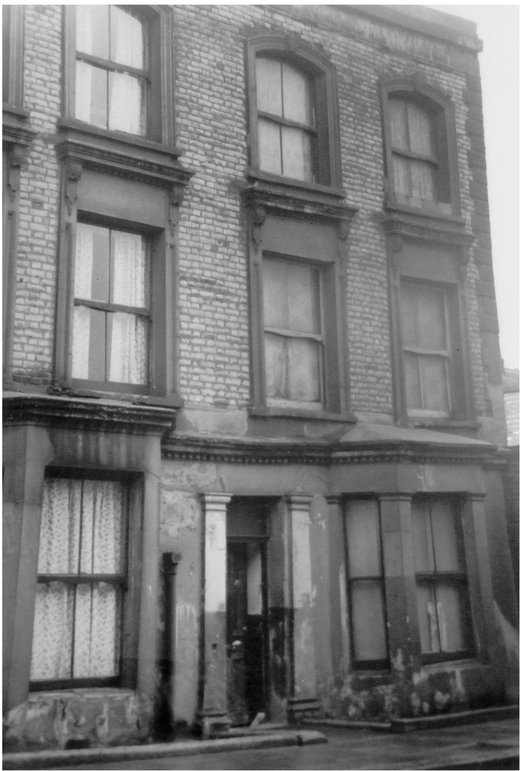

Rillington Place, 1953. (National Archives)

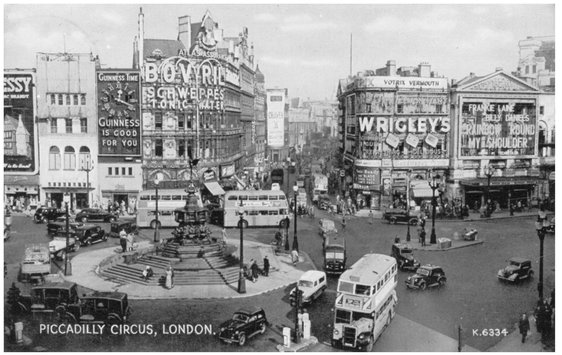

Piccadilly Circus, 1953. (Author’s collection)

Furniture being removed from the murder house. (R. Maxwell, The Christie Case)

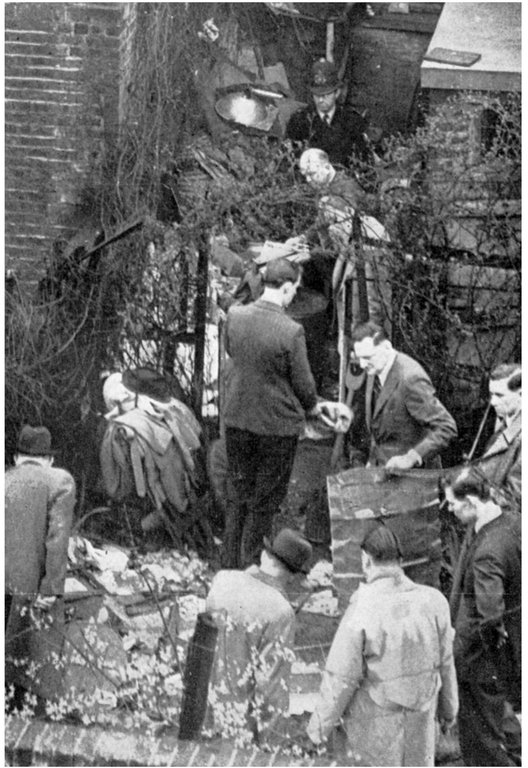

Search of the back garden. (R. Maxwell, The Christie Case)

Removal of a corpse from the murder house. (R. Maxwell, The Christie Case)

Putney Bridge, 2009. (Author’s collection)

Old Bailey.

(Author’s collection)

Pentonville Prison, 2010. (Author’s collection)

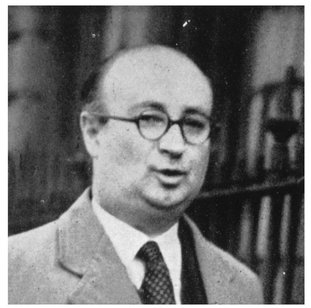

Derek Curtis-Bennett. (R. Maxwell, The Christie Case)

West London Magistrates’ Court, 2010. (Author’s collection)

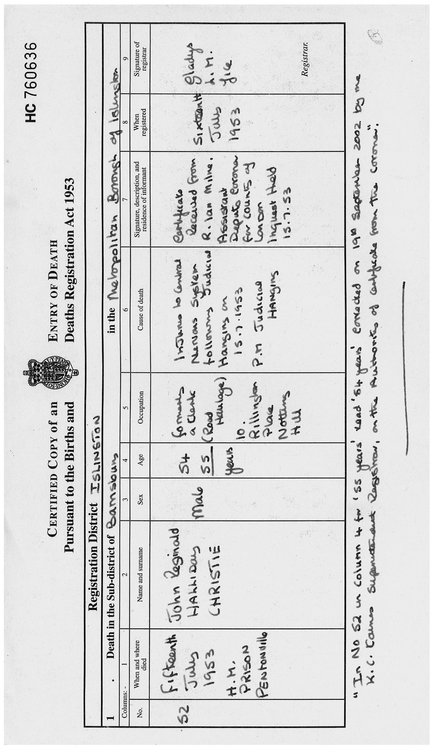

Christie’s death certificate. (General Registry Office)

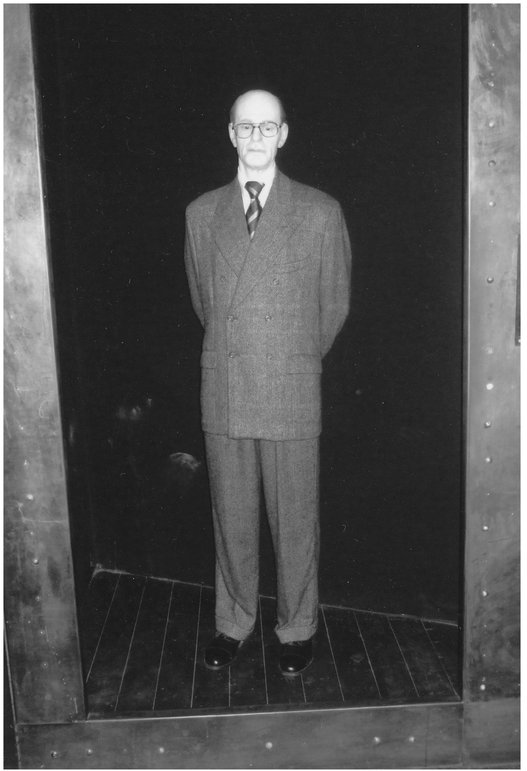

Waxwork of Christie at Madame Tussaud’s, 2011. (Author’s collection)